by John E. Dolan

Unlike most inventors Alfred Nobel combined technical creativity with commercial flair, both to a very high degree. A lack of capital proved no hindrance to Nobel and having borrowed it he had, within ten years, founded an international group of dynamite companies in Sweden, Finland, Germany and Norway before turning his attention to the United States, Great Britain and the rest of Europe.

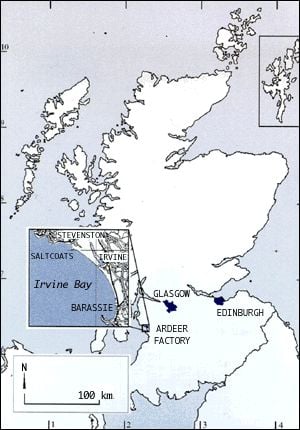

Outline map of Scotland showing location of Ardeer.

Although potentially very lucrative Nobel found Great Britain one of the most difficult of all his ventures mainly for bureaucratic reasons.

Nitroglycerine as a blasting explosive was first advertised in the U.K. in 1865. The first recorded demonstration was in Cornwall in 1865 at the exhibition held by The Royal Cornwall Polytechnic Society. The first practical trial with the liquid was carried out at West Hoe Quarry in April 1866. It was also in use in North Wales in the Glyn Rhowy Slate quarry at Llanberis later in the same year.

Nobel took out a British patent for dynamite in May 1867. He came over to England a third time and began a vigorous public relations exercise to convince the authorities and potential users of the safety of his new explosive. The first demonstration was carried out at Merstham Quarry, Surrey in the south of England in July of 1867. During this demonstration Nobel set fire to sticks of dynamite, threw packets of the explosives from a cliff, and detonated it in various ways to demonstrate both what it could do and its safety. The demonstrations, however, failed to persuade the authorities at this time.

At this time the law relating to explosives in the United Kingdom was governed by the Gunpowder Act of 1860 which pre-dated Nobel’s use of nitroglycerine (blasting oil) and the terms of the Act were, therefore, technically completely out of line with the new explosive. In 1866 Parliament attempted to deal with inadequacies by passing the Carriage and Deposit of Dangerous Goods Act. This Act failed to provide any means of enforcement and, through lack of understanding, failed completely to address the real problem of safety and sensitivity. The authorities cautious approach was unfortunately re-enforced in the U.K. by an explosion of a consignment of liquid nitroglycerine which came in through Liverpool and blew up at Caernarvon (9th July 1869) and the Government of the day passed an act totally prohibiting the manufacture, transport or sale of nitroglycerine or any product containing it in the U.K. (Explosives Act of 1869).

Nobel, however was not to be deterred. He persisted and after two very frustrating years was able to persuade the authorities of the efficacy and safety of dynamite as distinct from liquid nitroglycerine and got an easing of the strict regulations but was still unable to obtain permission to establish his business in England. Eventually he turned to Scotland where he found a receptive group of entrepreneurial businessmen with whose help, and principally assisted by John Downie, then the General Manager of the Glasgow shipbuilding firm the Fairfield Engineering and Shipbuilding Company, Nobel set up a company with a factory site on the west coast of Scotland some 30 kilometres south of Glasgow on the Clyde Estuary at Ardeer in April 1871 with the rights to work his patents under the name of The British Dynamite Company. John Downie was appointed the first General Manager and Secretary, a post which he held until his untimely death in a tragic accident when destroying some defective dynamite in Southern Ireland.

|

|

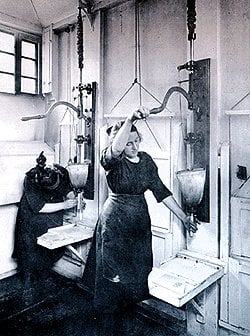

Nitroglycerine nitration – the first Hill in 1875. |

The factory was designed by P.A. (Alarik) Liedbeck, Nobel’s friend and the engineer who had assisted him with the Heleneborg plant and who was the manager of his first factory at Vinterviken in Sweden. The factory at Ardeer therefore benefited substantially from the experience already acquired from Nobel’s earlier factories. The equipment installed was a considerable improvement on the early systems. From the very start nitroglycerine was produced on the batch process plant which, with its “one-legged stool” (to prevent the operator falling asleep) is now almost a logotype for dynamite manufacture. The first 336 kilo charge of nitroglycerine was produced at Ardeer on the 13th January 1873.

The first batch of dynamite was produced later that year by hand mixing the kieselguhr and nitroglycerine in brass-lined wooden boxes in 45 kilo lots. The cartridging had the benefit of the already developed dynamite cartridging machine. All these process houses had sand floors which had full Government approval on the somewhat dubious grounds that the Ardeer sand was of “such a fine quality that it did not constitute ‘grit’ within the meaning of the Explosives Act of 1875“. Another peculiar “safety” precaution was that the girls who operated both these processes worked in their bare feet.

Dynamite cartridging, Ardeer, in the 1880s.

The kieselguhr with which nitroglycerine was mixed to produce dynamite was found in substantial deposits in Scotland at Loch Cuithir on the Isle of Skye and in Aberdeenshire. The supply of acid for the nitration process was at first obtained from The Westquarter Chemical Company near Falkirk, half way between Edinburgh and Glasgow and conveniently on the banks of the Grand Union Canal at Laurieston. Nobel bought into this company and entered into partnership with its director, Mr. McRoberts who, in 1874, became his chief chemist and, eventually, Ardeer’s factory manager. McRoberts’ name has become synonymous with the design of early gelatine mixing and cartridging machinery some of which is still in use today.

In 1877 the company name was changed to Nobel’s Explosives company.

It was to the Westquarter factory that Nobel turned when he determined to manufacture detonators in Scotland in 1876. When manufacture began in that year only six workers were employed using mercury fulminate brought in from abroad. However, in 1878, Nobel decided to produce the fulminate requirement on site and a small factory for this purpose was built at Redding-Moor about half a kilometre south of the Westquarter factory and on the other side of the Grand Union Canal. As soon as the decision to build this factory had been taken Nobel sent to Sweden for another young assistant, C.O. Lundholm to take charge of the technical production. Lundholm completed the job in twelve months and then, in 1879, went to Ardeer as assistant manager where he became a household word. From these small beginnings the Westquarter factory grew until, at its peak, 1,700 people were employed producing some 73 million detonators.

It was about this time that McRoberts moved to Ardeer and sold his house “Hawthorn Cottage” in Laurieston to Nobel to serve as his residence when in Scotland. “Hawthorn Cottage” is still standing and occupied today and is, in fact the only building directly associated with Alfred Nobel remaining in Scotland.

|

|

‘Hawthorn Cottage’ – Nobel’s house in Lauriston. |

The company prospered during the latter part of the 1880’s developing an impressive overseas trade and, had by the time of Nobel’s death become the largest exporter of explosives in the world. This had been achieved through diversification into and the development of new products, including blasting gelatine in 1879, gelignite in 1881, ballistite in 1887, guncotton in 1892 and cordite in 1895.

The export trade was greatly facilitated by the access to the sea which was fully exploited by loading from the beach (a process in which it was “all hands to the pumps”, even the factory girls assisting) into the sailing vessel “The Jeannie” (named after the wife of Mr. McRoberts, Nobel’s Factory Manager).

Later, the acquisition of the harbour facilities at Irvine provided quayside loading for coasters and, over the years, a succession of explosives steamers was acquired or built and owned to serve the overseas trade, each, with one famous exception, named after the wives of company dignitaries:

The Alfred Nobel

The Lady Gertrude Cochran

The Lady Tennant

The Lady Anstruther

The Lady Dorothy

The Lady McGowan

The Lady Helen.

Interestingly enough Nobel protested about the naming of the “Alfred Nobel” pointing out that a ship was a “She” and not a “He”, adding the comment that “she is in any case much too elegant to be named after an old wreck like me.“

At its foundation in 1871, the British Dynamite Company began with a plot of only 400,000 square metres, but expansion was rapid, and by 1907, Nobel’s Ardeer factory was reputed to be the largest explosives factory in the world.

The Ardeer site proved to be ideally suited to the manufacture of high explosives. When Alfred Nobel moved to the area in 1871, he described it vividly in a letter to his brother.

“Picture to yourself everlasting bleak sand dunes with no buildings. Only rabbits find a little nourishment here; they eat a substance which quite unjustifiably goes by the name of grass. It is a sand desert where the wind always blows often howls filling the ears with sand. Between us and America, there is nothing but water a sea whose mighty waves are always raging and foaming. Now you will have some idea of the place where I am living. Without work the place would be intolerable.”

In reality, Ardeer was the perfect location for Nobel’s factory. Apart from being an easily accessible location for shipping, and being conveniently close to the thriving industrial heart of central Scotland, it was relatively isolated, being situated on a natural peninsula with the Firth of Clyde on its west side, the River Garnock to the east, and the mouth of the River Irvine to the south. Perhaps more important still was the suitability of the land itself, the sandy surface providing a perfect material for the raising of embankments and mounds to protect the danger zones within the factory, which themselves could be separated by wide safety distances.

The new factory, as Nobel’s colourful description implies, was very remote, a very favourable point in the eyes of the nervous public, but its isolation meant that there were no roads only a dirt track through the sand dunes. Equally there were no services and, from the very outset, the factory had to be self-sufficient. Steam was no problem as a single boiler house was soon built at the factory entrance. The water supply did, however, cause problems. Factory water was pumped from a nearby coal mine, the Lucknow Pit, but it was very muddy and formed a thick scale in the boiler which had to be chipped away every six weeks and was totally unfit for drinking. Drinking water was obtained from a natural spring about a kilometre away and had to be carted up the track by hand. In spite of these sparse resources one of Nobel’s first actions was to build a research and test centre which established the Ardeer research tradition which was to become a legendary centrepiece of technical excellence.

Research laboratory in Ardeer around 1880.

The first Nitroglycerine Hill, dynamite plant, nitric acid unit and laboratory (converted to the works manager’s house in 1879) were all contained in the original 400,000 square meters of the landward section of the site. The addition of a second Hill and a nitrocotton plant in 1881, and the construction of a third Hill in 1882 resulted in the expansion of the site to just over 1 square kilometre.

The period from 1887 to 1896 witnessed tremendous developments at the factory. During that time groups of buildings each associated with additional product developments grew up around the original factory, each one a considerable factory in its own right. In 1887 a branch railway line of the Glasgow and South Western Railway was laid right into the heart of the factory linking up with the national railway routes and opening up a whole new era of access. In the 1890s a further three Nitroglycerine Hills were established bringing the total to six. Finally, in the year and month of Alfred Nobel’s death, the workers were given the luxury of direct train access to a private railway station established at the factory and the period of isolation was over.

By 1902, the factory had grown to cover about one 1.5 square kilometres with 450 separate structures within which 1,200 people were employed. The growth had been assisted by the rapid expansion in export trade.

By this time, process steam was provided by an impressive central boiler house, and electricity and compressed air by the factory’s own power station. Narrow gauge railways were built to connect most parts of the site, which were also linked to the national railway network by the factory’s own sidings and marshalling yards. However, a large proportion of the factory’s output was now exported directly via its own jetty at the south-east end of the peninsula.

The factory continued to grow after Nobel’s death. Subsequent expansions enveloped the land to the north and the east of the original 400,000 square meters, crossing the River Garnock, the company even acquiring the Bogside Racecourse, once the venue for the Scottish Grand National. At its peak the factory covered an area of approximately 8 square kilometres. The employee payroll increased from the mere handful of 50 at its beginning to over 13,000 in its heyday, manufacturing all its own requirement of acids, ammonium nitrate and components importing only the very basic of raw materials and having an enviable independence from outside contract trades. The infrastructure was equally impressive, the site having its own power station, road and narrow gauge railway network as well as direct national rail links and marshalling yards.

The technological revolution that Nobel’s detonator and dynamite triggered was immediate and far-reaching and the embryonic industries he established had a meteoric rise which inevitably engendered intense commercial and corporate rivalry. Nobel’s Explosives Company and Ardeer were inevitably caught up in this corporate battlefield. The rivalry and competition reached a climax by 1883 in which year a palace revolution took place in Nobel’s Explosives. The then General Manager, A. A. Cuthbert resigned, and Thomas Reid was appointed Chairman and in 1884 was joined on the board by Charles Tennant, the head of the great Glasgow heavy chemicals firm based at St. Rollox: two strong personalities who had a profound effect on the emerging situation. Meanwhile Nobel’s other European enterprises had also prospered and, with equally strong personalities at the helm, antagonisms developed the solution to which was, as Nobel saw it, a fusion of all the Nobel Companies in Europe under a single overall control. Thomas Reid is credited with the idea that the best way to handle this situation was to set up a Trust Company. In this Nobel and Reid were of the one mind but, in the event, it was decided to set up two trust companies one in Paris the other in London. Thomas Reid together with Charles Tennant worked towards the implementation in the U. K. and set up the first trust company in London in 1886, The Nobel-Dynamite Trust Company.

This proved to be a very advanced form of business organisation the like of which had never been seen before in London. It was a holding company which effectively controlled the disposal of the assets of the members and had absolute authority over them even though the members were themselves separate corporate bodies. The group brought together:

Nobel Explosives (Scotland)

Four German union companies

The Mexican Nobel company

The Brazilian Nobel company

The Pacific Nobel Company

The Alliance Explosives Company

The South Wales Explosives Company

The Trust was an instant success and continued (with some changes) until the First World War when it was formally disbanded in 1915 for obvious reasons.

Finally the year 1926 saw the greatest fusion of chemical industries in the United Kingdom to that date in the merging of Nobel Industries with the other major chemical companies of Great Britain:

Brunner Mond and Company Ltd

British Alkali Company Ltd

British Dyestuffs Corporation Ltd

to form

IMPERIAL CHEMICAL INDUSTRIES (ICI).

First published 18 May 1998