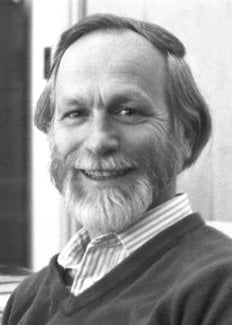

J. Michael Bishop

Biographical

“And what have kings that privates have not too,

Save ceremony, save general ceremony?”

William Shakespeare, in Henry the Fifth, IV. 1, 243-244

My youth held little forecast of a career in biomedical research. I was born on February 22, 1936, in York, Pennsylvania, and spent my childhood in a rural area on the west bank of the Susquehanna River. Those years were pastoral in two regards: I saw little of metropolitan life until I was past the age of twenty-one; and my youth was permeated with the concerns of my father’s occupation as a Lutheran minister, tending to two small parishes. My most tangible legacy from then is a passion for music, sired by the liturgy of the church, fostered by my parents through piano, organ and vocal lessons. I am deeply grateful for the legacy, albeit apostate from the church.

I obtained eight years of elementary education in a two-room school, where I encountered a stern but engaging teacher who awakened my intellect with instruction that would seem rigorous today in many colleges. History figured large in the curriculum, exciting for me what was to become an enduring interest. But I heard little of science, and what I did hear was exemplified by the collection and pressing of wild flowers. My high school was also small: eighty students graduated with me, few of whom eventually completed college. Tests conducted before I graduated predicted a future for me in journalism, forestry or the teaching of music; persons who know me well could recognize some truth in those seemingly errant prognoses.

I had taken naturally to school and was an excellent student from the beginning. But my aspirations for the future were formed outside the classroom. During the summer months of my high-school years, I befriended Dr. Robert Kough, a physician who cared for members of my family. Although he was practicing general medicine in a rural community when I met him, he was well equipped to arouse in me an interest not only in the life of a physician but in the fundaments of human biology. His influence was to have a lasting impact.

I entered Gettysburg College intent on preparing for medical school. But my ambition was far from resolute. Every new subject that I encountered in college proved a siren song. I imagined myself an historian, a philosopher, a novelist, rarely a scientist. But I stayed the course, completing my major in chemistry with diffidence but academic laurels. I met the woman who was to become my only wife. I have never been happier before or since.

I graduated from college still knowing nothing of original research in science. I knew that I would be going to medical school, but I had little interest in practicing medicine. Instead, under the influence of my college faculty, I had formed a vague hope of becoming an educator – by what means and in what subject, I knew not. Learning of this hope, an associate dean at the University of Pennsylvania recommended that I decline my admission to medical school there and, instead, accept an offer from Harvard Medical School. I followed the advice. My pastoral years were at an end.

Boston was a revelation and a revel. I could for the first time sate my burgeoning appetite for the fine arts. Harvard, on the other hand, was a revelation and a trial. I discovered that the path to an academic career in the biomedical sciences lay through research, not through teaching, and that I was probably least among my peers at Harvard in my preparation to travel that path. During my first two years of medical school, I acquired a respect for research from new-found friends among my classmates, particularly John Menninger (now at the University of Iowa) and Howard Berg (now at Harvard University). I sought summer work in a neurobiology laboratory at Harvard but was rebuffed because of my inexperience. I became ambivalent about continuing in medical school, yet at a loss for an alternative.

Two pathologists rescued me. Benjamin Castleman offered me a year of independent study in his department at the Massachusetts General Hospital, and Edgar Taft of that department took me into his research laboratory. There was little hope that I could do any investigation of substance during that year, and I did not. But I became a practiced pathologist, which gave me an immense academic advantage in the ensuing years of medical school. I found the leisure to marry. And I was riotously free to read and think, which led me to a new passion: molecular biology. The passion was to remain an abstraction for another four years, but my course was now set.

I was slowly becoming shrewd. I recognized that the inner sanctum of molecular biology was not accessible to me, that I would have to find an outer chamber in which to pursue my passion. I found animal virology, in the form of an elective course taken when I returned to my third year of medical school, and in the person of Elmer Pfefferkorn. From the course, I learned that the viruses of animal cells were ripe for study with the tools of molecular biology, yet still accessible to the likes of me. From Elmer, I learned the inebriation of research, the practice of rigor, and the art of disappointment.

I began my work with Elmer in odd hours snatched from the days and nights of my formal curriculum. But an enlightened dean gave me a larger opportunity when he approved my outrageous proposal to ignore the curriculum of my final year in medical school, to spend most of my time in the research laboratory. In the end, I completed only one of the courses normally required of fourth year students. Flexibility of this sort in the affaires of a medical school is rare, even now, in this allegedly more liberal age.

My work with Elmer was sheer joy, but it produced nothing of substance. I remained uncredentialed for postdoctoral work in research. So on graduation from medical school, I entered an essential interregnum of two years as a house physician at the Massachusetts General Hospital. That magnificent hospital admitted me to its prestigious training despite my woeful inexperience at the bedside, and despite my admission to the chief of service that I had no intention of ever practicing medicine. I have no evidence that they ever regretted their decision. Indeed, years later, I was privileged to receive their Warren Triennial Prize, one of my most treasured recognitions. I cherish the memories of my time there: I learned much of medicine, society and myself.

Clinical training behind me, I began research in earnest as a postdoctoral fellow in the Research Associate Training Program at the National Institutes of Health in Bethesda, Maryland, a program designed to train mere physicians like myself in fundamental research. In its prime, the Program was a unique resource, providing U.S. medical schools with many of the most accomplished faculty. Without the Program, it is unlikely that I could have found my way into the community of science.

My mentor at N.I.H. was Leon Levintow, who has continued as my friend and alter ego throughout the ensuing years. My subject was the replication of poliovirus, which had a test case for the view that the study of animal viruses could tease out the secrets of the vertebrate cell. I managed my first publishable research: my feet were now thoroughly wet; I had become confident of a future in research.

Midway through my postdoctoral training, Levintow departed for the faculty at the University of California, San Francisco (known to its devotees as UCSF). In his stead came Gebhard Koch, who soon lured me to his home base in Hamburg, Germany, for a year. And again, I had an enlightened benefactor: Karl Habel, who agreed to have N.I.H. pay my salary in Germany, even though I would be in only the first year of a permanent appointment. I repaid the benefaction by never returning to Bethesda.

My year in Germany saw little success in the laboratory, but I learned the joys of Romanesque architecture and German Expressionism. As my year in Germany drew to a close, I had two offers of faculty positions in hand: one at a prestigious university on the East coast of the United States, the other from Levintow and his departmental chairman, Ernest Jawetz, at UCSF. I chose the latter, easily, because the opportunities seemed so much greater: I would have been a mere embellishment on the East Coast; I was genuinely needed in San Francisco. In February of 1968, my wife and I moved from Hamburg to San Francisco, where we remain ensconced to this day.

I continued my work on poliovirus. But new departures were also in the offing. In the laboratory adjoining mine, I found Warren Levinson, who had set up a program to study Rous Sarcoma Virus, an archetype for what we now know as retroviruses. At the time, the replication of retroviruses was one of the great puzzles of animal virology. Levinson, Levintow and I joined forces in the hope of solving that puzzle. We were hardly begun before Howard Temin and David Baltimore announced that they had solved the puzzle with the discovery of reverse transcriptase.

The discovery of reverse transcriptase was sobering for me: a momentous secret of nature, mine for the taking, had eluded me. But I was also exhilarated because reverse transcriptase offered new handles on the replication of retroviruses, handles that I seized and deployed with a vengeance. I was joined in this work by a growing force of talented postdoctoral fellows and graduate students. Among our early achievements were a description of the mechanisms by which reverse transcriptase copies RNA into DNA, the characterization of viral RNA in infected cells, and the identification and description of viral DNA in both normal and infected cells.

The work on viral DNA was particularly notable because it was the handicraft of Harold Varmus, who had joined me as a postdoctoral fellow in late 1970. Harold’s arrival changed my life and career. Our relationship evolved rapidly to one of coequals, and the result was surely greater than the sum of the two parts. Together we decided to extend our interests beyond the problems of retroviral replication, to address the mystery of how Rous Sarcoma Virus transforms cells to neoplastic growth.

Others had shown that transformation by Rous Sarcoma Virus could be attributed to a single gene (eventually dubbed src) located near the 3′ end of the viral genome. Two problems engaged us: what was the origin of src; and what was the protein product of the gene? It was not our lot to find an answer for the second question, although we later played a part in discerning the biochemical function of the src protein. But with experiments performed mainly by Dominique Stehelin and Deborah Spector, we found the answer to the first question: src is a wayward version of a normal cellular gene (which we would now call a proto-oncogene), pirated into the retroviral genome by recombination (in a sequence of events known as transduction), and converted to a cancer gene by mutation.

In the years that followed, we consolidated our evidence for retroviral transduction, generalized the finding to retroviral oncogenes other than src, helped elucidate the sorts of genetic damage that convert normal cellular genes into cancer genes, explored the contributions of proto-oncogenes to the genesis of human cancer, added to the repertoire of proto-oncogenes by several experimental strategies, pursued the physiological functions of proto-oncogenes in normal organisms, and shared in the discovery of the protein kinase encoded by src.

I began my career at UCSF as an Assistant Professor of Microbiology and Immunology. I am now a Professor in the same department and in the Department of Biochemistry and Biophysics. I serve as Director of the G. W. Hooper Research Foundation and of the Program in Biological Sciences – the latter, an effort to unify graduate education at UCSF. I am as devoted to teaching as to research: I find the two vocations equally gratifying.

I am a member of the National Academy of Sciences, U.S.A; the American Academy of Arts and Sciences; the American Association for the Advancement of Science (elected an Honorary Fellow); the American Society for Biological Chemistry and Molecular Biology; the American Society for Microbiology; the American Society for Cell Biology; the American Society for Virology; the Federation of American Scientists; Alpha Omega Alpha; and Phi Beta Kappa.

My honors include several awards for teaching from the students and faculty of UCSF; a Doctor of Science Honoris Causa from Gettysburg College; the American Association of Medical Colleges Award for Distinguished Research; the California Scientist of the Year; the Albert Lasker Award for Basic Medical Research; the Passano Foundation Award; the Warren Triennial Prize from the Massachusetts General Hospital; the Armand Hammer Cancer Prize; the Alfred P. Sloan, Jr. Prize from the General Motors Cancer Foundation; the Gairdner Foundation International Award; the American Cancer Society National Medal of Honor; the Lila Gruber Cancer Research Award from the American Academy of Dermatology; the Dickson Prize in Medicine from the University of Pittsburgh; the American College of Physicians Award for Basic Medical Research; and the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for 1989. Most of these have been shared with Harold Varmus.

I am married to Kathryn Ione Putman and have two sons with her, Dylan Michael Dwight and Eliot John Putman. These three have given me a gift of affection and forebearance that I cannot hope to repay. My mother and father have reached their eighth and ninth decades, respectively, and were able to join us for a joyful time at the Nobel ceremonies in Stockholm. My brother, Stephen, is a distinguished solid-state physicist and now Professor at the University of Illinois; my sister, Catharine, is arguably the finest elementary school teacher in Virginia.

If offered reincarnation, I would choose the career of a performing musician with exceptional talent, preferably, in a string quartet. One life-time as a scientist is enough – great fun, but enough. I am a self-confessed book addict, an inveterate reader of virtually anything that comes to hand (with the notable exceptions of science fiction and crime novels). I enjoy writing and abhor the dreadful prose that afflicts much of the contemporary scientific literature.

This autobiography/biography was written at the time of the award and later published in the book series Les Prix Nobel/ Nobel Lectures/The Nobel Prizes. The information is sometimes updated with an addendum submitted by the Laureate.

Addendum, January 2018

J. Michael Bishop is University Professor, Director Emeritus of the G.W. Hooper Research Foundation and Chancellor Emeritus at the University of California, San Francisco (UCSF).

Michael was born and raised in rural Pennsylvania, and educated at Gettysburg College, Harvard Medical School and the Massachusetts General Hospital. He began his research career working on the replication of poliovirus, before shifting his attention to the fundamental mechanisms of tumorigenesis. Together with Harold Varmus he directed the research that led to the discovery of proto-oncogenes – normal genes that can be converted to cancer genes by genetic damage. This work eventually led to the recognition that all cancer arises from the malfunction of genes, and has provided new strategies for the study and management of cancer. Michael and Harold shared the 1989 Nobel Prize for Physiology or Medicine for their work.

Michael continues to study proto-oncogenes – their functions in normal cells and their role in the genesis of cancer. He has served as chair of the National Cancer Advisory Board, as a trustee of the Salk Institute for Biological Studies, as member of the Board of Directors for the Burroughs Wellcome Foundation, and as scientific advisor to a variety of granting agencies, research institutes and biotechnology firms.

For more biographical information, see:

Bishop, J. Michael, How to Win a Nobel Prize. An Unexpected Life in Science. Harvard University Press, London, 2003.

Nobel Prizes and laureates

Six prizes were awarded for achievements that have conferred the greatest benefit to humankind. The 14 laureates' work and discoveries range from quantum tunnelling to promoting democratic rights.

See them all presented here.