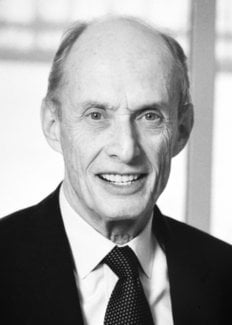

Paul Greengard

Biographical

My paternal great, great grandfather emigrated from Koenigsberg, currently Kaliningrad, to St. Louis during the 1850s, a time of large-scale movement of Germans, including German Jews, to the Mid-Western United States. My paternal grandfather moved to Binghamton, New York, where my father was born. My father had success in vaudeville as a singer/dancer/comedian. He eventually became a businessman working first in retail and then in wholesale in the cosmetics field.

I was born on December 11, 1925 in New York City under tragic circumstances – my mother, née Pearl Meister, died giving birth to me. My father remarried when I was 13 months old. In contrast to my mother, who had been Jewish, my stepmother, who raised me, was Episcopalian. From that time on I was brought up in the Christian tradition, celebrating Easter, Christmas, etc. I was prevented access to my biological mother’s family with whom I became familiar only very recently. I have been delighted to learn that many members of that family are highly creative individuals working in various fields of science, government, etc.

I attended public schools in Brooklyn and Queens. During World War II, I spent three years in the Navy as an electronics technician. After appropriate training, I was assigned to a team at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology that was involved in developing an early-warning system to intercept Japanese kamikaze planes before they could reach the ships of the U.S. fleet.

After the war, I attended Hamilton College, a small liberal arts college located in Clinton, New York, where I majored in mathematics and physics, and from which I graduated in 1948. I had been interested in going to graduate school in theoretical physics, but decided not to do so because at that time the only fellowship support for such graduate studies came from the Atomic Energy Commission. This was only three years after dropping the atomic bombs on Japan, and I didn’t want to contribute to research the fruits of which might contribute to creating more powerful weapons of mass destruction. In thinking about various options, I settled on the then nascent field of biophysics. At that time there were two groups of academic biophysicists. One, at the University of California, was engaged in biological and medical applications of radioisotopes. The other, at the University of Pennsylvania, headed by Detlev W. Bronk, used electrophysiological techniques to study nerve function. I chose the latter. Shortly after I arrived in Philadelphia, Bronk announced that he was accepting the Presidency of The Johns Hopkins University and invited a group of us to move there with him and form a new department of biophysics. The most senior member of the group was H. Keffer Hartline, who became Chairman of the Department of Biophysics at Johns Hopkins and who was later to win a Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for his work on vision. I did my first laboratory research under the supervision of Hartline.

Shortly after our move to Hopkins, Allen Hodgkin gave a lecture on the still unpublished work that he and Andrew Huxley had carried out on the ionic basis of the nerve impulse – work that was later recognized by the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine. That work, carried out exclusively with biophysical techniques, filled me with admiration. At the same time, the elegance of that study made me feel that it might be a long time until biophysical techniques would by themselves make further major contributions to our understanding of nerve cell function. Thus it was Hodgkin’s lecture that led me to consider combining biophysical and biochemical techniques to understand the molecular and cellular basis of how nerve cells work. Since, at that time, neuroscience as a field had not yet been created, my Ph.D. thesis was carried out under the joint supervision of Frank Brink, a distinguished biophysicist in our Department of Biophysics, and Sidney Colowick, a prominent biochemist who was a Professor in the Department of Biology – I remain to this day very grateful for their nurture and support.

Upon graduation from The Johns Hopkins University in 1953, I went to Europe for postdoctoral studies. My first year was with Henry McIlwain, at the Maudsley Hospital, of the University of London. My second year was with E.C. Slater, first at Cambridge University and then at the University of Amsterdam. At the end of my six-month period in Amsterdam, I returned to London to work in the laboratory of Wilhelm Feldberg, who was Head of the Department of Pharmacology at the National Institute for Medical Research at Mill Hill, London. At that time, the only departments that had both electrophysiological and biochemical facilities were pharmacology departments. Feldberg was a great scientist and a wonderful human being and provided an atmosphere in which I could continue to explore the relationships between biochemistry and electrophysiology in the nervous system. I seriously considered staying in England, which I found particularly compatible with my personality, which at that time was relatively reserved. However, the low level of financial support for scientific research in England, my ignorance of the nuances of the complex British educational system (two sons had been born in England), and the lack of central heating all conspired towards my returning to the United States. Upon my return, I spent one year working in the laboratory of Sidney Udenfriend at the NIH following which I became director of the Department of Biochemistry at the Geigy Research Laboratories. My prime motivation for going to Geigy was the prospect of applying basic scientific principles to the development of new drugs for the treatment of neurological and psychiatric disorders. Unfortunately, at that time, Geigy, like most, if not all, other pharmaceutical companies, was very conservative with regard to the nature of the research programs which they found acceptable. It was extremely difficult to obtain authorization to embark on innovative research approaches. In 1967, I left Geigy. After spending one year as a Visiting Professor, the first semester in Alfred Gilman’s Department of Pharmacology at Albert Einstein College of Medicine and the second semester with Sidney Colowick and Earl Sutherland at the Vanderbilt University School of Medicine, I took a position as Professor in the Department of Pharmacology at Yale University. My years at Yale saw the early development of my work on signal transduction in the nervous system. Although I was very happy throughout my 15 years at Yale, the offer to move to The Rockefeller University was irresistible and so I moved to New York in 1983 where I have been located since. It has been at Rockefeller that most of the work described in my Nobel Lecture was performed.

This autobiography/biography was written at the time of the award and later published in the book series Les Prix Nobel/ Nobel Lectures/The Nobel Prizes. The information is sometimes updated with an addendum submitted by the Laureate.

Paul Greengard died on 13 April 2019.

Nobel Prizes and laureates

Six prizes were awarded for achievements that have conferred the greatest benefit to humankind. The 14 laureates' work and discoveries range from quantum tunnelling to promoting democratic rights.

See them all presented here.