Nelson Mandela

Article

Nelson Mandela and the rainbow of culture

by Anders Hallengren*

This article was published on 11 September 2001.

Equality and pluralism

After 27 years in prison, Nelson Mandela negotiated the dismantling of the apartheid regime in South Africa, settled an agreement on universal suffrage and democratic elections, and became the first black president of the country in 1994. When he entered into office, he was aware of the universal importance of this success, but he was also humbled by the focus on his person as a symbol of international and historical dimensions. After all, during the years 1952-1990, he had made only three public appearances, and numerous people of different nations had contributed to the cause. Indeed, Africa had been liberated from colonialism during his prison years. The truth of the ancient Bantu adage umuntu ngumuntu ngabantu (we are people through other people) often came to his mind. And he saw, perhaps clearer than most of his contemporaries, the inevitability of “mutual interdependence” in the human condition, that “the common ground is greater and more enduring than the differences that divide.” The background of the development of this vision is remarkable and diverse. From his African heritage, from his country’s turbulent history, from his own formal education in “colonial” schools, and from his vicissitudes in the confines of Robben Island, Mandela emerged a man with a singular vision.

Solitary confinement. Mandela’s prison cell in the Robben Island penitentiary.

Photo: Anders Hallengren

The development of “colour-blindness”

Starting his fight for liberation of the blacks as an aggressive young African pugilist and nationalist in the early 1940’s, Mandela had not always deemed that democratic progress must rest on equality, pluralism, and multiethnicity. What made him later stand out from other South African leaders, and made him finally emerge victorious, was precisely his vision of a state that belongs equally to all its different peoples, nations, and tribes, whether Afrikaan, English, or Zulu. Being himself a leader belonging to the Xhosa-speaking people, he eventually transcended the idea of national liberty, and he attracted Indians, Jews, and other segments of the multicoloured population to the cause. Countering the racist suppression of the blacks, he avoided, unlike many other revolutionaries of the continent, acceding to a basically or exclusively black or tribal liberation movement.

This vision, sometimes referred to as “colour-blindness,” was partly inspired by Marxists, drawing on European ideologies and influenced from abroad. They were internationalists, not nationalists, and fought for a class, not for a race. The South African Communist Party, originally founded in 1920, and the kernel of which was a small group of Jewish immigrants and English nonconformists, was to influence the African National Congress (ANC) in such a direction, without ever succeeding in turning Nelson Mandela, Oliver Tambo, and other leaders into members of their party. This influence was theoretical and ideological, based on reading, hearsay, and revolutionary tradition. Through the years, it also became increasingly economic, in terms of financial support from parts of the communist, the socialist, and the social-democratic world — including Sweden, Norway, and India as well as the USSR. Mandela’s party, the ANC, was completely pragmatic in its views of material means, however. It accepted succour and aid wherever it came from, whether from Libya (as it happens, one of Mandela’s grandchildren was baptized “Gadaffi”), Iraq, diamond investors, or multinational corporations, sticking to its cause and never deviating from its course. The Sotho maxim “many rills make a big river” often was in Mandela’s mind. As a matter of fact, and quite contrary to contemporary European and American views, Nelson Mandela and the ANC remained ideologically independent while their financial dependence grew. Nevertheless, as a result of this focus and political imbalance, the ANC became a pawn in great-power politics, which delayed Mandela’s release and peaceful reform in South Africa until the winding-up of the Eastern bloc in 1989-90.

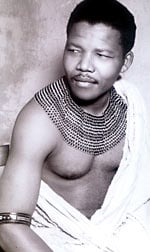

Transcending the idea of national liberty.

Courtesy of UWC-Robben Island Mayibuye Archives

The legacy of Mahatma Gandhi and Pandit Nehru

Another source of transnational perspectives and ideas of coexistence in harmony was the likewise oppressed Indian population of South Africa, many of whom traced their origin from the indentured labourers shipped to local sugar cane fields by the British colonial authorities. The confidence and faith of contemporary Indian freedom fighters rested upon the belief in the Satyagraha (truth-power) preached and put into effect by Mahatma Gandhi, a vision that had freed India in 1947. The vision of Gandhi was kept alive and thrived in South Africa, where Gandhi himself had lived and worked for many years (1893-1914). Nelson Mandela’s early encounters with these more peaceful Hindu, as well as Moslem, activists and their ideologies of emancipation seriously complicated his view of African liberation, and a close bond between the ANC and South Africa’s Indian population developed over time. This personal encounter with other people’s liberation movements in South Africa, eventually – almost of necessity, as it were – made the ANC leadership turn multicultural and multireligious, bound together by a common goal and based on that “common ground” Mandela often refers to.

When the present writer attended a function where Nelson Mandela received The Gandhi/King Award for Non-violence in 1999, the prize was presented by Ms. Ela Gandhi, granddaughter of Mahatma Gandhi and member of the South African Parliament. She described Mandela as “the man who completed the anti-colonial movement began by Mahatma Gandhi” and, indeed, “the living legacy of Mahatma Gandhi; the Gandhi of South Africa”. Furthermore, India on 16 March 2001 conferred The International Gandhi Peace Prize on Nelson Mandela at a grand ceremony at the presidential palace in New Delhi. “In honouring Mandela,” President Shri K.R. Narayanan said, “we are paying tribute to an unusual hero in the Gandhian mould, who personifies the triumph of the human spirit over forces of oppression.” In his acceptance speech, Mandela recalled India’s support to South Africa during the years of struggle against apartheid.

Penetrating even deeper into historical memory, Mohandas Karamchant Gandhi’s speech in Johannesburg in 1908 makes us aware of the persistent dream that propelled a progressive movement and is as yet to come true on a universal basis. On that occasion, Gandhi for the first time expressed his dream of a free South Africa, a vision that was to echo throughout the century:

“If we look into the future [of South Africa], is it not a heritage we have to leave to posterity, that all the different races commingle and produce a civilisation that perhaps the world has not yet seen?”

This speech is quoted in Gandhi and South Africa 1914-1948, a collection of articles edited by E.S. Reddy and Gopalkrishna Gandhi, published in India with the dedication “To Nelson Mandela and His Colleagues”. In that book, Gandhiji is in fact mentioned as “South Africa’s Gift to India.” M.K. Gandhi, Attorney in South Africa, was in a deep sense succeeded by Nelson Mandela, Johannesburg Attorney. Or, as Nelson Mandela said in September 1992, when he had been released from prison and democratic reform was on the agenda:

“Gandhiji was a South African and his memory deserves to be cherished now and in post-apartheid South Africa. We must never lose sight of the fact that the Gandhian philosophy may be a key to human survival in the twenty-first century.”

Manilal Gandhi, the son of Mahatma, remained in his father’s house in Natal, South Africa, and the Indian reform movement encouraged the chaotic but awakening civil disobedience campaigns shaking large parts of South Africa in the early 1950’s, in particular the Defiance Campaign of 1952, where the internal passport laws and other apartheid measures were challenged. These originally Indian-inspired peaceful resistance initiatives were met by violence, and the movements gradually turned underground, where they eventually grew. Finally the ANC reacted by building a military command, the Umkhonto we Sizwe (“Spear of the Nation”), preparing itself for guerrilla war. Contrary to Gandhi, and unlike the ANC leader Albert Lutuli, who received the Nobel Peace Prize in 1960, or Archbishop Desmund Tutu, Peace Prize Laureate of 1984, Nelson Mandela long felt forced to advocate unavoidable revolutionary violence, considering it as a counter-violence or a justified uprising against iniquitous laws. Mandela eventually dressed himself in camouflage uniform and was in combat training abroad (in Ethiopia), as were many other revolutionaries. Banned by the South African regime from attending public gatherings from late 1952 on, he nevertheless had efficiently and ingeniously continued his work as an organiser through undercover actions, escaping the police in ever-changing disguises, one of the favourites being that of a chauffeur. The years before his final imprisonment in 1962, he was nicknamed “The Black Pimpernel.”

Still, the Indian heritage of peaceful resistance was present in Mandela’s mind, and one of his closest fellow-combatants and conspirators was the Indian Ahmed Kathrada, with whom he was to spend a quarter of a century in jail. Among Mandela’s models and teachers, however, Jawaharlal Nehru – more militant than Gandhi and a politician of a practical turn – had become the prominent figure.

We should recall that his Indian friends evoked Mandela’s interest in India at the time when that state was in the process of being liberated from British colonialism. Nehru, who in 1947 became the first Prime Minister of India, had for two decades urged the Indians in South Africa to join forces with the black Africans, and India was the first country to introduce sanctions against the apartheid regime. One of Mandela’s most famous phrases and book titles, No Easy Walk to Freedom, was a quote from Nehru, whose hardships and determination he identified with. While in jail, Mandela was greatly encouraged by receiving the Indian Nehru Prize of 1979, and in his speech of thanks – in his absence read in New Delhi by the exiled Oliver Tambo – he emphasized his indebtedness to Nehru. Their fates were similar, too. When later on speaking of his release from prison, Nelson Mandela said: “I was helped when preparing for my release by the biography of Pandit Nehru, who wrote of what happens when you leave jail. My daughter Zinzi says that she grew up without a father, who, when he returned, became a father of the nation.”

The ancient African source of wisdom

The deeper basis for the development of Mandela’s universal vision and his confidence was his faith in education. More than everything else, Mandela emphasized education as important for his understanding, as well as for the growth of his people and the development of humanity in general. Furthermore, and consequently, he championed the availability of information and learning to all people. Part of his own peculiar schooling for life was, he points out, his long imprisonment as well as the ancient traditions of the Thembu people and his early years in missionary schools. If we venture to approach “the Making of Mandela,” the script that develops is his lifelong education, in a deep and singular way combining the core of African and European traditions.

Born in 1918 in the little village of Mvezo in Qunu in southern Transkei, as the son of the chief Gadla Henry Mphakanyiswa, Rolihlahla Mandela was the great-grandson of Ngubengcuka, the glorious king of the Thembu people who had died in 1832 before British occupation of the territory. Mandela’s clan, the Madiba, considered itself as dethroned royalty. The upbringing of the son was accordingly, and when his father died, the Thembu ruler Jongintaba and his wife No-England took care of the boy’s education.

The house where Mandela was born, in the Transkei district.

Courtesy of UWC-Robben Island Mayibuye Archives

A central concept in this Xhosa-speaking culture, as in Bantu tradition in general, is Ubuntu, fraternity. This implies compassion and open-mindedness and is opposed to individualism and egotism. Nelson Mandela learned how the belligerent and ruthless foreign occupants had destroyed the ancient peace and harmony that reigned among the different Xhosa tribes in the past. The effect was his persistent longing for the reestablishment of precolonial concord, the renaissance of the golden age of Africa. Accordingly, Mandela was always to prefer his clan name, Madiba, as his personal name. When he helped form the ANC Youth League in the Bantu Men’s Social Centre in Johannesburg 1944, the manifesto underscored that the African, in contrast to the white man, regards the universe as an organic whole in progress towards harmony, where individual parts exist only as aspects of this universal unity. There is continuity in this emphasis and in this African heritage, since the essence of the concept ubuntu was to recur and be expanded on in the new South African Constitution of 1996.

On the other hand, his mother Nosekeni Fanny had become a devout Christian and sent him to a missionary primary school (where he was given the English name Nelson). As a result, he was introduced and initiated into African teachings and traditions by his regal mentor, while at the same time he was the first ever in his family to attend the local Methodist school. His education had become pronouncedly Afro-European.

Learning the Western canon

The Methodist schools not only inspired the temperance and discipline of Mandela’s lifestyle but proved to be a training ground for liberation, even more so when he moved on to the Clarkebury School, which had been founded in 1825 under the rule of his ancestor king Ngubengcuka. Without these schools for Africans, there would have been neither transfer of power nor any black presidency, Mandela has pointed out.

He advanced to the all-British Healdtown High School, where the principal was a descendant of Lord Wellington, and then to the South African Native College at Fort Hare. There he encountered teachers who made an impression for life: Prof. Z.K. Matthews, the first black pupil to graduate from the college and a relative of Mandela; and the headmaster Alexander Kerr, who drilled the students in English literature. Matthews was to produce the ANC Freedom Charter. Kerr made the pupils see the relevance of classical European literature in a contemporary African context and got Mandela and his classmates to quote English poets wherever they went. Mandela was forever to praise his teachers, and these school experiences are part and parcel of the stress on education in the ANC Program of Action of 1949, which, in its basic aims, established the educational means and the cultural ends of liberation:

– To unite the cultural with the educational and national struggle;

– To establish a national academy of arts and sciences.

After Healdtown followed studies in law and social sciences at Witwaterstand University in 1943-49. These were never officially finished but were taken up again when, as with some other prisoners, he was later allowed to study through correspondence at the University of South Africa and, in 1980, at London University. In fact, the real school for life started when he was arrested in 1962, and indeed this is literally true, since he spent the next thirty years studying and teaching.

Robben Island University

Capetown seen from the Nelson Mandela Gateway to Robben Island.

Photo: Anders Hallengren

Robben Island became a campus for political prisoners. They had to work outdoors in an isolated lime quarry, where, when left to themselves in mine shafts, they discussed their different views and taught each other what they knew, year after year. Mandela wanted the spirit of a university to reign, and regular lectures were arranged in secrecy. Thus, the prison would be called ‘The Robben Island University’ or later, ‘Nelson Mandela University’. From debates with prisoners and white warders through the years, Mandela grew to a widened ideological awareness from which he would draw when arguing with the government on a new South African constitution. In particular, he studied Afrikaans and learnt to understand the mind-set of the Boer minority through discussions with warders and staff. Mandela identified with these descendants of Dutch seventeenth-century immigrants and saw that he himself, under other circumstances, could have taken views similar to theirs. And he always appreciated their fight against the English in the Boer War, which seemed partly to parallel and herald his own fight against oppression. From this understanding, Mandela’s remarkable spirit of reconciliation was drawn, when Africans and Afrikaners finally formed a coalition government.

Mandela saw historical connections in all present events, and he knew that the British had imprisoned Xhosa chiefs at Robben Island already in the early nineteenth century. These ancestors and predecessors, first and foremost among them the ruler Makanna, whose warriors had almost conquered the English at Grahamstown in 1819, made him feel the long and strong line behind him, pressing and urging him onwards.

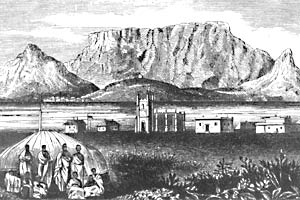

Xhosa chiefs imprisoned at Robben Island in the 19th century. Apart from the Anglican Church, there was also a leper colony on the island.

Wangermann engraving from 1868 in the South African Library/Robben Island Museum

As times went by, the prisoners found more and more ways of communicating with each other, and the interchange of ideas and knowledge grew. They formed a motley company, where the variety proved to be a great asset to them all. There was the famous South African poet Dennis Brutus, a constant source of inspiration. There were the most foul-mouthed felons as well as an intellectual elite. As important as the presence of African culture, however, was the society of dead English poets.

Shakespeare the revolutionary

If Africa was the source of their illumination, European literature served as a propelling dynamo for their nerve. Of particular pertinence was William Shakespeare, who was constantly quoted and discussed. Were they not wronged and deceived by a criminal ruler as had been Hamlet, the Prince of Denmark? The subject is of a treacherous Macbeth, and like Macbeth was not the South African regime doomed to destruction? Or, were they not rightfully conspiring against a despotic Julius Caesar? Did not the future rest upon them? Did they really have the guts to shoulder their responsibility? Already an ANC Youth League flyer of 1944 had concluded in the summoning words of Julius Caesar:

The fault … is not in our stars,

But in ourselves, that we are underlings.

The Bible and Shakespeare: the missionary schools had been effective. The Pan African Congress President Robert Sobukwe had translated Shakespeare’s Macbeth into Zulu, just as Tanzania’s liberator Julius Nyerere had translated Julius Caesar (for whom he was named) into Swahili. Shakespeare was an active part in the political play. When Harold Macmillan, the conservative premier of England, had delivered a speech in Capetown in 1960, a newspaper cartoon pictured him afterwards with a caption picked from Julius Caesar:

O! pardon me, thou bleeding piece of earth,

That I am meek and gentle with these butchers.

Mandela, who always forgave but never forgot, was to refer to this political cartoon when he spoke in London in 1996. In jail, Mandela’s extraordinary memory was a mine, and to him, Shakespeare was The Writer. While in custody, a subject of debate could be whether George Bernard Shaw could measure up to Shakespeare. When Mandela was waiting for the final verdict after the extended legal proceedings, and was prepared to be sentenced to death, Shakespeare’s counsel in Measure for Measure was a source of courage:

Be absolute for death; either death or life

Shall thereby be the sweeter.

Unlike the Bible, the Quran, the Bhagavadgita, or Das Kapital by Karl Marx, Shakespeare was a common denominator for the prisoners at Robben Island. Only a few of them were Christian believers; a few were Moslems or Hindus; a few, communists; and their origins were different. They all knew Shakespeare, however. Furthermore, from the point of view of the penitentiary authorities, four-hundred-year-old Elizabethan dramas were not considered dangerous reading. But Shakespeare was profoundly political and always had something of acute importance to say. Militant passages drawn from Coriolanus or Henry V excited them, and Julius Caesar stirred them to rebellion. They knew their destiny, and Mandela’s favourite passage read:

Cowards die many times before their deaths;

The valiant never taste of death but once.

Free to study classical drama, the prisoners at Robben Island staged a more than two-thousand-year-old Greek tragedy, the Antigone by Sophocles, in which earthly power is challenged with reference to a higher law. In that production, which was presented under lock and key, Mandela played the part of Creon, the tyrant.

The lime quarry at Robben Island where prisoners taught each other, recited poems and presented lectures. Due to the extreme light and dust, most prisoners suffered from “snow blindness”. Nelson Mandela had to undergo surgery to restore the lachrymal ducts of his chronically inflamed eyes and to this day is blinded by flashlights.

Photo: Anders Hallengren

In fact, Mandela began thinking of political organization in terms of dramaturgy. In late June 1976, he noted: “It is often desirable for one not to describe events, but to put the reader in the atmosphere in which the whole drama was played out right inside the theatre, so that he can see with his own eyes the actual stage, all the actors and their costumes, follow their movements, listen to what they say and sing, and to study the facial expressions and the spontaneous reaction of the audience as the drama unfolds.” Thabo Mbeki, Ahmed Kathrada, Walter Sisulu, Neville Alexander, and all the others were inspired by words that clearly expressed their thoughts and notions, and at once these became tools in a revolutionary process and cutting rejoinders on a political scene.

From Henley to Heaney

Another source of encouragement was the words of a Victorian English poet, William Ernest Henley (1849-1903). Decade after decade, the unforgettable lines of the poem Invictus, “unconquerable,” were on Mandela’s lips:

Out of the night that covers me,

Black as the Pit from pole to pole,

I thank whatever gods may be

For my unconquerable soul.In the fell clutch of circumstance

I have not winced nor cried aloud.

Under the bludgeonings of chance

My head is bloody, but unbowed.Beyond this place of wrath and tears

Looms but the Horror of the shade,

And yet the menace of the years

Finds, and shall find, me unafraid.It matters not how strait the gate,

How charged with punishments the scroll,

I am the master of my fate:

I am the captain of my soul.

At Robben Island, Mandela recited this poem and taught other prisoners these defiant lines; reading such words “puts life in you”, Mandela says. From the British philosopher Bertrand Russell, who had been jailed for his protests against nuclear weapons, Mandela had drawn the arguments of defiance, when conscience and civil laws do not agree. From the Russian novelist and idealist Lev Tolstoy, Kathrada and Mandela got similar support. At times, they also identified with the endless waiting of the protagonists in Samuel Beckett‘s play Waiting for Godot.

Prisoners crushing stone at the Robben Island B-Section courtyard.

Courtesy of UWC-Robben Island Mayibuye Archives

This literary heritage came with an awareness of the blackness derived from the same source – an often-discussed paradox: they were fighting foreign rule with foreign maxims. Among Xhosa poets, Mandela’s favourite was Krune Mkwayi (Mqhayi), whose haunting lament to the Prince of Wales in 1925 has been translated into English by Robert Mshengu Kavanagh:

You sent us the truth, denied us the truth;

You sent us the life, deprived us of life;

You sent us the light, we sit in the dark,

Shivering, benighted in the bright noonday sun.

They were also heartened by the existence of contemporary South African authors like Nadine Gordimer, a devoted supporter. But when they were released and a new government was formed, in which prisoners were transformed into ministers of state, they still quoted English poetry, such as the lines of the contemporary Nobel Laureate Seamus Heaney:

The longed-for tidal wave

of justice can rise up,

And hope and history rhyme

The liberation of faith

In December 1999, the Parliament of the World’s Religions assembled for the third time since 1893, this time in Capetown. Mandela, who was scheduled to go to the United States, changed his itinerary, anxious to attend. He considered the event of utmost importance. He also had something he wanted to say. In his concluding speech, delivered on December 5, he pointed out the importance of religion to the liberation of his country and his own indebtedness, countering the propaganda that had for half a century pictured him as a godless infidel:

“In our country, my generation is the product of religious education. We grew up at a time when the government of this country owed its duty only to whites, a minority of less than fifteen percent. They took no interest whatsoever in our education. It was religious institutions, whether Christian, Moslem, Hindu, or Jewish, in the context of our country; they are the people who bought land, who built schools, who employed teachers and paid them. Without church, without religious institutions, I would never have been here today. It was for that reason, that when I was ready to go to the United States on the first of this month, an engagement which had been arranged for quite some time, when my comrade, Ibrahim, told me about this occasion, I said: I will change my own itinerary, so I will have the opportunity of appearing here. But I must also add, that I appreciate the importance of religion. Apart from the background I have given you, you have to have been in a South African jail under apartheid, where you can see a cruelty of human beings to others in a naked form. But it was again religious institutions, Hindus, Moslems, leaders of the Jewish faith, Christians, it was them who gave us the hope that one day, we would come out, we would return. And in prison, the religious institutions, raised funds for our children, who were arrested in thousands and thrown into jail, and many of them one day left prison at a high level of education, because of this support we got from religious institutions. And that is why we so respect religious institutions. And we try as much as we can to read the literature, which outlines the fundamental principles of human behaviour. And, like the Bhagadgita, the Qur’an, the Bible, and other important religious documents. And I say this, so you should understand, that the propaganda that has been made for example about the liberation movement is completely untrue. Because religion was one of the motivating factors in everything that we did.”

Mandela also looked onwards. Concerning the prospects of the twenty-first century, he pointed out: “No less than in any other period of history, religion will have a crucial role to play in guiding and inspiring humanity to meet the enormous challenges that we face.”

The rainbow government

In conclusion, the outlook and horizon of Mandela and his sympathisers, who were to form the ideological centre of the new administration of 1994, was stamped by East and West, by European and Asian, as well as genuine African influences. This eclecticism cohered and interacted with the cultural variety of their country and their different origins, which propelled their joint endeavours. The final outcome was the Rainbow Nation, the most multiethnic government ever formed.

Successfully curbing and harnessing the indlovu ayipatha, the dangerous elephant in the shape of the apartheid regime, the rebels finally reached their goal and settled the dispute between Africans and Afrikaners. In achieving this, Mandela agitated against black domination. He did not argue for a turning back to a glorious African society of bygone times but called for a completely new kind of state, a multiethnic democracy without match, constituted by a manifold of cultures having equal rights.

Thus, the ANC leadership, as reorganized when Mandela was released in 1990 and could officially take on command, consisted of a cross section of races, including seven Indians, seven “Coloureds,” and seven whites. Likewise, and in harmony with this, a broad cultural and political basis marked the government of 1994. Ministers of state were blacks, whites, Indians, Coloureds, Muslims, Christians, communists, liberals, conservatives. Apart from three Indian Muslims, there were two Hindus in Mandela’s government. Never had such a cabinet been seen in Africa or elsewhere. Many prominent posts were occupied by neither Africans nor by Afrikaners: there were Dullah Omar, Minister of Justice; the Minister of Water Kader Asmal; the Minister of Finance Trevor Manuel … all widening the arch of the rainbow government.

The rights of the people shall be the same, regardless of race, colour or sex.

Photo: Anders Hallengren

This was the realization of a political program outlined almost half a century earlier. The date can be determined with some certainty. In “The Programme of Action: Statement of Policy Adopted at the ANC Annual Conference 17 December 1949,” there is hardly a trace of the future multicultural view. In The Freedom Charter, however, adopted at the Congress of the People, Kliptown, on 26 June 1955, the ideology is emerging:

“The rights of the people shall be the same, regardless of race, colour or sex … All National Groups Shall have Equal Rights! … Men and women of all races shall receive equal pay for equal work;”

The idea is explicit but not yet fully developed in Mandela’s speech for the defence from the dock at the Rivonia Trial in 1963, where he emphasized, “I have fought against white domination and I have fought against black domination. I have cherished the ideal of a democratic and free society in which all persons live together in harmony and with equal opportunities.” In his speech in Harlem, New York, in June 1990, the recently discharged prisoner repeated these words, adding, “Death to racism! Glory to the sisterhood and brotherhood of peoples throughout the world!” The basic concept of ubuntu had by then been expanded beyond all limits of nation, race, faith and gender.

The deed and document of this ideology is the 1996 Constitution of the Republic of South Africa, one of the most modern and radical in the world regarding human rights. It includes an extensive Bill of Rights (Ch. 2) where the numerous paragraphs on equality stand out, for example, “The state may not unfairly discriminate directly or indirectly against anyone on one or more grounds, including race, gender, sex, pregnancy, marital status, ethnic or social origin, colour, sexual orientation, age, disability, religion, conscience, belief, culture, language and birth.” In Ch. 1, “Founding Provisions,” the official languages are enumerated; all are permitted for national government and provincial government use: “The official languages of the Republic are Sepedi, Sesotho, Setswana, siSwati, Tshivenda, Xitsonga, Afrikaans, English, isiNdebele, isiXhosa and isiZulu.”

It also states that the president determines the national anthem of the Republic by proclamation. Such proclamation had already occurred. Today, Nkosi Sikelel’ iAfrika, the old song of the revolutionaries, sang by Mandela and his comrades decade after decade, echoes throughout the republic in its chorus of equal tongues. The first line concludes the Preamble of the Constitution:

Nkosi Sikelel’ iAfrika

Morena boloka setjhaba sa heso

God se‘n Suid-Afrika

Mudzimu fhatutshedza Afurika

Hosi katekisa Afrika

God bless South Africa.

Educational goals

The Constitution, which is also supplemented by an Action Plan, stresses the importance of education, mentioning this already in the Bill of Rights:

“Everyone has the right –

a. to a basic education, including adult basic education; and

b. to further education, which the state, through reasonable measures, must make progressively available and accessible.”

Again, the Constitution of 1996 can be seen as the fulfilment of the ANC Freedom Charter of 1955:

“All people shall have equal right to use their own languages, and to develop their own folk culture and customs . . . The aim of education shall be to teach the youth to love their people and their culture, to honour human brotherhood, liberty and peace; Education shall be free, compulsory, universal and equal for all children; Higher education and technical training shall be opened to all by means of state allowances and scholarships awarded on the basis of merit; Adult illiteracy shall be ended by a mass state education plan.”

In this spirit, people today may enter The Nelson Mandela Gateway to Robben Island Museum Heritage Services (and its iconic museum building completed in December 2001) and go by boat to the penitentiary which Mandela turned into a university. At Robben Island, we also find the model Robben Island Primary School, a school of integration and international awareness.

A school where the African past is always present. Robben Island Primary School serves as a model school for integration and international awareness.

Photo: Anders Hallengren

What’s in a name?

Mandela never wanted places and things to be named after him. The few exceptions are schools and educational institutions, such as the Nelson Mandela School of Medicine in Durban and Dr. Nelson Mandela High School in the Western Cape; or, to look abroad, ‘Nelson Mandela School’ in the German Democratic Republic, founded in 1984, and Nelson Mandela School of Public Policy and Urban Affairs in Baton Rouge, LA, USA.

A significant and very telling feature, however, witnessing his care for the future generations, is the Nelson Mandela Children’s Fund, established when President Nelson Mandela pledged one-third of his salary for five years.

Conclusion

Thus, we see how one man’s remarkable life has reached its fulfillment and has blossomed into a national vision. Inspired by myriad influences, taking the best from both his native heritage, from the example of foreign freedom movements, and even from the history and literature of his oppressors, Nelson Mandela forged a vision of humanity that encompasses all peoples and that sets the hallmark for the rest of the world.

When the Norwegian Nobel Committee decided to award the Nobel Peace Prize for 1993 to Nelson R. Mandela and Frederik Willem de Klerk, it was pointed out that their achievement was made by “looking ahead to South African reconciliation instead of back at the deep wounds of the past.” The committee also observed that South Africa has been the very symbol of racially conditioned suppression, and that the peaceful termination of the apartheid regime accordingly “points the way to the peaceful resolution of similar deep-rooted conflicts elsewhere in the world.”

In his Nobel Lecture, Nelson Mandela referred to the organic world-view expressed already in the manifesto of 1944, calling himself a mere representative of the millions of people across the globe who “recognised that an injury to one is an injury to all;” which is the essence of ubuntu philosophy universally applied.

* Anders Hallengren (1950–2024) was an associate professor and research fellow in the Dept. of History of Literature and the History of Ideas at Stockholm University. He served as consulting editor for literature at Nobelprize.org.

As a travelling journalist of international affairs in the 1980s and the 1990s, Anders Hallengren saw several African leaders, presidents as well as revolutionaries, including Nelson Mandela and Alfred Nzo, former General Secretary of the ANC. In 1984, Hallengren published a book on the postcolonial tug-of-war over Africa (Cuba in Africa: A Turning Point in Great-Power Politics – Decolonization and Détente in Conflict).

He has been a visiting fellow in the Dept. of History at Harvard University, and a visiting professor in the Dept. of Philosophy, University of Hawaii. Dr. Hallengren has lectured on human rights history at the Indira Gandhi Centre in New Delhi, as well as at the Good Hope Centre in Cape Town, South Africa. For many years he served as a connection and advisor of the American-Russian Transnational Institute.

First published 11 September 2001

Nobel Prizes and laureates

Six prizes were awarded for achievements that have conferred the greatest benefit to humankind. The 14 laureates' work and discoveries range from quantum tunnelling to promoting democratic rights.

See them all presented here.