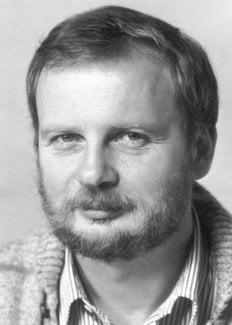

Hartmut Michel

Biographical

I was born in Ludwigsburg, Württemberg, in the southwestern part of the Federal Republic of Germany on July 18, 1948, as the elder son of Karl and Frieda Michel. My ancestors lived in that area for generations, mainly as farmers. There the inherited land is equally divided among sisters and brothers, and not enough land was left for one family’s living during my grandparents’ generation. During the day my father worked in a factory as a joiner, my mother at home as a dressmaker, in the evenings and on Saturdays care had to be taken of the huge gardens.

As a child I liked to play outside, to stroll through the fields, and I was an active member of the local children’s gang, frequently being chased by field guards and building supervisors. Nevertheless, my performance at school was very good, and mainly due to the influence of my mother I was allowed to attend high school. At age eleven I became a member of the circulating library of my home town. From there on I was rarely seen outside, but was reading two to four books per week, the subjects ranging from archaeology over ethnology and geography to zoology. Needless to say that I did not do much homework. At school my favorite subjects were history, biology, chemistry and physics. Especially the teaching in physics was excellent. Most of my understanding of it I got at high school, not at the university.

In parallel, my interest in molecular biology rose. In 1969 – after the obligatory military service – I applied to study biochemistry at the University of Tübingen. At that time Tübingen was the only place in Germany, where one could study biochemistry from the first year, and I was happy to be accepted. Studying biochemistry meant that one had to take part in nearly the same amount of lectures and courses as chemistry students in addition to numerous lectures and courses in biology. The atmosphere between senior teachers and students was impersonal, and the only time I talked to the full professor of biochemistry was during the final examination. However, the possibility existed to work for one year in the various biochemistry labs at the University of Munich and the Max-Planck-Institut für Biochemie instead of attending lab courses in Tübingen. I took that chance in 1972/1973, and at the end I was convinced that academic research was what I wanted to do.

After the examination in Tübingen in 1974 I did the experimental part of my biochemistry diploma in Dieter Oesterhelt’s lab at the Friedrich Miescher-Laboratorium of the Max-Planck-Gesellschaft in Tübingen. In cooperation with Walter Stockenius, Dieter Oesterhelt had discovered bacteriorhodopsin in halobacteria and later proposed that it acts as a lightdriven proton pump in the framework of Peter Mitchell’s chemiosmotic theory. During my diploma work I characterized the ATPase-activity of halobacteria. In 1975, Dieter Oesterhelt moved to Würzburg. I joined him, and as a thesis I correlated the intracellular levels of adenosine di- and triphosphate with the electrochemical proton gradient across the halobacterial cell membrane. Having received the doctorate in June 1977 I tried to fuse delipidated bacteriorhodopsin with bacterial vesicles in order to achieve light-driven amino acid uptake. Upon storage in the freezer the delipidated bacteriorhodopsin yielded solid, glass-like aggregates. On the basis of this observation I was convinced that it should be possible to crystallize membrane proteins like bacteriorhodopsin, which was considered to be impossible at that time. With Oesterhelt’s help I started the experiments, and already four weeks later we obtained a new two-dimensional membrane crystal of bacteriorhodopsin. It was not the three-dimensional crystal we wanted, but allowed me to travel to the MRC at Cambridge, England, and to do electron microscopical studies together with Richard Henderson. Back in Würzburg, we observed the first real three-dimensional crystals of bacteriorhodopsin in April 1979. The success led me to cancel my plans to do post-doctoral studies with Susumu Ohno, Duarte, California, on sexual differentiation in mammals. Instead of this, I moved with Dieter Oesterhelt again, this time to the Max-Planck-Institut für Biochemie at Martinsried near Munich, where he became a department head and director. Before moving to Munich, Ilona Leger became my wife. Her understanding and patience helped me a lot.

A promising aspect of the move to Martinsried was the possibility of a cooperation with Robert Huber and colleagues, who at the Max-Planck-Institut had established a very productive department for X-ray crystallographic protein structure analysis. Our bacteriorhodopsin crystals were found to diffract X-rays, but to be too small and too disordered for a structural analysis. We tried to improve size and quality of the crystals. Since all the X-ray crystallographers had beautifully diffracting crystals of soluble proteins, I, understandably, had very limited access to the X-ray equipment at Martinsried. As a consequence, I spent four months at the MRC in Cambridge, England, together with Richard Henderson in 1980, in order to perform X-ray experiments. This period was essential for improving the crystallization method. After my return Dieter Oesterhelt decided to buy an X-ray generator for the ongoing work with bacteriorhodopsin. The generator was installed in Robert Huber’s department and guaranteed us continued access to the equipment, and the know how, of the X-ray crystallographers. Later on, I used this generator for the work with the reaction centres.

Frustrated from the lack of the final success with bacteriorhodopsin, I tried to crystallize several other membrane proteins, mainly photosynthetic ones. After developing a new isolation procedure I obtained the first crystals of the photosynthetic reaction centre from the purple bacterium Rhodopseudomonas viridis at the end of July 1981. One week later our daughter Andrea was born. During September 1981 the first reaction centre crystal was X-rayed by Wolfram Bode and myself, and turned out to be of excellent quality. Therefore 1981 was the happiest and most successful year of my life.

Dieter Oesterhelt immediately agreed that the reaction centre should be a project of the young people. In February 1982, I started the data collection for the X-ray structure analysis. In April or May I gave a seminar in Robert Huber’s department and asked officially for collaboration. After some internal discussions Robert Huber agreed that Johann (“Hans”) Deisenhofer, who was the partner of my choice, should take part in the reaction centre project. During the work Hans and I became the best friends. In August 1982, Hans and Kunio Miki, a Japanese post-doctoral research associate in Robert Huber’s department, started to evaluate the pile of X-ray films. I continued with the experimental work, occasionally helped by Robert Huber, who showed me how the diffraction pattern of a promising derivative should look like. Not only the X-ray work, but also the entire biochemical characterization and sequence determination had to be done. After the preliminary tracing of the peptide chains by Johann Deisenhofer, the sequence determination, which was performed by Karl A. Weyer, Heidi Gruenberg and myself with Dieter Oesterhelt’s support and help, turned out to be the bottle neck for our progress. During that period of heavy work our son Robert Joachim was born in 1984.

As one of the results of the success I received many offers. I accepted the one to become a department head and director at the Max-Planck-Institut für Biophysik in Frankfurt/Main, West Germany, where I am since October 1987.

For the success with the crystallization of membrane proteins and the elucidation of the three-dimensional structure of the photosynthetic reaction centre from the purple bacterium Rhodopseudomonas viridis I received various prizes and awards. Among these are the Biophysics Prize of the American Physical Society (together with d. Deisenhofer), the “Chemiedozentenstipendium” of the “Fonds der Chemischen Industrie”, the “Otto Klung-Preis” for chemistry, the Leibniz-Preis of the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft, the “Otto-Bayer-Preis” (together with J. Deisenhofer) and now the Nobel Prize (together with J. Deisenhofer and R. Huber).

This autobiography/biography was written at the time of the award and first published in the book series Les Prix Nobel. It was later edited and republished in Nobel Lectures. To cite this document, always state the source as shown above.

Addendum, April 2025

In 2007 I married Elena Olkhova, a biophysicist. More happy days came: We got a daughter, Margarita Caroline Michel, in 2010. She turns out not only to be a very good student but to be also a talented promising young pianist. In 2022 I retired from my position as department head and director at the Max Planck Institute of Biophysics, but I continue to work as a leader of an emeritus research group. We mainly study the consumption of molecular oxygen by living organisms, its reduction to water and energy conversion. We hope to be able to use our knowledge to fight infectious diseases like tuberculosis.

Nobel Prizes and laureates

Six prizes were awarded for achievements that have conferred the greatest benefit to humankind. The 14 laureates' work and discoveries range from quantum tunnelling to promoting democratic rights.

See them all presented here.