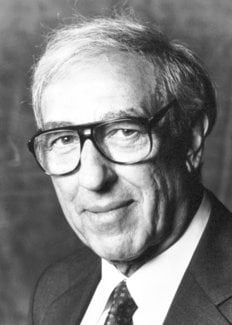

Edmond H. Fischer

Biographical

Memories of my early childhood are clouded with uncertainties because I was essentially separated from my parents since the early age of seven. I was born in Shanghai, China on April 6, 1920. My father had come there from Vienna, Austria after earning doctorates in law and business. My mother, born Renée Tapernoux, had arrived from France with her parents via Hanoi. Her father had left Switzerland as a young man to become a journalist for L’Aurore. This journal published the letter by Emile Zola entitled “J’accuse” in which he denounced the government cover-up during the Affaire Dreyfus which tore France apart at the turn of the century. When the case against Dreyfus collapsed in the early 1900s my grandfather left for French Indochina, then called le Tonkin. He later went to Shanghai where he founded the “Courrier de Chine”, the first French newspaper published in China. He also helped to establish “l’Ecole Municipale Française” where I first went to school.

At age 7, my parents sent my two older brothers and me to La Châtaigneraie, a large Swiss boarding school overlooking Lake Geneva. My oldest brother, Raoul, was the first to leave to attend the ETH, the Swiss Federal Polytechnical Institute in Zürich where he was awarded a degree in engineering. My brother Georges went to Oxford and read law.

In 1935, I entered Geneva’s all boys Collège de Calvin from which I obtained my Maturité Fédérale four years later, even as the specter of World War II loomed evermore menacing. While in school, I formed a lifelong friendship with my classmate Wilfried Haudenschild who dazzled me with his tinkering abilities, off-the-wall ideas and mechanical inventiveness. Together we decided that one of us should go into the Sciences and the other into Medicine so that we could cure all the ills of the world.

Another important event marked my High School days: I was admitted to the Geneva Conservatory of Music. I had heard Johnny Aubert give an unforgettable rendition of Beethoven’s 5th Piano Concerto. I decided on the spot that I wanted to study with him. After an audition in which I nervously presented Mendelssohn’s Rondo Capriccioso and Chopin’s A-maj. Polonaise, he took me on, and that spelled the beginning of many enthralling years. Music had always played an important part in my life, to such an extent that I even wondered whether I should not make a career of it. But finally I thought it better to keep music purely for pleasure.

It was my goal to become a microbiologist but Fernand Chodat, the Professeur of Bacteriology, argued that there was little future in that field, which was probably the case in Switzerland at that time. He advised me to get a diploma in Chemistry saying that, in any case, test tubes were of more use than a microscope to modern microbiologists.

I therefore entered the School of Chemistry just at the start of World War II. Two years of quantitative inorganic analyses seemed endless. Organic chemistry finally arrived like a breath of fresh air, if not a reprieve on life. I earned two Licences ès Sciences, one in Biology, the other in Chemistry and, two years later, the Diploma of “Ingénieur Chimiste”. For my thesis, I elected to work with Prof. Kurt H. Meyer, Head of the Department of Organic Chemistry. “Le Patron” as we affectionately called him, was a most impressive person. At the time when most scientists showed little understanding of natural high polymers, Kurt Meyer had already authored several books on the subject, starting with the epochal “Meyer-Mark: Der Aufbau der hochpolymeren organischen Naturstoffe” and “Makromolekulare Chemie”. His main interest lay in the structure of polysaccharides, particularly starch and glycogen. To unravel the structure of these molecules, enzymes were needed: alpha- and beta-amylases, phosphorylase, etc. Therefore, the lab was divided into two groups: the enzymologists under the guidance of Peter Bernfeld and carbohydrate chemists under Roger Jeanloz. I decided to work on the purification of hog pancreas amylase. Within a couple of years, we succeeded in crystallizing alpha-amylase from pork pancreas and soon after that, from a variety of other sources including human pancreas and saliva, two strains of A. oryzae, B. subtilis and P. saccharophila. It is at that time that Eric A. Stein joined the laboratory, beginning a marvelous 15-year collaboration and a lifelong friendship.

It had always been my intention to go to the United States to pursue my studies in Biochemistry. In those days, that field was in its infancy in most European universities to such an extent that I was asked to present the very first course in Enzymology as a Privat Docent at the University of Geneva in 1950. Two events hastened my departure for the USA: the untimely death of Kurt Meyer following an asthma attack and my being abruptly issued a US immigration visa. Apparently, the US consulates abroad were clearing their files before the complicated McCarran Act would come into effect. I had decided to go to CalTech on a Swiss Post-doctoral Fellowship that Professor Paul Karrer succeeded in securing for me on a moment’s notice. Some friends who knew of my arrival in New York had arranged for me to give some seminars on my way to Pasadena: Maria Fuld at Pittsburgh and Henry Lardy at Madison. To my utter surprise, I was offered a job in both places. Then, upon my arrival at CalTech I found a letter from Hans Neurath, Chairman of the Department of Biochemistry at the University of Washington, inviting me to come to Seattle, apparently for the same purpose. I thought that the Americans had to be crazy since at that time, academic positions in Europe were one-in-a-million. I visited Seattle with my wife and thought that the surrounding mountains, forests and lakes were beautiful, reminiscent of Switzerland. The Medical School was brand-new and when I was offered an Assistant Professorship, I accepted and have never regretted that decision.

There were only seven of us on the faculty and we quickly became close friends. I remember the amused expressions of my colleagues seated in the back row of the class listening to my fractured English when lecturing the medical students. I also remember Ed Krebs‘ broad smile whenever I lapsed into French. What Ed didn’t realize, though, is that within two years, while my English didn’t improve very much, his deteriorated completely!

Within six months of my arrival, Ed Krebs and I started to work together on glycogen phosphorylase. He had been a student of the Cori’s in St. Louis. They believed that AMP had to serve some kind of co-factor function for that enzyme. In Geneva, on the other hand, we had purified potato phosphorylase for which there was no AMP requirement. Even though essentially no information existed at that time on the evolutionary relationship of proteins, we knew that enzymes, whatever their origin, used the same co-enzymes to catalyze identical reactions. It seemed unlikely, therefore, that muscle phosphorylase would require AMP as a co-factor but not potato phosphorylase. We decided to try to elucidate the role of this nucleotide in the phosphorylase reaction. Of course, we never found out what AMP was doing: that problem was solved 6-7 years later when Jacques Monod proposed his allosteric model for the regulation of enzymes. But what we stumbled on was another quite unexpected reaction: i.e. that muscle phosphorylase was regulated by phosphorylation-dephosphorylation. This is yet another example of what makes fundamental research so attractive: one knows where one takes off but one never knows where one will end up.

These were very exciting years when just about every experiment revealed something new and unexpected. At first we worked alone in a small, single laboratory with stone sinks. Experiments were planned the night before and carried out the next day. We worked so closely together that whenever one of us had to leave the laboratory in the middle of an experiment, the other would carry on without a word of explanation. Ed Krebs had a small group that continued his original work, determining the structure and function of DPNH-X, a derivative of NADH. I was still studying the alpha-amylases with Eric Stein. In collaboration with Bert Vallee, we were able to demonstrate that these enzymes were in reality calcium-containing metalloproteins.

In those days, we waited all year for the next Federation Meeting or Gordon Conference. It was an occasion for me to get together with my friends on the East Coast: Herb and Eva Sober and Chris and Flossie Anfinsen from NIH, Bill and Inge Harrington from Johns Hopkins, Bert and Kuggie Vallee from the Brigham and Al and Lee Meister, then at Tufts and later at Cornell, and many others. I have forgotten much about the meetings themselves. There was the excitement of hearing about the latest breakthroughs, the frantic preparations for talks that had to be given, and the numerous notebooks filled with information, questions and problems that had to be solved. I will never forget, though, the marvelous time we had together speaking far into the night about anything and everything. Some of these friends are gone today but their memory is still vivid.

I have two sons, François and Henri, from my first wife Nelly Gagnaux, a Swiss National who died in 1961. I married my present wife Beverley née Bullock from Eureka, California, in 1963. She has a daughter Paula from a first marriage. All three of our children are now married and my two sons each has a son.

I received the Werner Medal from the Swiss Chemical Society, the Lederle Medical Faculty Award; the Prix Jaubert from the University of Geneva and, jointly with Ed Krebs, the Senior Passano Award and the Steven C. Beering Award from Indiana University. I received Doctorates Honoris Causa from the University of Montpellier, France and the University of Basel, Switzerland and was elected to the American Academy of Arts and Sciences in 1972 and to the National Academy of Sciences in 1973.

This autobiography/biography was written at the time of the award and later published in the book series Les Prix Nobel/ Nobel Lectures/The Nobel Prizes. The information is sometimes updated with an addendum submitted by the Laureate.

Edmond H. Fischer died on 27 August 2021.

Nobel Prizes and laureates

Six prizes were awarded for achievements that have conferred the greatest benefit to humankind. The 14 laureates' work and discoveries range from quantum tunnelling to promoting democratic rights.

See them all presented here.