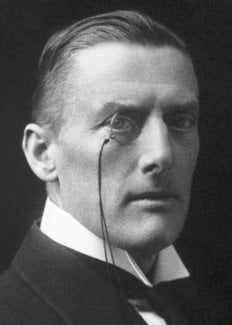

Sir Austen Chamberlain

Biographical

Sir Joseph Austen Chamberlain (October 16, 1863-March 17, 1937) was the eldest son of Joseph Chamberlain, the great British statesman known as the «Empire-builder» he was a half-brother of Neville Chamberlain, prime minister from 1937 to 1940. Like William Pitt the Younger, son of a famous father a hundred years earlier, he was trained for statesmanship. It was said of Austen that he did not choose a career, he accepted one. Having completed his boyhood schooling at Rugby and his university studies at Cambridge, he spent nine months at the École des Sciences Politiques in Paris and twelve months in Berlin. When he returned to Birmingham in 1887, he became, in effect, his father’s private secretary. Consequently, in 1892, when Austen Chamberlain was twenty-nine years old, he was well equipped to take a seat in the House of Commons, representing East Worcestershire, a constituency near the family home in Birmingham. Upon his father’s death in 1914, Austen became the member for West Birmingham, holding this seat until his own death in 1937.

Austen Chamberlain’s forty-five year career in the House of Commons may be divided into two periods: the first from his entry into the House in 1892 to 1922 when Lloyd George resigned as prime minister; and the second from 1922 to his death in 1937. In the first period he was concerned primarily with domestic questions; in the second, with international questions.

Chamberlain made his mark quickly. His maiden speech in 1893 was praised by William Gladstone; from 1895 to 1900 he was civil lord of the Admiralty; from 1900 to 1902, financial secretary to the Treasury; for one year, 1902-1903, the postmaster general; from 1903 to 1906, he was chancellor of the Exchequer.

In the wartime coalition government formed by Herbert Asquith in 1915, Chamberlain accepted the position of secretary of state for India, resigning in 1917. When David Lloyd George formed a coalition government after the election of 1918, he made Chamberlain his chancellor of the Exchequer. Chamberlain filled this post from 1919 to 1921 with distinction, paying the enormous debts accumulated during the war, maintaining a stable currency, and strengthening the national credit.

Upon Bonar Law’s retirement from the leadership of the Conservative Party in 1921, Chamberlain succeeded him for eighteen months. By this time Lloyd George’s coalition was tottering and the rank and file of the Conservative Party wanted to break away from it. When Chamberlain stood by the prime minister, the party, withdrawing from the coalition, first placed Bonar Law in the prime ministry and then Stanley Baldwin.

In the Baldwin government of 1924 to 1929, Chamberlain was secretary of state for foreign affairs. His brilliant tenure in office reflected the brilliant qualities he brought to it. In establishing policy, he was philosophically realistic and morally fearless; in pursuing a course of action he was patient, determined, resourceful; in personal negotiation he was linguistically fluent, faultlessly polite, charming in manner and elegant in appearance.

His first important act as foreign secretary shocked some diplomatic circles. In 1925 on behalf of his government he rejected the proposed Geneva Protocol in a speech to the Council of the League of Nations, not so much because it required compulsory arbitration of international disputes as because it was the Council which was to decide what action member states should take to enforce the authority of the League in time of crisis. He tempered the effect of this rejection by suggesting that the best way in theory to deal with situations as they arose was to «supplement the Covenant by making special arrangements in order to meet special needs».

The road to Locarno now lay open. Gustav Stresemann, the German foreign minister, and Aristide Briand, the French foreign minister, were willing to travel the road with him. After meticulous preparation during the summer of 1925, representatives of seven powers – Great Britain, Germany, France, Belgium, Italy, Poland, and Czechoslovakia – met at Locarno in southern Switzerland on October 5, 1925. On Chamberlain’s birthday, October 16, the foreign ministers initialed the documents known as the Locarno Agreements. Eight treaties or agreements in all, they included the Rhine Guarantee Pact (or «Locarno Pact») with Germany, Belgium, France, Great Britain, and Italy as signatories; individual treaties of arbitration between Germany and former enemy nations; guarantee treaties involving France, Poland, and Czechoslovakia; and a collective note on the entry of Germany into the League of Nations.

Upon his return to London after the triumph at Locarno, Chamberlain was given an immense ovation, was made Knight of the Garter, and a year later, along with Stresemann and Briand, his two companions in diplomacy, was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize.

In his later years in the foreign office Chamberlain dealt with vexing questions in China and Egypt. He displayed what firmness he could in defending British interests against encroachments of the Chinese Nationalists, but, lacking full cooperation from the United States and Japan, could forge no long-range solutions. To provide some permanent pattern for Anglo-Egyptian relations, Chamberlain drew up a draft of a treaty in 1927 which anticipated the treaty signed in the mid-thirties.

Out of office in his last years, partly because he chose to provide opportunity for the young men in Parliament, Chamberlain still spoke with a commanding voice in the Commons. He was among the first to see potential danger in Hitler; he favored both the imposition of sanctions against Italy during the Abyssinian crisis and their removal when they failed to prevent an Italian victory.

During these years he was also writing with a graceful pen. His Down the Years is part reminiscence, part character studies of great men he had known, part familiar essays. His Politics from Inside consists chiefly of letters he wrote to his stepmother from 1906 to 1914 to keep his ailing father informed of governmental and diplomatic events.

On March 17, 1937, Austen Chamberlain died of apoplexy, the same affliction that had killed his father a month before World War I began.

| Selected Bibliography |

| Chamberlain, Sir Austen, Down the Years. London, Cassell, 1935. Reminiscences, character sketches (including one of Briand and one of Stresemann). |

| Chamberlain, Sir Austen, The League of Nations. Glasgow, Jackson, Wiley, 1926. |

| Chamberlain, Sir Austen, Peace in Our Time: Addresses on Europe and the Empire. London, Allen, 1928. |

| Chamberlain, Sir Austen, Politics from Inside: An Epistolary Chronicle, 1906-1914. London, Cassell, 1936. A full account of political events written for his father after his illness in 1906. This book and Down the Years were translated and published in one volume: Englische Politik: Erinnerungen aus fünfzig Jahren. Übers. von Fritz Pick. Essen, Essener Verlagsanstalt, 1938. |

| Chamberlain, Sir Austen, Speeches on Germany. London, Friends of Europe Publications, 1933. |

| Coudurier de Chassaigne, Joseph Louis, Les Trois Chamberlain: Une Famille de grands parlementaires anglais. Paris, 1939. |

| Dictionary of National Biography. |

| Pensa, Henri, De Locarno au Pacte Kellogg: La Politique européenne sous le triumvirat Chamberlain-Briand-Stresemann, 1925-1929. Paris, 1930. |

| Petrie, Sir Charles A., The Chamberlain Tradition. New York, Stokes, 1938. |

| Petrie, Sir Charles A., The Life and Letters of the Right Hon. Sir Austen Chamberlain. 2 vols. London, Cassell, 1939. |

| Stern-Rubarth, Edgar, Three Men Tried: Austen Chamberlain, Stresemann, Briand and Their Fight for a New Europe. London, Duckworth, 1939. |

This autobiography/biography was written at the time of the award and first published in the book series Les Prix Nobel. It was later edited and republished in Nobel Lectures. To cite this document, always state the source as shown above.

The Nobel Foundation's copyright has expired.Nobel Prizes and laureates

Six prizes were awarded for achievements that have conferred the greatest benefit to humankind. The 14 laureates' work and discoveries range from quantum tunnelling to promoting democratic rights.

See them all presented here.