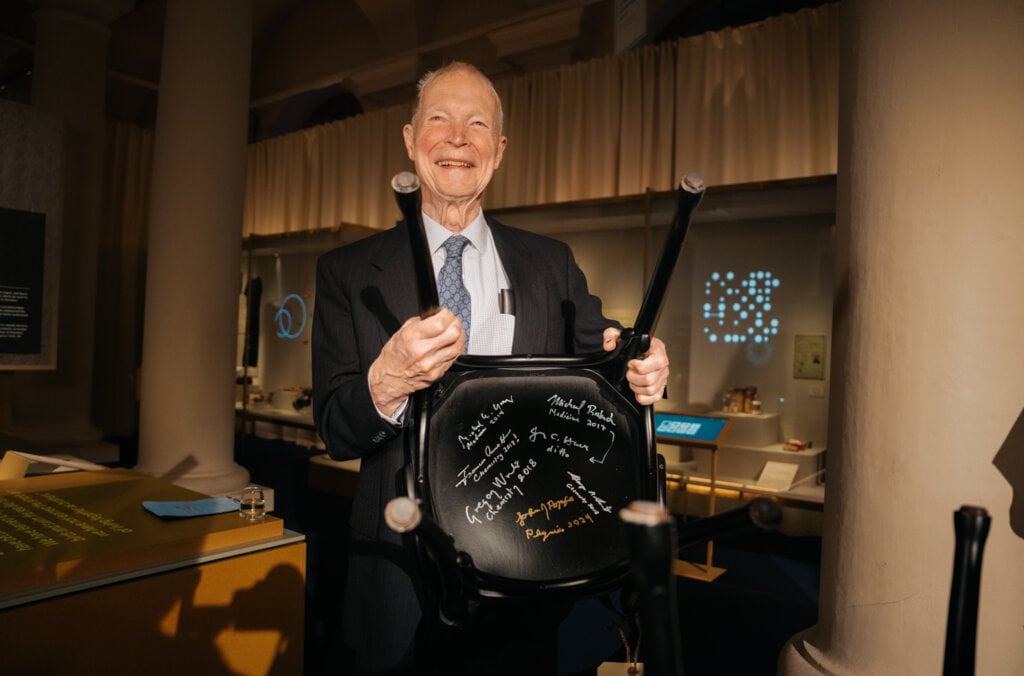

John J. Hopfield

Podcast

Nobel Prize Conversations

“I’ve never been part of the gang. I was a one man band playing little tunes.”

Meet physics laureate John Hopfield in a podcast recorded at his cottage in Selborne, England. Together with host Adam Smith, he reflects on the value of interdisciplinary work and how chemists and physicists might collaborate more closely.

They also discuss the future of AI and Hopfield’s greatest fears about it.

This conversation was published on 10 July, 2025. Podcast host Adam Smith is joined by Karin Svensson.

Below you find a transcript of the podcast interview. The transcript was created using speech recognition software. While it has been reviewed by human transcribers, it may contain errors.

MUSIC

John Hopfield: I’ve never been part of the gang. I was a one man band playing little tunes. Every once in a while somebody picked one up and found it was interesting, more often they picked it up and found it was not interesting.

Adam Smith: Those little tunes that John Hopfield refers to turned out to be extremely influential and were greatly magnified into great orchestral suites by many followers. In this conversation recorded in his cottage in Selborne, he talks about how he explored some of the rather more remote regions between fields. So many people feel he was a pioneer in so many areas and an early pioneer, especially of course in the field of AI where he developed the first neural network. It is with great pleasure that I invite you to join me to listen to this conversation with John Hopfield.

MUSIC

Karin Svensson: This is Nobel Prize Conversations and our guest is John Hopfield who received the 2024 Nobel Prize in Physics. He was awarded for foundational discoveries and inventions that enable machine learning with artificial neural networks and share the prize with Geoffrey Hinton. Your host is Adam Smith, Chief Scientific Officer at Nobel Prize Outreach. This podcast was produced in cooperation with Fundación Ramón Areces. John Hopfield is the Howard A. Pryor professor in the Life Sciences Emeritus and Professor of Molecular Biology Emeritus at Princeton University. Adam spoke to John Hopfield at his home in picturesque Selborne, England, where they discussed how interdisciplinary cooperation is the glue to build whole new fields when scouring neighbouring subjects yielded the perfect research problem and what scares him about his Nobel Prize awarded discovery. This time only we geek out on AI in a special discussion after the credits, so don’t miss it. But first, a few tips on what physicists can do when times are tough.

MUSIC

Smith: I wanted to start by asking you about your upbringing because your parents were physicists and you were brought up in a physics environment. I gather that that gave you a peculiar sense of the world through the lens of physics.

Hopfield: I would presume that it must have. Certainly I looked at my friends when I was a child. Their background was very different from mine. Mine was how does the world work? How do you find academic a job? I was born in -33. What was going on there at the time was the century of progress, the centennial of the city of Chicago, and there was a physics exposition. My father had been hired to set it up, set up the demonstration building as it were. This was deep in the depression. There were very few jobs. So a job which you wouldn’t otherwise thought of as being temporary was good enough at the moment for my father, it had to be. That’s how I wound up starting life in Chicago.

Smith: I see. With so much else to worry about it must have been a, in a way, a strange time to be focusing so much on physics and progress with the depression all around you.

Hopfield: Basically in 1930 there were no academic jobs that year period. Because universities always had young faculty and you paid them out of what money you had around. But the country was broke, so no universities were prospering. If you go forward and look at who was actually in the Los Alamos project, it was so heavy on Europeans because relative to the population, they came from a fairly steady academic income environment. There were more jobs per capita in Europe at the time, and the job base in science was per capita higher in the US so it was easy to get people, particularly on a threat of war, to come to the US at that point. If you look at what the president of Los Alamos in 1943, it’s strongly biased toward actually European scientists. That was a revolution. Ten years earlier Roosevelt came in and basically changed the economics of the country and in the long run it changed the job market and it’s very hard to see in this transient what’s going to be temporary, what’s the nature of the countries. But yes, it was an unusual time.

Smith: Was there ever any question that you were not going to be a physicist? Was it sort of expected of you and did you yourself feel that this was your path?

Hopfield: No, neither of them had come from science and it wouldn’t have been obvious I would to get from a child who a scientist in the US either. They simply didn’t push, but they didn’t push on a lot of things. They didn’t push on religion, for example, though I wound up with whatever I had and they had lived for about a year in Germany before I was born, in fact. But they were sort of European connected, but not as immigrants. It was what I had. They had always had the world around them as something that they could enthusiastically talk about.

Smith: So you grew up with enthusiasm or seeing enthusiasm for things and for knowledge for finding out?

Hopfield: Yes, I don’t think they would’ve understood the extent to which as the child grows, what you do reduces the environmental vacuum in which the child signs itself all directions possible.

MUSIC

Svensson: Hi Adam. John Hopfield was born in Chicago, but your conversation takes place in Selborne, a small town in the south of England. What kind of place is it?

Smith: It’s a beautiful place, beautiful and quiet. It’s nestled in rather sharp escarpments, wooded escarpments that form part of the south downs of England. It’s famous for having been the home of an 18th century parson called Gilbert White, who you may well have heard of. He wrote a book called ‘The Natural History of Cell Born’, which became very famous and detailed his close observation of all sorts of things in nature that a lot of people back in the 18th century felt were a bit irrelevant to look at like worms. His observational paths in particular I think were picked up on by people like Darwin later on as being important. Yes, it feels a bit stuck in time, a quiet English village.

Svensson: How did John Hop field end up there?

Smith: I believe it was his wife Mary Waltham’s home before they met. They kept it on and now they spend six months a year there and they spend the other half of the time in Princeton, which I guess you can do when you are in an emeritus professor.

Svensson: Sounds like a good life.

Smith: Yes, I think it is.

Svensson: Why was John Hopfield awarded the Nobel Prize?

Smith: He developed really this first neural network that has been the basis for so much all this machine learning. He was interested really in modeling how the brain works. He built a network of, if you like, artificial neurons with a feedback mechanism that could learn. That was the very beginning of people’s forays into modeling neural systems and building these learning networks. His network was called a Hopfield network and was the start of it all.

Svensson: He is a physicist, but his work is not confined to physics, is it?

Smith: No, not at all. He was trained as a physicist and he was in the physics department at Princeton in the 60s and 70s, but then also became part of the neuroscience department and the molecular biology department and really has used physics as a key to open up some of the mysteries of life. He explores all sorts of different aspects of the world.

Svensson: That seems quite intuitive but also quite unusual, isn’t it?

Smith: Many physicists have made the foray into life sciences, for instance. I think what he’s particularly good at is identifying just what the tools he has at his disposal allow him to ask and answer. For instance, he looked at a particular problem with hemoglobin called Alistair, and then he looked at electron transfer reactions and then he looked at neural networks. These are all problems that he could see that, what he had at his disposal allowed him to address interestingly. That’s all about the art of getting it right, having a big enough question and the tools to answer it.

Svensson: But why is it quite unusual then this kind of cross-disciplinary work?

Smith: I suppose one gets a bit confined in one’s rut. He might argue that there’s a tendency for people to move towards the sort of gravitational center of a field. If you’ve got the field of condensed metaphysics, you really want to be where the action is at in the middle of the field out at the periphery, you’re a bit alone. But that was his hunting territory. Places at the edge of things where interesting things were happening at the intersection between fields and maybe it’s riskier and also maybe your colleagues don’t recognise the achievement as much because it’s unknown territory, don’t quite know what you’ve done really that’s relevant to this field. Of course all scientists are probing the unknown, but are they probing the unknown that everyone’s expecting to be probed or are they going into places where few people dare to roam?

Svensson: So it’s not that biologists and physicists are sort of different species.

Smith: Wonder what Gilbert White would’ve said about that. I’ve often heard it said that, physics describes everything and so it is all physics essentially. Then the chemist might make the same claim and biologists might say they’re studying real complexity. I don’t know, I think the personality of scientists are so various that you really couldn’t draw any conclusions.

Svensson: How does he speak about this journey from physics to biology?

Smith: Well, I asked him about his transition from condensed metaphysics to neuroscience and let’s listen to what he said.

MUSIC

Hopfield: I worked in a particular narrow area very successfully and that area was running out of the kind of problems I knew how to solve. So I was at that point realising I had to find another source of problems because the good ones had been taken out, the small ones were small and you should work on the all problems. This was when I was roughly 35 and I was looking for a big problem. The area of physics I was associated with didn’t have anything appropriate that I could find. I went to the Nils Bohr Institute when they said they would run a seminar series on how does physics and biology get together and why don’t they get together? I had the wonderful position of being able to basically to pick the seminar speakers out of the best scientists available in Europe. They gave marvelous, interesting talks on their science. Nobody thought that the physicists would be of any help to them. This is true that of everybody, the physicists who might have done things weren’t exposed to the kind of biology that would’ve been much help. If you hear your thing about physics at the time is that if you asked the physicist what’s the biggest problem in biology, you might well have said the origin of life. Now, in many ways, that’s a wonderful answer. It’s true, but the time is not right. As I say, anybody who is going to seriously pursue that problem is starting in 1930 would get historically nowhere.

Smith: Exactly. The question is what actually is a good, big problem, not just a big problem.

Hopfield: I knew I had to be actively looking for a problem. I didn’t know how to do it. You had to be able to see that the problem was somehow related to things that I knew how to solve. That wasn’t a very big number. But when neurobiology, a neurobiologist came to talk, as did Nils Bohr, he would make it clear that his neurobiology had something to do with the ground problems of behaviour.

MUSIC

Smith: It seems to me that a lot of physicists let it lie with a sort of feeling that physics would solve it all eventually. But we don’t need to get involved yet. Let the biologists sort out some of the processes first and then then we can step in later. Is that fair?

Hopfield: There would’ve been many Hampshire who said not yet. It was never going to be the right time. The easy problems would be solved before very many in the community had waked up to the fact that you can take this physics over and drop it on a piece of science over here. There is some degree of mix of natural handshake because you need some mathematics actually to solve this problem over here. If you think about it for more than 10 seconds, you realise that most of what the neural system does is to solve problems that you write down traditional equations for. You may not know what the equation should be yet, but there was going to be equations of that structure and internal biology had to do with getting the signals in which start the system off and it computes for a while, gives you an answer. That process is computational. On the other hand, it’s dynamics. We want to know where the planets are next year. You see where they are now and you calculate using dynamics. So you see possibly there’s a connection between dynamical systems and understanding how neurobiology accurately processes this thing.

Smith: So you saw something like the question of associative memory and how it functioned as basically a calculation problem.

Hopfield: Yes. It was important that you saw the physics problem, that you saw the biology problem as the computational problem, that you knew that the computational stuff you already do some other edge of physics could be brought over and they look more like each other than you might have expected.

Smith: One of the things that you had the great insight to do was to take a problem, which is huge, but reduce it to something that you could get somewhere with. There have been many physicists who’ve attempted to tackle huge problems such as consciousness one thinks of Francis Crick or Donald Glaser, but those problems were just too big. You couldn’t get anywhere really.

Hopfield: Yes. They found that the problem how the nervous system generates motion. Motion is so complex, how many muscles do you have to drive to get and so on. People coming from biology, at least in the United States, had neglected mathematics ever since they were freshmen in college.

Smith: Yes. I suppose that is key, that dividing point makes a big difference.

Hopfield: Yes. You have to realise you don’t need all of the mathematics. The corners of mathematics, you better have them. Even with that basic idea, it took an act to put me in contact with a lot of good being done from different quarters on what looked to me like a common problem. I realised that even the people who were brought us in outlook just didn’t seem to have the tools themselves to work on the problem, which was the interesting problem, which is how the integration takes place. I say the interesting problem, you have to say it was a little naive. It’s a little luck.

Smith: Yes. It turned out to be a very interesting solution, which has spawned so much. It’s led to such enormous consequences. But given your success working in these interface areas, how do you encourage others to follow you? Because we still have a structure where physicists are physicists and biologists are biologists mainly and a few pioneers jump across and see what they can do. But is there more you can do than just wait for those pioneering individuals to make the links? Because it’s obviously very fertile territory if you can get it right.

Hopfield: I think it depends really only on the history of intellectual fields. We divide science up into chemistry, organic chemistry, physical chemistry, and with physics we do the same thing with physics labels. Every discipline keeps splitting itself as they get more knowledge within their discipline and they need some kind of contact with that larger piece of knowledge to work on the problems, which they’ve always to be getting bigger and more complex. There are pressures on the field to split and then to bring together those which are pretty close together anyway, to give yourself a little more intellectual base and into which you all are allowed can fit. You have to make space for them in your curriculum. Alright, these guys are marginal anyway, let’s push them off somewhere else. There’s the spontaneous inclination for large disciplines to split.

Smith: You have your put in many different Princeton departments, which you’ve helped build the neuroscience department, the molecular biology department, the physics department. So you span all of this. But for instance, with the teaching of neuroscience in colleges sometimes I always felt that it was full of possibilities and undergraduates coming through those courses felt they had a huge breadth of knowledge and it could see how to do many things, but they didn’t have any core discipline that they could bring to bear on the problems. They could see the connections, but they didn’t have the grounded center. I don’t know if that is how you see these things.

Hopfield: That was the problem. They were taught all about wood, but they never were told about glue with held things together and enabled you to do larger projects and understand some of the bigger issues which got you hooked. It’s a youngster.

Smith: People often talk about not seeing the wood for the trees, but in this case you’re seeing the wood but missing the glue.

MUSIC

Smith: What a beautiful place this is. It’s amazing the forested hill rising above.

Hopfield: Yes. And that’s the cell borne hanger.

Smith: Cell borne hanger.

Hopfield: Yeah. The geological formation of the south coast area is a series of ridges. They get higher higher and they get lower and lower ridge north inland and the hangers are dominated by beach and some kinds of oak. They were steep enough land that they weren’t suitable farmland for a long period of time. Pasture woodlands. But they were relatively undisturbed. It’s now what comprises a big part of the area of the South Cols National Park.

Smith: A lovely playground for young cell born resident to go exploring in now and back in the 18th century when Gilbert White was digging around in there.

Hopfield: The 18th century Gilbert White was still trying to find some of the basic behavioural questions of what do startlings do for the winter.

Smith: Yes. Having the observational powers to recognise that everything was interconnected. Even the small and despicable worm had a role to play.

Hopfield: Yes. What a wonderful discovery that was. Some people might divide science world into lumpers and splitters. The lumpers are all for putting the observed categories, putting them together in different ways. They’re a smaller number of things. Now they understand the structure of what the lumps should be. The splitters on the other hand say, look at this characteristic of the things that you say are lumps, they’re not lumps at all. Physics has far more glitters than many of the subsidies. There was a dividing line somewhere between is matter made up of atoms or is matter a continuous stol and your atoms are a whimsical creation of the particular way you did experiments.

Smith: That’s a nice question.

MUSIC

Smith: I wanted to ask you also about the consequences of that early work which have turned into machine learning and are dominating so much of what we have around us and promise to be more influential still. I suppose the question that everybody wants to know is what are your fears about it? There are many ways to think about that. It can be just the fears of the implementation of machine learning AI to replace things that humans are used to doing and feel that they don’t want to let go of. It can be doomsday scenarios of AI becoming conscious or already being conscious if you were talked to Geoffrey Hinton taking control where it’s not supposed to take control. Where do your fears lie if you have any?

Hopfield: The thing that bothers me most about AI is the inability of those people who work in the field to tell you why it works. There are enough things that you can do with it, which are extremely disruptive because you don’t know how far these things can be done intellectually or what might be done viciously. If you have no limits on what might happen, the idea that you should then advertise and sell this stuff as a viable product in a civilised world, if the product didn’t have its flaws, it wouldn’t be such an issue. But little like doing medicine, when you have a process which makes new medicines for you and see it works 70% of the time, and if one of those doesn’t work, suddenly it could wipe everything out. If you had a product which might make a chain reaction and destroy all of whatever was supposed to be good for. If you had that possibility, you’d worry.

Smith: It certainly forms the basis of sci-fi scenarios that where somebody creates something that has some cataclysmic effect unintended. Sort of Kurt Vonnegut scenario or something like that.

Hopfield: Yes, in 1973 the basis for modern genetic engineering was discovered and there was a lot of discussion in all biology departments of a variety of different flavours about whether this was something which was safe or whether it was so unsafe that you really had to tightly regulate laboratories, which you’re going to try to do it. There was active debate in major biology departments about how much recombinant DNA technology should be going on in universities. This is the kind of discussion which there ought to be in the AI world and you just do not see it going on.

Smith: So why is that? Because that, that example of the way that people talked about the potential of the genetic revolution in the seventies is held up as a paragon of how you should do things, the assima conferences etc. There if you liked the understanding of what was happening was greater than is true for AI now. Why are we left in this situation where the conversation isn’t happening to such an extent?

Hopfield: There are a lot of things pushing. One is the very large amounts of money, which can be rapidly made by ignoring regulation. People knew that there were all kinds of things you’d like to try in recombinant DNA. Nobody had much of any idea of how many of those things were real, how many could you actually do or was this a nice in principle thing. But the cost of doing one experiment just exhaust a university and AI is peculiar in the sense that its materials caused are very small and it suffers from all the things that people worried about in becoming in DNA. But the AI had the advantage that there was no long series of steps that you had to do to get the whole thing working, to make one operation on one child succeed. I can’t think of another case really involving physics where the same worry though there must have been a same, there must have been physically experiments with people of particular religion might believe that God would strike down so on if the experiment were done. That set of people never won in the physics. That you didn’t have a set of people who was going to be out of their livelihood if they didn’t win the battle of is dysregulated or not.

MUSIC

Smith: I wanted to ask what it’s like receiving the Nobel Prize. You’re sort of retired but must be very hard to retire when so many people want your attention. What’s it like adding yet another award to your collection of awards and having yet more attention at this age?

Hopfield: I’ve never been part of the gang. I was a one man band playing little tunes every once in a while. Somebody picked one up and found it was interesting more often than they picked it up and found it was not interesting.

Smith: Thank you very much indeed. What a pleasure to come down here and meet you.

Hopfield: Do you know where you’re going here locally?

Smith: I do, yes. I’m fine. Thank you very much.

Svensson: You just heard Nobel Prize Conversations. If you’d like to learn more about John Hopfield, you can go to nobelprize.org where you’ll find a wealth of information about the prizes and the people behind the discoveries. Nobel Prize Conversations is a podcast series with Adam Smith, a co-production of Filt and Nobel Prize Outreach. The producer for this episode was me, Karin Svensson. The editorial team also includes Andrew Hart and Olivia Lundqvist. Music by Epidemic Sound. If you’d like to hear from another researcher who mined gold between established scientific disciplines, check out our earlier episode with 2019 physics laureate Didier Queloz. You can find previous seasons and conversations on Acast or wherever you listen to podcasts. Thanks for listening.

MUSIC

Svensson: Adam, I really wanted this to fit into the episode, but it was just a bit too far off to the side.

Smith: While it is a bit speculative, bit abstract, exploratory if you like, but I think you’re right. I think it’s worth including we’ve never done that before. We’ve never bolted on an extra piece. But I think in this case you’re right. Although it doesn’t fit neatly into the rest of the conversation, it does matter.

Svensson: Okay. Then give us some setup on what we’re about to hear.

Smith: On first listen it might sound like it’s just a technical back and forth about AI neural networks, the brain, but really he’s discussing the limits of artificial intelligence, what current models of artificial intelligence might deliver. The big question of how much we can do with artificial intelligence without understanding more about biology

Svensson: Why is this so important?

Smith: I suppose he’s challenging the kind of popular narrative that we just need bigger AI models to solve everything. He’s reminding us that complexity, the kind of messy complexity of biology, gives us something that machines perhaps can never give us. We have to incorporate some of that messiness into our models if we’re ever going to be able to get machines to think like we do if that’s what we want them to do.

Svensson: Alright. Any other key points to look at for?

Smith: Yes, it’s interesting to listen to how Hopfield talks about the fact that things change with scale. That just adding more neurons or more nodes or more complexity doesn’t necessarily get you to just more of the same but can change things that you get new physics arising from differently sized systems or you should expect perhaps new physics to arise in different systems. That’s one of his arguments about the brain, that you cannot possibly understand the brain by understanding small scale neural systems. Even if you understand all the biology because something new is going to arise when it gets much bigger and much more complicated. Making it bigger will perhaps confound your understanding and new physics will pop up and he has demonstrated that and believes that that is really what we should be on the lookout for.

Svensson: Okay. Here it is an epilogue of sorts to this episode with John Hopfield.

Smith: One of the things that your work has shown or rather help make more apparent is that it’s very hard to predict how a system will behave as it gets bigger, as it gets more complex.

Hopfield: Most problems in physics and math have bridges by saying that there’s some measure along the mathematical line and there’s a transition to. Where that transition is dependent on what problems you have, but that’s just a coefficient. If it’s just a coefficient in any particular problem, you can ultimately figure out what’s going on. That problem can’t have been non-regular because you can’t find that out. But if going on from there you go.

Smith: Then let me finish with a question that follows on from that perhaps, which is, do you think that the coefficients will be found for the brain? Do you think we’ll be able to sort out in the end how it works? Which was the broadly the question that brought you into the computing field?

Hopfield: I think we’re going to see ever bigger biology is very complex, it will reduce biology to these two variables and solve the rest of it in some average way. Then that doesn’t work to solve all the problems you’d like to solve. You’re doing perception, it works for two years with one frequency or what have you, and somebody comes along and that, oh, but I can make a six neuron system and they can and down can solve all the problems. Well, not all, there’s a certain fraction that you can’t get, but there’s always this fracture that you can’t get and progress will be seen and there’ll be a step. The AI types of these, we’ve learned all these you needed to tell us about biology. We really are tired of hearing biology lectures. They will take their things off and their toys and play with them and they’ll get the toys will polish them really much better than when they were handed the toys. But they don’t solve all the problems. There’s another problem. Then there’s a set of problems. Let’s see. I think there’s a series of revolutions which actually goes on. One of the first big resolutions was discoveries would’ve been that you could take a one neuron system feed back on itself and make a two state system. How many different neurotransmitters do you need to have to make such a system go? One neuron doesn’t have much computing power. Minsky proves that for the perceptron wrote a whole book really driving the mathematical theory of the perceptron and why the inadequate description of computation. If you have layers of cells, the perception is one layer, one cell. You say, I know how to beat that. The multiple neuron, multiple cell problem can’t be solved if you don’t do something additional about it. If you take one neuron, one cell solves the problems, two neurons, four cells maybe solves a fourth problem. But it’s finite. You keep pushing it out but that’s all you could do. Every time you push something out, you’ll say, well, let’s have more cells. Biology has more cells. But if you make cells that simple, you don’t have as many possibilities is if you make them more complicated like their biological ones. So when these trade offs cells will get more biological, there will be more of them. It’ll take more data to set all those parameters to the system. Then you could never actually do this beyond such a point if biology didn’t have this additional thing. There is a model in which step by step you include more and more biology and always stick to something which you know you could make biologically. I think that would be a very hard road push very far.

Smith: It needs somebody to come along with some theoretical revelation. Modeling will get you so far and as you say, you can improve the biological integrity of your model system. But it would be a very long road. There are perhaps that many people working on theory of neuroscience. I don’t know.

Hopfield: What you say is I think true in all corners except for the question of computation and quantum mechanics.

Smith: Yes. There it is.

Hopfield: There are an astonishingly large number of different quantum systems. People are playing with hoping that they have the holy grail for moving forward. I think that’s the unknown.

Nobel Prize Conversations is produced in cooperation with Fundación Ramón Areces.

Nobel Prizes and laureates

Six prizes were awarded for achievements that have conferred the greatest benefit to humankind. The 14 laureates' work and discoveries range from quantum tunnelling to promoting democratic rights.

See them all presented here.