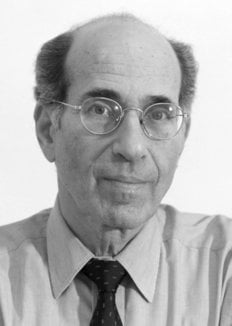

Richard Axel – Curriculum Vitae

| Richard Axel, born July 2, 1946, New York, NY, USA | |

| Address: | Howard Hughes Medical Institute, Columbia University, Hammer Health Sciences Center, 701 West 168th Street, Room 1014, New York, NY 10032, USA |

| Academic Education and Appointments | |

| 1967 | A.B. Columbia University, New York, NY |

| 1970 | M.D. Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Baltimore, MD |

| 1978 | Professor, Pathology and Biochemistry, Columbia University |

| 1984- | Investigator, Howard Hughes Medical Institute, Columbia University |

| 1999- | University Professor, Columbia University |

| Selected Honours and Awards | |

| 1969 | The Johns Hopkins Medical Society Research Award |

| 1983 | The Eli Lilly Award |

| 1983 | Member, the National Academy of Sciences |

| 1983 | Member, the American Academy of Arts and Sciences |

| 1984 | The New York Academy of Sciences Award in Biological and Medical Sciences |

| 1989 | The Richard Lounsbery Award, National Academy of Sciences |

| 1996 | The Unilever Science Award, with Dr. Linda Buck |

| 1997 | New York City Mayor’s Award for Excellence in Science and Technology |

| 1998 | Bristol-Myers Squibb Award for Distinguished Achievement in Neuroscience Research |

| 1999 | The Alexander Hamilton Award, Columbia University |

| 2001 | NY Academy of Medicine Medal for Distinguished Contributions in Biomedical Sciences |

| 2003 | The Gairdner Foundation International Award for Achievement in Neuroscience |

| 2003 | The Perl/UNC Neuroscience Prize, with Dr. Linda Buck |

| 2003 | Member, the American Philosophical Society |

The Nobel Assembly at Karolinska Institutet

Richard Axel – Nobel Lecture

Lecture Slides

Pdf 7.19 MB

Read the Nobel Lecture

Pdf 1.38 MB

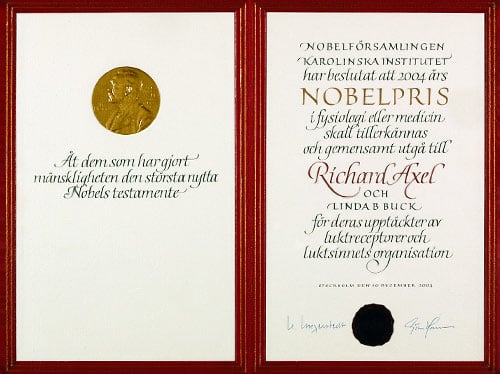

Richard Axel – Nobel diploma

Copyright © The Nobel Foundation 2004

Calligrapher: Susan Duvnäs

Richard Axel – Banquet speech

Richard Axel’s speech at the Nobel Banquet in the Stockholm City Hall, December 10, 2004.

Your Majesties, Your Royal Highnesses, Your Excellencies, honored guests, ladies and gentlemen.

Émile Zola asked in an address to students, “Did science promise happiness? No, I don’t think so,” he replied. “It promised truth and the question is whether truth will ever make us happy.” Last month, science afforded me enormous happiness.

This evening Linda Buck and I received a medal which is inscribed with three words, Creavit et promovit. He created and he promoted. The words do not honor us. They honor the vision of Alfred Nobel, the Nobel Prize that importantly encourages the freedom to acquire knowledge. This freedom cannot be taken lightly. Both myth and history reveal the conflict between intellect and power. With the tasting of the fruit of the Tree of Knowledge of Good and Evil and the expulsion of Adam and Eve from the garden, with Prometheus’ deliverance of fire to mankind and the opening of Pandora’s Box, we observe man’s intellectual curiosity punished by suffering. Ironically, it is this intellectual creativity that allows man to overcome his punishment, his suffering, to allow man to prevail. Indeed, the advancement of knowledge is too often perceived as transgression.

The conflict between intellect and political and religious authority will intensify as we continue to address questions concerning the origin of man, the nature of our genes, and how they define our biological character and most elusively, the relation between genes and behavior, emotion, and cognition. This knowledge too often elicits discord and even fear. This fear has led to the disturbing notion that there is knowledge best left unknown. This thinking undermines the scientific process. We must choose either to have science or not to have it, and if you have it you cannot dictate the kinds of knowledge that will emerge and this knowledge will inevitably have the potential for both good and evil. With this knowledge, our lives and those of our descendants will be inexorably changed and it is our shared responsibility to assure that this change is for the better. As we read in “The Ascent of Man,” “It is not within the business of science to inherit the earth, but to improve it.”

Tonight I speak for Linda and myself in thanking all of you for this honor and this spectacular celebration. This award is made not to me as a man, but for my science and for me science is a joyous obsession. Linda Buck and I have combined molecular genetics with neuroscience to approach the previously tenuous relationship between genes, perception and behavior. We have asked how the brain builds an internal representation of the external sensory world and how the recognition of olfactory stimuli might lead to meaningful thoughts and behaviors. While performing these experiments, in watching the data unfold remarkably before our eyes, it seemed inconceivable that we could experience a moment of greater joy or fulfillment. But tonight we stand with you, with Their Majesties The King and The Queen, with fellow scientists, with honored guests and friends, amidst the lights, the music, the trumpets, the wine and feel an affection that adds a new and very human dimension to our science. In the midst of this joy of these festivities, I raise my glass to celebrate you. Skål!

Copyright © The Nobel Foundation 2004

Richard Axel – Photo gallery

Richard Axel receiving his Nobel Prize from His Majesty the King Carl XVI Gustaf of Sweden at the Stockholm Concert Hall, 10 December 2004.

Copyright © The Nobel Foundation 2004

At the Nobel Prize Award Ceremony at the Stockholm

Concert Hall. Economics Laureates Finn Kydland (right) with Richard Axel (left) who shared the 2004 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine with Linda B. Buck (middle).

Copyright © Pressens Bild AB 2004, S-112

88 Stockholm, Sweden, telephone: +46 (0)8 738 38 00

Photo: Henrik Montgomery

Richard Axel delivering his banquet speech. © Nobel Media AB 2004. Photo: Hans Mehlin

Photo: Hans Mehlin

Richard Axel – Documentary

A short documentary about the lives and work of the 2004 Nobel Laureates in Physiology or Medicine Richard Axel and Linda B. Buck, and their research on the olfactory system.

Richard Axel – Prize presentation

Watch a video clip of the 2004 Nobel Laureate in Physiology or Medicine, Richard Axel, receiving his Nobel Prize medal and diploma during the Nobel Prize Award Ceremony at the Concert Hall in Stockholm, Sweden, on 10 December 2004.

Richard Axel – Other resources

Links to other sites

Dr. Richard Axel’s page at Howard Hughes Medical Institute

Richard Axel – Interview

Interview with the 2004 Nobel Laureates in Physiology or Medicine, Richard Axel and Linda B. Buck, by science writer Peter Sylwan 11 December 2004.

The Laureates talk about the big event of the Nobel Prize Award Ceremony; the genes of the olfactory system (1:47); the importance of the sensor organ (3:33); the smell of emotions (10:28); the mapping out of the molecules of sense inside the brain (14:43); and challenges for neuroscience in the future (18:29).

Participating in the 2004 edition of Nobel Minds: the Nobel Laureates in Physics, David J. Gross and Frank Wilczek, the Nobel Laureates in Chemistry, Aaron Ciechanover, Avram Hershko and Irwin Rose, the Nobel Laureates in Physiology or Medicine, Richard Axel and Linda B. Buck and the Laureates in Economic Sciences, Finn E. Kydland and Edward C. Prescott. Program host is Nik Gowing.

Telephone interview with Dr. Richard Axel after the announcement of the 2004 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine by science writer Joanna Rose, 4 October 2004.

Interview transcript

– Hello.

– Hello, is this Richard Axel?

– Yes, it is.

– Hello. My name is Joanna Rose. I am calling from Nobelprize.org, which is the official web site of the Nobel Foundation. May I ask you some questions and congratulate to the Prize?

– Yes, I am still a bit shocked …

– You are?

– … and quite surprised and deeply honoured …

– I understand. You didn’t expect the message tonight?

– No, I did not, and I am in California, and received a phone call from my assistant in New York.

– I understand. So did you just go to sleep?

– I just woke up, three o’clock in the morning.

– What was your first reaction when you heard about the Prize?

– My first reaction was one of surprise, and then that was coupled with joy, and I am really very, very pleased that this work was recognised by so … meaningful a group of people in the world. I think it’s a Prize that reflects not my effort alone, but the efforts of a very large group of students and fellows in my laboratory, working with intensity and excitement on a problem.

– What do you think it will mean for your work now, or for you personally?

– I think that it is important to feel that one’s work is viewed by the rest of the world as having a significance and it will hopefully intensify my efforts.

– I understand also that this is going to be a very long day for you. What are you going to do, do you think?

– First I am going to have a cup of coffee.

– You had no time yet?

– No

– OK.

– And then I am going to hug my girlfriend and talk with my family and laboratory. I have not yet heard from the Nobel Committee …

– Oh, I see. Do you think this will influence somehow your future work?

– Oh, it can’t help but not influence your work, because it puts your work in the public arena. But I would hope that whatever values and intensity and excitement I brought to my work will just be enhanced by this recognition.

– I understand that the discovery that you got now the Prize for was made in 1991, and I wonder, was this a surprise for you, then?

– In 1991? Yes, in 1991 we, Linda Buck and I, Linda was a fellow in my laboratory, had been searching for the … that recognised odorous … in the environment, and what Linda was able to demonstrate in a very elegant series of experiments, was that perhaps as much as three or five percent of the genes in the genome were dedicated to this function. So fifteen hundred genes were dedicated to this function, which was a surprise but also gave a significant insight into the process of this perceptual system. So the discovery of all of these genes, including receptors, was a surprise and receiving the Nobel Prize for it was also a surprise.

– Life is full of surprises.

– Life is full of good surprises.

– As I understand you are working in two different laboratories now, are you competitors?

– I would say not. We are interested in similar general problems, but take different approaches to those problems, and so we don’t directly compete now. I have emphasized olfaction in two different systems – one, mammals and the second system that’s been fascinating for us is insects. Linda’s work largely involved mammals, and so I don’t think … I don’t feel competitive at all with Linda, and I am trying not to engage in experiments that elicit competition between former student s and fellows in my lab.

– You mentioned that there is a large group of people that are involved. What would be a message from you to students now, whose greatest wish is maybe to win a Nobel Prize, to make a discovery?

– I think the important message, if I were to talk with students, is that the joy of science is in the process, and not in the end. That science is not a move to an end, rather it is a process of discovery, which onto itself should be a meaningful pleasure.

– Before I thank you, I have just a last question: Have you ever visited the Nobel web site, the official one?

– Yes, I have. Should I visit it now?

– Maybe. Then you’ll be convinced about your Prize.

– I have visited it to read William Faulkner’s Nobel acceptance speech.

– Thank you very much, and please have a nice day today.

– Thank you very much. Bye bye.

Did you find any typos in this text? We would appreciate your assistance in identifying any errors and to let us know. Thank you for taking the time to report the errors by sending us an e-mail.

Richard Axel – Biographical

New York City is my world. I was born in Brooklyn, the first child of immigrant parents whose education was disrupted by the Nazi invasion of Poland. Although not themselves learned, my parents shared a deep respect for learning. I grew up in a home rich in warmth, but empty of books, art or music. My early life and education were centered on the streets of Brooklyn. Stickball, baseball with a pink ball and broom handle, and schoolyard basketball were my culture. In stickball, a ball hit the distance to one manhole cover was a single, and four manhole covers, a home run, a Nobel Prize. My father was a tailor. My mother, although quick and incisive, did not direct her mind to intellectual pursuits and I had not even the remotest thought of a career in academia. I was happy on the courts. In those days, we worked at a relatively young age. At eleven, I was a messenger, delivering false teeth to dentists. At twelve, I was laying carpets, and at thirteen, I was serving corned beef and pastrami in a local delicatessen. Vladimir, the Russian chef, was the first to expose me to Shakespeare which he recited as we sliced cabbage heads for coleslaw.

My local high school had the best basketball team in Brooklyn but the Principal of my grade school had a vision different from my own and insisted that I attend Stuyvesant High School, far away in Manhattan. Stuyvesant High advertised itself as a school for intellectually gifted boys but had the worst basketball team in the city. I was unhappy about the prospect of attending for it seemed antithetical to my self-image. Shortly after I entered, however, my world changed. I embraced the culture and aesthetics of Manhattan. The world of art, books and music opened before me and I devoured it. In school, I heard bits of an opera for the first time. I remember it distinctly, the Letter Duet from Mozart’s Marriage of Figaro. The next night I attended Tannhäuser at the Metropolitan Opera and thus began a love affair, bordering on an obsession, that has had no end. Twice a week, I stood on line for standing room tickets at the Metropolitan Opera where I was exposed to a cult of similarly obsessed but far more knowledgeable afficionados who taught me the intricate nuances of this rich genre. The great Italian tenor, Franco Corelli, would serve us coffee as we waited and the diva, Joan Sutherland, would invite us backstage.

On other days, I would read in a most beautifully appointed place, the Reading Room of the Central New York Public Library on 42nd Street. One passes the pair of sculpted lions, ascends a flight of stairs into a huge high-ceilinged room of impressive silence where I read incessantly without direction but with a newfound fascination that made up for years of illiteracy. I met a coterie of library dwellers, men and women of New York, who spent all of their days in the Reading Room. I did not know who they were or how they came to be there, but they had an insight and understanding of literature that amazed and still perplexes me and they were my teachers. This was New York for me, a city of the culturally obsessed that opened up before me and framed my new world.

To support a seemingly extravagant life for a young high school student, I worked. I used my skills as a waiter in a delicatessen in Brooklyn, to wait tables in the cafes and nightspots of Greenwich Village. In the sixties, the Village was the home of the beat generation that through music and poetry and ultimately protest translated discord into meaningful changes in both America and the world. Stuyvesant High School was on the fringe of Greenwich Village and some of its teachers were artists, writers, performers who fueled the politically-fired student body, many the sons of Marxist immigrants. With this array of artistic faculty Stuyvesant nourished my new and voracious appetite.

But old worlds die hard. I continued to play basketball in high school and this led to a most memorable and humbling experience. I came onto the court as the starting center, and the center on the opposing team from Power Memorial High School lumbered out on the court, a lanky 7 foot 2 inch sixteen year old. When I was first passed the ball, he put his hands in front of my face, looked at me and asked, “What are you going to do, Einstein?” I did rather little. He scored 54 points and I scored two. He was the young Lew Alcindor, later known as Karim Abdul Jabar, who went on to be among the greatest basketball legends and I became a neurobiologist.

My decision to remain in New York and attend Columbia College revealed the provincial but endearing quality of my family. When I chose to accept a gracious scholarship offered by Columbia, my father was disappointed. It was a fact well known that the brightest children of Brooklyn immigrants attended City College. My freshman year at Columbia, I lived with abandon. The opera, the arts, the freedom, the protest left little time for study. In the first semester, I met a student from Tennessee, Kevin Brownlee, who remains a dear friend and is now a Professor of Medieval French at the University of Pennsylvania. Brownlee urged me to redirect this intensity to learning. The world of the arts will remain, but my time at Columbia University was limited. Once again, a new world opened before me. With Kevin as my guide, I became a dedicated, even obsessed, student. My life was spent in a small room lined with volumes of Keats’ poetry at the Columbia Library and I immersed myself in my studies. The study of literature at Columbia in the sixties was exciting in the presence of the poet, Kenneth Koch, the critics, Lionel Trilling, Moses Hadas, and Jacques Barzun. It was largely chance, however, that led me to biology.

To support myself in college, I obtained a job washing glassware in the laboratory of Bernard Weinstein, a Professor of Medicine at Columbia University. Bernie was working on the universality of the genetic code. The early sixties was a time shortly after the elucidation of the structure of DNA and the realization that DNA is the repository of all information and from which all information flows. The genetic code had just been deciphered and the central dogma was complete. I was fascinated by the new molecular biology with its enormous explanatory power. I was a terrible glassware washer because I was far more interested in experiments than dirty flasks. I was fired and was rehired as a Research Assistant and Bernie spent endless hours patiently teaching this scientifically naïve, but intensely interested young student. I was torn between literature and science. Dubious about my literary ambitions and fascinated by molecular biology, I decided to attend graduate school in genetics.

My plans were thwarted by an unfortunate war and to assure deferment from the military, I found myself a misplaced medical student at Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine. I entered medical school by default. I was a terrible medical student, pained by constant exposure to the suffering of the ill and thwarted in my desire to do experiments. My clinical incompetence was immediately recognized by the faculty and deans. I could rarely, if ever, hear a heart murmur, never saw the retina, my glasses fell into an abdominal incision and finally, I sewed a surgeon’s finger to a patient upon suturing an incision. It was during this period of incompetence and disinterest that I met another extremely close friend, Frederick Kass, now a Professor of Psychiatry at Columbia University. Fred was an unusual medical student, a Texan with a degree in art history from Harvard, who remains a kindred spirit.

It was a difficult time, but I was both nurtured and protected by Howard Dintzis, Victor McCusick, and Julie Krevins, three professors at Johns Hopkins who somehow saw and respected my conflict. Without them, there is little question that I would not have been tolerated but they urged the deans to come up with a solution. I was allowed to graduate medical school early with an M.D. if I promised never to practice medicine on live patients. I returned to Columbia as an intern in Pathology where I kept this promise by performing autopsies. After a year in Pathology, I was asked by Don King, the Chairman of Pathology, never to practice on dead patients.

Finally, I was afforded the opportunity to pursue molecular biology in earnest. I joined the laboratory of Sol Spiegelman in the Department of Genetics at Columbia University. Spiegelman was a short, incisive, witty man with a tongue as sharp as his mind. Spiegelman was the first to synthesize infectious RNA in vitro and this led to a series of extremely interesting and clever experiments revealing Darwinian selection at the level of molecules in a test tube. Sol recognized the importance of the early RNA world in the evolution of life and had recently turned his laboratory to a study of RNA tumor viruses. An immediate bond formed between us and Sol taught me how to think about science, to identify important problems, and how to effect their solution.

Although I felt a growing confidence in my abilities in molecular biology, I was naïve in other areas of biology, notably biophysics. Importantly, I had a sense early in my career that my interest in biology was eclectic and that I would need a concomitantly broad background to embrace the different areas of biology without trepidation. I left to begin a second postdoctoral fellowship at the National Institutes of Health, working with Gary Felsenfeld on DNA and chromatin structure. Since I entered medical school to avoid the draft, I had a military obligation that was fulfilled by my years at the NIH and was endearingly termed a “yellow beret.” Gary was great, but the NIH was alien, a government reservation with a fixed workday. As a night person, I found it strange and at some level difficult since I arrived at noon after all the parking spaces were occupied, left at midnight and accumulated an increasing number of parking tickets. In the midst of a molecular hybridization reaction, I was arrested by two FBI agents (the NIH is a federal reservation) for 100 summonses for parking violations.

As a fellow in Felsenfeld’s lab studying how chromatin serves to regulate gene expression, I formed close friendships that continue to the present. On the beach at Cold Spring Harbor, I sat with Tom Maniatis and Harold Weintraub and talked about chromosome replication and gene expression and within a few hours a bond formed, a respect for one another and for one another’s thinking, that has lasted for thirty years. Hal, unfortunately, died ten years ago of a brain tumor, but his warmth, his creativity persist.

Sol Spiegelman invited me to return to Columbia as an Assistant Professor in 1974 in the Institute of Cancer Research. I was ecstatic to occupy a lab and office adjacent to his. Sol had many visitors in those years, and when he felt bored in a meeting he would excuse himself and hide in my office where we talked science until his visitors finally gave up and left. I was studying the structure of genes in chromatin and had the good fortune of participating in a revolution made possible by recombinant DNA technology. I spent a great deal of time with Tom Maniatis, who pioneered many of the techniques in recombinant DNA. Tom left Harvard for Cal Tech, because he was restricted from performing recombinant DNA experiments in Cambridge, Massachusetts. We learned how to cut and paste DNA, to isolate genes and to analyze their anatomy down to the last detail. We recognized that to understand gene control and gene function, however, required a functional assay. Within months of establishing my own laboratory in 1974, Michael Wigler, my first graduate student along with Sol Silverstein, a Professor at Columbia, developed novel procedures that allowed DNA-mediated transformation of mammalian cells. Michael, even at this very early stage in his career, was conceptually and technically masterful and within a few years he devised procedures that permitted the introduction of virtually any gene into any cell in culture. He developed a system that not only allowed for the isolation of genes, but also for detailed analysis of how they worked. We now had a facile assay to study the sequences regulating gene expression as well as gene function.

Michael went off to the Cold Spring Harbor Laboratories and simultaneous with Bob Weinberg at MIT identified the mutant ras gene as the gene responsible for malignant transformation in many cancer cells. My laboratory went off in many directions, first identifying the regulatory sequences responsible for control of specific gene expression. At the same time, a fellow, Dan Littman, now a Professor at NYU, joined the lab interested in two molecules that characterize the major classes of T cells. Dan, along with a student, Paul Maddon, succeeded in exploiting the gene transfer to isolate these two molecules. As often in science, serendipity heightened the interest in these molecules: we demonstrated that one of these receptors, CD4, was the high affinity receptor for HIV, allowing attachment and infection of immune cells.

This early work on recombinant DNA was a period of enormous excitement, for it led to a revolution in both thinking and technology in biology. It provided a new tool for the study of fundamental problems and spurred a new and valuable industry, biotechnology. We, who were involved at its inception, were perhaps a bit haughty, aggressive and proud, and were accused by many of playing “God.” As evidence, the press noted that “I baptized my first child, Adam.”

Recombinant DNA aroused a good deal of passion and hostility. The notion of tinkering with life was thought to endanger life and this cry became one of the major indictments of modern biology. These experiments raised endless debate because the idea that genes can be taken out of one organism and introduced into the chromosome of another is by itself upsetting. The very notion of the performance of recombinant DNA was linked with the mysterious and supernatural. This conjured up myths that elicited intense anxiety. Recombinant DNA, it was feared, would permit biologists to alter individual species as well as the evolution of species. This controversy emphasized the fact that advances in science may indeed bring harm as well as benefit. In the case of recombinant DNA, as François Jacob said, “Apocalypse was predicted but nothing happened.” In fact, with recombinant DNA, only good things happened. At a practical level, the ability to construct bacteria replicating eucaryotic genes has allowed for the production of an increasingly large number of clinically important proteins. At a conceptual level, gene cloning has permitted a detailed look at the molecular anatomy of individual genes and from a precise analysis of these genes we have deduced the informational potential of the gene and the way in which it dictates the properties of an organism.

At a personal level, the emergence of a new discipline, biotechnology, introduced me to a world outside of academia. This important excursion showed me that brilliance is not limited to universities. I met and remain very close to two dynamic leaders of technology development, Fred Adler and Joe Pagano. Despite disparate histories, we remain very close and they continue to fascinate me with lives quite different from that of a university professor.

In 1982, I began to think about the potential impact of the new molecular biology and recombinant DNA technology on problems in neuroscience. Molecular biology was invented to solve fundamental problems in genetics at a molecular level. With the demystification of the brain, with the realization that the mind emerges from the brain and that the cells of the brain often use the very same principles of organization and function as a humble bacterium or a liver cell, perhaps molecular biology and genetics could now interface with neuroscience to approach the tenuous relationship between genes and behavior, cognition, memory, emotion, and perception. This thinking was the result of a faculty meeting at which Eric Kandel and I overcame our boredom with administration by talking science. Eric was characteristically exuberant about his recent data that revealed a correlation between a simple form of memory in the marine snail, Aplysia and cellular memory at the level of a specific synapse. Molecular biologists had encountered cellular memory before in the self-perpetuating control of gene expression. This led to the realization that this was the moment to begin to apply the techniques of molecular biology to brain function and I would attempt to recruit Eric Kandel as my teacher.

A courageous new postdoctoral fellow in my laboratory, Richard Scheller, now Director of Research for Genentech, was excited about embarking on an initial effort in molecular neurobiology in a laboratory with absolutely no expertise in neuroscience. Together with Richard and Eric, we set out to isolate the genes responsible for the generation of stereotyped patterns of innate behaviors. All organisms exhibit innate behaviors that are shaped by evolution and inherited by successive generations that are largely unmodified by experience or learning. It seemed reasonable to assume that this innate behavior was dictated by genes that might be accessible to molecular cloning. It was an exciting and amusing time with myself unfamiliar with action potentials and Kandel uncomfortable with central dogma. Richard Scheller exploited the techniques of recombinant DNA to identify a family of genes encoding a set of related neuropeptides whose coordinated release is likely to govern the fixed action pattern of behaviors associated with egg laying. A single gene, the ELH gene, specifies a polyprotein that is cut into small biologically active peptides such that individual components of the behavioral array may be mediated by peptides encoded by one gene.

Watching the story unfold, observing the interface of molecular biology and neuroscience provided great pleasure. More importantly, this collaboration formed the basis of a continuing relationship with Eric Kandel, with his incisive mind, inimitable laugh and boundless energy. In 1986, neuroscience for me was made even richer when Tom Jessell came along. Tom joined the faculty at Columbia and was to occupy a lab adjacent to my own. Not surprisingly, the lab was not ready and I had the great pleasure of hosting Tom in my own laboratory and this forged a long-lasting scientific and personal relationship. Jessell, the understated British scientist with a wry wit and piercing mind, joined a fellow in my laboratory, David Julius, now at the University of California at San Francisco, and together they devised a clever assay for the isolation of genes encoding the neurotransmitter receptors. These experiments, which might have been the last performed by the hands of Jessell, led to the isolation of genes encoding the seven transmembrane domain serotonin receptor, 5HT1C, and more generally provided an expression system that permitted the identification of functional genes that encode receptors in the absence of any information on the nature of the protein sequence. With Kandel one floor above, and Jessell next door, there was no departure from neuroscience. I was surrounded and I did not want to escape. I was beginning to feel that neuroscience was indeed an appropriate occupation for a molecular biologist. To quote Woody Allen, a fellow New Yorker, “The brain is my second favorite organ.”

In the late 1980’s I became fascinated in the problem of perception: how the brain represents the external world. I was struck by observations from animal behavior that what an organism detects in its environment is only part of what is around it and that part can differ in different organisms. The brain functions then not by recording an exact image of the world but by creating its own selective picture. Biological reality will therefore reflect the particular representation of the external world that a brain is able to build and a brain builds with genes. If genes are indeed the arbiters of what we perceive from the outside world then it follows that an understanding of the function of these genes could provide insight into how the external world is represented in the brain. Together with Linda Buck, a creative fellow in the lab, we began to consider how the chemosensory world is represented in the brain. The problem of olfaction was a perfect intellectual target for a molecular biologist. How we recognize the vast diversity of odorous molecules posed a fascinating problem. We assumed that the solution would involve a large family of genes and Linda Buck devised a creative approach that indeed identified the genes encoding the receptors that recognize the vast array of odorants in the environment. Linda came to me with the experimental data late one night, exuberant, and I fell uncharacteristically silent. There were 1,000 odorant receptor genes in the rat genome, the largest family of genes in the chromosome and this provided the solution to the problem of the diversity of odor recognition. More importantly, the identification of these 10,000 genes and their expression revealed an early and unanticipated logic of olfaction. Indeed, the subsequent use of these genes to manipulate the genome of mice has afforded a view of how the olfactory world could be represented in the brain, how genes shape our perception of the sensory environment. From that late night moment to the present, it has been a joy to watch this story unfold.

It is this work for which Linda Buck and I share the profound honor and good fortune of having been awarded the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine. But there are deeper, more human joys, two sons, Adam and Jonathan, my sister, Linda, a very close coterie of friends, and a new love. Watching, contributing to the growth of my children is not only moving but humbling and puts my intense life in science in perspective. Often this intensity, bordering on obsession, distracted me from fathering and this is a regret. But my sons have emerged from a frenetic teenage into very human college students, extremely unlikely to pursue a career in science. My sister remains a close and dedicated member of an increasingly small family. A new love, Cori Bargmann, a behavioral geneticist now at Rockefeller University, has entered my world. Her intensity for science hides a knowledge and passion for books, music, and art. I have learned much from her but most importantly, Cori has shown me how to combine intellectual intensity with humanity and warmth.

Finally, the Nobel Prize was awarded to me not as a man, but for my work, a work of science that derives from the efforts of many brilliant students as well as from the incisive teachings of devoted colleagues. I take equal pride in the science that has been accomplished in the laboratory as in the scientists that have trained with me and are now independently contributing to our understanding of biology. I therefore feel that I can only accept the Nobel Prize in trust, as a representative of a culture of science in my laboratory and at Columbia University. I am deeply grateful for this culture.

This autobiography/biography was written at the time of the award and later published in the book series Les Prix Nobel/ Nobel Lectures/The Nobel Prizes. The information is sometimes updated with an addendum submitted by the Laureate.