Gao Xingjian – Nobel Symposia

Gao Xingjian – Banquet speech

Gao Xingjian’s speech at the Nobel Banquet, December 10, 2000 (in French)

Vos Majestés, Vos Altesses royales, Mesdames, Messieurs,

L’homme qui est devant vous se souvient encore qu’à l’âge de huit ans, sa mère lui avait demandé de tenir un journal. II s’est ainsi consacré à l’écriture jusqu’à l’âge adulte.

II se souvient encore qu’à son entrée au lycée, un vieux professeur de rédaction avait accroché au tableau une peinture sans en révéler le titre et avait demandé aux élèves de faire une rédaction à son sujet. L’homme qui est devant vous n’aimait pas cette peinture, et il avait écrit des critiques contre elle. Non seulement le vieux maître ne s’était pas mis en colère, mais il lui avait donné une bonne note assortie du commentaire : “Plume vigoureuse.” Et c’est ainsi que cet homme n’a plus cessé d’écrire, d’abord des contes pour enfants, puis des romans, de la poésie et du théâtre, et ce jusqu’à ce que la révolution renverse la culture. Là, pris de peur, il a tout brûlé.

Ensuite, il est parti cultiver les rizières pendant de nombreuses années. Mais il écrivait encore en secret et cachait ses manuscrits dans des pots de terre quite qu’il enterrait.

Ce qu’il a écrit ensuite a été interdit.

Plus tard encore, arrivé en Occident, il a continué à écrire, mais sans se soucier d’être édité. Et même quand il fut édité, il ne se soucia pas de connaître les réactions. Soudain, le voilà dans cette brillante salle, qui reçoit cette précieuse récompense des mains de Sa Majesté le Roi.

Alors, il ne peut s’empêcher de demander : Votre Majesté, est-ce la réalité ou un conte ?

Gao Xingjian – Prose

English

Swedish

French

Utdrag ur En ensam människas bibel

LIV DU LEVER INTE längre i någon annans skugga, och du inbillar dig inte att någon annans skugga är din fiende.

Du har vandrat ut ur skuggan och befinner dig i en stor stillhet. Du behöver inte längre hänge dig åt falska förhoppningar och fantasier. Naken och utan bekymmer kom du till världen, och du behöver inte ta någonting med dig när du lämnar den, och det kan du inte heller göra. Det enda du fruktar är döden, som du inte kan veta någonting om.

Du minns att du alltsedan barndomen har varit rädd för döden, och att den då ingav dig större fruktan än den gör nu. Så fort du drabbades av den minsta åkomma fruktade du att det var en dödlig sjukdom, och så fort du blev sjuk började du yra och fantisera och inbilla dig det värsta. Men trots att du har genomlidit en mängd sjukdomar och till och med varit nära döden lever du fortfarande i högönsklig välmåga. Livet är ett under, som trotsar beskrivning; det är i själva verket i levandet som undret förverkligas. Detta att en människa i sin levande kropp förmår förnimma den smärta och den glädje som livet skänker, är inte det tillräckligt? Vad mer finns där att söka?

Din rädsla för döden sätter in när dina själskrafter sviktar. Du får svårt för att andas och fruktar för att inte få tillräckligt mycket luft i lungorna. Du tycker dig störta ner i en avgrund. Känslan av att falla drabbade dig ofta i sömnen när du var liten, och du vaknade badande i svett. I själva verket var du aldrig sjuk när du var liten. Din mor tog dig flera gånger till sjukhuset för att undersökas, men nuförtiden bryr du dig inte om att undersöka din hälsa, även om din läkare skulle uppmana dig till det både en och två gånger.

Du är fullkomligt medveten om att livet har ett slut, och att smärtan samtidigt kommer att upphöra. Den fruktan är i sig själv en manifestation av livet: när du förlorar medvetandet upphör allt i ett enda ögonblick. Du behöver inte längre grubbla, och det är just sökandet efter livets mening som har skänkt dig smärta. Med dina ungdomsvänner diskuterade du den slutliga meningen med livet, men på den tiden hade du knappast hunnit börja leva. Nu, när du har smakat på allt som livet har att bjuda på, av ont och gott, finner du det både lönlöst och löjligt att söka dess mening. Då är det bättre att njuta av livet, samtidigt som du iakttar det.

Du tycker dig se honom i ett tomrum, belyst av ett svagt ljus, vars källa du inte kan bestämma. Han befinner sig inte på någon bestämd plats, men ändå förefaller han dig som ett träd som inte kastar någon skugga. Horisonten, som skiljer himlen från jorden, har också försvunnit. Ibland ter han sig som en fågel på en snöig mark som spanar åt höger och åt vänster och stundom tycks grubbla över någonting, men vad, det vet du inte. Det kanske bara är en attityd, en ganska vacker attityd, för existensen är ju när allt kommer omkring ingenting annat än en attityd, en i möjligaste mån angenäm attityd. Han svänger runt där han står med utsträckta armar och böjda knän och skådar tillbaka på sitt medvetande. Man borde kanske hellre säga att attityden är hans medvetande, att det är du som uppenbaras i hans medvetande, och att det är just det som skänker honom hemlig glädje.

Det finns inga tragedier, komedier eller farser, de är ingenting annat än estetiska värderingar av livet, som växlar med de inblandade personerna, med tiden och rummet. Det förhåller sig på samma sätt med känslan: när vad man känner här och nu transponeras till vad man kände där och då blir sorgen och löjet också utbytbara. Det behöver man inte längre göra sig lustig över: du har haft nog av självironi och självprövningar. Det räcker med att du lugnt och stilla håller fast vid din attityd till livet, gör ditt bästa för att njuta av livets under och känner dig till freds med dig själv, när du i din ensamhet begrundar din situation. Hur du framstår i hans ögon bryr du dig inte om.

Du vet inte vad du kan tänkas åstadkomma i framtiden, och inte heller vad som finns att göra, det behöver du inte bekymra dig om. Du gör vad du får lust att göra: går det bra är det okej, misslyckas du, så får det vara. Du ställs inte inför något val. När du är hungrig och törstig äter och dricker du. Självfallet har du dina synpunkter och dina preferenser, och ännu har du inte blivit så gammal att du inte längre kan gripas av vrede. Självfallet kan du fortfarande känna dig indignerad över någon orättvisa, men du blir inte längre lika upprörd. Dina känslor och din åtrå har du fortfarande kvar, och de får hänga med så länge de själva orkar, men hatet har du släppt eftersom det är så helt och hållet fruktlöst och därtill skadar dig själv.

Livet är det enda du bryr dig om, och det är det som får dig att känna att du fortfarande har något att ge. Du lyckas fortfarande intressera dig för och förvånas av nya upptäckter. Och nog är det väl så att det bara är livet som kan väcka ens entusiasm?

Utdrag ur En ensam människas bibel

Originalets titel: Yige ren de shengjing

Copyright © Gao Xingjian 1999

Copyright © Översättning av Göran Malmqvist 2000

Copyright © Bokförlaget Atlantis AB 2000

ISBN 91-7486-536-6

Gao Xingjian – Photo gallery

Gao Xingjian receiving his Nobel Prize from His Majesty King Carl XVI Gustaf of Sweden at the Stockholm Concert Hall, 10 December 2000.

Copyright © The Nobel Foundation 2000

Photo: Hans Mehlin

Gao Xingjian after receiving his Nobel Prize

from His Majesty the King at the Stockholm Concert Hall, 10 December 2000.

Copyright © The Nobel Foundation 2000

Photo: Hans Mehlin

The Nobel Prize Award Ceremony at the Stockholm Concert Hall.

Eric R. Kandel is first from left, front row.

Copyright © The Nobel Foundation 2000

Photo: Hans Mehlin

Gao Xingjian at the table of honour at the Nobel Banquet at the Stockholm City Hall, 10 December 2000.

Copyright © Pressens Bild AB 2000, SE-112 88 Stockholm, Sweden, telephone: +46 (0)8 738 38 00 Photo: Jonas Ekströmer

Literature laureate Gao Xingjian at CERN on 23 September 2015.

© 2015-2023 CERN. Photo: Sophia Elizabeth Bennett.

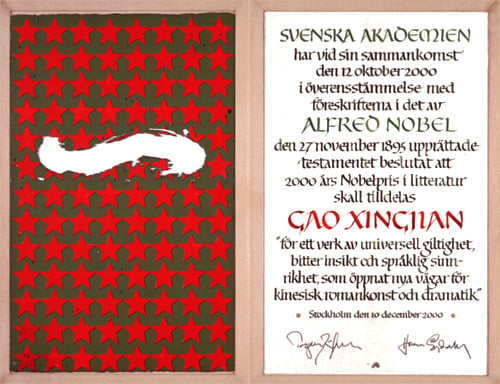

Gao Xingjian – Nobel diploma

Copyright © The Nobel Foundation 2000

Artist: Bo Larsson

Calligrapher: Annika Rücker

Gao Xingjian – Nobel Lecture

Gao Xingjian delivered his Nobel Lecture in Börssalen at the Swedish Academy in Stockholm, 7 December 2000. Xingjian was introduced by Horace Engdahl, Permanent Secretary of the Swedish Academy.

English

Swedish

Chinese (pdf)

10 December 2000

The Case for Literature

I have no way of knowing whether it was fate that has pushed me onto this dais but as various lucky coincidences have created this opportunity I may as well call it fate. Putting aside discussion of the existence or non-existence of God, I would like to say that despite my being an atheist I have always shown reverence for the unknowable.

A person cannot be God, certainly not replace God, and rule the world as a Superman; he will only succeed in creating more chaos and make a greater mess of the world. In the century after Nietzsche man-made disasters left the blackest records in the history of humankind. Supermen of all types called leader of the people, head of the nation and commander of the race did not baulk at resorting to various violent means in perpetrating crimes that in no way resemble the ravings of a very egotistic philosopher. However, I do not wish to waste this talk on literature by saying too much about politics and history, what I want to do is to use this opportunity to speak as one writer in the voice of an individual.

A writer is an ordinary person, perhaps he is more sensitive but people who are highly sensitive are often more frail. A writer does not speak as the spokesperson of the people or as the embodiment of righteousness. His voice is inevitably weak but it is precisely this voice of the individual that is more authentic.

What I want to say here is that literature can only be the voice of the individual and this has always been so. Once literature is contrived as the hymn of the nation, the flag of the race, the mouthpiece of a political party or the voice of a class or a group, it can be employed as a mighty and all-engulfing tool of propaganda. However, such literature loses what is inherent in literature, ceases to be literature, and becomes a substitute for power and profit.

In the century just ended literature confronted precisely this misfortune and was more deeply scarred by politics and power than in any previous period, and the writer too was subjected to unprecedented oppression.

In order that literature safeguard the reason for its own existence and not become the tool of politics it must return to the voice of the individual, for literature is primarily derived from the feelings of the individual and is the result of feelings. This is not to say that literature must therefore be divorced from politics or that it must necessarily be involved in politics. Controversies about literary trends or a writer’s political inclinations were serious afflictions that tormented literature during the past century. Ideology wreaked havoc by turning related controversies over tradition and reform into controversies over what was conservative or revolutionary and thus changed literary issues into a struggle over what was progressive or reactionary. If ideology unites with power and is transformed into a real force then both literature and the individual will be destroyed.

Chinese literature in the twentieth century time and again was worn out and indeed almost suffocated because politics dictated literature: both the revolution in literature and revolutionary literature alike passed death sentences on literature and the individual. The attack on Chinese traditional culture in the name of the revolution resulted in the public prohibition and burning of books. Countless writers were shot, imprisoned, exiled or punished with hard labour in the course of the past one hundred years. This was more extreme than in any imperial dynastic period of China’s history, creating enormous difficulties for writings in the Chinese language and even more for any discussion of creative freedom.

If the writer sought to win intellectual freedom the choice was either to fall silent or to flee. However the writer relies on language and not to speak for a prolonged period is the same as suicide. The writer who sought to avoid suicide or being silenced and furthermore to express his own voice had no option but to go into exile. Surveying the history of literature in the East and the West this has always been so: from Qu Yuan to Dante, Joyce, Thomas Mann, Solzhenitsyn, and to the large numbers of Chinese intellectuals who went into exile after the Tiananmen massacre in 1989. This is the inevitable fate of the poet and the writer who continues to seek to preserve his own voice.

During the years when Mao Zedong implemented total dictatorship even fleeing was not an option. The monasteries on far away mountains that provided refuge for scholars in feudal times were totally ravaged and to write even in secret was to risk one’s life. To maintain one’s intellectual autonomy one could only talk to oneself, and it had to be in utmost secrecy. I should mention that it was only in this period when it was utterly impossible for literature that I came to comprehend why it was so essential: literature allows a person to preserve a human consciousness.

It can be said that talking to oneself is the starting point of literature and that using language to communicate is secondary. A person pours his feelings and thoughts into language that, written as words, becomes literature. At the time there is no thought of utility or that some day it might be published yet there is the compulsion to write because there is recompense and consolation in the pleasure of writing. I began writing my novel Soul Mountain to dispel my inner loneliness at the very time when works I had written with rigorous self-censorship had been banned. Soul Mountain was written for myself and without the hope that it would be published.

From my experience in writing, I can say that literature is inherently man’s affirmation of the value of his own self and that this is validated during the writing, literature is born primarily of the writer’s need for self-fulfilment. Whether it has any impact on society comes after the completion of a work and that impact certainly is not determined by the wishes of the writer.

In the history of literature there are many great enduring works which were not published in the lifetimes of the authors. If the authors had not achieved self-affirmation while writing, how could they have continued to write? As in the case of Shakespeare, even now it is difficult to ascertain the details of the lives of the four geniuses who wrote China’s greatest novels, Journey to the West, Water Margin, Jin Ping Mei and Dream of Red Mansions. All that remains is an autobiographical essay by Shi Naian and had he not as he said consoled himself by writing, how else could he have devoted the rest of his life to that huge work for which he received no recompense during life? And was this not also the case with Kafka who pioneered modern fiction and with Fernando Pessoa the most profound poet of the twentieth century? Their turning to language was not in order to reform the world and while profoundly aware of the helplessness of the individual they still spoke out, for such is the magic of language.

Language is the ultimate crystallisation of human civilisation. It is intricate, incisive and difficult to grasp and yet it is pervasive, penetrates human perceptions and links man, the perceiving subject, to his own understanding of the world. The written word is also magical for it allows communication between separate individuals, even if they are from different races and times. It is also in this way that the shared present time in the writing and reading of literature is connected to its eternal spiritual value.

In my view, for a writer of the present to strive to emphasise a national culture is problematical. Because of where I was born and the language I use, the cultural traditions of China naturally reside within me. Culture and language are always closely related and thus characteristic and relatively stable modes of perception, thought and articulation are formed. However a writer’s creativity begins precisely with what has already been articulated in his language and addresses what has not been adequately articulated in that language. As the creator of linguistic art there is no need to stick on oneself a stock national label that can be easily recognised.

Literature transcends national boundaries — through translations it transcends languages and then specific social customs and inter-human relationships created by geographical location and history — to make profound revelations about the universality of human nature. Furthermore, the writer today receives multicultural influences outside the culture of his own race so, unless it is to promote tourism, emphasising the cultural features of a people is inevitably suspect.

Literature transcends ideology, national boundaries and racial consciousness in the same way as the individual’s existence basically transcends this or that -ism. This is because man’s existential condition is superior to any theories or speculations about life. Literature is a universal observation on the dilemmas of human existence and nothing is taboo. Restrictions on literature are always externally imposed: politics, society, ethics and customs set out to tailor literature into decorations for their various frameworks.

However, literature is neither an embellishment for authority or a socially fashionable item, it has its own criterion of merit: its aesthetic quality. An aesthetic intricately related to the human emotions is the only indispensable criterion for literary works. Indeed, such judgements differ from person to person because the emotions are invariably that of different individuals. However such subjective aesthetic judgements do have universally recognised standards. The capacity for critical appreciation nurtured by literature allows the reader to also experience the poetic feeling and the beauty, the sublime and the ridiculous, the sorrow and the absurdity, and the humour and the irony that the author has infused into his work.

Poetic feeling does not derive simply from the expression of the emotions nevertheless unbridled egotism, a form of infantilism, is difficult to avoid in the early stages of writing. Also, there are numerous levels of emotional expression and to reach higher levels requires cold detachment. Poetry is concealed in the distanced gaze. Furthermore, if this gaze also examines the person of the author and overarches both the characters of the book and the author to become the author’s third eye, one that is as neutral as possible, the disasters and the refuse of the human world will all be worthy of scrutiny. Then as feelings of pain, hatred and abhorrence are aroused so too are feelings of concern and love for life.

An aesthetic based on human emotions does not become outdated even with the perennial changing of fashions in literature and in art. However literary evaluations that fluctuate like fashions are premised on what is the latest: that is, whatever is new is good. This is a mechanism in general market movements and the book market is not exempted, but if the writer’s aesthetic judgement follows market movements it will mean the suicide of literature. Especially in the so-called consumerist society of the present, I think one must resort to cold literature.

Ten years ago, after concluding Soul Mountain which I had written over seven years, I wrote a short essay proposing this type of literature:

“Literature is not concerned with politics but is purely a matter of the individual. It is the gratification of the intellect together with an observation, a review of what has been experienced, reminiscences and feelings or the portrayal of a state of mind.”

“The so-called writer is nothing more than someone speaking or writing and whether he is listened to or read is for others to choose. The writer is not a hero acting on orders from the people nor is he worthy of worship as an idol, and certainly he is not a criminal or enemy of the people. He is at times victimised along with his writings simply because of other’s needs. When the authorities need to manufacture a few enemies to divert people’s attention, writers become sacrifices and worse still writers who have been duped actually think it is a great honour to be sacrificed.”

“In fact the relationship of the author and the reader is always one of spiritual communication and there is no need to meet or to socially interact, it is a communication simply through the work. Literature remains an indispensable form of human activity in which both the reader and the writer are engaged of their own volition. Hence, literature has no duty to the masses.”

“This sort of literature that has recovered its innate character can be called cold literature. It exists simply because humankind seeks a purely spiritual activity beyond the gratification of material desires. This sort of literature of course did not come into being today. However, whereas in the past it mainly had to fight oppressive political forces and social customs, today it has to do battle with the subversive commercial values of consumerist society. For it to exist depends on a willingness to endure the loneliness.”

“If a writer devotes himself to this sort of writing he will find it difficult to make a living. Hence the writing of this sort of literature must be considered a luxury, a form of pure spiritual gratification. If this sort of literature has the good fortune of being published and circulated it is due to the efforts of the writer and his friends, Cao Xueqin and Kafka are such examples. During their lifetimes, their works were unpublished so they were not able to create literary movements or to become celebrities. These writers lived at the margins and seams of society, devoting themselves to this sort of spiritual activity for which at the time they did not hope for any recompense. They did not seek social approval but simply derived pleasure from writing.”

“Cold literature is literature that will flee in order to survive, it is literature that refuses to be strangled by society in its quest for spiritual salvation. If a race cannot accommodate this sort of non-utilitarian literature it is not merely a misfortune for the writer but a tragedy for the race.”

It is my good fortune to be receiving, during my lifetime, this great honour from the Swedish Academy, and in this I have been helped by many friends from all over the world. For years without thought of reward and not shirking difficulties they have translated, published, performed and evaluated my writings. However I will not thank them one by one for it is a very long list of names.

I should also thank France for accepting me. In France where literature and art are revered I have won the conditions to write with freedom and I also have readers and audiences. Fortunately I am not lonely although writing, to which I have committed myself, is a solitary affair.

What I would also like to say here is that life is not a celebration and that the rest of the world is not peaceful as in Sweden where for one hundred and eighty years there has been no war. This new century will not be immune to catastrophes simply because there were so many in the past century, because memories are not transmitted like genes. Humans have minds but are not intelligent enough to learn from the past and when malevolence flares up in the human mind it can endanger human survival itself.

The human species does not necessarily move in stages from progress to progress, and here I make reference to the history of human civilisation. History and civilisation do not advance in tandem. From the stagnation of Medieval Europe to the decline and chaos in recent times on the mainland of Asia and to the catastrophes of two world wars in the twentieth century, the methods of killing people became increasingly sophisticated. Scientific and technological progress certainly does not imply that humankind as a result becomes more civilised.

Using some scientific -ism to explain history or interpreting it with a historical perspective based on pseudo-dialectics have failed to clarify human behaviour. Now that the utopian fervour and continuing revolution of the past century have crumbled to dust, there is unavoidably a feeling of bitterness amongst those who have survived.

The denial of a denial does not necessarily result in an affirmation. Revolution did not merely bring in new things because the new utopian world was premised on the destruction of the old. This theory of social revolution was similarly applied to literature and turned what had once been a realm of creativity into a battlefield in which earlier people were overthrown and cultural traditions were trampled upon. Everything had to start from zero, modernisation was good, and the history of literature too was interpreted as a continuing upheaval.

The writer cannot fill the role of the Creator so there is no need for him to inflate his ego by thinking that he is God. This will not only bring about psychological dysfunction and turn him into a madman but will also transform the world into a hallucination in which everything external to his own body is purgatory and naturally he cannot go on living. Others are clearly hell: presumably it is like this when the self loses control. Needless to say he will turn himself into a sacrifice for the future and also demand that others follow suit in sacrificing themselves.

There is no need to rush to complete the history of the twentieth century. If the world again sinks into the ruins of some ideological framework this history will have been written in vain and later people will revise it for themselves.

The writer is also not a prophet. What is important is to live in the present, to stop being hoodwinked, to cast off delusions, to look clearly at this moment of time and at the same time to scrutinise the self. This self too is total chaos and while questioning the world and others one may as well look back at one’s self. Disaster and oppression do usually come from another but man’s cowardice and anxiety can often intensify the suffering and furthermore create misfortune for others.

Such is the inexplicable nature of humankind’s behaviour, and man’s knowledge of his self is even harder to comprehend. Literature is simply man focusing his gaze on his self and while he does a thread of consciousness which sheds light on this self begins to grow.

To subvert is not the aim of literature, its value lies in discovering and revealing what is rarely known, little known, thought to be known but in fact not very well known of the truth of the human world. It would seem that truth is the unassailable and most basic quality of literature.

The new century has already arrived. I will not bother about whether or not it is in fact new but it would seem that the revolution in literature and revolutionary literature, and even ideology, may have all come to an end. The illusion of a social utopia that enshrouded more than a century has vanished and when literature throws off the fetters of this and that -ism it will still have to return to the dilemmas of human existence. However the dilemmas of human existence have changed very little and will continue to be the eternal topic of literature.

This is an age without prophecies and promises and I think it is a good thing. The writer playing prophet and judge should also cease since the many prophecies of the past century have all turned out to be frauds. And there is no need to manufacture new superstitions about the future, it is much better to wait and see. It would be best also for the writer to revert to the role of witness and strive to present the truth.

This is not to say that literature is the same as a document. Actually there are few facts in documented testimonies and the reasons and motives behind incidents are often concealed. However, when literature deals with the truth the whole process from a person’s inner mind to the incident can be exposed without leaving anything out. This power is inherent in literature as long as the writer sets out to portray the true circumstances of human existence and is not just making up nonsense.

It is a writer’s insights in grasping truth that determine the quality of a work, and word games or writing techniques cannot serve as substitutes. Indeed, there are numerous definitions of truth and how it is dealt with varies from person to person but it can be seen at a glance whether a writer is embellishing human phenomena or making a full and honest portrayal. The literary criticism of a certain ideology turned truth and untruth into semantic analysis, but such principles and tenets are of little relevance in literary creation.

However whether or not the writer confronts truth is not just an issue of creative methodology, it is closely linked to his attitude towards writing. Truth when the pen is taken up at the same time implies that one is sincere after one puts down the pen. Here truth is not simply an evaluation of literature but at the same time has ethical connotations. It is not the writer’s duty to preach morality and while striving to portray various people in the world he also unscrupulously exposes his self, even the secrets of his inner mind. For the writer truth in literature approximates ethics, it is the ultimate ethics of literature.

In the hands of a writer with a serious attitude to writing even literary fabrications are premised on the portrayal of the truth of human life, and this has been the vital life force of works that have endured from ancient times to the present. It is precisely for this reason that Greek tragedy and Shakespeare will never become outdated.

Literature does not simply make a replica of reality but penetrates the surface layers and reaches deep into the inner workings of reality; it removes false illusions, looks down from great heights at ordinary happenings, and with a broad perspective reveals happenings in their entirety.

Of course literature also relies on the imagination but this sort of journey in the mind is not just putting together a whole lot of rubbish. Imagination that is divorced from true feelings and fabrications that are divorced from the basis of life experiences can only end up insipid and weak, and works that fail to convince the author himself will not be able to move readers. Indeed, literature does not only rely on the experiences of ordinary life nor is the writer bound by what he has personally experienced. It is possible for the things heard and seen through a language carrier and the things related in the literary works of earlier writers all to be transformed into one’s own feelings. This too is the magic of the language of literature.

As with a curse or a blessing language has the power to stir body and mind. The art of language lies in the presenter being able to convey his feelings to others, it is not some sign system or semantic structure requiring nothing more than grammatical structures. If the living person behind language is forgotten, semantic expositions easily turn into games of the intellect.

Language is not merely concepts and the carrier of concepts, it simultaneously activates the feelings and the senses and this is why signs and signals cannot replace the language of living people. The will, motives, tone and emotions behind what someone says cannot be fully expressed by semantics and rhetoric alone. The connotations of the language of literature must be voiced, spoken by living people, to be fully expressed. So as well as serving as a carrier of thought literature must also appeal to the auditory senses. The human need for language is not simply for the transmission of meaning, it is at the same time listening to and affirming a person’s existence.

Borrowing from Descartes, it could be said of the writer: I say and therefore I am. However, the I of the writer can be the writer himself, can be equated to the narrator, or become the characters of a work. As the narrator-subject can also be he and you, it is tripartite. The fixing of a key-speaker pronoun is the starting point for portraying perceptions and from this various narrative patterns take shape. It is during the process of searching for his own narrative method that the writer gives concrete form to his perceptions.

In my fiction I use pronouns instead of the usual characters and also use the pronouns I, you, and he to tell about or to focus on the protagonist. The portrayal of the one character by using different pronouns creates a sense of distance. As this also provides actors on the stage with a broader psychological space I have also introduced the changing of pronouns into my drama.

The writing of fiction or drama has not and will not come to an end and there is no substance to flippant announcements of the death of certain genres of literature or art.

Born at the start of human civilisation, like life, language is full of wonders and its expressive capacity is limitless. It is the work of the writer to discover and develop the latent potential inherent in language. The writer is not the Creator and he cannot eradicate the world even if it is too old. He also cannot establish some new ideal world even if the present world is absurd and beyond human comprehension. However, he can certainly make innovative statements either by adding to what earlier people have said or else starting where earlier people stopped.

To subvert literature was Cultural Revolution rhetoric. Literature did not die and writers were not destroyed. Every writer has his place on the bookshelf and he has life as long as he has readers. There is no greater consolation for a writer than to be able to leave a book in humankind’s vast treasury of literature that will continue to be read in future times.

Literature is only actualised and of interest at that moment in time when the writer writes it and the reader reads it. Unless it is pretence, to write for the future only deludes oneself and others as well. Literature is for the living and moreover affirms the present of the living. It is this eternal present and this confirmation of individual life that is the absolute reason why literature is literature, if one insists on seeking a reason for this huge thing that exists of itself.

When writing is not a livelihood or when one is so engrossed in writing that one forgets why one is writing and for whom one is writing it becomes a necessity and one will write compulsively and give birth to literature. It is this non-utilitarian aspect of literature that is fundamental to literature. That the writing of literature has become a profession is an ugly outcome of the division of labour in modern society and a very bitter fruit for the writer.

This is especially the case in the present age where the market economy has become pervasive and books have also become commodities. Everywhere there are huge undiscriminating markets and not just individual writers but even the societies and movements of past literary schools have all gone. If the writer does not bend to the pressures of the market and refuses to stoop to manufacturing cultural products by writing to satisfy the tastes of fashions and trends, he must make a living by some other means. Literature is not a best-selling book or a book on a ranked list and authors promoted on television are engaged in advertising rather than in writing. Freedom in writing is not conferred and cannot be purchased but comes from an inner need in the writer himself.

Instead of saying that Buddha is in the heart it would be better to say that freedom is in the heart and it simply depends on whether one makes use of it. If one exchanges freedom for something else then the bird that is freedom will fly off, for this is the cost of freedom.

The writer writes what he wants without concern for recompense not only to affirm his self but also to challenge society. This challenge is not pretence and the writer has no need to inflate his ego by becoming a hero or a fighter. Heroes and fighters struggle to achieve some great work or to establish some meritorious deed and these lie beyond the scope of literary works. If the writer wants to challenge society it must be through language and he must rely on the characters and incidents of his works, otherwise he can only harm literature. Literature is not angry shouting and furthermore cannot turn an individual’s indignation into accusations. It is only when the feelings of the writer as an individual are dispersed in a work that his feelings will withstand the ravages of time and live on for a long time.

Therefore it is actually not the challenge of the writer to society but rather the challenge of his works. An enduring work is of course a powerful response to the times and society of the writer. The clamour of the writer and his actions may have vanished but as long as there are readers his voice in his writings continues to reverberate.

Indeed such a challenge cannot transform society. It is merely an individual aspiring to transcend the limitations of the social ecology and taking a very inconspicuous stance. However this is by no means an ordinary stance for it is one that takes pride in being human. It would be sad if human history is only manipulated by the unknowable laws and moves blindly with the current so that the different voices of individuals cannot be heard. It is in this sense that literature fills in the gaps of history. When the great laws of history are not used to explain humankind it will be possible for people to leave behind their own voices. History is not all that humankind possesses, there is also the legacy of literature. In literature the people are inventions but they retain an essential belief in their own self-worth.

Honourable members of the Academy, I thank you for awarding this Nobel Prize to literature, to literature that is unwavering in its independence, that avoids neither human suffering nor political oppression and that furthermore does not serve politics. I thank all of you for awarding this most prestigious prize for works that are far removed from the writings of the market, works that have aroused little attention but are actually worth reading. At the same time, I also thank the Swedish Academy for allowing me to ascend this dais to speak before the eyes of the world. A frail individual’s weak voice that is hardly worth listening to and that normally would not be heard in the public media has been allowed to address the world. However, I believe that this is precisely the meaning of the Nobel Prize and I thank everyone for this opportunity to speak.

Translation by Mabel Lee

Gao Xingjian – Prose

Excerpt from One Man’s Bible

by Gao Xingjian

English

Swedish

French

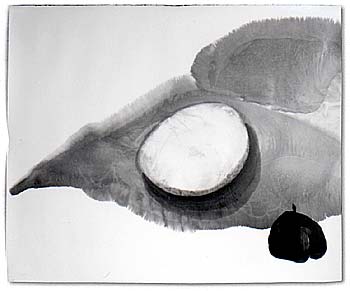

Painting by Gao Xingjian.

Excerpt from One Man’s Bible

54

You no longer live in other people’s shadows nor treat other people’s shadows as imaginary enemies. You just walked out of their shadows, stopped making up absurdities and fantasies, and are now in a vast emptiness and tranquillity. You originally came into the world naked and without cares and there is no need to take anything away with you, and if you wanted to you wouldn’t be able to. Your only fear is unknowable death.

You recall that your fear of death began in childhood and that your fear of death was much worse then than it is now. The slightest ailment made you worry that it was an incurable disease and when you fell ill you would think up all sorts of nonsense and be stricken with terror. Your having survived so many illnesses and even disasters is purely a matter of luck. Life in itself is an inexplicable miracle and to be alive is a manifestation of this miracle. Is it not enough that a conscious physical body is able to perceive the pains and joys of life? What else is there to be sought?

Your fear of death arises when you are mentally and physically frail. There is the feeling of not being able to breathe and you are anxious that you will not be able to last until you can take your next breath. It is as if you are falling in an abyss, this sensation of falling was often present in dreams during childhood and you would wake in fright drenched in perspiration. In those days there was nothing wrong and your mother took you for many hospital examinations, nowadays even under the doctor’s instruction to have an examination, you repeatedly procrastinate.

It is absolutely clear to you that life naturally ends and when the end comes the fear vanishes, for this fear is itself a manifestation of life. On losing awareness and consciousness life suddenly ends, allowing no further thought and no further meaning. Your affliction had been your search for meaning. When you began discussing the ultimate meaning of human life with friends of your youth you had hardly lived, it seems that now you have savoured virtually all of the sensations to be experienced in life you simply laugh at the futility of searching for meaning. It is best just to experience this existence and to take care of this existence.

You seem to see him in a vast emptiness, faint light comes from an unidentified source. He is not standing on some specific or defined patch of ground and he is like the trunk of a tree but has no shadow, and the horizon between the sky and the earth has vanished. Or, he is like a bird in some snow-covered place and is looking from one side to the other. Occasionally, he stares right ahead as if deep in thought, although it’s not clear what it is that he is pondering. It’s simply a gesture, a gesture of aesthetic beauty. Existence is actually a gesture, a striving for comfort, stretching the arms, bending the knees, turning around, to look back upon his consciousness. Or, it may be said that the gesture actually is his consciousness, that it is you in his consciousness, and from this he is able to gain some ephemeral happiness.

Tragedy, comedy and farce do not exist but are aesthetic judgements of human life that differ according to person, time and place. Feelings too are probably like this and the emotions of the present at some other time can fluctuate between the sentimental and the ludicrous. And there is no longer the need for mockery as self-ridicule or self-purification seem already to be enough. It is only in the gesture of tranquilly prolonging this life and striving to comprehend the mystery of this moment in time that freedom of existence is achieved, for in solitarily scrutinizing the self the perceptions of the self by others loses all relevance.

You don’t know what other things you will do or what else there is to do but this is of no concern. If you want to do something you proceed to do it, it’s fine if it is done but if it is not it doesn’t matter. And you do not have to persist in doing something for if at a particular moment you feel hungry and thirsty you simply go and have something to eat and drink. Of course you continue to have your own opinions, interpretations, tendencies and can even get angry as you haven’t got to the age when you no longer have the energy for anger. Naturally, you still become indignant but it is without a great deal of passion. Your capacity for feelings and sensory pleasures remains intact but as this is so then so be it. However there is no longer remorse, remorse is futile and, needless to say, damaging to the self.

For you only life is of value, you have a lingering attachment to it and it continues to be interesting as there are still things to discover and to amaze you, and it is only life that can excite you. That’s exactly how it is with you, isn’t it?

Copyright © Gao Xingjian 1999

Copyright © Translation by Mabel Lee 2000

Excerpt selected by the Nobel Library of the Swedish Academy

Gao Xingjian – Bibliography

| Works in Chinese |

| Xiandai xiaoshuo jiqiao chutan. – Guangzhou : Huacheng, 1981 |

| You zhi gezi jiao Hongchunr. – Beijing : Beijing Publishing House, 1985 |

| Gao Xingjian xiju ji. – Beijing : Qunzhong, 1985 |

| Dui yizhong xiandai xiju de zhuiqiu. – Beijing : China Theater Publishing House, 1988 |

| Gei wo laoye mai yugan. – Taipei : Lianhe, 1988 |

| Lingshan. – Taipei : Lianjing, 1990 |

| Shanhaijing zhuan. – Hong Kong : Cosmos, 1993 |

| Gao Xingjian xiju liuzhong. – Taipei : Dijiao, 1995. – 7 vol. |

| Meiyou zhuyi. – Hong Kong : Cosmos, 1996 |

| Zhoumo sichongzou. – Hong Kong : New Century, 1996 |

| Yige ren de shengjing. – Taipei : Lianjing, 1999 |

| Bayue xue. – Taipei : Lianjing, 2000 |

| Wenxue de liyou. – Hong Kong : Ming Pao, 2001 |

| Gao Xingjian juzuo xuan. – Hong Kong : Ming Pao, 2001 |

| Ling yizhong meixue. – Taipei : Lianjing, 2001 |

| Gao Xingjian duanpian xiaoshuo ji. – Taipei : Lianhe, 2001 |

| Lun chuang zuo. – Taipei : Lianjing, 2008 |

| A selection of works by Gao Xingjian in English |

| Wild Man: a Contemporary Chinese Spoken Drama / transl. and annotated by Bruno Roubicek // Asian Theatre Journal. Vol. 7, Nr 2. Fall 1990. |

| Fugitives / transl. by Gregory B. Lee // Lee, Gregory B., Chinese Writing and Exile. – Center of East Asian Studies at the University of Chicago, 1993. |

| The Other Shore: Plays by Gao Xingjian / transl. by Gilbert C.F. Fong. – Hong Kong: The Chinese University Press, 1999. |

| Soul Mountain / transl. by Mabel Lee. – HarperCollins, 1999. |

| One Man’s Bible. – [In transl. by Mabel Lee] |

| Contemporary Technique and National Character in Fiction / transl. by Ng Mau-sang. – [Extract from A Preliminary Discussion of the Art of Modern Fiction, 1981] |

| The Voice of the Individual // Stockholm Journal of East Asian Studies 6, 1995. |

| Without Isms / transl. by W. Lau, D. Sauviat & M. Williams // Journal of the Oriental Society of Australia. Vols 27 & 28, 1995–96. |

| One Man’s Bible : a Novel / translated from the Chinese by Mabel Lee. – London : Flamingo, 2002 ; New York : HarperCollins, 2002. – Uniform Title: Yi ge ren de sheng jing |

| Return to Painting / translated from the French by Nadia Benabid. – New York : Perennial, cop. 2002. – Uniform Title: Pour une autre esthétique |

| Ink Paintings by Gao Xingjian : Nobel Prize Winner. – Dumont, NJ : Homa & Sekey Books, 2002 |

| Buying a Fishing Rod for My Grandfather : Stories / translated from the Chinese by Mabel Lee. – London : Flamingo, 2002 ; New York : HarperCollins, cop. 2004. – Uniform Title: Gei wo lao ye mai yu gan |

| Cold Literature : Selected Works by Gao Xingjian – Chinsese-English bilingual ed. / original Chinese text by Gao Xingjian translated by Cilbert C.F. Fong and Mabel Lee. – Sha Tin, N.T., Hong Kong : The Chinese Univ. Press, 2005 |

| The Case for Literature / translated from the Chinese by Mabel Lee. – New Haven : Yale University Press, 2007 |

| Of Mountains and Seas : a Tragicomedy of the Gods in Three Acts / translated by Gilbert C.F. Fong. – Hong Kong : Chinese University Press, 2008 |

| Gao Xingjian : Aesthetics and Creation / translated by Mabel Lee. – Amherst, NY : Cambria Press, 2013 |

| Critical studies |

| Trees on the Mountain : an Anthology of New Chinese Writing / ed. by Stephen C. Soong and John Minford. – Hong Kong: The Chinese U.P., cop. 1984. |

| Gao Xingjian, le moderniste // La Chine aujourd’hui No 41, septembre 1986. |

| Basting, Monica, Yeren : Tradition und Avantgarde in Gao Xingjians Theaterstück “Die Wilden”. – Bochum: Brockmeyer, 1988. |

| Lodén, Torbjörn, World Literature with Chinese Characteristics: On a Novel by Gao Xingjian // Stockholm Journal of East Asian Studies 4, 1993. |

| Lee, Gregory B., Chinese Writing and Exile. – Center of East Asian Studies at the University of Chicago, 1993. |

| Lee, Mabel, Without Politics: Gao Xingjian on Literary Creation // Stockholm Journal of East Asian Studies 6, 1995. |

| Lee, Mabel, Pronouns as Protagonists : Gao Xingjian’s Lingshan as Autobiography // Colloquium of the Sydney Society of Literature and Aesthetics at the Univ. of Sydney. Draft paper the 3–4 Oct. 1996. |

| Lee, Mabel, Personal Freedom in Twentieth-Century China: Reclaiming the Self in Yang Lian’s Yi and Gao Xingjian’s Lingshan // History, Literature and Society. – Sydney: Sydney Studies in Society and Culture 15, 1996. |

| Au plus près du réel: dialogues sur l’écriture 1994–1997, entretiens avec Denis Bourgeois / trad. par Noël et Liliane Dutrait. – La Tour d’Aigues: l’Aube, 1997. |

| Lee, Mabel, Gao Xingjian’s Lingshan / Soul Mountain: Modernism and the Chinese Writer // Heat 4, 1997. |

| Calvet, Robert, Gao Xingjian, le peintre de l’âme // Brèves No 56, hiver 1999. |

| Zhao, Henry Y.H., Towards a Modern Zen Theatre: Gao Xingian and Chinese Theatre Experimentalism. – London: School of Oriental and African Studies, 2000. |

| Soul of Chaos : Critical Perspectives on Gao Xingjian / edited by Kwok-kan Tam. – Hong Kong : The Chinese University Press, 2001 |

| Draguet, Michel, Gao Xingjian : le goût de l’encre. – Paris : Hazan, 2002 |

| Quah, Sy Ren, Gao Xingjian and Transcultural Chinese Theater. – Honolulu : University of Hawai’i Press, 2004 |

The Swedish Academy, 2013

Gao Xingjian – Prize presentation

Watch a video clip of the 2000 Nobel Laureate in Literature, Gao Xingjian, receiving his Nobel Prize medal and diploma during the Nobel Prize Award Ceremony at the Concert Hall in Stockholm, Sweden, on 10 December 2000.

Gao Xingjian – Prose

English

Swedish

French

Le Livre d’un homme seul

Chapitre 54

Tu ne vis plus dans l’ombre de personne et tu ne considères plus l’ombre d’autrui comme un ennemi imaginaire, tu es sorti de cette ombre et voilà tout, tu ne vas pas te fabriquer espoirs et illusions, à l’origine, tu es arrivé dans ce monde sans le moindre souci, nu comme un ver, dans le vide et le calme le plus parfait, tu n’as pas besoin d’emporter quoi que ce soit, et de toute façon, même si tu le voulais, tu ne le pourrais pas, tu as peur seulement de la mort inconnue.

Tu te souviens que tu as peur de la mort depuis ton enfance, à l’époque tu en avais beaucoup plus peur que maintenant, à la moindre maladie tu croyais avoir attrapé un mal incurable, dès que tu souffrais d’une affection, tu te sentais complètement bouleversé, tu étais dans un état de panique totale, à l’heure d’aujourd’hui, tu as connu beaucoup de souffrances dues à la maladie et tu as été plongé dans de profondes détresses, être encore de ce monde tient de la chance, la vie est un miracle, mais on ne peut pas dire que vivre est la manifestation de ce miracle, n’est-ce pas déjà bien si un corps doué de conscience peut ressentir les souffrances et les plaisirs de la vie ? Que rechercher de plus ?

Tu as eu peur de la mort quand tes forces diminuaient, tu as eu l’impression d’être à bout de souffle, craint de ne pas arriver à reprendre ta respiration, comme si tu tombais au fond d’un gouffre, une impression qui apparaissait souvent dans tes rêves d’enfant, te réveillant et te laissant couvert de sueur, alors qu’en fait tu ne souffrais d’aucun mal, ta mère t’avait emmené plusieurs fois a l’hôpital pour te faire examiner ; aujourd’hui, tu n’as plus envie de te faire examiner, même si le médecin le recommandait, tu laisserais traîner les choses.

Il t’apparaissait clairement aussi que la vie connaissait une fin ; au moment de cette fin, la peur s’évanouirait simultanément, cette peur était finalement la manifestation de la vie, à l’instant où la conscience et la connaissance disparaîtraient, tout serait fini en un instant, sans laisser le temps de réaliser, et sans que cela ait un sens. La recherche du sens avait été ta souffrance : avec ton camarade d’enfance, tu discutais déjà sur le sens final de la vie, pourtant à l’époque tu n’avais guère vécu, alors qu’à présent tu en as goûté toutes les saveurs, il est vain et inutile de rechercher ce sens, tu sombrerais dans le ridicule, mieux vaut profiter de l’existence, et en même temps l’observer.

Il te semble le voir, lui, dans une sorte de vide, une petite lumière arrive d’on ne sait où, il est debout sur une terre ni fixe ni déterminée, il est comme un tronc d’arbre sans ombre portée, l’horizon a disparu, ou alors il est comme un oiseau sur une étendue de neige, tournant la tête à gauche et à droite, par moments il fixe son regard, comme s’il réfléchissait. À quoi ? Ce n’est pas clair du tout, mais c’est une attitude, une attitude quand même assez belle ; exister c’est prendre une attitude, la plus agréable possible, bras écartés, agenouillé et se tournant, il revient sur sa conscience, ou mieux vaut dire que son attitude est justement sa conscience, c’est le tu au milieu de sa conscience, dont il tire un plaisir secret.

Il n’y a ni tragédie, ni comédie, ni farce, tout cela ce sont des jugements esthétiques envers la vie, des différences d’appréciation en fonction des gens, des moments et des lieux ; il en est de même du lyrisme : tel sentiment à tel moment ne sera pas le même à un autre moment, tristesse et ridicule sont à un certain point interchangeables, il n’est plus besoin de railler, l’autodérision et la purification de soi suffisent, il suffit de persévérer tranquillement dans cette façon de vivre, s’efforcer de goûter les merveilles de l’instant, se sentir à l’aise, et quand on s’examine, seul avec soi-même, ne plus s’occuper du regard des autres.

Tu ne sais pas ce que tu seras encore capable de faire, et ce qu’il te reste encore à faire, inutile d’y penser, fais ce que tu as envie de faire, si c’est réussi tant mieux, sinon tant pis, que ce soit fait ou non n’a pas d’importance, si tu as faim ou soif bois ou mange, bien sûr tu auras comme toujours ton point de vue, ta conception des choses, tes inclinations et même tes colères, tu n’es pas encore à l’âge où tu n’auras plus la force de te mettre en colère, naturellement tu auras toujours tes justes indignations, pourtant ce n’est plus la même excitation, mais tu éprouves toujours autant de sentiments et de désirs ; s’ils existent, laisse-les exister, mais la rancune a disparu puisqu’elle est parfaitement vaine et peut même te nuire.

Tu n’accordes de l’importance qu’à la vie, tu éprouves grâce à elle des sentiments inachevés, et tu te ménages encore de l’intérêt pour la découverte et la surprise, seule la vie mérite que l’on s’enthousiasme, n’est-ce pas ainsi ?

Traduit du chinois par Noël et Liliane Dutrait

Copyright © Yigeren de Shengjing, Lianjing, Taipei, 1999

Copyright © Éditions de l’Aube, 2000, pour la traduction française

ISBN 2-87678-538-2