Jens C. Skou – Biographical

I was born on the 8th of October 1918 into a wealthy family in Lemvig, a town in the western part of Denmark. The town is nicely situated on a fjord, which runs across the country from the Kattegat in East to the North Sea in West. It is surrounded by hills, and is only 10 km, i.e. bicycling distance, from the North Sea, with its beautiful beaches and dunes. My father Magnus Martinus Skou together with his brother Peter Skou were timber and coal merchants.

We lived in a big beautiful house, had a nice summer house on the North Sea coast. We were four children, I was the oldest with a one year younger brother, a sister 4 years younger and another brother 7 years younger. The timber-yard was an excellent playground, so the elder of my brothers and I never missed friends to play with. School was a minor part of life.

When I was 12 years old my father died from pneumonia. His brother continued the business with my mother Ane-Margrethe Skou as passive partner, and gave her such conditions that there was no change in our economical situation. My mother, who was a tall handsome woman, never married again. She took care of us four children and besides this she was very active in the social life in town.

When I was 15, I went to a boarding school, a gymnasium (high school) in Haslev a small town on Zealand, for the last three years in school (student exam). There was no gymnasium in Lemvig.

Besides the 50-60 boys from the boarding section of the school there were about 400 day pupils. The school was situated in a big park, with two football fields, facilities for athletics, tennis courts and a hall for gymnastics and handball. There was a scout troop connected to the boarding section of the school. I had to spend a little more time preparing for school than I was used to. My favourites were the science subjects, especially mathematics. But there was plenty of time for sports activities and scouting, which I enjoyed. All the holidays, Christmas, Easter, summer and autumn I spent at home with my family.

After three years I got my exam, it was in 1937. I returned to Lemvig for the summer vacation, considering what to do next. I could not make up my mind, which worried my mother. I played tennis with a young man who studied medicine, and he convinced me that this would be a good choice. So, to my mother’s great relief, I told her at the end of August that I would study medicine, and started two days later at the University of Copenhagen.

The medical course was planned to take 7 years, 3 years for physics, chemistry, anatomy, biochemistry and physiology, and 4 years for the clinical subjects, and for pathology, forensic medicine, pharmacology and public health. I followed the plan and got my medical degree in the summer of 1944.

I was not especially interested in living in a big town. On the other hand it was a good experience for a limited number of years to live in, and get acquainted with the capital of the country, and to exploit its cultural offers. Art galleries, classical music and opera were my favourites.

For the first three years I spent the month between the semesters at home studying the different subjects. For the last 4 years the months between the semesters were used for practical courses in different hospital wards in Copenhagen.

It was with increasing anxiety that we witnessed to how the maniac dictator in Germany, just south of our border, changed Germany into a madhouse. Our anxiety did not become less after the outbreak of the war. In 1914 Denmark managed to stay out of the war, but this time, in April 1940 the Germans occupied the country. Many were ashamed that the Danish army were ordered by the government to surrender after only a short resistance. Considering what later happened in Holland, Belgium and France, it was clear that the Danish army had no possibility of stopping the German army.

The occupation naturally had a deep impact on life in Denmark in the following years, both from a material point of view, but also, what was much worse, we lost our freedom of speech. For the first years the situation was very peculiar. The Germans did not remove the Danish government, and the Danish government did not resign, but tried as far as it was possible to minimize the consequences of the occupation. The army was not disarmed, nor was the fleet. The Germans wanted to use Denmark as a food supplier, and therefore wanted as few problems as possible.

The majority of the population turned against the Germans, but with no access to weapons, and with a flat homogeneous country with no mountains or big woods to hide in, the possibility of active resistance was poor. So for the first years the resistance only manifested itself in a negative attitude to the Germans in the country, in complicating matters dealing with the Germans as far as possible, and in a number of illegal journals, keeping people informed about the situation, giving the information which was suppressed by the German censorship. There was no interference with the teaching of medicine.

The Germans armed the North Sea coast against an invasion from the allied forces. Access was forbidden and our summer house was occupied. My grandmother had died in 1939, and we four children inherited what would have been my father’s share. For some of the money my brother and I bought a yacht, and took up sailing, and this has since been an important part of my leisure time life. After the occupation the Germans had forbidden sailing in the Danish seas except on the fjord where Lemvig was situated, and another fjord in Zealand.

The resistance against the Germans increased as time went on, and sabotage slowly started. Weapons and ammunition for the resistance movement began to be dropped by English planes, and in August 1943 there were general strikes all over the country against the Germans with the demand that the Government stopped giving way to the Germans. The Government consequently resigned, the Germans took over, the Danish marine sank the fleet and the army was disarmed. An illegal Frihedsråd (the Danish Liberation Council) revealed itself, which from then on was what people listened to and took advice from.

Following this, the sabotage against railways and factories working for the Germans increased, and with this arrests and executions. One of our medical classmates was a German informer. We knew who he was, so we could take care. He was eventually liquidated by unknowns. We feared a reaction from Gestapo against the class, and stayed away from the teaching.

The Germans planned to arrest the Jews, but the date, the night between the first and second October 1943 was revealed by a high placed German. By help from many, many people the Jews were hidden. Of about 7000, the Germans caught 472, who were sent to Theresienstadt where 52 died. In the following weeks illegal routes were established across the sea, Øresund, to Sweden, and the Jews were during the nights brought to safety. From all sides of the Danish society there were strong protests against the Germans for this encroachment on fellow-countrymen.

In May and June 1944, we managed to get our exams. A number of our teachers had gone underground, but their job was taken over by others. We could not assemble to sign the Hippocratic oath, but had to come one by one at a place away from the University not known by others.

I returned to my home for the summer vacation. The Germans had taken over part of my mother’s house, and had used it for housing Danes working for the Germans. This was extremely unpleasant for my mother, but she would not leave her house and stayed. I addressed the local German commander, and managed to get him to move the “foreigners” from the house at least as long as we four children were home on holiday.

The Germans had forbidden sailing, but not rowing, so we bought a canoe and spent the holidays rowing on the fjord.

After the summer holidays I started my internship in a hospital in Hjørring in the northern part of the country. I first spent 6 months in the medical ward, and then 6 months in the surgical ward. I became very interested in surgery, not least because the assistant physician, next in charge after the senior surgeon, was very eager to teach me how to make smaller operations, like removing a diseased appendix. I soon discovered why. When we were on call together and we during the night got a patient with appendicitis, it happened–after we had started the operation–that he asked me to take over and left. He was then on his way to receive weapons and explosives which were dropped by English planes on a dropping field outside Hjørring. I found that this was more important than operating patients for appendicitis, but we had of course to take care of the patients in spite of a war going on. He was finally caught by the Gestapo, and sent to a concentration camp, fortunately not in Germany, but in the southern part of Denmark, where he survived and was released on the 5th of May 1945, when the Germans in Denmark surrendered.

I continued for another year in the surgical ward. It was here I became interested in the effect of local anaesthetics, and decided to use this as a subject for a thesis. Thereafter I got a position at the Orthopaedic Hospital in Aarhus as part of the education in surgery.

In 1947 I stopped clinical training, and got a position at the Institute for Medical Physiology at Aarhus University in order to write the planned doctoral thesis on the anaesthetic and toxic mechanism of action of local anaesthetics.

During my time in Hjørring I met a very beautiful probationer, Ellen Margrethe Nielsen, with whom I fell in love. I had become ill while I was on the medical ward, and spent some time in bed in the ward. I had a single room and a radio, so I invited her to come in the evening to listen to the English radio, which was strictly forbidden by the Germans – but was what everybody did.

After she had finished her education as a nurse in 1948, she came to Aarhus and we married. In 1950 we had a daughter, but unfortunately she had an inborn disease and died after 1 1/2 years. Even though this was very hard, it brought my wife and I closer together. In 1952, and in 1954 respectively we got two healthy daughters, Hanne and Karen.

The salary at the University was very low, so partly because of this but also because I was interested in using my education as a medical doctor, I took in 1949 an extra job as doctor on call one night a week. It furthermore had the advantage that I could get a permission to buy a car and to get a telephone. There were still after war restrictions on these items.

I was born in a milieu which politically was conservative. The job as a doctor on call changed my political attitude and I became a social democrat. I realized how important it is to have free medical care, free education with equal opportunities, and a welfare system which takes care of the weak, the handicapped, the old, and the unemployed, even if this means high taxes. Or as phrased by one of our philosophers, N.F.S. Grundtvig, “a society where few have too much, and fewer too little”.

We lived in a flat, so the car gave us new possibilities. We wanted to have a house, and my mother would give us the payment, but I was stubborn, and wanted to earn the money myself. In 1957 we bought a house with a nice garden in Risskov, a suburb to Aarhus not far away from the University.

I am a family man, I restricted my work at the Institute to 8 hours a day, from 8 to 4 or 9 to 5, worked concentratedly while I was there, went home and spent the rest of the day and the evening with my wife and children. All weekends and holidays, and 4 weeks summer holidays were spent with the family. In 1960 we bought an acre of land on a cliff facing the beach 45 minutes by car from Aarhus, and built a small summer house. From then on this became the centre for our leisure time life. We bought a dinghy and a rowing boat with outboard motor and I started to teach the children how to sail, and to fish with fishing rod and with net.

Later, when the girls grew older, we bought a yacht, the girls and I sailed in the Danish seas, and up along the west coast of Sweden. My wife easily gets seasick, but joined us on day tours. Later the girls took their friends on sail tours.

In wintertime the family skied as soon as there was snow. A friend of mine, Karl Ove Nielsen, a professor of physics, took me in the beginning of the 1960s at Easter time on an 8-day cross country ski tour through the high mountain area in Norway, Jotunheimen. We stayed overnight in the Norwegian Tourist Association’s huts on the trail, which were open during the Easter week. It was a wonderful experience, but also a tour where you had to take all safety precautions. It became for many years a tradition. Later the girls joined us, and they also took some of their friends. When the weather situation did not allow this tour, we spent a week in more peaceful surroundings either in Norway with cross-country skiing or in the Alps with slalom. We still do, now with the girls, their husbands and the grandchildren. Outside the sporting activities, I spend much time listening to classical music, and reading, first of all biographies.

When the children left home, one for studying medicine and the other architecture, my wife worked for several years as a nurse in a psychiatric hospital for children, then engaged herself in politics. She was elected for the County Council for the social democrats, and spent 12 years on the council, first of all working with health care problems. She was also elected to the county scientific ethical committee, which evaluates all research which involves human beings. Later she was elected co-chairman to the Danish Central Scientific Ethical Committee, which lay down the guidelines for the work on the local committees, and which is an appeal committee for the local committees as well as for the doctors. She has worked 17 years on the committees and has been lecturing nurses and doctors about ethical problems.

I had no scientific training when I started at the Institute of Physiology in 1947. It took me a good deal of time before I knew how to attack the problem I was interested in and get acquainted with this new type of work. The chairman, Professor Søren L. Ørskov was a very considerate person, extremely helpful, patient, and gave me the time necessary to find my feet. During the work I got so interested in doing scientific work that I decided to continue and give up surgery. The thesis was published as a book in Danish in 1954, and written up in 6 papers published in English. The work on the local anaesthetics, brought me as described in the following paper to the identification of the sodium-potassium pump, which is responsible for the active transport of sodium and potassium across the cell membrane. The paper was published in 1957. From then on my scientific interest shifted from the effect of local anaesthetics to active transport of cations.

In the 1940s and the first part of the 1950s, the amount of money allocated for research was small. Professor Ørskov, fell chronically ill. His illness developed slowly so he continued in his position, but I, as the oldest in the department after him, had partly to take over his job. This meant that besides teaching in the semesters I had to spend two months per year examining orally the students in physiology.

The identification of the sodium-potassium pump gave us contact to the outside scientific world. In 1961, I met R.W. Berliner at an international Pharmacology meeting in Stockholm. He mentioned the possibility of obtaining a grant from National Institutes of Health (NIH). I applied and got a grant for two years. The importance of this was not only the money, but that it showed interest in the work we were doing.

In 1963, Professor Ørskov resigned and I was appointed professor and chairman. In the late 1950s and especially in the 1960s, more money was allocated to the Universities, and also more positions. Due to the work with the sodium-potassium pump, it became possible to attract clever young people, and the institute staff in a few years increased from 4 to 20-25 scientists. This had also an effect on the teaching. I got a young doctor, Noe Næraa, who had expressed ideas about medical teaching, to accept a position at the Institute. He started to reorganise our old fashioned laboratory course, we got new modern equipment, and thereafter we also reorganised the teaching, made it problem-oriented with teaching in small classes. My scientific interest was membrane physiology, but I wanted also to find people who could cover other aspects of physiology, so we ended up with 5-6 groups who worked scientifically with different physiological subjects.

In 1972 we got a new statute for the Universities, which involved a democratization of the whole system. The chairman was no longer the professor (elected by the board of chairmen which made up the faculty), but he/she was now elected by all scientists and technicians in the Institute and could be anybody, scientist or technician. This was of course a great relief for me because I could get rid of all my administrative duties. A problem was, however, that I got elected as chairman, but later others took over. In the beginning it was very tedious to work with the system, not least because everybody thought that they should be asked and take part in every decision. Later we learned to hand over the responsibility to an elected board at the Institute.

In these years the money to the Institutes came from the Faculty, which got it from the University (which got it from the State). The money was then divided inside the institute by the chairman, and later by the elected board. It was usually sufficient to cover the daily expenses of the research. External funds were only for bigger equipment. Besides research-money we had a staff of very well trained laboratory assistants, whose positions–as well as the positions of the scientific staff–was paid by the University. The institute every year sent a budget for the coming year, to the faculty, who then sent a budget for the faculty to the University, and the University to the State.

This way of funding had the great advantage that there was not a steady pressure on the scientists for publication and for sending applications for external funds. It was a system that allowed everybody to start on his/her own project, independently, and test their ideas. Nobody was forced from lack of money to join a group which had money and work on their ideas. It was also a system which could be misused, by people who were not active scientifically. With an elected board it proved difficult to handle such a situation. Not least because the very active scientists tried to avoid being elected – i.e. it could be the least active who actually decided. In practice, however, the not very active scientists usually accepted to do an extra job with the teaching, thus relieving the very active scientists from part of the teaching burden.

In the 1980s this was changed, the money for science was transferred to centralized (state) funds, and had to be applied for by the individual scientist. Not an advantage from my point of view. Applications took a lot of time, it tempted a too fast publication, and to publish too short papers, and the evaluation process used a lot of manpower. It does not give time to become absorbed in a problem as the previous system.

My research interest was concentrated around the structure and function of the active transport system, the Na+,K+-ATPase. A number of very excellent clever young scientists worked on different sides of the subject, either their own choice or suggested by me. Each worked independent on his/her subject. Scientists who took part in the work on the Na+,K+-ATPase and who made important contributions to field were, P.L. Jørgensen (purification and structure), I. Klodos (phosphorylation), O. Hansen (effect of cardiac glycosides and vanadate), P. Ottolenghi (effect of lipids), J. Jensen (ligand binding), J. G. Nørby (phosphorylation, ligand binding, kinetics), L. Plesner (kinetics), M. Esmann (solubilization of the enzyme, molecular weight, ESR studies), T. Clausen (hormonal control), A.B. Maunsbach and E. Skriver from the Institute of Anatomy in collaboration with P.L. Jørgensen (electron microscopy and crystallization), and I. Plesner from the Department of Chemistry (enzyme kinetics and evaluation of models). We also had many visitors.

We got many contacts to scientists in different parts of the world, and I spent a good deal of time travelling giving lectures. In 1973 the first international meeting on the Na+,K+-ATPase was held in New York. The next was 5 years later in Århus, and thereafter every third year. The proceedings from these meetings have been a very valuable source of information about the development of the field.

My wife joined me on many of the tours and we got friends abroad. Apart from the scientific inspiration the travelling also gave many cultural experiences, symphony concerts, opera and ballet, visits to Cuzco and Machu Picchu in Peru, to Uxmal and Chichén Itzá on the Yucatan Peninsula, and to museums in many different countries. Not to speak of the architectural experiences from seeing many different parts of the world. And not least it gave us good friends.

It is not always easy to keep your papers in order when travelling. Sitting in the airport in Moscow in the 1960s waiting for departure to Khabarovsk in the eastern part of Siberia, we–three Danes on our way to a meeting in Tokyo–realized that we had forgotten our passports at the hotel in town. There were twenty minutes to departure and no way to get the passports in time. We asked Intourist what to do. There was only one boat connection a week from Nakhodka, where we should embark to Yokohama, so they suggested that we should go on, they would send the passports after us. I had once had a nightmare, that I should end my days in Siberia. When we after an overnight flight arrived in Khabarovsk we were met by a lady who asked if we were the gentlemen without passports. We could not deny, and she told us that they would not arrive until after we had left Khabarovsk by train to Nakhodka. But they would send them by plane to Vladivostok and from there by car to Nakhodka. To our question if we could leave Siberia without our passports the answer was no. When the train the following morning stopped in Nakhodka, a man came into the sleeping car and asked if we were the gentlemen without passports. To our “yes” he said “here you are”, and handed over the passports. Amazing. We had an uncomplicated boat trip to Yokohama.

It was not as easy some years later in Argentina. I had been at a meeting in Mendoza, had stopped in Cordoba on the way, had showed passport in and out of the airports without problems. Returning to Buenos Aires to leave for New York, the man at the counter told me that my passport had expired three months earlier, and according to rules I had to return direct to my home country. I argued that I was sure I could get into the U.S., but he would not give way. We discussed for half an hour. Finally shortly before departure he would let me go to New York if he could reserve a plane out of New York to Denmark immediately after my arrival. He did the reservation, put a label on my ticket with the time of departure, and by the second call for departure I rushed off, hearing him saying “You can always remove the label”. In New York, I stepped to the rear end of the line, hoping the man at the counter would be tired when it was my turn. He was not. I asked if I had to return to Denmark. “There is always a way out” was his answer, “No, go to the other counter, sign some papers, pay 5 dollars, and I let you in”.

In 1977, I was offered the chair of Biophysics at the medical faculty. It was a smaller department, with 7 positions for scientists, of which 5 were empty, which meant that we could get positions for I. Klodos and M. Esmann, who had fellowships. Besides J. G. Nørby and L. Plesner moved with us. The two members in the Institute, M. J. Mulvany and F. Cornelius became interested in the connection between pump activity and vasoconstriction, and reconstitution of the enzyme into liposomes, respectively, i.e. all in the institute worked on different sides of the same problem, the structure and function of the Na+,K+-ATPase. We got more space, less administration, and I was free of teaching obligations.

We all got along very well, lived in a relaxed atmosphere, inspiring and helping each other, cooperating, also with the Na+,K+-ATPase colleagues left in the Physiological Institute. And even if we all worked on different sides of the same problem, there were never problems of interfering in each others subjects, or about priority.

In 1988, I retired, kept my office, gave up systematic experimental work and started to work on kinetic models for the overall reaction of the pump on computer. For this I had to learn how to programme, quite interesting, and amazing what you can do with a computer from the point of view of handling even complicated models. And even if my working hours are fewer, being free of all obligations, the time I spent on scientific problems are about the same as before my retirement.

I enjoy no longer having a meeting calendar, I enjoy to go fly-fishing when the weather is right, and enjoy spending a lot of time with my grandchildren.

This autobiography/biography was written at the time of the award and later published in the book series Les Prix Nobel/ Nobel Lectures/The Nobel Prizes. The information is sometimes updated with an addendum submitted by the Laureate.

Jens C. Skou died on 28 May 2018.

For more updated biographical information, see:

Jens Chr. Skou: Lucky Choices. The Story of my Life in Science. U Press, Copenhagen 2016.

Paul D. Boyer – Biographical

The first 21 years of my life were spent in Provo, Utah, then a city of about 15,000 people, beautifully situated at the foot of the Wasatch Mountains. Hardy Mormon pioneers had settled the area only 70 years before my birth in 1918. Provo was a well-designed city with stable neighbourhoods, a pride in its past and a spirit of unbounded opportunity. The geographical isolation and lack of television made world happenings and problems seem remote.

My father, Dell Delos Boyer, born in 1879 in Springville, Utah, came from the Pennsylvania Boyers, who in turn came from an earlier Bayer ancestry in what is now Holland and Germany. A small portion of my Boyer DNA has been traced to John Alden, famous as a Mayflower pilgrim who wooed for another and won for himself. Dad’s education, at what was then the Brigham Young Academy, was delayed by the ill health he had endured in much of his youth. Through his ambition, and the sacrifices of his family, he acquired training in Los Angeles to become an osteopathic physician. He served humanity well. More by example than by word, my father taught me logical reasoning, compassion, love of others, honesty, and discipline applied with understanding. He also taught me such skills such as pitching horseshoes and growing vegetables. Dad loved to travel. Family trips to Yellowstone and to what are now national parks in Southern Utah, driving the primitive roads and cars of that day, were real adventures. Father became a widower when the youngest of my five siblings was only eight. Fifteen years later he married another fine woman. They shared many happy times, and she cared for him during a long illness as he died from prostate cancer at the age of 82. Prostate cancer also took the life of my only brother when he was 76. If our society continues to support basic research on how living organisms function, it is likely that my great grandchildren will be spared the agony of losing family members to most types of cancer.

Recently I scanned notes on a diary that my mother, Grace Guymon, wrote in her late teens, when living near Mancos, Colorado. The Guymons were among the Huguenots who fled religious persecution in France. My French heritage has been mixed with English and other nationalities as the Guymons descended. Mother’s diary revealed to me more about her vitality and charm than I remembered from her later years, which were clouded by Addison’s disease. She died in 1933, at the age of 45, just weeks after my fifteenth birthday. Discoveries about the adrenal hormones, that could have saved her life, came too late. Her death contributed to my later interest in studying biochemistry, an interest that has not been fulfilled in the sense that my accomplishments remain more at the basic than the applied level. Mother made a glorious home environment for my early years. During her long illness and after her death, all of the children helped with family chores. One of my less pleasant memories is of getting up in the middle of the night to use our allotted irrigation time to water the garden.

The large, gracious home provided by Mother and Dad at 346 North University Avenue has been replaced by a pizza parlor, although an inspection a few months ago revealed that the irrigation ditch for our garden area (now a parking lot) can still be found. Mother had a talent for home decorating. I often read from a set of the Book of Knowledge or Harvard Classics while lying in front of the fireplace, with a mantel designed and decorated by her. Staring into the glowing coals as a fire dims provided a wonderful milieu for a youthful imagination. I also remember such things as picnics in Provo Canyon, and the anticipation that I might get to lick the dasher after cranking the ice-cream freezer. My older brother, Roy, and I had a play-fight relationship. I still carry a scar on my nose from when I plunged (he pushed me!) through the mirror of the dining room closet. I am told that I had a bad temper, and remember being banished to the back hall until civility returned. Perhaps this temper was later sublimated into drive and tenacity, traits that may have come in part from my mother.

The great depression of the 1930s left lasting impressions on all our family. Father’s patients became non-paying or often exchanged farm produce or some labor for medical care. Mother saved pennies to pay the taxes. The burden of paper routes and odd jobs to provide my spending money made it painful when my new Iver Johnson bicycle was stolen. We were encouraged to be creative. I recall mother’s tolerance when she allowed me, at an early age, to take off the hinges and doors of cupboards if I would put them back on. My first exposure to chemistry came when I was given a chemistry set for Christmas. It competed for space in our basement with a model electric trains and an “Erector” set. After school the neighborhood yards were filled with shouts of play; games of “kick-the-can,” “run-sheepy-run,” “steal-the-sticks,” as well as marbles, baseball and other activities. In our back yard we built tree houses, dug underground tunnels and secret passages, and made a small club house. The mountains above our house offered other outlets for adventuresome teenage boys. Days were spent in an abandoned cabin or sleeping under the sky in the shadow of Provo peak. We even took cultures of sour dough bread to the mountains and baked delicious biscuits in an a rusty stove. Mountain hikes instilled in me a life-long urge to get to the top of any inviting summit or peak.

Provo public schools were excellent. At Parker Elementary School, a few blocks from my home, I fell in love with my 3rd grade teacher, Miss McKay. Students who learned more easily were allowed to skip a grade, and I entered the new Farrer Junior High school at a younger age than my classmates. This handicapped me in two types of sporting events, athletics and courting girls. Girls did not want to dance with little Paul Boyer; boys were quite unimpressed with my physique. As I grew my status among fellows improved. Once I got into a scuffle in gym class, the instructor had the “combatants” put on boxing gloves, and I gave more than I received. It wasn’t until late high school and early college that I gained enough size and skill to make me welcome on intramural basketball teams.

I was one of about 500 students of Provo High School, where the atmosphere was friendly, and scholarship and activities were encouraged by both students and faculty. I participated on debating teams and in student government, and served as senior class president. I still have a particularly high regard for my chemistry teacher, Rees Bench. I was pleased when he wrote in my Yearbook for graduation, “You have proven yourself as a most outstanding student.” I graduated while still 16, and thought myself quite mature. I wish I had saved a copy of my valedictorian address. I suspect it may have sparkled with naivete.

It was always assumed that I would go to college. The Brigham Young University (BYU) campus was just a few blocks from my home and tuition was minimal. It was a small college of about 3,500 students, less than a tenth of its present size. As in high school, I enjoyed social and student government activities. Friendships abounded. New vistas were opened in a variety of fields of learning. Chemistry and mathematics seemed logical studies to emphasize, although I had little concept as to where they might lead. A painstaking course in qualitative and quantitative analysis by John Wing gave me an appreciation of the need for, and beauty of, accurate measurement. However, the lingering odor of hydrogen sulfide, used for metal identification and separation, called unwanted attention to me in later classes. “Prof” Joe Nichol’s enthusiasm for general chemistry was superbly conveyed to his students. Professor Charles Maw excelled in transferring a knowledge of organic chemistry to his students. Biochemistry was not included in the curriculum.

Summers I worked as a waiter and managerial assistant at Pinecrest Inn, in a canyon near Salt Lake City. One summer a college friend and I lived there in a sheep camp trailer while managing a string of saddle horses for the guests to use. A different type of education came when as a member of a medical corps in the National Guard I spent several weeks in a military camp in California.

As my senior year progressed several career paths were considered; employment as a chemist in the mining industry, a training program in hotel management, the study of osteopathic or conventional medicine, or some type of graduate training. Little information was available about the latter possibility; but a few chemistry majors from BYU had gone on to graduate school. I have a tendency to be lucky and make the right choices based on limited information. A notice was posted of a Wisconsin Alumni Research Foundation (WARF) Scholarship for graduate studies. My application was approved, and the stage was set for a later phase of my career.

Before leaving Provo, a most important and fortunate event occurred. A beautiful and talented brunette coed, with one year of college to finish, indicated a willingness to marry me. She came from a large and loving family, impoverished financially by her father’s death when she was 2 years old. She had worked and charmed her way nearly through college. My savings were limited and hers were negative. But it was clear that my choice was to have her join with me in the Wisconsin adventure or take my chances when I returned a year later. It was an easy decision. Paul, who had just turned 21, and Lyda Whicker, 20, were married in my father’s home on August 31, 1939. Five days later we left by train to Wisconsin for my graduate study.

A few months after our arrival our new marriage almost ended. I was admitted to the student infirmary with diagnosed appendicitis. Through medical mismanagement my appendix ruptured and I became deathly ill. Sulfanilamides, discovered a few years earlier by Domagk, saved my life. Last summer I read an outstanding book, The Forgotten Plague: How the Battle Against Tuberculosis Was Won and Lost, by Frank Ryan. The book gives a stirring account, the first I have read, of Domagk’s research and how he was not allowed to leave Hitler’s Germany to receive the 1939 Nobel Prize.

Fortunately, the Biochemistry Department at the University of Wisconsin in Madison was outstanding and far ahead of most others in the country. A new wing on the biochemistry building had recently been opened. The excitement of vitamins, nutrition and metabolism permeated the environment. Steenbock had recently patented the irradiation of milk for enrichment with vitamin D. Elvehjem’s group had discovered that nicotinic acid would cure pellagra. Petersen’s group was identifying and separating bacterial growth factors. Link’s group was isolating and identifying a vitamin K antagonist from sweet clover. Patents for the use of dicoumarol as a rat poison and as an anticoagulant sweetened the coffers of the WARF, the Foundation that supported my scholarship. Among younger faculty an interest in enzymology and metabolism was blossoming.

Married graduate students were rare, and the continuing economic depression made jobs hard to find. But my remarkable wife soon found a good job, and I settled into graduate studies. During our Wisconsin years she gained a perspective of art while employed in Madison’s leading art retail outlet. It was years later before Lyda finished a college degree, became a professional editor at UCLA, and worked with me on the eighteen-volume series of The Enzymes. Our contacts in graduate school and through Lyda’s employment gave us life-long friends; one was Henry Lardy, from South Dakota farm country. He and I were assigned to work under Professor Paul Phillips. Henry was highly talented, and it was my good fortune to work along side him. Phillips’ main interests were in reproductive and nutritional problems of farm animals. Henry developed an egg yolk medium for sperm storage that revolutionized animal breeding.

We were encouraged by Phillips to explore metabolic and enzyme interests. I did not realize that it was unusual to be able step across the hall and attend a symposium on respiratory enzymes in which such biochemical giants as Otto Meyerhof, Fritz Lipmann, and Carl Cori spoke. Evening research discussion groups with keen young faculty such as Marvin Johnson and Van Potter, centered on enzymes and metabolism, broadened and sharpened our perspectives. One evening I presented my and Henry’s evidence for the first known K+ activation of an enzyme, pyruvate kinase. Henry kept score on the interruptions for questions or discussions-some 35 as I recall. This superb training environment set the base for my career.

My Ph.D. degree was granted in the spring of 1943, the nation was at war, and I headed for a war project at Stanford University. A few weeks after my arrival in California, on my birthday, July 31, our daughter Gail was born. I became somewhat more involved in home duties and more deeply in love with Lyda.

The wartime Committee on Medical Research sponsored a project at Stanford University on blood plasma proteins, under the direction of J. Murray Luck, founder of the nonprofit Annual Review of Biochemistry and other Reviews. Concentrated serum albumin fractionated from blood plasma was effective in battlefield treatment of shock. When heated to kill microorganisms and viruses, the solutions of albumin developed cloudiness from protein denaturation. The principal goal of our research project was to find some way to stabilize the solutions so that they would not show this behavior. Our small group found that acetate gave some stabilization and butyrate was better. This led to the discovery that long chain fatty acids would remarkably stabilize serum albumin to heat denaturation, and would even reverse the denaturation by heat or concentrated urea solutions. Other compounds with hydrophobic portions and a negative charge, such as acetyl tryptophan, were also effective. Our stabilization method was quickly adopted and is still in use. From the Stanford studies I gained experience with proteins and a growing respect for the beauty of their structures.

In marked contrast to the University of Wisconsin, Biochemistry was hardly visible at Stanford in 1945, consisting of only two professors in the chemistry department. The war project at Stanford was essentially completed, and I accepted an offer of an Assistant Professorship at the University of Minnesota, which had a good biochemistry department. But my local War Draft Board in Provo, Utah, had other plans and I became a member of the U.S. Navy. The Navy did not know what to do with me, the war with Japan was nearly over, and I became what is likely the only seaman second-class that has had a nearly private laboratory at the Navy Medical Research Institute in Bethesda, Maryland. In less than a year I returned to civilian life. In the spring of 1946 I, my wife, and now two daughters, Gail and Hali, became Minnesotans. But I had unknowingly acquired a latent California virus to be expressed years later.

Minnesota has generally competent and honest public officials, good support of the schools and cultural amenities, and an excellent state university. It was a fine place to rear a family, and soon our third child, Douglas, was born. A golden era for biochemistry was just starting. The NIH and NSF research grants were expanding at a rate equal to, or even ahead, of the growing number of meritorious applications. The G.I. bill provided financial support that brought excellent and mature graduate students to campus. New insights into metabolism, enzyme action, and protein structure and function were being rapidly acquired.

Housing was almost unavailable in the post war years. Initially we coped with an isolated, rat-infested farm house. In 1950, after my academic competence seemed satisfactorily established, we built a home not far from the St. Paul campus where the Department of Biochemistry was located. I served as contractor, plumber, electrician, finish carpenter etc. My warm memories of this home include looking at a sparkling, snow-covered landscape, while seated at the desk in the bedroom corner that served as my study, and struggling with the interpretation of some puzzling isotope exchanges accompanying an enzyme catalysis. The understanding that developed was rewarding and perhaps one of my best intellectual efforts. However, it did not seem that the approach would give answers to major problems.

During my early years at Minnesota I conducted an evening enzyme seminar. One participant in our lively discussions was a promising graduate student from another department, Bo Malmstrom, who became a renowned scientist in his field, and is now a retired professor from the University of Göteborg. In 1952 my family spent a memorable summer at the Woods Hole Marine Biological Laboratories on Cape Cod. A sabbatical period on a Guggenheim Fellowship in Sweden in 1955 was especially rewarding. There I did research at both the Wenner-Gren Institute of the University of Stockholm with Olov Lindberg and Lars Ernster, and at the Nobel Medical Institute, working with Hugo Theorell‘s group. Professor Theorell received a Nobel Prize that year, exposing us to the splendor and formality of the Nobel festivities.

Along the way, I was gratified to receive the Award in Enzyme Chemistry of the American Chemical Society in 1955. In 1959-60 I served as Chairman of the Biochemistry Section of the American Chemical Society. In 1956 I accepted a Hill Foundation Professorship and moved to the medical school campus of the University of Minnesota in Minneapolis. Much of my group’s research was on enzymes other than the ATP synthase. But solving how oxidative phosphorylation occurred remained one the most challenging problems of biochemistry, and I could not resist its siren call. Mildred Cohn reported that mitochondria doing oxidative phosphorylation catalyzed an exchange of the phosphate and water oxygens, an intriguing capacity. An able physicist and a pioneer in mass spectrometry, Alfred Nier, made gaseous 18O and facilities available to me, and some experiments were run using this heavy isotope of oxygen. However, much of our effort over several years was directed toward attempting to detect a possible phosphorylated intermediate in ATP (adenosine triphosphate) synthesis using 32P as a probe. The combined efforts of some excellent graduate students and postdocs, most of whom went on to rewarding academic careers, culminated in the discovery of a new type of phosphorylated protein, a catalytic intermediate in ATP formation with a phosphoryl group attached to a histidine residue.

By then, time and queries had stimulated the latent California virus. Change was underway. In the summer of 1963, I and a group of graduate students and postdocs who came with me, activated laboratories in the new wing of the chemistry building at the University of California in Los Angeles (UCLA), located on a beautiful campus at the foot of the Santa Monica mountains. We soon found that the enzyme-bound phosphohistidine we had discovered was an intermediate in the substrate level phosphorylation of the citric acid cycle. It was not a key to oxidative phosphorylation. The experience reminds me of a favorite saying: Most of the yield from research efforts comes from the coal that is mined while looking for diamonds.

In 1965 I accepted the Directorship of a newly created Molecular Biology Institute (MBI) at UCLA, in part because of my disappointment that oxidative phosphorylation had resisted our efforts. A building that was promised failed to materialize, but through luck and persistence adequate funds were obtained, partly from private resources, and promising faculty were recruited. The objective was to promote basic research on how living cells function at the molecular level. I believe the best research is accomplished by a faculty member with a small group of graduate students and postdocs, who freely design, competently conduct and intensely evaluate experiments. To spend time with such a group I soon found ways to reduce my administrative chores. Probes of oxidative phosphorylation continued, and, as 1971 approached, we hit pay dirt. We recognized the first main postulate of what was to become the binding change mechanism for ATP synthesis, namely that energy input was not used primarily to form the ATP molecule, but to promote the release of an already formed and tightly bound ATP.

In the following decade, the other two main concepts of the mechanism were revealed, namely that the three catalytic sites participate sequentially and cooperatively, and that our, and other, data could be best explained by what was termed a rotational catalysis. These previously unrecognized concepts in enzymology provided motivation and excitement within my research group. Richard Cross, a postdoctoral fellow trained with Jui Wang at Yale, capably probed tightly bound ATP. Jan Rosing, a gifted experimentalist from Bill Slater’s group in Amsterdam, and Celik Kayalar, an intelligent, innovative graduate student from Turkey, formed a productive pair that unveiled essential facets of cooperative catalysis. David Hackney, a postdoc from Dan Koshland’s stable of budding scientists at Berkeley, was an intellectual leader in our 18O experimentation that led to rotational catalysis. Dan Smith, Michael Gresser, Linda Smith, and Chana Vinkler (from Israel) as postdocs, and Lee Hutton, Gary Rosen and Glenda Choate as graduate students, established the participation of bound intermediates in rapid mixing and quenching experiments, and conducted 18O exchange experiments that clarified and supported our mechanistic postulates.

In ensuing years, other aspects of the complex ATP synthase were explored that solidified our feeling that the binding change mechanism was likely valid and general, and promoted its acceptance in the field. I will resist telling you here about the number, properties, and function of the six nucleotide binding sites, of the probes that agreed with rotational catalysis, of the unraveling of the complex Mg2+ and ADP inhibition, of the generality of the mechanism and other synthase properties revealed by studies with chloroplasts, E. coli, and Kagawa’s thermophilic bacterium. It was a pleasure to work on such problems with Teri Melese, a postdoc who excelled in enthusiasm as well as capability, and Zhixiong Xue, an exceptional graduate student that I first met while leading a biochemical delegation to China, with Raj Kandpal a scholarly postdoc from India, with the productive postdocs John Wise (from Alan Senior’s lab) and Rick Feldman (from David Sigman’s lab), with Janet Wood during her sabbatical, and with June-Mei Zhou and Ziyun Du (on leave from Academia Sinica laboratories in China) as well as Dan Wu, Steven Stroop, and Karen Guerrero as graduate students. Special mention should be made of three excellent Russian researchers, Vladimir Kasho, Yakov Milgrom and Marat Murataliev, from the laboratory of Vladimir Skulachev, a respected leader in bioenergetics. With the latter two I am now writing what will likely be my last paper reporting research results. Other welcome postdocs, visitors, and graduate students at UCLA worked with other problems, including the Na+,K+ -ATPase that Skou first isolated, and the related Ca++ transporting ATPase of the sarcoplasmic reticulum. During these active years it was a pleasure to receive peer recognition in the form of the Rose Award of the American Society for Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, the preeminent society in my field (I served as its President many years earlier).

An unexpected benefit of my career in biochemistry has been travel. The information exchanged and gained at scientific conferences and visits has been tremendously important for progress in my laboratory. My travelophilic wife and I thoroughly enjoyed being guests of the Australian and South African biochemical societies while visiting their countries. Meetings or laboratory visits in Japan, Sweden, France, Germany, Russia, Italy, Wales, Argentina, Iran, and elsewhere gave us a world perspective. Manuscripts that have to be produced, sometimes a bit unwillingly, offer the challenge to present speculation and perspective often not welcome by editors of prestigious journals. It was in a volume from a conference dedicated to one of the giants of the bioenergetics field, Efraim Racker, that the designation “the binding change mechanism” was introduced. Conferences at the University of Wisconsin provided opportunity to publish thoughts about rotational catalysis that had not been enthusiastically endorsed at Gordon Conferences, where information is exchanged without publication. These travels have strong scientific justification. They provided the opportunity for exchange of information, to test new ideas, to gain new perspective, and to avoid unnecessary experiments. The milieu encourages innovation and planning, as well as providing a stimulus and vitality that fosters research progress.

Other events that make up a lifetime continued. Through fortunate circumstances, Lyda and I obtained a building lot at a price that a professor could afford, in the hills north of UCLA, overlooking the city and ocean. The home we built (I was again contractor and miscellaneous laborer) has served as a focal point for family activities, and a temporary residence for grandchildren attending UCLA. The home meant much for my research, as I could readily move between home and lab, and the ambiance created was supportive for study and writing.

The study of life processes has given me a deep appreciation for the marvel of the living cell. The beauty, the design, and the controls honed by years of evolution, and the ability humans have to gain more and more understanding of life, the earth and the universe, are wonderful to contemplate. I firmly believe that our present and future knowledge of all that we are and what surrounds us depends on the tools and approaches of science. I was struck by how well Harold Kroto, one of last year’s Nobelists, presented what are some of my views in his biographical sketch. As he stated, “I am a devout atheist–nothing else makes sense to me and I must admit to being bewildered by those, who in the face of what appears to be so obvious, still believe in a mystical creator.” I wonder if in the United States we will ever reach the day when the man-made concept of a God will not appear on our money, and for political survival must be invoked by those who seek to represent us in our democracy.

It is disappointing how little the understanding that science provides seems to have permeated into society as a whole. All too common attitudes and approaches seem to have progressed little since the days of Galileo. Religious fundamentalists successfully oppose the teaching of evolution, and by this decry the teaching of critical thinking. We humans have a remarkable ability to blind ourselves to unpleasant facts. This applies not only to mystical and religious beliefs, but also to long-term environmental consequences of our actions. If we fail to teach our children the skills they need to think clearly, they will march behind whatever guru wears the shiniest cloak. Our political processes and a host of human interactions are undermined because many have not learned how to gain a sound understanding of what they encounter.

The major problem facing humanity is that of the survival of our selves and our progeny. In my less optimistic moments, I feel that we will continue to decimate the environment that surrounds us, even though we know of our folly and of what has happened to others. Humans could become quite transient occupants of planet earth. The most important cause of our problem is over population, which nature, as with other species, will deal with severely. I hear the cry from capable environmental leaders and organizations for movement toward sustainable societies. They are calling for sensible approaches to steer us away from impending disaster. But their voices remain largely unheard as those with power, and those misled by religious or nationality concerns, become immersed in unimportant, self-centered and short range pursuits.

This autobiography/biography was written at the time of the award and later published in the book series Les Prix Nobel/ Nobel Lectures/The Nobel Prizes. The information is sometimes updated with an addendum submitted by the Laureate.

Paul D. Boyer died on 2 June 2018.

Jens C. Skou – Banquet speech

Jens C. Skou’s speech at the Nobel Banquet, December 10, 1997

Your Majesties, Your Royal Highnesses, Ladies and Gentlemen,

On behalf of Professor Boyer, Dr. Walker and myself, I would like to express how grateful we are for the great honour the Nobel Foundation and the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences has bestowed upon us by awarding us the Nobel Prize in Chemistry.

It is impressive that the Nobel Foundation now for almost hundred years has been able to maintain the Nobel Prize as the most rewarding a scientist can achieve. It cannot only be due to the size of the prize, which is substantial, but also to the thoroughness behind the decisions, and because the prize ceremony is surrounded by such festivity that it attracts worldwide attention.

The Nobel Prizes and the ceremony around the awards puts focus not only on the work done by the Prize-Winners, but arouses in the public a more general interest in science, and gives us scientists a very important opportunity to tell what science is and the importance of science.

The unique prestige connected with the Prize also gives the laureates an unusual opportunity to be heard and thereby influence the public view on science and not least to influence the decision makers for the benefit of science and society.

This is perhaps the most rewarding and important aspect of the Nobel Prizes, and as far as I understand, it is also in agreement with Alfred Nobel’s intentions.

Thank you for giving us this opportunity.

Jens C. Skou – Photo gallery

1 (of 12) Jens C. Skou receiving his Nobel Prize from the hands of His Majesty the King.

Copyright © Pica Pressfoto AB 1997, S-105 17 Stockholm, Sweden, telephone: +46-8-13 52 40 Photo: Anders Wiklund

2 (of 12) Jens C. Skou after receiving his Nobel Prize from H.M. King Carl XVI Gustaf of Sweden at the Stockholm Concert Hall on 10 December 1997.

Nobel Foundation. Photo: Lars Åström

3 (of 12) Chemistry laureates Paul D. Boyer, John E. Walker and Jens C. Skou on stage at the Nobel Prize award ceremony at the Stockholm Concert Hall on 10 December 1997.

Nobel Foundation. Photo: Lars Åström

4 (of 12) 1997 Nobel Prize laureates on the Stockholm Concert Hall stage: From left: physics laureates Steven Chu, Claude Cohen-Tannoudji and William D. Phillips, chemistry laureates Paul D. Boyer, John E. Walker and Jens C. Skou, medicine laureate Stanley B. Prusiner, literature laureate Dario Fo and economic sciences laureates Robert C. Merton and Myron S. Scholes.

Nobel Foundation. Photo: Lars Åström

5 (of 12) All 1997 Nobel Laureates on the Stockholm Concert Hall stage. Jens C. Skou is sixth from left.

© Pressens Bild AB, 1997 S-112 88 Stockholm, Sweden, telephone: +46 (0)8 738 38 00. Photo: Ola Torkelsson

6 (of 12) A view of the Nobel Prize Award Ceremony at the Stockholm Concert Hall, 10 December 1997.

© Pica Pressfoto AB 1997, S-105 17 Stockholm, Sweden, telephone: +46-8-13 52 40. Photo: Ulf Palm

7 (of 12) Jens Skou after at the Nobel Prize award ceremony in Stockholm, Sweden on 10 December 1997.

Photo from the Lars Åström archive

8 (of 12) Chemistry laureates Paul D. Boyer, John E. Walker and Jens C. Skou showing their Nobel Prizes after the award ceremony at the Stockholm Concert Hall on 10 December 1997.

Nobel Foundation. Photo: Lars Åström

9 (of 12) Jens C. Skou delivering his speech of thanks at the Nobel Prize banquet in the Stockholm City Hall, Sweden, on 10 December 1997.

Nobel Foundation. Photo: Lars Åström

10 (of 12) Jens C. Skou delivering his Nobel Lecture on 8 December 1997.

Photo from the Lars Åström archive

11 (of 12) All 1997 laureates assembled at the Swedish Academy in Stockholm Sweden during Nobel Week, December 1997. Back row from left: Chemistry laureate Jens C. Skou, medicine laureate Stanley B. Prusiner, literature laureate Dario Fo, economi sciences laureates Robert C. Merton and Myron S. Scholes. Front row from left: Chemistry laureate John E. Walker, physics laureate William D. Phillips, chemistry laureate Paul D. Boyer and physics laureate Claude Cohen-Tannoudji.

Photo from the Lars Åström archive

12 (of 12) Eight of the 1997 Nobel Prize laureates assembled during Nobel Week, December 1997. Back row from left: Robert C. Merton, Steven Chu, Myron S. Scholes, William D. Phillips and and John E. Walker. Front row from left: Paul D. Boyer, Claude Cohen-Tannoudji and Jens C. Skou

Photo from the Lars Åström archive

Paul D. Boyer – Other resources

Links to other sites

Jens C. Skou – Other resources

Links to other sites

On Jens C. Skou from Aarhus Universitet (in Danish)

On Jens C. Skou ffrom International Union of Chrystallography

Paul D. Boyer – Nobel Lecture

Nobel Lecture, December 8, 1997

Energy, Life, and ATP

Read the Nobel Lecture

Pdf 1.08 MB

Jens C. Skou – Nobel Lecture

Nobel Lecture, December 8, 1997

The Identification of the Sodium-Potassium Pump

Read the Nobel Lecture

Pdf 903 kB

Paul D. Boyer – Photo gallery

1 (of 15) Paul D. Boyer receiving his Nobel Prize from the hands of His Majesty the King.

Copyright © Pica Pressfoto AB 1997, S-105 17 Stockholm, Sweden, telephone: +46-8-13 52 40 Photo: Anders Wiklund

2 (of 15) Paul D. Boyer receiving his Nobel Prize from H.M. King Carl XVI Gustaf of Sweden at the Stockholm Concert Hall on 10 December 1997.

Nobel Foundation. Photo: Lars Åström

3 (of 15) Chemistry laureates Paul D. Boyer, John E. Walker and Jens C. Skou on stage at the Nobel Prize award ceremony at the Stockholm Concert Hall on 10 December 1997.

Nobel Foundation. Photo: Lars Åström

4 (of 15) 1997 Nobel Prize laureates on the Stockholm Concert Hall stage: From left: physics laureates Steven Chu, Claude Cohen-Tannoudji and William D. Phillips, chemistry laureates Paul D. Boyer, John E. Walker and Jens C. Skou, medicine laureate Stanley B. Prusiner, literature laureate Dario Fo and economic sciences laureates Robert C. Merton and Myron S. Scholes.

Nobel Foundation. Photo: Lars Åström

5 (of 15) All 1997 Nobel Laureates on the Stockholm Concert Hall stage. Jens C. Skou is sixth from left.

© Pressens Bild AB, 1997 S-112 88 Stockholm, Sweden, telephone: +46 (0)8 738 38 00. Photo: Ola Torkelsson

6 (of 15) A view of the Nobel Prize Award Ceremony at the Stockholm Concert Hall, 10 December 1997.

© Pica Pressfoto AB 1997, S-105 17 Stockholm, Sweden, telephone: +46-8-13 52 40. Photo: Ulf Palm

7 (of 15) Chemistry laureates Paul D. Boyer, John E. Walker and Jens C. Skou showing their Nobel Prizes after the award ceremony at the Stockholm Concert Hall on 10 December 1997.

Nobel Foundation. Photo: Lars Åström

8 (of 15) Paul D. Boyer at the Nobel Prize banquet in the Stockholm City Hall, Sweden, on 10 December 1997.

Nobel Foundation. Photo: Lars Åström

9 (of 15) Paul D. Boyer on the dance floor at the Nobel Prize banquet in the Stockholm City Hall, Sweden, on 10 December 1997.

Nobel Foundation. Photo: Lars Åström

10 (of 15) Paul D. Boyer delivering his Nobel Lecture at the on 8 December 1997.

Photo from the Lars Åström archive

11 (of 15) Paul D. Boyer delivering his Nobel Prize lecture on 8 December 1997.

Nobel Foundation. Photo: Lars Åström

12 (of 15) Paul D. Boyer during Nobel Week, December 1997.

Photo from the Lars Åström archive

13 (of 15) Steven Chu, Paul D. Boyer and John E. Walker during a press conference at the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences in Stockholm Sweden during Nobel Week, December 1997.

Nobel Foundation. Photo: Lars Åström

14 (of 15) All 1997 laureates assembled at the Swedish Academy in Stockholm Sweden during Nobel Week, December 1997. Back row from left: Chemistry laureate Jens C. Skou, medicine laureate Stanley B. Prusiner, literature laureate Dario Fo, economi sciences laureates Robert C. Merton and Myron S. Scholes. Front row from left: Chemistry laureate John E. Walker, physics laureate William D. Phillips, chemistry laureate Paul D. Boyer and physics laureate Claude Cohen-Tannoudji.

Photo from the Lars Åström archive

15 (of 15) Eight of the 1997 Nobel Prize laureates assembled during Nobel Week, December 1997. Back row from left: Robert C. Merton, Steven Chu, Myron S. Scholes, William D. Phillips and and John E. Walker. Front row from left: Paul D. Boyer, Claude Cohen-Tannoudji and Jens C. Skou

Photo from the Lars Åström archive

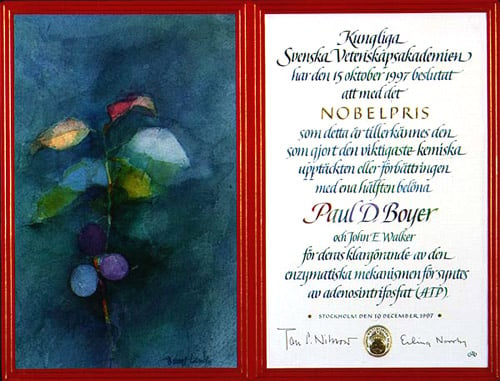

Paul D. Boyer – Nobel diploma

Copyright © The Nobel Foundation 1997

Artist: Bengt Landin

Calligrapher: Annika Rücker