Ahmed Zewail – Photo gallery

Ahmed Zewail receiving his Nobel Prize from His Majesty the King at the Stockholm Concert Hall 1999. Copyright © The Nobel Foundation 1999

Photo: Hans Mehlin

Ahmed Zewail receiving his Nobel Prize from His Majesty the King at the Stockholm Concert Hall 1999. [snippet id="11708"]

Ahmed Zewail after receiving his Nobel Prize

from His Majesty the King at the Stockholm Concert Hall 1999.

Copyright © The Nobel Foundation 1999

Photo: Hans Mehlin

All 1999 Nobel Laureates onstage. Ahmed Zewail is third from left.

Copyright © The Nobel Foundation 1999

Photo: Hans Mehlin

© The Nobel Foundation 1999. Photo: Hans Mehlin

The Prize Award Ceremony at the Stockholm Concert Hall. From left Gerardus 't Hooft, Martinus J.G. Veltman and Ahmed Zewail.

Copyright © The Nobel Foundation 1999

Photo: Hans Mehlin

Princess Lilian of Sweden and Nobel Laureate in Chemistry Ahmed H. Zewail at the Nobel Banquet.

© Scanpix Scandinavia 1999, S-105 17 Stockholm, Sweden, telephone, picture library: +46(0)8135555. Photo: James Adanson

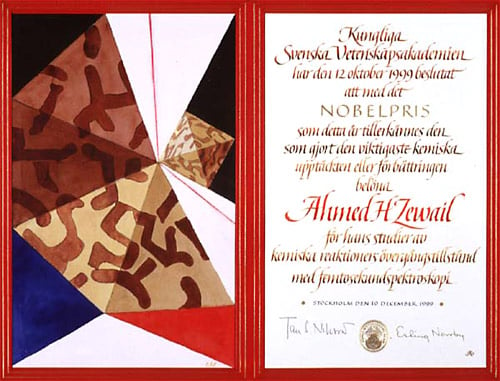

Ahmed Zewail – Nobel diploma

Copyright © The Nobel Foundation 1999

Artist: Nils G Stenqvist

Calligrapher: Annika Rücker

Ahmed Zewail – Nobel Lecture

Ahmed Zewail held his Nobel Lecture December 8, 1999, at Aula Magna, Stockholm University. He was presented by Professor Bengt Nordén, Member of the Nobel Committee for Chemistry.

Read the Nobel Lecture

Pdf 15.43 MB

Ahmed Zewail – Prize presentation

Watch a video clip of the 1999 Nobel Laureate in Chemistry, Ahmed Zewail, receiving his Nobel Prize medal and diploma during the Nobel Prize Award Ceremony at the Concert Hall in Stockholm, Sweden, on 10 December 1999.

Ahmed Zewail – Facts

The Nobel Prize in Chemistry 1999

Ahmed Zewail – Biographical

On the banks of the Nile, the Rosetta branch, I lived an enjoyable childhood in the City of Disuq, which is the home of the famous mosque, Sidi Ibrahim. I was born (February 26, 1946) in nearby Damanhur, the “City of Horus”, only 60 km from Alexandria. In retrospect, it is remarkable that my childhood origins were flanked by two great places – Rosetta, the city where the famous Stone was discovered, and Alexandria, the home of ancient learning. The dawn of my memory begins with my days, at Disuq’s preparatory school. I am the only son in a family of three sisters and two loving parents. My father was liked and respected by the city community – he was helpful, cheerful and very much enjoyed his life. He worked for the government and also had his own business. My mother, a good-natured, contented person, devoted all her life to her children and, in particular, to me. She was central to my “walks of life” with her kindness, total devotion and native intelligence. Although our immediate family is small, the Zewails are well known in Damanhur.

The family’s dream was to see me receive a high degree abroad and to return to become a university professor – on the door to my study room, a sign was placed reading, “Dr. Ahmed,” even though I was still far from becoming a doctor. My father did live to see that day, but a dear uncle did not. Uncle Rizk was special in my boyhood years and I learned much from him – an appreciation for critical analyses, an enjoyment of music, and of intermingling with the masses and intellectuals alike; he was respected for his wisdom, financially well-to-do, and self-educated. Culturally, my interests were focused – reading, music, some sports and playing backgammon. The great singer Um Kulthum (actually named Kawkab Elsharq – a superstar of the East) had a major influence on my appreciation of music. On the first Thursday of each month we listened to Um Kulthum’s concert – “waslats” (three songs) – for more than three hours. During all of my study years in Egypt, the music of this unique figure gave me a special happiness, and her voice was often in the background while I was studying mathematics, chemistry… etc. After three decades I still have the same feeling and passion for her music. In America, the only music I have been able to appreciate on this level is classical, and some jazz. Reading was and still is my real joy.

As a boy it was clear that my inclinations were toward the physical sciences. Mathematics, mechanics, and chemistry were among the fields that gave me a special satisfaction. Social sciences were not as attractive because in those days much emphasis was placed on memorization of subjects, names and the like, and for reasons unknown (to me), my mind kept asking “how” and “why”. This characteristic has persisted from the beginning of my life. In my teens, I recall feeling a thrill when I solved a difficult problem in mechanics, for instance, considering all of the tricky operational forces of a car going uphill or downhill. Even though chemistry required some memorization, I was intrigued by the “mathematics of chemistry”. It provides laboratory phenomena which, as a boy, I wanted to reproduce and understand. In my bedroom I constructed a small apparatus, out of my mother’s oil burner (for making Arabic coffee) and a few glass tubes, in order to see how wood is transformed into a burning gas and a liquid substance. I still remember this vividly, not only for the science, but also for the danger of burning down our house! It is not clear why I developed this attraction to science at such an early stage.

After finishing high school, I applied to universities. In Egypt, you send your application to a central Bureau (Maktab El Tansiq), and according to your grades, you are assigned a university, hopefully on your list of choice. In the sixties, Engineering, Medicine, Pharmacy, and Science were tops. I was admitted to Alexandria University and to the faculty of science. Here, luck played a crucial role because I had little to do with Maktab El Tansiq’s decision, which gave me the career I still love most: science. At the time, I did not know the depth of this feeling, and, if accepted to another faculty, I probably would not have insisted on the faculty of science. But this passion for science became evident on the first day I went to the campus in Maharem Bek with my uncle – I had tears in my eyes as I felt the greatness of the university and the sacredness of its atmosphere. My grades throughout the next four years reflected this special passion. In the first year, I took four courses, mathematics, physics, chemistry, and geology, and my grades were either excellent or very good. Similarly, in the second year I scored very highly (excellent) in Chemistry and was chosen for a group of seven students (called “special chemistry”), an elite science group. I graduated with the highest honors – “Distinction with First Class Honor” – with above 90% in all areas of chemistry. With these scores, i was awarded, as a student, a stipend every month of approximately £13, which was close to that of a university graduate who made £17 at the time!

After graduating with the degree of Bachelor of Science, I was appointed to a University position as a demonstrator (“Moeid”), to carry on research toward a Masters and then a Ph.D. degree, and to teach undergraduates at the University of Alexandria. This was a tenured position, guaranteeing a faculty appointment at the University. In teaching, I was successful to the point that, although not yet a professor, I gave “professorial lectures” to help students after the Professor had given his lecture. Through this experience I discovered an affinity and enjoyment of explaining science and natural phenomena in the clearest and simplest way. The students (500 or more) enriched this sense with the appreciation they expressed. At the age of 21, as a Moeid, I believed that behind every universal phenomenon there must be beauty and simplicity in its description. This belief remains true today.

On the research side, I finished the requirements for a Masters in Science in about eight months. The tool was spectroscopy, and I was excited about developing an understanding of how and why the spectra of certain molecules change with solvents. This is an old subject, but to me it involved a new level of understanding that was quite modern in our department. My research advisors were three: The head of the inorganic section, Professor Tahany Salem and Professors Rafaat Issa and Samir El Ezaby, with whom I worked most closely; they suggested the research problem to me, and this research resulted in several publications. I was ready to think about my Ph.D. research (called “research point”) after one year of being a Moeid. Professors El Ezaby (a graduate of Utah) and Yehia El Tantawy (a graduate of Penn) encouraged me to go abroad to complete my Ph.D. work. All the odds were against my going to America. First, I did not have the connections abroad. Second, the 1967 war had just ended and American stocks in Egypt were at their lowest value, so study missions were only sent to the USSR or Eastern European countries. I had to obtain a scholarship directly from an American University. After corresponding with a dozen universities, the University of Pennsylvania and a few others offered me scholarships, providing the tuition and paying a monthly stipend (some $300). There were still further obstacles against travel to America (“Safer to America”). It took enormous energy to pass the regulatory and bureaucratic barriers.

Arriving in the States, I had the feeling of being thrown into an ocean. The ocean was full of knowledge, culture, and opportunities, and the choice was clear: I could either learn to swim or sink. The culture was foreign, the language was difficult, but my hopes were high. I did not speak or write English fluently, and I did not know much about western culture in general, or American culture in particular. I remember a “cultural incident” that opened my eyes to the new traditions I was experiencing right after settling in Philadelphia. In Egypt, as boys, we used to kid each other by saying “I’ll kill you”, and good friends often said such phrases jokingly. I became friends with a sympathetic American graduate student, and, at one point, jokingly said “I’ll kill you”. I immediately noticed his reserve and coolness, perhaps worrying that a fellow from the Middle East might actually do it!

My presence – as the Egyptian at Penn – was starting to be felt by the professors and students as my scores were high, and I also began a successful course of research. I owe much to my research advisor, Professor Robin Hochstrasser, who was, and still is, a committed scientist and educator. The diverse research problems I worked on, and the collaborations with many able scientists, were both enjoyable and profitable. My publication list was increasing, but just as importantly, I was learning new things literally every day – in chemistry, in physics and in other fields. The atmosphere at the Laboratory for Research on the Structure of Matter (LRSM) was most stimulating and I was enthusiastic about researching in areas that crossed the disciplines of physics and chemistry (sometimes too enthusiastic!). My courses were enjoyable too; I still recall the series 501, 502, 503 and the physics courses I took with the Nobel Laureate, Bob Schrieffer. I was working almost “day and night,” and doing several projects at the same time: The Stark effect of simple molecules; the Zeeman effect of solids like NO2– and benzene; the optical detection of magnetic resonance (ODMR); double resonance techniques, etc. Now, thinking about it, I cannot imagine doing all of this again, but of course then I was “young and innocent”.

The research for my Ph.D. and the requirements for a degree were essentially completed by 1973, when another war erupted in the Middle East. I had strong feelings about returning to Egypt to be a University Professor, even though at the beginning of my years in America my memories of the frustrating bureaucracy encountered at the time of my departure were still vivid. With time, things change, and I recollected all the wonderful years of my childhood and the opportunities Egypt had provided to me. Returning was important to me, but I also knew that Egypt would not be able to provide the scientific atmosphere I had enjoyed in the U.S. A few more years in America would give me and my family two opportunities: First, I could think about another area of research in a different place (while learning to be professorial!). Second, my salary would be higher than that of a graduate student, and we could then buy a big American car that would be so impressive for the new Professor at Alexandria University! I applied for five positions, three in the U.S., one in Germany and one in Holland, and all of them with world-renowned professors. I received five offers and decided on Berkeley.

Early in 1974 we went to Berkeley, excited by the new opportunities. Culturally, moving from Philadelphia to Berkeley was almost as much of a shock as the transition from Alexandria to Philadelphia – Berkeley was a new world! I saw Telegraph Avenue for the first time, and this was sufficient to indicate the difference. I also met many graduate students whose language and behavior I had never seen before, neither in Alexandria, nor in Philadelphia. I interacted well with essentially everybody, and in some cases I guided some graduate students. But I also learned from members of the group. The obstacles did not seem as high as they had when I came to the University of Pennsylvania because culturally and scientifically I was better equipped. Berkeley was a great place for science – the BIG science. In the laboratory, my aim was to utilize the expertise I had gained from my Ph.D. work on the spectroscopy of pairs of molecules, called dimers, and to measure their coherence with the new tools available at Berkeley. Professor Charles Harris was traveling to Holland for an extensive stay, but when he returned to Berkeley we enjoyed discussing science at late hours! His ideas were broad and numerous, and in some cases went beyond the scientific language I was familiar with. Nevertheless, my general direction was established. I immediately saw the importance of the concept of coherence. I decided to tackle the problem, and, in a rather short time, acquired a rigorous theoretical foundation which was new to me. I believe that this transition proved vital in subsequent years of my research.

I wrote two papers with Charles, one theoretical and the other experimental. They were published in Physical Review. These papers were followed by other work, and I extended the concept of coherence to multidimensional systems, publishing my first independently authored paper while at Berkeley. In collaboration with other graduate students, I also published papers on energy transfer in solids. I enjoyed my interactions with the students and professors, and at Berkeley’s popular and well-attended physical chemistry seminars. Charles decided to offer me the IBM Fellowship that was only given to a few in the department. He strongly felt that I should get a job at one of the top universities in America, or at least have the experience of going to the interviews; I am grateful for his belief in me. I only applied to a few places and thought I had no chance at these top universities. During the process, I contacted Egypt, and I also considered the American University in Beirut (AUB). Although I visited some places, nothing was finalized, and I was preparing myself for the return. Meanwhile, I was busy and excited about the new research I was doing. Charles decided to build a picosecond laser, and two of us in the group were involved in this hard and “non-profitable” direction of research (!); I learned a great deal about the principles of lasers and their physics.

During this period, many of the top universities announced new positions, and Charles asked me to apply. I decided to send applications to nearly a dozen places and, at the end, after interviews and enjoyable visits, I was offered an Assistant Professorship at many, including Harvard, Caltech, Chicago, Rice, and Northwestern. My interview at Caltech had gone well, despite the experience of an exhausting two days, visiting each half hour with a different faculty member in chemistry and chemical engineering. The visit was exciting, surprising and memorable. The talks went well and I even received some undeserved praise for style. At one point, I was speaking about what is known as the FVH, picture of coherence, where F stands for Feynman, the famous Caltech physicist and Nobel Laureate. I went to the board to write the name and all of a sudden I was stuck on the spelling. Half way through, I turned to the audience and said, “you know how to spell Feynman”. A big laugh erupted, and the audience thought I was joking – I wasn’t! After receiving several offers, the time had come to make up my mind, but I had not yet heard from Caltech. I called the Head of the Search Committee, now a colleague of mine, and he was lukewarm, encouraging me to accept other offers. However, shortly after this, I was contacted by Caltech with a very attractive offer, asking me to visit with my family. We received the red carpet treatment, and that visit did cost Caltech! I never regretted the decision of accepting the Caltech offer.

My science family came from all over the world, and members were of varied backgrounds, cultures, and abilities. The diversity in this “small world” I worked in daily provided the most stimulating environment, with many challenges and much optimism. Over the years, my research group has had close to 150 graduate students, postdoctoral fellows, and visiting associates. Many of them are now in leading academic, industrial and governmental positions. Working with such minds in a village of science has been the most rewarding experience – Caltech was the right place for me.

My biological children were all “made in America”. I have two daughters, Maha, a Ph.D. student at the University of Texas, Austin, and Amani, a junior at Berkeley, both of whom I am very proud. I met Dema, my wife, by a surprising chance, a fairy tale. In 1988 it was announced that I was a winner of the King Faisal International Prize. In March of 1989, I went to receive the award from Saudi Arabia, and there I met Dema; her father was receiving the same prize in literature. We met in March, got engaged in July and married in September, all of the same year, 1989. Dema has her M.D. from Damascus University, and completed a Master’s degree in Public Health at UCLA. We have two young sons, Nabeel and Hani, and both bring joy and excitement to our life. Dema is a wonderful mother, and is my friend and confidante.

The journey from Egypt to America has been full of surprises. As a Moeid, I was unaware of the Nobel Prize in the way I now see its impact in the West. We used to gather around the TV or read in the newspaper about the recognition of famous Egyptian scientists and writers by the President, and these moments gave me and my friends a real thrill – maybe one day we would be in this position ourselves for achievements in science or literature. Some decades later, when President Mubarak bestowed on me the Order of Merit, first class, and the Grand Collar of the Nile (“Kiladate El Niel”), the highest State honor, it brought these emotional boyhood days back to my memory. I never expected that my portrait, next to the pyramids, would be on a postage stamp or that the school I went to as a boy and the road to Rosetta would be named after me. Certainly, as a youngster in love with science, I had no dreams about the honor of the Nobel Prize.

Since my arrival at Caltech in 1976, our contributions have been recognized by countries around the world. Among the awards and honors are:

| Special Honors |

| King Faisal International Prize in Science (1989). |

| First Linus Pauling Chair, Caltech (1990). |

| Wolf Prize in Chemistry (1993). |

| Order of Merit, first class (Sciences & Arts), from President Mubarak (1995). |

| Robert A. Welch Award in Chemistry (1997). |

| Benjamin Franklin Medal, Franklin Institute, USA (1998). |

| Egypt Postage Stamps, with Portrait (1998); the Fourth Pyramid (1999). |

| Nobel Prize in Chemistry (1999). |

| Grand Collar of the Nile, Highest State Honor, conferred by President Mubarak (1999). |

| Prizes and Awards |

| Alfred P. Sloan Foundation Fellow (1978-1982). |

| Camille and Henry Dreyfus Teacher-Scholar Award (1979-1985). |

| Alexander von Humboldt Award for Senior United States Scientists (1983). |

| National Science Foundation Award for especially creative research (1984; 1988; 1993). |

| Buck-Whitney Medal, American Chemical Society (1985). |

| John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Foundation Fellow (1987). |

| Harrison Howe Award, American Chemical Society (1989). |

| Carl Zeiss International Award, Germany (1992). |

| Earle K. Plyler Prize, American Physical Society (1993). |

| Medal of the Royal Netherlands Academy of Arts and Sciences, Holland (1993). |

| Bonner Chemiepreis, Germany (1994). |

| Herbert P. Broida Prize, American Physical Society (1995). |

| Leonardo Da Vinci Award of Excellence, France (1995). |

| Collége de France Medal, France (1995). |

| Peter Debye Award, American Chemical Society (1996). |

| National Academy of Sciences Award, Chemical Sciences, USA (1996). |

| J.G. Kirkwood Medal, Yale University (1996). |

| Peking University Medal, PU President, Beijing, China (1996). |

| Pittsburgh Spectroscopy Award (1997). |

| First E.B. Wilson Award, American Chemical Society (1997). |

| Linus Pauling Medal Award (1997). |

| Richard C. Tolman Medal Award (1998). |

| William H. Nichols Medal Award (1998). |

| Paul Karrer Gold Medal, University of Zürich, Switzerland (1998). |

| E.O. Lawrence Award, U.S. Government (1998). |

| Merski Award, University of Nebraska (1999). |

| Röntgen Prize, (100th Anniversary of the Discovery of X-rays), Germany (1999). |

| Academies and Societies |

| American Physical Society, Fellow (elected 1982). |

| National Academy of Sciences, USA (elected 1989). |

| Third World Academy of Sciences, Italy (elected 1989). |

| Sigma Xi Society, USA (elected 1992). |

| American Academy of Arts and Sciences (elected 1993). |

| Académie Européenne des Sciences, des Arts et des Lettres, France (elected 1994). |

| American Philosophical Society (elected 1998). |

| Pontifical Academy of Sciences (elected 1999). |

| American Academy of Achievement (elected 1999). |

| Royal Danish Academy of Sciences and Letters (elected 2000) |

| Honorary Degrees |

| Oxford University, UK (1991): M.A., h.c. |

| American University, Cairo, Egypt (1993): D.Sc., h.c. |

| Katholieke Universiteit, Leuven, Belgium (1997): D.Sc., h.c. |

| University of Pennsylvania, USA (1997): D.Sc., h.c. |

| Université de Lausanne, Switzerland (1997): D.Sc., h.c. |

| Swinburne University, Australia (1999): D.U., h.c. |

| Arab Academy for Science & Technology, Egypt (1999): H.D.A.Sc. |

| Alexandria University, Egypt (1999): H.D.Sc. |

| University of New Brunswick, Canada (2000): Doctoris in Scientia, D.Sc., h.c. |

| Universita di Roma “La Sapienza”, Italy (2000): D.Sc., h.c. |

| Université de Liège, Belgium (2000): Doctor honoris causa, D., h.c. |

This autobiography/biography was written at the time of the award and later published in the book series Les Prix Nobel/ Nobel Lectures/The Nobel Prizes. The information is sometimes updated with an addendum submitted by the Laureate.

Addendum, January 2006

After the awarding of the Nobel Prize in 1999, I continued to serve as a faculty member at the California Institute of Technology (Caltech) as the Linus Pauling Chair Professor of Chemistry and Professor of Physics, and the Director of the Physical Biology Center for Ultrafast Science and Technology (UST) and the NSF Laboratory for Molecular Sciences (LMS). Current research is devoted to dynamical chemistry and biology, with a focus on the physics of elementary processes in complex systems. A major research frontier is the new development of “4D ultrafast diffraction and microscopy”, making possible the imaging of transient structures in space and time with atomic-scale resolution.

I have also devoted some time to giving public lectures in order to enhance awareness of the value of knowledge gained from fundamental research, and helping the population of developing countries through the promotion of science and technology for the betterment of society. Because of the unique East-West cultures that I represent, I wrote a book Voyage Through Time – Walks of Life to the Nobel Prize hoping to share the experience, especially with young people, and to remind them that it is possible! This book is in 12 editions and languages, so far.

Since the awarding of the Nobel Prize, the following are some of the awards and honors received:

| Special Honors |

| Postage Stamp, issued by the country of Ghana (2002) |

| Ahmed Zewail Fellowships, University of Pennsylvania (2000–) |

| Highest Order of the State from United Arab Emirates, Sudan, Tunisia, Lebanon (2000–) |

| Ahmed Zewail Prize, American University in Cairo (2001–) |

| Ahmed Zewail Prize for Creativity in the Arts, Opera House, Cairo (2004–) |

| Zewail Foundation for Knowledge and Development, Cairo (2004–) |

| Ahmed Zewail Prizes for Excellence and Leadership, ICTP, Trieste, Italy (2004–) |

| Ahmed Zewail Award for Ultrafast Science and Technology, American Chemical Society (2005–). |

| Prizes and Awards |

| Faye Robiner Award, Ross University School of Medicine, New York (2000) |

| Golden Plate Award, American Academy of Achievement (2000) |

| City of Pisa Medal, City Mayor, Pisa, Italy (2000) |

| Medal of “La Sapienza” (“wisdom”), University of Rome (2000) |

| Médaille de l’Institut du Monde Arabe, Paris, France (2000) |

| Honorary Medal, Universite Du Centre, Monastir, Tunisia (2000) |

| Honorary Medal, City of Monastir, from The Mayor, Tunisia (2000) |

| Distinguished Alumni Award, University of Pennsylvania (2002) |

| G.M. Kosolapoff Award, The American Chemical Society (2002) |

| Distinguished American Service Award, ADC, Washington D.C. (2002) |

| Sir C.V. Raman Award, Kolkata, India (2002) |

| Arab American Award, National Museum, Dearborn, Michigan (2004) |

| Gold Medal (Highest Honor), Burgos University, Burgos, Spain (2004) |

| Grand Gold Medal, Comenius University, Bratislava, Slovak Republic (2005) |

| Academies and Societies |

| American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS), Fellow (elected 2000) |

| Chemical Society of India, Honorary Fellow (elected 2001) |

| Indian Academy of Sciences (elected 2001) |

| The Royal Society of London, Foreign Member (elected 2001) |

| Sydney Sussex College, Honorary Fellow, Cambridge, U.K. (elected 2002) |

| Indian National Science Academy, Foreign Fellow (elected 2002) |

| Korean Academy of Science and Technology, Honorary Foreign Member (elected 2002) |

| African Academy of Sciences, Honorary Fellow (elected 2002) |

| Royal Society of Chemistry, Honorary Fellow, U.K. (elected 2003) |

| Russian Academy of Sciences, Foreign Member (elected 2003) |

| The Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences, Foreign Member (elected 2003) |

| The Royal Academy of Belgium, Foreign Member (elected 2003) |

| St. Catherine’s College, Honorary Fellow, Oxford, U.K. (elected 2004) |

| European Academy of Sciences, Honorary Member, Belgium (elected 2004) |

| The Literary & Historical Society, University College, Honorary Fellow, Dublin, Ireland (elected 2004) |

| The National Society of High School Scholars, Honorary Member Board of Advisors, U.S.A. (elected 2004) |

| Academy of Sciences of Malaysia, Honorary Fellow (elected 2005) |

| French Academy of Sciences, Foreign Member (elected 2005) |

| Honorary Degrees |

| Jadavpur University, India (2001): D.Sc., h.c. |

| Concordia University, Montréal, Canada (2002): LLD, h.c. |

| Heriot-Watt University, Scotland (2002): D.Sc., h.c. |

| Pusan National University, Korea (2003): M.D., h.c. |

| Lund University, Sweden (2003) : D.Ph., h.c. |

| Bogaziçi University, Istanbul, Turkey (2003): D.Sc., h.c. |

| École Normale Supérieure, Paris, France (2003): D.Sc., h.c. |

| Oxford University, United Kingdom (2004): D.Sc., h.c. |

| Peking University, People’s Republic of China (2004): H.D.D. |

| Autonomous University of the State of Mexico, Toluca, Mexico (2004): D., h.c. |

| University of Dublin, Trinity College, Ireland (2004): D.Sc., h.c. |

| Tohoku University, Sendai, Japan (2005): H.D.D. |

| American University of Beirut, Lebanon (2005): D.H.L. |

| University of Buenos Aires, Argentina (2005): D., h.c. |

| National University of Cordoba, Argentina (2005): D., h.c. |

For more updated biographical information, see:

Zewail, Ahmed, Voyage through Time. Walks of Life to the Nobel Prize. American University in Cairo Press, Cairo, 2002.

Ahmed Zewail died on 2 August 2016.

Copyright © The Nobel Foundation 2006

Ahmed Zewail – Banquet speech

Ahmed H. Zewail’s speech at the Nobel Banquet, 10 December 1999.

Your Majesties, Excellencies, Ladies and Gentlemen,

Let me begin with a reflection on a personal story, that of a voyage through time. The medal I received from his Majesty this evening was designed by Erik Lindberg in 1902 to represent Nature in the form of the Goddess Isis – or eesis – the Egyptian Goddess of Motherhood. She emerges from the clouds, holding a cornucopia in her arms and the veil which covers her cold and austere face is held up by the Genius of Science1. Indeed, it is the genius of science which pushed forward the race against time, from the beginning of astronomical calendars six millennia ago in the land of Isis to the femtosecond regime honored tonight for the ultimate achievement in the microcosmos. I began life and education in the same Land of Isis, Egypt, made the scientific unveiling in America, and tonight, I receive this honor in Sweden, with a Nobel Medal which takes me right back to the beginning. This internationalization by the Genius of Science is precisely what Mr. Nobel wished for more than a century ago.

In visionary words, Mr. Nobel summed up the purpose of the Prize: “The conquests of scientific research and its ever expanding field awake in us the hope that microbes – of the soul as well as of the body – will gradually be exterminated and that the only war humanity will wage in future will be war against these microbes”. Mr. Nobel saw clearly what he wished for the world and the value of scientific discovery and advancement. Although there exist in the world today some microbes of the soul, such as discrimination and aggression, science was and still is the core of progress for humanity and the continuity of civilization. From the dawn of history, science has probed the universe of unknowns, searching for the uniting laws of nature. The world applauds your Majesties and the Swedish people for your appreciation, recognition, and celebration of discoveries of the unknown, which, according to Alfred Nobel will “leave the greatest benefit to mankind”. I know of no other country that celebrates intellectual achievements with this class and passion.

To the world, the Nobel Prize has become the crowning honor for two reasons. For scientists, it recognizes their untiring efforts which lead to new fields of discovery, and places them in the annals of history with other notable scientists. For Science, the Prize inspires the people of the world about the importance and value of new discoveries, and in so doing science becomes better appreciated and supported by the public, and, hopefully, by governments. Both of these are noble causes and we thank you. To me, there is a third cause as well.

If the Nobel Prize had existed 6,000 years ago, when Egypt’s civilization began, or even 2,000 years ago, when the famous library and university (museum) at Alexandria were established, Egypt would have scored very highly in many fields. In recent times, however, Egypt and the Arab World, which gave to Science Ibn-Sina (Avicenna), Ibn-Rushd (Averroës), Ibn-Hayan (Geber), Ibn-Haytham (Al Hazen), and others, have had no Prizes in science or medicine. I sincerely hope that this first one will inspire the young generations of developing countries with the knowledge that it is possible to contribute to world science and technology. As expressed eloquently in 1825 by Sir Humphrey Davy: “Fortunately, science, like that nature to which it belongs, is neither limited by time nor by space. It belongs to the world, and is of no country and of no age.” There is a whole world outside the boundaries of the “West” and the “North” and we can all help to make it the microbe-free world of Mr. Nobel. I also hope that the Prize will help the region I came from to focus on the advancement of science, the Science Society, and on dignity and peace for humanity.

Your Majesties, I do not know how to express my own personal feelings and those of my family about this recognition. Behind this recognition, there exists a larger community of femtoscientists all over the world who tonight declare themselves proud. My own science family at Caltech of close to 150 young scientists represents the true army that marched to victory and made the contribution possible; they, too, must be proud of their effort. Personally, I have been enriched by my experiences in Egypt and America, and feel fortunate to have been endowed with a true passion for knowledge. I am grateful that this highest crowning honor comes at a young age when I can, hopefully, enjoy and witness its impact on science and humanity. The honor comes with great responsibilities and new challenges for the future, and I do hope to be able to continue the mission, recalling the thoughtful words of the great scholar, Dr. Taha Hussein:

![]()

which can be paraphrased in the following words: “The end will begin when seekers of knowledge become satisfied with their own achievements.”

Thank you, Your Majesties. Thank you, all who are celebrating science and scientists.

1. The inscription reads: Inventas vitam juvat excoluisse per artes, loosely translated: “And they who bettered life on earth by new found mastery” (literally stated, “inventions enhance life which is beautified through art”).

Ahmed Zewail – Other resources

Links to other sites

‘Ahmed Zewail and Femtochemistry’ from DOE R&D Accomplishments

Ahmed Zewail – Interview

Interview with Professor Ahmed H. Zewail by Professor Sture Forsén, Lund University, and David Dishart, student, 12 December 1999.

Professor Zewail talks about how he started in the field of femtosecond spectroscopy; the future of chemistry (3:51); his current work (5:43); his thoughts concerning femtosecond methods for studies in the living cell (7:15); encouraging students in Egypt to study science (8:34); how it is important to find time for thinking (12:19); how the Nobel Prize has affected his life (13:29); and how the Internet makes us more specialized (14:44).

Interview transcript

Professor Zewail, let me first congratulate you to this year’s Nobel Prize in Chemistry for your pioneering work on femtosecond spectroscopy. Would you like to tell how you got started in this interesting field that you have developed?

Ahmed Zewail: Well, you know, Professor Forsén, you know everybody thinks some times that science is done as a master plan and that somebody like me came from Mars and figured out everything and so on, but that’s really not the way it worked. We started at Caltech asking very simple questions: how do we understand the molecule dynamics or the dynamics of molecules, emotions and so on, molecules but in a coherent fashion. These molecules, there are millions and billions of them in the sample that we want to study, and they are all at random. And there are no relationship among them and we would like to just order them somehow so they all can behave at the end as if they are a single molecule at rejectory.

So in the beginning we were trying to develop new laser techniques to see how these molecules, if we prepare them coherent then study them in a coherent fashion that then we can learn about the intrinsic processes such as how does the energy move in the molecules, how molecules changing their orientation and so on. So we did some of the analogues of the powerful nuclear magnetic resonance techniques which you are very familiar with and used coherent pulses and pulse sequences. But then around 1980 I was asking the question: can we do the same thing in a single isolated molecule, completely isolated from the rest of the world? The environment is not there. So the question of using then a combination of molecular beams and ultra fast lasers came to mind and we started to initiate this research area which I had no idea what’s involved in terms of molecule beams but we had my students and I had to get into this area. And fundamentally we’re thinking about if we now excite an isolated molecule, no collision no /- – -/, that if we excite certain vibration in the molecule how would the energy move into all the other modes in the molecule.

And that was really the beginning of femtochemistry science …

And that was really the beginning of femtochemistry science …There are many theories and many ideas of how this, and the typical one it goes back to your Arrhenius, namely that the energy will go in a random way. But to the pleasant surprise of all of us is that the energy was not randomising on the short time scale. We found actually that the energy goes from this mode to another mode and comes back even though we have millions, we have a whole forest of modes in the molecule, but the molecule is behaving very selectively and coherently and the molecules are very complex that we were studying. And that was really the beginning of femtochemistry science, because it immediately indicated to us that if we can excite molecules and initiate this in molecules on a very short time scale prior to their vibration and rotational and scrambling of energy and everything we should be seeing a whole new world of ordered coherence in them and by -87 we made what the Nobel citation called ‘the breakthrough’. Namely that by so doing we’re able to see the motions of the real atoms inside the molecules and with atomic scale resolution of the dynamics.

Professor Zewail, the resolution at which one can study chemical reactions has been constantly decreasing over the past century. Do you think it will be possible, or is it even necessary to go further, right there in the future field of autochemistry?

Ahmed Zewail: This is a legitimate question actually, because I wrote something about this, but the Nobel citation, which was very well written, actually pointed out that this is hint of the, if you like, there is a Guinness time. The reason for that it’s fundamental. It is not that we have to keep shortening the time. It turns out all molecular and biological systems have speeds of the atoms move inside them, the fastest possible speeds are determined by their molecular vibrations and this speeds is about a kilometre per second. One thousand metre per second, which means that if you have femtosecond time resolution or 10 to the -15 or 10 -14 second you have a distance resolution of about a 10th of an Ångström. That means really that you are now frozen all the chemical or biological structures on that times kill you can’t do any better.

What I think the OCT or sub-femtosecond is going to be important and I suggested this in one review article would be to go into the motion of the electrons. So, who knows it may be that we will see one day how we can localise also the electron just like we did with the nuclei. But I think that will be beyond the realm of chemistry and biology, you will be now addressing issues in physics looking at semi conductors and high energy physics and so on. But that’s … I don’t want to commit myself and then proven to be wrong later but that’s basically what I think about it at this point.

How do you see fusion directions in the studies of chemical and biological phenomena or time is loosen or the aura of femtoseconds, would it be possible to make sort of a snap shots x-ray the fraction in femtoseconds time scales or electron defraction. How do you see the future let’s say the next 10, 15, 20 years?

Ahmed Zewail: I’m glad you asked this question, Professor Forsén, firstly because I thought in my Nobel Lecture I pointed that I was delighted that the Swedish Academy of Science did not quote anything about my current work right now, because the current work that my group is focusing on is actually both the time resolve electrons and possibly x-rays to be able to get the architecture of these molecules, the molecular structures themselves, of very complex biological systems. That’s the ultimate goal. We have succeeded so far to do this defraction type experiment on smaller molecules and look at intermediate transit structure but you can imagine the power of this maybe in 10 years, when we are able to look say at the intermediates of proteins process. Or the motions of some of the DNA structures that we are interested in. The effect of salvation does the hydrophobic forces play a fundamental role in the process of folding. There was just a numerous questions I would like to ask and we really have to look at these snap shots at early times.

Femtochemistry provides really strong possibilities for new drugs, do you think it will ever be possible to study at that level in a living cell, perhaps study enzyme reactions?

Ahmed Zewail: Well. that will be really a fantastic advance. Of course the difficulty usually we get into this at this point in time is that in the cell there are the medium itself and the water and so on but one advantage of the femtosecond time resolution, and we demonstrated this in a number of studies, is that even in liquid type environment same coherence I was talking about and the motions that we see we can actually isolate because the protonation from the solvent is not turned on yet on that timescale. So, some people have started to use actually femtosecond methods to image processes in cells. There has been work on DNA, in fact I’m involved in this with my colleagues at Caltech in the looking at the transport of electrons in DNA. A lot of work has been done on proteins including cytocromoxides and others so, you’ll see a variety of applications in the coming years.

I know that you have been or you have a strong desire to promote science and help young scientist’s in your country of birth, Egypt. What are your plans in this direction? Could you tell something about that?

Human resources are just tremendous in Egypt but we need the science base …

Human resources are just tremendous in Egypt but we need the science base …Ahmed Zewail: Yes, I do feel quite strongly about this that probably one of the things that unfortunately this age now to get a Nobel Prize is to really use part of it to help the young people get excited about science. In the States, in the world at large but also with particular focus on Egypt because I came from Egypt and I owe Egypt a lot to what I am now. And I do feel that there are tremendous amount of talent in Egypt, human resources. Human resources are just tremendous in Egypt but we need the science base, we need the correct science base. How to get these people to interact with each other. When I give a lecture on Egypt there are thousands of people in the lecture hall, so obviously they would like to go to science and they would love to do science, but you really have to get the correct science base in order for them to interact, so we are hoping to have maybe a little Caltech maybe a little /- – -/ do you know that just to start something there that really both Egyptians and colleagues from the western world and so on can interact with each other, give the students the exchange and do science at the frontiers.

I think the Nobel Prize will help you in this respect?

Ahmed Zewail: I think the Nobel Prize helps for a number of reasons. Number one, if I can be frank, there is these people will feel by getting a Nobel Prize that I’m one of them, that it is possible to contribute on the world map of science and technology. That’s not only in the hands of the Swedes and the Americans and the British and so on. That they could if they worked hard and they have the abilities and so on, they can achieve even on the highest level. And the other thing also which I’m hoping for is that the government in Egypt is willing and interested in promoting science and technology and this is an ideal time now to be able to do something.

Are there certain fields of science which you think might be especially well suited to young scientist in Egypt?

Ahmed Zewail: I think in Egypt and all over the world you know, David, there are many books I read talking about the end of science. There are many, many books I’ve read and I think this is quite naïve actually because we all just try to uncover something. But the universe at large is full of questions that we still don’t know anything about and there will be always young people brilliant who are going to make new discoveries. I mean if you think in 1999, now this is an ending year of this millennium and you just think about the world of the very small, thinking about manipulating the atoms and the molecules. Think about the whole world of biological complex sciences. We still don’t understand the way a protein folds the way it does. I mean it’s an amazing thing. So, all of this is opened up, you go to the very big, you go to astronomy, we still don’t understand how the big bang and evolving all the way to the human species and so on. So all of this is going to be a very, very exciting to the new people. But for me to sit down here, even as a Nobel Laureate and make a prediction about which science I think that will be a mistake.

Scientists are supposed to be creative and surely they certainly are and you were a most creative man. What are your best creative moments, is it in the shower when you are listening to music in the early mornings can you say something about that?

Ahmed Zewail: Yes, it’s a crazy actually moments you just never know. Well, one of the things I enjoy most is to be left alone with a book. I am not one of the new media experts working all the time with my computers and the PowerPoint’s and things of that sort. So, I’m an old fashioned still in this regard but these are the moment where I really can be creative, if I am, to be left alone with just a book and piece of paper and to be thinking. And I think actually one of the messages to the young people building on David’s question, is the internet and all this wonderful thing we have, these are not thinking machines. These are information gathering, but you should have some time to think and that’s very important.

Nobel Laureates usually complain that getting the Nobel Prize perturbs their life infinitely and how do you try to get away from, to find your sort of precious moments or creativity in the future?

… then he made a very famous statement, something to the effect that this is the last 20 minutes of peace of your life. And he was right …

… then he made a very famous statement, something to the effect that this is the last 20 minutes of peace of your life. And he was right …Ahmed Zewail: Well, I’ll tell you a story and I’ll tell you how I’m trying to do it. When they called me with the Nobel call from Secretary General of the Swedish Academy it was twenty minutes to six and he said well that was well hope I’m not disturbing you but I am the Secretary General of the Swedish Academy. Of course you can imagine I was frozen in time when he said that but then he made a very famous statement, something to the effect that this is the last 20 minutes of peace of your life. And he was right at six o’clock exactly until today I just have not had the time to be in equilibrium with myself. We receive thousands of e-mails and faxes and so on. But I want to really focus on doing this two things I really would like to focus on science and the excitement of science and to help with science. So, that’s my intention to focus my efforts there and I hope I will be able to do so.

Back to your previous answer going to the internet, there’s a lot of talk about information overload that there’s so much information flowing out especially with computers and things that people get sort of too much and can’t think any longer. Do you think that that could be a problem for scientists that it could eventually even become detrimental that there so much information that it becomes difficult to sort of concentrate on a specific area?

Ahmed Zewail: Yes, I do have a concern however, humanity has a great way of adapting and I’m sure scientists of the future, probably after I leave this planet, earth will have a new way of dealing with the internet but I do have a concern in the transition period, namely that … I’ll give you an example, when I was a graduate student and we get a journal, let’s say in your case molecular biology or if you’re not chemical physics or something. You know we are dying to take the whole journal and find out the different areas of science. Professor Forsén is aware of many areas that going on in from physical chemistry to molecular biology but because of the internet nowadays people are getting more and more specialised and so you found that I found with my students they don’t necessarily look at journals any more, but they print right away from the internet what’s relevant to what’s he doing you see. Yes and you’re probably a living example.

I’m guilty I’ll say.

Ahmed Zewail: So there is a danger one has to really be knowing much more because you can’t be too narrow on science.

We have actually received a question from Egypt from a student at the American University in Cairo and he says Sir, addressing you, in your judgment, who was the best chemist, physicist, biologist in this millennium?

Ahmed Zewail: Millennium, yes, not century, well I think that’s a million dollar type question. But I would like to tell this young person who’s asking the question from the American University in Cairo, is that in science doesn’t work this way. Scientists contribute in a variety of ways and I don’t think I can singular one even including Einstein, that I can say that he’s the best. We don’t work like the best basketball player and the best musician and so on. Science is a collective effort. I built on the efforts of a previous scientist, others will build on the work I’m doing and if I look at the whole scope from chemistry to biology to physics, it’s just the list is too long to mention just one and it’s not fair to the others.

I see that our time is drawing to a close here, your 30 minutes and I would like to thank you very much Professor Zewail for coming in and letting us interview you in these nice conditions. Thank you very much.

Ahmed Zewail: Thank you so much.

Did you find any typos in this text? We would appreciate your assistance in identifying any errors and to let us know. Thank you for taking the time to report the errors by sending us an e-mail.