Popular information

English

Swedish

The Nobel Prize in Chemistry 2000

We are used to the great impact scientific discoveries have on our ways of thinking. This year’s Nobel Prize in Chemistry is no exception. What we have been taught about plastic is that it is a good insulator – otherwise we should not use it as insulation in electric wires. But now the time has come when we have to change our views. Plastic can indeed, under certain circumstances, be made to behave very like a metal – a discovery for which Alan J. Heeger, Alan G. MacDiarmid and Hideki Shirakawa are to receive the Nobel Prize in Chemistry 2000.

How can plastic become conductive?

Plastics are polymers, molecules that form long chains, repeating themselves like pearls in a necklace. In becoming electrically conductive, a polymer has to imitate a metal, that is, its electrons need to be free to move and not bound to the atoms. The first condition for this is that the polymer consists of alternating single and double bonds, called conjugated double bonds. Polyacetylene, prepared through polymerization of the hydrocarbon acetylene, has such a structure:

|

| Polyacetylene |

However, it is not enough to have conjugated double bonds. To become electrically conductive, the plastic has to be disturbed – either by removing electrons from (oxidation), or inserting them into (reduction), the material. The process is known as doping.

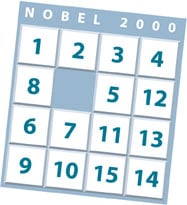

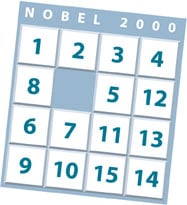

The game in the illustration to the right offers a simple model of a doped polymer. The pieces cannot move unless there is at least one empty “hole”. In the polymer each piece is an electron that jumps to a hole vacated by another one. This creates a movement along the molecule – an electric current.

This model is greatly over-simplified, and we shall consider a more “chemical” model later.

High resolution(JPEG 155 kb)

What Heeger, MacDiarmid and Shirakawa found was that a thin film of polyacetylene could be oxidised with iodine vapour, increasing its electrical conductivity a billion times. This sensational finding was the result of their impressive work, but also of coincidences and accidental circumstances. Let us, shortly, tell the story of one of the great chemical discoveries of our time.

How polymer conductivity was revealed – and the importance of a coffee-break

The leading actor in this story is the hydrocarbon polyacetylene, a flat molecule with an angle of 120° between the bonds and hence existing in two different forms, the isomers cis-polyacetylene and trans-polyacetylene (the latter form illustrated above). At the beginning of the 1970s, the Japanese chemist Shirakawa found that it was possible to synthetisize polyacetylene in a new way, in which he could control the proportions of cis– and trans-isomers in the black polyacetylene film that appeared on the inside of the reaction vessel. Once – by mistake – a thousand-fold too much catalyst was added. To Shirakawa’s surprise, this time a beautiful silvery film appeared.

Shirakawa was stimulated by this discovery. The silvery film was trans-polyacetylene, and the corresponding reaction at another temperature gave a copper-coloured film instead. The latter film appeared to consist of almost pure cis-polyacetylene. This way of varying temperature and concentration of catalyst was to become decisive for the development ahead.

In another part of the world, chemist MacDiarmid and physicist Heeger were experimenting with a metallic-looking film of the inorganic polymer sulphur nitride, (SN)x. MacDiarmid referred to this at a seminar in Tokyo. Here the story could have come to a sudden end, had not Shirakawa and MacDiarmid happened to meet, accidentally, during a coffee-break.

When MacDiarmid heard about Shirakawa’s discovery of an organic polymer that also gleamed like silver, he invited Shirakawa to the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia. They set about modifying polyacetylene by oxidation with iodine vapour. Shirakawa knew that the optical properties changed in the oxidation process and MacDiarmid suggested that they ask Heeger to have a look at the films. One of Heeger’s students measured the conductivity of the iodine-doped trans-polyacetylene and – eureka! The conductivity had increased ten million times!

In the summer of 1977, Heeger, MacDiarmid, Shirakawa, and co-workers, published their discovery in the article “Synthesis of electrically conducting organic polymers: Halogen derivatives of polyacetylene (CH)n” in The Journal of Chemical Society, Chemical Communications. The discovery was considered a major breakthrough. Since then the field has grown immensely, and also given rise to many new and exciting applications. We shall return to some of them.

Doping – for better molecule performance

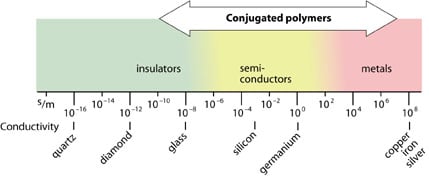

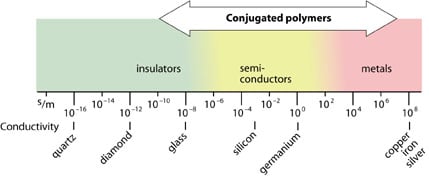

What exactly happened in the polyacetylene films? When we compare some common compounds with regard to conductivity, we see that the conductivities of the polymers vary considerably. Doped polyacetylene is, e.g., comparable to good conductors such as copper and silver, whereas in its original form it is a semiconductor.

|

A metal wire conducts electric current because the electrons in the metal are free to move. How then do we explain the conductivity of the doped polymers?

When describing polymer molecules we distinguish between ![]() (sigma) bonds and

(sigma) bonds and ![]() (pi) bonds. The

(pi) bonds. The ![]() bonds are fixed and immobile. They form the covalent bonds between the carbon atoms. The

bonds are fixed and immobile. They form the covalent bonds between the carbon atoms. The ![]() electrons in a conjugated double bond system are also relatively localised, though not as strongly bound as the

electrons in a conjugated double bond system are also relatively localised, though not as strongly bound as the ![]() electrons. Before a current can flow along the molecule one or more electrons have to be removed or inserted. If an electrical field is then applied, the electrons constituting the

electrons. Before a current can flow along the molecule one or more electrons have to be removed or inserted. If an electrical field is then applied, the electrons constituting the ![]() bonds can move rapidly along the molecule chain. The conductivity of the plastic material, which consists of many polymer chains, will be limited by the fact that the electrons have to “jump” from one molecule to the next. Hence, the chains have to be well packed in ordered rows.

bonds can move rapidly along the molecule chain. The conductivity of the plastic material, which consists of many polymer chains, will be limited by the fact that the electrons have to “jump” from one molecule to the next. Hence, the chains have to be well packed in ordered rows.

As mentioned earlier, there are two types of doping, oxidation or reduction. In the case of polyacetylene the reactions are written like this:

Oxidation with halogen (p-doping): [CH]n + 3x/2 I2 –> [CH]nx+ + x I3–

Reduction with alkali metal (n-doping): [CH]n + x Na –> [CH]nx- + x Na+

The doped polymer is a salt. However, it is not the iodide or sodium ions that move to create the current, but the electrons from the conjugated double bonds. Furthermore, if a strong enough electrical field is applied, the iodide and sodium ions can move either towards or away from the polymer. This means that the direction of the doping reaction can be controlled and the conductive polymer can easily be switched on or off.

Polarons – doped carbon chains

In the first of the above reactions, oxidation, the iodine molecule attracts an electron from the polyacetylene chain and becomes I3– . The polyacetylene molecule, now positively charged, is termed a radical cation, or polaron (fig. b below).

The lonely electron of the double bond, from which an electron was removed, can move easily. As a consequence, the double bond successively moves along the molecule. The positive charge, on the other hand, is fixed by electrostatic attraction to the iodide ion, which does not move so readily. If the polyacetylene chain is heavily oxidised, polarons condense pair-wise into so-called solitons. These solitons are then responsible, in complicated ways, for the transport of charges along the polymer chains, as well as from chain to chain on a macroscopic scale.

We have only touched upon the complex theory that explains how polymers can be made electrically conductive. We recommend the longer, and more detailed, version “Information (advanced) on the Nobel Prize 2000” for everybody who feels challenged to go deeper into the subject.

Brilliant applications

Metal wires that conduct electricity can be made to light up when a strong enough current is passing – as we are reminded of every time we switch on a light bulb. Polymers can also be made to light up, but by another principle, namely electroluminescence, which is used in photodiodes. These photodiodes are, in principal, more energy saving and generate less heat than light bulbs.

In electroluminescence, light is emitted from a thin layer of the polymer when excited by an electrical field. In photodiodes inorganic semiconductors such as gallium phosphide are traditionally used, but now one can also use semiconductive polymers.

Electroluminescence from semiconductive polymers has been known for about ten years. Today there is extensive commercial interest in photodiodes and in light-emitting diodes (LEDs). A LED can consist of a conductive polymer as an electrode on one side, then a semiconductive polymer in the middle and, at the other end, a thin metal foil as electrode. When a voltage is applied between the electrodes, the semiconductive polymer will start emitting light.

|

| High resolution (JPEG 174 kb) |

There are many applications of this brilliant plastic. In a few years, for example, flat television screens based on LED film will become reality, as will luminous traffic signs and information signs. Since it is relatively simple to produce large, thin layers of plastic, one can also imagine light-emitting wallpaper in our homes, and other spectacular things.

More applications

Some applications of conductive polymers that have come onto the market, or are undergoing trials, are:

- Polythiophene derivates, that are of great commercial use in antistatic treatment of photographic film. They can also be used in devices in supermarkets for marking products. The checkouts will then automatically register what the customer has in the trolley.

- Doped polyaniline in antistatic material, e.g. in plastic carpets for offices and operating theatres, where it is important to avoid static electricity. It is also used on computer screens, protecting the user from electromagnetic radiation, and as a corrosion inhibitor.

- Materials such as polyphenylenevinylene may soon be used in mobile phone displays.

- Polydialkylfluorenes are used in the development of new colour screens for video and TV.

With plastic into the future

In the 20th century we had telephones of Bakelite, stockings of nylon, bags of polythene and thousands of other more or less essential plastic objects. What does our new century offer? Perhaps we will use plastics differently now, in the light of this year’s Nobel Prize in Chemistry.

One reason for the great commercial potential of conductive and semiconductive polymers is that they can be produced quickly and cheaply. Electronic components based on polymers, and polymer-based integrated circuits, will soon find their place in consumer products where low processing costs will be more important than high speed.

The step from polymer-based electronics to real molecular-scale electronics is a large but fascinating one. Molecule-based integrated circuits could be reduced to a scale many orders of magnitudes smaller than silicon-based electronics allows. While many challenges lie ahead, we stand at the threshold to a plastic-electronics revolution with exciting implications in chemistry and physics as well as information technology.

The Laureates

Alan J. Heeger (born 1936) received his Ph.D. at University of California, Berkeley 1961 and became associate professor at University of Pennsylvania 1962 and had a professorship there between 1967 and 1982. Since 1982 he is a Professor of Physics at University of California at Santa Barbara and director for the Institute for Polymers and Organic Solids. In 1990 he founded UNIAX Corporation where he is Chair of the Board.

Prof. Alan J. Heeger

Institute for Polymers and Organic Solids

And Department of Physics and Materials

University of California at Santa Barbara

Santa Barbara, CA 93106-5090

Alan G. MacDiarmid (born 1927) grew up in New Zealand, and received his Ph.D. at University of Wisconsin 1953 and at University of Cambridge, UK, 1955. He was associate professor at University of Pennsylvania 1956 and received a professorship there 1964. Since 1988 he is Blanchard Professor of Chemistry.

Prof. Alan G. MacDiarmid

University of Pennsylvania

34th and Spruce Streets

Philadelphia, PA 19104

Hideki Shirakawa (born 1936) received his Ph.D. at Tokyo Institute of Technology 1966 became associate professor at the Institute of Materials Science at University of Tsukuba 1966. He is a Professor there since 1982.

Prof. Hideki Shirakawa

Institute of Materials Sciences

University of Tsukuba

Sakura-mura, Ibaraki 305, Japan

Nobelpriset i kemi 2000 – Populärvetenskaplig information

English

Swedish

Populärvetenskaplig information

10 oktober 2000

Vi har fått vänja oss vid att stora vetenskapliga upptäckter förändrar vårt sätt att tänka. Årets Nobelpris i kemi är inget undantag. Det vi lärt oss om plast är att det är en god isolator – ja, varför skulle den annars användas som isolering i elsladdar? Men nu är det alltså dags att tänka om. Plast kan faktiskt under vissa betingelser fås att uppföra sig nästan som en metall – en upptäckt som belönar Alan J. Heeger, Alan G. MacDiarmid och Hideki Shirakawa med Nobelpriset i kemi för år 2000.

Hur kan plaster leda ström?

Plaster är polymerer, molekyler i form av långa kedjor som upprepar sig likt pärlorna i ett pärlhalsband. För att en polymer ska kunna bli elektriskt ledande, krävs att den “härmar” metallerna, dvs. att elektronerna inte är fast bundna till atomerna utan fritt rörliga. En första förutsättning för detta är att polymeren består av omväxlande enkel- och dubbelbindningar, s.k. konjugerade dubbelbindningar. Polyacetylen, bildad genom polymerisation av kolvätet acetylen (etyn), uppvisar just en sådan struktur.

|

| Polyacetylene |

Det räcker dock inte med de konjugerade dubbelbindningarna. För att plasten ska bli elektriskt ledande måste dess stabilitet rubbas, genom att antingen elektroner rycks ut (oxidation) eller förs in (reduktion) i materialet. Processen har kommit att kallas dopning.

En dopad polymer kan liknas vid ett 15-spel. För att man ska kunna flytta brickorna måste där finnas minst ett “hål”, en plats där en bricka saknas. I polymeren är brickorna elektroner, som en efter en tar hålets plats och bildar en rörelse genom molekylen – en elektrisk ström.

Liknelsen med 15-spelet är en mycket enkel modell av vad som försiggår i molekylerna. Vi återkommer senare med en mer kemisk modell.

High resolution (JPEG 155 kb)

Det Heeger, MacDiarmid och Shirakawa fann var att om de oxiderade en tunn film av polyacetylen med jodånga så ökade den elektriska ledningsförmågan, konduktiviteten, en miljard gånger.

Denna sensationella upptäckt var resultatet av tre forskares imponerande arbete, men också av en rad tillfälligheter. Låt oss, helt kort, berätta historien bakom en av vår tids stora kemiupptäckter.

Om hur konduktiviteten upptäcktes – och vikten av en fikapaus

Huvudaktören i den här historien är kolvätet polyacetylen, en plan molekyl med 120° vinkel mellan bindningarna och som därför förekommer i två olika former, s.k. isomerer, nämligen cis-polyacetylen och trans-polyacetylen (den senare formen visades på förra sidan). I början av 1970-talet gjorde den japanske kemisten Shirakawa en viktig upptäckt. Han fann att man kunde syntetisera polyacetylen på ett nytt sätt, som innebar att han kunde kontrollera andelen cis– och trans-former i den svarta film av polyacetylen som bildades på väggarna i reaktionskärlet. Av ett misstag tillsattes vid ett tillfälle tusen gånger mer katalysator än brukligt. Till Shirakawas förvåning bildades då en vacker silverglänsande film på kärlets väggar.

Shirakawa sporrades av denna upptäckt. Den silverglänsande filmen bestod av trans-polyacetylen och motsvarande reaktion vid en annan temperatur gav i stället en kopparfärgad film. Den senare visade sig innehålla nästan ren cis-polyacetylen. Att på detta sätt variera temperatur och koncentration av katalysator skulle komma att bli av avgörande betydelse för den fortsatta utvecklingen.

I en annan del av världen experimenterade kemisten MacDiarmid och fysikern Heeger med en metallglänsande film av den oorganiska polymeren svavelnitrid, (SN)x. MacDiarmid berättade om detta vid ett seminarium i Tokyo. Här kunde vår historia fått ett snopet slut om inte Shirakawa och MacDiarmid råkat träffas under en kaffepaus.

Då MacDiarmid fick höra om Shirakawas upptäckt av en organisk polymer som också glänste som silver, bjöd han Shirakawa att gästforska vid University of Pennsylvania i Philadelphia. De satte igång att modifiera polyacetylen genom oxidation med jodånga. Shirakawa visste att filmens optiska egenskaper ändrades vid oxidationen och MacDiarmid föreslog att man skulle be Heeger ta en titt på filmerna. Heeger lät en student mäta konduktiviteten hos den jod-dopade trans-polyacetylenen och – heureka! Ledningsförmågan hade ökat tio miljoner gånger!

Sommaren 1977 publicerade Heeger, MacDiarmid och Shirakawa sin upptäckt tillsammans med några medarbetare i artikeln “Synthesis of electrically conducting organic polymers: Halogen derivatives of polyacetylene (CH)n” i tidskriften The Journal of Chemical Society, Chemical Communications. Upptäckten betraktades som ett stort genombrott. Sedan dess har forskningsfältet vuxit enormt och dessutom gett upphov till många nya och spännande tillämpningar – vi kommer till några av dessa längre fram.

Dopning – för att molekylen ska prestera bättre

Vad var det egentligen som hände i de tre forskarnas polyacetylen-filmer? Om vi jämför några vanliga ämnen med avseende på ledningsförmåga, ser vi att polymerernas konduktivitet varierar högst betydligt. “Dopad” polyacetylen är t.ex. jämförbar med goda ledare som koppar och silver, medan dess ursprungsform är en halvledare.

|

En metalltråd leder ström på grund av att elektronerna i metallen är lättrörliga. Hur förklarar man då konduktiviteten hos de dopade polymererna?

När man beskriver molekyler skiljer man mellan ![]() -(sigma) och

-(sigma) och ![]() -(pi) bindningar.

-(pi) bindningar. ![]() -bindningarna är fasta och orörliga. De bygger upp de kovalenta bindningarna mellan kolatomerna.

-bindningarna är fasta och orörliga. De bygger upp de kovalenta bindningarna mellan kolatomerna. ![]() -elektronerna i ett konjugerat dubbelbindningssystem är också relativt lokaliserade, men inte så starkt bundna som

-elektronerna i ett konjugerat dubbelbindningssystem är också relativt lokaliserade, men inte så starkt bundna som ![]() -elektronerna. För att ström ska kunna ledas längs molekylen krävs att någon eller några elektroner antingen avlägsnas eller förs in i molekylen. Om man därefter lägger på ett elektriskt fält kan de elektroner som bygger upp

-elektronerna. För att ström ska kunna ledas längs molekylen krävs att någon eller några elektroner antingen avlägsnas eller förs in i molekylen. Om man därefter lägger på ett elektriskt fält kan de elektroner som bygger upp ![]() -bindningarna snabbt röra sig längs molekylen. Konduktiviteten i plastmaterialet, som består av många polymerkedjor, kommer dock att begränsas av att elektronerna måste “hoppa” från en molekyl till nästa. Därför måste också kedjorna ligga packade i välordnade rader.

-bindningarna snabbt röra sig längs molekylen. Konduktiviteten i plastmaterialet, som består av många polymerkedjor, kommer dock att begränsas av att elektronerna måste “hoppa” från en molekyl till nästa. Därför måste också kedjorna ligga packade i välordnade rader.

Som vi tidigare nämnt, kan två olika typer av dopning förekomma, oxidation eller reduktion. För polyacetylen ser reaktionerna ut så här:

Oxidation med halogen (p-dopning): [CH]n + 3x/2 I2 –> [CH]nx+ + x I3–

Reduktion med alkalimetall (n-dopning): [CH]n + x Na –> [CH]nx- + x Na+

Den dopade polymeren är alltså ett salt. Det är dock inte jodid- resp. natriumjonerna som rör sig för att generera en ström, utan elektronerna i polymerens konjugerade dubbelbindnings-system. Om man lägger på ett tillräckligt starkt elektriskt fält kan man dessutom få jodid- resp. natriumjonerna att antingen närma eller fjärma sig från polymeren, vilket gör att man kan styra i vilken riktning man vill att dopningsreaktionen ska gå. På så sätt kan den ledande polymeren enkelt “sättas på” och “stängas av”.

Polaroner – dopade kolkedjor

I den övre av reaktionerna ovan, oxidationen, drar alltså jodmolekylen till sig en elektron ur polyacetylenkedjan och bildar I3– . Den nu plus-laddade polyacetylenmolekylen bildar en s.k. radikalkatjon eller polaron (b i figuren nedan).

Den ensamma elektronen kan lätt flytta sig. Det får till följd att dubbelbindningen successivt rör sig längs molekylen. Plusladdningen däremot, är låst vid jodidjonen, som inte gärna flyttar på sig. Om man oxiderar polyacetylenkedjan kraftigt bildar polaronerna parvis så kallade solitoner. Solitonerna svarar sedan, på olika sätt, både för transporten av laddning längs polymerkedjorna och för laddningsöverföringen mellan dem på en makroskopisk skala.

Detta var ett försök att snudda vid den komplexa teori som kan förklara hur polymerer kan fås att leda ström. Vi hänvisar till den längre artikeln Advanced Information för den som vill ge sig i kast med änga djupare i ämnet.

Lysande tillämpningar

Metalltrådar som leder ström kan fås att lysa om de görs tillräckligt tunna, det påminns vi om varje gång vi tänder en glödlampa. Polymerer kan också fås att lysa, dock enligt en annan princip, elektroluminicens, vilket man utnyttjar i lysdioder. Dessa lysdioder blir i princip både energisnålare och mindre värmeutvecklande än glödlampor.

Med elektroluminicens menar man att ljus sänds ut från ett tunt skikt av polymeren när den exciteras av ett elektriskt fält. I lysdioder används traditionellt oorganiska halvledare som galliumfosfid, men nu kan man alltså även utgå från halvledande polymerer.

Elektroluminiscens från halvledande polymerer har man känt till i ungefär tio år. Stora kommersiella intressen riktas idag både mot fotodioder och ljusemitterande dioder (LED). En LED kan bestå av en ledande polymer som elektrod på ena sidan, sedan en halvledande polymer i mitten och slutligen en tunn metallfolie som elektrod på andra sidan. Då man lägger på en spänning mellan elektroderna kommer den halvledande polymeren att börja lysa.

|

| Högupplöst bild (JPEG 174 kb) |

Denna lysande plast har många tillämpningar. Om några år kan t.ex. platta TV-skärmar baserade på LED-filmer bli verklighet, liksom lysande trafik- och informationsskyltar. Eftersom det är relativt enkelt att framställa stora, tunna skikt av plast kan man också tänka sig lysande tapeter som belysning i hemmen, och annat spektakulärt.

Fler tillämpningar

Några tillämpningar av ledande polymerer, som lett till produkter på marknaden (eller är under prövning):

- Polytiofen-derivat har stor kommersiell användning i antistatbehandling av fotografisk film, men kan också snart få andra användningsområden, t.ex. för märkning av varor i mataffärerna. I stället för att plocka varorna ur kundvagnen, registrerar kassorna automatiskt köpet när man går ut.

- Dopad polyanilin används som antistatiskt material, t.ex. i plastmattor på kontor och i operationssalar där man vill undvika statisk elektricitet, som skärmskydd mot datorernas elektromagnetiska strålning samt i rostskyddsfärg.

- Material som polyfenylenvinylen kan inom kort få användning i mobiltelefon-displayer.

- Polydialkylfluorener används i framtagningen av nya färgskärmar för video och TV.

Med plasten mot framtiden

Under 1900-talet fick vi telefoner av bakelit, strumpor av nylon, påsar av polyeten och tusentals andra mer eller mindre nödvändiga plastprylar. Vad ska vårt nya århundrade ha att bjuda? Kanske kommer vi att använda plasten på ett annat sätt än tidigare, inte minst mot bakgrund av årets Nobelpris i kemi.

En anledning till det stora kommersiella intresset för ledande polymerer idag är att de kan produceras snabbt och billigt. Polymerbaserade integrerade kretsar kommer snart att finnas i kommersiella produkter där låga fabrikationskostnader är viktigare än komponenternas snabbhet.

Steget från polymerbaserad elektronik till elektronik på molekylärnivå är stort men fantasieggande. Integrerade kretsar baserade på enskilda molekyler skulle innebära att kretsarna krympte många storleksordningar jämfört med dagens kiselbaserade.

Vi står onekligen på tröskeln till en plastelektronikrevolution med många spännande konsekvenser för kemin och fysiken såväl som för informationsteknologin.

Pristagarna

Alan J. Heeger (född 1936) doktorerade vid University of California, Berkeley 1961 och blev sedan tillförordnad professor vid University of Pennsylvania 1962. Han hade sedan en professur där mellan 1967 och 1982. Från och med 1982 har han en professur i fysik vid University of California, Santa Barbara och leder “Institute for Polymers and Organic Solids”. 1990 startade han företaget UNIAX Corporation där han är styrelseordförande.

Prof. Alan J. Heeger

Institute for Polymers and Organic Solids

And Department of Physics and Materials

University of California at Santa Barbara

Santa Barbara, CA 93106-5090

Alan G. MacDiarmid (född 1927) är uppvuxen i Nya Zealand, men doktorerade vid University of Wisconsin 1953 och vid University of Cambridge, England, 1955. Han blev tillförordnad professor vid University of Pennsylvania 1956 och fick en professur där 1964. Sedan 1988 innehar han Blanchard professuren i kemi.

Prof. Alan G. MacDiarmid

University of Pennsylvania

34th and Spruce Streets

Philadelphia, PA 19104

Hideki Shirakawa (född 1936) doktorerade vid Tokyo Institute of Technology 1966 och blev tillförordnad professor vid “Institute of Materials Science” vid University of Tsukuba 1966. Han är professor där sedan 1982.

Prof. Hideki Shirakawa

Institute of Materials Sciences

University of Tsukuba

Sakura-mura, Ibaraki 305, Japan

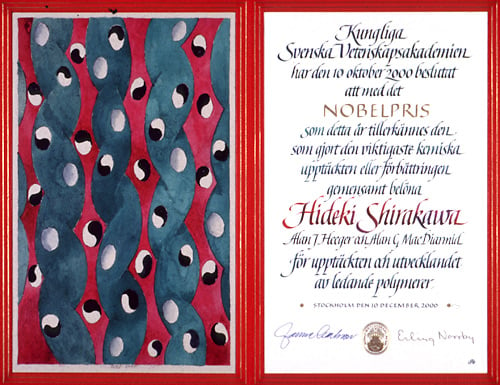

Hideki Shirakawa – Nobel diploma

Copyright © The Nobel Foundation 2000

Artist: Nils G Stenqvist

Calligrapher: Annika Rücker

Hideki Shirakawa – Nobel Lecture

Hideki Shirakawa held his Nobel Lecture December 8, 2000, at Aula Magna, Stockholm University. He was presented by Professor Bengt Nordén, Chairman of the Nobel Committee for Chemistry.

Read the Nobel Lecture

Pdf 4.13 MB

Hideki Shirakawa – Interview

Interview with the 2000 Nobel Laureates in Chemistry Alan Heeger, Alan G. MacDiarmid and Hideki Shirakawa by Joanna Rose, science writer, 12 December 2000.

The Laureates talk about their scientific work together during the years; the importance of interdisciplinary collaboration (7:37); research problems (11:06); the process of discovery (17:37); characteristics of a good scientist (19:58); and their respective recreational interests (22:31).

Interview transcript

Alan Heeger, Alan MacDiarmid and Hideki Shirakawa, I’d like to welcome you to the Nobel E-museum and also to congratulate you to the Nobel Prize in Chemistry.

Alan Heeger, Alan MacDiarmid, Hideki Shirakawa: Thank you.

For the discovery and development of electrically conductive polymers, plastics. You’re some of the extraordinary trio in the Nobel Prize context, I would say, as you have been collaborating together for a very long time. How did you do? Alan.

Alan Heeger: How did we begin the collaboration?

Yes.

Alan Heeger: Early on in the middle 1970s, there was a great deal of interest in the physics community in the metal insulator transition and the nature of metals and what was required to make a system metallic to allow the electrons in a solid to become free. I was very interested in that, and I contacted Alan MacDiarmid as a colleague who had experience in a certain class of materials where it seemed that one might be able to approach some of these fundamental questions. We had a lot of difficulty in the beginning just communicating. We both speak, well, English, I mean he speaks English with a New Zealand accent and sometimes that caused trouble too but …

Alan MacDiarmid: That was your American accent that was the trouble.

Alan Heeger: … but it was the scientific language issues, not just the language, I mean seriously, the concepts from chemistry and the concepts for physics in many cases even overlap but the way you express them is sufficiently different that it was difficult for us to understand one another. We began a collaboration and came to that point in a collaboration where we were trusting of one another and confident with one another, which is of course the essential point of a true collaboration. When Alan had the opportunity to go to Japan and met Hideki Shirakawa and I’ll let you tell that story, but then after that the three of us worked together in Philadelphia.

So that was 1976, when we began. Alan MacDiarmid and I began working together I think in 1975, so that’s a quarter of a century and a lot has happened, but it’s been an exciting time for all three of us to see those initial attempts and initial discoveries develop into what is today a major scientific field.

So how did you, Hideki Shirakawa, jump into this collaboration?

Hideki Shirakawa: For me it was a very lucky chance, but before then I had never been to United States for a starter, so when Professor MacDiarmid asked me if I would have a chance to come to the United States, I was delighted to receive your offer.

Alan MacDiarmid: I guess we first met over a cup of green tea at Tokyo Institute of Technology, right?

Hideki Shirakawa: Right. Yes.

And it was just accidental? Just chance, or?

Hideki Shirakawa: Maybe it was accidental because I know that Alan gave a lecture on silicone chemistry. Usually, the seminar was announced by a very large poster and the poster says that Alan MacDiarmid give the seminar on organic silicone chemistry and then the very small letter subtitle and the addition of, maybe, that (SN)x so I saw the large letter but we missed to read the (SN)x. Before then I know that (SN)x is interesting material, one dimensional conductor and I learned about it but I missed it and I …

Alan Heeger: You missed the talk.

Alan MacDiarmid: You never went to my lecture, I’ve never forgiven you.

Hideki Shirakawa: After the lecture, what shall I say? The organiser of the seminar, Professor Yamomoto told me come to here to show the metallic other polyacetylene film so I brought my samples and I showed him.

Alan MacDiarmid: But you were sitting exactly on my left hand side, as you are now.

Hideki Shirakawa: Oh, you know. Your memory is good.

Alan MacDiarmid: Very important time.

And you immediately saw that this is interesting for you? This is what …

Alan Heeger: The visual impression is strong but more than that, both of these men as scientists are very visual and they’re very sensitive to what they see. Perhaps that’s more typical of chemists than of other scientists, but the colour, the lustrous aspects wouldn’t have caught my imagination the way it caught their imagination and they each saw this golden colour of the polysulphate nitride and the shiny lustrous colour of the polyacetylene and it was a point that brought together, maybe we should try something here.

Alan MacDiarmid: This is what quite often that we have said as chemists, the thing that’s attractive as to the field at the beginning was the unusual silvery colour of a polymer of a plastic, so I think we tend to think in the form of pictures and we picture electrons as little red dots running around and Alan, as I’ve often said, tends to think in terms of mathematical equations which I can never understand, so this is one of the fun things in interacting.

Alan Heeger: That’s why you need a scientific collaboration. In fact, this development, this discovery and subsequent development as the citation of the prize, is right on the boundary of really three disciplines – physics and chemistry and material science – and it just could not have been developed without input from these various different disciplines.

Yes. And there is actually the phrase in the motivation for the prize, “for the consequences of cross disciplinary development between physics and chemistry”. This is in the official paper.

Alan Heeger: If there is a long-term consequence of this work, I think that will be one, the legitimacy and the encouragement of inter-disciplinary science. I also think we’re going to see significant commercial products and applications from these materials but from the point of view of the science, perhaps we pointed the way in inter-disciplinary research and making that a desirable and wonderful thing to do rather than something to be discouraged.

Alan MacDiarmid: Or saying the same thing in different words, that possibly this particular award is a truly excellent example world wide of the importance and what can be done in inter-disciplinary collaboration and I think we all believe that this inter-disciplinary collaboration is going to become more and more important in the future years where ideally I think one will not know in a given research group whether a person’s a chemist or a physicist or an electronic engineer or a biologist. One is a scientist.

Alan Heeger: I somewhat disagree. I think we need to have, as scientists, a core where we are really confident and really expert. I think that in this case, for example, we took on, with hindsight, we took on a very complex problem and if we didn’t have the solid foundation of the work that you did, Hideki, of structure and the microscopy and the cis and the trans and the molecular structure and even the crystal structure, I mean, we knew these things. If we hadn’t had that, we could not have moved forward. The scientific community would have just driven us back, you know, without that foundation, so it was really important that we each of us had some really solid core. Now then we, I think, Alan, I agree with you, we then each of us expanded into and beyond where our core was. I think that we need to educate people as physicists and chemists and we need to encourage them to take on inter-disciplinary work but not too soon in their career.

Alan MacDiarmid: This is exactly what I meant, that we were all trained in different disciplines but then the next step is to encourage the interaction of persons who have been trained in different disciplines to tackle the same problem simultaneously.

Hideki Shirakawa: Before we began the collaboration, each of us had enough accumulation of knowledge on each field. That is important.

Alan Heeger: Of course.

Hideki Shirakawa: That was important, yes.

So, this is where you started to collaborate, that you could pass through the obstacles of being cross disciplinary?

Hideki Shirakawa: Right.

What were the obstacles?

Alan Heeger: The obstacles are very, very real. Part of the obstacles are of course these language issues and the different concepts, but I think in this case it was more than that. I mean, we were taking on a really difficult problem with hindsight. We were either courageous or foolish because it was a very difficult problem and if you look back at it at that time and say how would you get through this? Even in the 1990s, which is now, let’s say, 20 years after the original discoveries, there were many people in the scientific community, our colleagues, who seriously doubted that you could ever achieve the purity in the materials that you would need to make, for example, semiconductor devices. Turns out that you can, turns out that you can do so for very fundamental reasons but we didn’t know that early on and so you just go ahead, it’ll work out.

So how did you manage? How did you manage to get funding, for example?

Alan MacDiarmid: The funding aspect is, as we have been discussing recently during this Nobel week, I think, very important indeed and, Hideki and Alan, just last week I was looking at our original letter when we submitted our first communication, and we sent a copy of this letter to Dr Ken Wynn at the Office of Naval Research. Here we apologised for the fact that most of the work – we actually had this in the second to last paragraph in the letter written 23 years ago – we apologised for the fact that most of the work had been done on moonlighting, moonlighting on other grants. But we then said that the other grants were acknowledged and of course by moonlighting, one refers to the fact where one is actually doing research which is not necessarily encompassed in a given subject matter for which we are receiving funding.

Alan Heeger: But the agencies which supplied those funds were very pleased. I mean, success is success. The early work that we did together was indeed spectacular, although, I must say, the first papers were not easily accepted by the appropriate journals, but once it got out, I mean, it was clearly an exciting time and funding was not a problem. I think, as I recall, the biggest issue in that context, in a slightly larger context, was that there was immediately a positive response by industry. They saw the potential, the dream of a new class of materials which would have the electrical and optical properties of metals but retain the processing advantages and mechanical properties of plastics, but it wasn’t true then. It was still a dream. It was 20 years away or whatever and so there was this initial big push, I would say, or at least start-up of quite a lot of activity in industrial laboratories and they quickly became disillusioned. It was only because the funding agencies that were supporting the universities and supported our programmes and our colleagues around the world that we got through this valley, because it did take, let’s say, 15 years before we began to see materials that might someday be really useful.

Alan MacDiarmid: I think in this respect, to stress again the difficulty we had in convincing some of our colleagues that one could work in an area of dirty nasty organic polymers, not nice crystal and materials. There’s one person, a colleague we were discussing within the very early days, concerning collaborative interaction and I remember well this person said something which represented the opinion of many. He said Alan, you know, all of this is a junk effect, don’t touch it. Then I said to this person, well, if you know what the junk is and you know how to put it in controllably and you know how to take it out controllably, could you not possibly call it a doping effect? But I think this overall fell in the past, in the whole area of electronic materials. The physicists, both academic and those in industry, had been dealing with nice, clean crystal inorganic materials and now you came to a yucky polymer, not nicely crystal and just urgh, you wouldn’t touch it.

Hideki Shirakawa: Speaking about the founding, Japan has a really different system as far as the university concerns. The faculty in the National University has received maybe one or two million yen per year without any proposer so within that money we can do without any restriction. I mean, that as I …

Alan Heeger: As you want.

Hideki Shirakawa: As I want to.

Alan MacDiarmid: That’s good.

Hideki Shirakawa: In that sense, the basic research can do.

Alan MacDiarmid: That is still the case, Hideki?

Hideki Shirakawa: Yes, it’s still, yes.

Alan MacDiarmid: That’s excellent.

That’s what I wonder, how do you actually do a discovery? Is it a trial and error process? How do you come into the discovery?

Alan Heeger: No, no, discovery is discovery. You don’t predict it, right, and it comes in its time. You can be aware of events in a field so that perhaps you’re prepared. You can be aware that something’s going on over here that will stimulate your mind, but discovery is discovery. What can one say?

Hideki Shirakawa: And it’s very difficult to predict.

Alan MacDiarmid: Or if you put it in other terms, that if you plot, say, a straight line, here you have known data and then from the known data, then in principle you can extrapolate to the future new types of phenomena based on that known data but it’s an extrapolation of the curve; but the real exciting things are where, rather than extrapolation of the curve, you have a point way over here which is not on the curve, which is not data which you do not necessarily expect from the data and information which is already known. But once you get that new point and look at it for a while, then you can look back and say yes, of course, this is exactly what you’d expect. But at the time you get it, you don’t.

Alan Heeger: And the other aspect, I suppose, of discovery is to come to a conclusion on the basis of too few facts to really get you that conclusion that enables you then to say, well let’s try that, ok? And then you have a discovery, ok? In that sense, you can’t deduce the result from the facts that you have but by being creative, you can say well, put these ideas together in your mind and it makes something whole to you. Of course, it’s still a hypothesis and then it works and then you’re off and running?

Alan MacDiarmid: Or it doesn’t work and then you modify the hypothesis accordingly.

What is the characteristics of a good scientist? Is it high IQ or being creative, as you say?

Hideki Shirakawa: Their personality should be very curious, ask why, ask what happens and have many interests in everything.

Alan MacDiarmid: Or in other words, I feel one has to live it, eat it, dream it, sleep it, has to be complete immersion and I like to try to point out to some of my students at times that the creative scientist is just as much an artist as a person composing a symphony or painting a beautiful painting and I say have you ever heard of a composer who has started composing his symphony at 9 o’clock in the morning and composes it to 12 noon and then goes out and has lunch with his friends and plays cards and then starts composing his symphony again at 1 o’clock in the afternoon and continues through ‘til 5 o’clock in the afternoon and then goes back home and watches television and opens a can of beer and then starts the next morning composing his symphony? Of course the answer is no. The same thing with a research scientist. You can’t get it out of your mind. It envelopes your whole personality. You have to keep pushing it until you come to the end of a certain segment.

Alan Heeger: Persistence is important. Of course, intelligence and IQ are important, of course, but I was going to say unfortunately or, whatever, I know many people who have far higher IQs that I envy so persistence is very important and also an ability to just focus. The autobiographies that you read about, for example, Einstein as the classic scientist suggest that he could just focus on a problem and just not let go of it for a time and with an intensity that is just far more than most of us can do and evidently that has something to do with success in science.

I know that you both, two Alans, are known for being workaholic, I would say. Do you have any other passions besides science?

Alan MacDiarmid: I like to work hard and play hard. Not very much in between, it’s either work or play and whatever I do, I like to put my full energy into it.

And Alan?

Alan Heeger: Many things. I love the theatre. We have a wonderful theatre group in Santa Barbara and I’m on the board of directors of that theatre group and support it and Ruth and I always like to go to London and to New York to the theatre. I love music. We’re great opera fans. We were at the opera the night before we left to come to Stockholm, but the real passion, I must say, is downhill skiing so I’ve gotten my whole family to be similarly enthusiastic about skiing and in fact we’re all going next week for a holiday to relax from this very hard-working Nobel week for a week of downhill skiing, so as a sport that’s the one that I like.

Alan MacDiarmid: You see, Alan’s skiing is snow skiing. Ours is water-skiing. We have a house beside the largest lake in Pennsylvania in the Pocono mountains and all of my children and my wife and grandchildren, we like to get up very early in the morning, about 6 o’clock when the lake is absolutely flat, before other people have gone out onto the lake, and then we go water-skiing together and we do slalom skiing, also one ski skiing and it’s really fun, I find. This last summer, for example, to be actually out water-skiing not only with my children but with my grandchildren.

Alan Heeger: Oh yes, that’s great fun. How about you Hideki, are you a sportsman?

Hideki Shirakawa: In my case my way to relax is to grow plants and also I keep my garden.

Alan MacDiarmid: I’ve seen your lovely cactus in your garden when I visited.

Alan Heeger: I remember you took cactus plants with you from Philadelphia 25 years ago. Do they still exist?

Hideki Shirakawa: Still exist, yes. Not to large but maybe this size.

Alan Heeger: In Santa Barbara, I planted cactus in one year. The next year, the next year, they really grow.

Do you have any cactuses with you from the Nobel week in Stockholm?

Hideki Shirakawa: Oh no, no.

No time.

Hideki Shirakawa: No time, yes.

Alan MacDiarmid: No Swedish cactus plants, right?

Not this time. Thank you very much Alan MacDiarmid, Alan Heeger and Hideki Shirakawa.

Alan Heeger: Thank you.

Hideki Shirakawa: Thank you.

Alan MacDiarmid: Thank you very much.

Did you find any typos in this text? We would appreciate your assistance in identifying any errors and to let us know. Thank you for taking the time to report the errors by sending us an e-mail.

Alan G. MacDiarmid – Photo gallery

Alan G. MacDiarmid receiving his Nobel

Prize from His Majesty the King at the Stockholm Concert Hall 2000.

Copyright © The Nobel Foundation 2000

Alan G. MacDiarmid after receiving his Nobel

Prize from His Majesty the King at the Stockholm Concert Hall 2000.

Copyright © The Nobel Foundation 2000

The Nobel Laureates assembled at the Stockholm Concert Hall

(front row). Arvid Carlsson is sixth from right.

Copyright © The Nobel Foundation 2000

Photo: Hans Mehlin

Photo: Hans Mehlin

Photo: Hans Mehlin

Hideki Shirakawa – Photo gallery

Hideki Shirakawa receiving his Nobel

Prize from His Majesty the King at the Stockholm Concert Hall 2000.

Copyright © The Nobel Foundation 2000

Hideki Shirakawa after receiving his Nobel

Prize from His Majesty the King at the Stockholm Concert Hall 2000.

Copyright © The Nobel Foundation 2000

The Nobel Laureates assembled at the Stockholm Concert Hall

(front row). Arvid Carlsson is sixth from right.

Copyright © The Nobel Foundation 2000

Photo: Hans Mehlin

Photo: Hans Mehlin

Photo: Hans Mehlin

Alan G. MacDiarmid – Prize presentation

Watch a video clip of the 2000 Nobel Laureate in Chemistry, Alan G. MacDiarmid, receiving his Nobel Prize medal and diploma during the Nobel Prize Award Ceremony at the Concert Hall in Stockholm, Sweden, on 10 December 2000.

Hideki Shirakawa – Prize presentation

Watch a video clip of the 2000 Nobel Laureate in Chemistry, Hideki Shirakawa, receiving his Nobel Prize medal and diploma during the Nobel Prize Award Ceremony at the Concert Hall in Stockholm, Sweden, on 10 December 2000.

Alan Heeger – Nobel Lecture

Alan Heeger held his Nobel Lecture December 8, 2000, at Aula Magna, Stockholm University. He was presented by Professor Bengt Nordén, Chairman of the Nobel Committee for Chemistry.

Alan Heeger held his Nobel Lecture December 8, 2000, at Aula Magna, Stockholm University. He was presented by Professor Bengt Nordén, Chairman of the Nobel Committee for Chemistry.

Read the Nobel Lecture

Pdf 2.23 MB