Juan Ramón Jiménez – Other resources

Links to other sites

On Juan Ramón Jiménez from Pegasos Author’s Calendar

On Juan Ramón Jiménez from The Poetry Foundation

Juan Ramón Jiménez – Banquet speech

As the Laureate was unable to be present at the Nobel Banquet at the Swedish Academy in Stockholm, December 10, 1956, the speech was read by Jaime Benitez, Rector of the University of Puerto Rico

Juan Ramón Jiménez has given me the following message to convey to you:

«I accept with gratitude the undeserved honour which this illustrious Swedish Academy has seen fit to bestow upon me. Besieged by sorrow and sickness, I must remain in Puerto Rico, unable to participate directly in the solemnities. And so that you may have the living testimony of my own intimate feelings gathered in day-by-day association of friendship firmly established in this land of Puerto Rico, I have asked Rector Jaime Benitez of its University, where I am a member of the faculty, to be my personal representative before you in all ceremonies connected with the Nobel Prize awards of 1956.»

I have found such affection for Juan Ramón Jiménez and such understanding for his works that I trust you will excuse me if I single out for special thanks one among you so wise and penetrating that I am certain all others will be glad to be recognized in him. I refer to your own great poet Hjalmar Gullberg, whose presentation this afternoon we shall always remember and whose rendition of Juan Ramón Jiménez’ poetry has brought to the Scandinavian people the clear purity of our Andalusian master.

Juan Ramón Jiménez has asked me also to say this: «My wife Zenobia is the true winner of this Prize. Her companionship, her help, her inspiration made, for forty years, my work possible. Today, without her, I am desolate and helpless.»

I have heard from the trembling lips of Juan Ramón Jiménez some of the most touching expressions of despair. For Juan Ramón is such a poet that his every word reflects his own internal kingdom. We fervently hope that someday his sorrow will be expressed in writing and that the memory of Zenobia will provide renewed and everlasting inspiration to that great master of Hispanic letters, Juan Ramón Jiménez, whom you have honoured so signally today.

Prior to the speech, R. Granit, Member of the Royal Academy of Sciences, made the following remarks about the Spanish poet: «Juan Ramón has been called a poet for poets, but the layman can approach him if willing first to partake passively of the sheer visual beauty of his landscape, lovely Andalusia, its birds, its flowers, pomegranates, and oranges. Once inside his world, by leisurely reading and rereading, one gradually awakens to a new «living insight» into it, refreshed by the depth and richness of a rare poetical imagination. While doing so I recalled a conversation between the painter Degas and the poet Mallarmé, as related by Paul Valéry. Degas, struggling with a sonnet, complained of the difficulties, and finally exclaimed: ‹And yet I do not lack ideas…› Mallarmé with great mildness replied: ‹But Degas, one does not create poetry with ideas. One does it with words.› If ever there has been inspired use of words, it is in Juan Ramón Jiménez’ poetry, and in this sense he is a poet for poets. This is probably also the reason why, within the whole Spanish-speaking world, he is regarded as the teacher and master.

The literary awards may involve decisions more difficult than the scientific ones. Yet we should be grateful to the founder for having included a literary Prize in his will. It adds dignity to the other awards and to the act itself; it emphasizes the human and cultural element which the two worlds of creative imagination have in common; and perhaps, in the end, it expresses deeper insights than scientists can ever achieve.»

Juan Ramón Jiménez – Bibliography

| Selected works in Spanish |

| Almas de violeta. – Madrid : Moderna, 1900 |

| Ninfeas. – Madrid : Moderna, 1900 |

| Rimas. – Madrid : Fernando Fé, 1902 |

| Arias tristes. – Madrid : Fernando Fé, 1903 |

| Jardines lejanos. – Madrid : Fernando Fé, 1904 |

| Elegías puras. – Madrid : Revista de Archivos, 1908 |

| Elegías intermedias. – Madrid, 1909 |

| Olvidanzas. – Madrid : Revista de Archivos, 1909 |

| Elegías lamentables. – Madrid, 1910 |

| Baladas de primavera. – Madrid : Revista de Archivos, 1910 |

| Poemas mágicos y dolientes. – Madrid : Revista de Archivos, 1911 |

| La soledad sonora. – Madrid : Revista de Archivos, 1911 |

| Pastorales. – Madrid : Renacimiento, 1911 |

| Poemas mágicos y dolientes. – Madrid : Revista de Archivos, 1911 |

| Melancolía. – Madrid : Revista de Archivos, 1912 |

| Laberinto. – Madrid : Renacimiento, 1913 |

| Platero y yo : elegía andaluza. .– Madrid : La Lectura, 1914 |

| Estío. – Madrid : Calleja, 1916 |

| Sonetos espirituales. – Madrid : Calleja, 1917 |

| Diario de un poeta recién casado. – Madrid : Calleja, 1917 |

| Poesías escojidas. – New York : Hispanic Society of America, 1917 |

| Eternidades. – Madrid : Angel de Alcoy, 1918 |

| Piedra y cielo. – Madrid : Fortanet, 1919 |

| Antolojía poetica. – Buenos Aires : Losada, 1922 |

| Poesías. – Madrid : Talleres Poligráficos, 1923 |

| Poesías en prosa y verso. – Madrid : Signo, 1923 |

| Belleza. – Madrid : Talleres Poligráficos, 1923 |

| La realidad invisible : Libro inédito. – Madrid, 1924 |

| Sucesión. – Madrid : Signo, 1932 |

| Canción. – Madrid : Signo, 1936 |

| Política poética. – Madrid, 1936 |

| Ciego ante ciegos. – Havana, 1938 |

| Españoles de tres mundos. – Buenos Aires : Losada, 1942 |

| Voces de mi copla. – México : Stylo, 1945 |

| El zaratán. – México : Antigua Librería Robredo, 1946 |

| La estación total con las Canciones de la nueva luz. – Buenos Aires : Losada, 1946 |

| Romances de Coral Gables. – México : Stylo, 1948 |

| Animal de fondo. – Buenos Aires : Pleamar, 1949 |

| Moguer. – Madrid, 1958 |

| El romance, rio de la lengua española. – San Juan : University of Puerto Rico, 1959 |

| Olvidos de Granada, 1924-1928. – Río Piedras : University of Puerto Rico, 1960 |

| La corriente infinita : crítica y evocación / recopilación, selección y prólogo de Francisco Garfias. – Madrid : Aguilar, 1961 |

| El trabajo gustoso : conferencias / selección y prólogo de Francisco Garfias. – Madrid : Aguilar, 1961 |

| El modernismo : notas de un curso (1953) / ed., prólogo y notas de Ricardo Gullón y Eugenio Fernández Méndez. – México : Aguilar, 1962 |

| La colina de los chopos. – Barcelona : Vergara, 1963 |

| Sevilla. – Seville : Ixbiliah, 1963 |

| Poemas revividos del tiempo de Moguer. – Barcelona : Chapultepec, 1963 |

| Dios deseado y deseante / introducción, notas y explicación de los poemas por Antonio Sánchez Barbudo. – Madrid : Aguilar, 1964 |

| Libros inéditos de poesía. – 2 vol / selección, ordenación y prólogo de Francisco Garfias. – Madrid : Aguilar, 1964-1967 |

| Retratos líricos. – Madrid : R. Díaz-Casariego, 1965 |

| Estética y ética estética : crítica y complemento. – Madrid : Aguilar, 1967 |

| Fuego y sentimiento. – Madrid : Artes Gráficas L. Pérez, 1969 |

| Con el carbón del sol : antología de prosa lírica. – Madrid : EMESA, 1973 |

| En el otro costado. – Madrid : Júcar, 1974 |

| Crítica paralela. – Madrid : Nárcea, 1975 |

| La obra desnuda. – Seville : Aldebarán, 1976 |

| Leyenda, 1896-1956. – Madrid : Cupsa, 1978 |

| Historias y cuentos. – Barcelona : Bruguera, 1979 |

| Autobiografía y artes poéticas. – Madrid : Libros de Fausto, 1981 |

| Translations into English |

| Fifty Spanish Poems / translated by J. B. Trend. – Oxford : Dolphin, 1950 |

| Platero and I : an Andalusian Elegy / translated by William and Mary Roberts. – New York : Duschnes, 1956 |

| Platero and I / translated by Eloïse Roach. – Austin : University of Texas Press, 1957 |

| Selected Writings / translated by H. R. Hays ; edited by Eugenio Florit. – New York : Farrar, Straus & Cudahy, 1957 |

| Three Hundred Poems, 1903-1953 / translated by Eloïse Roach. – Austin : University of Texas Press, 1962 |

| Forty Poems / translated by Robert Bly. – Madison,Wis. : Sixties, 1967 |

| Platero and I: An Andalusian Elegy, 1907-1916 / translated by Antonio T. de Nicolás. – Boulder, Colo. : Shambhala, 1978 |

| Stories of Life and Death / translated by Antonio T. de Nicolás. – New York : Paragon House, 1985 |

| God Desired and Desiring / translated by Antonio T. de Nicolás. – New York : Paragon House, 1987 |

| Light and Shadows : Selected Poems and Prose / edited by Dennis Maloney. – Fredonia, N.Y. : White Pine Press, 1987 |

| Invisible Reality : (1917-1920, 1924) / translated by Antonio T. de Nicolás. – New York : Paragon House, 1987 |

| Sky and Rock. – Van Nuys, Cal. : C’est moi meme, 1989 |

| Diary of a Newlywed Poet / translated by Hugh A. Harter. – Selinsgrove,Pa. : Susquehanna University Press, 2004 |

| Spiritual Sonnets / translated by Carl W. Cobb. – Lewiston,N.Y. : Edwin Mellen Press, 1996 |

| The Complete Perfectionist : a Poetics of Work / edited and translated by Christopher Maurer. – New York : Doubleday, 1997 |

The Swedish Academy, 2007

Juan Ramón Jiménez – Nominations

Award ceremony speech

Presentation Speech by Hjalmar Gullberg, Member of the Swedish Academy

A long life consecrated to poetry and to beauty has been honoured this year with the Nobel Prize in Literature. He is an old gardener, this Juan Ramón, who has dedicated half a century to the creation of a new rose, a white mystical rose, which will bear his name.

Jardines lejanos (Distant Gardens), 1904, is one of his books from the beginning of the century. In the southern parts of Andalusia, far off the route from Jerez to Seville well known to Swedish tourists, the poet was born in 1881. But his poetry is not a strong and intoxicating wine, and his work not a grandiose mosque turned into a cathedral. It makes you think, rather, of one of those gardens circled by high, whitewashed walls which you see marking a landscape. He who stops a moment and goes in with his camera runs the risk of being deceived. There is nothing singular or picturesque here, only the usual things: fruit trees and the air which vibrates on passing through them, the pond that reflects the sun and the moon, a bird singing. No small minaret has been transformed into an ivory tower in this fertile garden planted in the soil of Arab culture. But the visitor who lingers will notice that the passivity within the walls is deceiving, that the isolation is only of the circumstantial and transitory, of what pretends to be present. He will not fail to observe that the rose has a radiance which demands sharper senses and a new sensibility. There is a beauty which is more than the play and delight of the senses; in front of the visitor the silent gardener suddenly appears like a strict director of souls. At the entrance of the Juanramonian garden the tourist ought to observe the same rules as on entering a mosque: wash his hands and rinse his mouth in the fountain for ablutions, take off his shoes, etc.

The year in which Ramón Jiménez began to publish his melodious verses was, in the history of Spain, a year for an examination of conscience. On December 10, 1898, in Paris, was signed the treaty with the United States by which Spain lost Cuba, Puerto Rico, and the Philippines, as well as what remained of its navy and its prestige. By a stroke of the pen the remnants of a whole colonial empire were eliminated. In Madrid a group of writers took up the pen to reconquer, in their fashion, the world within the boundaries of Spain. Some of them ultimately attained their goals. The Machado brothers, Valle-Inclán, and Unamuno were among them. The “modernists”, as they called themselves, had in turn grouped themselves around their leader, the Nicaraguan Rubén Darío, visiting in Spain. It was Darío also who, at the beginning of the century, sponsored the first book of verses of the new poet, Juan Ramón Jiménez, a book which bore the scarcely martial title, Almas de violeta (Souls of Violet), 1900.

He was not an audacious creator who would present himself on stage in full light. His song arrived, timid and intimate, from a penumbral background, and spoke of the moon and of melancholy with echoes of Schumann and Chopin. He wept with Heine and with his countryman, inspired by Heine, Gustavo Adolfo Bécquer, the exquisite poet to whom some short-sighted admirers gave the name, “golden-haired Nordic King”. In the manner of Verlaine he murmured his Arias tristes (Sad Arias), 1903, in a half-voice. When, little by little but with sure step, he had freed himself from the gentle, captivating arms of French symbolism, the characteristic features of music and intimacy would remain forever impressed on him.

Music and painting – we can note that, in Seville, the young student also studied to be a painter. Just as we speak of the blue and rose periods of Picasso, who was born in the same year, as the historians of literature have called attention to the predominance of different colours in the work of Ramón Jiménez. To the first period belong all the poems in yellow and green – the famous green poem of his disciple Garcia Lorca has its origin here. Later, white predominates, and the nakedness of white characterizes the brilliant, decisive epoch which includes what has been called the second poetic style of Juan Ramón. Here we witness the long period of plenitude of a poet of light. Far off are the melancholy mood-pictures, far off also the anecdotal themes. The poems treat only of poetry and love, and of the landscape and the sea which are identified with poetry and love. A formal asceticism carried to perfection, rejecting every exterior embellishment of the verse, will be the road that will lead to the simplicity that is the supreme form of art, the poetry that the poet calls naked.

This “second style of Juan Ramón” reaches its full development in Diario de un poeta recién casado (Diary of a Newly-Wed Poet) in 1917. In this year the newly-wed poet made his first trip to America and his diary is full of an infinite feeling for the sea, full of oceanic poetry. His books Eternidades (Eternities), 1918, and Piedra y cielo (Stone and Sky), 1919 mark new stages toward the longed-for identification of the “I” with the world; poetry and thought have the purpose of finding “the exact name for things”. Gradually the poems become more concise, naked, transparent; they are, in fact, maxims and aphorisms of the mystical poetics of Juan Ramón.

In his constant zeal to surpass previous achievements, Ramón Jiménez has made a clean slate of his earliest production and has radically modified old poems, gathering those meriting his approval into extensive anthologies. After his volumes Belleza (Beauty) and Poesía (Poetry) in 1923, in his zeal to experiment with new forms, he abandoned the publication of his works in book form and often published without title or author’s name, in the form of sheets or leaflets scattered by the wind. In 1936 the civil war interrupted the projected edition of his works in twenty-one volumes. Animal de fondo (Animal of Depth), 1949, the last book from his period of exile, is, if read by itself, a sample of a work in progress. Today, therefore, it is still premature to discuss this phase which, in literary history, will perhaps carry the title “the last style of Juan Ramón”.

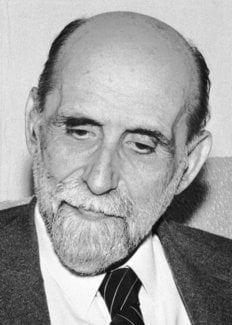

Far away, in what was the colony of Puerto Rico, he is afflicted today by an immense sorrow. It will not be possible for us to see his thin face with its profound eyes and to ask ourselves if it has been taken directly from a painting by El Greco. We find a less solemn self-portrait in the delightful book, Platero y yo (Platero and I), 1914. There, dressed in mourning, the poet passes with his Nazarene beard, riding his little donkey while the gypsy children shout at the top of their voices: The madman! The madman! The madman! … And in truth it is not always easy to distinguish a madman from a poet. But for like spirits the madness of this man has been eminent wisdom. Rafael Alberti, Jorge Guillén, Pedro Salinas, and others who have written their names in the recent history of Spanish poetry have been his disciples; Federico Garcia Lorca is one of them, and so are the Latin American poets, with Gabriela Mistral at their head. I cite the statement of a Swedish journalist on being informed of the Nobel Prize in Literature for this year: “Juan Ramón Jiménez is a born poet, one of those who are born one day with the same simplicity with which the sun’s rays shine, one who purely and simply has been born and has given of himself, unconscious of his natural talents. We do not know when such a poet is born. We know only that one day we find him, we see him, we hear him, just as one day we see a plant flower. We call this a miracle”.

In the annals of the Nobel Prize, Spanish literature has been one of the distant gardens. Very rarely have we cast a glance inside. This year’s laureate is the last survivor of the famous “generation of 1898”. For a generation of poets on both sides of the ocean which separates, and at the same time, unites the Hispanic countries, he has been a master – the master, in effect. When the Swedish Academy renders homage to Juan Ramón Jiménez, it renders homage also to an entire epoch in the glorious Spanish literature.

The Nobel Prize in Literature 1956

Juan Ramón Jiménez – Biographical

Juan Ramón Jiménez (1881-1958) belonged to the group of writers who, in the wake of Spain’s loss of her colonies to the United States (1898), staged a literary revival. The leader of this group of modernistas, as they called themselves, Rubén Darío, helped Juan Ramón to publish Almas de violeta (Souls of Violet), 1900, his first volume of poetry. The years between 1905 to 1912 Ramón Jiménez spent at his birthplace, Moguer, where he wrote Elejías puras (Pure Elegies), 1908, La soledad sonora (Sonorous Solitude), 1911, and Poemas mágicos y dolientes (Magic Poems of Sorrow), 1911. His early poetry was influenced by German Romanticism and French Symbolism. It is strongly visual and dominated by the colours yellow and green. His later style, decisive, formally ascetic, and dominated by white, emerges in the poetic prose of his delicate Platero y yo (Platero and I), 1914, and is fully developed in Diario de un poeta recién casado (Diary of a Newly-Wed Poet), 1917, written during a trip to the United States, as well as in Eternidades (Eternities), 1918, Piedra y cielo (Stone and Sky), 1919, Poesía (Poetry), 1923, and Belleza (Beauty), 1923. In the twenties, Ramón Jiménez became the acknowledged master of the new generation of poets. He was active as a critic as well as an editor of literary journals. In 1930 he retired to Seville to devote himself to the revision of his earlier work. Six years later, as the result of the Spanish Civil War, he left Spain for Puerto Rico and Cuba. He remained in Cuba for three years and, in 1939, went to the United States, which became his residence until 1951, when he moved definitely to Puerto Rico. During these years Juan Ramón taught at various universities and published Españoles de tres mundos (Spaniards of Three Worlds), 1942, a book of prose portraits, and several collections of poems, among them Voces de mi copla (Voices of My Song), 1945, and Animal de fondo (Animal of Depth). The latter book, perhaps his best, clearly reveals the religious preoccupations that filled the last years of the poet’s life. Selections from most of his works were published in English translation in Selected Writings of Juan Ramón Jiménez and Three Hundred Poems, 1903-1953. Ramón Jiménez died in Puerto Rico in 1958.

This autobiography/biography was written at the time of the award and first published in the book series Les Prix Nobel. It was later edited and republished in Nobel Lectures. To cite this document, always state the source as shown above.

Juan Ramón Jiménez died on May 29, 1958.