Vicente Aleixandre – Nobel Lecture

English

December 12, 1977

(Translation)

At a moment like this, so important in the life of a man of letters, I should like to express in the most eloquent words at my command the emotion that a human being feels and the gratitude he experiences in the face of an event such as that which is taking place today. I was born in a middle-class family, but I had the benefit of its eminently open and liberal outlook. My restless spirit led me to practise contradictory professions. I was a teacher of mercantile law, an employee in a railway company, a financial journalist. From early youth this restlessness of which I have spoken lifted me to one particular delight: reading and, in time, writing. At the age of 18 the prentice poet began to write his first verses, sketched out in secret amid the turmoil of a life which, because it had not yet found its true axis, I might call adventurous. The destiny of my life, its direction, was determined by a bodily weakness. I became seriously ill of a chronic complaint. I had to abandon all my other concerns, those which I might call corporal, and to retreat to the countryside far from my former activities. The vacuum thus created was soon invaded by another activity which did not call for physical exertion and could easily be combined with the rest that the doctors had ordered me to take. This unforgettable, all-conquering invasion was the practice of letters; poetry occupied to the full the gap in activity. I began to write with complete dedication and it was then, only then, that I became possessed by the passion which was never to leave me.

Hours of solitude, hours of creation, hours of meditation. Solitude and meditation gave me an awareness, a perspective which I have never lost: that of solidarity with the rest of mankind. Since that time I have always proclaimed that poetry is communication, in the exact sense of that word.

Poetry is a succession of questions which the poet constantly poses. Each poem, each book is a demand, a solicitation, an interrogation, and the answer is tacit, implicit, but also continuous, and the reader gives it to himself through his reading. It is an exquisite dialogue in which the poet questions and the reader silently gives his full answer.

I wish I could find fitting words to describe what a Nobel Prize means to the poet. It cannot be done; I can only assure you that I am with you body and soul, and that the Nobel Prize is as it were the response, not gradual, not tacit, but collected and simultaneous, sudden, of a general voice which generously and miraculously becomes one and itself answers the unceasing question which it has come to address to mankind. Hence my gratitude for this symbol of the collected and simultaneous voice to which the Swedish Academy has enabled me to listen with the senses of the soul for which I here publicly render my devoted thanks.

On the other hand, I consider that a prize such as I have received today is, in all circumstances, and I believe without exception, a prize directed to the literary tradition in which the author concerned – in this case myself – has been formed. For there can be no doubt that poetry, art, are always and above all tradition, and in that tradition each individual author represents at most a modest link in the chain leading to a new kind of aesthetic expression; his fundamental mission is, to use a different metaphor, to pass on a living torch to the younger generation which has to continue the arduous struggle. We can conceive of a poet who has been born with the highest talents to accomplish a destiny. He will be able to do little or nothing unless he has the good fortune to find himself placed in an artistic current of sufficient strength and validity. Conversely, I think that a less gifted poet may perhaps play a more successful role if he is lucky enough to be able to develop himself within a literary movement which is truly creative and alive. In this respect I was born under the protection of benign stars inasmuch as, during a sufficiently long period before my birth, Spanish culture had undergone an extremely important process of swift renewal, a development which I think is no secret to anyone. Novelists such as Galdós; poets like Machado, Unamuno, Juan Ramón Jiménez and, earlier, Becquer; philosophers like Ortega y Gasset; prose writers such as Azorín and Baroja; dramatists such as Valle-Inclán; painters like Picasso and Miró; composers such as de Falla: such figures do not just conjure themselves up, nor are they the products of chance. My generation saw itself aided and enriched by this warm environment, by this source, by this enormously fertile cultural soil, without which perhaps none of us would have become anything.

From the tribune in which I now address you I should like therefore to associate my words with this generous nursery ground of my compatriots who from another era and in the most diverse ways formed us and enabled us, myself and my friends of the same generation, to reach a place from which we could speak with a voice which perhaps was genuine or was peculiar to ourselves.

And I do not refer only to these figures which constitute the immediate tradition, which is always the one most visible and determinative. I allude also to the other tradition, the one of the day before yesterday, which though more distant in time was yet capable of establishing close ties with ourselves; the tradition formed by our classics from the Golden Age, Garcilaso, Fray Luis de León, San Juan de la Cruz, Gongora, Quevedo, Lope de Vega, to which we have also felt linked and from which we have received no little stimulation. Spain was able to revive and renew herself thanks to the fact that, through the generation of Galdós, and later through the generation of 1898, she as it were opened herself, made herself available, and as a result of this the whole of the nourishing sap from the distant past came flowing towards us in overwhelming abundance. The generation of 1927 did not wish to spurn anything of the great deal that remained alive in this splendid world of the past which suddenly lay revealed to our eyes in a lightning flash of uninterrupted beauty. We rejected nothing, except what was mediocre; our generation tended towards affirmation and enthusiasm, not to scepticism or taciturn restraint.

Everything that was of value was of interest to us, no matter whence it came. And if we were revolutionaries, if we were able to be that, it was because we had once loved and absorbed even those values against which we now reacted. We supported ourselves firmly on them in order to brace ourselves for the perilous leap forward to meet our destiny. Thus it should not surprise you that a poet who began as a surrealist today presents a defence of tradition. Tradition and revolution – here are two words which are identical.

And then there was the tradition, not vertical but horizontal, which came to help us in the form of a stimulating and fraternal competition from our flanks, from the side of the road we were pursuing. I refer to that other group of young people (when I too was young) who ran with us in the same race. How fortunate I was to be able to live and perform, to mould myself in the company of poets so admirable as those I came to know and devote myself to with the right of a contemporary! I loved them dearly, every one. I loved them precisely because I was seeking something different, something which it was only possible to find through differences and contrast in relation to these poets, my comrades. Our nature achieves its true individuality only in community with others, face to face with our neighbours. The higher the quality of the human environment in which our personality is formed, the better it is for us. I can say that here, too, I have had the good fortune to be able to realize my destiny through communion with one of the best companies of men of which it is possible to conceive. The time has come to name this company in all its multiplicity: Federico García Lorca, Rafael Alberti, Jorge Guillén, Pedro Salinas, Manuel Altolaguirre, Emilio Prados, Dámaso Alonso, Gerardo Diego, Luis Cernuda.

I speak then of solidarity, of communion, as well as of contrast. If I do so, it is because such has been the feeling that has been most deeply implanted on my soul, and it is its hearbeat that, in one way or another, can be heard most clearly behind the greater part of my verse. It is therefore natural that the very way in which I look upon humanity and poetry has much to do with this feeling. The poet, the truly determinative poet, is always a revealer; he is, essentially, a seer, a prophet. But his “prophecy” is of course not a prophecy about the future; for it may have to do with the past: it is a prophecy without time. Illuminator, aimer of light, chastiser of mankind, the poet is the possessor of a Sesame which in a mysterious way is, so to speak, the word of his destiny.

To sum up, then, the poet is a man who was able to be more than a man: for he is in addition a poet. The poet is full of “wisdom”; but this he cannot pride himself on, for perhaps it is not his own. A power which cannot be explained, a spirit, speaks through his mouth: the spirit of his race, of his peculiar tradition. He stands with his feet firmly planted on the ground, but beneath the soles of his feet a mighty current gathers and is intensified, flowing through his body and finding its way out through his tongue. Then it is the earth itself, the deep earth, that flames from his glowing body. But at other times the poet has grown, and now towards the heights, and with his brow reaching into the heavens, he speaks with a starry voice, with cosmic resonance, while he feels the very wind from the stars fanning his breast. All is then brotherhood and communion. The tiny ant, the soft blade of grass against which his cheek sometimes rests, these are not distinct from himself. And he can understand them and spy out their secret sound, whose delicate note can be heard amidst the rolling of the thunder.

I do not think that the poet is primarily determined by his goldsmith’s work. Perfection in his work is something which he hopes gradually to achieve, and his message will be worth nothing if he offers mankind a coarse and inadequate surface. But emptiness cannot be covered up by the efforts of a polisher, however untiring he may be.

Some poets – this is another problem and one which does not concern expression but the point of departure – are poets of “minorities”. They are artist (how great they are does not matter) who owe their individuality to devoting themselves to exquisite and limited subjects, to refined details (how delicate and profound were the poems that Mallarmé devoted to fans!), to the minutely savoured essences in individuals expressive of our detail-burdened civilization.

Other poets (here, too, their stature is of no importance) turn to what is enduring in man. Not to that which subtly distinguishes but to that which essentially unites. And even though they see man in the midst of the civilization of his own times, they sense all his pure nakedness radiating immutably from beneath his tired vestments. Love, sorrow, hate or death are unchanging. These poets are radical poets and they speak to the primary, the elemental in man. They cannot feel themselves to be the poets of “minorities”. Among them I count myself.

And therefore a poet of my kind has what I would call a communicative vocation. He wants to make himself heard from within each human breast, since his voice is in a way the voice of the collective, the collective to which the poet for a moment lends his passionate voice. Hence the necessity of being understood in languages other than his own. Poetry can only in part be translated. But from this zone of authentic interpretation the poet has the truly extraordinary experience of speaking in another way to other people and being understood by them. And then something unexpected occurs: the reader is installed, as through a miracle, in a culture which in large measure is not his own but in which he can nevertheless feel without difficulty the beating of his own heart, which in this way communicates and lives in two dimensions of reality: its own and that conferred on it by the new home in which it has been received. What has been said remains equally true if we turn it round and apply it not to the reader but to the poet who has been translated into another language. The poet, too, feels himself to be like one of those figures encountered in dreams, which exhibit, perfectly identified, two distinct personalities. Thus it is with the translated author, who feels within himself two personae: the one conferred on him by the new verbal attire which now covers him and his own genuine personae which, beneath the other, still exists and asserts itself.

Thus I conclude by claiming for the poet a role of symbolic representation, enshrining as he does in his own person that longing for solidarity with humankind for which precisely the Nobel Prize was founded.

Vicente Aleixandre – Banquet speech

As the Laureate was unable to be present at the Nobel Banquet, December 10, 1977, the speech of thanks was read by Mr Jorge Padrón (in Spanish)

Majestades, Altezas Reales, Señoras y Señores,

En esta reunión tan grata para todos, unos, la mayoría, están aquí son su presencia física; alguna como yo con su asistencia espiritual. La voz me la presta dignamente Justo Jorge Padrón, a quien doy las gracias muy sinceras. En una reunión como ésta en que nos congregamos, de un modo u otro hombres de procedencias diversas, todos en la convocatoria del Nobel y su llamamiento radicalmente humanista, yo sienta más que nunca lo que en otra parte he expresado: que dicha alta distincion es antes que nada un simbolo de la solidaridad humana. El quiere colaborar en el progreso humano subrayando los pasos que los hombres dan en las más diferentes actividades, todas conducentes al adelantamiento de la comunicación y de la solidaridad en un destino común.

En este alto propósito de Nobel, bajo techo compartido que aquí nos reúne, yo alzo espiritualmente mi copa por el pueblo que lo ha hecho posible por todos los que lo componen. Sea pues mi brindis por este faro de Europa, ejemplo en el esfuerzo por la libertad, justicia y progreso. Levanto pues mi vaso, en la compania de ustedes, por el pueblo sueco y, con él, por quien altamente lo representa en este instante: la Academia Sueca.

Vicente Aleixandre – Documentary

Credit: ITN Archive/Reuters

Vicente Aleixandre – Bibliography

| Works in Spanish |

| Ámbito. – Málaga : Litoral, 1928 |

| Espadas como labios. – Madrid : Espasa–Calpe, 1932 |

| Pasión de la tierra. – Mexico City : Fábula, 1935 |

| La destrucción o el amor. – Madrid : Signo, 1935. – Rev. ed. 1944 |

| Sombra del paraíso. – Madrid : Adán, 1944 |

| En la vida del poeta. – Madrid : Real Academia Española, 1950 |

| Mundo a solas. : 1934-1936. – Madrid : Clan, 1950 |

| Poemas paradisíacos. – Malaga, 1952 |

| Nacimiento último. – Madrid : Insula, 1953 |

| Historia del corazón. – Madrid : Espasa– Calpe, 1954 |

| Algunos caracteres de la nueva poesía española. – Madrid : Instituto de España/Góngora, 1955 |

| Mis poemas mejores. – Madrid : Gredos, 1956 |

| Los encuentros. – Madrid : Guadarrama, 1958 |

| Poesías completas. – Madrid : Aguilar, 1960 |

| Poemas amorosos. – Buenos Aires : Losada, 1960. – Enl. ed. 1970 |

| Antigua casa madrileña. – Santander : Hermanos Bedia, 1961 |

| Picasso. – Málaga : Cuardernos de María Cristina/ Guadalhorce, 1961 |

| En un vasto dominio. – Madrid : Revista de Occidente, 1962 |

| Presencias. – Barcelona : Seix Barral, 1965 |

| Retratos con nombre. – Barcelona : Bardo, 1965 |

| Dos vidas. – Málaga : Guadalhorce, 1967 |

| Poemas de la consumación. – Barcelona : Plaza & Janés, 1968 |

| Obras completas. – Madrid : Aguilar, 1968. – Rev. ed., 2 vol. 1978 |

| Antología del mar y de la noche. – Madrid : Al– Borak, 1971 |

| Poesía superrealista. – Barcelona : Barral, 1971 |

| Sonido de la guerra. – Valencia : Cultura, 1972 |

| Diálogos del conocimiento. – Barcelona : Plaza & Janés, 1974 |

| Antología total. – Barcelona : Seix Barral, 1975 |

| Antología poetíca. – Madrid: Alianza, 1977 |

| Aleixandre para ninos. – Madrid : Ediciones de la Torre, 1984 |

| Los cuadernos de Velintonia : conversaciones con Vicente Aleixandre. – Barcelona : Seix Barral, 1986 |

| Epistolario. – Madrid : Alianza Editorial, 1986 |

| Nuevos poémas varios. – Barcelona : Plaza & Janés, 1987 |

| Prosas recobradas. – Barcelona : Plaza & Janés, 1987 |

| Lo mejor de Vicente Aleixandre : antología total. – Barcelona : Seix Barral, 1989 |

| En gran noche : ultimos poemas. – Barcelona : Seix Barral, 1991 |

| Mire los muros. – Madrid : Ediciones de la Universidad Autonoma de Madrid, 1991 |

| Diálogos del conocimiento. – Madrid : Cátedra, 1992 |

| Mundo a solas. – Madrid : Concejalía de Cultura del Ayuntamiento de Madrid, 1998 |

| Poemas de la consumación. – Madrid : Alianza, 1998 |

| Correspondencia a la generación del 27 (1928–1984). – Madrid : Castalia, 2001 |

| Poesías completas. – Madrid : Visor Libros, 2001 |

| Prosas completas. – Madrid : Visor, 2002 |

| Cartas de Vicente Aleixandre a José Antonio Muñoz Rojas, (1937–1984). – Valencia : Pre–Textos, 2005 |

| Antología de la poesía oral traumática, cósmica y tanática de Vicente Aleixandre. – México : Frente de Afirmación Hispanista, 2005 |

| Translations into English |

| The Cave of Night. – San Luis Obispo, Calif. : Solo Pr., 1976 |

| Destruction or Love / translated by Hugh A. Harter. – Santa Cruz, Cal. : Green Horse Three, 1977 |

| Twenty Poems / translated by Lewis Hyde and Robert Bly. – Madison, Minn. : Seventies Press, 1977 |

| A Longing for the Light :Selected Poems / translated by Lewis Hyde. – New York : Harper & Row, 1979 |

| The Crackling Sun / translated by Louis Bourne. – Madrid : Española de Librería, 1981 |

| A Bird of Paper / translated by Willis Barnstone and David Garrison. – Athens, Ga. : Ohio University Press, 1982 |

| World Alone / translated by Lewis Hyde and David Unger. – Great Barrington, Mass. : Penmaen Press, 1982 |

| Shadow of Paradise / translated by Hugh A. Harter. – Berkeley : University of California Press, 1987 |

| Destruction or Love = La destrucción o el amor / introduction, translation, and illustrations by Robert G. Mowry. – Selinsgrove, Pa. : Susquehanna University Press, 2000 |

| Critical studies (a selection) |

| Bousoño, Carlos, La poesía de Vicente Aleixandre : imágen, estilo, mundo poético. – Madrid, 1950 |

| Schwartz, Kessel, Vicente Aleixandre. – New York : Twayne, 1970 |

| Colinas, Antonio, Conocer, Vicente Aleixandre y su obra. – Barcelona. – Dopesa, 1977 |

| Cano, José Luis, Los cuadernos de Velintonia : conversaciones con Vicente Aleixandre. – Barcelona : Seix Barral, 1986 |

| Murphy, Daniel, Vicente Aleixandre’s Stream of Lyric Consciousness. – Lewisburg, PA : Bucknell Univ. Press, 2001 |

The Swedish Academy, 2006

Vicente Aleixandre – Nobel Lecture

12 Diciembre, 1977

En una hora como esta, tan importante en la vida de un cultivador de las letras, quisiera expresar, con las palabras más bellas, la emoción que un hombre siente y la gratitud que experimenta en unos actos como los que ahora se desarrollan. Yo nací de una familia burguesa, pero tuve la suerte de su vocación, ampliamente abierta y liberal. Mi espíritu inquieto me llevó a ejercer contradictorias profesiones. Fuí profesor de Derecho Mercantil, empleado en una empresa ferroviaria, periodista financiero. Desde joven esta inquietud de que hablo me exaltaba a un placer: la lectura, y, en seguida, la escritura. A los 18 años empezó el aprendiz de poeta a escribir sus primeros versos, que furtivamente yo trazaba, en medio del fragor de una vida, que por no haberse aún centrado en su verdadero eje, yo podría llamar aventurera. El destino de mi vida, el enderezamiento de ésta lo trajo un fallo de mi cuerpo. Caí enfermo de gravedad, de una enfermedad crónica. Hube de abandonar todos mis otros quehaceres que denominaría corporales y escapar al campo, lejos de mis actividades anteriores. El vacío que esto rne dejó lo llenó rápidamente otro quehacer que no necesitaba la colaboración corporal y era compatible con el reposo que los médicos me habían recomendado. Esta invasión inolvidable, desalojadora, fue el ejercicio de las letras; la poesía ocupó plenamente la actividad vacante. Empecé a escribir con dedicación completa, y entonces, realmente, entonces, se adueñó de mí la pasión que no me había de abandonar nunca.

Horas de soledad, horas de creación, horas de meditación. La soledad y la meditación me trajeron un sentimiento nuevo, una perspectiva que no he perdido jamás: la de la solidaridad con los hombres. Desde entonces he proclamado siempre que la poesía es comunicación, empleando la palabra en ese preciso sentido.

La poesía es una sucesión de preguntas que el poeta va haciendo. Cada poema, cada libro es una demanda, una solicitación, una interrogación, y la respuesta es tácita, pero también sucesiva, y se la da el lector con su lectura, a través del tiempo. Hermoso diálogo en que el poeta interroga y el lector calladamente da su plena respuesta.

Con bellas palabras quisiera decir ahora lo que es el Premio Nobel para el poeta. No puede ser; solo me cabe expresar que estoy entre vosotros en cuerpo y alma, y que el Premio Nobel es como la respuesta, no sucesiva, no callada, sino agrupada y coincidente, súbita, de una voz general que generosamente y milagrosamente se hace única y responde a la interrogación sin tregua que ha venido dirigiendo a los hombres. Así, mi gratitud al símbolo de la voz agrupada y simultánea que la Academia Sueca me ha hecho escuchar con los sentidos del alma, y por la cual aquí públicamente le doy mis rendidas gracias.

Por otra parte, estimo que un premio como el que hoy recibo es, en toda circunstancia, y creo que sin excepciones, un premio a la tradición literaria en la que el autor de que se trate, en este caso, mi persona, se ha formado. Pues, sin duda, poesía, arte, es siempre y ante todo, tradición, de la que cada autor no representa otra cosa que la de ser, como máximo, un modesto eslabón de tránsito hacia una expresión estética diferente; alguien cuya fundamental misión es, usando otro símil, transmitir una antorcha viva a la generación más joven, que ha de continuar en la ardua tarea. Puede darse un poeta que haya nacido con las más altas prendas para llevar a término un destino. Nada o muy poco podrá hacer si no tiene la suerte de hallarse situado en una corriente artística de suficiente fuerza o entidad. Creo que, en cambio, acaso un poeta menos dotado haría mejor papel si tuviere la suerte de producirse en medio de un movimiento literario verdaderamente creador y vivo. Yo vine al mundo, en ese sentido, con buena estrella, pues desde un tiempo suficientemente extenso, anterior a mi nacimiento, la cultura española había venido sufriendo un importantísimo proceso de acelerada reviviscencia que hoy, creo, no es un secreto para nadie. Novelistas como Galdós; poetas como Machado, Unamuno, Juan Ramón Jiménez, y, antes, Becquer; filósofos como Ortega y Gasset; prosistas como Azorín y Baroja; hombres de teatro como Valle-Inclán; pintores como Picasso o Miró; músicos como Falla no se improvisan ni son frutos del azar. Mi generación se vio así asistida y enriquecida por ese cálido entorno, por ese manantial, por ese fecundísimo caldo de cultivo, sin el cual acaso nada seríamos ninguno de nosotros.

Desde la tribuna en la que ahora me dirijo a vosotros quiero, pues, asociar mi palabra a la de todo ese plantel generoso de compatriotas míos que desde otra edad y en las más diversas vías nos formaron y nos permitieron, a mi y a mis compañeros de generación, alcanzar un sitio desde el que pudiésemos hablar con una voz tal vez genuina o propia.

Y no me refiero solo a esas figuras que constituyen la tradición inmediata, siempre la más visible y decisiva. Aludo también a la otra tradición, la mediata, si más remota en el tiempo, capaz de enlazar cálidamente con nosotros, la tradición formada por nuestros clásicos del Siglo de Oro, Garcilaso, Fray Luis de León, San Juan de la Cruz, Góngora, Quevedo, Lope de Vega, con la que también nos hemos sentido vinculados, y de la que hemos recibido no pocas esencias. España pudo renacer y renovarse gracias a que, a través de la generación de Galdós y luego a través de la generación del 98, se desobturó, digámoslo así, y se hizo accesible y fluyó abundantemente hacia nosotros toda la savia nutricia que nos llegaba del más remoto pasado. La generación del 27 no quiso desdeñar nada de lo mucho que seguía vivo en ese largo pretérito, abierto de pronto ante nuestra mirada como un largo relámpago de ininterrumpida belleza. No fuimos negadores, sino de la mediocridad; nuestra generación tendía a la afirmación y al entusiasmo, no al escepticismo ni a la taciturna reticencia. Nos interesó vivamente todo cuanto tenía valor, sin importarnos donde éste se hallase. Y si fuimos revolucionarios, si lo pudimos ser, fue porque antes habíamos amado y absorbido incluso aquellos valores contra los que ahora íbamos a reaccionar. Nos apoyábamos fuertemente en ellos para poder así tomar impulso y lanzarnos hacia adelante en brinco temeroso al asalto de nuestro destino. No os asombre, pues, que un poeta que empezó siendo superrealista haga hoy la apología de la tradición. Tradición y revolución. He ahí dos palabras idénticas.

Y luego la tradición, no vertical sino horizontal, la que nos acorría como aliciente y fraternal emulación desde nuestros costados, al lado mismo de nuestro camino. Me refiero a aquel otro grupo de jóvenes (cuando yo lo era también) que corría con nosotros en la misma carrera. Qué suerte la mía poder vivir y tener que hacerme junto a poetas tan admirables como los que yo hube de conocer y asumir en calidad de coetáneos míos! A todos los amé, uno a uno. Y los amé, justamente porque yo buscaba otra cosa; otra cosa que solo era posible hallar por diferenciación y contraste respecto de aquellos poetas, mis compañeros. Nuestro ser solo alcanza, su verdadera individualidad junto a los demás, frente al prójimo. Cuanta mayor calidad tenga ese contorno humano en el que nuestra personalidad se hace, tanto mejor para nosotros. Puedo decir que también aquí yo he tenido la fortuna de haber realizado mi destino desde una de las mejores compañías posibles. Hora es de nombrarla en toda su multiplicidad: Federico García Lorca, Rafael Alberti, Jorge Guillen, Pedro Salinas, Manuel Altolaguirre, Emilio Prados, Dámaso Alonso, Gerardo Diego, Luis Cernuda.

Hablo, pues, de solidaridad, de comunión, y también de contraste. Tal ha sido, por otra parte, el sentimiento que se halla más profundamente inserto en mi alma, y el que late, de un modo u otro, con más fuerza, detrás de la mayoría de mis versos. Es natural entonces que tenga mucho que ver con esto el modo mismo con que entreveo al hombre y a la poesía. El poeta, el decisivo poeta, es siempre un revelador; es, esencialmente, vate, profeta. Pero su “vaticinio” no es, claro está, vaticinio de futuro: porque puede serlo de pretérito: es profecía sin tiempo. Iluminador, asestador de luz, golpeador de los hombres, poseedor de un sésamo que es, en cierto modo, misteriosamente, palabra de su destino.

En definitiva, el poeta es así un hombre que fuese más que un hombre: porque es además poeta. El poeta está lleno de “sabiduría”, pero no puede envanecerse, porque quizá no es suya: una fuerza incognoscible, un espíritu habla por su boca: el de su raza, el de su peculiar tradición. Con los dos pies hincados en la tierra, una corriente prodigiosa se condensa, se agolpa bajo sus plantas para correr por su cuerpo y alzarse por su lengua. Es entonces la tierra misma, la tierra profunda, la que llamea por ese cuerpo arrebatado. Pero otras veces el poeta ha crecido, ahora hacia lo alto, y con su frente incrustada en un cielo habla con voz estelar, con cósmica resonancia, mientras está sintiendo en su pecho el soplo mismo de los astros. Todo se hace fraterno y comunicante. La diminuta hormiga, la brizna de hierba dulce sobre la que su mejilla otras veces descansa, no son distintas de él mismo. Y él puede entenderlas y espiar su secreto sonido, que delicadamente es perceptible entre el rumor del trueno.

No creo que el poeta sea definido primordialmente por su labor de orfebre. La perfección de su obra es gradual aspiración de su factura, y nada valdrá su mensaje si ofrece una tosca o inadecuada superficie a los hombres. Pero la vaciedad no quedará salvada por el tenaz empeño del abrillantador del metal triste.

Unos poetas – otro problema es éste, y no de expresión sino de punto de arranque – son poetas de “minorías”. Son artistas (no importa el tamaño) que se dirigen al hombre atendiendo, cuando se caracterizan, a exquisitos temas estrictos, a refinadas parcialidades (¡ qué delicados y profundos poemas hizo Mallarmé a los abanicos!); a decantadas esencias, del individuo expresivo de nuestra minuciosa civilización.

Otros poetas (tampoco importa el tamaño) se dirigen a lo permanente del hombre. No a lo que refinadamente diferencia, sino a lo que esencialmente une. Y si le ven en medio de su coetánea civilización, sienten su puro desnudo irradiar inmutable bajo sus vestidos cansados. El amor, la tristeza, el odio o la muerte son invariables. Estos poetas son poetas radicales y hablan a lo primario, a lo elemental humano. No pueden sentirse poetas de “minorías”. Entre ellos me cuento.

Por eso, el poeta que yo soy tiene, como digo vocación comunicativa. Quisiera hacerse oir desde cada pecho humano, puesto que, de alguna manera, su voz es la voz de la colectividad, a la que el poeta presta, por un instante, su boca arrebatada. De ahí la necesidad de ser entendido en otras lenguas, distintas a la suya de origen. La poesía sólo en parte puede ser traducida. Pero desde esa zona de auténtico traslado, el poeta hace la experiencia, realmente extraordinaria, de hablar de otro modo a otros hombres y de ser comprendido por ellos. Y entonces ocurre un hecho inesperado. El lector se instala, como por milagro, en una cultura que en buena parte no es la suya, pero desde la que siente palpitar con naturalidad su propio corazón, que de este modo se comunica y vive en dos dimensiones de la realidad: la suya propia y la que le concede el nuevo asilo que le acoge. Lo cual sigue siendo cierto, me parece, vuelto del revés, y referido, no al lector, sino al poeta vertido a otro idioma. También el poeta se siente como esos personajes de los sueños que tienen, perfectamente identificadas, dos personalidades distintas: Así el autor traducido que siente en sí dos personas: la que le confiere la nueva vestidura verbal que ahora le cubre y la suya genuina, que, por debajo de la otra, aún insiste y es.

Termino así recabando para el poeta una representación simbólica: la de cifrar en su persona el anhelo de solidaridad con los hombres, para cuyo logro fue instituido, precisamente, el Premio Nobel.

Vicente Aleixandre – Other resources

Links to other sites

On Vicente Aleixandre from Pegasos Author’s Calendar

Vicente Aleixandre

The Permanent Secretary

Press release

The Nobel Prize in Literature 1977

When Vicente Aleixandre published his first volume of verse in 1928, Ambito, he was already closely associated personally with the greatly gifted Spanish poets who have given this epoch in Spanish literature the name, “The Second Golden Age”. In its conception of poetry’s essence and mode of expression, the vigorous group had something in common with the surrealism that had appeared in France and spread its manifestations from there. Iberian literary circles, however, preferred to assert their independence and drew a literary borderline along the Pyrenees. They were kindred but not allied, and south of the border, the differences were stressed by giving other names to the corresponding impulses in style – ultraism, creationism. It has also happened that the similarities have been recognized and the Gallic term accepted, but the admission has been worded in a challenging way: Spanish surrealiam has given the French surrealism what it has lacked – a poet. The poet referred to was Vicente Aleixandre.

There was in fact good reason for the literary frontier dispute. It could be claimed that the Spanish current had not only taken a divergent course but also had another origin. When this unusually promising generation of Spanish writers banded together to strike their big blow, it was no coincidence that they did so at a spectacular ceremony they themselves had staged on the three hundredth anniversary of Góngora’s death. They share the extravagantly ornamented imagery and the abrupt allusion technique with the French surrealists, but to an equal degree, with the baroque style, especially in its Spanish variant. Furthermore, the penchant for hairsplitting and clear-cut antitheses on the one hand, and for motifs from everyday life on the other, which characterizes much in Spanish modernism and builds on its tradition from the first golden age, is actually incompatible with “l’écriture automatique”, the basic article of faith in the new doctrine from the Seine. And some of the Spaniards did voice their mistrust in this form of inspiration and communication; one of them was, and is, Aleixandre.

His first collection of poem appeared the year after the Góngora anniversary. This means that he was not one of the standard-bearers for the re-orientation of Spanish poetry; that march was well on the move. But he was already one of the company. He had contributed to their magazines and he was their contemporary. Precocity is hardly Aleixandre’s literary characteristic, whereas constant renewal is. He won his place in the group immediately, and it was his own. It was confirmed as time went on, and his position became more and more prominent, founded on a prolific production with masterpieces such as La destrucción o el amor, 1935 (Destruction or Love), Sombra del paraiso, 1944 (The Shadow of Paradise), Nacimiento último, 1953 (The Last Birth), and En un vasto dominio, 1962 (In a Vast Dominion), as perhaps the most important.

There is no formula that sums up this continuously developing poetry, extensive both in time and choice of subject. But if we seek a recurrent impression, a theme which manifests itself in Aleixandre’s work at different stages and in various ways, we can call it: the strength to survive. It is true also of his physical life, his personal existence. In 1925, three years before his début, he fell ill with severe and never-cured renal tuberculosis; since then he has, in brief, been bedridden or a captive at his desk. The civil war came, and from his bed he listened to the bombs exploding. When it was over and his friends and fellow-writers went into exile, they had to leave the invalid behind. But mentally, too, he survived the Franco regime, never submitting, and thus becoming a rallying-point and key figure in what remained of Spain’s spiritual life.

Exemplary, revered, and a guide, frail but unbroken, Aleixandre showed even in his writings the same strength to survive and, what is more, always to renew himself, to explore other means and motifs. His inspiration has neither weakened nor dried up – on the contrary, he has attained a simplicity of expression and a warm openness both to existence and to the reader, which formerly he was not capable of or did not strive for. In this way, strangely enough, his two most recent collections of poems – Poemas de la consumación (Poems about Perfection) from 1968, and perhaps, above all, Diálogos del conocimiento” (Dialogues of Insight), published as recently as three years ago – form the peak hitherto of Vicente Aleixandre’s half century-long writing career.

Award ceremony speech

Presentation Speech by Dr. Karl Ragnar Gierow, of the Swedish Academy

Translation from the Swedish text

Your Majesties, Your Royal Highnesses, Ladies and Gentlemen,

This year’s Nobel prizewinner in literature, Vicente Aleixandre, is hard to understand and in one way controversial. The latter may be due to the former. For even his devoted admirers offer varying interpretations of his poetry. It is doubtful if anyone has yet been able to sum it up properly, one reason being that fifty years after Aleixandre’s debut his writing still seems to be forging ahead. His two most remarkable collections of poems, the twin crowns of his career to date, appeared in 1968 (Poemas de la consumación) and 1974 (Diálogos del conocimiento).

On one point, however, all are agreed: Aleixandre’s place and importance in the spiritual life of Spain. In the history of literature he is part of the current that broke into Spanish poetry in the 1920s with unequalled breadth and force. One of the names of the vigorous avantgarde was the Pleiades. It is all the more suitable as no one with the naked eye can make out the correct number in the group of stars that we colloquially call The Seven Sisters. There are many more of them, and in the firmament of Spanish poetry these Pleiades are usually numbered at around twenty-five – a brilliant cluster of lyric talent. Among those who came to shine the brightest and the longest is Vicente Aleixandre.

The affinity of the new style with French surrealism is striking. There are those in Spain who prefer to call it apparent. They are sometimes reluctant to stress the points in common, asserting their unconformity all the more strongly. The Spanish declaration of independence is not without ground. The Second Golden Age, which is another name for the breakthrough and epoch of the Pleiades, referred directly and expressly to the first, Spain’s century-long age of greatness, the baroque. When the young guard banded together to strike their big blow they chose as a standard to celebrate the 300th anniversary of Luis de Góngora, the creator of the hair-splitting “estilo culto” who originated and gave his name to the ingeniously and extravagantly ornamented gongorism. Virtuose pastiches on Spanish baroque poetry in frills, and beside them folksong variations of rustic themes, were characteristic elements in the renewal during the 1920s south of the Pyrenees, and they distinguish it undeniably from the manifestos up by the Seine.

When this vital generation of poets, with Lorca at the head, stormed the Spanish Parnassus, Aleixandre too was busy with his pen. He was then writing about the need of rationalization and pension and insurance problems on the Spanish railways, where he was employed. But in 1925 something happened which was to determine the whole of his existence and still does today. He was taken seriously ill with renal tuberculosis. It changed his life in two ways. He had to leave his employment and he could take another position with communications of a different kind: those of poetry. When the Góngora anniversary was celebrated he had not yet published his first volume of verse, but he had printed poems in the Pleiades’ magazines and was already a member of the group. He was perhaps the one least concerned about the connexion with “the golden century” and to that extent also the one who came closest to the new doctrines from Paris. This may be the background to a somewhat defiant declaration by one of his poet friends that Spanish surrealism had given French surrealism what it had always lacked – a great poet: Vicente Aleixandre. But he has never been a mediator in this literary frontier dispute. Against the basic article of faith “l’ecriture automatique” he has reiterated his belief in “la conciencia creadora”, creative consciousness. He went his own way.

In extremely simplified terms it is the way from a cosmic vision to a realistic close-up. One of Aleixandre’s conclusive collections of poems is called La destrucción o el amor (Destruction or Love). The title is thematically pregnant with meaning and certain Aleixandre connoisseurs have taken it to mean an Either-Or, to quote Kierkegaard: without love all that is left to us is destruction. But the word “or” can mean not only two alternative contrasts but also an explanatory addition, and what the title then says is: Destruction, in other words love. It would agree better with the perspective of creation in its entirety that these poems, and those that followed, aim at depicting and that Aleixandre has been striving for ever since his debut with Ambito. “Man is an element in the cosmos and in his being does not differ from it”, as he himself says. Love is destruction, but destruction is a result of or an act of love, of self-effacement, of man’s innate yearning to be received back into the world order from which, as a living being, he has been separated and cast out – “segregado – degradado”. His decease therefore has nothing of despair at a meaningful life meeting with a meaningless death. Only with death does life acquire its meaning and is complete; it is the last birth, Nacimiento último, as one of the later collections of poems is called. Aleixandre does not hesitate to carry his vision to the paradoxical extreme: “Man does not exist.” In other words: so long as he is alive, he is actually unborn.

But out of the conviction that man is an element in a cosmic whole grows of necessity the awareness that our short life on earth is also a part of the same course of events. It is that knowledge which has brought Aleixandre back to “the tellurian world”, as he calls it, given his continued writings a proximity to life, an openness and directness which formerly he was not capable of or did not strive for, and has made his last two books, mentioned in the introduction to this presentation, the peak of his work hitherto. On his way there, but conscious of where he was heading, he wrote in Historia del corazón a poem called Entre dos oscuridades un relámpago, A Lightning Between Two Darknesses. In it is the earth, in it is man, and life must be affirmed so long as we have it. Intentionally or not one of the gifted dreamers of our time here quotes the words of another visionary when the meaning of the play is to be explained:

“We are such stuff as dreams are made on,

and our little life is rounded with a sleep.”

Outwardly too Aleixandre went his own way. When the civil war came he was bedridden and listened to the bombs exploding. Lorca was murdered, other poet friends died in prison, and when the remainder went into exile at the end of the war, a constellation scattered to the four winds, they had to leave the invalid behind. But mentally as well Aleixandre survived the regime. He never submitted to it and went on with his writing, frail but unbroken, thereby becoming the rallying-point and source of power in Spain’s spiritual life that we today have the pleasure of honouring.

The Swedish Academy deeply regrets that owing to his state of health Mr Aleixandre can’t be here today. But as his representative we greet his friend and younger colleague, Mr Justo Jorge Padron, and I ask you, Mr Padron, to convey to Mr Aleixandre our warmest congratulations and to receive the Nobel Prize for Literature, awarded to him, from the hands of His Majesty the King.

The Nobel Prize in Literature 1977

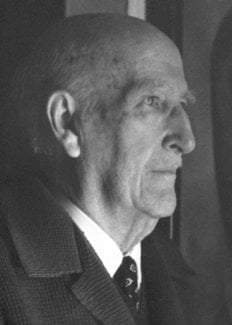

Vicente Aleixandre – Biographical

Vicente Aleixandre was born in Sevilla (Spain) on April 26, 1898. He spent his childhood in Malaga and he has lived in Madrid since 1909. Studied law at the University of Madrid and at the Madrid School of Economics. Beginning in 1925 he has completely devoted himself to literature. His first book of poems, Ambit, appeared in 1928. Since that date he has written and published a score of books. In 1933, he received the National Literary Prize for his work Destruction or Love. He spent the Civil War in the Republican zone. He fell ill and remained in Madrid at the end of the conflict, silenced by the new authorities for four years. In 1944, he published The Shadow of Paradise, still maintaining his independence of the established political situation. In 1950, he became a member of the Spanish Academy. His books and anthologies have been published up to the present day. The Swedish Academy awarded him the Nobel Prize for Literature for the totality of his work in 1977.

Vicente Aleixandre was born in Sevilla (Spain) on April 26, 1898. He spent his childhood in Malaga and he has lived in Madrid since 1909. Studied law at the University of Madrid and at the Madrid School of Economics. Beginning in 1925 he has completely devoted himself to literature. His first book of poems, Ambit, appeared in 1928. Since that date he has written and published a score of books. In 1933, he received the National Literary Prize for his work Destruction or Love. He spent the Civil War in the Republican zone. He fell ill and remained in Madrid at the end of the conflict, silenced by the new authorities for four years. In 1944, he published The Shadow of Paradise, still maintaining his independence of the established political situation. In 1950, he became a member of the Spanish Academy. His books and anthologies have been published up to the present day. The Swedish Academy awarded him the Nobel Prize for Literature for the totality of his work in 1977.

Further works

Sonido de la guerra/Sound of War (poetry), 1978

Epistolario/Letters, 1986

This autobiography/biography was written at the time of the award and first published in the book series Les Prix Nobel. It was later edited and republished in Nobel Lectures. To cite this document, always state the source as shown above.

Vicente Aleixandre died on December 14, 1984.