Isaac Bashevis Singer – Photo gallery

1 (of 1) Isaac Bashevis Singer signing autographs at a reception during Nobel Week in Stockholm, 9 December 1978.

Photo: Chuck Fishman/Getty Images

Isaac Bashevis Singer – Banquet speech

Isaac Bashevis Singer’s speech at the Nobel Banquet, December 10, 1978

Your Majesties, Your Royal Highnesses, Ladies and Gentlemen,

People ask me often, ‘Why do you write in a dying language?’ And I want to explain it in a few words.

Firstly, I like to write ghost stories and nothing fits a ghost better than a dying language. The deader the language the more alive is the ghost. Ghosts love Yiddish and as far as I know, they all speak it.

Secondly, not only do I believe in ghosts, but also in resurrection. I am sure that millions of Yiddish speaking corpses will rise from their graves one day and their first question will be: “Is there any new Yiddish book to read?” For them Yiddish will not be dead.

Thirdly, for 2000 years Hebrew was considered a dead language. Suddenly it became strangely alive. What happened to Hebrew may also happen to Yiddish one day, (although I haven’t the slightest idea how this miracle can take place.)

There is still a fourth minor reason for not forsaking Yiddish and this is: Yiddish may be a dying language but it is the only language I know well. Yiddish is my mother language and a mother is never really dead.

Ladies and Gentlemen: There are five hundred reasons why I began to write for children, but to save time I will mention only ten of them. Number 1) Children read books, not reviews. They don’t give a hoot about the critics. Number 2) Children don’t read to find their identity. Number 3) They don’t read to free themselves of guilt, to quench the thirst for rebellion, or to get rid of alienation. Number 4) They have no use for psychology. Number 5) They detest sociology. Number 6) They don’t try to understand Kafka or Finnegans Wake. Number 7) They still believe in God, the family, angels, devils, witches, goblins, logic, clarity, punctuation, and other such obsolete stuff. Number 8) They love interesting stories, not commentary, guides, or footnotes. Number 9) When a book is boring, they yawn openly, without any shame or fear of authority. Number 10) They don’t expect their beloved writer to redeem humanity. Young as they are, they know that it is not in his power. Only the adults have such childish illusions.

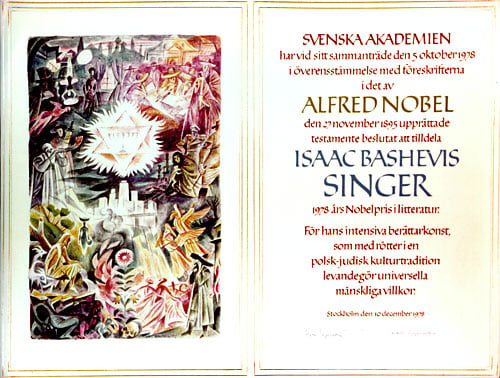

Isaac Bashevis Singer – Nobel diploma

Copyright © The Nobel Foundation 1978

Artist: Gunnar Brusewitz

Calligrapher: Kerstin Anckers

Isaac Bashevis Singer – Bibliography

| Works in Yiddish |

| Der sotn in goray. – Warsaw : Yiddish PEN-Klub, 1935 ; New York : Matones, 1943 |

| Di familye moshkat. – 2 vol. – New York : Sklarsky, 1950 |

| Mayn tatns bes-din shtub. – New York : Der Kval, 1956 ; Tel Aviv : Y. L. Perets, 1979 |

| Gimpel tam un andere dertseylungen. – New York : Tsiko, 1963 |

| Der knekht. – New York : Tsiko, 1967 ; Tel Aviv : Y. L. Perets, 1980 |

| Der kuntsnmakher fun Lublin. – Tel Aviv : Hamenorah, 1971 |

| Mayses fun hintern oyvn – Tel Aviv : Y. L. Perets, 1971 |

| Der bal-tshuve. – Tel Aviv : Y. L. Perets, 1974 |

| Der shpigl un andere dertseylungen. – Jerusalem : Magnes, 1975 |

| Mayn tatns bes-din shtub. – Jerusalem : Magnes, 1996 |

| Works in English |

| The Family Moskat / translated by A. H. Gross. – New York : Knopf, 1950 |

| Satan in Goray / translated by Jacob Sloan. – New York : Noonday, 1955 |

| Gimpel the Fool and Other Stories / translated by Saul Bellow and others. – New York : Noonday, 1957 |

| The Magician of Lublin / translated by Elaine Gottlieb and Joseph Singer. – New York : Noonday, 1960 |

| The Spinoza of Market Street and Other Stories / translated by Martha Glicklich, Cecil Hemley, and others. – New York : Farrar, Straus & Cudahy, 1961 |

| The Slave / translated by Isaac Bashevis Singer and Hemley. – New York : Farrar, Straus & Cudahy, 1962 |

| Short Friday, and Other Stories / translated by Joseph Singer, Roger H. Klein, and others. – New York : Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 1964 |

| In My Father’s Court / translated by Channah Kleinerman-Goldstein, Gottlieb, and Joseph Singer. – New York : Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 1966 |

| Zlateh the Goat and Other Stories / translated by Elizabeth Shub and Isaac Bashevis Singer. – New York : Harper & Row, 1966 |

| Selected Short Stories of Isaac Bashevis Singer / edited by Irving Howe. – New York : Modern Library, 1966 |

| Mazel and Shlimazel; or, The Milk of a Lioness / translated by Shub and Isaac Bashevis Singer. – New York : Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 1967 |

| The Manor / translated by Joseph Singer and Gottlieb. – New York : Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 1967 |

| The Fearsome Inn / translated by Shub and Isaac Bashevis Singer. – New York : Scribners, 1967 |

| When Shlemiel Went to Warsaw and Other Stories / translated by Isaac Bashevis Singer and Shub. – New York : Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 1968; |

| The Séance and Other Stories / translated by Roger H. Klein, Hemley, and others. – New York : Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 1968 |

| A Day of Pleasure : Stories of a Boy Growing Up in Warsaw / translated by Kleinerman-Goldstein and others. – New York : Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 1969 |

| The Estate / translated by Joseph Singer, Gottlieb, and Shub. – New York : Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 1969 |

| Joseph and Koza; or, The Sacrifice to the Vistula / translated by Isaac Bashevis Singer and Shub. – New York : Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 1970 |

| Elijah the Slave : a Hebrew Legend Retold / translated by Isaac Bashevis Singer and Shub. – New York : Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 1970 |

| A Friend of Kafka and Other Stories / translated by Isaac Bashevis Singer, Shub, and others. – New York : Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 1970 |

| An Isaac Bashevis Singer Reader. – New York : Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 1971 |

| Alone in the Wild Forest / translated by Isaac Bashevis Singer and Shub. – New York : Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 1971 |

| The Topsy-Turvy Emperor of China / translated by Isaac Bashevis Singer and Shub. – New York : Harper & Row, 1971 |

| Enemies, a Love Story / translated by Aliza Shevrin and Shub. – New York : Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 1972 |

| The Wicked City / translated by Isaac Bashevis Singer and Shub. – New York : Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 1972 |

| A Crown of Feathers and Other Stories / translated by Isaac Bashevis Singer, Laurie Colwin, and others. – New York : Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 1973 |

| The Hasidim / by Singer and Ira Moskowitz. – New York : Crown, 1973 |

| The Fools of Chelm and Their History / translated by Isaac Bashevis Singer and Shub. – New York : Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 1973 |

| Why Noah Chose the Dove / translated by Shub. – New York : Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 1974 |

| Passions and Other Stories / translated by Isaac Bashevis Singer, Blanche Nevel, Joseph Nevel, and others. – New York : Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 1975 |

| A Tale of Three Wishes. – New York : Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 1975 |

| A Little Boy in Search of God; or, Mysticism in a Personal Light / translated by Joseph Singer. – Garden City, N.Y.: Doubleday, 1976 |

| Naftali the Storyteller and His Horse, Sus, and Other Stories / translated by Joseph Singer, Isaac Bashevis Singer, and others. – New York : Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 1976 |

| Yentl : a Play / by Singer and Leah Napolin. – New York : S. French, 1977 |

| Young Man in Search of Love / translated by Joseph Singer. – Garden City, N.Y.: Doubleday, 1978 |

| Shosha / translated by Joseph Singer and Isaac Bashevis Singer. – New York : Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 1978 |

| Old Love / translated by Joseph Singer, Isaac Bashevis Singer, and others. – New York : Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 1979 |

| Nobel Lecture. – New York : Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 1979 |

| Reaches of Heaven : a Story of the Baal Shem Tov. – New York : Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 1980 |

| The Power of Light : Eight Stories for Hanukkah. – New York : Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 1980 |

| Lost in America / translated by Joseph Singer. – Garden City, N.Y.: Doubleday, 1981 |

| The Collected Stories of Isaac Bashevis Singer. – New York : Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 1982 |

| Isaac Bashevis Singer, Three Complete Novels / translated by Isaac Bashevis Singer and Hemley. – New York : Avenel Books, 1982. – Comprises The Slave; Enemies, A Love Story; and Shosha |

| The Golem. – New York : Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 1982 |

| Yentl the Yeshiva Boy / translated by Marion Magid and Elizabeth Pollet. – New York : Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 1983 |

| The Penitent / translated by Joseph Singer. – New York : Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 1983 |

| Love and Exile : a Memoir. – Garden City, N.Y.: Doubleday, 1984. – Comprises A Little Boy in Search of God; or, Mysticism in a Personal Light; A Young Man in Search of Love; and Lost in America. |

| Stories for Children. – New York : Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 1984 |

| Teibele and Her Demon / by Singer and Eve Friedman. – New York : S. French, 1984 |

| The Image and Other Stories / translated by Isaac Bashevis Singer, Pollet, and others. – New York : Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 1985 |

| Gifts. – Philadelphia : Jewish Publication Society, 1985 |

| The Death of Methuselah and Other Stories / translated by Isaac Bashevis Singer, Lester Goran, and others. – New York : Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 1988 |

| The King of the Fields / translated by Isaac Bashevis Singer. – New York : Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 1988 |

| Scum / translated by Rosaline Dukalsky Schwartz. – New York : Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 1991 |

| My Love Affair with Miami Beach / text by Singer, photographs by Richard Nagler. – New York : Simon & Schuster, 1991 |

| The Certificate / translated by Leonard Wolf. – New York : Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 1992 |

| Meshugah / translated by Isaac Bashevis Singer and Nili Wachtel. – New York : Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 1994 |

| Shrewd Todie and Lyzer the Miser & Other Children’s Stories. – Boston : Barefoot Books, 1994 |

| Shadows on the Hudson / translated by Joseph Sherman. – New York : Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 1998 |

| More Stories from My Father’s Court / translated by Curt Leviant. – New York : Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 2000 |

| Collected stories. – 1. Gimpel the Fool to The Letter Writer. – New York : Library of America, 2004 |

| Collected stories. – 2. A Friend of Kafka to Passions. – New York : Library of America, 2004 |

| Collected stories. – 3. One Night in Brazil to The Death of Methuselah. – New York : Library of America, 2004 |

| Critical studies (a selection) |

| The Achievement of Isaac Bashevis Singer / ed. by Marcia Allentuck. – Carbondale : Southern Ill. U.P., 1969 |

| Critical Views of Isaac Bashevis Singer / ed. by Irving Malin. – New York : New York Univ. Press, 1969 |

| Zamir, Israel, Journey to My Father, Isaac Bashevis Singer. – New York : Arcade, 1995 |

| Hadda, Janet, Isaac Bashevis Singer : a Life. – New York : Oxford University Press, 1997 |

| Telushkin, Dvorah, Master of Dreams : a Memoir of Isaac Bashevis Singer. – New York : Morrow, 1997 |

| Tuszynska, Agata, Lost Landscapes : in Search of Isaac Bashevis Singer and the Jews of Poland. – New York : William Morrow, 1998 |

| Noiville, Florence, Isaac Bashevis Singer. – Paris : Stock, 2003 |

| Isaac Bashevis Singer : an Album / edited by Ilan Stavans ; biographical commentary by James Gibbons. – New York : Library of America, 2004 |

The Swedish Academy, 2006

Isaac Bashevis Singer – Nobel Lecture

8 December 1978

The storyteller and poet of our time, as in any other time, must be an entertainer of the spirit in the full sense of the word, not just a preacher of social or political ideals. There is no paradise for bored readers and no excuse for tedious literature that does not intrigue the reader, uplift him, give him the joy and the escape that true art always grants. Nevertheless, it is also true that the serious writer of our time must be deeply concerned about the problems of his generation. He cannot but see that the power of religion, especially belief in revelation, is weaker today than it was in any other epoch in human history. More and more children grow up without faith in God, without belief in reward and punishment, in the immortality of the soul and even in the validity of ethics. The genuine writer cannot ignore the fact that the family is losing its spiritual foundation. All the dismal prophecies of Oswald Spengler have become realities since the Second World War. No technological achievements can mitigate the disappointment of modern man, his loneliness, his feeling of inferiority, and his fear of war, revolution and terror. Not only has our generation lost faith in Providence but also in man himself, in his institutions and often in those who are nearest to him.

In their despair a number of those who no longer have confidence in the leadership of our society look up to the writer, the master of words. They hope against hope that the man of talent and sensitivity can perhaps rescue civilization. Maybe there is a spark of the prophet in the artist after all.

As the son of a people who received the worst blows that human madness can inflict, I must brood about the forthcoming dangers. I have many times resigned myself to never finding a true way out. But a new hope always emerges telling me that it is not yet too late for all of us to take stock and make a decision. I was brought up to believe in free will. Although I came to doubt all revelation, I can never accept the idea that the Universe is a physical or chemical accident, a result of blind evolution. Even though I learned to recognize the lies, the clichés and the idolatries of the human mind, I still cling to some truths which I think all of us might accept some day. There must be a way for man to attain all possible pleasures, all the powers and knowledge that nature can grant him, and still serve God – a God who speaks in deeds, not in words, and whose vocabulary is the Cosmos.

I am not ashamed to admit that I belong to those who fantasize that literature is capable of bringing new horizons and new perspectives – philosophical, religious, aesthetical and even social. In the history of old Jewish literature there was never any basic difference between the poet and the prophet. Our ancient poetry often became law and a way of life.

Some of my cronies in the cafeteria near the Jewish Daily Forward in New York call me a pessimist and a decadent, but there is always a background of faith behind resignation. I found comfort in such pessimists and decadents as Baudelaire, Verlaine, Edgar Allan Poe, and Strindberg. My interest in psychic research made me find solace in such mystics as your Swedenborg and in our own Rabbi Nachman Bratzlaver, as well as in a great poet of my time, my friend Aaron Zeitlin who died a few years ago and left a literary inheritance of high quality, most of it in Yiddish.

The pessimism of the creative person is not decadence but a mighty passion for the redemption of man. While the poet entertains he continues to search for eternal truths, for the essence of being. In his own fashion he tries to solve the riddle of time and change, to find an answer to suffering, to reveal love in the very abyss of cruelty and injustice. Strange as these words may sound I often play with the idea that when all the social theories collapse and wars and revolutions leave humanity in utter gloom, the poet – whom Plato banned from his Republic – may rise up to save us all.

The high honor bestowed upon me by the Swedish Academy is also a recognition of the Yiddish language – a language of exile, without a land, without frontiers, not supported by any government, a language which possesses no words for weapons, ammunition, military exercises, war tactics; a language that was despised by both gentiles and emancipated Jews. The truth is that what the great religions preached, the Yiddish-speaking people of the ghettos practiced day in and day out. They were the people of The Book in the truest sense of the word. They knew of no greater joy than the study of man and human relations, which they called Torah, Talmud, Mussar, Cabala. The ghetto was not only a place of refuge for a persecuted minority but a great experiment in peace, in self-discipline and in humanism. As such it still exists and refuses to give up in spite of all the brutality that surrounds it. I was brought up among those people. My father’s home on Krochmalna Street in Warsaw was a study house, a court of justice, a house of prayer, of storytelling, as well as a place for weddings and Chassidic banquets. As a child I had heard from my older brother and master, I. J. Singer, who later wrote The Brothers Ashkenazi, all the arguments that the rationalists from Spinoza to Max Nordau brought out against religion. I have heard from my father and mother all the answers that faith in God could offer to those who doubt and search for the truth. In our home and in many other homes the eternal questions were more actual than the latest news in the Yiddish newspaper. In spite of all the disenchantments and all my skepticism I believe that the nations can learn much from those Jews, their way of thinking, their way of bringing up children, their finding happiness where others see nothing but misery and humiliation. To me the Yiddish language and the conduct of those who spoke it are identical. One can find in the Yiddish tongue and in the Yiddish spirit expressions of pious joy, lust for life, longing for the Messiah, patience and deep appreciation of human individuality. There is a quiet humor in Yiddish and a gratitude for every day of life, every crumb of success, each encounter of love. The Yiddish mentality is not haughty. It does not take victory for granted. It does not demand and command but it muddles through, sneaks by, smuggles itself amidst the powers of destruction, knowing somewhere that God’s plan for Creation is still at the very beginning.

There are some who call Yiddish a dead language, but so was Hebrew called for two thousand years. It has been revived in our time in a most remarkable, almost miraculous way. Aramaic was certainly a dead language for centuries but then it brought to light the Zohar, a work of mysticism of sublime value. It is a fact that the classics of Yiddish literature are also the classics of the modern Hebrew literature. Yiddish has not yet said its last word. It contains treasures that have not been revealed to the eyes of the world. It was the tongue of martyrs and saints, of dreamers and Cabalists – rich in humor and in memories that mankind may never forget. In a figurative way, Yiddish is the wise and humble language of us all, the idiom of frightened and hopeful Humanity.

* Disclaimer

Every effort has been made by the publisher to credit organizations and individuals with regard to the supply of audio files. Please notify the publishers regarding corrections.

Isaac Bashevis Singer – Other resources

Links to other sites

On Isaac Bashevis Singer from Pegasos Author’s Calendar

‘American Masters: Isaac Bashevis Singer’ from PBS

Isaac Bashevis Singer Papers at Harry Ransom Center

On Isaac Bashevis Singer from the Library of America

Isaac Bashevis Singer – Facts

Award ceremony speech

Presentation Speech by Professor Lars Gyllensten of the Swedish Academy

Translation from the Swedish text

Your Majesties, Your Royal Highnesses, Ladies and Gentlemen,

“Heaven and earth conspire that everything which has been, be rooted out and reduced to dust. Only the dreamers, who dream while awake, call back the shadows of the past and braid from unspun threads, unspun nets.” These words from one of Isaac Bashevis Singer’s stories in the collection The Spinoza of Market Street (1961) say quite a lot about the writer himself and his narrative art.

Singer was born in a small town or village in eastern Poland and grew up in one of the poor, over-populated Jewish quarters of Warsaw, before and during the First World War. His father was a rabbi of the Hasid school of piety, a spiritual mentor for a motley collection of people who sought his help. Their language was Yiddish – the language of the simple people and of the mothers, with its sources far back in the middle ages and with an influx from several different cultures with which this people had come in contact during the many centuries they had been scattered abroad. It is Singer’s language. And it is a storehouse which has gathered fairytales and anecdotes, wisdom, superstitions and memories for hundreds of years past through a history that seems to have left nothing untried in the way of adventures and afflictions. The Hasid piety was a kind of popular Jewish mysticism. It could merge into prudery and petty-minded, strict adherence to the law. But it could also open out towards orgiastic frenzy and messianic raptures or illusions.

This world was that of East-European Jewry – at once very rich and very poor, peculiar and exotic but also familiar with all human experience behind its strange garb. This world has now been laid waste by the most violent of all the disasters that have overtaken the Jews and other people in Poland. It has been rooted out and reduced to dust. But it comes alive in Singer’s writings, in his waking dreams, his very waking dreams, clear-sighted and free of illusion but also full of broad-mindedness and unsentimental compassion. Fantasy and experience change shape. The evocative power of Singer’s inspiration acquires the stamp of reality, and reality is lifted up by dreams and imagination into the sphere of the supernatural, where nothing is impossible and nothing is sure.

Singer began his writing career in Warsaw in the years between the wars. Contact with the secularized environment and the surging social and cultural currents involved a liberation from the setting in which he had grown up – but also a conflict. The clash between tradition and renewal, between other-worldliness and pious mysticism on the one hand and free thought, doubt and nihilism on the other, is an essential theme in Singer’s short stories and novels. Among many other themes, it is dealt with in Singer’s big family chronicles – the novels The Family Moskat, The Manor and The Estate, from the 1950s and 1960s. These extensive epic works depict how old Jewish families are broken up by the new age and its demands and how they are split, socially and humanly. The author’s apparently inexhaustible psychological fantasy and insight have created a microcosm, or rather a well-populated micro-chaos, out of independent and graphically convincing figures.

Singer’s earliest fictional works, however, were not big novels but short stories and novellas. The novel Satan in Goray appeared in 1935, when the Nazi terror was threatening and just before the author emigrated to the USA, where he has lived and worked ever since. It treats of a theme to which Singer has often returned in different ways – the false Messiah, his seductive arts and successes, the mass hysteria around him, his fall and the breaking up of illusions in destitution and new illusions or in penance and purity. Satan in Goray takes place in the 17th century after the cruel ravages of the Cossacks with outrages and mass murder of Jews and others. The book anticipates what was to come in our time. These people are not wholly evil, not wholly good – they are haunted and harassed by things over which they have no control, by the force of circumstances and by their own passions – something alien but also very close.

This is typical of Singer’s view of humanity – the power and fickle inventiveness of obsession, the destructive but also inflaming and creative potential – of the emotions and their grotesque wealth of variation. The passions can be of the most varied kinds – often sexual but also fanatical hopes and dreams, the figments of terror, the lure of lust or power, the nightmares of anguish. Even boredom can become a restless passion, as with the main character in the tragicomic picaresque novel The Magician of Lublin (1961), a kind of Jewish Don Juan and rogue, who ends up as an ascetic or saint. In a sense a counterpart to this book is The Slave (1962), really a legend of a lifelong, faithful love which becomes a compulsion, forced into fraud despite its purity, heavy to bear though sweet, saintly but with the seeds of shamefulness and deceit. The saint and the rogue are near of kin.

Singer has perhaps given of his best as a consummate storyteller and stylist in the short stories and in the numerous and fantastic novellas, available in English translation in about a dozen collections. The passions and crazes are personified in these strange tales as demons, spectres and ghosts, all kinds of infernal or supernatural powers from the rich storehouse of Jewish popular belief or of his own imagination. These demons are not only graphic literary symbols but also real, tangible forces. The middle ages seem to spring to life again in Singer’s works, the daily round is interwoven with wonders, reality is spun from dreams, the blood of the past pulsates in the present. This is where Singer’s narrative art celebrates its greatest triumphs and bestows a reading experience of a deeply original kind, harrowing but also stimulating and edifying. Many of his characters step with unquestioned authority into the Pantheon of literature where the eternal companions and mythical figures live, tragic – and grotesque, comic and touching, weird and wonderful – people of dream and torment, baseness and grandeur.

Dear Mr. Singer, master and magician! It is my task and my great pleasure to convey to you the heartiest congratulations of the Swedish Academy and to ask you to receive from the hands of His Majesty the King the Nobel Prize for Literature 1978.

The Nobel Prize in Literature 1978

Isaac Bashevis Singer – Biographical

In one of his more light-hearted books, Isaac Bashevis Singer depicts his childhood in one of the over-populated poor quarters of Warsaw, a Jewish quarter, just before and during the First World War. The book, called In My Father’s Court (1966), is sustained by a redeeming, melancholy sense of humour and a clear-sightedness free of illusion. This world has gone forever, destroyed by the most terrible of all scourges that have afflicted the Jews and other people in Poland. But it comes to life in Singer’s memories and writing in general. Its mental and physical environment and its centuries-old traditions have set their stamp on Singer as a man and a writer, and provide the ever-vivid subject matter for his inspiration and imagination. It is the world and life of East European Jewry, such as it was lived in cities and villages, in poverty and persecution, and imbued with sincere piety and rites combined with blind faith and superstition. Its language was Yiddish – the language of the simple people and of the women, the language of the mothers which preserved fairytales and anecdotes, legends and memories for hundreds of years past, through a history which seems to have left nothing untried in the way of agony, passions, aberrations, cruelty and bestiality, but also of heroism, love and self-sacrifice.

Singer’s father was a rabbi, a spiritual mentor and confessor, of the Hasid school of piety. His mother also came from a family of rabbis. The East European Jewish-mystical Hasidism combined Talmud doctrine and a fidelity to scripture and rites – which often merged into prudery and strict adherence to the law – with a lively and sensually candid earthiness that seemed familiar with all human experience. Its world, which the reader encounters in Singer’s stories, is a very Jewish but also a very human world. It appears to include everything – pleasure and suffering, coarseness and subtlety. We find obstrusive carnality, spicy, colourful, fragrant or smelly, lewd or violent. But there is also room for sagacity, worldly wisdom and shrewd speculation. The range extends from the saintly to the demoniacal, from quiet contemplation and sublimity, to ruthless obsession and infernal confusion or destruction. It is typical that among the authors Singer read at an early age who have influenced him and accompanied him through life were Spinoza, Gogol and Dostoievsky, in addition to Talmud, Kabbala and kindred writings.

Singer began his writing career as a journalist in Warsaw in the years between the wars. He was influenced by his elder brother, now dead, who was already an author and who contributed to the younger brother’s spiritual liberation and contact with the new currents of seething political, social and cultural upheaval. The clash between tradition and renewal, between other-worldliness and faith and mysticism on the one hand, and free thought, secularization, doubt and nihilism on the other, is an essential theme in Singer’s short stories and novels. The theme is Jewish, made topical by the barbarous conflicts of our age, a painful drama between contentious loyalties. But it is also of concern to mankind, to us all, Jew or non-Jew, actualized by modern western culture’s struggles between preservation and renewal. Among many other themes, it is dealt with in Singer’s big family chronicles – the novels, The Family Moskat (1950), The Manor (1967), and The Estate (1969). These extensive epic works have been compared with Thomas Mann‘s novel, Buddenbrooks. Like Mann, Singer describes how old families are broken up by the new age and its demands, from the middle of the 19th century up to the Second World War, and how they are split, financially, socially and humanly. But Singer’s chronicles are greater in scope than Mann’s novel and more richly orchestrated in their characterization. The author’s apparently inexhaustible psychological fantasy has created a microcosm, or rather, a well-populated microchaos, out of independent and graphically convincing figures. They bring to mind another writer whom Singer read when young – Leo Tolstoy.

Singer’s earliest fictional works, however, were not big novels but short stories and novellas, a genre in which he has perhaps given his very best as a consummate storyteller and stylist. The novel, Satan in Goray, written originally in Yiddish, like practically all Singer books, appeared in 1935 when the Nazi catastrophe was threatening and just before the author emigrated to the USA, where he has lived and worked ever since. It treats of a theme to which Singer has often returned in different ways and with variations in time, place and personages – the false Messiah, his seductive arts and successes, the mass hysteria around him, his fall and the breaking up of illusions in destitution and new illusion, or in penance and purity. Satan in Goray takes place in the 17th century, in the confusion and the sufferings after the cruel ravages of the Cossacks, with outrages and mass murder of Jews and other wretched peasants and artisans. The people in this novel, as elsewhere with Singer, are often at the mercy of the capricious infliction of circumstance, but even more so, their own passions. The passions are frequently of a sexual nature but also of another kind – manias and superstitions, fanatical hopes and dreams, the figments of terror, the lure of lust or power, the nightmares of anguish, and so on. Even boredom can become a restless passion, as with the main character in the tragi-comic picaresque novel, The Magician of Lublin (1961), a most eccentric anti-hero, a kind of Jewish Don Juan and rogue, who ends up as an ascetic or saint.

This is one of the most characteristic themes with Singer – the tyranny of the passions, the power and fickle inventiveness of obsession, the grotesque wealth of variation, and the destructive, but also inflaming and paradoxically creative potential of the emotions. We encounter this tumultuous and colourful world particularly in Singer’s numerous and fantastic short stories, available in English translation in about a dozen collections, from the early Gimpel The Fool (translated 1953), to the later work, A Crown of Feathers (1973), with notable masterpieces in between, such as, The Spinoza of Market Street (1961), or, A Friend of Kafka (1970). The passions and crazes are personified in Singer as demons, spectres, ghosts and all kinds of infernal or supernatural powers from the rich storehouse of Jewish popular imagination. These demons are not only graphic literary symbols, but also real, tangible beings – Singer, in fact, says he believes in their physical presence. The middle ages rise up in his work and permeate the present. Everyday life is interwoven with wonders, reality spun from dreams, the blood of the past with the moment in which we are living. This is where Singer’s narrative art celebrates its greatest triumphs and bestows a reading experience of a deeply original kind, harrowing, but also stimulating and edifying. Many of his characters step with unquestioned authority into the Pantheon of literature, where the eternal companions and mythical figures live, tragic and grotesque, comic and touching, weird and wonderful people of dream and torment, baseness and grandeur.

| Books |

| Issac Bashevis Singer, born in Leoncin near Warsaw, emigrated 1935 to USA. He died in 1991.

In addition to the works mentioned above Singer’s writings include – in English: |

| the novels |

| The Slave, transl. by the author and Cecil Hemley. New York: Farrar Straus, 1962; London: Secker and Warburg, 1963. |

| Enemies: A Love Story, transl. by Alizah Shevrin and Elizabeth Shub. N.Y.: Farrar Straus, 1972. |

| Shosha. N.Y.: Farrar Straus, 1978. |

| Reaches of Heaven. N.Y.: Farrar Straus, 1980. |

| The Golem. London: Deutsch, 1983. |

| The Penitent. N.Y.: Farrar Straus, 1983. |

| Yentl the Yeshiva Boy, transl. from the Yiddish by Marion Magid and Elisabeth Pallet. N.Y.: Farrar Straus, 1983. |

| The Ring of the Fields. N.Y.: Farrar Straus, 1988. |

| Scum, transl. by Rosaline Dukalsky Schwartz. N.Y.: Farrar Straus, 1991. |

| the collections of short stories |

| Short Friday, transl. by Ruth Whitman and others. N.Y.: Farrar Straus, 1964; London: Seeker and Warburg, 1967. |

| The Seance, transl. by Ruth Whitman and others. N.Y.: Farrar Straus, 1968; London: Cape, 1970. |

| Passions, transl. by the author in collab. with others. N.Y.: Farrar Straus, 1975; London: Cape, 1976. |

| Old Love. N.Y.: Farrar Straus, 1979. |

| The Power of Light. N.Y.: Farrar Straus, 1980. |

| The Image and Other Stories. N.Y.: Farrar Straus, 1985. |

| The Death of Metuselah and Other Stories. London: Cape, 1988. |

| the memoirs |

| A Little Boy in Search of God: Mysticism in a Personal Light. N.Y.: Doubleday, 1976. |

| A Young Man in Search of Love, transl. by Joseph Singer. N.Y.: Doubleday, 1978. |

| Lost in America. N.Y.: Doubleday, 1981. |

| for children |

| Zlateh the Goat and Other Stories, transl. by the author and Elizabeth Shub. N.Y.: Harper, 1966; London: Secker and Warburg, 1967. |

| When Schlemiel Went to Warsaw and Other Stories, transl. by the author and Elizabeth Shub. N.Y.: Farrar Straus, 1968. |

| A Day of Pleasure: Stories of a Boy Growing up in Warsaw, transl. by the author and Elizabeth Shub. N.Y.: Farrar Straus, 1969. |

| The Fools of Chelm and Their History, transl. by the author and Elizabeth Shub. N.Y.: Farrar Straus, 1973. |

| Why Noah Chose the Dove, transl. by Elizabeth Shub. N.Y.: Farrar Straus, 1974. |

| Stories for Children. N.Y.: Farrar Straus, 1986. |

This autobiography/biography was written at the time of the award and first published in the book series Les Prix Nobel. It was later edited and republished in Nobel Lectures. To cite this document, always state the source as shown above.

Isaac Bashevir Singer died on July 24, 1991.