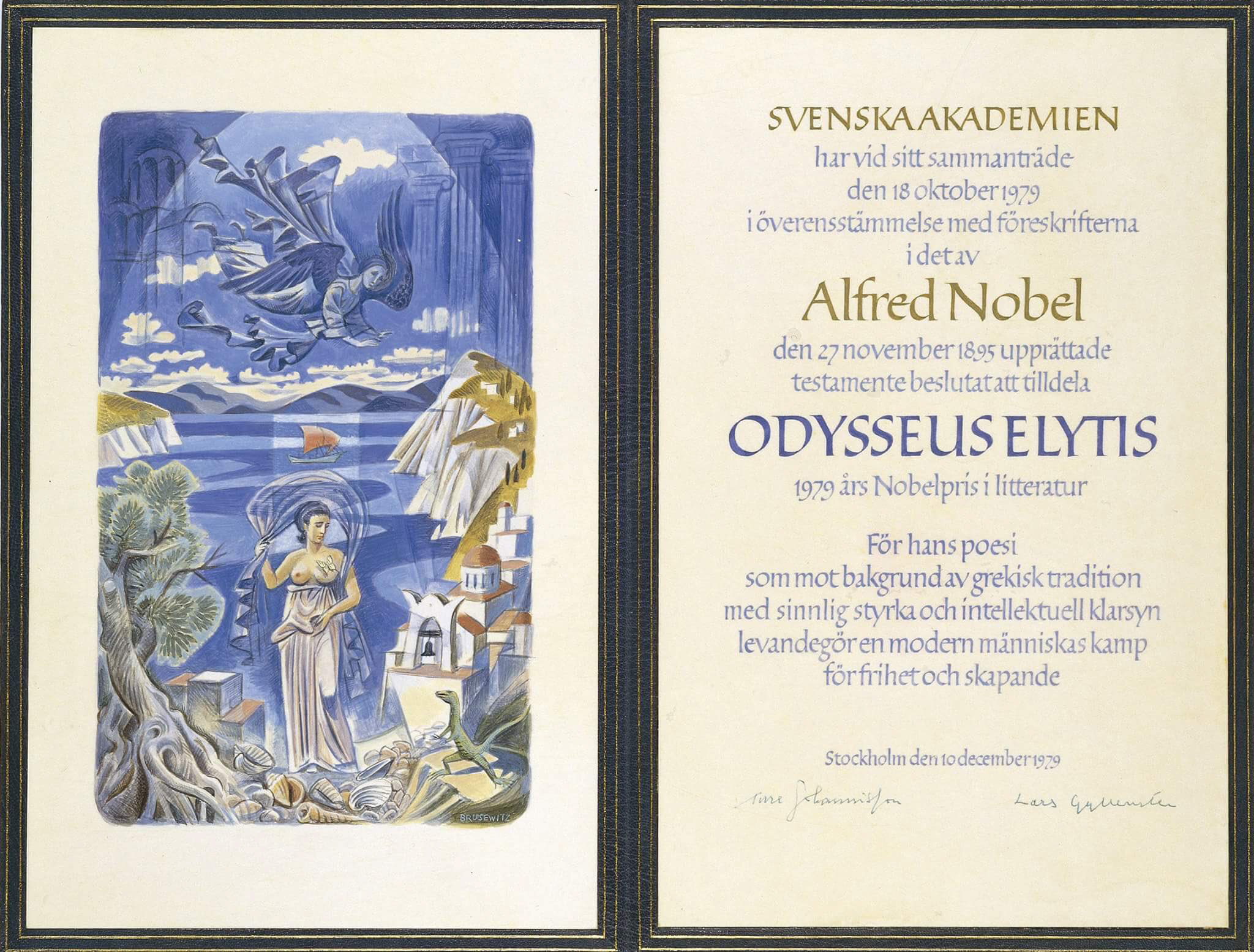

Odysseus Elytis – Nobel diploma

Odysseus Elytis – Banquet speech

Odysseus Elytis’ speech at the Nobel Banquet, December 10, 1979 (in French)

Sire, Madame, Altesses Royales, Mesdames, Messieurs,

Le voyage d’Odysseus, dont il m’a été donné de porter le nom, semble ne devoir jamais s’achever. Et c’est heureux.

Comme l’observait un de nos grands poètes contemporains, l’essentiel n’est pas dans le retour à Ithaque, qui met un terme à presque tout, mais dans l’errance qui est connaissance et aventure. Ce besoin de l’homme de découvrir, de connaître, de s’initier à ce qui le dépasse, est irrépressible. Nous sommes tous captifs de cette soif de connaître ” le miracle “, de croire que le miracle se produit, pourvu que nous y soyons préparés et que nous l’attendions.

En me consacrant, à mon tour, pendant plus de quarante ans, à la poésie, je n’ai rien fait d’autre. Je parcours des mers fabuleuses, je m’instruis en diverses haltes. Et me voici, aujourd’hui, à l’escale de Stockholm avec pour seul capital, dans mes mains, quelques mots helléniques. Ils sont modestes, mais vivants puisqu’ils se trouvent sur les lèvres de tout un peuple.

Ils sont âgés de trois mille ans, mais aussi frais que si l’on venait de les tirer de la mer. Parmi les galets et les algues des rives de l’Egée. Dans les bleus vifs et l’absolue transparence de l’éther. C’est le mot ” ciel “, c’est le mot ” mer “, c’est le mot ” soleil “, c’est le mot ” liberté “. Je les dépose respectueusement à vos pieds. Pour vous remercier. Pour remercier le noble peuple de Suède et ses maîtres à penser qui, en s’opposant à l’estimation quantitative des valeurs, conservent le secret de renouveler chaque année le miracle. Je vous remercie.

Odysseus Elytis – Bibliography

| Major works in Greek |

| Prosanatolizmi, 1940 |

| Ilios o protos, 1943 |

| Asma heroiko kai penthimo gia ton chameno anthypolochago tes Albanias, 1945 |

| To axion esti, 1959 |

| Exi kai mia tipsis yia ton ourano, 1960 |

| Thanatos ke anastasis tou Konstandinou Paleologhou, 1971 |

| To fotodhendro ke i dhekati tetarti omorfia, 1971 |

| Maria Nefeli, 1978 |

| Tria poiemata me simea efkerias, 1982 |

| To imerologio enos atheatou Aprilou, 1984 |

| Ta Demosia ke ta Idiotika, 1990 |

| Ta elegia tis Oxopetras, 1991 |

| Translations into English |

| The Axion Esti by Odysseus Elytis / translated by Edmund Keeley and George Savidis. – University of Pittsburgh Press, 1974 |

| The Sovereign Sun : Selected Poems / translated by Kimon Friar. – Temple University Press, 1974 |

| Maria Nephele : a Poem In Two Voices / translated from the Greek by Athan Anagnostopoulos. – Houghton Mifflin, 1981 |

| Selected Poems / transl. by Edmund Keeley … – Viking Press, 1981 |

| What I Love : Selected Poems of Odysseus Elytis / translated by Olga Broumas. – Copper Canyon Press, 1986 |

| The Little Mariner / translation by Olga Broumas. – Copper Canyon Press, 1988 |

| Open Papers : Selected Essays of Odysseas Elytis / translated by Olga Broumas & T. Begley. – Copper Canyon Press, 1994 |

| The Oxopetra Elegies / translated by David Connolly. – Harwood Academic, 1996 |

| The Collected Poems of Odysseus Elytis / translation by Jeffrey Carson and Nikos Sarris. – Johns Hopkins University Press, 1997 |

| Eros, Eros, Eros : Selected and Last Poems / translation by Olga Broumas. – Copper Canyon Press, 1998 |

| Journal of an Unseen April / translated by David Connolly. – Ypsilon, 1998 |

| Carte Blanche : Selected Writings. – Amsterdam : Harwood Academic, 2000 |

The Swedish Academy, 2006

Odysseus Elytis – Poetry

Excerpt from The Axion Esti

From The Gloria

/- – -/

PRAISED BE Myrto standing

on the stone parapet facing the sea

like a beautiful eight or a clay pitcher

holding a straw hat in her hand

The white and porous middle of day

the down of sleep lightly ascending

the faded gold inside the arcades

and the red horse breaking free

Hera of the tree’s ancient trunk

the vast laurel grove, the light-devouring

a house like an anchor down in the depths

and Kyra-Penelope twisting her spindle

The straits for birds from the opposite shore

a citron from which the sky spilled out

the blue hearing half under the sea

the long-shadowed whispering of nymphs and maples

PRAISED BE, on the remembrance day

of the holy martyrs Cyricus and Julitta,

a miracle burning threshing floors in the heavens

priests and birds chanting the Aye:

HAIL Girl Burning and hail Girl Verdant

Hail Girl Unrepenting, with the prow’s sword

Hail you who walk and the footprints vanish

Hail you who wake and the miracles are born

Hail O Wild One of the depths’ paradise

Hail O Holy One of the islands’ wilderness

Hail Mother of Dreams, Girl of the Open Seas

Hail O Anchor-bearer, Girl of the Five Stars

Hail you of the flowing hair, gilding the wind

Hail you of the lovely voice, tamer of demons

Hail you who ordain the Monthly Ritual of the Gardens

Hail you who fasten the Serpent’s belt of stars

Hail O Girl of the just and modest sword

Hail O Girl prophetic and daedalic

Excerpt from The Axion Esti, by Odysseus Elytis, translated by Edmund Keeley and George Savidis, © 1974.

Reprinted by permission of the University of Pittsburgh Press.

Excerpt selected by the Nobel Library of the Swedish Academy.

Odysseus Elytis – Nobel Lecture

Conference Nobel le 8 decembre 1979

Qu’il me soit permis, je vous en prie, de parler au nom de la luminosité et de la transparence. C’est par ces deux états que se définit l’espace où j’ai vécu et où il m’a été donné de m’accomplir. Etats aussi que j’ai peu à peu perçus comme s’identifiant en moi avec le besoin de m’exprimer.

Il est bon, il est juste qu’apport soit fait à l’art, de ce qu’assignent à chacun son expérience personnelle et les vertus de sa langue. Bien plus encore lorsque les temps sont sombres et qu’il convient d’avoir des choses la plus large vision possible.

Je ne parle pas de la capacité commune et naturelle de percevoir les objets en tous leurs détails, mais du pouvoir de la métaphore de n’en retenir que leur essence, et de les porter à un tel état de pureté que leur signification métaphysique apparaît comme une révélation.

Je pense ici à la façon dont les sculpteurs de la période cycladique firent usage de la matière, parvenant tout juste à la porter au-delà d’elle-même. Je pense aussi aux peintres byzantins d’icônes, qui réussirent, par le seul moyen de la couleur pure, à suggérer le « divin ».

C’est une pareille intervention sur le réel, à la fois pénétrante et métamorphosante, qui a été, de tout temps il me semble, la haute vocation de la poésie. Ne pas se limiter à ce qui est, mais s’étendre à ce qui peut être. Il est vrai que cette démarche n’a pas toujours connu l’estime. Peut-être parce que les névroses collectives ne le permettaient pas. Peut-être encore parce que l’utilitarisme n’autorisait pas les hommes a garder, autant qu’il le fallait, les yeux ouverts.

La Beauté, la Lumière, il arrive qu’on les tienne pour désuètes, pour anodines. Et pourtant! La démarche intérieure qu’exigé l’approche de la forme de l’Ange est, à mon avis, infiniment plus douloureuse que l’autre, qui accouche de Démons de toutes sortes.

Assurément, il y a une énigme. Assurément, il y a un mystère. Mais le mystère n’est pas une mise en scène tirant parti des jeux d’ombre et de lumière pour simplement nous impressionner.

C’est ce qui continue à demeurer mystère même en pleine lumière. C’est alors seulement qu’il prend cet éclat qui séduit et que nous appelons Beauté. Beauté qui est voie ouverte – la seule peut-être – vers cette part inconnue de nous-mêmes, vers ce qui nous dépasse. Voila, cela pourrait être une définition de plus de la poésie: l’art de nous rapprocher de ce qui nous dépasse.

D’innombrables signes secrets dont l’univers est constellé et qui constituent autant de syllabes d’une langue inconnue nous sollicitent de composer des mots, et, avec ces mots, des phrases dont le déchiffrage nous met au seuil de la plus profonde vérité.

Où se trouve donc, en dernière analyse, la vérité? Dans l’usure et la mort que nous constatons chaque jour autour de nous, ou dans cette propension à croire que le monde est indestructible et éternel? Il est sage, je le sais, d’éviter les redondances. Les théories cosmogoniques qui se sont succédé au cours des temps n’ont pas manqué d’en user et d’en abuser. Elles se sont heurtées les unes aux autres, elles ont eu leur temps de gloire, puis elles se sont effacées.

Mais l’essentiel est demeuré. Il demeure.

Et la poésie qui vient se dresser là où le rationalisme dépose ses armes, prend la relève pour avancer dans la zone interdite, faisant ainsi la preuve que c’est elle qui est encore le moins rongée par l’usure. Elle assure, dans la pureté de leur forme, la sauvegarde des données permanentes par quoi la vie demeure œuvre viable. Sans elle et sa vigilance, ces données se perdraient dans l’obscurité de la conscience, tout comme les algues deviennent indistinctes dans le fond des mers.

Voilà pourquoi nous avons grandement besoin de transparence. Pour clairement percevoir les nœuds de ce fil tendu le long des siècles et qui nous aide à nous tenir debout sur cette terre.

Ces nœuds, ces liens, nous les percevons distinctement, d’Heraclite à Platon et de Platon à Jésus. Parvenus jusqu’à nous sous des formes diverses ils nous disent sensiblement la même chose: que c’est à l’intérieur de ce monde-ci qu’est contenu l’autre monde, que c’est avec les éléments de ce monde-ci que se recompose cet autre monde, l’au-delà, cette seconde réalité qui se situe au-dessus de celle que nous vivons contre nature. Il s’agit d’une réalité à laquelle nous avons totalement droit, et seule notre incapacité nous en rend indignes.

Ce n’est pas par rencontre fortuite que, dans les époques saines, le Beau s’identifie au Bien, et le Bien au Soleil. Dans la mesure où la conscience se purifie et s’emplit de lumière, ses parties obscures se rétractent et s’effacent, laissant des vides qui – exactement comme dans les lois physiques – sont comblés par les éléments du sens opposé. Du sorte que ce qui en résulte prend appui sur les deux aspects, je veux dire sur l’ « ici » et sur l’ « au-delà ». Heraclite ne parlait-il pas déjà d’une harmonie des tensions opposées?

Si c’est Apollon ou Vénus, le Christ ou la Vierge qui incarnent et personnalisent le besoin que nous avons de voir matérialiser ce que nous éprouvons comme une intuition, cela n’a pas d’importance. Ce qui est important, c’est ce souffle d’immortalité qui alors nous pénètre. Et à mon humble avis, la Poésie doit, par-delà toute argumentation doctrinale, permettre de respirer ce souffle.

Comment ne pas me référer ici à Hölderlin, ce grand poète qui portait le même regard vers les dieux de l’Olympe et vers le Christ? La stabilité qu’il a donnée à un genre de vision demeure inestimable. Et l’étendue qu’il nous a découverte, immense. Je dirais même terrifiante, (c’est elle qui l’incita à s’écrier – à une époque où commençait à peine le mal qui aujourd’hui nous submerge-: « A quoi bon des poètes en un temps de manque? » Wozu. Dichter in dürftiger Zeit?

Pour l’homme, les temps furent toujours, hélas, dürftig. Mais la poésie n’a jamais, d’autre part, manqué à sa vocation. C’est là deux faits qui ne cesseront jamais d’accompagner notre destinée terrestre, l’un servant de contre-poids à l’autre. Comment pourrait-il en être autrement? C’est par le Soleil que la nuit et les astres nous sont perceptibles. Notons toutefois, avec le sage antique, que s’il dépasse la mesure, le Soleil devient ![]() .Pour que la vie soit possible, nous devons nous tenir à une juste distance du soleil figuré, comme notre planète du soleil naturel. Nous fûmes jadis en faute par ignorance. Nous fautons aujourd’hui par l’étendue de notre savoir. Je ne viens pas, en disant cela, me joindre à la longue file des censeurs de notre civilisation technique. Une sagesse aussi ancienne que le pays d’où je viens m’a enseigné d’ accepter l’évolution, à digérer le progrès « avec ses écorces et ses noyaux ».

.Pour que la vie soit possible, nous devons nous tenir à une juste distance du soleil figuré, comme notre planète du soleil naturel. Nous fûmes jadis en faute par ignorance. Nous fautons aujourd’hui par l’étendue de notre savoir. Je ne viens pas, en disant cela, me joindre à la longue file des censeurs de notre civilisation technique. Une sagesse aussi ancienne que le pays d’où je viens m’a enseigné d’ accepter l’évolution, à digérer le progrès « avec ses écorces et ses noyaux ».

Mais alors, qu’advient-il de la Poésie? Que représente-t-elle dans pareille société? Voici ce que j’ai à répondre: La poésie est le seul lieu où la puissance du nombre s’avère nulle. Et votre décision d’honorer, cette année, en ma personne, la poésie d’un petit pays, révèle le rapport d’harmonie qui la lie à la conception de l’art gratuit, seule conception à s’opposer désormais à la toute-puissance acquise par l’estimation quantitative des valeurs.

Me référer à des circonstances personnelles serait manquer aux convenances. Et faire l’éloge de ma maison, plus inconvenant encore. Cela est néanmoins parfois indispensable, dans la mesure où pareilles interférences aident à voir plus clairement un certain état de choses. C’est bien le cas aujourd’hui.

Il m’a été donné, chers amis, d’écrire dans une langue qui n’est parlée que par quelques millions de personnes. Mais une langue parlée sans interruption, avec fort peu de différences, tout au cours de plus de deux mille cinq cents ans. Cet écart spatio-temporel, apparemment surprenant, se retrouve dans les dimensions culturelles de mon pays. Son aire spatiale est des plus réduites; mais son extension temporelle infinie. Si je le rappelle, ce n’est certes pas pour en tirer quelque fierté, mais pour montrer les difficultés que doit affronter un poète lorsqu’il doit faire usage, pour nommer les choses qui lui sont les plus chères, des mêmes mots que Sappho par exemple ou Pindare, tout en étant privés de l’audience dont ils disposaient et qui s’étendait, alors, à toute l’humanité civilisée.

Si la langue n’était qu’un simple moyen de communication, il n’y aurait pas de problème. Mais il arrive, parfois, qu’elle soit aussi un instrument de « magie ». De plus, dans ce long cours de siècles, la langue acquiert une certaine manière d’être. Elle devient un haut langage. Et cette manière d’être oblige.

N’oublions pas non plus qu’en chacun de ces vingt-cinq siècles et sans nulle béance, il s’est écrit, en grec, de la poésie. C’est cet ensemble de données qui fait le grand poids de tradition que cet instrument soulève. La poésie grecque moderne en donne une image fort expressive.

La sphère que forme cette poésie, présente, pourrait-on dire, comme toute sphère, deux pôles: A l’un de ces pôles se situe Dionysios Solomos, qui, avant que Mallarmé n’apparaisse dans les lettres européennes, réussit à formuler, avec la plus grande rigueur et cohérence, ainsi que dans toutes ses conséquences, la conception de la poésie pure: soumettre le sentiment à l’intelligence, anoblir l’expression, mobiliser toutes les possibilités de l’instrument linguistique en s’orientant vers le miracle. A l’autre pôle se situe Cavafis, qui, parallèlement à T.S. Eliot, atteint, éliminant toute forme de boursouflure, à l’extrême limite de la concision et à l’expression la plus rigoureusement exacte.

Entre ces deux pôles, et plus ou moins près de l’un ou de l’autre, se meuvent nos autres grands poètes: Costis Palamas, Anguélos Sikkelianos, Nikos Kazantzakis, Georges Seferis.

Tel est, aussi rapidement que schématiquement tracé, le tableau du discours poétique néo-hellénique.

Pour nous qui avons suivi, nous avions à prendre en charge le haut enseignement qui nous avait été légué et à l’adapter à la sensibilité contemporaine. Par-delà les bornes de la technique, il nous fallait parvenir à une synthèse qui, d’une part, assimilât les éléments de la tradition grecque et, de l’autre, exprimât les exigences sociales et psychologiques de notre temps.

En d’autres termes, nous avions à saisir dans sa vérité l’Européen-Grec d’aujourd’hui et à la faire valoir. Je ne parle pas de réussites, je parle d’intentions, d’efforts. Les orientations ont leur importance pour l’investigation de l’histoire littéraire.

Mais comment la création peut-elle se développer librement dans ces directions lorsque les conditions de vie anéantissent, de nos jours, le créateur? Et comment créer une communauté culturelle lorsque la diversité des langues dresse un obstacle infranchissable? Nous vous connaissons et vous nous connaissez par les 20 ou 30 % qui subsistent d’une œuvre, après traduction. Cela est encore plus vrai pour tous ceux d’entre nous qui, prolongeant le sillon tracé par Solomos attendent du discours quelque miracle et qu’entre deux mots, sonnant juste et placés à leur juste place, jaillisse l’étincelle.

Non. Nous demeurons muets, incommunicables.

Nous souffrons de l’absence d’une langue commune. Et les conséquences de cette absence s’observent – je ne crois pas exagérer – jusque dans la réalité politique et sociale de notre patrie commune, l’Europe.

Nous disons – et en faisons chaque jour la constatation – que nous vivons dans un chaos moral. Et cela à un moment où – chose qui ne s’était jamais vue – la répartition de ce qui concerne notre existence matérielle est faite de la façon la plus systématique, dans un ordre qu’on pourrait dire militaire, avec d’implacables contrôles. Cette contradiction est significative. Lorsque, de deux membres, l’un s’hypertrophie, l’autre s’atrophie. Une tendance digne d’éloge, qui incite les peuples d’Europe à s’unir, au sens pythagoricien, en une seule monade, se heurte aujourd’hui à l’impossibilité d’harmonier les parties atrophiques et hypertrophiques de notre civilisation. Nos valeurs ne constituent pas une langue commune.

Pour le poète – cela peut paraître paradoxal mais c’est vrai – la seule langue commune dont il a encore l’usage, ce sont ses sensations. La façon dont deux corps s’attirent et s’attouchent n’a pas changé depuis des millénaires. Et en plus, elle n’a donné lieu à aucun conflit, contrairement aux vingtaines d’idéologies qui ont ensanglanté nos sociétés et nous ont laissé les mains vides.

Lorsque je parle de sensations, je n’entends pas celles, immédiatement perceptibles, du premier ou du second niveau. J’entends celles qui nous portent à l’extrême bord de nous-mêmes. J’entends aussi les “analogies de sensations” qui se forment dans nos esprits.

Car tous les arts parlent par analogies. Une ligne, droite ou courbe, un son aigu ou grave, traduisent un certain contact optique ou acoustique. Nous écrivons tous de bons ou de mauvais poèmes dans la mesure où nous vivons ou raisonnons selon la bonne ou la mauvaise signification du terme. Une image de la mer, telle que nous la trouvons dans Homère, parvient intacte jusqu’à nous. Rimbaud dira “une mer mêlée au soleil”. Sauf que lui ajoutera: “c’est là l’éternité.” Une jeune fille tenant une branche de myrte chez Archiloque survit dans un tableau de Matisse. Et l’idée méditerranéenne de pureté nous est ainsi rendue plus tangible. D’ailleurs, l’image d’une vierge de l’iconographie byzantine est-elle si différente de celle de ses sœurs profanes? Il suffit de bien peu de chose pour que la lumière de ce monde se transforme en clarté surnaturelle, et inversement. Une sensation héritée des anciens et une autre que nous a léguée le Moyen Age en engendrent une troisième qui leur ressemble, comme un enfant à ses parents. La poésie peut-elle suivre une telle voie? Les sensations peuvent-elles, au terme de cet incessant processus de purification, parvenir à un état de sainteté? Elles reviendront alors, analogies, se greffer sur le monde matériel et agir sur lui.

Il ne suffit pas de mettre nos rêves en vers. C’est trop peu. Il ne suffit pas de politiser nos propos. C’est trop. Le monde matériel n’est au fond qu’un amas de matériaux. A nous de nous montrer bons ou mauvais architectes, d’édifier le Paradis, ou l’Enfer. C’est cela que ne cesse de nous affirmer la poésie – et particulièrement en ces temps dürftiger – cela précisément: que notre destin malgré tout repose entre nos mains.

J’ai souvent tenté de parler de métaphysique solaire. Je n’essayerai pas aujourd’hui d’analyser de quelle façon l’art se trouve impliqué dans une telle conception. Je m’en tiens à un seul et simple fait: le langage des grecs, en tant qu’instrument magique, entretient avec le soleil – réalité ou symbole – des relations intimes. Et ce soleil n’inspire pas seulement une certaine attitude de vie, et donc son sens premier au poème. Il pénètre sa composition, sa structure, et – pour utiliser une terminologie actuelle – ce nucleus duquel se compose la cellule que nous appelons poème.

Ce serait une erreur de croire qu’il sagit là d’un retour à la notion de forme pure. Le sens de la forme, tel que nous l’a légué l’Occident, est un acquis constant, représenté par trois ou quatre modèles. Trois ou quatre moules pourrait-on dire où il convenait de couler à tout prix la matière la plus hétéroclite. Aujourd’hui cela n’est plus concevable. J’ai été l’un des premiers en Grèce à briser ces liens.

Ce qui m’intéressait, obscurément au début, puis de plus en plus consciemment, c’était l’édification du matériau selon un mode architectural chaque fois différent. Il n’est pas besoin pour comprendre cela de se référer à la sagesse des anciens qui conçurent les Parthénons. Il suffit d’évoquer les humbles bâtisseurs de nos maisons et de nos chapelles des Cyclades, trouvant, en chaque occasion, la solution la meilleure. Leurs solutions. Pratiques et belles à la fois, telles enfin que, les voyant, un Le Corbusier ne put qu’admirer et s’incliner.

Peut-être est-ce cet instinct qui s’éveilla en moi lorsque, pour la première fois, il me fallut affronter une grande composition comme le « Axion Esti ». Je compris alors que faute de lui donner les proportions et la perspective d’un édifice, elle n’atteindrait jamais la solidité que je souhaitais.

Je suivis l’exemple de Pindare ou du byzantin Romanos Mélodos qui, pour chacune de leurs odes, ou de leurs cantiques, inventaient chaque fois un mode toujours nouveau. Je vis que la répétition déterminée, à intervalles, de certains éléments de versification donnait effectivement à mon ouvrage cette substance aux facettes multiples et pourtant symétriques qui était mon projet.

Mais alors n’est-il pas vrai que le poème, ainsi entouré d’éléments qui gravitent autour de lui, se transforme en un petit soleil? Cette correspondance parfaite, que je trouve ainsi obtenue, avec le contenu pensé, est, je le crois, l’idéal le plus élevé du poète.

Tenir entre les mains le soleil sans se brûler, le transmettre aux suivants comme un flambeau, est un acte douloureux, mais, je le crois, béni. Nous en avons besoin. Un jour les dogmes qui enchaînent les hommes s’effaceront devant la conscience inondée de lumière, tant qu’elle ne fera plus qu’un avec le soleil, et qu’elle abordera aux rives idéales de la dignité humaine et de la liberté.

* Disclaimer

Every effort has been made by the publisher to credit organizations and individuals with regard to the supply of audio files. Please notify the publishers regarding corrections.

Odysseus Elytis – Nobel Lecture

English

Nobel Lecture, December 8, 1979

(Translation)

May I be permitted, I ask you, to speak in the name of luminosity and transparency. The space I have lived in and where I have been able to fulfill myself is defined by these two states. States that I have also perceived as being identified in me with the need to express myself.

It is good, it is right that a contribution be made to art, from that which is assigned to each individual by his personal experience and the virtues of his language. Even more so, since the times are dismal and we should have the widest possible view of things.

I am not speaking of the common and natural capacity of perceiving objects in all their detail, but of the power of the metaphor to only retain their essence, and to bring them to such a state of purity that their metaphysical significance appears like a revelation.

I am thinking here of the manner in which the sculptors of the Cycladic period used their material, to the point of carrying it beyond itself. I am also thinking of the Byzantine icon painters, who succeeded, only by using pure color, to suggest the “divine”.

It is just such an intervention in the real, both penetrating and metamorphosing, which has always been, it seems to me, the lofty vocation of poetry. Not limiting itself to what is, but stretching itself to what can be. It is true that this step has not always been received with respect. Perhaps the collective neuroses did not permit it. Or perhaps because utilitarianism did not authorize men to keep their eyes open as much as was necessary.

Beauty, Light, it happens that people regard them as obsolete, as insignificant. And yet! The inner step required by the approach of the Angel’s form is, in my opinion, infinitely more painful than the other, which gives birth to Demons of all kinds.

Certainly, there is an enigma. Certainly, there is a mystery. But the mystery is not a stage piece turning to account the play of light and shadow only to impress us.

It is what continues to be a mystery, even in bright light. It is only then that it acquires that refulgence that captivates and which we call Beauty. Beauty that is an open path – the only one perhaps – towards that unknown part of ourselves, towards that which surpasses us. There, this could be yet another definition of poetry: the art of approaching that which surpasses us.

Innumerable secret signs, with which the universe is studded and which constitute so many syllables of an unknown language, urge us to compose words, and with words, phrases whose deciphering puts us at the threshold of the deepest truth.

In the final analysis, where is truth? In the erosion and death we see around us, or in this propensity to believe that the world is indestructible and eternal? I know, it is wise to avoid redundancies. The cosmogonic theories that have succeeded each other through the years have not missed using and abusing them. They have clashed among themselves, they have had their moment of glory, then they have been erased.

But the essential has remained. It remains.

The poetry that raises itself when rationalism has laid down its arms, takes its relieving troops to advance into the forbidden zone, thus proving that it is still the less consumed by erosion. It assures, in the purity of its form, the safeguard of those given facts through which life becomes a viable task. Without it and its vigilance, these given facts would be lost in the obscurity of consciousness, just as algae become indistinct in the ocean depths.

That is why we have a great need of transparency. To clearly perceive the knots of this thread running throughout the centuries and aiding us to remain upright on this earth.

These knots, these ties, we see them distinctly, from Heraclitus to Plato and from Plato to Jesus. Having reached us in various forms they tell us the same thing: that it is in the inside of this world that the other world is contained, that it is with the elements of this world that the other world is recombined, the hereafter, that second reality situated above the one where we live unnaturally. It is a question of a reality to which we have a total right, and only our incapacity makes us unworthy of it.

It is not a coincidence that in healthy times, Beauty is identified with Good, and Good with the Sun. To the extent that consciousness purifies itself and is filled with light, its dark portions retract and disappear, leaving empty spaces – just as in the laws of physics – are filled by the elements of the opposite import. Thus what results of this rests on the two aspects, I mean the “here” and the “hereafter”. Did not Heraclitus speak of a harmony of opposed tensions?

It is of no importance whether it is Apollo or Venus, Christ or the Virgin who incarnate and personalize the need we have to see materialized what we experience as an intuition. What is important is the breath of immortality that penetrates us at that moment. In my humble opinion, Poetry should, beyond all doctrinal argumentation, permit this breath.

Here I must refer to Hölderlin, that great poet who looked at the gods of Olympus and Christ in the same manner. The stability he gave a kind of vision continues to be inestimable. And the extent of what he has revealed for us is immense. I would even say it is terrifying. It is what incites us to cry out – at a time when the pain now submerging us was just beginning – : “What good are poets in a time of poverty”. Wozu Dichter in dürftiger Zeit?

For mankind, times were always dürftig, unfortunately. But poetry has never, on the other hand, missed its vocation. These are two facts that will never cease to accompany our earthly destiny, the first serving as the counter-weight to the other. How could it be otherwise? It is through the Sun that the night and the stars are perceptible to us. Yet let us note, with the ancient sage, that if it passes its bounds the Sun becomes “![]() “. For life to be possible, we have to keep a correct distance to the allegorical Sun, just as our planet does from the natural Sun. We formerly erred through ignorance. We go wrong today through the extent of our knowledge. In saying this I do not wish to join the long list of censors of our technological civilization. Wisdom as old as the country from which I come has taught me to accept evolution, to digest progress “with its bark and its pits”.

“. For life to be possible, we have to keep a correct distance to the allegorical Sun, just as our planet does from the natural Sun. We formerly erred through ignorance. We go wrong today through the extent of our knowledge. In saying this I do not wish to join the long list of censors of our technological civilization. Wisdom as old as the country from which I come has taught me to accept evolution, to digest progress “with its bark and its pits”.

But then, what becomes of Poetry? What does it represent in such a society? This is what I reply: poetry is the only place where the power of numbers proves to be nothing. Your decision this year to honor, in my person, the poetry of a small country, reveals the relationship of harmony linking it to the concept of gratuitous art, the only concept that opposes nowadays the all-powerful position acquired by the quantitative esteem of values.

Referring to personal circumstances would be a breach of good manners. Praising my home, still more unsuitable. Nevertheless it is sometimes indispensable, to the extent that such interferences assist in seeing a certain state of things more clearly. This is the case today.

Dear friends, it has been granted to me to write in a language that is spoken only by a few million people. But a language spoken without interruption, with very few differences, throughout more than two thousand five hundred years. This apparently surprising spatial-temporal distance is found in the cultural dimensions of my country. Its spatial area is one of the smallest; but its temporal extension is infinite. If I remind you of this, it is certainly not to derive some kind of pride from it, but to show the difficulties a poet faces when he must make use, to name the things dearest to him, of the same words as did Sappho, for example, or Pindar, while being deprived of the audience they had and which then extended to all of human civilization.

If language were not such a simple means of communication there would not be any problem. But it happens, at times, that it is also an instrument of “magic”. In addition, in the course of centuries, language acquires a certain way of being. It becomes a lofty speech. And this way of being entails obligations.

Let us not forget either that in each of these twenty-five centuries and without any interruption, poetry has been written in Greek. It is this collection of given facts which makes the great weight of tradition that this instrument lifts. Modern Greek poetry gives an expressive image of this.

The sphere formed by this poetry shows, one could say, two poles: at one of these poles is Dionysios Solomos, who, before Mallarmé appeared in European literature, managed to formulate, with the greatest rigor and coherency, the concept of pure poetry: to submit sentiment to intelligence, ennoble expression, mobilize all the possibilities of the linguistic instrument by orienting oneself to the miracle. At the other pole is Cavafy, who like T. S. Eliot reaches, by eliminating all form of turgidity, the extreme limit of concision and the most rigorously exact expression.

Between these two poles, and more or less close to one or the other, our other great poets move: Kostis Palamas, Angelos Sikelianos, Nikos Kazantzakis, George Seferis.

Such is, rapidly and schematically drawn, the picture of neo-Hellenic poetic discourse.

We who have followed have had to take over the lofty precept which has been bequeathed to us and adapt it to contemporary sensibility. Beyond the limits of technique, we have had to reach a synthesis, which, on the one hand, assimilated the elements of Greek tradition and, on the other, the social and psychological requirements of our time.

In other words, we had to grasp today’s European-Greek in all its truth and turn that truth to account. I do not speak of successes, I speak of intentions, efforts. Orientations have their significance in the investigation of literary history.

But how can creation develop freely in these directions when the conditions of life, in our time, annihilate the creator? And how can a cultural community be created when the diversity of languages raises an unsurpassable obstacle? We know you and you know us through the 20 or 30 per cent that remains of a work after translation. This holds even more true for all those of us who, prolonging the furrow traced by Solomos, expect a miracle from discourse and that a spark flies from between two words with the right sound and in the right position.

No. We remain mute, incommunicable.

We are suffering from the absence of a common language. And the consequences of this absence can be seen – I do not believe I am exaggerating – even in the political and social reality of our common homeland, Europe.

We say – and make the observation each day – that we live in a moral chaos. And this at a moment when – as never before – the allocation of that which concerns our material existence is done in the most systematic manner, in an almost military order, with implacable controls. This contradiction is significant. Of two parts of the body, when one is hypertrophic, the other atrophies. A praise-worthy tendency, encouraging the peoples of Europe to unite, is confronted today with the impossibility of harmonization of the atrophied and hypertrophic parts of our civilization. Our values do not constitute a common language.

For the poet – this may appear paradoxical but it is true – the only common language he still can use is his sensations. The manner in which two bodies are attracted to each other and unite has not changed for millennia. In addition, it has not given rise to any conflict, contrary to the scores of ideologies that have bloodied our societies and have left us with empty hands.

When I speak of sensations, I do not mean those, immediately perceptible, on the first or second level. I mean those which carry us to the extreme edge of ourselves. I also mean the “analogies of sensations” that are formed in our spirits.

For all art speaks through analogy. A line, straight or curved, a sound, sharp or low-pitched, translate a certain optical or acoustic contact. We all write good or bad poems to the extent that we live or reason according to the good or bad meaning of the term. An image of the sea, as we find it in Homer, comes to us intact. Rimbaud will say “a sea mixed with sun”. Except he will add: “that is eternity.” A young girl holding a myrtle branch in Archilochus survives in a painting by Matisse. And thus the Mediterranean idea of purity is made more tangible to us. In any case, is the image of a virgin in Byzantine iconography so different from that of her secular sisters? Very little is needed for the light of this world to be transformed into supernatural clarity, and inversely. One sensation inherited from the Ancients and another bequeathed by the Middle Ages give birth to a third, one that resembles them both, as a child does its parents. Can poetry survive such a path? Can sensations, at the end of this incessant purification process, reach a state of sanctity? They will return then, as analogies, to graft themselves on the material world and to act on it.

It is not enough to put our dreams into verse. It is too little. It is not enough to politicize our speech. It is too much. The material world is really only an accumulation of materials. It is for us to show ourselves to be good or bad architects, to build Paradise or Hell. This is what poetry never ceases affirming to us – and particularly in these dürftiger times – just this: that in spite of everything our destiny lies in our hands.

I have often tried to speak of solar metaphysics. I will not try today to analyse how art is implicated in such a conception. I will keep to one single and simple fact: the language of the Greeks, like a magic instrument, has – as a reality or a symbol – intimate relations with the Sun. And that Sun does not only inspire a certain attitude of life, and hence the primeval sense to the poem. It penetrates the composition, the structure, and – to use a current terminology – the nucleus from which is composed the cell we call the poem.

It would be a mistake to believe that it is a question of a return to the notion of pure form. The sense of form, as the West has bequeathed it to us, is a constant attainment, represented by three or four models. Three or four moulds, one could say, where it was suitable to pour the most anomalous material at any price. Today that is no longer conceivable. I was one of the first in Greece to break those ties.

What interested me, obscurely at the beginning, then more and more consciously, was the edification of that material according to an architectural model that varied each time. To understand this there is no need to refer to the wisdom of the Ancients who conceived the Parthenons. It is enough to evoke the humble builders of our houses and of our chapels in the Cyclades, finding on each occasion the best solution. Their solutions. Practical and beautiful at the same time, so that in seeing them Le Corbusier could only admire and bow.

Perhaps it is this instinct that woke in me when, for the first time, I had to face a great composition like “Axion Esti.” I understood then that without giving the work the proportions and perspective of an edifice, it would never reach the solidity I wished.

I followed the example of Pindar or of the Byzantine Romanos Melodos who, in each of their odes or canticles, invented a new mode for each occasion. I saw that the determined repetition, at intervals, of certain elements of versification effectively gave to my work that multifaceted and symmetrical substance which was my plan.

But then is it not true that the poem, thus surrounded by elements that gravitate around it, is transformed into a little Sun? This perfect correspondence, which I thus find obtained with the intended contents, is, I believe, the poet’s most lofty ideal.

To hold the Sun in one’s hands without being burned, to transmit it like a torch to those following, is a painful act but, I believe, a blessed one. We have need of it. One day the dogmas that hold men in chains will be dissolved before a consciousness so inundated with light that it will be one with the Sun, and it will arrive on those ideal shores of human dignity and liberty.

Odysseus Elytis – Other resources

Links to other sites

On Odysseus Elytis from Pegasos Author’s Calendar

Odysseus Elytis – Facts

Press release

Swedish Academy

The Permanent Secretary

Press release

The Nobel Prize in Literature 1979

Odysseus Alepoudhélis (pseudonym Odysseus Elytis)

Odysseus Elytis’s name tells us a great deal about him as a person and a writer.

Odysseus – the seafarer, the Homeric poem’s hero, alive with the spirit of freedom, with defiant intrepidity, enterprise, and an insatiable appetite for all the adventures and sensuous experiences that the seas and isles of Greece can offer. Odysseus is the name given to the poet by his parents. It testifies to the feeling for the past and to the links with the myths and distinctive character of Greek tradition. The family comes from the Aegean islands. The poet was born in Crete just before the liberation from Turkish rule.

Elytis is the name he adopted at the very beginning of his career as a writer. The name is a composite one, with allusion to several concepts dear to the poet’s heart – it could be called a much abridged manifesto. The components in the name are to serve as a reminder of the Greek words for Greece (Ellas), hope (elpídha), freedom (elefthería) and the mythical woman who is the personification of beauty, erotic sensuality and female allure, Helena (Eléni). Eros and Heros are closely connected in Elytis’s world of poetry or myth.

The sea and the islands, their fauna and flora, the smooth pebbles on the beaches, the surge of the waves, the prickly black sea-urchins, the tang of salt, and the light over the water are constantly recurring elements in his writing – like the bright flood of sunlight which baptizes this world with its all-pervading lustre, at once fertile and purifying. Sensuality and light irradiate Elytis’s poetry. The perceptible world is vividly present and overwhelming in its wealth of freshness and astonishing experiences.

But through Elytis’s evocative verbal art, this world is also elevated to a symbolic reality. It becomes an ideal for the world that is not always so bright and true and wonderful, but which should be, and could be. We should always praise and worship this world for what it ought to be, and for what it, thereby, can be to us: a life-giving source of strength. Elytis’s extolling of existence, of man and his potentialities, and life in communion with the rest of creation, is no idealizing or illusory escapism. It is a moral act of invocation of the kind to be found so many times in Greek history, from the present-day struggles for freedom against fascist or other oppression far back through the centuries to the heroic phase of the classical era. What matters is not to submit. What matters is constantly to bear in mind what life should be, and what man can shape for himself in defiance of all that threatens to destroy him and violate him.

This is not political writing in the narrow sense of the word. It is a writing of preparedness, which aims at defending the moral integrity or pride that is essential if we are to be able to resist at all, and to endure hardships and dangers, outrage and adversity. These sides of Elytis’s poetry emerged strongly during the first years of the 1940s when he took part in the campaign in Albania against the fascist invasion. He passed through what he himself calls a crisis. Everything had to be tried out afresh – how to live, what the use of poetry was, how the beauty of poetry and art could serve in the fight for human dignity and resistance, yet preserve its freedom as art.

The poem, Heroic and Elegiac Song for the Lost Second Lieutenent of the Albanian Campaign was written during this war, most of it based on personal experience. It immediately evoked response and became a kind of generation document for the young. It has kept its position as an expression of the Greeks’ indomitable spirit of resistance. The fallen soldier is a representative of the Greeks who were killed in this war, but also of all those who have fallen during Greece’s long history of struggle for national liberty and individuality. Here, as so often in Elytis’s writing, realistic and mythical depiction are combined.

The Albanian campaign and the “heroic and elegiac song” about it were, in a way, a turning point for Elytis as a poet. His first verses had been published in the middle of the 1930s in a magazine which was then a forum for young writers, Nea Ghrámmata — in fact, a school for budding poets. The impulses from French surrealism, in particular, made themselves felt – in Elytis’s case, chiefly from Paul Éluard. Surrealism became a liberator. It helped the young writers to find themselves, not least, in relation to the great Greek classical tradition, which might threaten to become oppressive and to stagnate in stereotyped and rhetorical formulae. Elytis’s first poems, before Heroic and Elegiac Song, are youthfully sensual, full of light, brilliant, and very evocative in their visual and charming freshness. They quickly established him as one of the leading new Greek poets.

With Herioc and Elegiac Song, however, other sides of the writer emerged and insisted on becoming part of his creative world – sides which had been there from the outset but which now demanded more room: the tragic and the heroic. In the poetic cycle which many regard as Elytis’s foremost work, To áxion estí (Worthy It Is ), these very complex experiences and programs have been given a form which makes this work one of 20th century literature’s most concentrated and richly-faceted poems. The cycle is a kind of lyric drama or myth with strains from Hesiod, the Bible and Byzantine hymns. In its severe and polyphonic structure it is also linked to the avant-gardism of modern western writing. The cycle begins almost as drama of creation, concerning not only the poet himself, but, through him, us all. For, Elytis says, “I do not speak about myself. I speak for anyone who feels like myself but does not have enough naiveté to confess it.” But it is also about the origin of Greece, in fact of the world. Then follows an architecturally complicated section with descriptions of the war and other scourges that have afflicted Greece and modern man. After this section, which represents a crisis or path of suffering, comes a concluding part, the actual song of praise; mature man is tempered and strengthened through his experiences but also fortified in his indomitable and defiant will to defend life and its sensuous abundance.

In one of his short essays, Elytis sums up his intentions: “I consider poetry a source of innocence full of revolutionary forces. It is my mission to direct these forces against a world my conscience cannot accept, precisely so as to bring that world through continual metamorphoses more in harmony with my dreams. I am referring here to a contemporary kind of magic whose mechanism leads to the discovery of our true reality. It is for this reason that I believe to the point of idealism, that I am moving in a direction which has never been attempted until now. In the hope of obtaining a freedom from all constraints, and the justice which could be identified with absolute light…”

In its combination of fresh, sensuous flexibility and strictly disciplined implacability in the face of all compulsion, Elytis’s poetry give a shape to its distinctiveness,which is not only very personal but also represents the traditions of the Greek people.

Bio-bibliographical notes

Odysseus Elytis, pen-name for Odysseus Alepoudhiéis, was born in 1911 at Herakleion in Crete. The family, which originally came from Lesbos, moved in 1914 to Athens, where Elytis, after leaving school, began to read law. He broke off his studies, however, and devoted himself entirely to his literary and artistic interests. He got to know the foremost advocate in Greece of surrealism, the poet Andreas Embirikos, who became his lifelong friend. As time went on impulses from Embirikos and others became merged with Elytis’ Greek-Byzantine cultural tradition. In 1935 he published his first poems in the magazine Nea Ghrámmata (New Letters) and also took part – with collages – in the first international surrealist exhibition arranged that year in Athens. In 1936 and 1937, in the magazine Makedhonikés Iméres (Macedonian Days) followed a collection of poems with the title Prosanatolizmoí (Orientations), in book form 1939, I klepsídhres tou aghnóstou (Hourglass of the Unknown) and, in 1943, Ilios o prótos (Sun the First).

Deeply felt experiences from the war lie behind the work that made Elytis famous as one of the most prominent poets of the Greek resistance and struggle for freedom: Ásma iroikó ke pénthimo yia ton haméno anthipolohaghó tis Alvanías (Heroic and Elegiac Song for the Lost Second Lieutenant of the Albanian Campaign) 1945.

After the war Elytis was engaged in various public assignments (among other things he was head of programs at the radio) and, apart from literary and art criticism, published very little for more than ten years. The work begun in 1948, To Áxion Estí (Worthy It Is), did not appear until 1959. The years 1948-52 he spent in Paris and travelling. He came in close contact with writers like Breton, Eluard, Char, Jouve and Michaux and with artists such as Matisse, Picasso and Giacometti. The poetic cycle To Áxion Estí (with introductory words taken from the Greek-Orthodox liturgy) has come to be recognized as Elytis’s greatest work. It has been translated into several languages and in 1960 was awarded the National Prize in Poetry. It was set to music by Míkis Theodorákis in 1964.

Of later works – in several cases illustrated by the author himself or by his friends Picasso, Matisse, Ghika, Tsarouchis and others – can be mentioned: Exi ke miá típsis yia ton uranó (Six and One Remorses for the Sky) 1960, O ílios o iliátoras (The Sovereign Sun) and To monoghramma (The Monogram), both 1971, Ta ro tou érota (The Ro of Eros) 1972, Villa Natacha 1973, Maria Neféli 1979, and the collection of essays with a personal touch Anihtá hártia (Open Book) 1974. “Selected Writings;” (with collages by the author) recently appeared, and no less than three entirely new works await publication.

For many years past translations of Elytis’s poems have been printed in literary magazines and anthologies, but are also to be had in a number of separate volumes:

In English:

The Sovereign Sun: Selected poems. Kimon Friar, transl. Philadelphia: Temple Univ. Press, 1974.

The Axion Esti (bilingual ed.) Edmund Keeley Georges Savidis, transl. Pittsburgh: Univ. of Pittsburgh Press, 1974.

In French:

Six plus un remords pour le ciel. Texte francais de F.B. Mache. Montpellier: Fata Morgana, 1977.

In Italian:

Poesie. Trad. Mario Vitti. Roma 1952.

21 poesie. Trad. Vincenzo Rotolo. Palermo: Ist. Siciliano di Studi Bizantini e Neoellenici, 1968.

In German:

Korper des Sommers. Auagewahlte Gedichte. Neugriechisch u. deutsch. Uebertr. Antigone Kasolea u. Barbara Schlorb. St. Gallen: Tschudy Verlag 1960.

Sieben nachtliche Siebeneeiler. Griechisch-Deutsch. Uebertr. Gunter Dietz. Darmstadt: J.G. Blaschke Verlag, 1966.

To Axion Esti-Gepriesen Sei.Uebetr. Gunter Dietz. Hamburg: Claassen Verlag, 1969.

As well as in most of the above works Elytis is presented in detail in the magazine Books Abroad (Univ. of Oklahoma), vol. 49 (1975), No. 4 (Autumn).

Award ceremony speech

Presentation Speech by Doctor Karl Ragnar Gierow, of the Swedish Academy.

Translation from the Swedish text

Your Majesties, Your Royal Highnesses, Ladies and Gentlemen,

When Giorgos Seferis, compatriot of this year’s Nobel prizewinner in literature, came here in 1963 to receive the same award, he presented at the airport a bunch of hyacinths each to the then Secretary of the Swedish Academy and to its officiating director that winter as a greeting to their respective wives. He had picked them himself on Hymettus, the mountain a few miles east of Athens where Aphrodite had her miraculous spring and where, ever since antiquity, hyacinths grow wild in a profusion which makes the whole mountain smell of honey.

The episode comes naturally to mind now that we have the pleasure of welcoming Odysseus Elytis, the Greek writer who in his youth made his name with the collection The Concert of Hyacinths, in which he calls to his beloved: “Take with you the light of hyacinths and baptize it in the wellspring of day” and assures her that “when you glitter in the sun that on you glides waterdrops, and deathless hyacinths, and silences, I proclaim you the only reality.”

But there is a more immediate reason today to think of the chivalrous gesture in the inhospitable sleet of the airport. The hyacinths Seferis gave us were not at all like those we are accustomed to see. And, freshly picked as they were, they became symbols not only of the climatic difference between the giver’s sunny south and our snowy north. If Odysseus Elytis, the author of The Concert of Hyacinths, had wished to use that flower as one of the analogies between environment and perception that are an essential part of his cultural outlook, he could have said that our potplants are a west-European rationalization of something which in his country grows wild, thereby acquiring its everlasting beauty. To this beauty he has devoted most of what he has written, and a recurrent theme is the prevalent west-European misconception of all that goes to make up the distinctive world of ideas whose legitimate heir he is.

He has arrived at his critical view of our all too rationalistic picture of Greece, which he traces back to the Renaissance’s ideal of antiquity, by his own familiarity with western Europe’s poetry, art and way of thinking. It may seem like a paradox – one which he himself has pointed out-that it was this western Europe, branded by him for its sterile rationalism, which gave Elytis the impulse that all at once set free his own writing: surrealism, which cannot be said to exaggerate reason.

The paradox is, if not apparent, at any rate not entirely unusual. Like a rebellious pulse of exuberant life surrealism broke through the hardened arteries of calcified forms. Outside France too poetry was dominated by a school which called itself “Les Parnassiens” but which never reached even the foot of Parnassus, if we share Elytis’s view of what Greece has been and still is. But also on the Greek Parnassus of that time sat the same connoisseurs of degeneration who, in ornate words, declared their pessimistic conviction that nothing in this world was worth anything except their ability to express perfectly this very thought. If such an atmosphere is to be called captivating, surrealism came as a liberation, a religious revival, even if the sign of the saved here and there was a mere speaking with tongues.

But much of the best that happens when an art form is rejuvenated is not the result of a definite program but the fruit of an unforeseen cross. For Greek poetry the contact with surrealism meant a flowering which allows us to call the last fifty years Hellas’s second highwater mark. In none of the numerous important poets who have created this age of greatness can we see more clearly than in Elytis what this vigorous cross signified: the exciting meeting between epoch-making modernism and inherited myth.

A cursory presentation of a poet hard to understand should, then, first establish his relationship to these two components – surrealism and myth. The task is not as easy as it looks. We have his own word for it: “I considered surrealism,” he says on the one hand, “as the last available oxygen in a dying world, dying, at least, in Europe.” On the other hand he states definitely: “I never was a disciple of the surrealist school.” Nor was he. Elytis will have nothing to do with its fundamental poetry, the automatic writing with its unchecked torrent of chance associations. His explorations in poetry’s means of expression lead him to surrealism’s antipodes. Even if its violent display of unproven combinations released his own writing, he is a man of strict form, the master of deliberate creation.

Read his To Axion Estí, by many regarded as his most representative work. With its painstaking composition and stately rhetoric it leaves not one syllable to chance. Or take his love poem Monogram, with its ingenious mathematical basis; it has few counterparts in the literature we know. It comprises seven songs, each with seven lines or multiples of seven in a rising scale 7-2 l-35 up to the middle song’s culmination of 49, where the poem turns round and descends the staircase with exactly the same number of lines, 35-21 – down to the final song’s 7, the starting point. This is nothing that need worry the poem’s readers; it has its beauty without our having to count its steps. But poetry with this structure like an Euclidean linear drawing does not take after surrealism’s écriture automatique.

Elytis’s relationship to the other component, to Greek myth, also calls for clarification. We are used to seeing Greece’s treasure of myths melted down and remoulded to contemporary west-European patterns. We have an Antigone à la Racine, an Antigone à la Anouilh and we shall have more. For Elytis such treatment is odious, a rationalistic pot-cultivation of wildflowers. He himself writes no Antigone à la Breton. He imitates no myths at all and attacks those compatriots who do. In this world of ideas he also has his share of responsibility, though his writing is a repetition not of ancient tales from the Greek past but of the way in which myths are produced.

He sees his Greece with its glorious traditions, its mountains whose peaks with their very names remind us how high the human spirit has attained, and its waters the Aegean Sea, Elytis’s home, whose waves for thousands of years have washed ashore the riches that the West has been able to gather in and pride itself on. For him this Greece is still a living, ever-active myth, and he depicts it just as the old mythmakers did, by personifying it and giving it human form. It lends a sensuous nearness to his visions, and the myth that is the creed of his poetry is incarnated by beautiful young people in an enchanting landscape who love life and each other in dazzling sunshine where the waves break on the shore.

We can call this an optimistic idealization and, despite the concreteness, a flight from the present moment and reality. Elytis’s very language, ritually solemn, is constantly striving to get away from everyday life with its pettiness. The idealization explains both the rapture and the criticism that his poetry has aroused. Elytis himself has given his view of the matter, point by point. Greek as a language, he says, opposes a pessimistic description of life, and for la poésie maudite it has no expressions. For west- Europeans all mysticism is associated with the darkness and the night, but for the Greeks light is the great mystery and every radiant day its recurrent miracle. The sun, the sea and love are the basic and purifying elements.

Those who maintain that all true poetry must be a reflection of its age and a political act he can refer to his harrowing poem about the second lieutenant who fell in the Albanian war. Elytis, himself a second lieutenant, chanced to be one of the two officers who opened the secret order of general mobilization. He took part at the front in the passionate and hopeless fight against Mussolini’s crushing superiority, and his lament over the fallen brother-in-arms, who personifies Greece’s never-completed struggle for existence, is committed poetry in a much more literal and harsher sense than that familiar to those who usually clamour for literature’s commitment.

Elytis’s conclusions from his participation were of a different nature. The poet, he says, does not necessarily have to express his time. He can also heroically defy it. His calling is not to jot down items about our daily life with its social and political situations and private griefs. On the contrary, his only way leads “from what is to what may be”. In its essence, therefore, Elytis’s poetry is not logically clear as we see it but derives its light from the limpidity of the present moment against a perspective behind it. His myth has its roots by the Aegean Sea, which was his cradle, but the myth is about humanity, drawing its nourishment not from a vanished golden age but from one which can never be realized. It is pointless to call this either optimism or pessimism. For, if I have understood him aright, only our future is worth bearing in mind and the unattainable alone is worth striving for.

Cher Maitre,

Malheureusement, mais sans doute au soulagement de l’auditoire, je ne parle pas votre langue. Pour employer la locution anglaise spécifique à quelque chose d’etrange: “It’s Greek to me”. Mais votre poésie n’est certainement pas étrangère, portée par la mer, qui est en même temps la mere de la civilisation européenne. Dans cette descendance nous mettons notre gloire, et, par consequent, il faut que je contredise votre diagnostic de notre état deplorable. Ce dont nous sommes atteints, ce n’est pas du tout d’un excès de rationalisme. Au contraire, la maladie de l’Europe occidentale c’est justement que le rationalisme est rationné. Et le peu que nous en détenons encore, ce ne sont pas les devoirs que nous ont donnés à apprendre nos philosophes de la renaissance. La sagesse claire et la logique pure de Platon et d’Aristote, peut-être aussi de Protagoras, de Gorgias et de Socrate lui-même, voilà les racines du rationalisme, dont nous ne voyons aujourd’hui que les épaves pitoyables.

Néanmoins Socrate, quand la raison ne lui donnait pas de gouverne, a écouté la voix de son daimon, et, cher maître, c’est avec une admiration très profonde que nous avons écouté se faire entendre en votre poésie la même voix de mystère, le daimonde votre pays.

J’ai grand plaisir à vous transmettre les felicitations les plus cordiales de l’Académie suédoise et à vous demander de recevoir des mains de Sa Majesté le Roi le Prix Nobel de litérature de cette année.