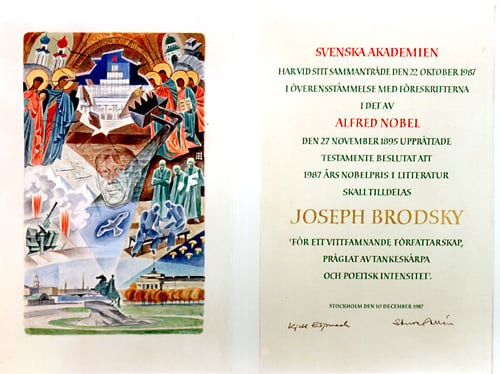

Joseph Brodsky – Nobel diploma

Copyright © The Nobel Foundation 1987

Artist: Gunnar Brusewitz

Calligrapher: Kerstin Anckers

Joseph Brodsky – Banquet speech

Joseph Brodsky’s speech at the Nobel Banquet, December 10, 1987

Your Majesties, Ladies and Gentlemen,

I was born and grew up on the other shore of the Baltic, practically on its opposite grey rustling page. Sometimes on clear days, especially in autumn, standing on a beach somewhere in Kellomaki, a friend would poke his finger north-west across the sheet of water and say: See that blue strip of land? It’s Sweden.

He would be joking, of course: because the angle was wrong, because according to the law of optics, a human eye can travel only for something like twenty miles in open space. The space, however, wasn’t open.

Nonetheless, it pleases me to think, ladies and gentlemen, that we used to inhale the same air, eat the same fish, get soaked by the same – at times – radioactive rain, swim in the same sea, get bored by the same kind of conifers.

Depending on the wind, the clouds I saw from my window were already seen by you, or vice-versa. It pleases me to think that we have had something in common before we ended up in this room.

And as far as this room is concerned, I think it was empty just a couple of hours ago, and it will be empty again a couple of hours hence. Our presence in it, mine especially, is quite incidental from its walls’ point of view. On the whole, from space’s point of view, anyone’s presence is incidental in it, unless one possesses a permanent – and usually inanimate – characteristic of landscape – of a moraine, say, of a hilltop, of a river bend. And it is the appearance of something or somebody unpredictable within a space well used to its contents that creates the sense of occasion.

So being grateful to you for your decision to award me the Nobel Prize for literature, I am essentially grateful for your imparting to my work an aspect of permanence, of a glacier’s debris, let’s say, in the vast landscape of literature.

I am fully aware of the danger hidden in this simile: coldness, uselessness, eventual or fast erosion. Yet if it contains a single vein of animated ore – as I, in my vanity, believe it does – then this simile is perhaps prudent.

As long as I am on the subject of prudence, I should like to add that through recorded history, the audience for poetry seldom amounted to more than 1 % of the entire population. That’s why poets of antiquity or of the Renaissance gravitated to courts, the seats of power; that’s why nowadays they flock to universities, the seats of knowledge. Your academy seems to be a cross between the two; and if in the future – in that time free of ourselves – that 1 % ratio will be sustained, it will be, not to a small degree, due to your efforts. In case this strikes you as a dim vision of the future, I hope that the thought about the population explosion may lift your spirits somewhat. Even a quarter of that 1 % will make a lot of readers, even today.

So my gratitude to you, ladies and gentlemen, is not entirely egoistical. I am grateful to you for those whom your decisions make and will make read poetry, today and tomorrow. I am not so sure that man will prevail, as the great man and my fellow American once said standing, I believe, in this very room; but I am quite positive that a man who reads poetry is harder to prevail upon than upon one who doesn’t.

Of course, it’s one hell of a way to get from Petersburg to Stockholm; but then for a man of my occupation the notion of a straight line being the shortest distance between two points has lost its attraction long time ago. So it pleases me to find out that geography in its own turn is also capable of poetic justice.

Thank you!

Joseph Brodsky – Bibliography

| Works in Russian |

| Stikhotvoreniia i poemy. – Washington, D.C. : Inter-Language Literary Associates, 1965 |

| Ostanovka v pustyne. – New York: Izdatel’stvo imeni Chekhova, 1970. Rev. ed. Ann Arbor, Mich.: Ardis, 1989 |

| Chast’ rechi: Stikhotvoreniia 1972-76. – Ann Arbor, Mich.: Ardis, 1977 |

| Konets prekrasnoi epokhi : stikhotvoreniia 1964-71. – Ann Arbor, Mich.: Ardis, 1977 |

| V Anglii. – Ann Arbor, Mich.: Ardis, 1977 |

| Rimskie elegii. – New York: Russica, 1982 |

| Novye stansy k Avguste : stikhi k M.B., 1962-1982. – Ann Arbor, Mich.: Ardis, 1983 |

| Mramor. – Ann Arbor, Mich.: Ardis, 1984 |

| Uraniia : novaia kniga stikhov. – Ann Arbor, Mich.: Ardis, 1984 |

| Nazidanie : stikhi 1962-1989. – Leningrad : Smart, 1990 |

| Chast’ rechi : Izbrannye stikhi 1962-1989. Moscow: Khudozhestvennaia literatura, 1990 |

| Osennii krik iastreba : Stikhotvoreniia 1962-1989. – Leningrad: KTP LO IMA Press, 1990 |

| Primechaniia paporotnika. – Bromma, Sweden : Hylaea, 1990 |

| Ballada o malen’kom buksire. – Leningrad: Detskaia literatura, 1991 |

| Kholmy : Bol’shie stikhotvoreniia i poemy. – St. Petersburg: LP VTPO “Kinotsentr,” 1991 |

| Stikhotvoreniia. – Tallinn : Eesti Raamat, 1991 |

| Naberezhnaia neistselimykh : Trinadtsat’ essei. – Moscow: Slovo, 1992 |

| Rozhdestvenskie stikhi. – Moscow : Nezavisimaia gazeta, 1992. Rev. – ed. 1996 |

| Sochineniia. – St. Petersburg : Pushkinskii fond, 1992-1995. 4 vol. |

| Vspominaia Akhmatovu / Joseph Brodsky, Solomon Volkov. – Moscow: Nezavisimaia gazeta, 1992 |

| Forma vremeni : stikhotvoreniia, esse, p’esy. – Minsk: Eridan, 1992. 2 vol |

| Kappadokiia. – St. Petersburg, 1993 |

| Persian Arrow/Persidskaia strela / with etchings by Edik Steinberg. – Verona: Edizione d’Arte Gibralfaro & ECM, 1994 |

| Peresechennaia mestnost ‘: Puteshestviia s kommentariiami. – Moscow: Nezavisimaia gazeta, 1995 |

| V okrestnostiakh Atlantidy : Novye stikhotvoreniia. – St. Petersburg: Pushkinskii fond, 1995 |

| Peizazh s navodneniem / compiled by Aleksandr Sumerkin. – Dana Point, Cal.: Ardis, 1996 |

| Brodskii o Tsvetaevoi. – Moscow : Nezavisimaia gazeta, 1997 |

| Pis’mo Goratsiiu. – Moscow: Nash dom, 1998 |

| Sochineniia. – St. Petersburg : Pushkinskii fond. 1998- . 8 vol. |

| Gorbunov i Gorchakov. – St. Petersburg : Pushkinskii fond, 1999 |

| Predstavlenie : novoe literaturnoe obozrenie. – Moscow, 1999 |

| Ostanovka v pustyne. – St. Petersburg : Pushkinskii fond, 2000 |

| Chast’ rechi. – St. Petersburg: Pushkinskii fond, 2000 |

| Konets prekrasnoi epokhi. – St. Petersburg : Pushkinskii fond, 2000 |

| Novye stansy k Avguste. – St. Petersburg : Pushkinskii fond, 2000 |

| Uraniia. – St. Petersburg: Pushkinskii fond, 2000 |

| Peizazh s navodneniem. – St. Petersburg : Pushkinskii fond, 2000 |

| Bol’shaia kniga interv’iu . – Moscow : Zakharov, 2000. |

| Novaia Odisseia : Pamiati Iosifa Brodskogo. – Moscow: Staroe literaturnoe obozrenie, 2001 |

| Peremena imperii : Stikhotvoreniia 1960-1996. – Moscow: Nezavisimaia gazeta, 2001 |

| Vtoroi vek posle nashei ery : dramaturgija Iosifa Brodskogo. – St. Petersburg : Zvezda, 2001 |

| Works in English (including translations into English) |

| Elegy for John Donne and Other Poems / selected, translated, and introduced by Nicholas William Bethell. – London : Longman, 1967 |

| Velka elegie. – Paris : Edice Svedectvi, 1968 |

| Poems. – Ann Arbor, Mich. : Ardis, 1972 |

| Selected Poems / translated from the Russian by George L. Kline. New York: Harper & Row, 1973 |

| Poems and Translations. – Keele: University of Keele, 1977 |

| A Part of Speech. – New York: Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 1980 |

| Verses on the Winter Campaign 1980 / translation by Alan Meyers. – London : Anvil Press, 1981 |

| Less Than One: Selected Essays. – New York: Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 1986 |

| To Urania : Selected Poems, 1965-1985. – New York: Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 1988 |

| Marbles : a Play in Three Acts / translated by Alan Myers with Joseph Brodsky. – New York: Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 1989 |

| Watermark. – New York: Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 1992 |

| On Grief and Reason: Essays. – New York: Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 1995 |

| So Forth : Poems. – New York: Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 1996 |

| Discovery. – New York: Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 1999 |

| Collected Poems in English, 1972-1999 / edited by Ann Kjellberg. – New York: Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 2000 |

| Nativity Poems / translated by Melissa Green … – New York: Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 2001 |

| Critical studies (a selection) |

| Bethea, David M., Joseph Brodsky and the creation of exile . – Princeton, N.J. : Princeton University Press, 1994 |

| Lemkhin, Mikhail, Joseph Brodsky, Leningrad : fragments. – New York : Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1998 |

| MacFadyen, David, Joseph Brodsky and the Baroque. – Liverpool : Liverpool University Press, 1998 |

| Rigsbee, David, Styles of ruin : Joseph Brodsky and the postmodernist elegy. – Westport, Conn. : Greenwood, 1999 |

| Joseph Brodsky : the art of a poem / edited by Lev Loseff and Valentina Polukhina. – Basingstoke : Macmillan, 1999 |

| MacFadyen, David, Joseph Brodsky and the Soviet muse . – Montréal : McGill-Queen, 2000 |

| Joseph Brodsky : conversations / edited by Cynthia L. Haven. – Jackson : University Press of Mississippi, 2003 |

The Swedish Academy, 2006

Joseph Brodsky – Nobel Lecture

English

Russian (pdf)

Nobel Lecture December 8, 1987

(Translation)

I

For someone rather private, for someone who all his life has preferred his private condition to any role of social significance, and who went in this preference rather far – far from his motherland to say the least, for it is better to be a total failure in democracy than a martyr or the crème de la crème in tyranny – for such a person to find himself all of a sudden on this rostrum is a somewhat uncomfortable and trying experience.

This sensation is aggravated not so much by the thought of those who stood here before me as by the memory of those who have been bypassed by this honor, who were not given this chance to address ‘urbi et orbi’, as they say, from this rostrum and whose cumulative silence is sort of searching, to no avail, for release through this speaker.

The only thing that can reconcile one to this sort of situation is the simple realization that – for stylistic reasons, in the first place – one writer cannot speak for another writer, one poet for another poet especially; that had Osip Mandelstam, or Marina Tsvetaeva, or Robert Frost, or Anna Akhmatova, or Wystan Auden stood here, they couldn’t have helped but speak precisely for themselves, and that they, too, might have felt somewhat uncomfortable.

These shades disturb me constantly; they are disturbing me today as well. In any case, they do not spur one to eloquence. In my better moments, I deem myself their sum total, though invariably inferior to any one of them individually. For it is not possible to better them on the page; nor is it possible to better them in actual life. And it is precisely their lives, no matter how tragic or bitter they were, that often move me – more often perhaps than the case should be – to regret the passage of time. If the next life exists – and I can no more deny them the possibility of eternal life than I can forget their existence in this one – if the next world does exist, they will, I hope, forgive me and the quality of what I am about to utter: after all, it is not one’s conduct on the podium which dignity in our profession is measured by.

I have mentioned only five of them, those whose deeds and whose lot matter so much to me, if only because if it were not for them, I, both as a man and a writer, would amount to much less; in any case, I wouldn’t be standing here today. There were more of them, those shades – better still, sources of light: lamps? stars? – more, of course, than just five. And each one of them is capable of rendering me absolutely mute. The number of those is substantial in the life of any conscious man of letters; in my case, it doubles, thanks to the two cultures to which fate has willed me to belong. Matters are not made easier by thoughts about contemporaries and fellow writers in both cultures, poets, and fiction writers whose gifts I rank above my own, and who, had they found themselves on this rostrum, would have come to the point long ago, for surely they have more to tell the world than I do.

I will allow myself, therefore, to make a number of remarks here – disjointed, perhaps stumbling, and perhaps even perplexing in their randomness. However, the amount of time allotted to me to collect my thoughts, as well as my very occupation, will, or may, I hope, shield me, at least partially, against charges of being chaotic. A man of my occupation seldom claims a systematic mode of thinking; at worst, he claims to have a system – but even that, in his case, is borrowing from a milieu, from a social order, or from the pursuit of philosophy at a tender age. Nothing convinces an artist more of the arbitrariness of the means to which he resorts to attain a goal – however permanent it may be – than the creative process itself, the process of composition. Verse really does, in Akhmatova’s words, grow from rubbish; the roots of prose are no more honorable.

II

If art teaches anything (to the artist, in the first place), it is the privateness of the human condition. Being the most ancient as well as the most literal form of private enterprise, it fosters in a man, knowingly or unwittingly, a sense of his uniqueness, of individuality, of separateness – thus turning him from a social animal into an autonomous “I”. Lots of things can be shared: a bed, a piece of bread, convictions, a mistress, but not a poem by, say, Rainer Maria Rilke. A work of art, of literature especially, and a poem in particular, addresses a man tete-a-tete, entering with him into direct – free of any go-betweens – relations.

It is for this reason that art in general, literature especially, and poetry in particular, is not exactly favored by the champions of the common good, masters of the masses, heralds of historical necessity. For there, where art has stepped, where a poem has been read, they discover, in place of the anticipated consent and unanimity, indifference and polyphony; in place of the resolve to act, inattention and fastidiousness. In other words, into the little zeros with which the champions of the common good and the rulers of the masses tend to operate, art introduces a “period, period, comma, and a minus”, transforming each zero into a tiny human, albeit not always pretty, face.

The great Baratynsky, speaking of his Muse, characterized her as possessing an “uncommon visage”. It’s in acquiring this “uncommon visage” that the meaning of human existence seems to lie, since for this uncommonness we are, as it were, prepared genetically. Regardless of whether one is a writer or a reader, one’s task consists first of all in mastering a life that is one’s own, not imposed or prescribed from without, no matter how noble its appearance may be. For each of us is issued but one life, and we know full well how it all ends. It would be regrettable to squander this one chance on someone else’s appearance, someone else’s experience, on a tautology – regrettable all the more because the heralds of historical necessity, at whose urging a man may be prepared to agree to this tautology, will not go to the grave with him or give him so much as a thank-you.

Language and, presumably, literature are things that are more ancient and inevitable, more durable than any form of social organization. The revulsion, irony, or indifference often expressed by literature towards the state is essentially a reaction of the permanent – better yet, the infinite – against the temporary, against the finite. To say the least, as long as the state permits itself to interfere with the affairs of literature, literature has the right to interfere with the affairs of the state. A political system, a form of social organization, as any system in general, is by definition a form of the past tense that aspires to impose itself upon the present (and often on the future as well); and a man whose profession is language is the last one who can afford to forget this. The real danger for a writer is not so much the possibility (and often the certainty) of persecution on the part of the state, as it is the possibility of finding oneself mesmerized by the state’s features, which, whether monstrous or undergoing changes for the better, are always temporary.

The philosophy of the state, its ethics – not to mention its aesthetics – are always “yesterday”. Language and literature are always “today”, and often – particularly in the case where a political system is orthodox – they may even constitute “tomorrow”. One of literature’s merits is precisely that it helps a person to make the time of his existence more specific, to distinguish himself from the crowd of his predecessors as well as his like numbers, to avoid tautology – that is, the fate otherwise known by the honorific term, “victim of history”. What makes art in general, and literature in particular, remarkable, what distinguishes them from life, is precisely that they abhor repetition. In everyday life you can tell the same joke thrice and, thrice getting a laugh, become the life of the party. In art, though, this sort of conduct is called “cliché”.

Art is a recoilless weapon, and its development is determined not by the individuality of the artist, but by the dynamics and the logic of the material itself, by the previous fate of the means that each time demand (or suggest) a qualitatively new aesthetic solution. Possessing its own genealogy, dynamics, logic, and future, art is not synonymous with, but at best parallel to history; and the manner by which it exists is by continually creating a new aesthetic reality. That is why it is often found “ahead of progress”, ahead of history, whose main instrument is – should we not, once more, improve upon Marx – precisely the cliché.

Nowadays, there exists a rather widely held view, postulating that in his work a writer, in particular a poet, should make use of the language of the street, the language of the crowd. For all its democratic appearance, and its palpable advantages for a writer, this assertion is quite absurd and represents an attempt to subordinate art, in this case, literature, to history. It is only if we have resolved that it is time for Homo sapiens to come to a halt in his development that literature should speak the language of the people. Otherwise, it is the people who should speak the language of literature.

On the whole, every new aesthetic reality makes man’s ethical reality more precise. For aesthetics is the mother of ethics; The categories of “good” and “bad” are, first and foremost, aesthetic ones, at least etymologically preceding the categories of “good” and “evil”. If in ethics not “all is permitted”, it is precisely because not “all is permitted” in aesthetics, because the number of colors in the spectrum is limited. The tender babe who cries and rejects the stranger or who, on the contrary, reaches out to him, does so instinctively, making an aesthetic choice, not a moral one.

Aesthetic choice is a highly individual matter, and aesthetic experience is always a private one. Every new aesthetic reality makes one’s experience even more private; and this kind of privacy, assuming at times the guise of literary (or some other) taste, can in itself turn out to be, if not as guarantee, then a form of defense against enslavement. For a man with taste, particularly literary taste, is less susceptible to the refrains and the rhythmical incantations peculiar to any version of political demagogy. The point is not so much that virtue does not constitute a guarantee for producing a masterpiece, as that evil, especially political evil, is always a bad stylist. The more substantial an individual’s aesthetic experience is, the sounder his taste, the sharper his moral focus, the freer – though not necessarily the happier – he is.

It is precisely in this applied, rather than Platonic, sense that we should understand Dostoevsky’s remark that beauty will save the world, or Matthew Arnold’s belief that we shall be saved by poetry. It is probably too late for the world, but for the individual man there always remains a chance. An aesthetic instinct develops in man rather rapidly, for, even without fully realizing who he is and what he actually requires, a person instinctively knows what he doesn’t like and what doesn’t suit him. In an anthropological respect, let me reiterate, a human being is an aesthetic creature before he is an ethical one. Therefore, it is not that art, particularly literature, is a by-product of our species’ development, but just the reverse. If what distinguishes us from other members of the animal kingdom is speech, then literature – and poetry in particular, being the highest form of locution – is, to put it bluntly, the goal of our species.

I am far from suggesting the idea of compulsory training in verse composition; nevertheless, the subdivision of society into intelligentsia and “all the rest” seems to me unacceptable. In moral terms, this situation is comparable to the subdivision of society into the poor and the rich; but if it is still possible to find some purely physical or material grounds for the existence of social inequality, for intellectual inequality these are inconceivable. Equality in this respect, unlike in anything else, has been guaranteed to us by nature. I am speaking not of education, but of the education in speech, the slightest imprecision in which may trigger the intrusion of false choice into one’s life. The existence of literature prefigures existence on literature’s plane of regard – and not only in the moral sense, but lexically as well. If a piece of music still allows a person the possibility of choosing between the passive role of listener and the active one of performer, a work of literature – of the art which is, to use Montale’s phrase, hopelessly semantic – dooms him to the role of performer only.

In this role, it would seem to me, a person should appear more often than in any other. Moreover, it seems to me that, as a result of the population explosion and the attendant, ever-increasing atomization of society (i.e., the ever-increasing isolation of the individual), this role becomes more and more inevitable for a person. I don’t suppose that I know more about life than anyone of my age, but it seems to me that, in the capacity of an interlocutor, a book is more reliable than a friend or a beloved. A novel or a poem is not a monologue, but the conversation of a writer with a reader, a conversation, I repeat, that is very private, excluding all others – if you will, mutually misanthropic. And in the moment of this conversation a writer is equal to a reader, as well as the other way around, regardless of whether the writer is a great one or not. This equality is the equality of consciousness. It remains with a person for the rest of his life in the form of memory, foggy or distinct; and, sooner or later, appropriately or not, it conditions a person’s conduct. It’s precisely this that I have in mind in speaking of the role of the performer, all the more natural for one because a novel or a poem is the product of mutual loneliness – of a writer or a reader.

In the history of our species, in the history of Homo sapiens, the book is anthropological development, similar essentially to the invention of the wheel. Having emerged in order to give us some idea not so much of our origins as of what that sapiens is capable of, a book constitutes a means of transportation through the space of experience, at the speed of a turning page. This movement, like every movement, becomes a flight from the common denominator, from an attempt to elevate this denominator’s line, previously never reaching higher than the groin, to our heart, to our consciousness, to our imagination. This flight is the flight in the direction of “uncommon visage”, in the direction of the numerator, in the direction of autonomy, in the direction of privacy. Regardless of whose image we are created in, there are already five billion of us, and for a human being there is no other future save that outlined by art. Otherwise, what lies ahead is the past – the political one, first of all, with all its mass police entertainments.

In any event, the condition of society in which art in general, and literature in particular, are the property or prerogative of a minority appears to me unhealthy and dangerous. I am not appealing for the replacement of the state with a library, although this thought has visited me frequently; but there is no doubt in my mind that, had we been choosing our leaders on the basis of their reading experience and not their political programs, there would be much less grief on earth. It seems to me that a potential master of our fates should be asked, first of all, not about how he imagines the course of his foreign policy, but about his attitude toward Stendhal, Dickens, Dostoevsky. If only because the lock and stock of literature is indeed human diversity and perversity, it turns out to be a reliable antidote for any attempt – whether familiar or yet to be invented – toward a total mass solution to the problems of human existence. As a form of moral insurance, at least, literature is much more dependable than a system of beliefs or a philosophical doctrine.

Since there are no laws that can protect us from ourselves, no criminal code is capable of preventing a true crime against literature; though we can condemn the material suppression of literature – the persecution of writers, acts of censorship, the burning of books – we are powerless when it comes to its worst violation: that of not reading the books. For that crime, a person pays with his whole life; if the offender is a nation, it pays with its history. Living in the country I live in, I would be the first prepared to believe that there is a set dependency between a person’s material well-being and his literary ignorance. What keeps me from doing so is the history of that country in which I was born and grew up. For, reduced to a cause-and-effect minimum, to a crude formula, the Russian tragedy is precisely the tragedy of a society in which literature turned out to be the prerogative of the minority: of the celebrated Russian intelligentsia.

I have no wish to enlarge upon the subject, no wish to darken this evening with thoughts of the tens of millions of human lives destroyed by other millions, since what occurred in Russia in the first half of the Twentieth Century occurred before the introduction of automatic weapons – in the name of the triumph of a political doctrine whose unsoundness is already manifested in the fact that it requires human sacrifice for its realization. I’ll just say that I believe – not empirically, alas, but only theoretically – that, for someone who has read a lot of Dickens, to shoot his like in the name of some idea is more problematic than for someone who has read no Dickens. And I am speaking precisely about reading Dickens, Sterne, Stendhal, Dostoevsky, Flaubert, Balzac, Melville, Proust, Musil, and so forth; that is, about literature, not literacy or education. A literate, educated person, to be sure, is fully capable, after reading this or that political treatise or tract, of killing his like, and even of experiencing, in so doing, a rapture of conviction. Lenin was literate, Stalin was literate, so was Hitler; as for Mao Zedong, he even wrote verse. What all these men had in common, though, was that their hit list was longer than their reading list.

However, before I move on to poetry, I would like to add that it would make sense to regard the Russian experience as a warning, if for no other reason than that the social structure of the West up to now is, on the whole, analogous to what existed in Russia prior to 1917. (This, by the way, is what explains the popularity in the West of the Nineteenth-Century Russian psychological novel, and the relative lack of success of contemporary Russian prose. The social relations that emerged in Russia in the Twentieth Century presumably seem no less exotic to the reader than do the names of the characters, which prevent him from identifying with them.) For example, the number of political parties, on the eve of the October coup in 1917, was no fewer than what we find today in the United States or Britain. In other words, a dispassionate observer might remark that in a certain sense the Nineteenth Century is still going on in the West, while in Russia it came to an end; and if I say it ended in tragedy, this is, in the first place, because of the size of the human toll taken in course of that social – or chronological – change. For in a real tragedy, it is not the hero who perishes; it is the chorus.

IlI

Although for a man whose mother tongue is Russian to speak about political evil is as natural as digestion, I would here like to change the subject. What’s wrong with discourses about the obvious is that they corrupt consciousness with their easiness, with the quickness with which they provide one with moral comfort, with the sensation of being right. Herein lies their temptation, similar in its nature to the temptation of a social reformer who begets this evil. The realization, or rather the comprehension, of this temptation, and rejection of it, are perhaps responsible to a certain extent for the destinies of many of my contemporaries, responsible for the literature that emerged from under their pens. It, that literature, was neither a flight from history nor a muffling of memory, as it may seem from the outside. “How can one write music after Auschwitz?” inquired Adorno; and one familiar with Russian history can repeat the same question by merely changing the name of the camp – and repeat it perhaps with even greater justification, since the number of people who perished in Stalin’s camps far surpasses the number of German prisoncamp victims. “And how can you eat lunch?” the American poet Mark Strand once retorted. In any case, the generation to which I belong has proven capable of writing that music.

That generation – the generation born precisely at the time when the Auschwitz crematoria were working full blast, when Stalin was at the zenith of his Godlike, absolute power, which seemed sponsored by Mother Nature herself – that generation came into the world, it appears, in order to continue what, theoretically, was supposed to be interrupted in those crematoria and in the anonymous common graves of Stalin’s archipelago. The fact that not everything got interrupted, at least not in Russia, can be credited in no small degree to my generation, and I am no less proud of belonging to it than I am of standing here today. And the fact that I am standing here is a recognition of the services that generation has rendered to culture; recalling a phrase from Mandelstam, I would add, to world culture. Looking back, I can say again that we were beginning in an empty – indeed, a terrifyingly wasted – place, and that, intuitively rather than consciously, we aspired precisely to the recreation of the effect of culture’s continuity, to the reconstruction of its forms and tropes, toward filling its few surviving, and often totally compromised, forms, with our own new, or appearing to us as new, contemporary content.

There existed, presumably, another path: the path of further deformation, the poetics of ruins and debris, of minimalism, of choked breath. If we rejected it, it was not at all because we thought that it was the path of self-dramatization, or because we were extremely animated by the idea of preserving the hereditary nobility of the forms of culture we knew, the forms that were equivalent, in our consciousness, to forms of human dignity. We rejected it because in reality the choice wasn’t ours, but, in fact, culture’s own – and this choice, again, was aesthetic rather than moral.

To be sure, it is natural for a person to perceive himself not as an instrument of culture, but, on the contrary, as its creator and custodian. But if today I assert the opposite, it’s not because toward the close of the Twentieth Century there is a certain charm in paraphrasing Plotinus, Lord Shaftesbury, Schelling, or Novalis, but because, unlike anyone else, a poet always knows that what in the vernacular is called the voice of the Muse is, in reality, the dictate of the language; that it’s not that the language happens to be his instrument, but that he is language’s means toward the continuation of its existence. Language, however, even if one imagines it as a certain animate creature (which would only be just), is not capable of ethical choice.

A person sets out to write a poem for a variety of reasons: to win the heart of his beloved; to express his attitude toward the reality surrounding him, be it a landscape or a state; to capture his state of mind at a given instant; to leave – as he thinks at that moment – a trace on the earth. He resorts to this form – the poem – most likely for unconsciously mimetic reasons: the black vertical clot of words on the white sheet of paper presumably reminds him of his own situation in the world, of the balance between space and his body. But regardless of the reasons for which he takes up the pen, and regardless of the effect produced by what emerges from beneath that pen on his audience – however great or small it may be – the immediate consequence of this enterprise is the sensation of coming into direct contact with language or, more precisely, the sensation of immediately falling into dependence on it, on everything that has already been uttered, written, and accomplished in it.

This dependence is absolute, despotic; but it unshackles as well. For, while always older than the writer, language still possesses the colossal centrifugal energy imparted to it by its temporal potential – that is, by all time Iying ahead. And this potential is determined not so much by the quantitative body of the nation that speaks it (though it is determined by that, too), as by the quality of the poem written in it. It will suffice to recall the authors of Greek or Roman antiquity; it will suffice to recall Dante. And that which is being created today in Russian or English, for example, secures the existence of these languages over the course of the next millennium also. The poet, I wish to repeat, is language’s means for existence – or, as my beloved Auden said, he is the one by whom it lives. I who write these lines will cease to be; so will you who read them. But the language in which they are written and in which you read them will remain not merely because language is more lasting than man, but because it is more capable of mutation.

One who writes a poem, however, writes it not because he courts fame with posterity, although often he hopes that a poem will outlive him, at least briefly. One who writes a poem writes it because the language prompts, or simply dictates, the next line. Beginning a poem, the poet as a rule doesn’t know the way it’s going to come out, and at times he is very surprised by the way it turns out, since often it turns out better than he expected, often his thought carries further than he reckoned. And that is the moment when the future of language invades its present.

There are, as we know, three modes of cognition: analytical, intuitive, and the mode that was known to the Biblical prophets, revelation. What distinguishes poetry from other forms of literature is that it uses all three of them at once (gravitating primarily toward the second and the third). For all three of them are given in the language; and there are times when, by means of a single word, a single rhyme, the writer of a poem manages to find himself where no one has ever been before him, further, perhaps, than he himself would have wished for. The one who writes a poem writes it above all because verse writing is an extraordinary accelerator of conscience, of thinking, of comprehending the universe. Having experienced this acceleration once, one is no longer capable of abandoning the chance to repeat this experience; one falls into dependency on this process, the way others fall into dependency on drugs or on alcohol. One who finds himself in this sort of dependency on language is, I guess, what they call a poet.

Translated from the Russian by Barry Rubin.

Joseph Brodsky – Other resources

Links to other sites

On Joseph Brodsky from Pegasos Author’s Calendar

On Joseph Brodsky from The Academy of American Poets

Joseph Brodsky – Poetry

English

Seven Strophes

I was but what you’d brush

with your palm, what your leaning

brow would hunch to in evening’s

raven-black hush.

I was but what your gaze

in that dark could distinguish:

a dim shape to begin with,

later – features, a face.

It was you, on my right,

on my left, with your heated

sighs, who molded my helix,

whispering at my side.

It was you by that black

window’s trembling tulle pattern

who laid in my raw cavern

a voice calling you back.

I was practically blind.

You, appearing, then hiding,

gave me my sight and heightened

it. Thus some leave behind

a trace. Thus they make worlds.

Thus, having done so, at random

wastefully they abandon

their work to its whirls.

Thus, prey to speeds

of light, heat, cold, or darkness,

a sphere in space without markers

spins and spins.

“Seven Strophes” from COLLECTED POEMS IN ENGLISH

by Joseph Brodsky.

Copyright © 2000 by the Estate of Joseph Brodsky.

Used by permission of Farrar, Straus and Giroux, LLC.

All rights reserved.

CAUTION: Users are warned that this work is

protected under copyright laws and downloading is strictly prohibited. The right to reproduce or transfer the work via any medium must be secured with Farrar, Straus and Giroux, LLC.

Poem selected by the Nobel Library of the Swedish Academy.

Joseph Brodsky – Prose

English

Excerpt from Watermark

I always adhered to the idea that God is time, or at least that His spirit is. Perhaps this idea was even of my own manufacture, but now I don’t remember. In any case, I always thought that if the Spirit of God moved upon the face of the water, the water was bound to reflect it. Hence my sentiment for water, for its folds, wrinkles, and ripples, and – as I am a Northerner – for its grayness. I simply think that water is the image of time, and every New Year’s Eve, in somewhat pagan fashion, I try to find myself near water, preferably near a sea or an ocean, to watch the emergence of a new helping, a new cupful of time from it. I am not looking for a naked maiden riding on a shell; I am looking for either a cloud or the crest of a wave hitting the shore at midnight. That, to me, is time coming out of water, and I stare at the lace-like pattern it puts on the shore, not with a gypsy-like knowing, but with tenderness and with gratitude.

This is the way, and in my case the why, I set my eyes on this city. There is nothing Freudian to this fantasy, or specifically chordate, although some evolutionary – if not plainly atavistic – or autobiographical connection could no doubt be established between the pattern a wave leaves upon the sand and its scrutiny by a descendant of the ichthyosaur, and a monster himself. The upright lace of Venetian façades is the best line time-alias-water has left on terra firma anywhere. Plus, there is no doubt a correspondence between – if not an outright dependence on – the rectangular nature of that lace’s displays – i.e., local buildings – and the anarchy of water that spurns the notion of shape. It is as though space, cognizant here more than anyplace else of its inferiority to time, answers it with the only property time doesn’t possess: with beauty. And that’s why water takes this answer, twists it, wallops and shreds it, but ultimately carries it by and large intact off into the Adriatic.

The eye in this city acquires an autonomy similar to that of a tear. The only difference is that it doesn’t sever itself from the body but subordinates it totally. After a while – on the third or fourth day here – the body starts to regard itself as merely the eye’s carrier, as a kind of submarine to its now dilating, now squinting periscope. Of course, for all its targets, its explosions are invariably self-inflicted: it’s your own heart, or else your mind, that sinks; the eye pops up to the surface. This of course owes to the local topography, to the streets – narrow, meandering like eels – that finally bring you to a flounder of a campo with a cathedral in the middle of it, barnacled with saints and flaunting its Medusa-like cupolas. No matter what you set out for as you leave the house here, you are bound to get lost in these long, coiling lanes and passageways that beguile you to see them through, to follow them to their elusive end, which usually hits water, so that you can’t even call it a cul-de-sac. On the map this city looks like two grilled fish sharing a plate, or perhaps like two nearly overlapping lobster claws (Pasternak compared it to a swollen croissant); but it has no north, south, east, or west; the only direction it has is sideways. It surrounds you like frozen seaweed, and the more you dart and dash about trying to get your bearings, the more you get lost. The yellow arrow signs at intersections are not much help either, for they, too, curve. In fact, they don’t so much help you as kelp you. And in the fluently flapping hand of the native whom you stop to ask for directions, the eye, oblivious to his sputtering A destra, a sinistra, dritto, dritto, readily discerns a fish.

Excerpt from WATERMARK by Joseph Brodsky.

Copyright © 1992 by Joseph Brodsky.

Reprinted by permission of Farrar, Straus and Giroux, LLC.

CAUTION: Users are warned that this work is protected under copyright laws and downloading is strictly prohibited. The right to reproduce or transfer the work via any medium must be secured with Farrar, Straus and Giroux, LLC.

Excerpt selected by the Nobel Library of the Swedish Academy.

Joseph Brodsky – Prose

Swedish

Utdrag ur Vattenspegel

Jag har alltid varit anhängare av tanken att Gud är tid, eller åtminstone att Hans Ande är det. Kanske är tanken till och med av eget fabrikat, men det minns jag inte nu. Hur som helst har jag alltid tänkt att om Guds Ande rört sig över vattenytan, måste vattnet med nödvändighet reflektera den. Härav min känsla för vattnet, för dess veck, skrynklor och krusningar och – eftersom jag är nordbo – för dess gråhet. Jag tror helt enkelt att vattnet är tidens avbild, och varje nyårsafton försöker jag, på ett något hedniskt vis, se till att jag befinner mig i närheten av vatten, helst vid ett hav eller en ocean, för att se en ny mängd, ett nytt mått tid skölja upp ur det. Jag spanar inte efter en naken jungfru ridande på ett snäckskal; jag spanar antingen efter ett moln eller efter kammen på en våg som slår mot stranden vid midnatt. Detta är, för mig, tid som kommer ur vatten, och jag stirrar på spetsmönstret som det lämnar på stranden inte med zigenarlik kunskap utan med ömhet och tacksamhet.

Det är av denna anledning som jag kastade mina blickar på den här stan. Denna fantasi har inget med Freud eller med ryggsträngsdjur att göra, även om man säkert skulle kunna upprätta något slags evolutionärt – om inte rent atavistiskt – eller självbiografiskt samband mellan det mönster en våg lämnar på sanden och det studium av det som en ättling till fisködlan, själv ett monster, ägnar sig åt. De venetianska fasadernas lodräta spetsverk är den bästa linje som tiden-alias-vattnet lämnat någonstans på terra firma. Plus att det säkert finns en överensstämmelse – om än inte ett direkt samband – mellan det där spetsverkets rektangulära uttryck – dvs. stadens byggnader – och anarkin hos vattnet, som avvisar alla föreställningar om form. Det är som om rummet, här mer än någon annanstans medvetet om sin underlägsenhet gentemot tiden, ger svar på tal med den enda egenskap som tiden saknar: skönhet. Och det är därför som vattnet tar det här svaret, förvränger det, bultar om det och strimlar det men till slut släpper ut det i stort sett intakt i Adriatiska havet.

I den här stan uppnår ögat en självständighet som påminner om tårens. Den enda skillnaden är att ögat inte lösgör sig från kroppen utan helt underordnar den sig. Efter ett tag – på tredje eller fjärde dan här – börjar kroppen betrakta sig enbart som en bärare åt ögat, som ett slags undervattensbåt med ett än vidöppet, än kisande periskop. Men trots alla måltavlor är det man själv som drabbas av explosionerna: det är ens egen själ eller hjärta som sjunker; ögat stiger upp till ytan. Detta har naturligtvis med platsens topografi att göra, med gatorna – smala, slingrande som ålar – som till slut leder fram en till flundran av en campo med en katedral i mitten, krönt av helgon och prålande med medusaliknande kupoler. Vilka planer man än hade när man lämnade huset, kommer man att gå vilse i dessa långa ringlande gränder och prång som man lockas att genomkorsa och följa till deras gäckande slut – som för det mesta innebär vatten, vilket gör att de inte ens kan kallas återvändsgränder. På kartan ser stan ut som två halstrade fiskar som delar en tallrik, eller kanske som två hummerklor som nästan överlappar varandra (Pasternak jämförde den med en uppsvälld giffel); men den har varken norr, syd, öst eller väst; den enda riktning den har är: åt sidan. Den omsluter en som fruset sjögräs, och ju mer man kastar och slår för att hitta sin bäring, desto mer går man bort sig. De gula skyltarna vid gatukorsningarna är inte heller till stor hjälp, för de kröker sig de med. Man är tångens fånge. Och när man hejdar en ortsbo för att fråga om vägen, urskiljer ögat, glömsk av hans smattrande a destra, a sinistra, dritto, dritto, i den följsamt flaxande handen utan svårighet en fisk.

Utdrag ur Vattenspegel. En bok om Venedig

Amerikansk originaltitel: Watermark

Översättning från engelskan av Bengt Jangfeldt

© Joseph Brodsky 1992

© Svensk översättning Wahlström & Widstrand 1992

ISBN 91-46-16198-8

Utdraget valt av Nobelbiblioteket, Svenska Akademien.

Joseph Brodsky – Poetry

Swedish

Sju strofer och dagar

Jag var bara det, som du

berörde med handen,

över vilket du lutade pannan

i nattens korpsvarta djup.

Jag var bara det, som du vagt

kunde skönja där nere;

först oklarheten inkarnerad,

långt senare – ansiktsdrag.

Det var du som, het,

i mitt vänstra och mitt högra öra

skapade musslan för att höra,

viskande i det.

Det var du, där du stod

och fingrade på gardinen,

som i den råa munhålan lade in den

röst, som sen följt dig med rop.

Jag var blind, helt enkelt. Men då

dök du upp, för att sedan fly mig,

och skänkte mig därmed synen.

Det är så man lämnar spår.

Det är så som världar blir till.

Så slösas gåvor, ty för det mesta

lämnas världarna sedan att kretsa

och klara sig bäst de vill.

Så snurrar på sin färd,

förlorad i världsalltets töcken,

slungad mellan ljus och mörker,

hetta och kyla, en sfär.

“Sju strofer och dagar” ur Ett liv i spritt ljus

Översättning av Bengt Jangfeldt

© Joseph Brodsky 1989

© Svensk översättning Wahlström & Widstrand 1989

ISBN 91-46-15740-9

Dikten vald av Nobelbiblioteket, Svenska Akademien.

Joseph Brodsky: A Virgilian Hero, Doomed Never to Return Home

Joseph Brodsky: A Virgilian Hero, Doomed Never to Return Home

by Bengt Jangfeldt*

This article was published on 12 December 2003.

“All my poems are more or less about the same thing – about Time. About what time does to Man.” – Joseph Brodsky

Rebel Poet

It is impossible to speak about Russian literature without taking into account the society in which it was written. This is especially true for the 20th century, when five Russian writers were awarded the Nobel Prize. When the émigré writer Ivan Bunin got it in 1933, the Swedish Academy was reproached for not having awarded the prize to the pro-Soviet Maxim Gorki; Boris Pasternak‘s prize, in 1958, was fiercely attacked by the Soviet authorities as a political, anti-Soviet act; Mikhail Sholokhov‘s, seven years later, was criticized for being, in its turn, a conciliatory gesture toward the Soviet regime; and Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn‘s award (1970) was conceived in the same vein as the prize to Pasternak.

Iosif Brodskiy photographed by his father, Alexandr Brodskiy, on the balcony of their apartment in Leningrad in 1958.

Photo: Courtesy of Mikhail Miltchik, St. Petersburg

When Joseph Brodsky was awarded the Nobel Prize in 1987, times were changing. The Soviet Union was opening up, but the authorities were still not able to cope with the fact that a Russian writer had got the prize, and it was announced with great delay.

Iosif Brodskiy was born in Leningrad in 1940 and died in New York in 1996 as Joseph Brodsky. Between the two spellings of his name lies one of the more dramatic human and poetic destinies in 20th century Russia – a country rich in drama.

Iosif Brodskiy grew up in the Soviet Union, first during the Stalinist era, then under the milder political climate of Khrushchev and Brezhnev. He started to write poetry at the end of the 1950s, but like everybody else who refused to accept the Soviet aesthetic norms he encountered great difficulties and could only publish a few poems.

Brodskiy revolutionised Russian poetry by introducing themes that were taboo in the Soviet Union, first of all metaphysical and Biblical ones. And he did it in a verse that was both innovative and exceptionally varied. Influenced by his Russian 18th century precursors (first of all Derzhavin), as well as by Polish poets (Galczynski, Norwid) and the English Metaphysicals (Donne, Herbert, Marvell), Brodskiy enriched Russian literature with a new ironic sensibility. The conspicuous use of literary reminiscences and allusions could perhaps be seen as a result of his growing up in almost total cultural isolation, where every alternative voice was eagerly absorbed.

In the Soviet Union such things did not go unpunished. The young poet was regarded as a rebel and a parasite: he was arrested and, after a parody of a trial, in 1964 exiled to northern Russia to think better of it. This he did, but not in the way the authorities had wished. During his exile he developed his poetic technique and ripened as a poet. And thanks to protests from Soviet and Western intellectuals, he was set free in 1965, before the end of his term. He returned to his hometown, Leningrad, where he stayed until he was sent into foreign exile in 1972 – this time without trial and for good. He settled in the USA, where he became Joseph Brodsky, an American citizen, and where he lived until his death twenty-four years later.

|

| Brodskiy during his exile in Northern Russia. Photo: Alexandr Brodskiy Courtesy of Mikhail Miltchik, St. Petersburg |

In the USA, Brodsky continued to write poetry in Russian, and also translated many of his poems into English. If he never reached the same poetic peaks in English as in Russian, he developed instead into a brilliant essayist in English. As a writer Brodsky thus had two identities, and it was in his capacity as one of the greatest Russian poets of the 20th century and a major essayist in the English language that he was acclaimed by the Swedish Academy in 1987 for his “all-embracing authorship, imbued with clarity of thought and poetic intensity”.

Time Is Greater than Space

His first collection of essays, Less Than One, was published in 1986. Some of the best essays were devoted to his great predecessors in Russian poetry – Osip Mandelstam, Anna Akhmatova, and Marina Tsvetayeva. In an essay on Tsvetayeva, Brodsky formulates his view of the poet as a “combination of an instrument and a human being in one person, with the former gradually taking over the latter”.

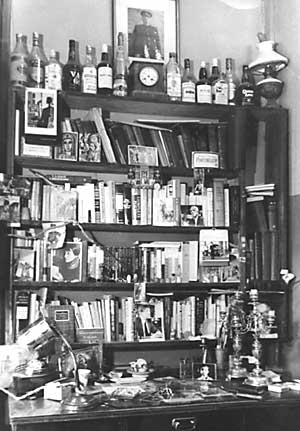

Brodskiy’s study photographed on June 4, 1972, the same day he was exiled from the Soviet Union.

Photo: Courtesy of Mikhail Miltchik

The poet, transformed gradually into an instrument for his poetic gift, has no choice – and the recognition of this exclusiveness determines his path. By constantly listening to his own voice, constantly developing his language, constantly taking the next stylistic step, he becomes more and more isolated.

Brodsky’s words about Tsvetayeva are a self-characterisation. Brodsky the poet is led farther and farther away from the literary mainstream by language itself. And Brodsky the man, grown up in a society with whose values he cannot reconcile himself and which refuses to accept him, is, like Tsvetayeva and Mandelstam, forced into a growing social alienation. The exile to northern Russia and his expatriation eight years later are but outer confirmations of an inner process that in other countries would have taken less dramatic turns.

In the poem “Lullaby of Cape Cod” (1975), Brodsky describes his “move” to the USA as a “change of Empire”. However shattering this experience may be, it changes nothing in essence. Empires have always existed and resemble one another, if not in detail (one empire can, of course, be more repugnant than the other), then at least in structure – and as regards man’s place in this structure. Although Brodsky was heavily marked by his Soviet experience, he had no illusions about other political systems being able to provide a perfect alternative. The big enemy is not space but time.

It is Brodsky’s approach to time that determines his worldview. “What interests me and always has interested me most is time and its effect on man, how it changes him, grinds him… On the other hand, this is just a metaphor for what time does to space and the world.” Time reigns supreme – all that is not time is subjected to the power of time, “the ruler”, “the owner”. Time is the enemy of man and everything man has created and holds dear: “Ruins are the triumph of oxygen and time.”

Time clings to man, who grows older, dies and turns into “dust” – “time’s flesh”, as Brodsky calls it. Key words in his poetry are “splinter”, “shard”, “fragment”. One of his books of poetry is called A Part of Speech. Man – in particular, a poet – is a part of a language that is older than he and will live on after time has settled the account with language’s servant.

Man is attacked both by the past and the future. What we experience as unpleasant and negative in life is, as a matter of fact, a cry from the future, which is trying to break ground in the present. The only thing that prevents the future and the past from merging is the short period constituted by the present, symbolised by man and his body in “Ecloque IV: Winter” (1977):

… What sets them apart is only

a warm body. Mule-like, stubborn creature,

it stands firmly between them, rather

like a border guard: stiffened, sternly

preventing the wandering of the futureinto the past. …

On the personal level, Brodsky views life as a “one way street”. A return to what has passed – an earlier life, a woman – is impossible. In “December in Florence” (1976), about Dante and his hometown, about the poet and exile, Florence is double-exposed with another city – Leningrad. There are, writes Brodsky,

… cities one won’t see again. The sun

throws its gold at their frozen windows. But all the same

there is no entry, no proper sum.

There are always six bridges spanning the sluggish river.

There are places where lips touched lips for the first time ever,

or pen pressed paper with real fervor.

There are arcades, colonnades, iron idols that blur your lens.

There the streetcar’s multitudes, jostling, dense,

speak in the tongue of a man who’s departed thence.

In spite of all Communism, “Leningrad”, that is, St. Petersburg, remains “the most beautiful city in the world”. The return is not impossible primarily because of an unpalatable political system – which a superficial reading might suggest – but by deeper, psychological factors: “A man moves only in one direction. And only from. From a place, from a thought that has entered his mind, from himself… that is, constantly away from what has been experienced…”

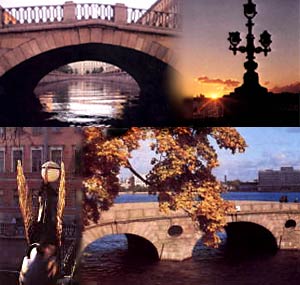

|

| Bridges in St. Petersburg (clockwise): Troitsky Bridge, Prachechny Bridge, Bankovsky Bridge, Kamenny Bridge. Photos: Courtesy of Greg Ofman |

The individual’s journey in time and space is matched by a similar development toward non-existence on the historic plane. Not so much because of the threat of atomic bombs or other acts of war but because societies and civilisations are subject to the same “time war” as the individual. To Brodsky, the big threat comes from the demographic changes leading to the peril of Western, that is, individual-based, civilisation. A recurring theme is the diminishing role of the Christian world – to Brodsky, as to Osip Mandelstam, “Christianity” is first and foremost a question of civilisation – in favour of the “anti-individualistic pathos of an overpopulated world”. Thus the individual’s future merges with the world’s: the death of the individual with that of individualism.

Language Is Greater than Time

Against all-devouring Time, which leads to the absence of both the individual and the world, Brodsky mobilises the word. Few modern poets have stressed with such intensity the word’s ability to withstand the passing of time. This conviction recurs frequently in Brodsky’s poems, often in the last lines:

I don’t know anymore what earth will nurse my carcass.

Scratch on, my pen: let’s mark the white the way it marks us.

(“The Fifth Anniversary”, 1977)

That’s the birth of an eclogue. Instead of the shepherd’s signal,

A lamp’s flaring up. Cyrillic, while running witless

on the pad as though to escape the captor,

knows more of the future than the famous sibyl:

of how to darken against the whiteness,

as long as the whiteness lasts. And after.

(“Eclogue IV: Winter”)

Brodsky’s belief in the power of the word must be seen against his view of time and space. Literature is superior to society – and to the writer himself. The idea that it is not the language but the poet who is the instrument is, as we have seen, at the core of Brodsky’s poetics. Language is older than society and, naturally, older than the poet, and it is language that keeps nations together when “the centre cannot hold” (with Yeats‘s words).

Joseph Brodsky (left) and fellow Nobel Prize Laureate Derek Walcott in the park of Alfred Nobel’s home at Björkborn, Sweden, 1993.

Photo: Bengt Jangfeldt

Men die, writers do not. A poet who formulated the same thought with similar pregnancy was W.H. Auden in his “In Memory of W.B. Yeats” (1939). It was the third and last part of this triptych that made such an indelible impression on Brodsky (he describes it in the essay “Less Than One”) when he first read the poem during his exile in northern Russia:

Time that is intolerant

Of the brave and innocent,

And indifferent in a week

To a beautiful physique,Worships language and forgives

Everyone by whom it lives …

Language, in other words, is superior not only to society and the poet but to time itself. Time “worships language” and is thus “lesser” than it. There is a strain of a romantic fatalism in this assertion, but in Russia, a country where people, in Pushkin’s words, are always “mute”, the writer has always occupied a unique position. This emphasis on the dominance of language is thus not an expression of aestheticism; in a society where language is nationalised, where language is political even when it does not speak of politics, the word possesses an enormous explosive force.

Poetry Is Greater than Prose

In Brodsky’s aesthetical hierarchy, poetry occupies the first place. “The concept of equality is extrinsic to the nature of art, and the thinking of any man of letters is hierarchical. Within this hierarchy, poetry occupies a higher position than prose…” This does not mean that poetry is “better” than prose but is a logical conclusion of Brodsky’s view of the hierarchy Language-Time-Space. Time is greater than space, but language is greater than time. To write is essentially to try to “regain” or “hold back” time, and for this purpose the poet has at his disposal means that the prose-writer lacks: meter and caesuras, syntactic pauses, stressed and unstressed syllables. An important means of restructuring and holding back time is rhyme, which refers back but also creates expectation, that is, future. “Song is, after all, restructured time”, says Brodsky (in his essay on Osip Mandelstam), or simply, speaking of Auden, “a repository of time”. And if language lives by the poet, does then not “time” live by the poet, in his poems?

In order best to move with time, the poem should try to imitate time’s monotone, try to make it resemble the sound produced by a pendulum. Brodsky’s own voice is described as almost inaudible:

I am speaking to you, and it’s not my fault

if you don’t hear. The sum of days, by slugging

on, blisters eyeballs; the same goes for vocal cords.

My voice may be muffled but, I should hope, not nagging.All the better to hear the crowing of a cockerel, the tick-tocks

in the heart of a record, its needle’s patter;

all the better for you not to notice when my talk stops,

as Little Red Riding Hood didn’t mutter to her gray partner.

(“Afterword”, 1986)

The poet’s voice, “more muffled than the bird’s, but more sonorous than the pike’s”, as it is characterised in the poem “Comments from a Fern” (1989), is so subdued that it almost erases the difference between sound and silence, and so close to time’s rhythm one can get – a rhythm that the poet can approximate with the help of meter. When Brodsky stresses the importance of classical forms, he is not just being conservative; he does it with a belief in their double function as a structuring element and upholder of civilisation; the assertion of the absolute value of these stylistic means are thus not primarily a question of form but an important part of what could be called Brodsky’s philosophy of culture.

Linear Thinking

Joseph Brodsky wrote poetry for the better part of his life, and the history of his publications is a reflection of the political system he grew up in. His first books were selections from his poetry published by friends and admirers in the West and were forbidden reading in his home country. In the Soviet Union, his first book was published only after the Nobel Prize. A full-scale publication of his works, including Russian translations of his essays, was made possible only after the fall of the Communist dictatorship in 1991.

|

| Brodsky with his cat Mississippi, New York, November 1987. Photo: Bengt Jangfeldt |

One consequence of Brodsky’s idea that a person moves only in one direction – from – was that he never went back to his homeland. His thinking – and acting – was linear. From the age of thirty-two he was a “nomad” – a Virgilian hero, doomed never to return home.

When asked why he did not want to go back, Brodsky answered that he didn’t want to visit his home country as a tourist. Or that he didn’t want to go on an invitation from official institutions. His final argument was: “The best part of me is already there: my poetry.”

* Bengt Jangfeldt has been specializing in Russian literature for 30 years. His doctoral thesis (1976) treated the relationship between the Soviet State and the literary avant-garde during the years of the revolution, 1917-1921. This work was later supplemented by a series of archival editions.

Professor Jangfeldt has collected and published the correspondence between Vladimir Mayakovsky and Lili Brik (in Russian in 1982 and 1991, in English in 1986: “Love is the Heart of Everything”) as well as the literary legacy of the great Russian linguist, Roman Jakobson (Russian edition 1992, English edition 1997: “My Futurist Years”). During the last ten years he has been focusing on the historical ties between Sweden and the St. Petersburg region. This work has resulted in several books, including Svenska vägar till S:t Petersburg which in 1998 was awarded the August Prize (the Swedish equivalent of the Booker Prize). His last books include an authorised biography of the Swedish author and doctor Axel Munthe (En osalig ande, 2003).

Bengt Jangfeldt has translated many of Joseph Brodsky’s works into Swedish, the poetry from Russian and the prose from English. In 1988, he was awarded the Letterstedt Prize for Translation by the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences for rendering into Swedish Brodsky’s book of essays, “Less Than One”.

First published 12 December 2003