LINDA B. BUCK

Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine 2004

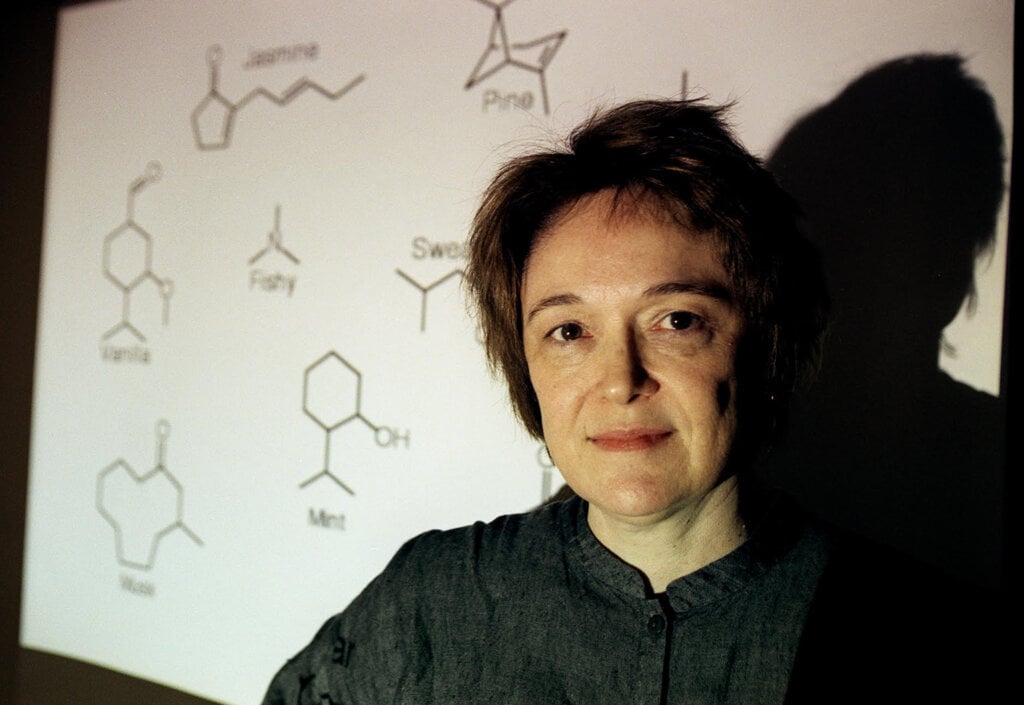

Linda Buck was fascinated by one seemingly simple question: how does our sense of smell work? Once she started to look for the answer, she didn’t let it go. She followed the olfactory process step by step to the very heart of what makes us human: our perceptions, preferences and memories.

Nasal lining, as seen in a coloured scanning electron micrograph (SEM), showing olfactory cells (red) surrounded by numerous cilia (hair-like projections, blue).

Image: Steve Gschmeissner / Science Source Images

Smell receptor. Transmission electron micrograph (TEM) of a section through the olfactory epithelium that lines the nasal cavity, showing an olfactory cell (smell receptor, red) and its cilia (hair-like projections).

Image: Steve Gschmeissner/Science Source

Born in Seattle in 1947, Linda Buck never imagined she would be a scientist, although she had a scientist’s curiosity. Her father (an electrical engineer) and her mother (a homemaker) loved puzzles and inventions, which may have led to her future career, since, as Buck sees it, science “is really puzzle-solving.” Her parents also allowed her to explore, encouraged her to think, and expected that she would do something worthwhile with her life.

It took Buck a while to figure out what her “something” would be. She went to the University of Washington to study psychology, but, uncertain whether she really wanted to be a psychotherapist, she left school to travel, taking classes intermittently.

A class in immunology sparked her interest in biology, and in 1975, at the age of 28, ten years after she began, she graduated with a B.S. in both microbiology and psychology.

Buck earned a PhD in immunology at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center in Dallas. She credits her thesis advisor, Ellen Vitetta, for teaching her how to do research. She then went to Columbia University, and ultimately to the lab of Richard Axel, a neuroscientist doing molecular studies of the nervous system of a sea snail.

Buck was fascinated by the brain’s cellular diversity, and found her ideal topic reading a paper on potential mechanisms underlying odour detection. It was a life-changing moment: the first time she had ever thought about the intriguing unsolved mystery of olfaction.

Nasopharynx surface as seen in a scanning electron micrograph (SEM). Shown here are tiny microvilli on the surface of a squamous nasal epithelial cell. The nasopharynx (nasal part of the pharynx) lies behind the nose and above the level of the soft palate.

Dennis Kunkel Microscopy / Science Source Images

Nasopharynx surface as seen in a scanning electron micrograph (SEM). Shown here are tiny microvilli on the surface of a squamous nasal epithelial cell. The nasopharynx (nasal part of the pharynx) lies behind the nose and above the level of the soft palate.

Dennis Kunkel Microscopy / Science Source Images

“How could humans and other mammals detect 10,000 or more odorous chemicals, and how could nearly identical chemicals generate different odour perceptions? In my mind, this was a monumental puzzle and an unparalleled diversity problem.”

Linda Buck

The first piece of the puzzle was figuring out how the nose detects odours. Buck embarked on the search for odour receptors in 1988, and worked intensely for three years. In results published in 1991, Buck and Axel pinpointed 1,000 types of olfactory receptors in mice, located in the back of the nose, on a spot called the olfactory epithelium. The receptors are protein molecules that bind to the molecules of certain odorants, allowing for the recognition of individual scents. While humans have far fewer of these receptors (350 versus 1,000), they work the same way for us.

Buck moved to Harvard University to solve another part of the puzzle. After solving the mystery of how the olfactory system detects odorants, she sought to discover how these receptor signals create the impression of different odours, based on their organisation in the brain.

With only 350 olfactory receptors, how can humans distinguish among 10,000 or more smells, some of which are nearly identical?

In 1999, Buck revealed the answer to be a complicated system in which each olfactory receptor detects more than one odorant and each odorant can be detected by more than one receptor. Working together, the receptors create a “combinatorial code” forming an “odorant pattern” to identify specific odours. This code underlies our ability to recognise more than 10,000 different odours, just as we can spell thousands of words with just 26 letters.

An odorant receptor protein is shown weaving in and out of the neuron surface. Balls indicate amino acids. Red balls indicate amino acids that are hypervariable among receptors.

Courtesy of Linda B. Buck

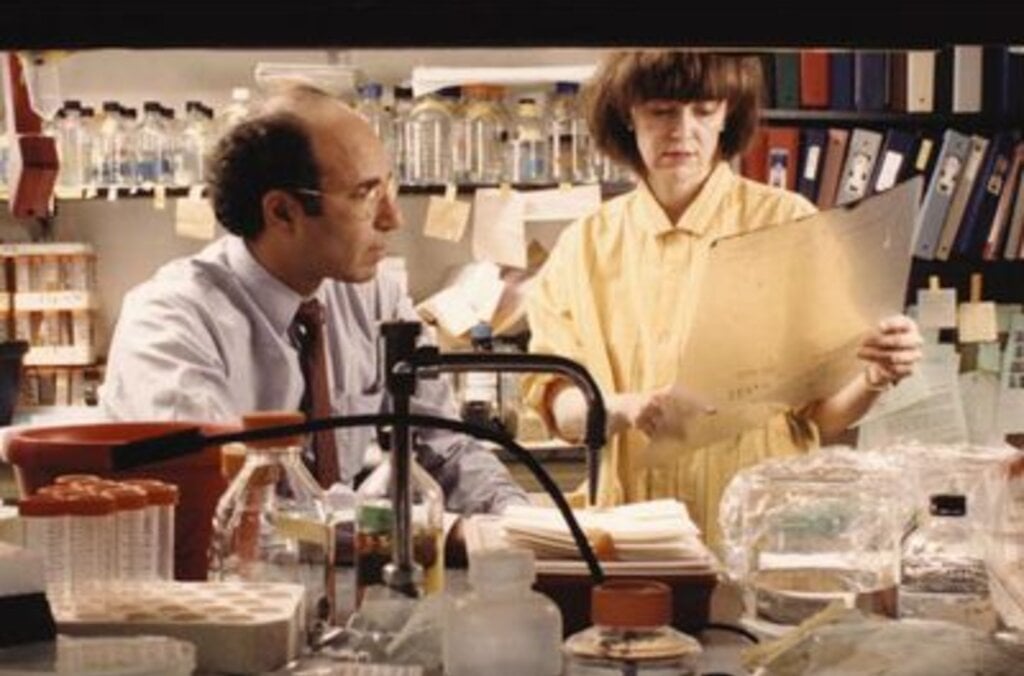

Linda Buck describes her research at a 2004 news conference.

Photo: Reuters

Buck next sought to understand how the reception of odour becomes perception and memory. How do we go from receiving odour signals in the nose to processing them in the brain’s olfactory cortex?

In 2001, at age 54, the year she became a full professor at Harvard, she published studies about how olfactory neurons are mapped in the cortex. She had started with the mechanism of perceiving smell in the nose and pushed onward into smell’s profound effects on the brain: memory, emotion, attraction, and aversion.

In 2002, two years before she and Axel received the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine, she went back to Seattle. She established a laboratory at the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Center, dedicated to continuing her exploration of the olfactory system.

“As a woman in science, I sincerely hope that my receiving a Nobel Prize will send a message to young women everywhere that the doors are open to them and that they should follow their dreams.”

Linda Buck

Buck was obsessed with smell. What she discovered has potential applications for treating people who’ve lost their appetite or sense of smell, but usefulness isn’t the point for Buck. She simply wants to understand, to solve a piece of one of the great puzzles of human biology: how we perceive and respond to the world.

“Do something that you’re obsessed with, that you just have to understand, because that’s where the joy comes from, and that also, I think, is where the great discoveries come from.”

Linda Buck

Transcript from an interview with the 2004 medicine laureates

Transcript from an interview with the 2004 Nobel Laureates in Physiology or Medicine, Richard Axel and Linda B. Buck on 11 December 2004, during the Nobel Week in Stockholm, Sweden.

Welcome to meet the Nobel Laureates in Physiology or Medicine 2004, Richard Axel and Linda Buck. First of course like everyone else, congratulations to the prize. You have heard this millions of times in the past days I suppose. This is the afternoon, the day after the big event, so what about the big event yesterday, what are the most memorable moments of the day, Linda?

Linda Buck: The whole thing was very dramatic and unusual, and it was wonderful to have my family and friends there. It was a once in a lifetime experience.

Richard Axel?

Richard Axel: I thought that the whole day, the ceremony, the formalism of the ceremony and the grandeur of the evening added a spectacular dimension to what we do, and what we do is try and understand how the world works, how the brain works and to have our work, which we do on a daily basis, celebrated in so grand a fashion, really added a very nice dimension.

One of the things that really strikes you when you read about your science is the huge proportion of one genome that is used for constructing the nose or the olfactory system. Linda Buck, how come, why do we use so much of our genome for the nose?

Linda Buck: I think the way evolution works is that if something happens and if it’s useful then it remains in the genome. I think that during evolution of the sense of smell, multiple genes were made, it was advantageous, and they were capped, and you see that some of the genes are disappearing, there are remnants of genes encoding candidate pheromone receptors in humans and those genes are for the most part intact in mice and most of them have become pseudo genes in humans. Now in addition to that though it does seem that in certain invertebrate organisms there are also very large gene families that are used for smell and so it does seem to be a strategy that has worked, perhaps been developed independently in different organisms …

But happened to be exactly the same systems, in …

Linda Buck: Yes, but the genes are not really related, they’re genes that encode proteins of the same type but are really quite different. So it does seem to be a strategy that’s perhaps been developed independently several times.

Was the sensory organ maybe the first … When you look upon evolution, the way to perceive, to react to the external world, chemotaxis came long before phototaxium and maybe phonotaxis if there is any phonotaxium in the biological world. Is that the right, that the smell, the senses of smell was the first one?

Richard Axel: Chemosensation as you say certainly is the first one. I mean back, every organism, even the most primitive and humble bacterium have to have a way to respond to sense what is in the world around them because that determines how they are going to survive, it determines what their food supply is, how they have to metabolise their food, it determines aversive environments. So all organisms have to have a way to sense the chemical environment and the way they sense the chemical environment has evolved and so we indeed sense it in a different way than does a bacterium but the principle of communicating and responding to the environment is very primitive.

When we come to higher, I shouldn’t call them higher or lower organisms but more complex organisms …

Linda Buck: You’ve got that from anthropology, is that right?

Anyhow, how is this perception of the chemical environment, how is it mediated into action, how can it be translated to action? What mechanisms is life using?

Linda Buck: I think in mammals and also in many invertebrate organisms the information travels through a series of relay stations, if you will, in the nervous system and that allows the information from hundreds or a thousand different receptors to be organised in progressively more sophisticated ways and also in different ways. In the mammalian cortex what we see is that there are distinct anatomical areas in the olfactory cortex that are getting information from the odorant receptor family in the nose and those different areas of the olfactory cortex send information to different areas of the brain. We think what maybe happening is that the information from the receptors is being organised, combined, or perhaps modulated in different ways in those different areas before being sent on to yet other brain areas. This parallel processing of information is something that is seen in other parts of the nervous system as well so you can take the same sensory information from the external world and then you can process it in different ways in different parts of the brain to use that information for different things.

And how do the animals or we perceive all this process? Is it through emotions?

Linda Buck: The information is targeted to different parts of the brain and some of those structures in the olfactory cortex send information on to higher cortical areas, both directly and indirectly through the thalamus, but in addition there are some parts of the olfactory cortex that send information to the hypothalamus and certain parts of the amygdala and those are parts of the brain that control physiological effects, emotional responses and instinctive behaviours. In fact, we think that using the sense of smell, and using molecular approaches, we can gain access to neurons and neural circuits in those very primitive parts of the brain and perhaps begin to obtain information about the neurons and the neural circuits that control instinctive behaviours and emotions.

Does that mean that the olfactory system is also sending signals to the brain that we are not aware of, through unconscious levels of our brain? What do you think Richard Axel?

Richard Axel: That’s a hard question to answer; I mean how do we know that there is the unconscious recognition of scent? We do know, as Linda pointed out, that smell is recognised by cells that project to different areas in the cortex and some of those areas, some of those areas are new brain, cognitive brain and others are old brain, emotive brain. One might think that the odours that activate emotive brain might illicit emotions and innate behavioural responses and neural endocrinal responses without the conscious awareness of those signals. For instance, in animals we know that certain odours can reorganise the time of puberty, can reorganise the menstrual cycle and can illicit or prevent mating. There are studies in humans which are far more difficult to control to suggest that there are olfactory driven changes in the menstrual cycle, there’s a very famous study out of Chicago suggesting that women in a dormitory tend to synchronise their cycles and that’s thought to be olfactory, but those studies are psychophysical not biophysical and they’re much more difficult to prove with certainty.

What about more everyday life events, is it possible that fear can smell and happiness can smell? That we can register emotions in the room without being really aware of it? Is that a too spectacular question?

Linda Buck: People talk about it, I think more in literature than in science, the smell of fear and so on and I don’t know, I think maybe that has to do with components of human sweat or it’s not really, it’s not something that we investigate really and I suppose …

But in just …

Linda Buck: … maybe in the future.

Because in one of your Nobel lectures or Nobel symposia, you talk about your great interest in trying to elucidate how subordination maybe mediated through smells and also aggressiveness and …

Linda Buck: We are actually looking, using mice, we’re using odours that have particular effects on the animals, we’re just starting to do that now. We’re looking at activation in the brain by a fox odour that causes a stereotype fear response. We’re also looking at effects of different kinds of odorants on the behaviour of the animal and looking at parts of the brain that are activated and we do see that mice don’t like skunk odour any better than we do and there are quite dramatic behavioural differences between their responses to skunk, skunk, fox odour and vanilla so they’ll actually try to get to an input tube that’s, through which there’s vanilla odour and they try to hide from the skunk. They try to hide from the skunk and in response to the fox odour; they just become paralysed with fear.

Do we know that useful things tend to be preserved throughout the biological fear and maybe …

Linda Buck: That’s right and it’s clear that in the hypothalamus … The hypothalamus is basically the major control centre of the brain, it’s very primitive, it’s there in animals, it’s there in human and it’s highly conserved in its structure and also in the genes are expressed there and in the neural circuits and most, if not all, instinctive behaviours and emotional responses are controlled by the hypothalamus.

And the hypothalamus has a direct contact with the nose?

Linda Buck: There are inputs from, yes; there are inputs from the nose. The hypothalamus actually collects information from all sensory systems, from the other parts of the brain and from the body. It gets input not only from the nervous system, that of course connects the entire body but also through the bloodstream. It measures the temperature, it measures the composition of the blood, it measures sex hormone levels, it controls the menstrual cycle, it controls the stress response. So it’s basically the main control system and of course because odours can cause stress, fear, pheromones and maybe some odours can control sexual behaviour, we can use the olfactory system to try to gain information about those circuits and start dissecting the neural circuits and the individual neurons including the genes that they express, that control those very basic emotional responses and behaviours. That’s where we’re going next.

Another fascinating information that comes from your science is how the olfactory system is translating scattered molecules of sense into an organised map in the brain, it turns into a physical map, Richard Axel, but who is watching the map inside your brain? How do you make sense out of a physical map from these molecules?

Richard Axel: That’s a central issue that neuroscientists would like to address and have been attempting to investigate for a very long time as you’ve heard me put it before. This is a central issue in all senses that is the way… There seems to be a conceptual thread that runs through the different senses and that is that in olfaction as well as in vision the image, whether it be a chemical in olfaction or a visual image in sight, is very complex and it needs to be deconstructed into its components before it can be re-established in the brain as something meaningful. So in vision for example, the individual components of a visual image, that is colour, movement, edges, form texture even at the level of the retina in the eye are deconstructed and carried to the brain by parallel pathways. They are relayed in different regions of the brain so there are regions of the brain that are responsive to movement and not colour, other regions responsive to edge and not movement and at some point, there must be an area which consists of ensembles of neurons that can put this information back together. Now the analogy to the olfactory system as a consequence of the efforts of a number of people including Linda, suggest that you transform chemical space into brain space in the very same way that a given odour, even a single molecular species in an odour, will have the capability of fitting into multiple different receptors and those receptors project to different points in the brain so that those points, the receptors that an odour can interact with and the points which they activate in the brain, form a signature and then as you point out, you’re left with the problem.

Who is watching?

Richard Axel: The problem of who looks down on these points? Who listens to the music, who sees the activation? As I’ve put it before, it’s an old problem, it’s the problem of the ghost and the machine and philosophers have been addressing this problem now since Plato.

Linda Buck: I think this is a challenge for neuroscience in the future and it’s been recognised for a very long time that we do not know how it is that neurons firing in different parts of the brain, active in different parts of the brain, somehow constitute a perception, a percept because it’s clear that not all the information is going to come together in a grandmother cell and when that cell is activated you think “grandmother”. There are indeed neurons that are activated through, in many different parts of the brain and somehow that constitutes a cohesive perception.

But do you really think …

Linda Buck: And there’s nobody looking, it’s the way it works. There’s no one who will be looking, it’s the way the brain works, and I think that it is a scientific problem in terms of how physically that might happen but it’s also a philosophical problem, a conceptual problem because I think it’s difficult for scientists to conceptualise how it is that neurons that are dispersed in different parts of the brain could form a percept and it could be that it’s just going to take some kind of a conceptual or philosophical step for people to say, That’s not a problem, we accept that.

So, the big enigma, our consciousness arising, is just that that is consciousness, all these things that happen in the brain together?

Linda Buck: Yes, it’s just very hard for people to accept that.

Richard Axel and Linda Buck, thank you very much for sharing your time and your fascinating thoughts and ideas about your science with us. Thank you.

Linda Buck: Thank you.

Richard Axel: Thank you.

Did you find any typos in this text? We would appreciate your assistance in identifying any errors and to let us know. Thank you for taking the time to report the errors by sending us an e-mail.

Press release

English

Swedish

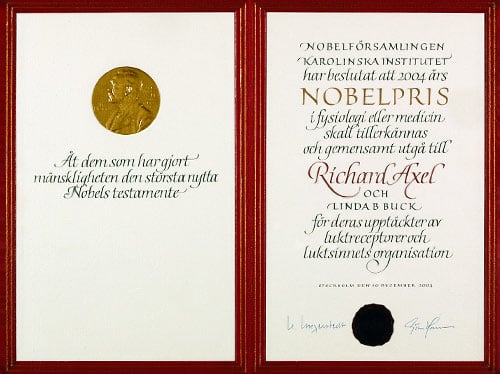

4 October 2004

The Nobel Assembly at Karolinska Institutet has today decided to award

The Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for 2004 jointly to

Richard Axel and Linda B. Buck

for their discoveries of “odorant receptors and the organization of the olfactory system”

Summary

The sense of smell long remained the most enigmatic of our senses. The basic principles for recognizing and remembering about 10,000 different odours were not understood. This year’s Nobel Laureates in Physiology or Medicine have solved this problem and in a series of pioneering studies clarified how our olfactory system works. They discovered a large gene family, comprised of some 1,000 different genes (three per cent of our genes) that give rise to an equivalent number of olfactory receptor types. These receptors are located on the olfactory receptor cells, which occupy a small area in the upper part of the nasal epithelium and detect the inhaled odorant molecules.

Each olfactory receptor cell possesses only one type of odorant receptor, and each receptor can detect a limited number of odorant substances. Our olfactory receptor cells are therefore highly specialized for a few odours. The cells send thin nerve processes directly to distinct micro domains, glomeruli, in the olfactory bulb, the primary olfactory area of the brain. Receptor cells carrying the same type of receptor send their nerve processes to the same glomerulus. From these micro domains in the olfactory bulb the information is relayed further to other parts of the brain, where the information from several olfactory receptors is combined, forming a pattern. Therefore, we can consciously experience the smell of a lilac flower in the spring and recall this olfactory memory at other times.

Richard Axel, New York, USA, and Linda Buck, Seattle, USA, published the fundamental paper jointly in 1991, in which they described the very large family of about one thousand genes for odorant receptors. Axel and Buck have since worked independent of each other, and they have in several elegant, often parallel, studies clarified the olfactory system, from the molecular level to the organization of the cells.

The olfactory system is important for life quality

When something tastes really good it is primarily activation of the olfactory system which helps us detect the qualities we regard as positive. A good wine or a sunripe wild strawberry activates a whole array of odorant receptors, helping us to perceive the different odorant molecules.

A unique odour can trigger distinct memories from our childhood or from emotional moments – positive or negative – later in life. A single clam that is not fresh and will cause malaise can leave a memory that stays with us for years, and prevent us from ingesting any dish, however delicious, with clams in it. To lose the sense of smell is a serious handicap – we no longer perceive the different qualities of food and we cannot detect warning signals, for example smoke from a fire.

Olfaction is of central importance for most species

All living organisms can detect and identify chemical substances in their environment. It is obviously of great survival value to be able to identify suitable food and to avoid putrid or unfit foodstuff. Whereas fish has a relatively small number of odorant receptors, about one hundred, mice – the species Axel and Buck studied – have about one thousand. Humans have a somewhat smaller number than mice; some of the genes have been lost during evolution.

Smell is absolutely essential for a newborn mammalian pup to find the teats of its mother and obtain milk – without olfaction the pup does not survive unaided. Olfaction is also of paramount importance for many adult animals, since they observe and interpret their environment largely by sensing smell. For example, the area of the olfactory epithelium in dogs is some forty times larger than in humans.

A large family of odorant receptors

The olfactory system is the first of our sensory systems that has been deciphered primarily using molecular techniques. Axel and Buck showed that three per cent of our genes are used to code for the different odorant receptors on the membrane of the olfactory receptor cells. When an odorant receptor is activated by an odorous substance, an electric signal is triggered in the olfactory receptor cell and sent to the brain via nerve processes. Each odorant receptor first activates a G protein, to which it is coupled. The G protein in turn stimulates the formation of cAMP (cyclic AMP). This messenger molecule activates ion channels, which are opened and the cell is activated. Axel and Buck showed that the large family of odorant receptors belongs to the G protein-coupled receptors (GPCR).

All the odorant receptors are related proteins but differ in certain details, explaining why they are triggered by different odorous molecules. Each receptor consists of a chain of amino acids that is anchored into the cell membrane and traverses it seven times. The chain creates a binding pocket where the odorant can attach. When that happens, the shape of the receptor protein is altered, leading to G protein activation.

One type of odorant receptor in each olfactory receptor cell

Independently, Axel and Buck showed that every single olfactory receptor cell expresses one and only one of the odorant receptor genes. Thus, there are as many types of olfactory receptor cells as there are odorant receptors. It was possible to show, by registering the electrical signals coming from single olfactory receptor cells, that each cell does not react only to one odorous substance, but to several related molecules – albeit with varying intensity.

Buck’s research group examined the sensitivity of individual olfactory receptor cells to specific odorants. By means of a pipette, they emptied the contents of each cell and showed exactly which odorant receptor gene was expressed in that cell. In this way, they could correlate the response to a specific odorant with the particular type of receptor carried by that cell.

Most odours are composed of multiple odorant molecules, and each odorant molecule activates several odorant receptors. This leads to a combinatorial code forming an “odorant pattern” – somewhat like the colours in a patchwork quilt or in a mosaic. This is the basis for our ability to recognize and form memories of approximately 10,000 different odours.

Olfactory receptor cells activate micro regions in the olfactory bulb

The finding that each olfactory receptor cell only expresses one single odorant receptor gene was highly unexpected. Axel and Buck continued by determining the organization of the first relay station in the brain. The olfactory receptor cell sends its nerve processes to the olfactory bulb, where there are some 2,000 well-defined microregions, glomeruli. There are thus about twice as many glomeruli as the types of olfactory receptor cells.

Axel and Buck independently showed that receptor cells carrying the same type of receptor converge their processes into the same glomerulus, and Axel’s research group used sophisticated genetic technology to demonstrate in mice the role of the receptor in this process. The convergence of information from cells with the same receptor into the same glomerulus demonstrated that also glomeruli exhibit remarkable specificity (see figure).

In the glomeruli we find not only the nerve processes from the olfactory receptor cells but also their contacts with the next level of nerve cells, the mitral cells. Each mitral cell is activated only by one glomerulus, and the specificity in the information flow is thereby maintained. Via long nerve processes, the mitral cells send the information to several parts of the brain. Buck showed that these nerve signals in turn reach defined micro regions in the brain cortex. Here the information from several types of odorant receptors is combined into a pattern characteristic for each odour. This is interpreted and leads to the conscious experience of a recognizable odour.

Pheromones and taste

The general principles that Axel and Buck discovered for the olfactory system appears to apply also to other sensory systems. Pheromones are molecules that can influence different social behaviours, especially in animals. Axel and Buck, independent of each other, discovered that pheromones are detected by two other families of GPCR, localized to a different part of the nasal epithelium. The taste buds of the tongue have yet another family of GPCR, which is associated with the sense of taste.

Reference

Buck, L. and Axel, R. (1991) Cell, vol. 65, 175-187.

High resolution image (jpg 1,5 Mb)

High resolution image (pdf 1,99 Mb)

Pressmeddelande: Nobelpriset i fysiologi eller medicin 2004

English

Swedish

4 oktober 2004

Nobelförsamlingen vid Karolinska Institutet har idag beslutat att

Nobelpriset i Fysiologi eller Medicin år 2004 gemensamt tilldelas

Richard Axel och Linda B. Buck

för deras upptäckter av ”luktreceptorer och luktsinnets organisation”

Sammanfattning

Luktsinnet var länge det mest gåtfulla av våra sinnen. Man förstod inte grundprinciperna för hur vi kan känna igen och minnas inte mindre än 10 000 olika dofter. Årets två Nobelpristagare i Fysiologi eller Medicin har löst denna gåta och i en serie revolutionerande arbeten klargjort hur vårt luktsinne fungerar. De upptäckte en stor genfamilj av närmare tusen olika gener (tre procent av våra gener), som ger upphov till lika många typer av luktreceptorer. Dessa sitter på luktreceptorcellerna som finns i ett litet område i övre delen av nässlemhinnan. Där kan de känna av de doftmolekyler som vi andas in.

Varje luktreceptorcell har bara en typ av luktreceptor, och var och en av dessa kan känna av ett begränsat antal doftämnen. Våra cirka tusen olika typer av luktreceptorceller är därför starkt specialiserade för enskilda doftämnen. Luktreceptorcellerna sänder tunna nervutskott direkt till avgränsade mikroregioner, glomeruli, i hjärnans primära luktområde, luktbulben. Varje sådan glomerulus aktiveras endast av utskott från en typ av luktreceptorcell. Från dessa mikroregioner i luktbulben sänds informationen vidare till andra delar av hjärnan. Här kombineras informationen från flera luktreceptorer så att ett mönster bildas. Det gör att vi medvetet kan uppleva exempelvis doften av en syren på försommaren, eller kan återkalla ett sådant doftminne vid andra tidpunkter.

Richard Axel, New York, USA, och Linda Buck, Seattle, USA, publicerade år 1991 tillsammans det grundläggande arbetet, där de påvisade den mycket stora familjen av luktreceptorgener. Axel och Buck har sedan arbetat parallellt och oberoende av varandra och har i flera eleganta arbeten klarlagt hur luktsystemet fungerar, från molekylär nivå till hur cellerna är organiserade.

Luktsinnet viktigt för vår livskvalitet

När något smakar riktigt gott är det framför allt luktsinnet som har aktiverats och hjälpt oss att upptäcka de olika kvaliteter som vi uppfattar som positiva. Ett gott vin eller ett solmoget smultron aktiverar ett helt batteri av luktreceptorer. Dessa hjälper oss att förnimma olika doftämnen.

En unik doft kan framkalla distinkta minnen från vår barndom eller från känsloladdade händelser – positiva eller negativa. En enstaka mussla som inte är fräsch utan orsakar illamående kan lämna ett bestående minne över många år, ett minne som gör att vi inte kan förmå oss att äta någon rätt som innehåller musslor – hur läcker den än må vara. Att förlora luktsinnet är ett allvarligt handikapp – då kan man inte längre uppfatta matens olika kvaliteter eller olika varningssignaler, exempelvis brandrök.

Lukten central för de flesta arter

Alla levande varelser har förmågan att upptäcka och identifiera kemiska ämnen i omgivningen. Att kunna identifiera lämplig föda och undvika mat som är härsken eller otjänlig som föda har naturligtvis ett stort överlevnadsvärde. Medan fiskar har ett ganska litet antal luktreceptorer, cirka hundra, har möss – som Axel och Buck arbetade med – omkring tusen. Vi människor har något färre än möss, och några av generna för luktreceptorer har förlorats under evolutionen.

För en nyfödd däggdjursunge är lukten central för att den till exempel ska kunna hitta moderns spenar och få mjölk – utan luktsinne överlever den normalt inte. För många vuxna djur spelar luktsinnet också en helt avgörande roll; till stor del lever de och tolkar omvärlden genom sitt luktsinne. Hundar har exempelvis ett cirka 40 gånger större område i näsan avdelat för luktreceptorer än vad människor har.

Den stora genfamiljen av luktreceptorer

Luktsinnet är det första sinnessystem vars funktion har kartlagts främst med molekylära tekniker. Axel och Buck visade att tre procent av våra gener används för att producera de olika luktreceptorerna, som finns på ytan av luktreceptorcellerna. När en luktreceptor aktiveras av ett doftämne leder det till att luktreceptorcellen stimuleras och skickar en elektrisk signal via sina utskott till hjärnan. Varje luktreceptor påverkar först ett G-protein, som den är direkt kopplad till. G-proteinet aktiverar i sin tur bildningen av en budbärarmolekyl inne i cellen, cAMP (cykliskt AMP). Sedan påverkar cAMP jonkanaler så att dessa öppnas och cellen aktiveras. Axel och Buck kartlade den mycket stora genfamiljen av luktreceptorer och visade att den tillhör gruppen G-protein-kopplade receptorer, GPCR.

Alla de cirka tusen olika luktreceptorerna är besläktade proteiner som skiljer sig åt i vissa detaljer, vilket förklarar att de kan aktiveras av olika doftämnen. De består av en lång kedja av aminosyror, som är förankrad i cellmembranet och passerar genom detta sju gånger. Kedjan skapar ett bindningställe till vilket doftämnet kan knytas. När doftämnet binds ändras proteinets form så att G-proteinet aktiveras.

En sorts luktreceptor i varje luktreceptorcell

Axel och Buck visade oberoende av varandra att varje enskild luktreceptorcell enbart uttrycker en av de närmare tusen olika luktreceptorgenerna. Vi har alltså lika många typer av luktreceptorceller som luktreceptorer. Genom att registrera de elektriska signalerna från enskilda luktreceptorceller kunde de visa att varje cell inte reagerar enbart på ett doftämne utan på flera snarlika molekyler – dock med varierande känslighet.

Bucks forskargrupp studerade olika luktreceptorcellers känslighet för olika doftämnen. Med hjälp av en pipett tömde man sedan de enskilda cellerna på sitt innehåll och kunde visa exakt vilken gen som var uttryckt i den undersökta cellen. På så sätt kunde man sluta sig till vilka doftämnen som aktiverar en enskild receptormolekyl.

De flesta lukter är sammansatta av flera doftämnen, och varje doftämne aktiverar flera olika luktreceptorceller. Därmed får vi en kombinationskod som kan bilda olika “luktmönster” – på motsvarande sätt som färgerna i ett lapptäcke eller i en mosaik. Detta gör att vi kan känna av och forma minnesbilder av cirka 10 000 olika dofter.

Luktreceptorceller aktiverar mikroregioner i hjärnans luktbulb

Fyndet att varje luktreceptorcell bara uttrycker en enda luktreceptorgen var högst oväntat. Axel och Buck gick vidare med att undersöka hur den första omkopplingsstationen i hjärnan är organiserad. Luktreceptorcellerna sänder sina utskott till luktbulben, där det finns cirka 2 000 väl avgränsade mikroregioner, glomeruli. De är alltså ungefär dubbelt så många som antalet typer av luktreceptorceller.

Axel och Buck visade oberoende av varandra att luktreceptorceller som uttrycker samma luktreceptor sänder ut nervutskott som sammanstrålar i en gemensam glomerulus. Axels forskargrupp använde sig av avancerad genetisk teknologi för att i möss påvisa luktreceptorernas roll i denna process. Att nervutskott från celler med samma luktreceptor kopplas till samma glomerulus ledde till insikten att glomeruli är höggradigt specialiserade (se figur).

I dessa glomeruli finns inte bara nervtrådarna från luktreceptorcellerna utan också utskott från nästa lager av nervceller i luktbulben, mitralceller. Varje sådan mitralcell aktiveras endast från en glomerulus och bibehåller därmed sin specifika information. Via sina långa nervutskott skickar de information till flera områden i hjärnan om vilken luktreceptortyp som har aktiverats. Buck visade att dessa nervsignaler i sin tur går till specifika mikroregioner i hjärnbarken. Här kombineras informationen från flera olika typer av receptorer till ett mönster som är typiskt för varje doft. Detta tolkas slutligen till den medvetna upplevelsen av en viss igenkännbar doft.

Feromoner och smaksinnet

Många av de principer som gäller för luktsinnet gäller också för andra sinnen. Feromoner är ämnen som kan påverka olika typer av beteenden, främst hos djur. Axel och Buck har, oberoende av varandra, påvisat att feromoner kan detekteras av två andra GPCR-familjer, som finns i en helt annan del av nässlemhinnan. På tungans smaklökar finns ytterligare en familj av GPCR som är kopplade till smaksinnet.

Referens

Buck, L. and Axel, R. (1991) Cell, vol. 65, 175-187.

Linda B. Buck – Documentary

Linda B. Buck – Prize presentation

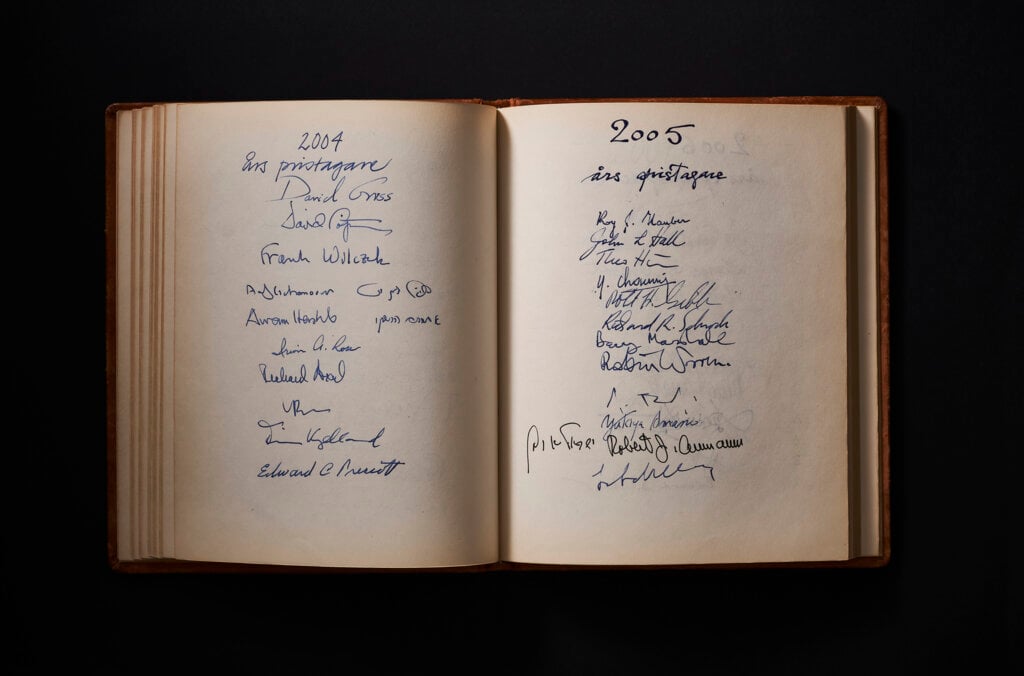

Watch a video clip of the 2004 Nobel Laureate in Physiology or Medicine, Linda B. Buck, receiving her Nobel Prize medal and diploma during the Nobel Prize Award Ceremony at the Concert Hall in Stockholm, Sweden, on 10 December 2004.

Richard Axel – Curriculum Vitae

| Richard Axel, born July 2, 1946, New York, NY, USA | |

| Address: | Howard Hughes Medical Institute, Columbia University, Hammer Health Sciences Center, 701 West 168th Street, Room 1014, New York, NY 10032, USA |

| Academic Education and Appointments | |

| 1967 | A.B. Columbia University, New York, NY |

| 1970 | M.D. Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Baltimore, MD |

| 1978 | Professor, Pathology and Biochemistry, Columbia University |

| 1984- | Investigator, Howard Hughes Medical Institute, Columbia University |

| 1999- | University Professor, Columbia University |

| Selected Honours and Awards | |

| 1969 | The Johns Hopkins Medical Society Research Award |

| 1983 | The Eli Lilly Award |

| 1983 | Member, the National Academy of Sciences |

| 1983 | Member, the American Academy of Arts and Sciences |

| 1984 | The New York Academy of Sciences Award in Biological and Medical Sciences |

| 1989 | The Richard Lounsbery Award, National Academy of Sciences |

| 1996 | The Unilever Science Award, with Dr. Linda Buck |

| 1997 | New York City Mayor’s Award for Excellence in Science and Technology |

| 1998 | Bristol-Myers Squibb Award for Distinguished Achievement in Neuroscience Research |

| 1999 | The Alexander Hamilton Award, Columbia University |

| 2001 | NY Academy of Medicine Medal for Distinguished Contributions in Biomedical Sciences |

| 2003 | The Gairdner Foundation International Award for Achievement in Neuroscience |

| 2003 | The Perl/UNC Neuroscience Prize, with Dr. Linda Buck |

| 2003 | Member, the American Philosophical Society |

The Nobel Assembly at Karolinska Institutet

Richard Axel – Prize presentation

Watch a video clip of the 2004 Nobel Laureate in Physiology or Medicine, Richard Axel, receiving his Nobel Prize medal and diploma during the Nobel Prize Award Ceremony at the Concert Hall in Stockholm, Sweden, on 10 December 2004.

Richard Axel – Nobel Lecture

Richard Axel held his Nobel Lecture December 8, 2004, at Sal Adam, Berzeliuslaboratoriet, Karolinska Institutet.

Lecture Slides

Pdf 7.19 MB

Read the Nobel Lecture

Pdf 1.38 MB

Richard Axel – Nobel diploma

Copyright © The Nobel Foundation 2004

Calligrapher: Susan Duvnäs