I was born in the city of Hamadan [northwestern Iran] in 1947. My family were academics and practising Muslims. At the time of my birth my father was the head of Hamedan’s Registry Office …

Shirin Ebadi – Speed read

Shirin Ebadi was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize for her efforts for democracy and human rights, especially for the rights of women and children.

Full name: Shirin Ebadi

Born: 21 June 1947, Hamadan, Iran

Date awarded: 10 October 2003

The first woman Muslim peace laureate

Shirin Ebadi was one of Iran’s first female judges. Dismissed from her post in 1979 after Khomeini’s revolution, she later opened a private law practice and served as defence council for dissidents. In 2000, she herself was arrested because of her criticism of the regime. Ebadi joined the campaign for fundamental human rights, and women’s and children’s rights in particular. She helped to found organisations that put these issues on the agenda and wrote books suggesting changes to Iranian inheritance and divorce legislation. She also advocated taking political power out of the hands of the clergy and separating religion and state. The Norwegian Nobel Committee’s decision to honour Ebadi reflected a desire to ease tensions between the Islamic world and the West after the terrorist attack on the USA on 11 September 2001. The decision was also a show of support for the Iranian reform movement.

“Shirin Ebadi underlines that the dialogue between different cultures in the world must be founded on values they have in common. There need be no fundamental conflict between Islam and Christianity.”

Ole Danbolt Mjøs, Presentation Speech, 10 December 2003.

“Undoubtedly, my selection will be an inspiration to the masses of women who are striving to realize their rights, not only in Iran but throughout the region – rights taken away from them through the passages of history.”

Shirin Ebadi, Nobel Prize lecture, 10 December 2003.

Shirin Ebadi – a human rights activist

In 1994, Ebadi co-founded the Association for Support of Children’s Rights. Its aim is to ensure Iran’s compliance with the UN convention on children’s rights, which the Iranian Government signed that same year. Apolitical and independent, the association works to improve children’s nutrition, health and education, and the environment in which they are reared. Ebadi also helped to establish a crisis centre for children and the Human Rights Defence Centre.

| Human rights Rights that apply to all persons regardless of gender, race, ethnicity, religious affiliation or nationality. The most important are the rights enshrined in the UN Declaration of Human Rights, adopted in 1948. |

| UN convention on the rights of the child Adopted in 1959 to give children particular protection so that they can grow up safely, no matter where in the world they live. Children shall be ensured access to food, shelter and education, and shall be protected from participation in child labour. |

“Hardliners who run the judiciary will see it as outsiders now trying to intervene in Iranian politics. It is an embarrassment to them to see someone they have vilified held up as a shining example.”

BBC Tehran Correspondent Jim Muir, 10 October 2003.

Jubilation and scepticism

The news that Ebadi had received the Nobel Peace Prize was met with jubilation by the Iranian reform movement and with disapproval by the theocracy. President Khatami feared that the prize would be misused by Iran’s enemies and claimed that “the Nobel Peace Prize was not very important. The ones that count are the Nobel Prizes in science and literature.” One conservative newspaper maintained that the award was meant as an insult to Islamic countries, while another viewed it as part of a Western, anti-religious campaign.

Continued struggle for freedom

After she received the peace prize, Shirin Ebadi continued to defend people who were persecuted by the Iranian regime, but at a cost. In 2008 the authorities closed down Ebadi’s centre for human rights, and when president Mahmoud Ahmadinejad was re-elected the following year, she left for exile in Great Britain. She described the Iranian elections as undemocratic and dissociated herself from the widespread suppression of the opposition. The authorities in Teheran responded by assaulting Ebadi’s husband and confiscating the Nobel Peace Prize medal. They also froze her bank account and accused her of tax evasion.

Learn more

Disclaimer: Every effort has been made by the publisher to credit organisations and individuals with regard to the supply of photographs. Please notify the publishers regarding corrections.

Shirin Ebadi – Photo gallery

Shirin Ebadi receiving her Nobel Prize from Ole Danbolt Mjøs, Chairman of the Norwegian Nobel Committee, 10 December 2003.

Copyright © Pressens Bild AB 2003, SE-112 88 Stockholm, Sweden, telephone: +46-8-738 38 00 Photo: John McConnico

Nobel Peace Prize Award ceremony in Oslo City Hall on 10 December 2003.

© Knudsens fotosenter/Dextra Photo, Norsk Teknisk Museum.

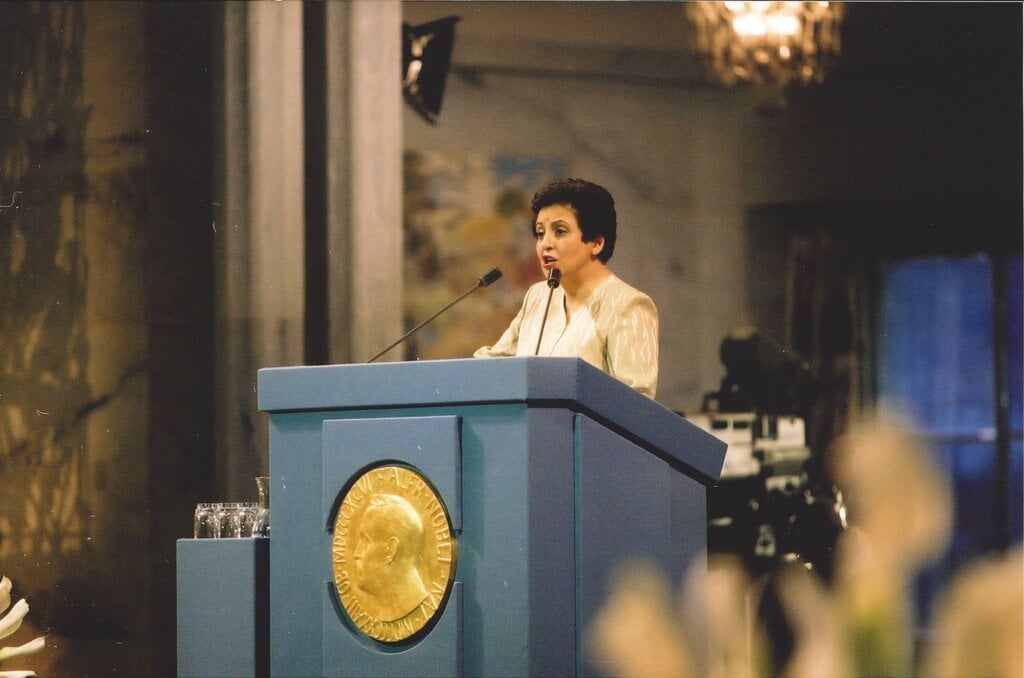

Shirin Ebadi presenting her Nobel Lecture during the 2003 Nobel Peace Prize Award Ceremony in the Oslo City Hall. Shirin Ebadi accepted the prize on behalf of her fellow Iranians, Muslim women everywhere and those who struggle for human rights.

Copyright © Pressens Bild AB 2003, SE-112 88 Stockholm, Sweden, telephone: +46-8-738 38 00 Photo: John McConnico

Shirin Ebadi presenting her Nobel Lecture during the 2003 Nobel Peace Prize Award Ceremony in the Oslo City Hall.

© Knudsens fotosenter/Dextra Photo, Norsk Teknisk Museum.

Norway's Crown Prince Haakon, Nobel Laureate Shirin Ebadi, Queen Sonja of Norway, Crown Princess Mette-Marit, and Chairman of the Norwegian Nobel Committee Ole Danbolt Mjøs in the Oslo City Hall.

© Pressens Bild AB 2003, S-112 88 Stockholm, Sweden, telephone: +46(0)87383800. Photo: Tor Richardsen

Shirin Ebadi during a press conference at the Norwegian Nobel Institute, December 2003.

© Knudsens fotosenter/Dextra Photo, Norsk Teknisk Museum.

Shirin Ebadi watching photos of previos peace laureates in the Committee room at the Norwegian Nobel Institute in Oslo, Norway, December 2003.

© Knudsens fotosenter/Dextra Photo, Norsk Teknisk Museum.

Shirin Ebadi in front of a painting of Alfred Nobel in the Nobel suite of Grand Hotel, Oslo, Norway, December 2003.

© Knudsens fotosenter/Dextra Photo, Norsk Teknisk Museum.

Iranian human rights activist, Shirin Ebadi, waves to some 4,000 flag-waving children greeting her outside Oslo City Hall before the 2003 Nobel Peace Prize Award Ceremony on December 10.

© Pressens Bild AB 2003, S-112 88 Stockholm, Sweden, telephone: +46(0)87383800. Photo: Odd Andersen

Well-wishers outside the hotel where the Iranian human rights activist and 2003 Nobel Peace Prize Laureate Shirin Ebadi stayed in Oslo, Norway during the Nobel Festivities.

© Pressens Bild AB 2003, S-112 88 Stockholm, Sweden, telephone: +46(0)87383800. Photo: Odd Andersen

Shirin Ebadi during her visit to the Nobel Peace Center in October 2006.

Copyright © Nobel Peace Center 2006

Photo: Kirsti Svenning

Shirin Ebadi signing the guest book at the Nobel Peace Center in October 2006.

Copyright © Nobel Peace Center 2006

Photo: Kirsti Svenning

Shirin Ebadi was the main speaker at a seminar on women's rights in Muslim countries at the Nobel Peace Center in October 2006.

© Nobel Peace Center 2006 Photo: Kirsti Svenning

Shirin Ebadi at a seminar on women's rights in Muslim countries at the Nobel Peace Center in October 2006.

Copyright © Nobel Peace Center 2006 Photo: Hamid Nokhostin

Shirin Ebadi – Prize presentation

Shirin Ebadi – Biographical

I was born in the city of Hamadan [northwestern Iran] in 1947. My family were academics and practising Muslims. At the time of my birth my father was the head of Hamedan’s Registry Office. My father, Mohammad Ali Ebadi, one of the first lecturers in commercial law, had written several books. He passed away in 1993.

I spent my childhood in a family filled with kindness and affection. I have two sisters and a brother all of whom are highly educated. My mother dedicated all her time and devotion to our upbringing.

I came to Tehran with my family when I was a one year old and have since been a resident in the capital. I began my education at Firuzkuhi primary school and went on to Anoshiravn Dadgar and Reza Shah Kabir secondary schools for my higher education. I sat the Tehran University entrance exams and gained a place at the Faculty of Law in 1965. I received my law degree in three-and-a-half years, and immediately sat the entrance exams for the Department of Justice. After a six-month apprenticeship in adjudication, I began to serve officially as a judge in March 1969. While serving as a judge, I continued my education and obtained a doctorate with honours in private law from Tehran University in 1971.

I held a variety of positions in the Justice Department. In 1975, I became the President of Bench 24 of the [Tehran] City Court. I am the first woman in the history of Iranian justice to have served as a judge. Following the victory of the Islamic Revolution in February 1979, since the belief was that Islam forbids women to serve as judges, I and other female judges were dismissed from our posts and given clerical duties. They made me a clerk in the very court I once presided over. We all protested. As a result, they promoted all former female judges, including myself, to the position of “experts” in the Justice Department. I could not tolerate the situation any longer, and so put in a request for early retirement. My request was accepted. Since the Bar Association had remained closed for some time since the revolution and was being managed by the Judiciary, my application for practising law was turned down. I was, in effect, housebound for many years. Finally, in 1992 I succeeded in obtaining a lawyer’s licence and set up my own practice.

I used my time of unemployment to write several books and had many articles published in Iranian journals. After receiving my lawyer’s licence I accepted to defend many cases. Some were national cases. Among them, I represented the families of the serial murders victims (the family of Dariush and Parvaneh Foruhar) and Ezzat Ebrahiminejad, who were killed during the attack on the university dormitory. I also participated in some press-related cases. I took on a large number of social cases, too, including child abuse. Recently I agreed to represent the mother of Mrs Zahra Kazemi, a photojournalist killed in Iran.

I also teach at university. Each year, a number of students from outside Iran join my human rights training courses.

I am married. My husband is an electrical engineer. We have two daughters. One is 23 years old. She is studying for a doctorate in telecommunications at McGill University in Canada. The other is 20 years old and is in her third year at Tehran University where she reads law.

| Social Activities | |

| – | Leading several research projects for the UNICEF office in Tehran. |

| – | Cofounder of the Association for Support of Children’s Rights, 1995. I was the association’s president until 2000, and have continued to assist them as legal adviser. Currently the association has over 500 active members. |

| – | Providing various stages of free tuition in children’s rights and human rights. |

| – | Cofounder of the Human Rights Defence Centre with four defence lawyers, 2001. I am the centre’s president. |

| – | Delivering over 30 lectures to university and academic conferences and seminars on human rights. The lectures have been delivered in Iran, France, Belgium, Sweden, Switzerland, Britain and America. |

| – | Representing several journalists or their families, accused or sentenced in relation to freedom of expression. They include Habibollah Peyman (for writing articles and delivering speeches on freedom of expression); Abbas Marufi, the editor-in-chief of the monthly Gardoun (for publishing several interviews and poems); Faraj Sarkuhi (editor-in-chief of Adineh monthly). |

| – | Representing families of serial murder victims (the Foruhar family). |

| – | Representing the family of Ezzat Ebrahiminejad, murdered in the 9 July 1999 attack on the university dormitory. |

| – | Representing the mother of Arin Golshani, a child separated from her mother as a consequence of the child custody law. She was found tortured to death at the home of her stepmother. |

| – | Proposing to the Islamic Consultative Assembly (Majlis) to ratify a law on prohibiting all forms of violence against children; as a result the law was promptly debated and ratified in the summer of 2002. |

| Publications | |

| Books | |

| – | Criminal Laws, Tehran 1972. Published by Bank Melli of Iran (Professor Rahnama; Professor Abdolhoseyn Aliabadi). |

| – | The Rights of the Child; A study in the legal aspects of children’s rights in Iran, 1987. Translated into English by Mohammad Zamiran. Published by UNICEF, 1993. |

| – | Medical Laws; Tehran, 1988. Published by Zavar. |

| – | Young Workers, Tehran, 1989. Published by Roshangaran. |

| – | Copyright Laws, Tehran, 1989. Published by Roshangaran. |

| – | Architectural Laws, Tehran, 1991. Published by Roshangaran. |

| – | The Rights of Refugees, Tehran, 1993. Published by Ganj-e Danesh. |

| – | History and Documentation of Human Rights in Iran, Tehran, 1993. Published by Roshangaran. |

| – | Tradition and Modernity, Tehran 1995. Written by Mohammad Zamiran, Shirin Ebadi. Published by Ganj-e Danesh. |

| – | Children’s Comparative Law, Tehran, 1997. Published by Kanoun (This book was translated into English by Mr Hamid Marashi, and published by UNICEF in Tehran in 1998). |

| – | The Rights of Women, Tehran, 2002. Published by Ganj-e Danesh. |

| * Details provided are taken from the original publications. | |

| Articles | |

| – | “The Child and Family Law”; A series of articles appearing in the Encyclopedia Iranica. Published by Columbia University. |

| – | “The Rights of Parents”; Article published in the journal Studies in the Social Impacts of Biotechnology. Published by CNRS, France |

| – | “Women and Legal Forms of Violence in Iran”; Article published in the Bonyad Iran journal in Paris on the subject of violence. |

| – | Over 70 articles on various aspects of human rights which have appeared in various publications in Iran. Some have been translated into English. They were presented at CRC [Convention on the Rights of the Child], a seminar organized by UNICEF in 1997. |

| – | Articles published in various weeklies, including Fekr-e Now New Ideas, on various aspects of laws relating to women. |

| Prizes and Accolades | |

| 1. | An official Human Rights Watch observer, 1996. |

| 2. | The selection of The Rights of the Child as Book of the Year by the Culture and Islamic Guidance Ministry. |

| 3. | Recipient of the Rafto Human Rights Foundation prize for human rights activities, Norway 2001. |

| 4. |

The Nobel Peace Prize, Norway 2003. |

This autobiography/biography was written at the time of the award and later published in the book series Les Prix Nobel/ Nobel Lectures/The Nobel Prizes. The information is sometimes updated with an addendum submitted by the Laureate.

Shirin Ebadi – Nobel Lecture

Shirin Ebadi held her Nobel Lecture December 10, 2003, in the Oslo City Hall, Norway.

Farsi

Pdf 326 kB

In the name of the God of Creation and Wisdom

Your Majesty, Your Royal Highnesses, Honourable Members of the Norwegian Nobel Committee, Excellencies, Ladies and Gentlemen,

I feel extremely honoured that today my voice is reaching the people of the world from this distinguished venue. This great honour has been bestowed upon me by the Norwegian Nobel Committee. I salute the spirit of Alfred Nobel and hail all true followers of his path.

This year, the Nobel Peace Prize has been awarded to a woman from Iran, a Muslim country in the Middle East.

Undoubtedly, my selection will be an inspiration to the masses of women who are striving to realize their rights, not only in Iran but throughout the region – rights taken away from them through the passage of history. This selection will make women in Iran, and much further afield, believe in themselves. Women constitute half of the population of every country. To disregard women and bar them from active participation in political, social, economic and cultural life would in fact be tantamount to depriving the entire population of every society of half its capability. The patriarchal culture and the discrimination against women, particularly in the Islamic countries, cannot continue for ever.

Honourable members of the Norwegian Nobel Committee!

As you are aware, the honour and blessing of this prize will have a positive and far-reaching impact on the humanitarian and genuine endeavours of the people of Iran and the region. The magnitude of this blessing will embrace every freedom-loving and peace-seeking individual, whether they are women or men.

I thank the Norwegian Nobel Committee for this honour that has been bestowed upon me and for the blessing of this honour for the peace-loving people of my country.

Today coincides with the 55th anniversary of the adoption of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights; a declaration which begins with the recognition of the inherent dignity and the equal and inalienable rights of all members of the human family, as the guarantor of freedom, justice and peace. And it promises a world in which human beings shall enjoy freedom of expression and opinion, and be safeguarded and protected against fear and poverty.

Unfortunately, however, this year’s report by the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), as in the previous years, spells out the rise of a disaster which distances mankind from the idealistic world of the authors of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. In 2002, almost 1.2 billion human beings lived in glaring poverty, earning less than one dollar a day. Over 50 countries were caught up in war or natural disasters. AIDS has so far claimed the lives of 22 million individuals, and turned 13 million children into orphans.

At the same time, in the past two years, some states have violated the universal principles and laws of human rights by using the events of 11 September and the war on international terrorism as a pretext. The United Nations General Assembly Resolution 57/219, of 18 December 2002, the United Nations Security Council Resolution 1456, of 20 January 2003, and the United Nations Commission on Human Rights Resolution 2003/68, of 25 April 2003, set out and underline that all states must ensure that any measures taken to combat terrorism must comply with all their obligations under international law, in particular international human rights and humanitarian law. However, regulations restricting human rights and basic freedoms, special bodies and extraordinary courts, which make fair adjudication difficult and at times impossible, have been justified and given legitimacy under the cloak of the war on terrorism.

The concerns of human rights’ advocates increase when they observe that international human rights laws are breached not only by their recognized opponents under the pretext of cultural relativity, but that these principles are also violated in Western democracies, in other words countries which were themselves among the initial codifiers of the United Nations Charter and the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. It is in this framework that, for months, hundreds of individuals who were arrested in the course of military conflicts have been imprisoned in Guantanamo, without the benefit of the rights stipulated under the international Geneva conventions, the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and the [United Nations] International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights.

Moreover, a question which millions of citizens in the international civil society have been asking themselves for the past few years, particularly in recent months, and continue to ask, is this: why is it that some decisions and resolutions of the UN Security Council are binding, while some other resolutions of the council have no binding force? Why is it that in the past 35 years, dozens of UN resolutions concerning the occupation of the Palestinian territories by the state of Israel have not been implemented promptly, yet, in the past 12 years, the state and people of Iraq, once on the recommendation of the Security Council, and the second time, in spite of UN Security Council opposition, were subjected to attack, military assault, economic sanctions, and, ultimately, military occupation?

Ladies and Gentlemen,

Allow me to say a little about my country, region, culture and faith.

I am an Iranian. A descendent of Cyrus The Great. The very emperor who proclaimed at the pinnacle of power 2500 years ago that “… he would not reign over the people if they did not wish it.” And [he] promised not to force any person to change his religion and faith and guaranteed freedom for all. The Charter of Cyrus The Great is one of the most important documents that should be studied in the history of human rights.

I am a Muslim. In the Koran the Prophet of Islam has been cited as saying: “Thou shalt believe in thine faith and I in my religion”. That same divine book sees the mission of all prophets as that of inviting all human beings to uphold justice. Since the advent of Islam, too, Iran’s civilization and culture has become imbued and infused with humanitarianism, respect for the life, belief and faith of others, propagation of tolerance and compromise and avoidance of violence, bloodshed and war. The luminaries of Iranian literature, in particular our Gnostic literature, from Hafiz, Mowlavi [better known in the West as Rumi] and Attar to Saadi, Sanaei, Naser Khosrow and Nezami, are emissaries of this humanitarian culture. Their message manifests itself in this poem by Saadi:

“The sons of Adam are limbs of one another

Having been created of one essence”.

“When the calamity of time afflicts one limb

The other limbs cannot remain at rest”.

The people of Iran have been battling against consecutive conflicts between tradition and modernity for over 100 years. By resorting to ancient traditions, some have tried and are trying to see the world through the eyes of their predecessors and to deal with the problems and difficulties of the existing world by virtue of the values of the ancients. But, many others, while respecting their historical and cultural past and their religion and faith, seek to go forth in step with world developments and not lag behind the caravan of civilization, development and progress. The people of Iran, particularly in the recent years, have shown that they deem participation in public affairs to be their right, and that they want to be masters of their own destiny.

This conflict is observed not merely in Iran, but also in many Muslim states. Some Muslims, under the pretext that democracy and human rights are not compatible with Islamic teachings and the traditional structure of Islamic societies, have justified despotic governments, and continue to do so. In fact, it is not so easy to rule over a people who are aware of their rights, using traditional, patriarchal and paternalistic methods.

Islam is a religion whose first sermon to the Prophet begins with the word “Recite!” The Koran swears by the pen and what it writes. Such a sermon and message cannot be in conflict with awareness, knowledge, wisdom, freedom of opinion and expression and cultural pluralism.

The discriminatory plight of women in Islamic states, too, whether in the sphere of civil law or in the realm of social, political and cultural justice, has its roots in the patriarchal and male-dominated culture prevailing in these societies, not in Islam. This culture does not tolerate freedom and democracy, just as it does not believe in the equal rights of men and women, and the liberation of women from male domination (fathers, husbands, brothers …), because it would threaten the historical and traditional position of the rulers and guardians of that culture.

One has to say to those who have mooted the idea of a clash of civilizations, or prescribed war and military intervention for this region, and resorted to social, cultural, economic and political sluggishness of the South in a bid to justify their actions and opinions, that if you consider international human rights laws, including the nations’ right to determine their own destinies, to be universal, and if you believe in the priority and superiority of parliamentary democracy over other political systems, then you cannot think only of your own security and comfort, selfishly and contemptuously. A quest for new means and ideas to enable the countries of the South, too, to enjoy human rights and democracy, while maintaining their political independence and territorial integrity of their respective countries, must be given top priority by the United Nations in respect of future developments and international relations.

The decision by the Nobel Peace Committee to award the 2003 prize to me, as the first Iranian and the first woman from a Muslim country, inspires me and millions of Iranians and nationals of Islamic states with the hope that our efforts, endeavours and struggles toward the realization of human rights and the establishment of democracy in our respective countries enjoy the support, backing and solidarity of international civil society. This prize belongs to the people of Iran. It belongs to the people of the Islamic states, and the people of the South for establishing human rights and democracy.

Ladies and Gentlemen

In the introduction to my speech, I spoke of human rights as a guarantor of freedom, justice and peace. If human rights fail to be manifested in codified laws or put into effect by states, then, as rendered in the preamble of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, human beings will be left with no choice other than staging a “rebellion against tyranny and oppression”. A human being divested of all dignity, a human being deprived of human rights, a human being gripped by starvation, a human being beaten by famine, war and illness, a humiliated human being and a plundered human being is not in any position or state to recover the rights he or she has lost.

If the 21st century wishes to free itself from the cycle of violence, acts of terror and war, and avoid repetition of the experience of the 20th century – that most disaster-ridden century of humankind, there is no other way except by understanding and putting into practice every human right for all mankind, irrespective of race, gender, faith, nationality or social status.

In anticipation of that day.

With much gratitude

Shirin Ebadi

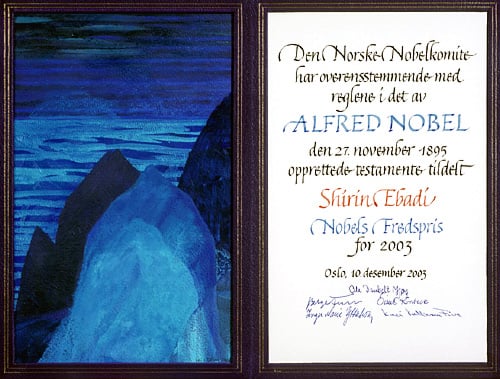

Shirin Ebadi – Nobel diploma

Copyright © The Nobel Foundation 2003

Artist: Kari Elisabeth Dahlmo

Calligrapher: Inger Magnus

Shirin Ebadi – Interview

Shirin Ebadi, 2003 Nobel Peace Prize Laureate, visited Stockholm 22 November 2010. She is in exile in the United Kingdom since June 2009, but she never ceases her work for human rights in Iran.

Shirin Ebadi – Other resources

Links to other sites

Profile: Shirin Ebadi from BBC News

The Struggle for Human Rights in Iran. A conversation with Shirin Ebadi from UC Berkeley

On Shirin Ebadi from the PeaceJam Foundation

On Shirin Ebadi from Nobel Women’s Initiative

Nobels Fredspris 2003 – Pressemelding

English

Norwegian

Den Norske Nobelkomite har bestemt at Nobels fredspris for 2003 skal tildelast Shirin Ebadi for hennar innsats for demokrati og menneskerettar. Ho har særleg engasjert seg i kampen for rettane til kvinner og born.

Som advokat, domar, førelesar, forfattar og aktivist har røysta hennar lydd klår og sterk i hennar land, Iran, og langt ut over heimlandet. Ho har stått fram med fagleg tyngd, stort mot og ho har trassa faren for eigen tryggleik.

Kampen for dei grunnleggjande menneskerettane er hennar fremste arena, og ikkje noko samfunn fortener å kallast sivilisert utan at rettane til kvinner og born blir respekterte. I ei valdeleg tid har ho konsekvent stått for ikkjevald. For henne er det grunnleggjande at den øvste politiske makt i eit samfunn må kvila på demokratiske val. Ho legg vekt på at opplysning og dialog er beste vegen til å endra haldningar og løysa konfliktar.

Ebadi er medveten muslim. Ho ser ingen motsetnad mellom Islam og fundamentale menneskerettar. Og ho legg vekt på at dialogen mellom dei ulike kulturane og religionane i verda må ta utgangspunkt i dei verdiar dei har saman. Det er ei glede for Den Norske Nobelkomite å kunna dela ut fredsprisen til ei kvinne som høyrer den muslimske verda til og som den verda kan vera stolt av – saman med alle som strir for menneskerettar kvar helst i verda dei lever.

I dei siste tiåra har demokrati og menneskerettar vunne sterkare fram i ulike deler av verda. Ved tildelingar av Nobels fredspris har Den Norske Nobelkomite forsøkt å skunda på denne prosessen.

Det er vår von at Irans folk vil kjenna glede ved at ein borgar av deira land for fyrste gong i historia får Nobels Fredspris og vi vonar at prisen vil bli til inspirasjon for dei mange som arbeider for menneskerettar og demokrati i hennar land, i den muslimske verda og i alle land der arbeid for menneskerettar treng inspirasjon og støtte.

Oslo, 10. oktober 2003

Press release

English

Norwegian

The Norwegian Nobel Committee has decided to award the Nobel Peace Prize for 2003 to Shirin Ebadi for her efforts for democracy and human rights. She has focused especially on the struggle for the rights of women and children.

As a lawyer, judge, lecturer, writer and activist, she has spoken out clearly and strongly in her country, Iran, and far beyond its borders. She has stood up as a sound professional, a courageous person, and has never heeded the threats to her own safety.

Her principal arena is the struggle for basic human rights, and no society deserves to be labelled civilized unless the rights of women and children are respected. In an era of violence, she has consistently supported non-violence. It is fundamental to her view that the supreme political power in a community must be built on democratic elections. She favours enlightenment and dialogue as the best path to changing attitudes and resolving conflict.

Ebadi is a conscious Moslem. She sees no conflict between Islam and fundamental human rights. It is important to her that the dialogue between the different cultures and religions of the world should take as its point of departure their shared values. It is a pleasure for the Norwegian Nobel Committee to award the Peace Prize to a woman who is part of the Moslem world, and of whom that world can be proud – along with all who fight for human rights wherever they live.

During recent decades, democracy and human rights have advanced in various parts of the world. By its awards of the Nobel Peace Prize, the Norwegian Nobel Committee has attempted to speed up this process.

We hope that the people of Iran will feel joyous that for the first time in history one of their citizens has been awarded the Nobel Peace Prize, and we hope the Prize will be an inspiration for all those who struggle for human rights and democracy in her country, in the Moslem world, and in all countries where the fight for human rights needs inspiration and support.

Oslo, 10 October 2003