Read or watch the Nobel Prize lecture by R. K. Pachauri, Chairman of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change.

Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change – Speed read

The Intergovernmental Panel of Climate Change (IPCC) was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize, jointly with Al Gore, for their efforts to disseminate greater knowledge about man-made climate change, and to lay the foundations for the measures that are needed to counteract such change.

Full name: Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC)

Native name: Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change

Founded: 1988, New York, NY, USA

Date awarded: 12 October 2007

Global agents for the environment

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) was established by the World Meteorological Organisation and the UN Environment Programme in 1988. The panel documents the scientific basis for climate change by summarising the efforts of thousands of scientists. Its reports form the foundation for international climate policies and have created a broader understanding of the relationship between human activities and global warming. Climate change threatens our conditions of life and can lead to large-scale migrations and greater competition for the earth’s resources. Fighting this threat is therefore crucial for preventing conflict. It is therefore an effective peace strategy to strengthen nations’ abilities to adapt to climate change.

From the announcement speech

The Norwegian Nobel Committee has decided that the Nobel Peace Prize for 2007 is to be shared, in two equal parts, between the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) and Albert Arnold (Al) Gore Jr. for their efforts to build up and disseminate greater knowledge about man-made climate change, and to lay the foundations for the measures that are needed to counteract such change. Extensive climate changes may induce large-scale migration and lead to greater competition for the earth’s resources. There may be increased danger of violent conflicts and wars, within and between states. Ole Danbolt Mjøs, Oslo, 12 October 2007.

Climate changes have different impacts

It is not necessarily those countries that are responsible for the greatest emissions that will suffer most as a result of climate changes. On the contrary, it is the poorest countries that will be hardest hit. The Chairman of the IPCC, Dr. Rajenda K. Pachauri has said that he is concerned about the fact that some countries are disregarding the impact that their emissions are having in other countries. He thinks that the ethical dimensions of this problem are being completely ignored. This has also been expressed previously by Al Gore, who said that: “The climate crisis is not a political issue – it is a moral and spiritual challenge to all of humanity.”

Learn more

Disclaimer: Every effort has been made by the publisher to credit organisations and individuals with regard to the supply of photographs. Please notify the publishers regarding corrections.

Al Gore – Speed read

Al Gore was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize, jointly with the Intergovernmental Panel of Climate Change (IPCC), for his efforts to disseminate greater knowledge about man-made climate change, and to lay the foundations for the measures that are needed to counteract such change.

Full name: Albert Arnold (Al) Gore Jr.

Born: 31 March 1948, Washington, D.C., USA

Date awarded: 12 October 2007

Criticism of Gore

Al Gore and the film An inconvenient truth quickly met criticism. Right-wingers in the US claimed that the film aimed to scare politicians into subsidising green technology in which Gore had invested. Most debate was about claims by climate-change sceptics that the film was full of unscientific propaganda. In the UK, this led to a court case. The judge found that the film’s overall message was in line with climate research, although it did contain some minor factual errors. He held that the film could be shown in UK schools as long as pupils were informed of these errors.

“The world has a fever and we must stop it.”

Al Gore, 11 May 2007

Champion of the environment

Former US Vice President, Al Gore, has long been one of the world’s leading environmentalists. He became aware of the global environmental challenges during his student years, and he was one of the first US politicians to speak of the greenhouse effect. Al Gore has demonstrated a strong commitment to the struggle against man-made climate change through political activity, lectures, films and books. He has raised awareness about the seriousness of the climate threat in many parts of the world. He consistently urges authorities and individuals to act now. His film, An Inconvenient Truth won an Oscar in 2007. By awarding the Nobel Peace Prize to Al Gore, the Nobel Committee is highlighting how the environmental struggle and threats to global security are interlinked.

From the announcement speech

The Norwegian Nobel Committee has decided that the Nobel Peace Prize for 2007 is to be shared, in two equal parts, between the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) and Albert Arnold (Al) Gore Jr. for their efforts to build up and disseminate greater knowledge about man-made climate change, and to lay the foundations for the measures that are needed to counteract such change. Extensive climate changes may induce large-scale migration and lead to greater competition for the earth’s resources. There may be increased danger of violent conflicts and wars, within and between states. Ole Danbolt Mjøs, Oslo, 12 October 2007.

Climate changes have different impacts

It is not necessarily those countries that are responsible for the greatest emissions that will suffer most as a result of climate changes. On the contrary, it is the poorest countries that will be hardest hit. The Chairman of the IPCC, Dr. Rajenda K. Pachauri has said that he is concerned about the fact that some countries are disregarding the impact that their emissions are having in other countries. He thinks that the ethical dimensions of this problem are being completely ignored. This has also been expressed previously by Al Gore, who said that: “The climate crisis is not a political issue – it is a moral and spiritual challenge to all of humanity.”

Learn more

Former Vice President Al Gore is chairman of Current TV, an award winning, independently owned cable and satellite television nonfiction network for young people based on viewer-created content and citizen journalism …

Disclaimer: Every effort has been made by the publisher to credit organisations and individuals with regard to the supply of photographs. Please notify the publishers regarding corrections.

Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change – Documentary

The Lost Forest

“The local people know of nobody in the surrounding communities who have ever been up to the forest”

How would natural habitats develop without human interference? In this documentary we follow an international team of scientists and explorers on an extraordinary mission in Mozambique to reach a forest that no human has set foot in. The team aims to collect data from the forest to help our understanding of how climate change is affecting our planet. But the forest sits atop a mountain, and to reach it, the team must first climb a sheer 100m wall of rock. The scientist’s work is based on research conducted by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change.

Speed read: The risk of climate change

For the third successive year, but for only the sixth time since it was initiated in 1901, the Nobel Peace Prize has been divided equally between an institution and an individual. In awarding the Prize to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), the global body responsible for scientific assessment of climate change, and Albert Arnold (Al) Gore, the phenomenon’s most renowned campaigner, the Norwegian Nobel Committee are highlighting the link they see between the risk of accelerating climate change and the risk of violent conflict and wars.

The IPCC was established by the United Nations Environmental Programme (UNEP) and the World Meteorological Organization (WMO) in 1988 to provide policymakers with neutral summaries of the latest information related to human-induced (or anthropogenic) climate change. Run from offices in Geneva, but open to any of the nearly 200 member states belonging to the UN or WMO, the IPCC functions through its working groups. There are currently 3 working groups, focusing on the science, impact and mitigation of climate change, and one task force charged with developing greenhouse gas inventories. The findings of the IPCC are presented as ‘Assessment reports’, synthesizing the views of the working groups, which are produced approximately every 5 years. The fourth and next report is due at the end of 2007.

The working groups have already published their individual contributions to the forthcoming fourth report. A quote from the Science Working Group’s report states “Most of the observed increase in global average temperatures since the mid-20th century is very likely due to the observed increase in anthropogenic greenhouse gas concentrations”. A quote from Working Group II, which looks at impact, states “Much more evidence has accumulated over the past five years to indicate that changes in many physical and biological systems are linked to anthropogenic warming”. They go on to say that “Unmitigated climate change would, in the long term, be likely to exceed the capacity of natural, managed and human systems to adapt”.

Al Gore is the leading public advocate of the need to take immediate action to reduce anthropogenic climate change. His campaigning takes many forms, including the Academy Award-winning film An Inconvenient Truth and a book of the same name. He is also the founder and Chairman of the Alliance for Climate Change, an organization dedicated to persuading people of the urgency of responding to what it calls the ‘climate crisis’.

Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change – Photo gallery

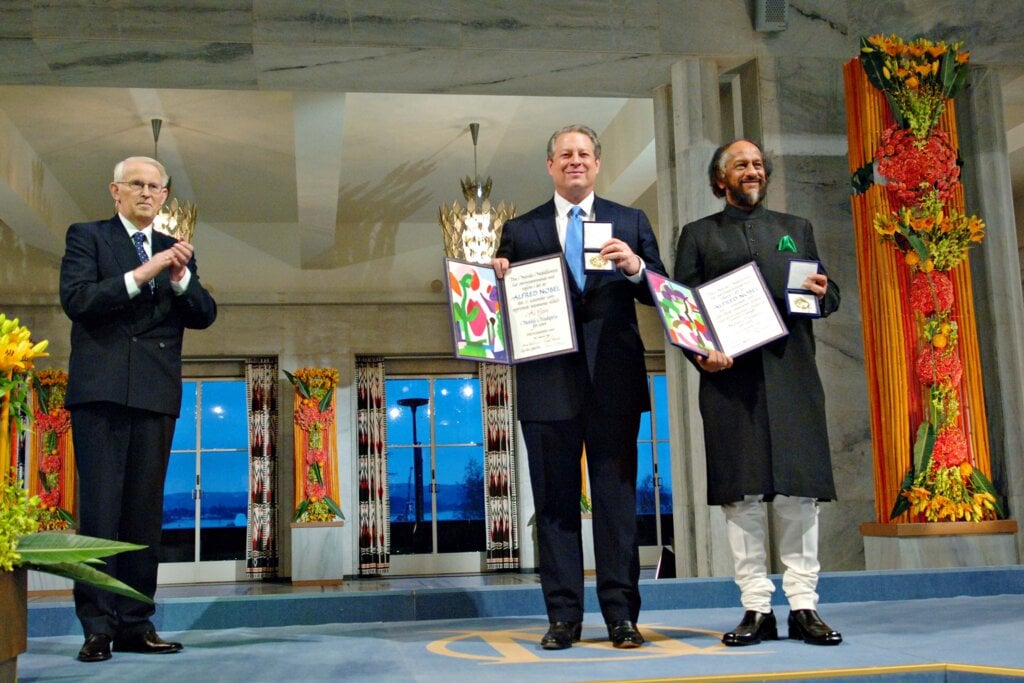

Nobel Peace Prize Laureates Al Gore (left) and

Rajendra K. Pachauri, Chairman of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) with their Nobel Peace

Prize Medals and Diplomas at the Award Ceremony in Oslo, Norway, 10 December 2007.

Copyright © The Norwegian Nobel Institute 2007

Photo: Ken Opprann

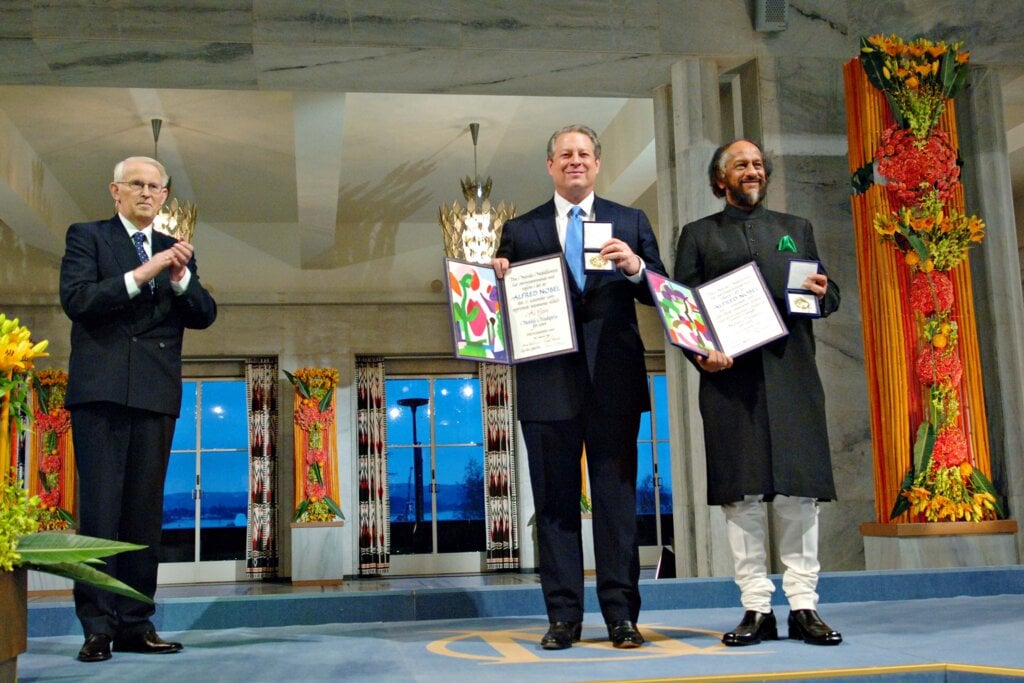

Nobel Peace Prize laureates Al Gore (middle) and Rajendra K. Pachauri, Chairman of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) with their Nobel Peace Prize medals and diplomas at the award ceremony in Oslo, Norway, 10 December 2007. To the far left is Ole Danbolt Mjøs, Chairman of the Norwegian Nobel Committee.

Copyright © The Norwegian Nobel Institute 2007. Photo: Ken Opprann

Rajendra K. Pachauri (representing the IPCC) and Al Gore listen to the introductory speech during the 2007 Nobel Peace Prize Award Ceremony.

Copyright © The Norwegian Nobel Institute 2007

Photo: Ken Opprann

The 2007 Nobel Peace Prize Laureates and their spouses with the Norwegian Royal Family at the Royal Palace in Oslo, Norway (from left to right): Their Royal Highnesses Crown Prince Haakon and Crown Princess Mette-Marit of Norway, Rajendra K. Pachauri, Saroj Pachauri, Tipper Gore, Al Gore, and Their Majesties King Harald V and Queen Sonja of Norway.

Copyright © The Norwegian Nobel Institute 2007

Photo: Ken Opprann

Al Gore and Rajendra K. Pachauri among the audience at the Nobel Peace Prize Concert. Artists from all over the world have gathered at the Oslo Spektrum in Norway to honour the 2007 Nobel Peace Prize Laureates and help spread a message of peace.

Copyright © The Norwegian Nobel Institute 2007

Photo: Ken Opprann

Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change – Prize presentation

Al Gore – Nobel Lecture

Al Gore delivered his Nobel Lecture on 10 December 2007 at the Oslo City Hall, Norway. He was introduced by Professor Ole Danbolt Mjøs, Chairman of the Norwegian Nobel Committee.

English

Norwegian

Nobel Lecture, Oslo, 10 December 2007.

Your Majesties, Your Royal Highnesses, Honorable members of the Norwegian Nobel Committee, Excellencies, Ladies and gentlemen.

I have a purpose here today. It is a purpose I have tried to serve for many years. I have prayed that God would show me a way to accomplish it.

Sometimes, without warning, the future knocks on our door with a precious and painful vision of what might be. One hundred and nineteen years ago, a wealthy inventor read his own obituary, mistakenly published years before his death. Wrongly believing the inventor had just died, a newspaper printed a harsh judgment of his life’s work, unfairly labeling him “The Merchant of Death” because of his invention – dynamite. Shaken by this condemnation, t he inventor made a fateful choice to serve the cause of peace.

Seven years later, Alfred Nobel created this prize and the others that bear his name.

Seven years ago tomorrow, I read my own political obituary in a judgment that seemed to me harsh and mistaken – if not premature. But that unwelcome verdict also brought a precious if painful gift: an opportunity to search for fresh new ways to serve my purpose.

Unexpectedly, that quest has brought me here. Even though I fear my words cannot match this moment, I pray what I am feeling in my heart will be communicated clearly enough that those who hear me will say, “We must act.”

The distinguished scientists with whom it is the greatest honor of my life to share this award have laid before us a choice between two different futures – a choice that to my ears echoes the words of an ancient prophet: “Life or death, blessings or curses. Therefore, choose life, that both thou and thy seed may live.”

We, the human species, are confronting a planetary emergency – a threat to the survival of our civilization that is gathering ominous and destructive potential even as we gather here. But there is hopeful news as well: we have the ability to solve this crisis and avoid the worst – though not all – of its consequences, if we act boldly, decisively and quickly.

However, despite a growing number of honorable exceptions, too many of the world’s leaders are still best described in the words Winston Churchill applied to those who ignored Adolf Hitler’s threat: “They go on in strange paradox, decided only to be undecided, resolved to be irresolute, adamant for drift, solid for fluidity, all powerful to be impotent.”

So today, we dumped another 70 million tons of global-warming pollution into the thin shell of atmosphere surrounding our planet, as if it were an open sewer. And tomorrow, we will dump a slightly larger amount, with the cumulative concentrations now trapping more and more heat from the sun.

As a result, the earth has a fever. And the fever is rising. The experts have told us it is not a passing affliction that will heal by itself. We asked for a second opinion. And a third. And a fourth. And the consistent conclusion, restated with increasing alarm, is that something basic is wrong.

We are what is wrong, and we must make it right.

Last September 21, as the Northern Hemisphere tilted away from the sun, scientists reported with unprecedented distress that the North Polar ice cap is “falling off a cliff.” One study estimated that it could be completely gone during summer in less than 22 years. Another new study, to be presented by U.S. Navy researchers later this week, warns it could happen in as little as 7 years.

Seven years from now.

In the last few months, it has been harder and harder to misinterpret the signs that our world is spinning out of kilter. Major cities in North and South America, Asia and Australia are nearly out of water due to massive droughts and melting glaciers. Desperate farmers are losing their livelihoods. Peoples in the frozen Arctic and on low-lying Pacific islands are planning evacuations of places they have long called home. Unprecedented wildfires have forced a half million people from their homes in one country and caused a national emergency that almost brought down the government in another. Climate refugees have migrated into areas already inhabited by people with different cultures, religions, and traditions, increasing the potential for conflict. Stronger storms in the Pacific and Atlantic have threatened whole cities. Millions have been displaced by massive flooding in South Asia, Mexico, and 18 countries in Africa. As temperature extremes have increased, tens of thousands have lost their lives. We are recklessly burning and clearing our forests and driving more and more species into extinction. The very web of life on which we depend is being ripped and frayed.

We never intended to cause all this destruction, just as Alfred Nobel never intended that dynamite be used for waging war. He had hoped his invention would promote human progress. We shared that same worthy goal when we began burning massive quantities of coal, then oil and methane.

Even in Nobel’s time, there were a few warnings of the likely consequences. One of the very first winners of the Prize in chemistry worried that, “We are evaporating our coal mines into the air.” After performing 10,000 equations by hand, Svante Arrhenius calculated that the earth’s average temperature would increase by many degrees if we doubled the amount of CO2 in the atmosphere.

Seventy years later, my teacher, Roger Revelle, and his colleague, Dave Keeling, began to precisely document the increasing CO2 levels day by day.

But unlike most other forms of pollution, CO2 is invisible, tasteless, and odorless – which has helped keep the truth about what it is doing to our climate out of sight and out of mind. Moreover, the catastrophe now threatening us is unprecedented – and we often confuse the unprecedented with the improbable.

We also find it hard to imagine making the massive changes that are now necessary to solve the crisis. And when large truths are genuinely inconvenient, whole societies can, at least for a time, ignore them. Yet as George Orwell reminds us: “Sooner or later a false belief bumps up against solid reality, usually on a battlefield.”

In the years since this prize was first awarded, the entire relationship between humankind and the earth has been radically transformed. And still, we have remained largely oblivious to the impact of our cumulative actions.

Indeed, without realizing it, we have begun to wage war on the earth itself. Now, we and the earth’s climate are locked in a relationship familiar to war planners: “Mutually assured destruction.”

More than two decades ago, scientists calculated that nuclear war could throw so much debris and smoke into the air that it would block life-giving sunlight from our atmosphere, causing a “nuclear winter.” Their eloquent warnings here in Oslo helped galvanize the world’s resolve to halt the nuclear arms race.

Now science is warning us that if we do not quickly reduce the global warming pollution that is trapping so much of the heat our planet normally radiates back out of the atmosphere, we are in danger of creating a permanent “carbon summer.”

As the American poet Robert Frost wrote, “Some say the world will end in fire; some say in ice.” Either, he notes, “would suffice.”

But neither need be our fate. It is time to make peace with the planet.

We must quickly mobilize our civilization with the urgency and resolve that has previously been seen only when nations mobilized for war. These prior struggles for survival were won when leaders found words at the 11th hour that released a mighty surge of courage, hope and readiness to sacrifice for a protracted and mortal challenge.

These were not comforting and misleading assurances that the threat was not real or imminent; that it would affect others but not ourselves; that ordinary life might be lived even in the presence of extraordinary threat; that Providence could be trusted to do for us what we would not do for ourselves.

No, these were calls to come to the defense of the common future. They were calls upon the courage, generosity and strength of entire peoples, citizens of every class and condition who were ready to stand against the threat once asked to do so. Our enemies in those times calculated that free people would not rise to the challenge; they were, of course, catastrophically wrong.

Now comes the threat of climate crisis – a threat that is real, rising, imminent, and universal. Once again, it is the 11th hour. The penalties for ignoring this challenge are immense and growing, and at some near point would be unsustainable and unrecoverable. For now we still have the power to choose our fate, and the remaining question is only this: Have we the will to act vigorously and in time, or will we remain imprisoned by a dangerous illusion?

Mahatma Gandhi awakened the largest democracy on earth and forged a shared resolve with what he called “Satyagraha” – or “truth force.”

In every land, the truth – once known – has the power to set us free.

Truth also has the power to unite us and bridge the distance between “me” and “we,” creating the basis for common effort and shared responsibility.

There is an African proverb that says, “If you want to go quickly, go alone. If you want to go far, go together.” We need to go far, quickly.

We must abandon the conceit that individual, isolated, private actions are the answer. They can and do help. But they will not take us far enough without collective action. At the same time, we must ensure that in mobilizing globally, we do not invite the establishment of ideological conformity and a new lock-step “ism.”

That means adopting principles, values, laws, and treaties that release creativity and initiative at every level of society in multifold responses originating concurrently and spontaneously.

This new consciousness requires expanding the possibilities inherent in all humanity. The innovators who will devise a new way to harness the sun’s energy for pennies or invent an engine that’s carbon negative may live in Lagos or Mumbai or Montevideo. We must ensure that entrepreneurs and inventors everywhere on the globe have the chance to change the world.

When we unite for a moral purpose that is manifestly good and true, the spiritual energy unleashed can transform us. The generation that defeated fascism throughout the world in the 1940s found, in rising to meet their awesome challenge, that they had gained the moral authority and long-term vision to launch the Marshall Plan, the United Nations, and a new level of global cooperation and foresight that unified Europe and facilitated the emergence of democracy and prosperity in Germany, Japan, Italy and much of the world. One of their visionary leaders said, “It is time we steered by the stars and not by the lights of every passing ship.”

In the last year of that war, you gave the Peace Prize to a man from my hometown of 2000 people, Carthage, Tennessee. Cordell Hull was described by Franklin Roosevelt as the “Father of the United Nations.” He was an inspiration and hero to my own father, who followed Hull in the Congress and the U.S. Senate and in his commitment to world peace and global cooperation.

My parents spoke often of Hull, always in tones of reverence and admiration. Eight weeks ago, when you announced this prize, the deepest emotion I felt was when I saw the headline in my hometown paper that simply noted I had won the same prize that Cordell Hull had won. I n that moment, I knew what my father and mother would have felt were they alive.

Just as Hull’s generation found moral authority in rising to solve the world crisis caused by fascism, so too can we find our greatest opportunity in rising to solve the climate crisis. In the Kanji characters used in both Chinese and Japanese, “crisis” is written with two symbols, the first meaning “danger,” the second “opportunity.” By facing and removing the danger of the climate crisis, we have the opportunity to gain the moral authority and vision to vastly increase our own capacity to solve other crises that have been too long ignored.

We must understand the connections between the climate crisis and the afflictions of poverty, hunger, HIV-Aids and other pandemics. As these problems are linked, so too must be their solutions. We must begin by making the common rescue of the global environment the central organizing principle of the world community.

Fifteen years ago, I made that case at the “Earth Summit” in Rio de Janeiro. Ten years ago, I presented it in Kyoto. This week, I will urge the delegates in Bali to adopt a bold mandate for a treaty that establishes a universal global cap on emissions and uses the market in emissions trading to efficiently allocate resources to the most effective opportunities for speedy reductions.

This treaty should be ratified and brought into effect everywhere in the world by the beginning of 2010 – two years sooner than presently contemplated. The pace of our response must be accelerated to match the accelerating pace of the crisis itself.

Heads of state should meet early next year to review what was accomplished in Bali and take personal responsibility for addressing this crisis. It is not unreasonable to ask, given the gravity of our circumstances, that these heads of state meet every three months until the treaty is completed.

We also need a moratorium on the construction of any new generating facility that burns coal without the capacity to safely trap and store carbon dioxide.

And most important of all, we need to put a price on carbon – with a CO2 tax that is then rebated back to the people, progressively, according to the laws of each nation, in ways that shift the burden of taxation from employment to pollution. This is by far the most effective and simplest way to accelerate solutions to this crisis.

The world needs an alliance – especially of those nations that weigh heaviest in the scales where earth is in the balance. I salute Europe and Japan for the steps they’ve taken in recent years to meet the challenge, and the new government in Australia, which has made solving the climate crisis its first priority.

But the outcome will be decisively influenced by two nations that are now failing to do enough: the United States and China. While India is also growing fast in importance, it should be absolutely clear that it is the two largest CO2 emitters – most of all, my own country – that will need to make the boldest moves, or stand accountable before history for their failure to act.

Both countries should stop using the other’s behavior as an excuse for stalemate and instead develop an agenda for mutual survival in a shared global environment.

These are the last few years of decision, but they can be the first years of a bright and hopeful future if we do what we must. No one should believe a solution will be found without effort, without cost, without change. Let us acknowledge that if we wish to redeem squandered time and speak again with moral authority, then these are the hard truths:

The way ahead is difficult. The outer boundary of what we currently believe is feasible is still far short of what we actually must do. Moreover, between here and there, across the unknown, falls the shadow.

That is just another way of saying that we have to expand the boundaries of what is possible. In the words of the Spanish poet, Antonio Machado, “Pathwalker, there is no path. You must make the path as you walk.”

We are standing at the most fateful fork in that path. So I want to end as I began, with a vision of two futures – each a palpable possibility – and with a prayer that we will see with vivid clarity the necessity of choosing between those two futures, and the urgency of making the right choice now.

The great Norwegian playwright, Henrik Ibsen, wrote, “One of these days, the younger generation will come knocking at my door.”

The future is knocking at our door right now. Make no mistake, the next generation will ask us one of two questions. Either they will ask: “What were you thinking; why didn’t you act? “

Or they will ask instead: “How did you find the moral courage to rise and successfully resolve a crisis that so many said was impossible to solve?”

We have everything we need to get started, save perhaps political will, but political will is a renewable resource.

So let us renew it, and say together: “We have a purpose. We are many. For this purpose we will rise, and we will act.”

Copyright © The Nobel Foundation 2007

Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change – Nobel Lecture

R. K. Pachauri, Chairman of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) delivered his Nobel Lecture on 10 December 2007 at the Oslo City Hall, Norway. He was introduced by Professor Ole Danbolt Mjøs, Chairman of the Norwegian Nobel Committee.

English

Norwegian

Nobel Lecture by R. K. Pachauri, Chairman of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), Oslo, 10 December 2007.

Your Majesties, Your Royal Highnesses, Honourable Members of the Norwegian Nobel Committee, Excellencies, My Colleagues from the IPCC, Distinguished Ladies & Gentlemen.

As Chair of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) I am deeply privileged to present this lecture on behalf of the Panel on the occasion of the Nobel Peace Prize being awarded to the IPCC jointly with Mr Al Gore. While doing so, I pay tribute to the thousands of experts and scientists who have contributed to the work of the Panel over almost two decades of exciting evolution and service to humanity. On this occasion I also salute the leadership provided by my predecessors Prof. Bert Bolin and Dr Robert Watson. One of the major strengths of the IPCC is the procedures and practices that it has established over the years, and the credit for these go primarily to Prof. Bolin for their introduction and to Dr Watson for building on the efforts of the former most admirably. I had requested Professor Bolin to receive this award on behalf of the IPCC, but ill health prevents him from being with us physically. I convey my best wishes to him. My gratitude also to UNEP and WMO for their support, represented here today by Dr. Mostapha Tolba, one of the founders of the IPCC and Dr. Michel Jarraud respectively. I express my deep thanks also to the Vice-Chairs of the IPCC, Professors Izrael, Odingo and Munasinghe for their contributions to the IPCC over the years.

The Fourth Assessment Report of the IPCC has had a major impact in creating public awareness on various aspects of climate change, and the three Working Group reports as part of this assessment represent a major advance in scientific knowledge, for which I must acknowledge the remarkable leadership of the Co-Chairs of the three Working Groups, Dr Susan Solomon, Dr Qin Dahe for Working Group I; Dr Martin Parry and Dr Osvaldo Canziani for Working Group II; and Dr Bert Metz and Dr Ogunlade Davidson for Working Group III respectively. The Synthesis Report, which distills and integrates the major findings from these three reports has also benefited enormously from their valuable inputs.

The IPCC produces key scientific material that is of the highest relevance to policymaking, and is agreed word-by-word by all governments, from the most skeptical to the most confident. This difficult process is made possible by the tremendous strength of the underlying scientific and technical material included in the IPCC reports.

The Panel was established in 1988 through a resolution of the UN General Assembly. One of its clauses was significant in having stated, “Noting with concern that the emerging evidence indicates that continued growth in atmospheric concentrations of “greenhouse” gases could produce global warming with an eventual rise in sea levels, the effects of which could be disastrous for mankind if timely steps are not taken at all levels”. This means that almost two decades ago the UN was acutely conscious of the possibility of disaster consequent on climate change through increases in sea levels. Today we know much more, which provides greater substance to that concern.

This award being given to the IPCC, we believe goes fundamentally beyond a concern for the impacts of climate change on peace. Mr Berge Furre expressed eloquently during the Nobel Banquet on 10 December 2004 an important tenet when he said “We honour the earth; for bringing forth flowers and food – and trees … The Norwegian Nobel Committee is committed to the protection of the earth. This commitment is our vision – deeply felt and connected to human rights and peace”. Honouring the IPCC through the grant of the Nobel Peace Prize in 2007 in essence can be seen as a clarion call for the protection of the earth as it faces the widespread impacts of climate change. The choice of the Panel for this signal honour is, in our view, an acknowledgement of three important realities, which can be summed up as:

- The power and promise of collective scientific endeavour, which, as demonstrated by the IPCC, can reach across national boundaries and political differences in the pursuit of objectives defining the larger good of human society.

- The importance of the role of knowledge in shaping public policy and guiding global affairs for the sustainable development of human society.

- An acknowledgement of the threats to stability and human security inherent in the impacts of a changing climate and, therefore, the need for developing an effective rationale for timely and adequate action to avoid such threats in the future.

These three realities encircle an important truth that must guide global action involving the entire human race in the future. Coming as I do from India, a land which gave birth to civilization in ancient times and where much of the earlier tradition and wisdom guides actions even in modern times, the philosophy of “Vasudhaiva Kutumbakam”, which means the whole universe is one family, must dominate global efforts to protect the global commons. This principle is crucial to the maintenance of peace and order today as it would be increasingly in the years ahead, and as the well-known columnist and author Thomas Friedman has highlighted in his book “The World is Flat”.

Neglect in protecting our heritage of natural resources could prove extremely harmful for the human race and for all species that share common space on planet earth. Indeed, there are many lessons in human history which provide adequate warning about the chaos and destruction that could take place if we remain guilty of myopic indifference to the progressive erosion and decline of nature’s resources. Much has been written, for instance, about the Maya civilization, which flourished during 250–950 AD, but collapsed largely as a result of serious and prolonged drought. Even earlier, some 4000 years ago a number of well-known Bronze Age cultures also crumbled extending from the Mediterranean to the Indus Valley, including the civilizations, which had blossomed in Mesopotamia. More recent examples of societies that collapsed or faced chaos on account of depletion or degradation of natural resources include the Khmer Empire in South East Asia, Eastern Island, and several others. Changes in climate have historically determined periods of peace as well as conflict. The recent work of David Zhang has, in fact, highlighted the link between temperature fluctuations, reduced agricultural production, and the frequency of warfare in Eastern China over the last millennium. Further, in recent years several groups have studied the link between climate and security. These have raised the threat of dramatic population migration, conflict, and war over water and other resources as well as a realignment of power among nations. Some also highlight the possibility of rising tensions between rich and poor nations, health problems caused particularly by water shortages, and crop failures as well as concerns over nuclear proliferation.

One of the most significant aspects of the impacts of climate change, which has unfortunately not received adequate attention from scholars in the social sciences, relates to the equity implications of changes that are occurring and are likely to occur in the future. In general, the impacts of climate change on some of the poorest and the most vulnerable communities in the world could prove extremely unsettling. And, given the inadequacy of capacity, economic strength, and institutional capabilities characterizing some of these communities, they would remain extremely vulnerable to the impacts of climate change and may, therefore, actually see a decline in their economic condition, with a loss of livelihoods and opportunities to maintain even subsistence levels of existence. Since the IPCC by its very nature is an organization that does not provide assessments, which are policy prescriptive, it has not provided any directions on how conflicts inherent in the social implications of the impacts of climate change could be avoided or contained. Nevertheless, the Fourth Assessment Report provides scientific findings that other scholars can study and arrive at some conclusions on in relation to peace and security. Several parts of our reports have much information and knowledge that would be of considerable value for individual researchers and think tanks dealing with security issues as well as governments that necessarily are concerned with some of these matters. It would be particularly relevant to conduct in-depth analysis of risks to security among the most vulnerable sectors and communities impacted by climate change across the globe.

Peace can be defined as security and the secure access to resources that are essential for living. A disruption in such access could prove disruptive of peace. In this regard, climate change will have several implications, as numerous adverse impacts are expected for some populations in terms of:

– access to clean water,

– access to sufficient food,

– stable health conditions,

– ecosystem resources,

– security of settlements.

Climate change is expected to exacerbate current stresses on water resources. On a regional scale, mountain snowpack, glaciers, and small ice caps play a crucial role in fresh water availability. Widespread mass losses from glaciers and reductions in snow cover over recent decades are projected to accelerate throughout the 21st century, reducing water availability, hydropower potential, and the changing seasonality of flows in regions supplied by meltwater from major mountain ranges (e.g. Hindu-Kush, Himalaya, Andes), where more than one-sixth of the world’s population currently lives. There is also high confidence that many semi-arid areas (e.g. the Mediterranean Basin, western United States, southern Africa, and northeastern Brazil) will suffer a decrease in water resources due to climate change. In Africa by 2020, between 75 and 250 million people are projected to be exposed to increased water stress due to climate change.

Climate change could further adversely affect food security and exacerbate malnutrition at low latitudes, especially in seasonally dry and tropical regions, where crop productivity is projected to decrease for even small local temperature increases (1–2 °C). By 2020, in some African countries, yields from rain-fed agriculture could be reduced by up to 50%. Agricultural production, including access to food, in many African countries is projected to be severely compromised.

The health status of millions of people is projected to be affected through, for example, increases in malnutrition; increased deaths, diseases, and injury due to extreme weather events; increased burden of diarrhoeal diseases; increased frequency of cardio-respiratory diseases due to higher concentrations of ground-level ozone in urban areas related to climate change; and the altered spatial distribution of some infectious diseases.

Climate change is likely to lead to some irreversible impacts on biodiversity. There is medium confidence that approximately 20%–30% of species assessed so far are likely to be at increased risk of extinction if increases in global average warming exceed 1.5–2.5 ºC, relative to 1980–99. As global average temperature exceeds about 3.5 ºC, model projections suggest significant extinctions (40%–70% of species assessed) around the globe. These changes, if they were to occur would have serious effects on the sustainability of several ecosystems and the services they provide to human society.

As far as security of human settlements is concerned, vulnerabilities to climate change are generally greater in certain high-risk locations, particularly coastal and riverine areas, and areas whose economies are closely linked with climate-sensitive resources. Where extreme weather events become more intense or more frequent with climate change, the economic and social costs of those events will increase.

Some regions are likely to be especially affected by climate change.

– The Arctic, because of the impacts of high rates of projected warming on natural systems and human communities,

– Africa, because of low adaptive capacity and projected climate change impacts,

– Small islands, where there is high exposure of population and infrastructure to projected climate change impacts

– Asian and African megadeltas, due to large populations and high exposure to sea level rise, storm surges, and river flooding.

The IPCC Fourth Assessment Report concludes that non-climate stresses can increase vulnerability to climate change by reducing resilience and can also reduce adaptive capacity because of resource deployment towards competing needs. Vulnerable regions face multiple stresses that affect their exposure and sensitivity to various impacts as well as their capacity to adapt. These stresses arise from, for example, current climate hazards, poverty, and unequal access to resources, food insecurity, trends in economic globalization, conflict, and incidence of diseases such as HIV/AIDS.

Within other areas, even those with high incomes, some people (such as the poor, young children, and the elderly) can be particularly at risk.

Migration and movement of people is a particularly critical source of potential conflict. Migration, usually temporary and often from rural to urban areas, is a common response to calamities such as floods and famines. But as in the case of vulnerability to the impacts of climate change, where multiple stresses could be at work on account of a diversity of causes and conditions, so also in the case of migration, individuals may have multiple motivations and they could be displaced by multiple factors.

Another issue of extreme concern is the finding that anthropogenic factors could lead to some impacts that are abrupt or irreversible, depending on the rate and magnitude of climate change. For instance, partial loss of ice sheets on polar land could imply metres of sea level rise, major changes in coastlines, and inundation of low-lying areas, with greatest effects in river deltas and low-lying islands.

Global average warming above about 4.5 ºC relative to 1980–99 (about

5 ºC above pre-industrial) would imply:

– Projected decreases of precipitation by up to 20% in many dry tropical and subtropical areas.

– Expected mass loss of Greenland’s ice if sustained over many centuries (based on all current global climate system models assessed) leading to sea level rise up to 4 metres and flooding of shorelines on every continent.

The implications of these changes, if they were to occur would be grave and disastrous. However, it is within the reach of human society to meet these threats. The impacts of climate change can be limited by suitable adaptation measures and stringent mitigation of greenhouse gas emissions.

Societies have a long record of adapting to the impacts of weather and climate. But climate change poses novel risks often outside the range of experience, such as impacts related to drought, heat waves, accelerated glacier retreat, and hurricane intensity. These impacts will require adaptive responses such as investments in storm protection and water supply infrastructure, as well as community health services. Adaptation measures essential to reduce such vulnerability, are seldom undertaken in response to climate change alone but can be integrated within, for example, water resource management, coastal defence, and risk-reduction strategies. The global community needs to coordinate a far more proactive effort towards implementing adaptation measures in the most vulnerable communities and systems in the world.

Adaptation is essential to address the impacts resulting from the warming which is already unavoidable due to past emissions. But, adaptation alone is not expected to cope with all the projected effects of climate change, and especially not in the long run as most impacts increase in magnitude.

There is substantial potential for the mitigation of global greenhouse gas emissions over the coming decades that could offset the projected growth of global emissions or reduce emissions below current levels. There are multiple drivers for actions that reduce emissions of greenhouse gases, and they can produce multiple benefits at the local level in terms of economic development and poverty alleviation, employment, energy security, and local environmental protection.

The Fourth Assessment Report has assessed the costs of mitigation in the coming decades for a number of scenarios of stabilisation of the concentration of these gases and associated average global temperature increases at equilibrium. A stabilisation level of 445–590 ppm of CO2 equivalent, which corresponds to a global average temperature increase above pre-industrial at equilibrium (using best estimate climate sensitivity) of around 2.0–2.4 ºC would lead to a reduction in average annual GDP growth rate of less than 0.12% up to 2030 and beyond up to 2050. Essentially, the range of global GDP reduction with the least-cost trajectory assessed for this level of stabilisation would be less than 3% in 2030 and less than 5.5% in 2050. Some important characteristics of this stabilisation scenario need careful consideration:

– For a CO2-equivalent concentration at stabilization of 445–490 ppm, CO2 emissions would need to peak during the period 2000–15 and decline thereafter. We, therefore, have a short window of time to bring about a reduction in global emissions if we wish to limit temperature increase to around 2 oC at equilibrium.

– Even with this ambitious level of stabilisation the global average sea level rise above pre-industrial at equilibrium from thermal expansion only would lie between 0.4–1.4 metres. This would have serious implications for several regions and locations in the world.

A rational approach to management of risk would require that human society evaluates the impacts of climate change inherent in a business-as-usual scenario and the quantifiable costs as well as unquantifiable damages associated with it, against the cost of action. With such an approach the overwhelming result would be in favour of major efforts at mitigation. The impacts of climate change even with current levels of concentration of greenhouse gases would be serious enough to justify stringent mitigation efforts. If the concentration of all greenhouse gases and aerosols had been kept constant at year 2000 levels, a further warming of about 0.1 ºC per decade would be expected. Subsequent temperature projections depend on specific emission scenarios. Those systems and communities, which are vulnerable, may suffer considerably with even small changes in the climate at the margin.

Science tells us not only that the climate system is changing, but also that further warming and sea level rise is in store even if greenhouse gases were to be stabilized today. That is a consequence of the basic physics of the system. Social factors also contribute to our future, including the ‘lock-in’ due, for example, to today’s power plants, transportation systems, and buildings, and their likely continuing emissions even as cleaner future infrastructure comes on line. So the challenge before us is not only a large one, it is also one in which every year of delay implies a commitment to greater climate change in the future.

It would be relevant to recall the words of President Gayoom of the Maldives at the Forty Second Session of the UN General Assembly on the 19 October 1987:

“As for my own country, the Maldives, a mean sea level rise of 2 metres would suffice to virtually submerge the entire country of 1,190 small islands, most of which barely rise

2 metres above mean sea level. That would be the death of a nation. With a mere 1 metre rise also, a storm surge would be catastrophic, and possibly fatal to the nation.”

On 22 September 1997, at the opening of the thirteenth session of the IPCC at Male, the capital of the Maldives, President Gayoom reminded us of the threat to his country when he said, “Ten years ago, in April 1987, this very spot where we are gathered now, was under two feet of water, as unusually high waves inundated one third of Male, as well as the Male International Airport and several other islands of our archipelago.” Hazards from the impacts of climate change are, therefore, a reality today in some parts of the world, and we cannot hide under global averages and the ability of affluent societies to deal with climate-related threats as opposed to the condition of vulnerable communities in poor regions of the globe.

The successive assessment reports published by the IPCC since 1990 demonstrate the progress of scientific knowledge about climate change and its consequences. This progress has been made possible by the combined strength of growing evidence of the observations of changes in climate, dedicated work from the scientific community, and improved efforts in communication of science. We have now more scientific evidence of the reality of climate change and its human contribution. As stated in the Fourth Assessment Report, “warming of the climate system is unequivocal”, and “most of the global average warming over the past 50 years is very likely due to anthropogenic greenhouse gases increases”.

Further progress in scientific assessment needs however to be achieved in order to support strong and adequate responses to the threats of climate change, including adaptation and mitigation policies.

There is also notable lack of geographic data and literature on observed changes, with marked scarcity in developing countries. Future changes in the Greenland and Antarctic ice sheet mass are another major source of uncertainty that could increase sea level rise projections. The need for further scientific input calls for continued trust and cooperation from policymakers and society at large to support the work needed for scientific progress.

How climate change will affect peace is for others to determine, but we have provided scientific assessment of what could become a basis for conflict. When Mr. Willy Brandt spoke at the acceptance of the Nobel Peace Prize in 1971, he said, “… we shall have to know more about the origins of conflicts. … As I see it, next to reasonable politics, learning is in our world the true credible alternative to force.”

The thirteenth Conference of the Parties to the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change is being held in Bali right now. The world’s attention is riveted on that meeting and hopes are alive that unlike the sterile outcome of previous sessions in recent years, this one will provide some positive results. The work of the IPCC has helped the world to learn more on all aspects of climate change, and the Nobel Peace Prize Committee has acknowledged this fact. The question is whether the participants in Bali will support what Willy Brandt referred to as “reasonable politics”. Will those responsible for decisions in the field of climate change at the global level listen to the voice of science and knowledge, which is now loud and clear? If they do so at Bali and beyond then all my colleagues in the IPCC and those thousands toiling for the cause of science would feel doubly honoured at the privilege I am receiving today on their behalf.

Thank you!

Al Gore – Prize presentation

Watch a video clip of the 2007 Nobel Peace Prize Laureate, Al Gore, receiving his Nobel Prize medal and diploma during the Nobel Peace Prize Award Ceremony at the Oslo City Hall in Norway, 10 December 2007.

Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change – Nobel Lecture

English

Norwegian

Nobelforedrag av R. K. Pachauri, leder av Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), Oslo, 10. desember, 2007.

Deres Majesteter, Deres Kongelige Høyheter, ærede medlemmer av den norske Nobelkomiteen, Eksellenser, mine kolleger fra IPCC, Mine damer og herrer.

Som leder av FNs klimapanel (IPCC), er det en stor ære for meg å få lov til å holde dette foredraget på vegne av Panelet i forbindelse med overrekkelsen av Nobels fredspris til IPCC sammen med Al Gore. I den forbindelse vil jeg hylle de flere tusen eksperter og vitenskapsmenn som har bidratt til Panelets arbeid i løpet av nesten tjue års spennende utvikling i menneskehetens tjeneste. Jeg benytter også anledningen til å hylle det lederskapet som ble utøvet av mine to forgjengere, Prof. Bert Bolin og Dr Robert Watson. En av IPCCs sterkeste sider er de prosedyrer og den praksis som er blitt etablert gjennom årenes løp, og æren for å ha innført disse går først og fremst til Prof. Bolin, mens Dr Watson på sin side på en beundringsverdig måte greide å bygge videre på den innsatsen hans forgjenger hadde lagt ned. Min takknemlighet går også til UNEP og WMO, som er representert her i dag ved. Dr. Mostapha Tolba og Dr. Michel Jarraud, for deres støtte. IPCCs fjerde hovedrapport fikk stor innvirkning ved at den skapte en offentlig bevissthet rundt de ulike sidene ved klimaendringene, og de tre arbeidsgruppenes delrapporter, som inngikk i hovedrapporten, representerer et stort fremskritt når det gjelder vitenskapelig kunnskap, og her må jeg berømme lederne av de tre arbeidsgruppene, henholdsvis Dr Susan Solomon, Dr Qin Dahe for arbeidsgruppe I, Dr Martin Parry og Dr Osvaldo Canziani for arbeidsgruppe II og Dr Bert Metz og Dr Ogunlade Davidson for arbeidsgruppe III, som alle har utvist fremragende lederskap. Synteserapporten, som trekker ut og integrerer hovedfunnene i disse tre delrapportene, har også dratt stor nytte av deres verdifulle innspill.

IPCC produserer viktig vitenskapelig materiale som er uhyre relevant i forhold til politikkutforming, og samtlige regjeringer, fra de mest skeptiske til de mest tillitsfulle, har sluttet seg til denne rapporten ord for ord. Denne vanskelige prosessen er muliggjort takket være den enorme styrken som ligger i det underliggende vitenskapelige og faglige materialet som IPCCs rapporter bygger på. Panelet ble opprettet i 1988 ved en resolusjon vedtatt av FNs Generalforsamling. Ett av avsnittene er viktig fordi det der ble sagt: “Merker seg med bekymring at den dokumentasjonen som begynner å dukke opp tyder på at fortsatt vekst i atmosfæriske konsentrasjoner av “drivhus”-gasser kan føre til global oppvarming med en mulig stigning i havnivået, noe som vil få katastrofale følger for menneskeheten hvis det ikke treffes tiltak på alle nivåer i tide”. Dette betyr at FN for knapt tjue år siden var fullstendig klar over muligheten for en katastrofe som følge av klimaendringer gjennom en stigning i havnivået. I dag vet vi veldig mye mer, noe som gir enda mer substans til denne bekymringen.

Det å gi denne æresbevisningen til IPCC mener vi egentlig strekker seg ut over selve bekymringen for hvordan klimaendringer virker inn på freden. Berge Furre uttrykte et velformulert prinsipp under Nobelmiddagen 10. desember 2004 da han sa at: “Vi hedrer jordkloden fordi den gir oss blomster og mat – og trær … Den norske Nobelkomiteen er opptatt av å verne om jordkloden. Dette engasjementet er vår dypfølte visjon – og den er forbundet med menneskerettigheter og fred”. Det å hedre IPCC gjennom tildelingen av Nobels fredspris for 2007 kan innerst inne ses på som en tydelig kunngjøring av at vi må beskytte kloden mot de omfattende virkningene av klimaendringene. Det at Panelet ble valgt som mottaker av denne fremstående prisen, er etter vår oppfatning en anerkjennelse av tre viktige kjensgjerninger, som kan oppsummeres som:

- En kraftig og løfterik felles vitenskapelig bestrebelse kan, slik IPCC har vist det, strekke seg ut over landegrensene og de politiske forskjellene når det gjelder å arbeide for å nå mål som ivaretar de overordnede interessene i samfunnet.

- Betydningen av den rollen som kunnskapen spiller når det gjelder å forme den offentlige politikken og å vise vei for globale tiltak for bærekraftig utvikling i samfunnet.

- En anerkjennelse av det som truer stabiliteten og menneskers trygghet som følge av virkningene av et klima i endring og derfor behovet for å utarbeide en effektiv logisk begrunnelse for rettidige og riktige tiltak med henblikk på å unngå slike trusler i fremtiden.

Disse tre kjensgjerningene omslutter en viktig sannhet som må være retningsgivende for global handling fra hele menneskeheten i fremtiden. Når man som jeg kommer fra India, hvor det tidlig oppstod en tidlig sivilisasjon og hvor mye av tidligere tiders tradisjon og visdom viser vei selv i den moderne tidsalder, må filosofien om “Vasudhaiva Kutumbakam”, som betyr at hele universet er én og samme familie, prege hele den globale innsatsen for å forsvare det vi alle har til felles. Dette prinsippet er avgjørende for å opprettholde fred og orden i dag og enda mer i årene som kommer, slik den velkjente spaltisten og forfatteren Thomas Friedman har påpekt det i sin bok “The World is Flat”.

Dersom vi unnlater å ta vare på den arven vi har fått i form av naturressurser, vil dette kunne slå ekstremt uheldig ut for menneskeheten og for alle arter som lever sammen på jordkloden. Det finnes nemlig mange lærdommer å trekke fra menneskehetens historie som burde utgjøre en sterk nok advarsel om det kaoset og den ødeleggelsen som venter oss hvis vi fortsetter å gjøre oss skyldig i en nærsynt likegyldighet i forhold til den gradvise erosjonen og forringelsen av naturressursene. Mye har for eksempel vært skrevet om mayasivilisasjonen, som hadde sin storhetstid fra år 250 til år 950 e.Kr., men som kollapset hovedsakelig på grunn av en alvorlig og langvarig tørke. Også før dette, for ca. 4000 år siden, forsvant en rekke velkjente bronsealderkulturer som spredte seg helt fra Middelhavet til Indusdalen, herunder også de sivilisasjonene som hadde blomstret opp i Mesopotamia. Nyere eksempler på samfunn som har kollapset eller hvor det har oppstått kaos på grunn av at naturressursene er blitt uttømt eller forringet er Khmerriket i Sørøst-Asia, Eastern Island og flere andre. Klimaendringer har opp gjennom historien vært bestemmende for perioder med både fred og konflikt. Det arbeidet David Zhang nylig har gjennomført har bidratt til å belyse sammenhengen mellom temperatursvingninger, nedsatt landbruksproduksjon og hyppigheten av krigføring i det østlige Kina i løpet av de siste tusen år. I de siste par årene har for øvrig flere grupper forsket på forholdet mellom klima og sikkerhet. Disse har tatt for seg trusselen som oppstår ved dramatiske migrasjoner, konflikt og krig om vann og andre ressurser, samt omstilling av maktbalansen mellom nasjoner. Enkelte påpeker også muligheten av økt spenning mellom rike og fattige nasjoner, helseproblemer forårsaket fremfor alt av vannmangel, samt feilslåtte avlinger og bekymringer knyttet til spredningen av atomkraft.

En av de mest betydningsfulle sidene ved virkningene av klimaendringer, som dessverre ikke har fått nok oppmerksomhet fra samfunnsvitenskapelige forskere, er hvordan de endringene som er i ferd med å inntreffe og som trolig vil komme til å inntreffe i fremtiden vil slå ut fra et rettferdighetsperspektiv. Generelt sett vil virkningene av klimaendringene på noen av de fattigste og mest sårbare samfunnene i verden, kunne vise seg å bli uhyre destabiliserende. Tatt i betraktning at enkelte av disse samfunnene kjennetegnes av mangelfull kapasitet, økonomisk styrke og institusjonelle rammer, vil de være svært sårbare for virkningen av klimaendringene og de vil derfor komme til å oppleve at den økonomiske situasjonen svekkes, med tap av levebrød og muligheten for å opprettholde et eksistensgrunnlag. Siden IPCC ikke er den type organisasjon som utarbeider vurderinger som er normative for politikken, er det ikke gitt noen føringer på hvordan konflikter i tilknytning til de sosiale følgene av klimaendringer kan unngås eller begrenses. Den fjerde hovedrapporten inneholder imidlertid vitenskapelige funn som andre forskere kan studere nærmere og trekke konklusjoner av i forhold til spørsmålet om fred og sikkerhet. Flere deler av våre rapporter inneholder mye informasjon og kunnskap som vil kunne være svært nyttig for enkeltforskere og tankesmier som arbeider med sikkerhetsspørsmål, samt for regjeringer som nødvendigvis vil måtte være opptatt av slike spørsmål. Det ville være spesielt relevant å gjennomføre dyptpløyende analyser av den sikkerhetsmessige risikoen for de mest sårbare sektorene og samfunn som rammes av klimaendringer på verdensbasis.

Fred kan defineres som sikkerhet og sikker tilgang til ressurser som er nødvendige for å kunne leve. Hvis denne tilgangen bryter sammen, vil også freden kunne bryte sammen. I den forbindelse vil klimaendringer slå ut på mange områder siden de forventes å ha en rekke negative følger for enkelte befolkningsgrupper når det gjelder:

– tilgang til rent vann,

– tilgang til nok mat,

– stabile helseforhold,

– økosystem-ressurser,

– trygghet for bosettinger.

Det er forventet at klimaendringer vil forverre dagens press på vannressursene. På det regionale plan spiller snømassene i fjellene, isbreene og små iskapper en avgjørende rolle for tilgangen på ferskvann. Den utstrakte nedgangen i isbremasser og i snødekket som har funnet sted over de siste ti årene, forventes å skulle skyte fart i løpet av det 21. århundre, noe som vil redusere tilgangen på vann, potensialet for vannkraftutbygging og den sesongbetonte tilgangen på smeltevann i regioner i større fjellkjeder (f.eks. Hindu-Kush, Himalaya, Andesfjellene), hvor mer enn en sjettedel av verdens befolkning lever i dag. Det er også høy grad av sikkerhet for at mange halvtørre områder (f.eks. Middelhavsområdet, den vestlige delen av USA, det sørlige Afrika og det nordøstlige Brasil) vil oppleve en nedgang i vannressursene som følge av klimaendringer. I Afrika er det forventet at mellom 75 og 250 millioner mennesker innen 2020 vil oppleve et økt press på vannressursene på grunn av klimaendringene.

Klimaet kan i tillegg komme til å slå negativt ut for matvaresikkerheten og forverre underernæringen på sørlige breddegrader, særlig i regioner med tørke- og regntid, hvor det forventes at avlingenes produktivitet kommer til å falle selv ved mindre, lokale temperaturøkninger (1–2 °C). I enkelte afrikanske land vil avkastningen av landbruksproduksjonen som er basert på regnvann kunne bli redusert med inntil 50 % innen 2020. Det forventes av landbruksproduksjonen i mange afrikanske land, herunder også tilgangen til mat, står i fare for å bli alvorlig rammet.

Det er forventet at helsetilstanden for millioner av mennesker vil bli påvirket av for eksempel økt underernæring og antall dødsfall, sykdommer samt skader forårsaket av ekstremværhendelser, vil øke. Det vil bli en økt belastning i form av diarésykdommer, økt forekomst av hjerte-lungesykdommer som følge av høyere konsentrasjoner av oson på bakkenivå i byområder på grunn av klimaendringer og en endret geografisk fordeling av visse smittsomme sykdommer.

Klimaendringene vil sannsynligvis få visse irreversible konsekvenser for det biologiske mangfoldet. Det er middels sikkerhet for at rundt 20 %–30 % av de artene som er vurdert så langt, sannsynligvis vil være i større fare for å bli utryddet dersom den gjennomsnittlige globale oppvarmingen overstiger 1.5–2.5 ºC, sammenlignet med med tallene for 1980-99. Hvis den globale gjennomsnittlige temperaturøkningen overstiger ca. 3.5 ºC, tyder modellberegninger på at en rekke arter på jordkloden (40 %–70 % av de vurderte artene) vil bli utryddet. Dersom disse endringene skulle inntreffe, ville det få alvorlige følger for flere økesystemers bærekraftighet og for de tjenestene som de gjør for menneskeheten.

Når det gjelder tryggheten for menneskelige bosettinger, er sårbarheten for klimaendringer generelt sett større i visse høyrisiko-områder, særlig langs kysten og elver, samt i områder hvor økonomien er nært knyttet til klimasensitive ressurser. Der hvor ekstremværhendelser blir mer intense eller hyppige på grunn av klimaendringene, vil de økonomiske og sosiale kostnadene ved slike hendelser øke.

Enkelte regioner vil trolig bli spesielt hardt rammet av klimaendringene.

– Arktis, på grunn av den virkningen den forventede sterke oppvarmingen vil få på natursystemer og samfunn,

– Afrika, på grunn av lav tilpasningsevne og den forventede effekten av klimaendringene,

– Mindre øyer, hvor befolkning og infrastruktur er svært sårbar for den forventede effekten av klimaendringene,

– Megadeltaer i Asia og Afrika, på grunn av store befolkningsgrupper og sårbarhet for stigninger i havnivået, stormbølger og elveoversvømmelser.

IPCCs fjerde hovedrapport konkluderer med at press som ikke er knyttet til klimaet kan øke sårbarheten for klimaendringer ved å redusere robustheten og tilpasningsevnen fordi ressursene kanaliseres mot konkurrerende behov. Sårbare regioner står overfor flere typer press som påvirker deres utsatthet og sårbarhet for ulike virkninger samt deres tilpasningsevne. Dette presset oppstår for eksempel som et resultat av dagens klimafarer, fattigdom og ulik tilgang til ressurser, matvareusikkerhet, tendenser innen økonomisk globalisering, konflikt og forekomst av sykdommer som HIV/AIDS.

I andre områder, selv områder med høye inntekter, vil enkelte (som for eksempel de fattige, små barn og eldre) være spesielt utsatt.

Migrasjon og forflytning av folkemasser er en særlig viktig kilde til mulige konflikter. Migrasjon, som vanligvis er midlertidig og ofte handler om flytting fra landsbygda til byområder, er en vanlig reaksjon ved naturkatastrofer som flom og hungersnød. Men akkurat som det ved sårbarhet for virkningene av klimaendringer kan oppstå krysspress på grunn av mange ulike årsaker og forhold, kan det også ved migrasjon være slik at enkeltindivider motiveres av ulike faktorer og at mennesker kan bli fordrevet på grunn av ulike faktorer.

Et annet spørsmål som gir grunn til stor bekymring, er funn som viser at menneskeskapte faktorer kan føre til visse brå eller irreversible virkninger, avhengig av takten på og omfanget av klimaendringen. For eksempel vil et delvis tap av isdekket i polare landområder kunne føre til at havnivået stiger med flere meter, at det skjer store endringer i kystlinjene og at lavtliggende områder blir oversvømt, og her vil virkningen bli aller størst for elvedeltaer og lavtliggende øyer.

En gjennomsnittlig global oppvarming på over ca. 4.5 ºC sammenlignet med 1980–99 (ca. 5 ºC over det førindustrielle nivået) vil føre til:

– En beregnet nedgang i nedbør på inntil 20 % i mange tørre tropiske og subtropiske områder.

– Et forventet tap av ismassen på Grønland vil, hvis tapet vedvarer i flere hundre år (basert på alle dagens globale klimasystemmodeller som er evaluert), føre til at havnivået stiger med opptil 4 meter og dermed vil kystlinjen på alle kontinenter bli oversvømt.

Hvis dette skulle skje, ville følgene av disse endringene bli alvorlige og katastrofale. Det er imidlertid mulig for menneskeheten å møte disse truslene. Virkningene av klimaendringene kan begrenset ved hjelp av tilpassede tiltak og strenge utslippsreduserende tiltak for klimagasser.

Samfunnet har en lang historie bak seg med tilpasninger til virkningene av vær og klima. Klimaendringene innebærer imidlertid nye risikofaktorer som ofte ligger utenfor den erfaringen vi har tilegnet oss, som for eksempel virkninger knyttet til tørke, hetebølger, rask isbresmelting og intense orkaner. Disse virkningene fordrer tilpassede tiltak som for eksempel investeringer i beskyttelse mot stormer og i vannforsyningsinfrastruktur, samt i lokale helsetjenester. Tilpasningstiltak som er nødvendige for å redusere denne sårbarheten blir sjelden gjennomført kun som en konsekvens av klimaendringene, men kan inkluderes i for eksempel tiltak for å forvalte vannressursene, ivareta kystområdene og i risikoreduserende strategier. Verdenssamfunnet må samordne sin innsats og bli mer proaktiv når det gjelder å gjennomføre tilpasningstiltak for verdens mest sårbare samfunn og systemer.

Tilpasning står helt sentralt når man skal takle de virkningene som følger av oppvarmingen og som allerede nå er uunngåelige på grunn av tidligere utslipp. Men tilpasning alene er ikke nok til å takle alle de forventede virkningene av klimaendringene, og særlig ikke på lang sikt siden omfanget av de fleste virkningene bare vil øke.

Det finnes et stort potensiale for å gjennomføre utslippsreduserende tiltak for klimagasser i løpet av de kommende tiårene slik at man kan oppveie for den forventede veksten i globale utslipp eller redusere utslippene til under dagens nivå. Det finnes mange faktorer som kan drive frem tiltak som kan redusere klimagassutslippene, og de kan gi en rekke fordeler på lokalt plan i form av økonomisk utvikling og fattigdomsreduksjon, sysselsetting, energisikkerhet og lokalt miljøvern.

Den fjerde hovedrapporten har anslått kostnadene ved klimatiltak i løpet av de kommende tiårene for en rekke scenarier med stabilisering av konsentrasjonen av klimagasser og korresponderende økninger i global gjennomsnittlig likevektstemperatur. Et stabiliseringsnivå på 445–590 ppm i CO2-ekvivalenter, noe som tilsvarer en økning i global gjennomsnittstemperatur på 2,0–2,4 ºC over førindustrielt nivå (med beste estimat for klimafølsomhet), vil føre til en nedgang i gjennomsnittlig årlig BNP-vekst på mindre enn 0,12 % frem til 2030 og videre til 2050. Hovedsakelig vil nedgangen i globalt BNP med den minst kostbare banen som er vurdert for dette stabiliseringsnivået, ligge på under 3 % i 2030 og på under 5,5 % i 2050. Visse viktige trekk ved dette stabiliseringsscenariet må nøye vurderes:

– For å stabilisere konsentrasjonen av CO2-ekvivalenter på 445–490 ppm, vil CO2-utslippene måtte nå en topp i perioden 2000–15 for deretter å falle. Vi har derfor et kort tidsvindu på oss for å få til en nedgang i det globale utslippet hvis vi ønsker å begrense temperaturøkningen til om lag 2 ºC når likevekt er oppnådd.

– Selv et så ambisiøst stabiliseringsnivå vil føre til en gjennomsnittlig havnivåstigning på 0,4–1,4 meter når likevekt er oppnådd bare på grunn av termisk ekspansjon. Dette vil få alvorlige konsekvenser for en rekke regioner og steder i verden.

En rasjonell tilnærming til risikoforvaltning forutsetter at samfunnet vurderer virkningene av klimaendringer gjennom et scenario hvor man fortsetter som før og at man tallfester kostnadene samt de skader som det er umulig å tallfeste ved en slik hypotese, og setter dette opp mot kostnadene ved å gjennomføre tiltak. Med en slik tilnærming vil resultatene helt klart gå i favør av omfattende klimatiltak. Selv med dagens konsentrasjonsnivå av klimagasser, vil virkningene av klimaendringene være alvorlige nok til å rettferdiggjøre strenge utslippsbegrensende tiltak. Dersom konsentrasjonen av alle klimagasser og aerosoler hadde blitt holdt på samme nivå som i 2000, måtte vi ha forberedt oss på en ytterligere økning på ca. 0,1 ºC pr. tiår. Senere temperaturberegninger vil være avhengige av hvilke utslippsscenarier man legger til grunn. De systemene og de samfunn som er utsatt, vil kunne rammes hardt selv av mindre klimaendringer.

Vitenskapen forteller oss ikke bare at klimasystemene er i ferd med å endre seg, men også at det i fremtiden vil oppstå ytterligere oppvarming og stigning i havnivået selv om klimagassnivået skulle stabilisere seg i dag. Dette skyldes den grunnleggende fysikken i systemet. Sosiale faktorer bidrar også til vår fremtid, herunder den “fastlåste” situasjonen vi er havnet i for eksempel på grunn av dagens kraftanlegg, transportsystemer og bygninger, som trolig vil fortsette å gi utslipp selv når renere infrastruktur blir tatt i bruk i fremtiden. Ikke nok med at vi står overfor en stor utfordring, men det er også en utfordring hvor hvert år med utsettelse vil føre til stadig større klimaendringer i fremtiden.

Det er på sin plass å minne om hva president Gayoom fra Maldivene sa på det 42. møtet i FNs Generalforsamling 19. oktober 1987:

“Når det gjelder mitt land, Maldivene, vil en gjennomsnittlig stigning i havnivået på 2 meter være tilstrekkelig til at hele landet praktisk talt vil forsvinne under vann, med sine 1.190 små øyer hvorav de fleste knapt rager 2 meter over gjennomsnittlig havnivå. Det ville bety undergangen for en nasjon. Selv med en stigning på bare 1 meter, ville en stormbølge bli katastrofal og muligens skjebnesvanger for nasjonen.”

22. september 1997, under åpningen av IPCCs 13. møte i Male, hovedstaden på Maldivene, minnet president Gayoom oss om den trusselen hans land er utsatt for ved å fortelle at: “For ti år siden, i april 1987, stod det stedet hvor vi nå er samlet 60 cm under vann, etter at uvanlig høye bølger hadde lagt en tredjedel av Male under vann, også den internasjonale flyplassen i Male og flere av de andre øyene i øygruppen.” De farefulle virkningene av klimaendringene er altså i dag en realitet i enkelte deler av verden, og vi kan ikke gjemme oss bak globale gjennomsnitt og velstående samfunns evne til å håndtere klimarelaterte trusler for å slippe å se hvordan situasjonen er for sårbare samfunn i fattige regioner på kloden.

Alle de hovedrapporter IPCC har offentliggjort siden 1990 viser at det er gjort fremskritt når det gjelder den vitenskapelig kunnskapen om klimaendringer og konsekvensene av disse. Disse fremskrittene har vært mulige fordi man har kombinert den styrken som ligger i en stadig mer omfattende dokumentasjon av observerte klimaendringer, den store arbeidsinnsatsen som er utført av forskningsmiljøene og en forbedret formidling av vitenskapelige arbeider. Vi har nå mer vitenskapelig dokumentasjon av realiteten bak klimaendringene og hvordan menneskene har bidratt til disse. Som den fjerde hovedrapporten sier: “oppvarmingen av klimasystemet er utvetydig”, og “det er svært sannsynlig at det meste av den globale oppvarmingen over de siste 50 årene skyldes en økning i menneskeskapte klimagasser”.

Det må gjøres ytterligere fremskritt i den vitenskapelige vurderingen slik at man kan støtte opp under sterke og hensiktsmessige tiltak for å møte trusselen ved klimaendringer, herunder å utforme en politikk for tilpasning og utslippsreduserende tiltak.

Det er også en merkbar mangel på geografiske data og litteratur om observerte endringer, særlig for utviklingslandenes del. Fremtidige endringer i isdekket på Grønland eller i Arktis er en annen stor kilde til usikkerhet som vil kunne øke prognosene for havnivåstigningen. Behovet for ytterligere innspill fra det vitenskapelige miljøet forutsetter at de som utformer politikken og samfunnet som helhet fortsetter å stole på og samarbeide med de som utfører slike vitenskapelige arbeider.

Hvordan klimaendringene vil påvirke freden er det opp til andre å avgjøre, men vi har kommet med en vitenskapelig vurdering av hva som kan komme til å utløse konflikter. Da Willy Brandt holdt sin takketale etter å ha mottatt Nobels fredspris i 1971, sa han: “… vi må vite mer om hvordan konflikter oppstår. … Slik jeg ser det, er det i vår verden, i tillegg til det å føre en fornuftlig politikk, ikke noe annet troverdig alternativ til maktbruk enn læring.”

Den 13. konferansen for partene til FNs rammekonvensjon om klimaendringer pågår på Bali akkurat nå. Verdens oppmerksomhet er rettet mot dette møtet og det er håp om at denne konferansen, i motsetning til de siste årenes ufruktbare møter, skal kunne føre til positive resultater. IPCCs arbeid har hjulpet verden til å lære mer om alle sider ved klimaendringer, og dette er noe den norske Nobelpriskomiteen har anerkjent. Spørsmålet er om deltakerne på Bali vil støtte det Willy Brandt kalte en “fornuftig politikk”. Vil beslutningstakerne som er ansvarlige for klimaendringer på det globale plan lytte til vitenskapens og kunnskapens klare og tydelige stemme? Hvis de gjør dette på Bali og senere, vil alle mine kolleger i IPCC og de mange tusener av mennesker som jobber i vitenskapens tjeneste føle seg dobbelt beæret over den hedersbevisningen som jeg mottar her i dag på deres vegne.