Hans Bethe – Nominations

Speed read: Stellar nuclear reactors

“Why does the Sun shine?” is one of those questions asked by curious children to which adults struggle to provide a convincing answer. Hans Bethe received the 1967 Nobel Prize in Physics for revealing how the Sun behaves like a giant nuclear reactor to produce the vast amount of heat and light that supports life on Earth.

Bethe’s breakthrough work stems from the British astronomer Sir Arthur Eddington’s hypothesis in the 1920s that the intense temperatures and pressures within the Sun can force the nuclei of atoms to fuse and create heavier atoms, releasing a tremendous amount of energy in the process. Drawing upon his series of articles that provided a comprehensive account of the central components of atoms and the manner in which these atomic nuclei interact with each other, Bethe applied this knowledge to understanding the stars.

In two papers in 1938 and 1939 Bethe described the two nuclear reactions that stars use to produce energy, and showed how one predominates over the other depending on the internal conditions. For stars up to and including the size of the Sun, the more dominant energy supply is generated by squeezing four hydrogen nuclei together to form one helium nucleus. In the more extreme temperatures and pressures found in stars that are heavier than our Sun, the dominant energy supply also transforms hydrogen into helium, but this involves a more complex cycle of nuclear reactions in which carbon acts as a catalyst. Albert Einstein‘s most famous equation, E=mc2, showing that mass and energy are interchangeable, explains why these fusion reactions create heat and light. The mass of helium is less than the sum of the hydrogen nuclei, and the difference in mass is converted into large quantities of energy.

According to Bethe’s theories, these reactions ensure there is enough energy to allow the Sun to shine for billions of years, considerably longer than previous estimates had predicted. Bethe’s theories have also helped us to imagine stars existing in a form of life cycle. Stars are born, they grow and develop by burning fuel, but at some point this energy source must burn out, and eventually they die.

Hans Bethe – Nobel Lecture

Nobel Lecture, December 11, 1967

Energy Production in Stars

Read the Nobel Lecture

Pdf 899 kB

Hans Bethe – Banquet speech

Hans Bethe’s speech at the Nobel Banquet in Stockholm, December 10, 1967

Your Majesty, Your Royal Highnesses, Ladies and Gentlemen.

I am deeply grateful to you for bestowing on me the Nobel Prize. For many decades this Prize has been regarded as the highest honor which can be awarded to a scientist. I feel quite humble comparing myself with many of my predecessors who have made great and fundamental discoveries. You have given me the Prize I believe for a lifetime of quiet work in physics rather than for any spectacular single contribution. I am very proud and very happy with this distinction.

One of the happiest parts has been the response of so many of my friends. I have received many hundreds of letters and telegrams of congratulations, and it seems to me that all of them really shared my joy about the Prize. Many more, I suppose, were happy about it without telling me directly. And I suppose that the same is true for every Nobel Prize; it is enjoyed not only by the recipient, but by many others.

Mr. Nobel, when he started the Nobel Prize, can hardly have known how many people he would make happy. He probably thought of the future prize winners, and that he would make their scientific life easier and more pleasant. But he probably did not imagine that with each prize he would bring happiness to hundreds of others as well.

In our country we often try to persuade rich men to leave their money to universities. This is certainly a good cause and, if the same custom applies here in Sweden, Nobel might well have left his fortune to for instance the University of Uppsala. This would have been of great benefit to that university, and perhaps especially to the pursuit of science there. However, these benefits could not remotely compare to those which Nobel achieved by establishing the Prizes. They have stimulated science all over the world; they have stimulated governments and universities to give more support to science; and they have added prestige to science in the eyes of young students.

That the Prizes have acquired this prestige is of course mostly the merit of the Swedish Royal Academy. I have sat on committees to select the recipients for lesser prizes, and I know what a hard job it is. It must be enormously more troublesome for the Nobel Prizes. I have always admired the selections they have made, and I am not saying this because I am one of the lucky ones.

We are all unhappy that nobody today will receive the Peace Prize. Unfortunately it is not surprising in the present world that the Norwegian Parliament could not find anybody who has contributed sufficiently to peace to merit the Prize. I believe I express the hope of all of us that a Peace Prize can be given next year.

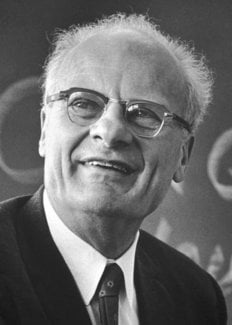

Hans Bethe – Photo gallery

Hans Bethe receiving his Nobel Prize from His Majesty the King Gustaf VI Adolf of Sweden at the Stockholm Concert Hall, 10 December 1967.

By Scanpix, public domain via Wikimedia Commons

Hans Bethe – Other resources

Links to other sites

Three video lectures by Hans Bethe from Cornell University

‘Hans Bethe’s Interview’ from Voices of the Manhattan Project

On Hans Bethe from American Institute of Physics

The Nobel Prize in Physics 1967

Hans Bethe – Biographical

Hans Albrecht Bethe was born in Strasbourg, Alsace-Lorraine, on July 2 1906. He attended the Gymnasium in Frankfurt from 1915 to 1924. He then studied at the University of Frankfurt for two years, and at Munich for two and one half years, taking his Ph. D. in theoretical physics with Professor Arnold Sommerfeld in July 1928.

He then was an Instructor in physics at Frankfurt and at Stuttgart for one semester each. From fall 1929 to fall 1933 his headquarters were the University of Munich where he became Privatdozent in May 1930. During this time he had a travel fellowship of the International Education Board to go to Cambridge, England, in the fall of 1930, and to Rome in the spring terms of 1931 and 1932. In the winter semester of 1932-1933,he held a position as Acting Assistant Professor at the University of Tubingen which he lost due to the advent of the Nazi regime in Germany.

Bethe emigrated to England in October 1933 where he held a temporary position as Lecturer at the University of Manchester for the year 1933-1934, and a fellowship at the University of Bristol in the fall of 1934. In February 1935 he was appointed Assistant Professor at Cornell University, Ithaca, N. Y. U.S.A., then promoted to Professor in the summer of 1937. He has stayed there ever since, except for sabbatical leaves and for an absence during World War II. His war work took him first to the Radiation Laboratory at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, working on microwave radar, and then to the Los Alamos Scientific Laboratory which was engaged in assembling the first atomic bomb. He returned to Los Alamos for half a year in 1952. Two of his sabbatical leaves were spent at Columbia University, one at the University of Cambridge, and one at CERN and Copenhagen.

Bethe’s main work is concerned with the theory of atomic nuclei. Together with Peierls, he developed a theory of the deuteron in 1934 which he extended in 1949. He resolved some contradictions in the nuclear mass scale in 1935. He studied the theory of nuclear reactions in 1935-1938, predicting many reaction cross sections. In connection with this work, he developed Bohr’s theory of the compound nucleus in a more quantitative fashion. This work and also the existing knowledge on nuclear theory and experimental results, was summarized in three articles in the Reviews of Modern Physics which for many years served as a textbook for nuclear physicists.

His work on nuclear reactions led Bethe to the discovery of the reactions which supply the energy in the stars. The most important nuclear reaction in the brilliant stars is the carbon-nitrogen cycle, while the sun and fainter stars use mostly the proton-proton reaction. Bethe’s main achievement in this connection was the exclusion of other possible nuclear reactions. The Nobel Prize was given for this work, as well as his work on nuclear reactions in general.

In 1955 Bethe returned to the theory of nuclei, emphasizing a different phase. He has worked since then on the theory of nuclear matter whose aim it is to explain the properties of atomic nuclei in terms of the forces acting between nucleons.

Before his work on nuclear physics, Bethe’s main attention was given to atomic physics and collision theory. On the former subject, he wrote a review article in Handbuch der Physik in which he filled in the gaps of the existing knowledge, and which is still up-to-date. In collision theory, he developed a simple and powerful theory of inelastic collisions between fast particles and atoms which he has used to determine the stopping power of matter for fast charged particles, thus providing a tool to nuclear physicists. Turning to more energetic collisions, he calculated with Heitler the bremsstrahlung emitted by relativistic electrons, and the production of electron pairs by high energy gamma rays.

Bethe also did some work on solid-state theory. He discussed the splitting of atomic energy levels when an atom is inserted into a crystal, he did some work on the theory of metals, and especially he developed a theory of the order and disorder in alloys.

In 1947, Bethe was the first to explain the Lamb-shift in the hydrogen spectrum, and he thus laid the foundation for the modern development of quantum electrodynamics. Later on, he worked with a large number of collaborators on the scattering of pi mesons and on their production by electromagnetic radiation.

Bethe is married to the daughter of P.P. Ewald, the well-known X-ray physicist. They have two children, Henry and Monica.

This autobiography/biography was written at the time of the award and first published in the book series Les Prix Nobel. It was later edited and republished in Nobel Lectures. To cite this document, always state the source as shown above.

Hans Bethe died on March 6, 2005.

Hans Bethe – Facts

Award ceremony speech

Presentation Speech by Professor O. Klein, member of the Swedish Academy of Sciences

Your Majesty, Your Royal Highnesses, Ladies and Gentlemen.

This year’s Nobel Prize in Physics – to professor Hans A. Bethe – concerns an old riddle. How has it been possible for the sun to emit light and heat without exhausting its source not only during the thousands of centuries the human race has existed but also during the enormously long time when living beings needing the sun for their nourishment have developed and flourished on our earth thanks to this source? The solution of this problem seemed even more hopeless when better knowledge of the age of the earth was gained. None of the energy sources known of old could come under consideration. Some quite unknown process must be at work in the interior of the sun. Only when radioactivity, its energy generation exceeding by far any known fuel, was discovered, it began to look as if the riddle might be solved. And, although the first guess that the sun might contain a sufficient amount of radioactive substances soon proved to be wrong, the closer study of radioactivity would by and by open up a new field of physical research in which the solution was to be found.

While ordinary physics and chemistry could be led back to the behaviour of the electrons which form the outer part of atoms, the new field is concerned with their innermost part, the atomic nucleus. Its discoverer, Rutherford, called it the newer alchemy because nuclear reactions, in contrast to chemical reactions, usually lead to transmutations of the chemical elements – what alchemists wished to produce but could not by their means-the reaction energy being there some million times greater than in chemical reactions.

It soon became clear that the proton, the nucleus of the hydrogen atom, is a common building stone of all atomic nuclei. It is electrically charged. The other building stone, the neutron, being electrically neutral as indicated by its name, was discovered in 1932, twenty-one years later than the nucleus itself. And, in spite of important progress during those years, it may be said that from then on nuclear physics had really started. At that time it was already apparent that Bethe belonged to the small group of young theoretical physicists who through skill and knowledge were particularly qualified for tackling the many theoretical problems turning up in close connection with the rapidly appearing experimental discoveries. The centre of these problems was to find the properties of the force that keeps the protons and neutrons together in the nucleus, the counterpart of the electric force which binds the atomic electrons to the nucleus. Bethe’s contributions to the solution of these problems have been numerous and are still continuing. They put him clearly in the first row among the workers in this field – as in several other fields. Moreover, about the middle of the thirties he wrote, partly alone, partly together with some colleagues, what nuclear physicists at the time used to call the Bethe bible, a penetrating review of about all that was known of atomic nuclei, experimental as well as theoretical.

This extensive and profound knowledge of his regarding atomic nuclei together with a rare gift of rapidly grasping the essence of a physical problem and finding ways of solving it explains that Bethe could so swiftly do the work awarded by the Nobel Prize. He started his work after a conference taking place in Washington in March 1938 and the paper containing a thorough description of it was delivered for print at the beginning of September the same year. During that conference and afterwards he seems also to have acquired the necessary astrophysical knowledge. This knowledge depended mainly on a pioneer work by Eddington from the year 1926, according to which the innermost part of the sun is a hot gas mainly consisting of hydrogen and helium. Owing to the high temperature, about 20 million degrees, – these atoms being dissolved into electrons and nuclei – the mixture, despite the high density – about 80 times that of water – really behaves like a gas. The amount of energy generation necessary to maintain this state was known from measurements of the radiation falling on the earth. Taken as a whole it is enormous, but very slow as compared to the size of the sun. An ordinary 60-Watt electric bulb would correspond to about 300 tons average sun matter. This very slow burning together with the very high energy release from a given weight of fuel gives this source the high durability required by geology and the long existence of life on the earth.

Before coming to the nuclear processes, which according to Bethe’s work are definitely the source of the energy generation of the sun and similar stars, a few words should be said about two questions which naturally present themselves in this connection. Why are these nuclear processes so slow in the sun when they are so fast in atomic reactors, not to mention atomic bombs? And why are they non-existent under ordinary conditions? The answer is that nuclei are protected against other nuclei by the repulsion due to their electric charges together with the extremely small range of the nuclear force – which is about as small relative to a midget as a midget is to the sun – implying that a proton must have an extremely high velocity in order to come so close to another nucleus as is necessary for a nuclear reaction to take place. If it were not for the quantum-mechanical tunnel effect studied very closely in this connection by Gamow – who must be considered the main forerunner of Bethe with respect to the application of nuclear physics to astronomy – even the velocities of the protons at the high temperature of the sun would not be able to produce any such processes. But through this effect the required slow reactions do occur. The case of the atomic reactors is different, because the reactions are there produced by neutrons, which having no charge are not stopped by the electric charge of the nuclei. Fortunately neutrons are short-lived and therefore extremely rare under ordinary circumstances and also in the sun.

Even when Bethe started his work on the energy generation in stars there were important gaps in the knowledge about nuclei which made the solution of the problem very difficult. And it was by a remarkable combination of underdeveloped theory and incomplete experimental evidence, under repeated comparison of his conclusions with their astronomical consequences, that he succeeded in establishing the mechanism of energy generation in the sun and similar stars so well that only minor corrections were needed when many years later the required experimental knowledge had made considerable progress and when, moreover, electronic computers had become available for the numerical calculations.

A very important part of his work resulted in eliminating a great number of thinkable nuclear processes under the conditions at the centre of the sun, after which only two possible processes remained. The simplest of them begins with two protons colliding and forming a nucleus of heavy hydrogen, the surplus of electric charge vanishing in the form of a positive electron. After capturing a few more protons the result of the process is the formation of a helium nucleus from four protons. Thereby the energy release from a given weight of hydrogen is nearly 20 million times greater than that produced by burning the same weight of carbon into carbon dioxide. The second process is more complicated. It requires the presence of carbon which, however, will practically not be consumed but acts as a catalyst, the result being the same as in the former process. It should be mentioned that the first process had been proposed a few years earlier by Atkinson and later discussed by von Weizsacker, who also considered the second process independently of and at about the same time as Bethel But none of them had attempted a thorough analysis of these and other thinkable processes necessary to make it reasonably certain that these processes, and only these, are responsible for the energy generation in the sun and similar stars.

Bethe’s work constitutes since many years a main foundation for the great development which has taken place of the knowledge of the interior of the sun and the stars. During recent years it has obtained a new actuality through a promising attempt made by a group of astrophysicists to understand what happens when a star has used up its hydrogen, thereby throwing new light on another old riddle, that of the origin of the chemical elements.

Professor Bethe. You may have been astonished that among your many contributions to physics, several of which have been proposed for the Nobel Prize, we have chosen one which contains less fundamental physics than many of the others and which has taken only a short part of your long time in science. This, however, is quite in agreement with the rules of the Nobel Prize and does not imply that we are not highly impressed by the role you have played in so many parts of the development of physics ever since you started doing research some forty years ago. On the other hand your solution of the energy source of stars is one of the most important applications of fundamental physics in our days, having led to a deepgoing evolution of our knowledge of the universe around us. On behalf of the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences I extend to you the most hearty congratulations. And now I have the privilege to ask you to receive the Nobel Prize for Physics from the hands of His Majesty the King.