Pierre-Gilles de Gennes – Photo gallery

Pierre-Gilles de Gennes receiving his Nobel Prize from H.M. King Carl XVI Gustaf of Sweden in the Stockholm Globe arena on 10 December 1991.

Nobel Foundation. Photo: Lars Åström

The 1991 Nobel Prize laureates on stage in the Stockholm Globe arena on 10 December 1991. From left: physics laureate Pierre-Gilles de Gennes, chemistry laureate Richard R. Ernst, medicine laureates Erwin Neher and Bert Sakmann, literature laureate Nadine Gordimer and laureate in economic sciences Ronald H. Coase.

Photo from the Lars Åström archive

Nobel Prize award ceremony 1991 in the Stockholm Globe arena.

Photo from the Lars Åström archive

Pierre-Gilles de Gennes delivering his speech of thanks at the Nobel Prize banquet in the Stockholm City Hall, 10 December 1991.

Nobel Foundation. Photo: Lars Åström

Pierre-Gilles de Gennes delivering his Nobel Prize lecture on 9 December 1991.

Nobel Foundation. Photo: Lars Åström

Pierre-Gilles de Gennes – Other resources

Links at other sites

On Pierre-Gilles de Gennes from American Institute of Physics

Pierre-Gilles de Gennes – Nobel Lecture

Nobel Lecture, December 9, 1991

Soft Matter

Read the Nobel Lecture

Pdf 234 kB

Pierre-Gilles de Gennes – Banquet speech

Pierre-Gilles de Gennes’ speech at the Nobel Banquet, December 10, 1991

Your Majesties, Your Royal Highnesses, Ladies and Gentlemen,

This is the first, and probably the last, time in my life where I have dinner with queens and princesses. I am worried. I suspect that with the chimes of midnight I will be turned into a pumpkin.

I have come often to this beautiful city of Stockholm. As a matter of fact, once in 1974 I attended a banquet in this very same room. This was during a conference on liquid crystals. And I was asked to give a 3 minutes talk. But in those days I still had some common sense, I said: No, this is too hard. My friend Tony Arrott took over and did very well.

But now I finally understand why I have been given this fabulous prize, not because of some scientific achievement but because the Swedes are stubborn. They wanted me to give a 3 minute talk in this hall.

Now this is done, but what remains to be said is my admiration for this country.

I was in Lund and in Stockholm 2 months ago. I was in Göteborg last Friday. I can testify that our young science of soft matter has found some of its best men or women here in Sweden.

But my words go far beyond science: I am especially proud of being distinguished in this country, the home land of Carl von Linné and Alfred Nobel – but also the land of Ingmar Bergman and Ingrid Thulin – the land which, through them, became the dream land of the world.

Merci a la Suède, et tous mes voeux pour son avenir.

<Press release

16 October 1991

The Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences has decided to award the 1991 Nobel Prize in Physics to Professor Pierre-Gilles de Gennes, College de France, Paris, France for discovering that methods developed for studying order phenomena in simple systems can be generalized to more complex forms of matter, in particular to liquid crystals and polymer.

Order and disorder in nature

This year’s Laureate, the Frenchman Pierre-Gilles de Gennes, has described mathematically how e.g. magnetic dipoles, long molecules or molecule chains can under certain conditions form ordered states, and what happens when they pass from an ordered to a disordered state. Such changes of order occur when, for example, a heated magnet changes from a state in which all the small atomic magnets are Lined up in parallel to a disordered state in which the magnets are randomly oriented. The transition from disorder to order always occurs at a well-defined temperature and can sometimes also take place in jumps. There is a phase transition at a critical temperature, which in the case of ferro-magnets is termed the Curie temperature.

Fig 1a. Magnetic order

|

| Fig 1b. Order in liquid crystals |

Pierre-Gilles de Gennes began by working on magnetic phase transitions, but during the 1960s and 1970s studied other, more complicated, order phenomena The transition to a superconducting state in certain materials, from an ordered state to a disordered state in liquid crystals; regularities in the geometrical arrangement and movement of polymer chains; conditions of stability in micro-emulsions, and other phenomena: all these have been objects of de Gennes’ interest. Some of these systems are so complicated that physicists had earlier been unable to discern general rules for how they behave during the transition from order to disorder. De Gennes has in many cases succeeded in doing this, in particular for liquid crystals and polymers. In addition, he has shown that phase transitions in such apparently widely-differing physical systems as magnets, superconductors, liquid crystals and polymer solutions can be described in mathematical terms of surprisingly broad generality.

Some examples of the laureate’s contributions

Liquid crystals have been known for over a century and their hydrodynamics, that is, how they flow, were studied as early as the 1920s by Professor Wilhelm Oseen of Uppsala. But it was not until the 1960s that the development of liquid crystals gathered impetus with the technical exploitation of their optical properties for showing numbers in pocket calculators, wristwatches, etc. Liquid crystals have been called “nature’s delicate phase of matter” because the molecules can be arranged in many different, characteristic ways, and because the arrangement is also easily affected by weak electrical or magnetic fields. One of the ordered phases is the “nematic” phase, in which the molecules move as if in an ordinary three-dimensional liquid, but with their axes mainly pointing the same way. Other phases are termed “smectic” (i.e. soap-like), where the molecules can also flow, but only in two dimensions, in parallel layers. In industry, these properties have led to the optical applications mentioned, since liquid crystals are also optically active and alter the polarisation of light or scatter light strongly when it passes through thin layers of the crystals. Recently, “flat” TV screens have been described. These are based on the electro-optical properties of liquid crystals. In physics, on the other hand, liquid crystals are often seen mainly as an exciting “playground” where the arrangements which they assume can easily be modified and studied. In these cases liquid crystals can act as model systems for experiments to test more general theories.

At the end of the 1960s de Gennes formed the liquid crystal group in Orsay. This research team consisted of both experimenters and theorists. It quickly became one of the leading groups in the field. De Gennes himself made his chief contributions to our knowledge of liquid crystals when he explained what is termed anomalous light scattering from nematic liquid crystals. This light scattering depends in a complicated manner on fluctuations in the orientational order. Another important contribution was his description of the conditions for one of the transition points that occur when a weak alternating electric field is applied. In addition, de Gcnnes demonstrated important similarities between the behaviour of liquid crystals and that of superconductors. Published in 1974, his book ‘The Physics of Liquid Crystals” has become a standard work.

Somewhat later de Gennes began to be interested in the conformation and dynamics of the polymers. Polymers are formed out of very long chains of simpler links, termed monomers. The links may be about 10 Ångstrom (i.e. 10-7 cm) long, and the chains consist of tens of thousands of similar links. Polymer molecules in dilute solutions form loops, or “tangles”, rather like spaghetti. When followed from end to end the winding-about appears like an (almost) random movement in three dimensions. Attempts had been made earlier to descnbe m mathematical-statistical terms the venous possibilities for the spatial disposition of the molecules, also taking into account the fact that a chain cannot have more than one link in the same place at the same time. The Englishman S.F. Edwards made important contributions in this area by introducing a technique of calculation taken from theoretical particle physics. De Gennes’ important discovery was that there were far more similarities than had hitherto been suspected between this “order in disorder” in the arrangement of polymers and the conditions that apply when a system of magnetic moments moves from order to disorder. With this, de Gennes opened the way for new descriptions of complicated order phenomena in polymers, which are based on general physical principles of phase transition. In the “Orsay group”, the descriptions were soon developed to apply also to polymers in more concentrated solutions, in which the various chains can partly “entangle” themselves, and in high concentrations in pure melts of polymers.

For the latter cases, de Gennes has also established a number of predictions regarding how polymer chains and their individual parts can move, i.e. what physicists call polymer dynamics. These predictions often have the character of “scaling laws”: they say that conditions shall be similar for certain combinations of the starting variables (such as polymer concentration in a solution, and temperature). These are properties that can sometimes be controlled experimentally, and many works on polymer dynamics have been performed using neutron-scattering techniques. In experiments of this kind, it is possible to distinguish how individual parts of a polymer chain move by noting how an oscillation of a selected wavelength initiated by the neutron collision is damped during a certain measurable time. Such measurements have helped to confirm de Gennes’ models for polymer-chain motion. One of these models, the “blob” model, states that a certain typical segment of a chain can move as if it were free, even in more concentrated solutions. Another is the “reptation” model, which describes the serpentine motion of a polymer chain within a “tangle” of surrounding polymer chains.

De Gennes formed a school for polymer studies as well, and gathered around him a large number of co-workers in STRASACOL a joint project with physicists and chemists from Strasbourg, Saclay and the College de France (to which de Gennes had then been appointed). His work in this field is described in his “Scaling Concepts in Polymer Physics”, which came out in 1979. De Gennes has since contributed new viewpoints in many fields unconventional for physicists such as gels, porous media and other so-called soft systems.

Fig 2. The “blob” model

Pierre-Gilles de Gennes – a coordinator in physics

Pierre-Gilles de Gennes has by some judges been called “the Isaac Newton of our time”. The reason for this highly appreciative epithet is probably that de Gennes has succeeded in perceiving common features in order phenomena in very widely differing physical systems, and has been able to formulate rules for how such systems move from order to disorder. Some of the systems de Gennes has treated have been so complicated that few physicists had earlier thought it possible to incorporate them at all in a general physical description. Physicists often take pride in dealing with systems that are as simple and “pure” as possible, but de Gennes’ work has shown that even “untidy” physical systems can successfully be described in general terms. In this way he has opened new fields in physics and stimulated a great deal of theoretical and experimental work in these fields. While this is pure research, it has also meant the laying of a more solid foundation for the technical exploitation of the materials mentioned here: liquid crystals and polymers.

Award ceremony speech

Presentation Speech by Professor Ingvar Lindgren of the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences, December 10, 1991

Translation from the Swedish text

Your Majesties, Your Royal Highnesses, Ladies and Gentlemen.

This year’s Nobel Prize in Physics has been awarded to Pierre-Gilles de Gennes, College de France, Paris, for his investigations of liquid crystals and polymers. De Gennes has shown that mathematical models, developed for studying simpler systems, are applicable also to such complicated systems. De Gennes has discovered relations between different, seemingly quite unrelated, fields of physics – connections which nobody has seen before.

Liquid crystals and polymers can be regarded as intermediate states between order and disorder. A simple crystal, such as ordinary salt, is an example of almost perfect order – its atoms or ions are located in exact positions relative to each other. An ordinary liquid is an example of the opposite, complete disorder, its atoms or ions seem to move in completely irregular fashion. These examples represent two extremes of the concept order-disorder. In nature, there are more subtle forms of order and a liquid crystal is an example of that. It can be well ordered in one dimension but completely disordered in another. De Gennes has generalized the description of order for media of this type and been able to see analogies with, e.g. magnetic and superconducting materials.

The discovery of the remarkable substances we now call liquid crystals was made by the Austrian botanist Friedrich Reinitzer slightly more than a hundred years ago. In studying plants, he found that a substance related to the cholesterol had two distinct melting points. At the lower temperature, the substance became liquid but opaque and at the higher temperature completely transparent. Earlier, similar properties had been found in stearin. The German physicist Otto Lehmann found that the material was completely uniform between these temperatures with properties characteristic of a liquid as well as a crystal. Therefore, he named it “liquid crystal”.

All of us have seen liquid crystals in the display of digital watches and pocket calculators. Most likely, we shall shortly see them also on the screen of our TV sets. Applications of this kind depend upon the unique optical properties of the liquid crystals and the fact that these can easily be changed, e.g. by an electric field.

It has been known for a long time that liquid crystals scatter light in an exceptional way, but all early explanations of this phenomenon failed. De Gennes found the explanation in the special way the molecules of a liquid crystal are ordered. One of the phases of a liquid crystal, called nematic, can be compared with a ferromagnet, where the atoms, which are themselves tiny magnets, are ordered so that they point in essentially the same direction – with slight variations. These variations follow a strict mathematical rule, which near the so-called critical temperature, where the magnet ceases to be magnetic, attains a very special form. In the liquid crystal the molecules are ordered in a similar way at every temperature, which explains its remarkable optical properties.

Another large field, where de Gennes has been very active, is that of polymer physics. A polymer consists of a large number of molecular fragments, monomers, which are linked together to form long chains or other structures. These molecules can be formed in a countless number of ways, giving the polymer materials a great variety of chemical and physical properties. We are quite familiar with some of the applications, which range from plastic bags to parts of automobiles and aircraft.

Also in these materials, de Gennes has found analogies with critical phenomena appearing in magnetic and superconducting materials. For instance, the size of the polymer in a solution increases by a certain power of the number of monomers, which is mathematically analogous to the behavior near a critical temperature of a magnet. This had led to the formulation of scaling laws, from which simple relations between different properties of polymers can be deduced. In this way, predictions can be made about unknown properties – predictions which later in many cases have been confirmed by experiments.

Major progress in science is often made by transfering knowledge from one discipline to another. Only few people have sufficiently deep insight and sufficient overview to carry out this process. De Gennes is definitely one of them.

Professor de Gennes,

You have been awarded the 1991 Nobel Prize in Physics for your outstanding contributions to the understanding of liquid crystals and polymers. It is my privilege to convey to you the heartiest congratulations of the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences, and I now ask you to receive the Prize from the hands of His Majesty the King.

What do they look like? ……..

|

|

||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||

|

Plastic, rubber, plexiglas, gels and textile fibres such as nylon and polyester are all synthetic materials made of polymer molecules.

|

A Frisbee is a mixture of crystalline (ordered) and amorphous (disordered) polymer structures. |

Each polymer molecule consists of linked basic units called monomers. The number of monomers in a chain can be very large, from thousands to several millions. The chains may be entangled like spaghetti (as above) or be ordered in crystalline formations.

|

The monomer is specific for every polymer and determines the name of the substance. A Frisbee is made of polyethylene which consists of linked ethylene (CH2CH2) monomers.

|

|||

|

|

||||||

|

If the polymer chain is long, its size can be described by simple proportion ratios called scaling laws: When the number of monomers N is doubled, the size is increased by the scaling factor 2v. The exponent v is universal in the sense that it is the same for all polymer chains although it depends on the polymer concentration. |

||||||

|

The snake-like (reptile-like) motion of an entangled polymer chain is explained by imaging that it is confined to a “tube” formed by adjacent chains. The reptation time t, the time needed for the chain to completely move out of the tube, can be obtained from simple scaling arguments. The reptation model leads to a smaller exponent (v= 3) than the measured one (v= 3.3) but it can nevertheless explain a number of phenomena and is very powerful in its simplicity. |

|

|||||

|

|

Are you familiar with “silly putty”, the strange substance which is both solid and liquid-like? If you pull it slowly in comparison with the reptation time, the material flows like a very viscous liquid. If you form it into a ball and strike it quickly, it bounces like rubber.

|

||||

|

Photo: L. Falk

|

Photo: L. Falk |

|||||

|

||||||

The Nobel Prize in Physics 1991

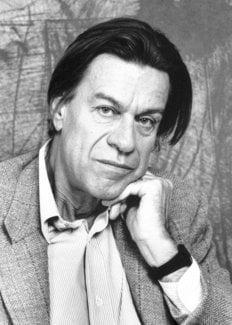

Pierre-Gilles de Gennes – Biographical

P. G. de Gennes was born in Paris, France, in 1932. He majored from the École Normale in 1955. From 1955 to 1959, he was a research engineer at the Atomic Energy Center (Saclay), working mainly on neutron scattering and magnetism, with advice from A. Herpin, A. Abragam and J. Friedel (PhD 1957). During 1959 he was a postdoctoral visitor with C. Kittel at Berkeley, and then served for 27 months in the French Navy. In 1961, he became assistant professor in Orsay and soon started the Orsay group on supraconductors. Later, 1968, he switched to liquid crystals. In 1971, he became Professor at the Collège de France, and was a participant of STRASACOL (a joint action of Strasbourg, Saclay and College de France) on polymer physics.

From 1980, he became interested in interfacial problems, in particular the dynamics of wetting. Recently, he has been concerned with the physical chemistry of adhesion.

P.G. de Gennes has received the Holweck Prize from the joint French and British Physical Society; the Ampere Prize, French Academy of Science; the gold medal from the French CNRS; the Matteuci Medal, Italian Academy; the Harvey Prize, Israel; the Wolf Prize, Israel; The Lorentz Medal, Dutch Academy of Arts and Sciences; and polymer awards from both APS and ACS.

He is a member of the French Academy of Sciences, the Dutch Academy of Arts and Sciences, the Royal Society, the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, and the National Academy of Sciences, USA.

This autobiography/biography was written at the time of the award and later published in the book series Les Prix Nobel/ Nobel Lectures/The Nobel Prizes. The information is sometimes updated with an addendum submitted by the Laureate.

Addendum, September 2005

From 1976 to 2002, P.-G. de Gennes was the director of the Ecole de Physique et Chimie (Paris). This is a center for the formation of research engineers in Physics, Chemistry (and, from de Gennes’ time, Biology). This place has been the base of Pierre and Marie Curie, Georges Claude, Paul Langevin, and recently of G. Charpak (after his retirement from CERN). It is a producer of small “start up” companies.

After receiving the Physics Prize in 1991, de Gennes decided to give talks on science, on innovation, and on common sense, to high school students. He visited around 200 high schools during 1992-1994. This story is summarized in a book (Les objets fragiles, Plon, Paris 1994).

Currently de Gennes is working at the Institut Curie (Paris), an interdisciplinary center and hospital on cancer research. He works on cellular adhesion and, more recently, on brain function.

Other recent books: Gouttes, bulles, perles et ondes (Belin, Paris 2003) with F. Brochard and D. Quéré. Petit point, a satirical book (Le Pommier, Paris 2003).

Pierre-Gilles de Gennes died on 18 May, 2007.

Copyright © The Nobel Foundation 2005