Transcript from an interview with the 2007 physics laureates

Interview with the 2007 Nobel Prize laureates in physics Albert Fert and Peter Grünberg, 6 December 2007. The interviewer is Adam Smith, Editor-in-Chief of Nobelprize.org.

Albert Fert, Peter Grünberg, welcome to this interview for Nobelprize.org. You are the co-recipients of the 2007 Nobel Prize in Physics and often the work for which the Nobel Prize in Physics is awarded is very remote from everyday life, but in this case the giant magnetoresistance effect that you discovered touches us on a daily basis because it forms the memory retrieval system in most personal computers. I wanted to start by asking whether it was with thoughts of this sort of application that you embarked on the research?

Albert Fert: For me of course the discovery it was obvious that would be applications, but the width of this application was difficult to predict, it depends on the markets and on all these aspects that for me I did not know, so I was supposing there would be applications but the large number cannot be predicted.

But it was with an interesting application that you began the research or the research was done with other things in mind?

Albert Fert: No, the research was not done for the application, research in nano physics follows these ideas and discover new landscapes and when there is a new landscape the knowledge of this other perspective to go into and so on, it’s not a direct way to applications.

Peter Grünberg: But in our case, I can say, for us also the main goal was not to develop a sensor but when we found this effect, then the context was also that at that time similar senses were already in preparation for the application in our disk drives for IBM for example, and that was the so-called anisotropic magnetoresistance effect, When we measured for the first time this new effect which was later called giant magnetoresistance then we saw that this new effect was really much stronger than the anisotropic effect which also was already in preparation to be used in a sensor in hard disk drives. Then it was rather obvious then to file a patent and the application was really promising that this could be used.

It sounds as if in your case there may have been more thought of application on looking for the effect?

Peter Grünberg: Not when at the time when we started the research, then we just hoped to do interesting physics and get a new effect and so on. Of course we expected that there could be an effect between the parallel and antiparallel alignment of the magnetisation that the resistivity could change, we expected that, but we didn’t think of an application at that time yet but when we saw it really happen then we were very much encouraged also to find a patent.

It would be interesting to ask what lead you to physics and fundamental physics research in the first place. How did you become a physicist?

Peter Grünberg: At one point in high school I realised that this is a very interesting field and that was when I was always wondering why do the planets orbit around the sun and why is that notion. I couldn’t explain it to me until I heard the explanation of Newton, that it is the attraction between masses which keeps the planet on their orbits. I was so impressed by this discovery for me, that I wanted to hear more about this, about all these things and then I became very much interested in physics. I was the age of about 15 years old and then it remained like this, I stayed interested in physics.

That’s a good role model to start with, Newton as your guiding light.

Peter Grünberg: Yes, definitely.

And how about you?

Albert Fert: At the university I was a good student in physics, but I was hesitating before going into research because I was so impressed by the accumulation of outstanding research by outstanding people before, and it is difficult to realise that there is some space for a new researcher. I was hesitating and then I realised there was space for young researchers, and so many seemed to find to discover and this is a crucial part of physics, that if you are going into research there are many discoveries expecting for you.

What was that moment when you discovered – to your own satisfaction – that there was space for you?

Albert Fert: At the beginning of my PhD I was hesitating, not so confident, but then during my PhD my subject was to test some predictions of Sir Nevill Mott, a British Nobel Prize, it was suggesting that the spin cool have an influence on the mobility of the electron in ferromagnetic material sensor. This was to be proved and so we conceived with my supervisors some tests and so I realised that after these experiments, after a good interpretation, a very precise interpretation of experiments, it was possible to derive a clear picture of this subject and this clear picture is in fact is a basic physical spintronic study and so even during my PhD I have realised that it was possible to find something new in this.

Was the possibility of finding something new allowed by the technology?

Albert Fert: At this time no, it was allowed more by the progress of the theory in the group of Professor Friedel in France, the theory of the electronic structures in metals, so the progress was made possible by the theory. In fact in during my PhD we had some concept more or less the same as the concept of the GMR in ternary alloys, but at this time it was not possible in 1970 to go beyond and to go directly to the general magnetoresistance because it was not possible to fabricate multilayers in very very thin layers. We had simply to put some ideas into the fridge and in the mid-1980s I saw that the progress of the technology made that it was possible fabricate very very thin layers, so I came back into this field that I had […] known and I saw also the good result of Peter in 1986 on the coupling between the layers and this led me rapidly to the discovery of the GMR.

So that’s leaping ahead to the point which …

Albert Fert: This is due to the encounter between previous basic physics, fundamental physics and the advance of the technology, and the meeting produced the discovery.

Yes, nano technology had advanced officially.

Albert Fert: Nano technology is a wonderful tool for us because we are now able to, not only to observe the nature but also to fabricate a new nature, new objects with novel properties.

Returning to that idea of space for research, do you think that is something that changes in physics research? Is there more or less space for researchers as you go through the decades, or are all young physicists, do you think, at any times faced with similar questions: is there going to be space for me? What do you tell your students about this?

Albert Fert: I would say there is more space now than there’s been before. Because of nano technology, this is a wonderful tool to create.

So it’s easier now?

Albert Fert: Not easier, it is another tool, an additional tool for the creation, not only the observation.

Peter Grünberg: My impression is if I come nowadays to industrial laboratories, there are not many people anymore. There used to be many people, I had many colleagues for example at Siemens company and also some people at IBM and also I saw in fact the same ones in Japan. There are now many empty labs where people used to do research before and now they have closed these sections, so they concentrate more on the application and engineering.

Where is the fundamental research being done, is less being done or is it being done elsewhere?

Peter Grünberg: Probably it’s just less being done. Even in the research centres we have problems with staff, to fix positions for staff, so that is also being refused.

Is this a consequence of the fact that fundamental physics research is becoming more expensive and therefore there is just less money to go round?

Peter Grünberg: I don’t know the reasons, I only see empty labs.

Albert Fert: Because this is one reason, because the research become very expensive, the technologies …

Peter Grünberg: Yes, preparation, facilities, other expenses, and you really very much depend on such facilities, to have to make good samples if you want to have reliable results because it’s very important to have really good samples.

Is one result of this that physics is becoming concentrated in centres which have the power to pay for this, is it becoming more focussed?

Albert Fert: Yes certainly, only big companies for the research in the industry and also in some countries … I remember twenty years ago the research in South America, in small countries, was improving and catching up in research, but now the gap become larger. Because now it is only possible to make good research in some country with a very high technology and a lot of money, except maybe that there will be some country that will catch the others, China, India, Korea.

Does that provide then a nice flow of good young physicists from these countries coming in to the …?

Albert Fert: Yes, there is a lot of them, but there are also good labs in these countries, these new countries.

Peter Grünberg: Yes, for example there is an interesting tendency with China. About ten years ago when somebody applied from China to come to your lab and work there for some time you would expect that he never wants to go back to China, but now that has changed. Many many Chinese come and stay in Europe, probably also United States for some time but then they’re eager also to go back and there are also good positions for them, so definitely the situation in these countries is improving.

In your own careers were there particular people who made an enormous difference to the direction you took, who gave you guidance in a special way?

Peter Grünberg: I always worked with students and of course they are mostly newcomers or one can say, all the time newcomers in the field, so from that point of view you have to take the lead really, because you are continuously in some field and develop that and the students adjust to your subject and we discuss, but you have to take the lead.

But as a student yourself was there anybody who made a vast difference to your path, your choice of what you were going to work on or the way you worked on it? Did you have a mentor that was particularly important?

Peter Grünberg: Yes definitely, I had a mentor who defined the subject of my theses and then I worked on this. I still have contact with my mentor and hopefully he will also be here, come to the ceremony. Then I had many discussions with him while I was working on the subject, so one can say that, yes.

How about your professor Fert?

Albert Fert: My good luck during my PhD was that I was in the laboratory with a good mixing of experimentalists and theorists and the concept was to discuss with a foreign […]/ like me […] so I learned on both sides and this has been an advantage for me during my career. I was always able to proceed from experimental theory and some of my more cited papers are in theory, and so I think this was an advantage for me. Now I see that with the difficulty of the technology it’s more difficult for young people to be good on both sides, theory and experiments, so it was a good beginning.

Would you say you enjoy one more than the other – theory than experiment?

Albert Fert: No, I enjoy both, I enjoy physics in general, but it’s very gratifying to not only understand the experiment but at the same time to understand, deploy, the theory and to have a general view on both aspects.

How about you?

Peter Grünberg: That was a very similar situation for me too. Before I came into this transport phenomena and magnetoresistance, I studied a lot spinwaves and magnetic excitations in the […] structures. Then it was a very exciting experience for me that after some time the behaviour to do these calculations and predict such spinwaves and the frequencies of such spinwaves as a function of magnetic field or the orientation or in the field when you have anti-parallel alignment. Then at one point we were able to do a calculation simply by turning the one plus sign into a minus sign for the anti-parallel magnetisation in line and it was a very exciting moment for me to see that also in the experiment to see finally also the experiment shows that a calculation was really right, because when you do the calculation you never know whether you’ve made some mistakes or overlooked some boundary condition which does not allow to do this particular case because to violate some other laws. We were not sure but when we finally found those calculations correct from the experiment and this is a very exciting moment.

There must be rare moments when everything comes together, and the experiment proves what you thought. Is that the best bit of being a physicist, having these things happen, or is the best bit just being a physicist full stop?

Albert Fert: No, the marvel of physic is that for example you can start from pure abstract conscription in your mind and then is very gratifying and amazing to see that they become a concrete reality in the experiments and even more a concrete reality in the everyday life for, for the GMR. It is something fantastic to see that – something purely abstract become a reality of the life, that you see in the streets, in the shops. When you see for example a computer, we know that there is a hard disc working with something that we had in your mind 20 years ago and that this purely abstract thing became a device.

I wanted to ask you how it feels to spore the technology that is so widely used. It must be tremendously exciting to see it in use everywhere.

Albert Fert: Yes, amazing. It’s marvellous to see, that is the power of science, we see the power. I’ve been convinced, I was hesitating at the beginning of my career of what it could do, now I am convinced that science works.

Peter Grünberg: I am also very happy about the fact that this goes into an application that can be used for something. One can do very fine research, but then you always have to ask yourself is it really something, do we really learn something very new about nature and all these things, and in most of the case – when you are very critical – you say well, this is all in the old framework somehow, it’s not a complete jump into something which was completely unknown before, mostly not the case. Therefore, it’s very rewarding and satisfying if you have also an application for the kind of research you are doing.

Albert Fert: This is not unique for GMR. GMR gives a good example, an outstanding example, but in our career this happen several times and not for so large applications but for some less known discovery, but it’s exciting in any case, even for small discoveries. When you discover that you have predicted is a reality.

Let’s talk about GMR a little bit, but it’s quantum mechanics, so it’s difficult to comprehend. The idea that a magnetic field could affect a current was observed 150 years by Lord Kelvin. The magnitude of that effect was found to be possibly very much greater, or you discovered a very much greater effect than he discovered in the 1980s when you made your discoveries. Basically it’s to do with underlined or aligned electron spin, impeding current, and the model that I have been able to comprehend myself is the analogy with polarisers, that if electron spin – or the magnetic glare – is the polariser, crossed polarisers will impede for the flow of current, align polarisers will allow the flow of current, but I’d love to invite you to do a better description of GMR than that yourselves.

Albert Fert: The general idea of spin really is the general concept of spin […] is to put on the wheels on the electrons, this thin layer of ferromagnetic materials and to use the action of this thin layer of materials on the motion of the electrons. This is applied in GMR and in any of all the other effect of spintronics, this new image of polariser. He plays a magnetic field by something stronger that the electron can feel inside the ferromagnetic material you see. This corresponds to a multiplication by a very large factor of the affecting field acting on the spins.

Peter Grünberg: The picture of the polariser I think would have to be modified a little in that. In this picture of the polarisers the electrons move parallel to the polarisers, there is not a cross polariser situation which would apply for electrons which go mainly from one field to the other across the interlayer. This takes place too, but in that picture of the polariser our electrons move parallel to the polarisers and yet, since they travel back and forth during that drift after the current, there is some effect which could be also described by polarising effect, but the main motion of the electrons so to say in plain in parallel to the polariser in this picture as you described.

Albert Fert: But it was the first stage of spintronics, so it was, but in the new development of spintronics now, for a more efficiency the electrons are going through the magnetic layer.

So now the model becomes more appropriate.

Albert Fert: But it was not possible to do that technology […] in the beginning. The GMR was a […] way to approach the problem.

I suppose it doesn’t really matter if people understand how it works but what is interesting to them is to know how it will be used. We know about memory retrieval in hard disk drives, but the potential for GMR’s application is much wider than that. Would you like to speak a little about how you see GMR being used in the future?

Peter Grünberg: One application, and in fact I must say I didn’t even know about that application really, that came up doing all these discussions after the announcement of the Nobel Prize, people came to me: Oh, it is used in iPods, mp3 players, I didn’t know about that. So this is a very important application, I think, because these players are used everywhere, a huge application. It is being used, it will further being used, it will still be improved, but of course at some point probably there will be no more improvement, everything has physic limits. The density on hard disk drives has certain physic limits but then we will continue on a high level. But other applications of this magnetoresistance effect and that might be used one day in magnetic random access memories. This is in development now in the industry to achieve this.

This development, that relies on using current to induce a magnetisation rather than magnetisation to a changing current.

Albert Fert: This is a new development of spintronics because you can consider for the application of GMR first, so hard discs is the extension of the hard disc solution to mobile electronics, iPods, cameras and also medical applications. I have seen recently the application of GMR to encephalography, to the detection of the magnetic field generated by the brain. This is one side of the application, direct application of GMR, but the main result of GMR that is kicked off the theory of spintronics, a field looking for all the property related to the influences of the spin […] electrons. In spintronics there would be many other effects and is promising many other applications, for example … mainly walking on, under a type of effect called spin transfer for generation of radio waves, of micro waves, so this field of spin electronics has no real application not at all in the technology of computers but mainly on telecommunications. In fact now spintronics is expanding in many directions and with applications in many fields.

So this is for making nano scale transmitters?

Albert Fert: Yes, emitters, oscillators. In spin transfer experiments one manipulates the magnetisation, a magnet, without applying the magnetic field like traditionally, but by sort of transfusion of spins from an electrical current and this can be used to reverse the magnet. It is the contrary of the GMR, then one adds with the current on the magnet and also to generate oscillations and generate radio waves, microwaves, so this paves the way for many different applications.

This begs the question for me, when people come to work with you now on GMR and spintronics …

Albert Fert: GMR is passed.

GMR is finished, ok, GMR is done. When they come to work with you on spintronics and the further elaborations …

Peter Grünberg:: We have not seen that yet, I protest. GMR is not … There are still a lot of questions and interesting …

Albert Fert: There’s still questions but they are not so exciting now as new directions …

Peter Grünberg: I just wanted to make that comment.

When students come to work with you, because they have already seen the application potential of this, do you find that they are very focussed on application more than they should be, do you think?

Albert Fert: It depends on the students I guess, some are more attracted by the fundamental aspects, some now are attracted by the application, so there are different type of students.

So you still have the diversity, ok. It’s been very interesting talking to you, thank you very much indeed. I did want to ask one last question which was how the last two months have been. It’s a sudden whirlwind that starts when you hear the news that you have been awarded the prize. How have you found the last couple of months?

Peter Grünberg: Partly very tiring and I’ve had so many interviews, on the other hand it’s also nice to get some applause, it’s always nice. You are confirmed that this was the right way to do something and we have arrived at something, so a very good situation.

Albert Fert: There was a storm, there’s a big storm: interviews, many questions, conferences and also some responsibility, because now the people ask us for our advice on the reform of the research in our country and how to change the management of the universities, so new responsibilities. Many solicitations and I suppose we have learned to filter these things and to select only the most interesting requirements and requests.

Yes, I imagine you get very good at prioritisation.

Albert Fert: Yes, prioritisation.

Peter Grünberg: Many doors open which have been closed like now there is a magic stick, they are suddenly open. You are supported.

I shall leave you to your open doors that follow this interview. It was a great pleasure to talk to you. Peter Grünberg, Albert Fert, thank you very much indeed.

Albert Fert: Thank you.

Peter Grünberg: Thank you too.

Did you find any typos in this text? We would appreciate your assistance in identifying any errors and to let us know. Thank you for taking the time to report the errors by sending us an e-mail.

Peter Grünberg – Facts

Peter Grünberg – Biographical

A typical question I am often asked as a Nobel Laureate in physics is “what brought you to physics?” I am not sure but I do know that in school in geography when looking at the presentations of the planets orbiting around the sun I asked myself: “What is the reason for this strange behavior?” It was a real revelation when my physics teacher Mr. Röderer explained to me that this is caused by the balance of the attraction between masses and centrifugal forces. This roused my enthusiasm and whetted my appetite. Still, during my last few years in high school, I spent more time with sports, boy scouting, alpinism, music etc. so my performance in school was reasonable but not more.

Perhaps in this context, it might be of interest to know that my father held a diploma in mechanical engineering from the Technical University of Bruenn (Cechia), and worked for the Skoda factory in Pilsen designing locomotives. He died during the last days of the war, so after our expatriation to the western part of Germany, my mother was left alone to take care of her two children, namely my two-year older sister and myself.

At the age of 19, I started to study physics at the University of Frankfurt and changed to the Technical University of Darmstadt three years later. I finished my diploma thesis there at the age of 26 and my PhD thesis at the age of 29. In both theses, I applied optical spectroscopy to determine crystal field split energy levels of rare earth ions in garnets. The director of the institute was Professor K. H. Hellwege. As I did a lot of computational work for the experiments, he used to say to me when he met me in the corridors: “Above all mathematics, don’t neglect the physical background” which he called “Physikalischer Hosenboden” (lit. “physical bottom”). This must have made a lasting impression on me because I have a strong desire to explain new phenomena which I come across in simple physical pictures and do not feel comfortable with mathematical formalism alone. Today, I would like to pass this attitude on. In computer simulations in particular we would get lost in an abundance of results if we did not maintain a critical view for the source of the effects. This is especially true for phenomena caused by a constructive or destructive interaction of various mechanisms. My direct supervisor for my thesis work was Prof. Stefan Hüfner.

The topics of garnets and crystal fields also brought me to the laboratory of Prof. A. Koningstein in Ottawa, Canada, where I worked as a postdoc for a little less than three years. As was the case until then my goal remained the determination of crystal fields, but here I used the electronic Raman effect to determine the energy levels experimentally. Since Raman scattering is mainly caused by the optical phonons, these were also included in my investigations. A photo of me at the age of 33 is shown in Figure 1.

In 1972, I was offered a position as a research scientist at the newly founded Institute for Magnetism at the research centre in Jülich. The director was Prof. Werner Zinn. His picture (marked with WZ) is included in the group photo of Figure 2. He was mainly interested in investigating the model magnetic semiconductors EuO and EuS. I also started to work on these compounds, applying optical absorption spectroscopy as well as Raman scattering (RS) from phonons. The RS experiments were performed at the Max Planck Institute for Solid State Physics in Stuttgart in the group headed by M. Cardona. My partner in Stuttgart was Gernot Güntherodt (marked GG in Figure 2) with whom I explored the magnon phonon interaction in EuO and EuS.

RS often causes a problem if we want to observe scattering with small frequency shifts below about 30 GHz (corresponding to 1 cm-1). This is the domain of Brillouin lightscattering spectroscopy (BLS), where instead of a grating monochromator as in RS, a Fabry Perot interferometer is used as the dispersive element. In the early 1970s in BLS instrumentation, an interesting development occurred due to the pioneering work of John Sandercock in Zürich. He invented the multipass operation, and later on, showed how two multipass interferometers could be used in tandem. Following this example we assembled our own setup, namely a triple-pass spectrometer without tandem operation. A schematic is shown in Figure 1 of [1]. John not only pioneered the experimental technique, he also demonstrated the improvement with the first BLS measurements of various phenomena in solid state physics. This work had a great impact on ours. At the same time, he established his own company. Researcher, inventor, entrepreneur, salesman – all at the same time: following in the footsteps of Alfred Nobel! I have the greatest respect for such people. He has since been awarded various prices, of which the David Richardson Medal of the Optical Society of America (2005) is the latest.

One of his experiments grabbed our attention in particular. It was the first measurement of acoustic spinwaves in Yttrium Iron Garnet (YIG) and there fore the first time that acoustic spinwaves were measured in ferro- or ferrimagnets by means of LS. This result encouraged us to try the same experiment with EuO. However, as this compound only orders ferromagnetically below 60 K, cooling was necessary. Fortunately, a cryostat with a superconducting magnet was available from the optical experiments, so it was brought to the BLS setup. Before long, we were able to detect BLS from the bulk spinwaves. Additional scattering with a very strong Stokes/anti-Stokes (S/aS) anomaly could finally be identified. This was due to a spinwave propagating along the surface in one direction only and not the opposite. The successful observation of spinwaves in the bulk and at the surface of EuO is described in [1]. It has the character of an anecdote that the clue for the interpretation of a certain peak, caused by a surface spinwave, was uncovered when the experimental setup broke down and had to be repaired.

Further important results in this context were obtained by John Sandercock together with Wolfram Wettling. They measured the bulk and surface spinwaves from ferromagnetic metals in the shape of platelets with thicknesses of the order of mm. Standing spinwaves in thin films with thick nesses of the order of 100 nm or less were seen by Marcus Grimsditch and Alex Malozemoff (AM in Figure 2) for the first time. References to all of this work can be found in reference 2 of [1]. From this period, I also would like to mention fruitful contacts with Burkhard Hillebrands (BHi in Figure 2), who later extended BLS to thin film structures with lateral confinement.

Often in experiments with light, strong metallic optical absorption is considered a disadvantage because it significantly reduces the interaction volume. In LS experiments on standing spinwaves, however, it turns out to be of advantage because the wavevector of the incident light is smeared out due to strong optical absorption. As a result, a whole band of wavevectors is available to fulfill total momentum conservation, which is one of the required experimental conditions in BLS. A BLS spectrum from spinwaves showing the surface – and a standing mode is displayed in Figure 2 of [1]. To emphasise the last point: the standing modes are only observed because the wavevector of the incident light is sufficiently smeared out due to strong metallic optical absorption. In contrast, unpinned standing modes with antinodes at the surfaces are not seen by microwave absorption because the total precessing moment cancels out. This aspect was later discussed by John Cochran and Bret Heinrich. Both are seen in Figure 2 on the upper right-hand side, marked JC and BH, respectively. Next, we extended the LS investigations of spinwaves to multilayered structures. We concentrated on “magnetic double layers” i.e. two ferromagnetic films separated by a non ferromagnetic interlayer. One main interest was the coupling of DE modes to the collective dipolar modes of the structure. The most important results of these investigations are summarized in Figure 3 of [1].

At this point, I wish to mention that my meanwhile permanent staff position in a government-funded research laboratory allowed me to make long-term planning and to build up equipment for sophisticated sample preparation. At that time, such components were only partly available on the market. In this endeavour, I was assisted by my technician Reinert Schreiber who designed, assembled and operated the machine to prepare the samples. A particular feature which he installed was the “wedge technique”. It provides the possibility of making thin-film samples with increasing thickness from one end to the other. Later, this turned out to be very helpful for the study of thickness dependencies. A picture of Reinert performing some leak testing is shown in Figure 3.

I did the first calculations on the dipolar-coupled DE modes, as displayed in Figure 3 of [1] myself. The extension to multilayers was done together with my colleague K. Mika from the mathematical department of our institute. Knowledge of the effect of dipolar coupling on the spinwave frequencies and the experimental result on standing modes was sufficient to be able to qualitatively predict their behaviour under the effect of ferro- or antiferromagnetic exchange coupling. This is explained in [1] in the context of Figure 3 and Figure 4.

Let us return to the “trilayer” or “magnetic double layer” structure as displayed in Figure 3 of [1]. It explains how F and AF coupling can be determined qualitatively from the frequency shift of the optic mode. What we observed at that time were only frequency upshifts. According to Figure 4 of [1], the coupling then is ferromagnetic.

In the early 1980s, it was believed that there were mainly two mechanisms that explained coupling. These were pinhole coupling via magnetic bridges across holes in the interlayers and “orange peel” or Néel-type coupling due to meandering interlayers. Remagnetization curves which can reveal antiferromagnetic-type coupling yield no information when the coupling is ferromagnetic. For these reasons, the situation concerning coupling was still rather uncertain in the early ’80s. Under these conditions, we started a systematic search using the spinwave method. We also concentrated on the more unique case of antiferromagnetic (AF) type coupling, trying to find an example.

While on a year’s sabbatical leave at Argonne National Laboratory in the U.S. as a guest of Mervin Brodsky, this search was finally successful. We detected AF coupling in Fe/Cr/Fe structures on cleaved substrates of rocksalt. Details are found in [1]. Two of the colleagues I met at Argonne, with whom I worked on other topics namely Ivan Schuller (IS) and Sam Bader (SB), can also be seen in Figure 2. When I came back from the U.S., I continued working on the reproducibility of the effect, now using also epipolished GaAs substrates. At that time, Jozef Barnas, a theoretician from Poznan in Poland, joined my group and we started to work on a quantitative theory of the effect of coupling on spinwaves. A photo of Jozef is shown in Figure 4, and some results of our joint efforts have been published in ref. 2 of [1].

Furthermore, at that time, anisotropic magnetoresistance (AMR) was widely discussed by the community for applications in sensors for hard disk drives. So “something was already in the air” regarding MR effects and we decided to complement the available experimental techniques with magnetoresistance. Jean Pierre Renard (JR in Figure 2) had found an effect which later on turned out to be related to GMR. In our laboratory, Gaby Binasch installed the equipment during her diploma work and did the first measurements on permalloy films. Since Reinert Schreiber was now also able to make AF coupled Fe/Cr/Fe structures in a form suitable for measuring of electrical resistivity, GMR was seen before long as discussed in [1] and published in ref. 8 thereof. Gaby finished her thesis and received her diploma in physics (equivalent to masters). After this, she left Jülich for an interesting job in industry. She can be seen in Figure 5 at the celebration for her diploma.

Before I come back to GMR, let me add a few more details on coupling. As mentioned in [1], at the same time that we were working on Fe/Cr/Fe, other groups found similar phenomena for rare earth layers (Gd, Y) separated by Y layers. An RKKY-type mechanism was proposed by Yako Yafet (marked YY in Figure 2) as an explanation. Even oscillatory behaviour as a function of the interlayer (Y) thickness had already been reported. However, it seems that only after the discovery of GMR, coupling per se also received general attention. And sure there were many results and surprises. The RKKY-type mechanism was applied to structures with magnetic 3d-transition metals by George Mathon (GM in Figure 2), David Edwards and Patrick Bruno (PB in Figure 2). With the permission of the colleagues involved, I may at this point tell the following anecdote. In the course of his search for AF couplings Stuart Parkin from IBM San Jose (SP in Figure 2) had found it also for sputtered Co films with [111] texture interspaced by Cu. The Dutch group from Philips Eindhoven established oscillatory coupling for this system also for epitaxial growth with [100] orientation. Bill Egelhoff from NIST in Gaithersburg, well-known for very fine work in epitaxy, however, reproached vigorously. I still remember a MRS meeting in San Francisco where he defended his point. Then Professor Gradmann (UG in Figure 2) from Clausthal University in Germany stood up and said: “Bill I think I know what happened. Your samples are too good. You have very fine surfaces which nucleate antiphase domains that give large angle grain boundaries between the islands. Then you can get diffusion of Co along the boundaries and the formation of magnetic bridges. The resulting F-coupling swamps any possible AF coupling.” Bill Egelhoff responded simply: “I like that”. Indeed, somewhat later, Jürgen Kirschner (JK in Figure 2) and his group from Freie Universität in Berlin added further evidence to this case by showing that grain boundary formation comes from the usual competition between ABABA.. and ABCABC… type stacking for hcp type structures along [111].

Coming back to Bill Egelhoff, it has also to be mentioned that he used oxygen as a surfactant to set the record values for GMR of 25% in the simple trilayer structures of Co and Cu and also dual spinvalves with two Cu interlayers. In multilayered structures, of course, the effect is much stronger.

This example demonstrates again that coupling can change drastically with growth, which makes comparison with theory ambiguous. Then how do we know that current theories on this phenomenon as proposed for the first time by Yako Yafet are in essence correct? An important contribution to this comes from Bob Celotta’s group at NIST. They grew trilayer-type samples, where one magnetic layer was replaced by a single crystal Fe whisker, which at the same time is used as a substrate. For the interlayer, various materials were chosen with an emphasis on good matching to Fe. Coupling is seen via magnetic domains, which are made visible using SEMPA. These indeed superb and celebrated experiments left no doubt that theories based on the RKKY interaction predict oscillatory coupling correctly. In real cases, however, the coupling could still be good for many surprises, as is clear from the anecdote above.

Another phenomenon which also finally turned out to be related to growth is that of 90° type coupling. This was proposed by A. Hubert and his group as the reason for special magnetic domain structures occurring in samples with wedge-shaped interlayers. Alex Hubert (AH) and his coworker Rudi Schäfer (RS) can also be seen in Figure 2.

For the size of the GMR effect, there is a large difference between trilayers and multilayers, as shown in Figure 9 of [1]. This has been known since GMR was announced publically for the first time at the ICMFS in Le Creusot in France, organized by Irena Puchalska (IR) and Horst Hoffmann (HH). I also met Albert Fert there for the first time (as he attended the conference but was not in the original group photo, I added his photo (AF) on the right-hand side of Figure 2). After we had compared our results and came to the conclusion that we had seen the same effect and thus confirmed it to each other, we were ready for a glass of red wine from Burgundy. We were not the only ones who enjoyed that conference. A group of talented musicians among the participants entertained us with piano concertos (Alex Malozemoff-AM and Jaques Miltat-JM), Urich Gradmann (UG) and Mrs. Yafet on the violin and finally Klaus Rohrmann (KR) with a solo on a water hose. The arrival of GMR was adequately celebrated indeed!

When I returned home from the conference in Le Creusot, I was in a very fortunate situation that I had two excellent theoreticians as visiting scientists in Jülich. A picture of Jozef Barnas has already been shown in Figure 4, a passport photo of Bob Camley is shown in Figure 6. I now had both previous collaborators on spinwaves together again in Jülich, but now the new exciting topic was the GMR effect. Before long, they had worked out a theory based on Boltzmann’s diffusion equation for the evaluation of the GMR experiments which became known as the Camley-Barnas model.

The title of my Nobel lecture includes the term “beyond”. The team with whom I obtained most of the results “beyond” can be seen in Figure 7. We conducted much work on Si interlayers, where we found very strong coupling but disappointingly weak tunnel magnetoresistance. We also started on “current-induced magnetic switching” (CIMS) as invented by John Slonczewski and Luc Berger. John and his wife Ester stayed with me various times in Jülich. My successor as group leader, Daniel Bürgler, can be seen in the middle of Figure 7 (3rd from the left).

In 1998, I was invited by Hiroyasu Fujimori (HF in Figure 2 and 3rd from left in Figure 8) to come to Sendai, Japan, for 6 months. During this stay, I also spent two months in Tsukuba as a guest of Yoshishige Suzuki. A group photo with my collaborators in Sendai is shown in Figure 8. Of these, Koki Takanashi in 1995 had spent a year in Jülich as a postdoc. Terunobu Miyazaki is one of the inventors of tunnel magnetoresistance (TMR) at room temperature and with Akira Yoshihara I worked on BLS from spinwaves.

I officially retired in 2004, but kept a desk and some office space in the research centre within the Institute for Electronic Properties headed by Claus Schneider (CS in Figure 2). In this way, I was able to maintain my contacts with the scientific community, of which I wish to mention only as example a visit to Vladimir Ustinov (VU in Figure 2) in Ekaterinenburg. Now – as a result of being awarded this great Prize, I have also received a new contract from my employer in the form of a “Helmholtz professorship”. As a result, I call myself jokingly a “re-entrant magnetician”. I should explain to the non-expert that re-entrant magnetism is where magnetism disappears as a function of some parameter (like pressure or temperature) at a certain value but comes back at another value. Obviously, the relevant parameter in my case is age!

I would like to add a remark on my religious believes. Brought up rather conservative catholique I see religions now more or less in the spirit of Lessing’s (German dramatist 1729-1781) ring parabola which I would top by saying that – not only does nobody know which is the right ring (standing for religion) – but there indeed is no such thing as a right or false ring. Per se they are all equivalent. What really counts is how religions are practised, for example, with tolerance. And yet I believe that there is more than what we see, hear etc., or can detect with instruments. But it is a feeling borne out of many details of my personal experience and therefore impossible to share or communicate.

References

[1] Nobel Lecture of P. Grünberg.

This autobiography/biography was written at the time of the award and later published in the book series Les Prix Nobel/ Nobel Lectures/The Nobel Prizes. The information is sometimes updated with an addendum submitted by the Laureate.

Peter Grünberg died on 9 April 2018.

Speed read: The giant within small devices

Lying at the heart of the computer which you are using to read this article is a memory retrieval system based on the discoveries for which the 2007 Nobel Prize in Physics was awarded to Albert Fert and Peter Grünberg. They discovered, quite independently, a new way of using magnetism to control the flow of electrical current through sandwiches of metals built at the nanotechnology scale.

150 years ago, William Thomson observed very small changes in the electrical properties of metals when they were placed in a magnetic field, a phenomenon he named ‘Magnetoresistance’. In due course, his finding found application, magnetically-induced current fluctuations becoming the underlying principle for reading computer memories. Then, in 1988, Fert and Grünberg, working with specially-constructed stacks made from alternating layers of very thinly-spread iron and chromium, unexpectedly discovered that they could use magnetic fields to evoke much greater increases in electrical resistance than Thomson, or anyone since, had observed. Recognizing the novelty of the effect, Fert named it ‘Giant magnetoresistance’, and it was only a few years before the improvements, and the miniaturization, it offered led to its adoption in favour of classical magnetoresistance.

Giant magnetoresistance is essentially a quantum mechanical effect depending on the property of electron spin. Using an applied magnetic field to cause the electrons belonging to atoms in alternate metal layers to adopt opposite spins results in a reduction in the passage of electric current, in a similar fashion to the way that crossed polarizing filters block the passage of sunlight. When, however, magnetic fields are used to align the electron spins in different layers, current passes more easily, just as light passes through polarizers aligned in the same direction.

The application of this discovery has been rapid and wide-ranging, dramatically improving information storage capacity in many devices, from computers to car brakes. And while quietly pervading the technology behind our daily lives, the principles of giant magnetoresistance are now being used to tackle problems in wider fields, for instance in the selective separation of genetic material.

Peter Grünberg – Nobel Lecture

Peter Grünberg held his Nobel Lecture on 8 December 2007, at Aula Magna, Stockholm University. He was introduced by Professor Per Carlson, Chairman of the Nobel Committee for Physics.

Lecture Slides

Pdf 4.30 MB

Read the Nobel Lecture

Pdf 389kB

Albert Fert – Banquet speech

Albert Fert’s speech at the Nobel Banquet in the Stockholm City Hall, 10 December 2007.

Your Majesties, your Royal Highnesses, ladies and gentlemen,

it is a great honour for Peter Grünberg and me to accept the Nobel Prize. We express our gratitude to the Royal Academy of Sciences and the Nobel Foundation. We want also to acknowledge the outstanding contributions to our work of many brilliant coworkers. I thank my coworkers, especially and directly those who are at this banquet today, I thank also my first guides in physics, my father, who was a physicist, a very acute physicist, Jacques Friedel and Ian Campbell, my guides at the time of my PhD, and, last but not least, I thank the partner for everything in my life, Marie-Josée, my wife.

I want also to tell you how another person, from Sweden, played certainly an important role for my orientation. When I was at the university, I liked physics, but I liked the arts too, I was a good photographer, I liked cinema, I wrote and I shot a film. My main inspiration was Ingmar Bergman, my god was Bergman. I remember trying to express the feelings I wanted to express by black and white close-up and slow panning shots, inspired by the first films of Bergman, Sommarlek, Sommaren med Monika, Smultronstället. But, when I saw my film, it was not at all expressing what I wanted to express, and I realized that, unfortunately, I was at light years from what I had seen in Bergman’s films. But I could remember that I had some skills in physics, I began a PhD and I found that the research can be a very creative work too. The discovery of new and beautiful landscapes in the field of knowledge was also fascinating, and this led me to be here today, partly thanks to the inaccessibility of the genius of Ingmar Bergman.

On my way, I have discovered the beauty of sciences. It is amazing for a researcher to see the product of his ideas, of purely abstract constructions with electrons and spins, becoming a concrete reality of the everyday life. For Peter and me, it is amazing to realize that some of our ideas have led to applications we use everyday in our computer, something which is also useful to many people. Of course we have not been alone in this adventure. Spintronics has become a fruitful field of research thanks to the contributions of a very active international community and we are very pleased to acknowledge this collective contribution to the work which is recognized today.

Albert Fert – Prize presentation

Watch a video clip of the 2007 Nobel Laureate in Physics, Albert Fert, receiving his Nobel Prize medal and diploma during the Nobel Prize Award Ceremony at the Concert Hall in Stockholm, Sweden, on 10 December 2007.

Peter Grünberg – Prize presentation

Watch a video clip of the 2007 Nobel Laureate in Physics, Peter Grünberg, receiving his Nobel Prize medal and diploma during the Nobel Prize Award Ceremony at the Concert Hall in Stockholm, Sweden, on 10 December 2007.

Q&A with Peter Grünberg, October 2007

After the 2007 Nobel Prize announcements, visitors to Nobelprize.org had the possibility to submit questions to the 2007 Nobel Laureates. Here, Peter Grünberg answers a selection of the questions.

Question: Who, or what, inspired you to enter your field of achievement?

Bobby Cerini, age 34, Australia

Answer: Myself, and my desire to do something significant. To some extent it was also against the plan of my supervisor, but he was tolerant enough to finally accept my activities.

Question: In one word, can you describe your reaction when you knew you had been awarded the Nobel Prize?

Young eager student, age 13, United States

Answer: Well I knew that I had been traded as possible candidate years before. So the reaction was more like: “Ah, finally”.

Question: Has there ever been a time in your life and/or work when you have doubted what you were doing to the point that you seriously considered abandoning said work? Anna, age 16, United Kingdom

Answer: My research topics gradually changed all the time but I tried always to build upon knowledge that I had gained before. So for me it was very important to have continuity. I wanted to do good work which could be published in well-reputed journals. When I started my research I didn’t expect that finally there would be the Giant Magnetoresistance effect. It was only when we had found antiferromagnetic type coupling two years before the discovery of GMR that we thought this could be possible and installed the necessary equipment.

Question: First of all, congratulations! What will you do with the prize money? You have done something extraordinary to win the Nobel Prize – perhaps you deserve to spend it all on yourself!

Scott MacLeod, age 38, United States

Answer: Having been honoured so high on an international podium I see this Prize money as an obligation to be internationally available. The requests and demands are manifold. Believe me, it is not a comfortable life and often I have expenses which I pay for from my own pocket. So I see being a Laureate as a job which is paid adequately from the prize money.

Question: At any given time you obviously have several questions in your mind that you want to find answers for in your research. How do you choose which ones to pursue first and spend most of your efforts on?

Nurmukhammad Yusupov, age 30, Uzbekistan

Answer: Yes, indeed I have had other ideas that could have turned out to be of importance or even a breakthrough. Whenever I have such an idea I make a corresponding note on the last pages of my notebook. But my nature is to concentrate only on one thing at a time. Of course, when you start to have doubts that your project will be successful you play with other ideas also, and then I consult my notebook. Before giving up one should carefully test out all possibilities, but also not fall into stubbornness.

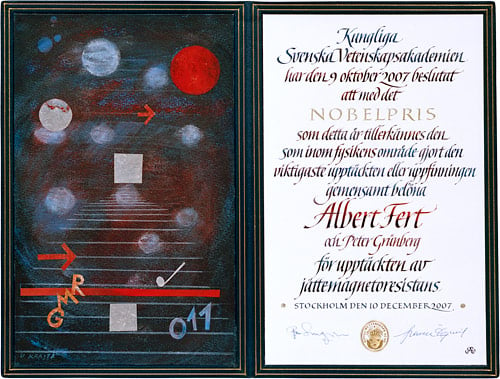

Albert Fert – Nobel diploma

Copyright © The Nobel Foundation 2007

Artist: Ulla Kraitz

Calligrapher: Annika Rücker

Photo reproduction: Fredrika Berghult