Gerhart Hauptmann – Nobel Lecture

Gerhart Hauptmann did not deliver a Nobel Lecture.

Gerhart Hauptmann – Banquet speech

Gerhart Hauptmann’s speech at the Nobel Banquet in Stockholm, December 10, 1912

(in German)

Als Empfänger des diesjährigen litterarischen Nobelpreises danke ich Ihnen für die warmen und freundlichen Worte, die auch an mich gerichtet worden sind. Sie dürfen überzeugt sein, dass ich und mit mir meine Nation die Ehre völlig verstehen und schätzen, die mir widerfahren ist. Der Nobeltag ist zu einer Kulturangelegenheit des ganzen Erdballs geworden, und der grossartige Stifter hat auf unübersehbare Zeiten hin seinen Namen mit dem Kulturleben aller Nationen verknüpft. Hervorragende Männer aus allen Himmelsstrichen werden wie heute noch in späten Zeiten den Namen Nobel mit ähnlichen Gefühlen aussprechen, wie Menschen in früheren Zeiten ihren Schutzpatron nannten, dessen hilfreiche Kraft nicht bezweifelt werden konnte. Und seine Denkmünze wird in Familien unter allen Völkern von Geschlecht zu Geschlecht vererbt und in Ehren gehalten werden.

Es ziemt sich daher, dass ich diesem grossen Donator den Tribut von Ehrfurcht zolle, der sich ständig erneut, und nach ihm der ganzen schwedischen Nation, die diesen Mann hervorgebracht hat, und die so getreu sein humanitäres Testament verwaltet. Und dabei habe ich auch den Männern zu danken, deren aufopfernde Lynkeusarbeit dazu ausersehen ist, über die Kulturarbeit der ganzen Erde zu wachen, auf dass gute Keime aufspriessen mögen und das Unkraut vermindert werde.

Ich danke Ihnen und wünsche, dass Sie nie in der segensreichsten aller Tätigkeit ermüden und nie wirklich reiche Ernten vermissen mögen.

Und nun trinke ich darauf, dass das Ideal, das der Stiftung zugrunde liegt, seiner Verwirklichung immer näher gefuhrt werden möge, ich meine das Ideal des Weltfriedens, das ja das höchste Ideal der Wissenschaft und der Kunst in sich schliesst. Die Kunst und die Wissenschaft, die dem Kriege dient, ist nicht die höchste und echte, die ist es, die der Friede erzeugt und die den Frieden erzeugt. Und ich trinke auf den grossen letzten und rein idealen Nobelpreis, den die Menschheit dann sich wird zuerkennen dürfen, wenn die rohe Kraft unter den Völkern ebenso verhasst geworden ist, wie die rohe Kraft es bereits unter den menschlichen Individuen der zivilisierten Gesellschaft ist.

The Nobel Foundation's copyright has expired.Gerhart Hauptmann – Documentary

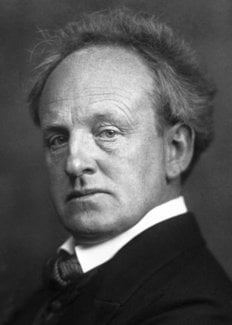

Gerhart Hauptmann – Photo gallery

Color silkscreen poster for the Federal Theatre Project presentation of The Weavers (Die Weber) by Gerhart Hauptmann at the Mayan Theatre, Los Angeles, California. From between 1936 and 1941.

Source: United States Library of Congress

Public domain via Wikimedia Commons

Gerhart Hauptmann – Nominations

Gerhart Hauptmann – Other resources

Links to other sites

On Gerhart Hauptmann on Pegasos Author’s Calendar

Award ceremony speech

Presentation Speech by Hans Hildebrand, Acting Secretary of the Swedish Academy, on December 10, 1912

There is an old saying that times change and men change with them. If we look back on past ages we discover its truth. We, who are no longer young, have had the opportunity in our bustling lives to experience the truth of the saying, and every day confirms it anew. As far back as history extends we find that new things emerged, but were not at first recognized although they were to be important in the future. A seed came alive and grew to magnificent size. Certain names in contemporary science illustrate the discrepancy between modest beginnings and later developments.

The same is true of dramatic poetry. This is not the place to trace its development through twenty-five centuries. There is a tremendous difference, however, between the satyr choruses of the Dionysiac festivals, called tragedies because of the goat skins worn by the chorus, and the demands the modern age makes on dramatic poetry, and this difference indicates considerable progress.

In our time Gerhart Hauptmann has been a great name in the field of drama. He turned fifty recently; he is thus in his prime of life and can look back on an exceptionally rich career as an artist. He submitted his first work to the stage at the age of twenty-seven. At the age of thirty he proved himself a mature artist with his play Die Weber (1892) [The Weavers]. This work was followed by others which confirmed his reputation. In most of his plays he deals with conditions of the low-class life which he had numerous occasions to study, especially in his native Silesia. His descriptions are based on keen observations of man and his milieu. Each of his characters is a fully developed personality – there is not a trace of types or clichés. Nobody even for a moment could doubt the truthfulness of his observations; they have established Hauptmann as a great realist. But he nowhere praises the life of these so-called low characters. On the contrary, when one has seen or read these plays and identified himself deeply with the conditions they represent, he feels the need for fresh air and asks how such misery can be abolished in the future. The realism in Hauptmann’s plays leads necessarily to brighter dreams of new and better conditions and to the wish for their fulfilment.

Hauptmann has also written dramas of a totally different nature: he calls them «Märchendramen». Among them is the delightful Hanneles Himmelfahrt (1893) [The Assumption of Hannele], in which the misery of life and the bliss of heaven emerge with such striking contrast. Among these plays is also Die versunkene Glocke (1897) [The Sunken Bell], the most popular of his plays in his own country. The copy used by the Nobel Committee of the Swedish Academy bore the stamp of the sixtieth impression.

Hauptmann has also distinguished himself in the genres of historical drama and comedy. He has not published a collection of his lyrical poems, but incidental poems in his plays bear witness to his talent in this field.

In his early years he had published a few short stories, but in 1910 he brought out his novel Der Narr in Christo Emanuel Quint [The Fool in Christ: Emanuel Quint], the result of many years of work. The story «Der Apostel» of 1892 is a sketch of the final work in which we learn about the inner life of a poor man who, without any education other than that acquired from the Bible and without any critical judgment of what he has read, finally reaches the conclusion that he is the reincarnation of Christ. It is not easy to give a correct account of the development of a human soul that can be considered normal, in view of all the forces and circumstances that affect its development. But it is even more difficult to attain the truth if one describes the inner development of a soul that is in certain respects abnormal. The attempt is bold; its execution took decades of creative work. Judgment of the work has differed widely. I am happy to join the many who consider Emanuel Quint a masterly solution of a difficult problem.

Hauptmann’s particular virtue is his penetrating and critical insight into the human soul. It is this gift that enabled him in his plays and in his novels to create truly living individuals rather than types representing some particular outlook or opinion. All the characters we meet, even the minor ones, have a full life. In his novels one admires the descriptions of the setting, as well as the sketches of the people that come in more or less close contact with the protagonist of the story. The plays reveal his great art by their powerful concentration which holds the reader or spectator from beginning to end. Whatever subject he treats, even when he deals with life’s seamy side, his is always a noble personality. That nobility and his refined art give his works their wonderful power.

The preceding remarks were intended to sketch the reasons why the Swedish Academy has awarded this year’s Nobel Prize to Gerhart Hauptmann.

Dr. Hauptmann – In your significant and controversial book Der Narr in Christo Emanuel Quint you say: «It is impossible to uncover the necessary course of a human life in all its stages, if only because every human being is something unique from beginning to end and because the observer can comprehend his object only within the limits of his own nature.»

That is indeed true. But there are many kinds of observers. The everyday man in the midst of his bustling life has neither the opportunity nor the will to study his fellow men in greater depth. We see the outside but do not care to see beneath it unless we happen to have a special interest in learning another’s motives. Even those who are not drawn into the turmoil of present life, who limit their intercourse with the outside world and are on intimate terms with their immediate surroundings, do not generally go very far in their study of the human soul. We are attracted or repelled; we love or hate, if we are not indifferent. We praise or blame.

The poet, however, is not an everyday man. He is able to extend the scope of his imagination much further. For he has the divine gift of intuition. And you, Dr. Hauptmann, possess this wonderful gift to the highest degree. In your many works you have created innumerable characters. But they do not exist merely as so many types of such and such a nature. To the reader and spectator of your plays, each of your characters is a fully developed individual, living and acting together with others, but different from all of them. That is the reason for much of the magic of your work.

It has been said that at least in some of your works you have been a marked realist. You have had rich opportunities to use your gift of observation and become acquainted with the misery of whole classes of people, and you have described it faithfully. If after seeing or reading such a play one is deeply moved by it, he cannot help thinking, «These conditions must be improved.» One cannot deny the existence of the seamy side of life, and it must have its place in literature in order to teach wisdom to the living.

Your manifold activities as a writer have given us other marvellous works. I shall mention only two here, Hanneles Himmefahrt and Die versunkene Glocke. The latter seems to enjoy great popularity in your country.

Through the mouth of the ambitious and unfortunate Michael Kramer you say:

If someone has the effrontery to paint the man with the crown of thorns – it will take him a lifetime to do it. No pleasures for him: lonely hours, lonely days, lonely years. He must be alone with himself and with his God. He must consecrate himself daily. Nothing common must be about him or in him. And then when he struggles and toils in his solitude the Holy Ghost comes. Then he can sometimes catch a glimpse. It swells, he can feel it. Then he rests in the eternal and he has it before him in quiet and beauty. He has it without wanting it. He sees the Saviour. He feels him.

Although in your work you have not represented the Saviour with the crown of thorns, you have represented a poor man ultimately driven to the delusion that he is the second Christ. But Kramer’s words reflect your own attitude. Your novel Der Narr in Christo Emanuel Quint appeared in 1910, but the story «Der Apostel» of 1892 shows that the plan for writing the novel had occurred to you twenty years earlier.

True art does not consist in writing down and handing to the public the thoughts of the moment, but rather in subjecting potentially useful ideas to close scrutiny, to the conflict of different opinions and the apprehensive consideration of their eventual effect. This process will gradually lead the true artist to the precious conviction, «I have finally reached the truth.» You have attained the highest rank of art by painstaking but never pedantic preparatory research, by the consistency of your feelings, thoughts, and actions, and by the strict form of your plays.

The Swedish Academy has found the great artist Gerhart Hauptmann worthy of receiving this year’s Nobel Prize, which his Majesty the King will now present to him.

The Nobel Prize in Literature 1912

Gerhart Hauptmann – Biographical

I was born on November 15, 1862. The place of my birth is Bad Obersalzbrunn, a spa famous for its medicinal springs. The house of my birth is the inn «Zur Preussischen Krone». My father was Robert Hauptmann, my mother Marie Hauptmann, née Straehler. I am the youngest of four children. I remember growing up in an educated and lively middle-class house.

I attended the village school, learned some Latin from a tutor, and had violin lessons. Later I went to Breslau, the capital of our province, where I lived in boardinghouses and attended a Gymnasium. Fortunately, my Breslau school period did not crush me, but it left scars from which I only slowly recovered.

I should have perished if there had not been a way out. I went to the country and began to study agriculture. The tortures of school, begun in 1874, ended in 1878. But agriculture remained an episode. Once in solitude I learned to stand on my own feet and have my own thoughts. I grew conscious of myself, my value, and my rights. In this way I gained independence, firmness, and a freedom of intellect that I still enjoy today.

Hungry for culture, I resumed to Breslau where I spent a second, happier period. I attended the art academy, did sculpturing, learned what youth, hope, and beauty are, the value of friends, masters, and teachers.

I drew, sculptured, drank, wrote poems, made plans, and built castles in Spain. In this mood I exchanged the art academy of Breslau for the University of Jena in Thuringia. In this mood I exchanged Jena for Rome, and later Rome for Berlin.

Although I still worked as a sculptor in Rome, it was here that I finally decided upon literature. A play Vor Sonnenaufgang [Before Dawn] made me publicly known in 1889.

My later works I wrote partly in Berlin, partly in Schreiberhau in the Riesengebirge, partly in Agnetendorf, partly in Italy: they are the condensation of outward and inward fortunes.

Biographical note on Gerhart Hauptmann

Gerhart Hauptmann (1862-1946) gained fame as one of the founders of German Naturalism. After Vor Sonnenaufgang, which created a scandal and, at the same time, was hailed as the beginning of naturalistic drama in Germany, he wrote his most successful play, Die Weber (1892) [The Weavers], the comedy Der Biberpelz (1893) [The Beaver Coat], the historical drama Florian Geyer (1896), Fuhrmann Henschel (1898) [Drayman Henschel], Rose Bernd (1903), and Die Ratten (1911) [The Rats]. But he also wrote symbolic works like Hanneles Himmelfahrt (1893) [The Assumption of Hannele] and Die versunkene Glocke (1896) [The Sunken Bell]. Hauptmann’s later works are often literary in inspiration to the point of being – in the widest sense – revisions of European classics. Der arme Heinrich (1902) [Henry of Auë] is modelled on a German medieval romance; Hamlet in Wittenberg (1935) challenged Shakespeare and Der grosse Traum (1942-43) [The Great Dream] Dante. Greece influenced him deeply, but in his image of Greece archaic and chthonic features predominated: Griechischer Frühling (1908) [Greek Spring], Der Bogen des Odysseus (1914) [The Bow of Odysseus], and above all the Atridentetralogie, of which the last two parts, Agamemnons Tod [Agamemnon’s Death] and Elektra, were published posthumously in 1948.

Other works include the erotic novel Der Ketzer von Soana (1918) [The Heretic of Soana], Buch der Leidenschaft (1930) [Book of Passion], a thinly veiled account of his divorce and remarriage in 1904, and the two autobiographical volumes Abenteuer meiner Jugend (1937 and 1949) [Adventure of My Youth]. His collected works in seventeen volumes were published in 1942.

This autobiography/biography was written at the time of the award and first published in the book series Les Prix Nobel. It was later edited and republished in Nobel Lectures. To cite this document, always state the source as shown above.

Gerhart Hauptmann died on June 6, 1946.

The Nobel Foundation's copyright has expired.