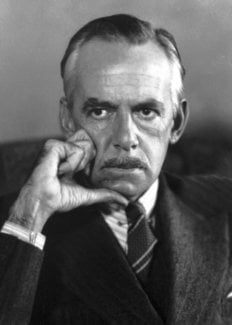

Eugene O’Neill – Nobel diploma

Eugene O’Neill – Banquet speech

As the Laureate was unable to be present at the Nobel Banquet at the City Hall in Stockholm, December 10, 1936, the speech was read by James E. Brown, Jr., American Chargé d’Affaires

It is an extraordinary privilege that has come to me to take before this gathering of eminent persons the place of my fellow-countryman, Mr. Eugene O’Neill, recipient of the Nobel Prize in Literature, who unfortunately is unable to be present here today.

It is an extraordinary privilege because the significance and true worth of the Nobel Prizes are fully recognized in all advanced parts of the world. The Prizes are justly held in honor and esteem, for it is well known that they are awarded without prejudice of any kind by the several committees whose members generously devote much time and thought to the task in their charge.

In addition to being a stimulus to endeavour and a high recognition of achievement, the Prizes are valuable in another respect. Owing to the complete absence of partiality in the awarding of them, they induce people of all countries to think in terms of the world and mankind, heedless of classifications or boundaries of any character. The good influence of such conspicuous recognition of a particular achievement thus spreads far beyond its special purpose.

Mr. O’Neill has been prevented from being here today principally because the state of his health, damaged by overwork, has forced him to follow his doctor’s orders to live absolutely quietly for several months. It is his hope, and I follow his own words in a letter to me, that all those connected with the festival will accept in good faith his statement of the impossibility of his attending, and not put it down to arbitrary temperament, or anything of the sort.

In view of his inability to attend, he promptly sent a speech to be read on his behalf on this occasion. Mr. O’Neill in a letter to me said regarding his speech, «It is no mere artful gesture to please a Swedish audience. It is a plain statement of fact and my exact feeling, and I am glad of this opportunity to get it said and on record.» It affords me great pleasure to read now the speech addressed to this gathering by Mr. Eugene O’Neill.

«First, I wish to express again to you my deep regret that circumstances have made it impossible for me to visit Sweden in time for the festival, and to be present at this banquet to tell you in person of my grateful appreciation.

It is difficult to put into anything like adequate words the profound gratitude I feel for the greatest honor that my work could ever hope to attain, the award of the Nobel Prize. This highest of distinctions is all the more grateful to me because I feel so deeply that it is not only my work which is being honored, but the work of all my colleagues in America – that this Nobel Prize is a symbol of the recognition by Europe of the coming-of-age of the American theatre. For my plays are merely, through luck of time and circumstance, the most widely-known examples of the work done by American playwrights in the years since the World War – work that has finally made modern American drama in its finest aspects an achievement of which Americans can be justly proud, worthy at last to claim kinship with the modern drama of Europe, from which our original inspiration so surely derives.

This thought of original inspiration brings me to what is, for me, the greatest happiness this occasion affords, and that is the opportunity it gives me to acknowledge, with gratitude and pride, to you and to the people of Sweden, the debt my work owes to that greatest genius of all modern dramatists, your August Strindberg.

It was reading his plays when I first started to write back in the winter of 1913-14 that, above all else, first gave me the vision of what modern drama could be, and first inspired me with the urge to write for the theatre myself. If there is anything of lasting worth in my work, it is due to that original impulse from him, which has continued as my inspiration down all the years since then – to the ambition I received then to follow in the footsteps of his genius as worthily as my talent might permit, and with the same integrity of purpose.

Of course, it will be no news to you in Sweden that my work owes much to the influence of Strindberg. That influence runs clearly through more than a few of my plays and is plain for everyone to see. Neither will it be news for anyone who has ever known me, for I have always stressed it myself. I have never been one of those who are so timidly uncertain of their own contribution that they feel they cannot afford to admit ever having been influenced, lest they be discovered as lacking all originality.

No, I am only too proud of my debt to Strindberg, only too happy to have this opportunity of proclaiming it to his people. For me, he remains, as Nietzsche remains in his sphere, the Master, still to this day more modern than any of us, still our leader. And it is my pride to imagine that perhaps his spirit, musing over this year’s Nobel award for literature, may smile with a little satisfaction, and find the follower not too unworthy of his Master.»

Prior to the speech, Robert Fries, Director of the Bergius Foundation, remarked: «It is difficult to explain the vital processes in the living organism; it is difficult to interpret the inmost essence of matter, but it is perhaps most difficult to sound the human mind and to understand the soul in its shifting phases. With passionate intensity and impulsive genius Eugene O’Neill has done this in his dramas, and one cannot but be captivated by the masterly way in which he deals with the great problems of life.»

The Nobel Foundation's copyright has expired.Eugene O’Neill – Bibliography

| Books in English (American editions only) |

| Thirst and Other One Act Plays. – Boston : Gorham Press, 1914. – Content: Thirst, The Web, Warnongs, Fog, Recklessness |

| Bound East for Cardiff // Provincetown Plays : First Series. – New York : Frank Shay, 1916 |

| Before Breakfast // Provincetown Plays : Third Series. – New York : Frank Shay, 1916 |

| Ile. – New York: Egmont H. Arens, 1918 |

| The Moon of the Caribbees and Six Other Plays of the Sea. – New York : Boni & Liveright, 1919 |

| Beyond the Horizon. – New York : Boni & Liveright, 1920 |

| The Emperor Jones, Diff’rent, The Straw. – New York : Boni & Liveright, 1921 |

| Gold. – New York : Boni & Liveright, 1921 |

| The Hairy Ape, Anna Christie, The First Man. – New York : Boni & Liveright, 1922 |

| The Dreamy Kid // Contemporary One-Act Plays of 1921. – Cincinnati : Stewart Kidd Company, 1922 |

| All God’s Chillun Got Wings and Welded. – New York : Boni & Liveright, 1924 |

| The Complete Works of Eugene O’Neill. – 2 vol. – New York : Boni & Liveright, 1924 |

| Desire Under the Elms. – New York : Boni & Liveright, 1925 |

| The Great God Brown, The Fountain, The Moon of the Caribbees and Other Plays. – New York : Boni & Liveright, 1926 |

| Marco Millions. – New York : Boni & Liveright, 1927 |

| The American Caravan. – New York : The Macaulay Company, 1927. – Act one of Lazarus Laughed |

| Lazarus Laughed. – New York : Boni & Liveright, 1927 |

| Strange Interlude. – New York : Boni & Liveright, 1928 |

| Dynamo. – New York : Horace Liveright, 1929 |

| A Bibliography of the Works of Eugene O’Neill Together with the Collected Poems of Eugene O’Neill / edited by Ralph Sanborn and Barrett H. Clark. – New York : Random House, 1931 |

| Mourning Becomes Electra. – New York : Horace Liveright, 1931 |

| Nine Plays by Eugene O’Neill. – New York : Horace Liveright, 1932 |

| Ah, Wilderness! – New York : Random House, 1933 |

| Days Without End. – New York : Random House, 1934 |

| The Plays of Eugene O’Neill. – 12 vol. – New York : Scribners, 1934-1935 |

| The Long Voyage Home : Seven Plays of the Sea. – New York : Modern Library, 1940 |

| The Plays of Eugene O’Neill. – 3 vol. – New York : Random House, 1941 |

| The Iceman Cometh. – New York : Random House, 1946 |

| Lost Plays of Eugene O’Neill. – New York : New Fathoms, 1950 |

| A Moon for the Misbegotten. – New York : Random House, 1952 |

| Long Day’s Journey into Night. – New Haven : Yale University Press, 1956 |

| The Last Will and Testament of Silverdene Emblem O’Neill. – New Haven : Yale University Press, 1956 |

| A Touch of the Poet. – New Haven : Yale University Press, 1957 |

| Hughie. – New Haven : Yale University Press, 1959 |

| Inscriptions : Eugene O’Neill to Carlotta Montgomery O’Neill. – New Haven : Yale University Press, 1960 |

| Ten “Lost” Plays. – New York : Random House, 1964 |

| More Stately Mansions. – New Haven : Yale University Press, 1964 |

| Six Short Plays. – New York: Vintage Books, 1965 |

| Children of the Sea and Three Other Unpublished Plays by Eugene O’Neill / edited by Jennifer McCabe Atkinson. – Washington, D.C. : NCR Microcard Editions, 1972 |

| Poems 1912-1942 / edited by Donald C. Gallup. – New Haven : Yale University Library, 1979 |

| The Calms of Capricorn / edited by Donald C. Gallup. – 2 vol. – New Haven: Yale University Library, 1981 |

| Eugene O’Neill At Work : Newly Released Ideas for Plays / edited by Virginia Floyd. – New York : Ungar, 1981 |

| Work Diary 1924-1943 / edited by Donald C. Gallup. – 2 vol. – New Haven: Yale University Library, 1981 |

| Chris Christophersen : A Play in Three Acts. – New York : Random House, 1982 |

| The Unknown O’Neill : Unpublished or Unfamiliar Writings of Eugene O’Neill / edited by Travis Bogard. – New Haven : Yale University Press, 1988 |

| The Unfinished Plays : Notes for The Visit of Malatesta, The Last Conquest, Blind Alley Guy / edited by Virginia Floyd. – New York : Continuum, 1988 |

| Complete Plays / edited by Travis Bogard. – 3 vol. – New York: Viking, 1988 |

| Critical studies (a selection) |

| Winther, Sophus Keith, Eugene O’Neill : a Critical Study. – New York : Random House, 1934 |

| Skinner, Richard Dana, Eugene O’Neill : a Poet’s Quest. – New York : Longmans, Green, 1935 |

| Boulton, Agnes, Part of a Long Story : Eugene O’Neill as a Young Man in Love. – London : Peter Davies, 1958 |

| Falk, Doris Virginia, Eugene O’Neill and the Tragic Tension : an Interpretative Study of the Plays. – New Brunswick, N.J. : Rutgers Univ. Press, 1958 |

| O’Neill and his Plays : Four Decades of Criticism / ed. by Oscar Cargill … – New York, 1961 |

| Gelb, Arthur, & Gelb, Barbara, O’Neill. – New York : Harper, 1962 |

| Sheaffer, Louis, O’Neill : Son and Playwright. – Boston : Little, Brown, 1968 |

| Sheaffer, Louis, O’Neill : Son and Artist. – Boston : Little, Brown, 1973 |

| Critical Essays on Eugene O’Neil / compiled by James J. Martine. – Boston, Mass. : G.K. Hall, 1984 |

| Critical approaches to O’Neill / edited by John H. Stroupe. – New York : AMS Press, 1988 |

| Alexander, Doris, Eugene O’Neill’s Creative Struggle : The Decisive Decade, 1924-1933. – University Park : Pennsylvania State University Press, 1992 |

| Black, Stephen A., Eugene O’Neill : Beyond Mourning and Tragedy. – New Haven : Yale University Press, 1999 |

The Swedish Academy, 2007

Eugene O’Neill – Nominations

Eugene O’Neill – Other resources

Links to other sites

On Eugene O’Neill from Pegasos Author’s Calendar

Eugene O’Neill National Historic Site

eOneill.com – An electronic Eugene O’Neill Archive

Selected Poetry of Eugene O’Neill from Representative Poetry Online, University of Toronto Libraries

‘American Masters: Eugene O’Neill’ from PBS

Eugene O’Neill – Biographical

Born October 16th, 1888, in New York City. Son of James O’Neill, the popular romantic actor. First seven years of my life spent mostly in hotels and railroad trains, my mother accompanying my father on his tours of the United States, although she never was an actress, disliked the theatre, and held aloof from its people.

From the age of seven to thirteen attended Catholic schools. Then four years at a non-sectarian preparatory school, followed by one year (1906-1907) at Princeton University.

After expulsion from Princeton I led a restless, wandering life for several years, working at various occupations. Was secretary of a small mail order house in New York for a while, then went on a gold prospecting expedition in the wilds of Spanish Honduras. Found no gold but contracted malarial fever. Returned to the United States and worked for a time as assistant manager of a theatrical company on tour. After this, a period in which I went to sea, and also worked in Buenos Aires for the Westinghouse Electrical Co., Swift Packing Co., and Singer Sewing Machine Co. Never held a job long. Was either fired quickly or left quickly. Finished my experience as a sailor as able-bodied seaman on the American Line of transatlantic liners. After this, was an actor in vaudeville for a short time, and reporter on a small town newspaper. At the end of 1912 my health broke down and I spent six months in a tuberculosis sanatorium.

Began to write plays in the Fall of 1913. Wrote the one-act Bound East for Cardiff in the Spring of 1914. This is the only one of the plays written in this period which has any merit.

In the Fall of 1914, I entered Harvard University to attend the course in dramatic technique given by Professor George Baker. I left after one year and did not complete the course.

The Fall of 1916 marked the first production of a play of mine in New York – Bound East for Cardiff – which was on the opening bill of the Provincetown Players. In the next few years this theatre put on nearly all of my short plays, but it was not until 1920 that a long play Beyond the Horizon was produced in New York. It was given on Broadway by a commercial management – but, at first, only as a special matinee attraction with four afternoon performances a week. However, some of the critics praised the play and it was soon given a theatre for a regular run, and later on in the year was awarded the Pulitzer Prize. I received this prize again in 1922 for Anna Christie and for the third time in 1928 for Strange Interlude.

The following is a list of all my published and produced plays which are worth mentioning, with the year in which they were written:

Bound East for Cardiff (1914), Before Breakfast (1916), The Long Voyage Home (1917), In the Zone (1917), The Moon of the Carabbees (1917), Ile (1917), The Rope (1918), Beyond the Horizon (1918), The Dreamy Kid (1918), Where the Cross is Made (1918), The Straw (1919), Gold (1920), Anna Christie (1920), The Emperor Jones (1920), Different (1920), The First Man (1921), The Fountain (1921-22), The Hairy Ape (1921), Welded (1922), All God’s Chillun Got Wings (1923), Desire Under the Elms (1924), Marco Millions (1923-25), The Great God Brown (1925), Lazarus Laughed (1926), Strange Interlude (1926-27), Dynamo (1928), Mourning Becomes Electra (1929-31) , Ah, Wilderness (1932), Days Without End (1932-33).

Biographical note on Eugene O’Neill

After an active career of writing and supervising the New York productions of his own works, O’Neill (1888-1953) published only two new plays between 1934 and the time of his death. In The Iceman Cometh (1946), he exposed a «prophet’s» battle against the last pipedreams of a group of derelicts as another pipedream and managed to infuse into the «Lower Depths» atmosphere a sense of the tragic. A Moon for the Misbegotten (1952) contains a strong autobiographical content, which it shares with Long Day’s Journey into Night (posth. 1956), one of O’Neill’s most important works. The latter play, written, according to O’Neill, «in tears and blood… with deep pity and understanding and forgiveness for all the four haunted Tyrones», had its premiere at the Royal Dramatic Theatre in Stockholm. Sweden grew into an O’Neill centre with the first productions of the one-act play Hughie (posth. 1959) as well as A Touch of the Poet (posth. 1958) and an adapted version of More Stately Mansions (posth. 1962 ) – both plays being parts of an unfinished cycle in which O’Neill returned to his earlier attempts at making psychological analysis dramatically effective.

This autobiography/biography was written at the time of the award and first published in the book series Les Prix Nobel. It was later edited and republished in Nobel Lectures. To cite this document, always state the source as shown above.

Eugene O’Neill died on 27 November 1953.

The Nobel Foundation's copyright has expired.Award ceremony speech

Presentation Speech by Per Hallström, Permanent Secretary of the Swedish Academy, on December 10, 1936

Eugene O’Neill’s dramatic production has been of a sombre character from the very first, and for him life as a whole quite early came to signify tragedy.

This has been attributed to the bitter experiences of his youth, more especially to what he underwent as a sailor. The legendary nimbus that gathers around celebrities in his case took the form of heroic events created out of his background. With his contempt for publicity, O’Neill straightway put a stop to all such attempts; there was no glamour to be derived from his drab hardships and toils. We may indeed conclude that the stern experiences were not uncongenial to his spirit, tending as they did to afford release of certain chaotic forces within him.

His pessimism was presumably on the one hand an innate trait of his being, on the other an offshoot of the literary current of the age, though possibly it is rather to be interpreted as the reaction of a profound personality to the American optimism of old tradition. Whatever the source of his pessimism may have been, however, the line of his development was marked out, and O’Neill became by degrees the uniquely and fiercely tragic dramatist that the world has come to know. The conception of life that he presents is not a product of elaborate thinking, but it has the genuine stamp of something lived through. It is based upon an exceedingly intense, one might say, heart-rent, realization of the austerity of life, side by side with a kind of rapture at the beauty of human destinies shaped in the struggle against odds.

A primitive sense of tragedy, as we see, lacking moral backing and achieving no inner victory – merely the bricks and mortar for the temple of tragedy in the grand and ancient style. By his very primitiveness, however, this modern tragedian has reached the well-spring of this form of creative art, a naive and simple belief in fate. At certain stages it has contributed a stream of pulsating life-blood to his work.

That was, however, at a later period. In his earliest dramas O’Neill was a strict and somewhat arid realist; those works we may here pass by. Of more moment were a series of one-act plays, based upon material assembled during his years at sea. They brought to the theatre something novel, and hence he attracted attention.

Those plays were not, however, dramatically notable; properly speaking, merely short stories couched in dialogue-form; true works of art, however, of their type, and heart-stirring in their simple, rugged delineation. In one of them, The Moon of the Caribbees (1918), he attains poetic heights, partly by the tenderness in depicting the indigence of a sailor’s life with its naive illusions of joy, and pertly by the artistic background of the play: dirge-like Negro songs coming from a white coral shore beneath metallically glittering palms and the great moon of the Caribbean Sea. Altogether it is a mystical weave of melancholy, primitive savagery, yearning, lunar effulgence, and oppressive desolateness.

The drama Anna Christie (1921) achieves its most striking effect through the description of sailors’ life ashore in and about waterfront saloons. The first act is O’Neill’s masterpiece in the domain of strict realism, each character being depicted with supreme sureness and mastery. The content is the raising of a fallen Swedish girl to respectable human status by the strong and wholesome influences of the sea; for once pessimism is left out of the picture, the play having what is termed a happy ending.

With his drama The Hairy Ape (1922), also concerned with sailors’ lives, O’Neill launches into that expressionism which sets its stamp upon his «ideadramas». The aim of expressionism in literature and the plastic arts is difficult to determine; nor need we discuss it, since for practical purposes a brief description suffices. It endeavours to produce its effects by a sort of mathematical method; it may be said to extract the square root of the complex phenomena of reality, and build with those abstractions a new world on an enormously magnified scale. The procedure is an irksome one and can hardly be said to achieve mathematical exactitude; for a long time, however, it met with great success throughout the world.

The Hairy Ape seeks to present on a monumental scale the rebellious slave of steam power, intoxicated with his force and with superman ideas. Outwardly he is a relapse to primitive man, and he presents himself as a kind of beast, suffering from yearning for genius. The play depicts his tragical discomfiture and ruin on being brought up against cruel society.

Subsequently O’Neill devoted himself for a number of years to a boldly expressionistic treatment of ideas and social questions. The resulting plays have little connection with real life; the poet and dreamer isolates himself, becoming absorbed in feverishly pursued speculation and phantasy.

The Emperor Jones (1920), as an artistic creation, stands rather by itself; through it the playwright first secured any considerable celebrity. The theme embraces the mental breakdown of a Negro despot who rules over a Negro-populated island in the West Indies. The despot perishes on the flight from his glory, hunted in the dead of night by the troll-drums of his pursuers and by recollections of the past shaping themselves as paralyzing visions. These memories stretch back beyond his own life to the dark continent of Africa. Here lies concealed the theory of the individual’s unconscious inner life being the carrier of the successive stages in the evolution of the race. As to the rightness of the theory we need form no opinion; the play takes so strong a hold upon our nerves and senses that our attention is entirely absorbed.

The «dramas of ideas» proper are too numerous and too diversified to be included in a brief survey. Their themes derive from contemporary life or from sagas and legends; all are metamorphosed by the author’s fancy. They play on emotional chords all tightly strung, give amazing decorative effects, and manifest a never-failing dramatic energy. Practically speaking, everything in human life in the nature of struggle or combat has here been used as a subject for creative treatment, solutions being sought for and tried out of the spiritual or mental riddles presented. One favourite theme is the cleavage of personality that arises when an individual’s true character is driven in upon itself by pressure from the world without, having to yield place to a make-believe character, its own live traits being hidden behind a mask. The dramatist’s musings are apt to delve so deep that what he evolves has an urge, like deep-sea fauna, to burst asunder on being brought into the light of day. The results he achieves, however, are never without poetry; there is an abundant flow of passionate, pregnant words. The action, too, yields evidence in every case of the never-slumbering energy that is one of O’Neill’s greatest gifts.

Underneath O’Neill’s fantastic love of experimenting, however, is a hint of a yearning to attain the monumental simplicity characteristic of ancient drama. In his Desire Under the Elms (1924) he made an attempt in that irection, drawing his motif from the New England farming community, hardened in te progress of generations into a type of Puritanism that had gradually come to forfeit its idealistic inspiration. The course embarked upon was to be followed with more success in the «Electra» trilogy.

In between appeared A Play; Strange Interlude (1928), which won high praise and became renowned. It is rightly termed «A Play», for with its broad and loose-knit method of presentation it cannot be regarded as a tragedy; it would rather seem most aptly defined as a psychological novel in scenes. To its subtitle, «Strange Interlude», a direct clue is given in the course of the play: «Life, the present, is the strange interlude between the past and what is to come.» The author tries to make his idea clear, as far as possible, by resorting to a peculiar device: on the one hand, the characters speak and reply as the action of the play demands; on the other, they reveal their real natures and their recollections in the form of monologues, inaudible to the other characters upon the stage. Once again, the element of masking!

Regarded as a psychological novel, up to the point at which it becomes too improbable for any psychology, the work is very notable for its wealth of analytical and above all intuitive acumen, and for the profound insight it displays into the inner workings of the human spirit. The training bore fruit in the real tragedy that followed, the author’s grandest work: Mourning Becomes Electra (1931). Both in the story it unfolds and in the destiny-charged atmosphere enshrouding it, this play keeps close to the tradition of the ancient drama, though in both respects it is adjusted to modern life and to modern lines of thought. The scene of this tragedy of the modern-time house of Atreus is laid in the period of the great Civil War, America’s Iliad. That choice lends the drama the clear perspective of the past and yet provides it with a background of intellectual life and thought sufficiently close to the present day. The most remarkable feature in the drama is the way in which the element of fate has been further developed. It is based upon up-to-date hypotheses, primarily upon the natural-scientific determinism of the doctrine of heredity, and also upon the Freudian omniscience concerning the unconscious, the nightmare dream of perverse family emotions.

These hypotheses are not, as we know, established beyond dispute, but the all-important point regarding this drama is that its author has embraced and applied them with unflinching consistency, constructing upon their foundation a chain of events as inescapable as if they had been proclaimed by the Sphinx of Thebes herself; Thereby he has achieved a masterly example of constructive ability and elaborate motivation of plot, and one that is surely without a counterpart in the whole range of latter-day drama. This applies especially to the first two parts of the trilogy.

Two dramas, wholly different and of a new type for O’Neill, followed. They constitute a characteristic illustration of the way he has of never resting content with a result achieved, no matter what success it may have met with. They also gave evidence of his courage, for in them he launched a challenge to a considerable section of those whose favourable opinions he had won, and even to the dictators of those opinions. Though it may not at the present time be dangerous to defy natural human feelings and conceptions, it is not by any means free from risk to prick the sensitive conscience of critics. In Ah, Wilderness (1933) the esteemed writer of tragedies astonished his admirers by presenting them with an idyllic middle-class comedy and carried his audiences with him. In its depiction of the spiritual life of young people the play contains a good deal of poetry, while its gayer scenes display unaffected humour and comedy; it is, moreover, throughout simple and human in its appeal.

In Days Without End (1934) the dramatist tackled the problem of religion, one that he had until then touched upon only superficially, without identifying himself with it, and merely from the natural scientist’s combative standpoint. In this play he showed that he had an eye for the irrational, felt the need of absolute values, and was alive to the danger of spiritual impoverishment in the empty space that will be all that is left over the hard and solid world of rationalism. The form the work took was that of a modern miracle play, and perhaps, as with his tragedies of fate, the temptation to experiment was of great importance in its origination. Strictly observing the conventions of the drama form chosen, he adopted medieval naiveté in his presentation of the struggle of good against evil, introducing, however, novel and bold features of stage technique. The principal character he cleaves into two parts, white and black, not only inwardly but also corporeally, each half leading its own independent bodily life – a species of Siamese twins contradicting each other. The result is a variation upon earlier experiments. Notwithstanding the risk attendant upon that venture, the drama is sustained by the author’s rare mastery of scenic treatment, while in the spokesman of religion, a Catholic priest, O’Neill has created one of his most lifelike characters. Whether that circumstance may be interpreted as indicating a decisive change in his outlook upon life remains to be seen in the future.

O’Neill’s dramatic production has been extraordinarily comprehensive in scope, versatile in character, and abundantly fruitful in new departures; and still its originator is at a stage of vigorous development. Yet in essential matters, he himself has always been the same in the exuberant end unrestrainably lively play of his imagination, in his never-wearying delight in giving shape to the ideas, whether emanating from within or without, that have jostled one another in the depths of his contemplative nature, and, perhaps first and foremost, in his possession of a proudly and ruggedly independent character.

In choosing Eugene O’Neill as the recipient of the 1936 Nobel Prize in Literature, the Swedish Academy can express its appreciation of his peculiar and rare literary gifts and also express their homage to his personality in these words: the Prize has been awarded to him for dramatic works of vital energy, sincerity, and intensity of feeling, stamped with an original conception of tragedy.