Samuel Beckett – Nominations

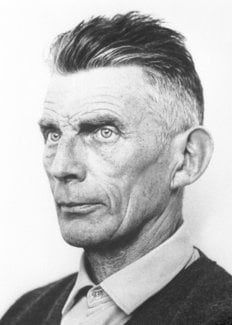

Samuel Beckett – Photo gallery

1 (of 1) Telegram to Samuel Beckett from the permanent secretary of the Swedish Academy telling him of the announcement of his Nobel Prize in Literatre.

© Swedish Academy archives

Samuel Beckett – Nobel Lecture

No lecture was delivered by Samuel Beckett.

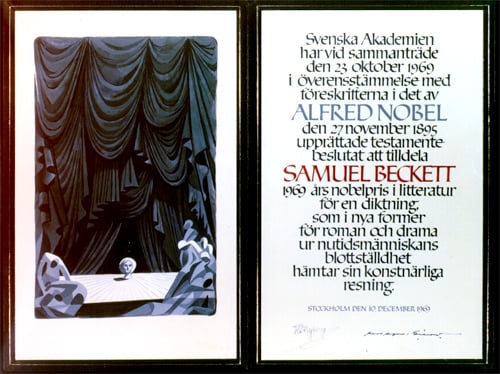

Samuel Beckett – Nobel diploma

Copyright © The Nobel Foundation 1969

Artist: Gunnar Brusewitz

Calligrapher: Kerstin Anckers

Samuel Beckett – Bibliography

| Works in English |

| Whoroscope : Poem on Time. – Paris : Hours, 1930 |

| Proust. – London : Chatto & Windus, 1931 ; New York : Grove, 1957 |

| More Pricks Than Kicks. – London : Chatto & Windus, 1934 ; New York : Grove, 1970 |

| Echo’s Bones and Other Precipitates. – Paris : Europa, 1935 |

| Murphy. – London : Routledge, 1938 ; New York : Grove, 1957 |

| Watt. – Paris : Olympia, 1953 ; New York : Grove, 1959 ; London : Calder, 1963 |

| All That Fall. – New York : Grove, 1957 ; London : Faber & Faber, 1957 |

| From an Abandoned Work. – London : Faber, 1958 |

| Krapp’s Last Tape and Other Dramatic Pieces. – New York : Grove, 1960. – Comprises Krapp’s Last Tape, All That Fall, Embers, Act Without Words I, and Act Without Words II |

| Happy Days. – New York : Grove, 1961; London : Faber, 1962 |

| Poems in English. – London : Calder, 1961 ; New York : Grove, 1963 |

| Play and Two Short Pieces for Radio. – London : Faber, 1964 |

| Eh Joe and Other Writings. – London : Faber, 1967. – Comprises Eh Joe, Act Without Words II, and Film |

| Breath and Other Shorts. – London : Faber, 1972. – Comprises Breath, Come and Go, Act Without Words I, Act Without Words II, and From an Abandoned Work |

| Not I. – London : Faber, 1973 |

| That Time. – London : Faber, 1976 |

| Fizzles. – New York : Grove, 1976 |

| All Strange Away. – New York : Gotham Book Mart, 1976 ; London : Calder, 1979 |

| Footfalls. – London : Faber, 1976 |

| Ends and Odds : Eight New Dramatic Pieces. – New York : Grove, 1976. – Comprises Not I, That Time, Footfalls, Ghost Trio, Theatre I, Theatre II, Radio I, and Radio II |

| Ends and Odds : Plays and Sketches. – London : Faber, 1977. – Comprises Not I, That Time, Footfalls, Ghost Trio, Theatre I, Theatre II, Radio I,Radio II, and … but the clouds … |

| Four Novellas. – London : Calder, 1977. – comprises First Love, The Expelled, The Calmative, and The End |

| Expelled, and Other Novellas. – New York : Penguin, 1980. – comprises First Love, The Expelled, The Calmative, and The End |

| Company. – New York : Grove, 1980 |

| Nohow On : Three Novels. – New York : Grove, 1980. – comprises Company, Ill Seen, Ill Said, and Worstward Ho |

| Rockaby and Other Short Pieces. – New York : Grove, 1981. – Comprises Rockaby, Ohio Impromptu, All Strange Away, and A Piece of Monologue |

| Three Plays. – New York : Grove, 1984. – Comprises Ohio Impromptu, Catastrophe, and What Where |

| As the Story Was Told. – Cambridge : Rampant Lions, 1987 |

| Stirrings Still. – New York : Blue Moon, 1988 ; London : Calder, 1988 |

| Dream of Fair to Middling Women / edited by Eoin O’Brien and Edith Fournier. – Dublin : Black Cat Press, 1992 |

| Works in French |

| Molloy. – Paris : Minuit, 1951 |

| Malone meurt. – Paris : Minuit, 1951 |

| En attendant Godot. – Paris : Minuit, 1952 |

| L’innommable. – Paris : Minuit, 1953 |

| Nouvelles et Textes pour rien. – Paris : Minuit, 1955 |

| Fin de partie, suivi de Acte sans paroles. – Paris : Minuit, 1957 |

| Têtes-Mortes. – Paris : Minuit, 1967. – Éd. Augm. 1972 |

| Acte sans paroles II // Dramatische Dichtungen. – Vol. 1. – Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp, 1963 |

| Comment c’est. – Paris : Minuit, 1961 |

| Imagination morte imaginez. – Paris : Minuit, 1965 |

| Assez. – Paris : Minuit, 1966 |

| Bing. – Paris : Minuit, 1966 |

| Poèmes. – Paris : Minuit, 1968 |

| Sans. – Paris : Minuit, 1969 |

| Le Dépeupleur. – Paris : Minuit, 1970 |

| Mercier et Camier. – Paris : Minuit, 1970 |

| Premier amour. – Paris : Minuit, 1970 |

| Pour finir encore et autres foirades. – Paris : Minuit, 1976 |

| Poèmes , suivi de Mirlitonnades. – Paris : Minuit, 1978 |

| Catastrophe et autres dramaticules. – Paris : Minuit, 1982 |

| Eleuthéria. – Paris : Minuit, 1995 |

| Translations into English |

| Molloy / translated by the author and Patrick Bowles. – Paris : Olympia, 1955 ; New York : Grove, 1955 |

| Malone Dies / translated by the author. – New York : Grove, 1956 ; London : Calder, 1958 |

| Waiting for Godot / translated by the author. – New York : Grove, 1954 ; London : Faber, 1956. – Rev. ed. / edited by Douglas McMillan and James Knowleson. – London : Faber, 1993 |

| The Unnamable. – New York : Grove, 1958 ; London : Calder & Boyars, 1975 |

| Stories and Texts for Nothing / translated by the author. – New York : Grove, 1967 |

| Endgame, followed by Act Without Words / translated by the author. – New York : Grove, 1958 ; London : Faber, 1958 |

| How It Is / translated by the author. – New York : Grove, 1964 ; London : Calder, 1964 |

| Imagination Dead Imagine / translated by the author. – London : Calder & Boyars, 1965 |

| No’s Knife : Collected Shorter Prose, 1945-1966 / translated from the French by the author and Richard Seaver. – London : Calder & Boyars, 1967 |

| Lessness / translated by the author. – London : Calder & Boyars, 1970 |

| The Lost Ones / translated by the author. – London : Calder & Boyars, 1972 ; New York : Grove, 1972 |

| Mercier and Camier / translated by the author. – London : Calder & Boyars, 1974 ; New York : Grove, 1975 |

| First Love / translated by the author. – London : Calder & Boyars, 1973 |

| For to End Yet Again and Other Fizzles / translated by the author. – London : Calder, 1976 |

| Eleutheria : A Play in Three Acts / translated by Michael Brodsky. – New York : Foxrock, 1995 |

| Eleuthéria. – translated by Barbara Wright. – London : Faber, 1996 |

| Translations into French |

| Murphy / translated into French by the author. – Paris : Bordas, 1947 |

| Watt / translated into French by the author, Ludovic Janvier, and Agnès Janvier. – Paris : Minuit, 1968 |

| Tous ceux qui tombent / translated into French by the author and Robert Pinget. – Paris : Minuit, 1957 |

| La Dernière Bande, suivi de Cendres / translated into French by the author and Pierre Leiris. – Paris : Minuit, 1960 |

| Oh les beaux jours / translated into French by the author. – Paris : Minuit, 1963 |

| Comédie et actes divers / translated into French by the author. – Paris : Minuit, 1966 |

| Film / translated into French by the author. – Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp, 1968 |

| Film, suivi de Souffle / translated into French by the author. – Paris : Minuit, 1972 |

| Oh les beaux jours, suivi de Pas moi / translated into French by the author. – Paris : Minuit, 1975 |

| Cette fois / translated into French by the author. – Paris : Minuit, 1978 |

| Foirade = Fizzles. – Bilingual ed. / translated into French by the author. – London & New York : Petersburg, 1976 ; Paris : Fequet & Baudier, 1976 |

| Pas / translated into French by the author. – Paris : Minuit, 1977 |

| Compagnie / translated into French by the author. – Paris : Minuit, 1979 |

| Mal vu mal dit / translated into French by the author. – Paris : Minuit, 1981 |

| Berceuse, suivi de Impromptu d’Ohio / translated into French by the author. – Paris : Minuit, 1982 |

| Solo, suivi de Catastrophe / translated into French by the author. – Paris : Minuit, 1982 |

| Collections |

| The Collected Works of Samuel Beckett. – 16 vol. – New York : Grove, 1970 |

| Collected Poems in English and French. – New York : Grove, 1977 ; London : Calder, 1977 |

| Disjecta : Miscellaneous Writings and a Dramatic Fragment / edited by Ruby Cohn. – London : Calder, 1983 ; New York : Grove, 1983 |

| Collected Shorter Plays. – New York : Grove, 1984 ; London : Faber, 1984 |

| Collected Poems 1930-1978. – London : Calder, 1984 |

| Collected Shorter Prose, 1945-1980. – London : Calder, 1984 |

| The Complete Dramatic Works. – London : Faber, 1986 |

| Samuel Beckett : The Complete Short Prose, 1929-1989 / edited, with an introduction, by S. E. Gontarski. – New York : Grove, 1995 |

| Poems : 1930-1989. – London : Calder, 2002 |

| Samuel Beckett : The Grove Centenary Edition of Samuel Beckett. – 4 vol. / ed. by Paul Auster. – New York : Grove Press, 2006 |

| Critical studies (a selection) |

| Esslin, Martin, The Theatre of the Absurd. – New York : Doubleday, 1961 |

| Kenner, Hugh, Samuel Beckett : a Critical Study. – London : Calder, 1962 |

| Fletcher, John, The Novels of Samuel Beckett. – London : Chatto & Windus, 1964 |

| Tindall, William York, Samuel Beckett. – New York, 1964 |

| Federman, Raymond, Journey to Chaos : Samuel Beckett’s Early Fiction. – Berkeley : Univ. of California Press, 1965 |

| Samuel Beckett : a Collection of Critical Essays. – Englewood Cliffs, N.J. : Prentice-Hall, 1965 |

| Beckett at 60 : a Festschrift. – London : Calder & Boyars, 1967 |

| Janvier, Ludovic, Pour Samuel Beckett. – Paris : Editions de Minuit, 1969 |

| Samuel Beckett Now : Critical Approaches to His Novels, Poetry, and Plays. – Chicago, Ill., 1970 |

| Hagberg, Per Olof, The Dramatic Works of Samuel Beckett and Harold Pinter : a Comparative Analysis of Main Themes and Dramatic Technique. – Göteborg, 1972 |

| Webb, Eugene, The Plays of Samuel Beckett. – London : Owen, cop. 1972 |

| Samuel Beckett : the Critical Heritage. – London : Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1979 |

| Fletcher, John, Beckett : the Playwright. – New York : Hill and Wang, 1985 |

| O’Brien, Eoin, The Beckett Country : Samuel Beckett’s Ireland. – London : Faber, 1986 |

| Begam, Richard, Samuel Beckett and the End of Modernity. – Stanford, Calif. : Stanford University Press, 1996 |

| Cronin, Anthony, Samuel Beckett :the Last Modernist. – London : HarperCollins, 1996 |

| Knowlson, James, Damned to Fame : the Life of Samuel Beckett. – London : Bloomsbury, 1996 |

| Davies, Paul, Beckett and Eros : Death of Humanism. – Basingstoke : Macmillan, 2000 |

| Atik, Anne, How it Was :a Memoir of Samuel Beckett. – London : Faber, 2001 |

| Gordon, Lois G., Reading Godot. – New Haven, Conn. : Yale Univ. Press, 2002 |

| Albright, Daniel, Beckett and aesthetics. – Cambridge : Cambridge University Press, 2003 |

| Beckett Remembering, Remembering Beckett : Uncollected Interviews with Samuel Beckett and Memories of Those Who Knew Him. – London : Bloomsbury, 2006 |

| Pilling, John., A Samuel Beckett Chronology. – Basingstoke : Palgrave Macmillan, 2006 |

The Swedish Academy, 2006

Samuel Beckett – Other resources

Links to other sites

The Samuel Beckett Endpage at University of Antwerp

On Samuel Beckett from Pegasos Author’s Calendar

The Samuel Beckett Research Centre at University of Reading

Samuel Beckett – Facts

Award ceremony speech

Presentation Speech by Karl Ragnar Gierow, of the Swedish Academy

(Translation)

Your Majesty, Your Royal Highnesses, Ladies and Gentlemen,

Mix a powerful imagination with a logic in absurdum, and the result will be either a paradox or an Irishman. If it is an Irishman, you will get the paradox into the bargain. Even the Nobel Prize in Literature is sometimes divided. Paradoxically, this has happened in 1969, a single award being addressed to one man, two languages and a third nation, itself divided.

Samuel Beckett was born near Dublin in 1906. As a renowned author he entered the world almost half a century later in Paris when, in the space of three years, five works were published that immediately brought him into the centre of interest: the novel Molloy in 1951; its sequel, Malone Meurt, in the same year; the play, En Attendant Godot in 1952; and in the following year the two novels, L’lnnommable, which concluded the cycle about Molloy and Malone, and Watt.

These dates simply record a sudden appearance. The five works were not new at the time of publication, nor were they written in the order in which they appeared. They had their background in the current situation as well as in Beckett’s previous development. The true nature of Murphy , a novel from 1938, and the studies of Joyce (1929) and Proust (1931), which illuminate his own initial position, is perhaps most clearly seen in the light of Beckett’s subsequent production. For while he has pioneered new modes of expression in fiction and on the stage, Beckett is also allied to tradition, being closely linked not only to Joyce and Proust but to Kafka as well, and the dramatic works from his debut have a heritage from French works of the 1890s and Alfred Jarry’s Ubu Roi.

In several respects, the novel Watt marks a change of phase in this remarkable output. Written in 1942-44 in the South of France – whence Beckett fled from the Nazis, having lived for a long time in Paris – it was to be his last work in English for many years; he made his name in French and did not return to his native tongue for about fifteen years. The world around had also changed when Beckett came to write again after Watt. All the other works which made his name were written in the period 1945-49. The Second World War is their foundation; it was after this that his authorship achieved maturity and a message. But these works are not about the war itself, about life at the front, or in the French resistance movement (in which Beckett took an active part), but about what happened afterwards, when peace came and the curtain was rent from the unholiest of unholies to reveal the terrifying spectacle of the lengths to which man can go in inhuman degradation – whether ordered or driven by himself – and how much of such degradation man can survive. In this sense the degradation of humanity is a recurrent theme in Beckett’s writing and to this extent, his philosophy, simply accentuated by elements of the grotesque and of tragic farce, can be described as a negativism that cannot desist from descending to the depths. To the depths it must go because it is only there that pessimistic thought and poetry can work their miracles. What does one get when a negative is printed? A positive, a clarification, with black proving to be the light of day, the parts in deepest shade those which reflect the light source. Its name is fellow-feeling, charity. There are precedents besides the accumulation of abominations in Greek tragedy which led Aristotle to the doctrine of catharsis, purification through horror. Mankind has drawn more strength from Schopenhauer’s bitter well than from Schelling’s beatific springs, has been more blessed by Pascal’s agonized doubt than by Leibniz’s blind rational trust in the best of all possible worlds has reaped – in the field of Irish literature, which has also fed Beckett’s writing – a much leaner harvest from the whitewashed clerical pastoral of Oliver Goldsmith than from Dean Swift’s vehement denigration of all humankind.

Part of the essence of Beckett’s outlook is to be found here – in the difference between an easily-acquired pessimism that rests content with untroubled scepticism, and a pessimism that is dearly bought and which penetrates to mankind’s utter destitution. The former commences and concludes with the concept that nothing is really of any value, the latter is based on exactly the opposite outlook. For what is worthless cannot be degraded. The perception of human degradation – which we have witnessed, perhaps, to a greater extent than any previous generation – is not possible if human values are denied. But the experience becomes all the more painful as the recognition of human dignity deepens. This is the source of inner cleansing, the life force nevertheless, in Beckett’s pessimism. It houses a love of mankind that grows in understanding as it plumbs further into the depths of abhorrence, a despair that has to reach the utmost bounds of suffering to discover that compassion has no bounds. From that position, in the realms of annihilation, rises the writing of Samuel Beckett like a miserere from all mankind, its muffled minor key sounding liberation to the oppressed, and comfort to those in need.

This seems to be stated most clearly in the two masterpieces, Waiting for Godot and Happy Days, each of which, in a way, is a development of a biblical text. In the case of Godot we have, ‘Art thou he that should come, or do we look for another?’ The two tramps are confronted with the meaninglessness of existence at its most brutal. It may be a human figure; no laws are as cruel as those of creation and man’s peculiar status in creation comes from being the only creature to apply these laws with deliberately evil intent. But if we conceive of a providence – a source even of the immeasurable suffering inflicted by, and on, mankind – what sort of almighty is it that we – like the tramps – are to meet somewhere, some day? Beckett’s answer consists of the title of the play. By the end of the performance, as at the end of our own, we know nothing about this Godot. At the final curtain we have no intimation of the force whose progress we have witnessed. But we do know one thing, of which all the horror of this experience cannot deprive us: namely, our waiting. This is man’s metaphysical predicament of perpetual, uncertain expectation, captured with true poetic simplicity: En attendant Godot, Waiting for Godot.

The text for Happy Days – “a voice crying in the wilderness” – is more concerned with the predicament of man on earth, of our relationships with one another. In his exposition Beckett has much to say about our capacity for entertaining untroubled illusions in a wilderness void of hope. But this is not the theme. The action simply concerns how isolation, how the sand rises higher and higher until the individual is completely buried in loneliness. Out of the suffocating silence, however, there still rises the head, the voice crying in the wilderness, man’s indomitable need to seek out his fellow men right to the end, speak to his peers and find in companionship his solace.

L’Académie Suédoise regrette que Samuel Beckett ne soit pas parmi nous aujourd’hui. Cependant il a choisi pour le représenter l’homme qui le premier a découvert l’importance de l’oeuvre maintenant récompensée, son editeur a Paris, M. Jérôme Lindon, et je vous prie, cher Monsieur, de vouloir bien recevoir de la main de Sa Majesté le Roi le Prix Nobel de littérature, décerné par l’Académie à Samuel Beckett.

The Nobel Prize in Literature 1969

Samuel Beckett – Biographical

Bio-bibliographic information

1906 – Born in Dublin of Irish parents

1927 – B.A. Trinity College, Dublin

1928-29 – English reader at École Normale Supérieure, Paris

1930 – French reader at Trinity College, Dublin

1938 – Moved to France

1945 – Began writing in French

1989 – Died in Paris

Samuel Beckett died on 22 December 1989.