Jaroslav Seifert – Nobel Lecture

English

Czech

Pøedná¹ka k udìlení Nobelovy ceny.

V prosinci 1984.

O patetickém a lyrickém stavu ducha

Často se setkávám, především u cizinců, s otázkou, čím je možno vysvětlit velkou oblibu poezie v mé zemi, proč je u nás nejen zájem o básně, ale dokonce potřeba poezie, a tím snad i schopnost ji vnímat, znatelně větší než jinde.

Je to dáno podle mého mínění dějinami českého národa v posledních čtyřech stech letech a především naším národním obrozením na počátku devatenáctého století. Ztráta politické samostatnosti ve třicetileté válce připravila nás o duchovní a politickou elitu, neboťta byla umlčena nebo nucena opustit zemi, pokud neskončila na popravištích. Došlo nejen k přerušení kulturního vývoje, ale i k úpadku jazyka, nejen k násilné rekatolizaci, ale i k násilné germanizaci.

Na počátku devatenáctého století přinesl však vliv francouzské revoluce i romantismu nové podněty a nový zájem nejen o demokratické ideály, ale i o rodný jazyk a národní kulturu. Jazyk se stal nejdůležitějším výrazem identifikace národa.

Poezie byla jedním z prvních literárních žánrů, které byly vzkříšeny. Stala se důležitým činitelem kulturního i politického probouzení a už tehdy pociťoval národ za nové pokusy o české písemnictví velkou vděčnost. Lid, který ztratil svou reprezentaci politickou, zbavený svých politických mluvčích, hledal si reprezentaci náhradní a vybíral šiji z těch svých duchovních sil, jež mu zbyly.

Odtud ona poměrně značná váha poezie v našem kulturním životě, zde je vysvětlení jejího kultu a jejího prestyže už v minulém století. Ale hrála významnou úlohu nejen tehdy. Rozkvetla k plné bohatosti také na začátku našeho století a mezi oběma světovými válkami, aby se pak stala nejdůležitějším projevem naší národní kultury v době války, za utrpení a ohrožení národa, a dokázala přes všechna vnější omezení a cenzuru vytvářet hodnoty, jež dávaly lidem sílu a naději. Podstatný podíl na kulturním životě připadá u nás lyrice i po válce, v posledních čtyřiceti letech. Lyrika jako kdyby byla předurčena nejen promlouvat k lidem z největší blízkosti, nejdůvěrněji, ale být i nejhlubším a nejbezpečnějším útočištěm, v němž hledáme útěchu ze strastí, jež se někdy ani neodvažujeme pojmenovat.

Jsou země, kde tuto úlohu útočiště nebo korouhve plní v prvé řadě náboženství a jeho kazatelé. Jsou země, kde národ nachází svůj obraz a svůj osud v katarzích dramat, nebo slyší ve slovech politických vůdců. Jsou země a národy, jež čtou vyjádření svých otázek i odpovědi na ně u duchaplných a moudrých myslitelů, někde tuto úlohu plní novináři a sdělovací prostředky. U nás jako kdyby si duch národa pro svoje vtělení vybíral básníky a dělal z nich své mluvčí. Tato převaha lyriky, myslím, trvá. Básníci, lyrikové, hnětli podobu národního vědomí a vyjadřovali národní aspirace v minulosti a hnětou toto vědomí i dnes. Národ si zvykl chápat věci tak, jak mu je podává jeho básník.

Viděno očima básníka, je to něco úžasného. Ale …

Nemá i tenhle jev svůj rub? Neznamená přemíra lyriky porušení nějaké rovnováhy v kultuře? Připouštím, že v dějinách národů mohou být doby nebo nastat okolnosti, kdy je výhodnější a snazší, nebo dokonce jedině možná výpověďlyrická, se svou schopností vystačit s nápovědí, náznakem a metaforou, zahalit jádro výpovědi, skrýt je před nepovolanými zraky. Připouštím, že řeč lyriky bývala často i u nás, zejména za politické nesvobody, řeci zástupnou, náhradní, řeci z nouze, protože se nejlépe hodila k vyslovování toho, co by se jiným způsobem vyslovit nedalo. Ale přesto mi otázka převahy lyriky už dlouho leží na srdci. Tím spíš, že jsem se sám narodil lyrikem a celý život jsem jím zůstal.

Znepokojuje mě podezření, že onen sklon k lyrice a záliba v ní nemůže nebýt výrazem něčeho, co se snad dá označit jako stav ducha. Lyrismus, jakkoli hluboké může být jeho ponořování do skutečnosti, jakkoli bohaté a mnoho- vrstevné může být jeho vidění věcí a jakkoli závratné jeho objevování a přitom i vytváření vnitřních rozměrů lidství, je především záležitostí smyslů a citu, smysly a cit živí jeho fantazii, ale také naopak smysly a cit jsou jím oslovovány.

K plnosti vnitřního života jedince i k plnosti kultury společnosti je však nutno, aby se na nich vedle smyslů a citu podílely také rozum a vůle. Kultura je neúplná, nejsou-li pěstovány všechny její složky a podoby. Její plnost, zralost i síla, její hodnota pro člověka i společnost je tím větší, čím více duchovních potřeb dokáže uspokojovat.

Neznamená převaha lyrismu, s jeho smyslovostí a citovostí, upozadění sféry rozumové, s její analytičností a skepsí a kritičností? Neznamená dále, že se plně neuplatňuje v kultuře prvek volní s jeho dynamičností a patosem?

Nehrozí takto jednostranně orientované kultuře nebezpečí, že nebude schopna plnit své poslání v plné míře a v plné šíři? Může mít společnost inklinující převážně nebo především k lyrismu vždycky dost sil, aby se uhájila a zajistila si trvání?

Neznepokojuje mě ani tak nebezpečí možného zanedbávání té složky kultury, která se opírá o naše schopnosti rozumové, rozvíjí se z reflexe a nachází svůj výraz v pokud možno objektivním konstatování věcí a jejich vztahů. Tato složka, vyznačující se odstupem od věcí, duševní rovnováhou, neboťprogra- mově nepodléhá ani náladám a pocitům lyrického stavu ducha, ani vášním stavu patetického, nenechává se ukolébávat, ale také nevyráží netrpělivě do útoku za nějakým mravním cílem, má v naší racionalisticko-utilitárně-prak- tické civilizaci dostatečně mohutné kořeny v potřebě vědět, poznat a poznatků využít. Rozvíjí se od renesance se spolehlivou samovolností. Setkává se sice někdy také s neporozuměním a vnějšími překážkami, ale její postavení v naší dnešní kultuře je přitom dominantní, přestože stojí před velkými problémy, neboťmusí hledat nový způsob, jak do naší kultury znovu začlenit svoje pojmové myšlení a dát rozumu novou podobu, vzhledem k tomu, že nemůže zůstat rozumem doby předtechnické. Uvědomuji si, že je stejně důležitá jako obě ostatní, o nichž jsem se zmínil. Přesto jí zde nechci věnovat stejnou pozornost. Už proto, že pro umění, pro krásné písemnictví, není její způsob myšlení, myšlení pojmové, podstatné, zatím co já se chci držet oněch dvou krajních stavů ducha, z nichž může vycházet ve své tvorbě spisovatel a které mají svůj protějšek v postojích čtenářů a posluchačů a skrze ně pak vliv na celkový charakter národní kultury.

Co mě znepokojuje, je možný nebo skutečný nedostatek patosu. Nesetkáváme se dnes s tímto slovem příliš často. A užijeme-li ho tu a tam, pak skoro s ostychem. Připadá nám zvetšelé jako staré kulisy romantického divadla, přežilé, jako kdyby znamenalo pouze špatné, povrchní a neprožité deklamování. Skoro jako kdybychom zapomněli, že jde o dramatický stav tenze, o cílevědomé, energické a odhodlané chtění, prahnutí, nikoli ovšem po nějakých hmotných statcích nebo dokonce statcích spotřebních, nýbrž o prahnutí po spravedlnosti, pravdě. Patos je rysem heroismu, a ten je ochotný strádat, snášet utrpení a je odhodlaný k oběti, bude-li to nutné. Užívám-li slova heroismus, nemám ovšem na mysli ten starý heroismus dějepisů a školních čítanek, heroismus válečný, nýbrž jeho podobu novodobou, heroismus, který nemává zbraněmi, je neokázalý, nenápadný, často úplně tichý, zcivilněný, nechci-li říci civilizovaný, zobcanštělý.

Domnívám se, že kultura je úplná, zralá a schopná trvání a rozvíjení jen tehdy, pokud v ní má své místo patos, pokud mu rozumíme a dovedeme ho ocenit a zejména pokud ho jsme schopni.

Co mě k tomu vede? Patos se svým heroismem je především nemyslitelný a nebyl by tím, čím je, kdyby ho neprovázelo hluboké porozumění věcem, porozumění kritické a všestranné, jiné, než jakého je schopna třebas nejcitli- vější lyrika, nutně nekritická, neboťjí chybí odstup, distance, vždyťvypovídá v podstatě pouze o svém subjektu, a ještě k tomu o subjektu se světem splývajícím, o subjektu, který tvoří s objektem jednotu. Patos by nebyl patosem, kdyby nevyplýval z pochopení podstaty sporu mezi tím, co je, a tím, co být má. Aby společnost byla schopna patosu a aby byla její kultura úplná, musí rozumět své době i jinak než lyrickým způsobem. A není-li schopna patosu, není ochotna bojovat ani přinášet oběti.

Teprve literatura, která má vedle své kultury pojmového myšlení, vedle kultury rozumu nejen svou lyriku, nýbrž také svůj patos, své drama, svou živou tragédii, může dávat dost sil duchovních a mravních ke zvládání úkolů, před něž je společnost stále znovu stavěna. Teprve v umění tragédie vytváří a nachází společnost vzory svých postojů v závažných mravních a politických otázkách a učí se vypořádávat s nimi s důsledností, nezastavovat se uprostřed cesty. Teprve umění tragédie s jejími prudkými střety zájmů a hodnot v nás probouzí, rozvíjí a kultivuje společenskou stránku naší bytosti, činí z nás členy pospolitosti a dává nám příležitost, abychom opustili svou samotu. Teprve umění tragédie, na rozdíl od lyriky, „umění osamělosti4′, tříbí schopnost rozlišovat, co je ze společenského hlediska podstatné a nepodstatné, učí objevovat v porážkách vítězství a ve vítězstvích porážky, vůbec vědět, co je vítězství a co porážka.

Proto bych chtěl, když se dívám kolem sebe a hřeji se v přízni milovníků lyriky, být svědkem nikoli konce tragédie, ale jejího znovuzrození, pro její patetický stav ducha. Pro onen stav rozechvění, když se v nás něco pohnulo a my začínáme chtít to, co považujeme za spravedlivé, za správné a stavíme se proti tomu, co je, ačkoli by být nemélo.

Zatím co lyrický stav ducha je stavem soběstačného jedince, jenž vypovídá o vlastním nitru ztotožňujícím se a splývajícím s objektem, patetický stav tuto jednotu subjektu a objektu nezná. Rodí se z napětí mezi skutečností a mnou, mou představou o tom, jaká by ona skutečnost měla být. Ve svých důsledcích z napětí mezi mocí a rozumem, mezi politikou a morálkou. Lyrický stav mezi tím, co je, a tím, co má být, nerozlišuje. Lyrickému subjektu je lhostejno, zda jeho imaginace je zažehována skutečností nebo fikcí, pravdou nebo přeludem, iluze je pro ni stejně pravdivá, jako pro ni může být skutečnost přeludná. Lyrický stav se nezajímá o tyto rozdíly, nekonfrontuje je ani mezi sebou, ani se sám s nimi necítí konfrontován. Patetické já nejen tyto rozdíly vidí, ale také se s nimi cítí samo konfrontováno, vidí, jak proti sobě stojí dvě alternativy, dvě možnosti, a samo se cítí vtaženo do napětí mezi nimi. Právě toto napětí je uvádí do pohybu. Začátkem onoho pohybuje neklid, nespokojenost, rozhořčení, jeho cílem dosažení nebo nastolení stavu, který se jeví jako rozumný, přirozený, krásný a má podobu práva, spravedlnosti, svobody, lidské důstojnosti.

Na mravní velikosti a smysluplnosti tohoto pohybu nic nemění skutečnost, že se jeho cíl neustále vždy znova vzdaluje a že žádný akord oné harmonie, za níž se patos vrhá, není konečný. Pohyb patosu je obdobou snah naší estetické emoce při vnímání uměleckého díla. I ona vždy znova marně usiluje, aby v plné míře obsáhla a vyčerpala jeho hodnoty ve vší jejich bohatosti a vychutnala jeho strukturu myšlenkovou i formální, pokouší se dosáhnout toho, aby uspokojení a radost z uměleckého díla byly zároveň největší i nepomíjející.

Patos je v každé chvíli v předstihu, nestojí na půdě dneška, živí se jinou potravou, než jsou sladkosti přítomné chvíle, těch se dokáže zříci. Dovede se ovládat, být ukázněný, asketický, a to ve správném smyslu, nikoli totiž proto, že by musel, nýbrž na základě vlastního svobodného rozhodnutí, ví, proč to dělá. Nic z toho není pro něj obtížné. Jen nedovede být netečný a chladný. Bohudík. Neboťjinak by společnost zůstávala na mrtvém bodě a ve slepé uličce, pravda by byla služkou moci, právo nástrojem hrubé síly neboli bezprávím a křivdou. Pravda nevítězila, nevítězí a nebude vítězit bez patosu. Někdy nevítězí dokonce ani za tuto cenu. Ale v tom případě patos činí i z nezdaru, z toho, co by jinak vypadalo jako jakási živelná pohroma, osudová katastrofa, jako konec, něco víc. Ciní z porážky oběť, pozvedá neúspěch na událost, která je součástí většího celku, na událost, která měla a má svůj smysl a plní své poslání jako dílčí pohyb k tomu, čeho má být dosaženo a čeho snad jednou dosaženo bude. Dokud v sobě chováme patos, trvá i naše naděje. Patos není možno porazit, přežívá své porážky. Přežívá je patos jedince i patos národů, s vážností, hrdostí a důstojností. Je povznešený nad neúspěchy. Proto je i vznešený a zároveň i povznášející. Povznešený, vznešený a povznášející i tam, kde by bez něho bylo místo jen pro skleslost a smutek.

Ale teď, když jsem vyslovil, co mi tak dlouho leželo na srdci, a ulevil své starosti, cítím nejen nutkání, ale i právo vrátit se znovu k otázce lyrismu a lyrického stavu ducha.

Mám k tomu řadu důvodů. Narodil jsem se lyrikem a provždy jsem jím zůstal; po celý život jsem se cítil ve své lyrické poloze dobře a bylo by nevděkem to nepřiznat; potřebuji sám před sebou tento svůj základní postoj ospravedlňovat a obhajovat, přestože vím, že v mých básních ěasto zazněly i tóny, které měly svůj patos, vždyťjej může mít i něha, měl jej můj smutek, měly jej mé úzkosti a obavy.

Chci však udělat něco víc. Chci se ujmout lyrického stavu ducha vůbec. Obhájit tento životní postoj a vyzvednout také jeho přednosti, když jsem se poklonil patosu. Zdá se mi to nejen spravedlivé, ale dokonce i svrchovaně časové. Nejen vzhledem k přílišnému důrazu, jaký od dob osvícení naše tradiční kultura kladla na pojmové rozumové myšlení, jež nás (společně s rozvíjením naší volní složky) přivedla k dnešnímu neuspokojivému společenskému stavu, kdy cítíme nutnost změny a hledání jiných možností porozumění našim problémům. Především vzhledem k přebujelému volnímu napětí a tendencím vyhrocovat spory do dramatických střetů, jak jsme toho svědky. Zdá se mi to nutné vzhledem ke stupňující se agresivitě chování ve společenských vztazích, aťuž jde o agresivitu nesenou ještě nějakým patosem, anebo takovou, která je už jenom ničivá a žádného patosu ani není schopna. Chci poukázat na zvláštní přednosti lyrismu právě za těchto okolností v dnešní době.

Neboťzatím co patetický stav ducha hoří netrpělivostí a překypuje úsilím ve snaze vypořádat se s neuspokojivým stavem a zmáhá tento úkol často s dobře míněnou, nicméně jednostrannou přímočarostí, lyrický stav ducha je stavetn bez volního a cílevědomého napětí, je stavem spočinutí, které není ani trpělivé, ani netrpělivé. Stavem zklidněného prožívání hodnot, na nichž člověk staví nejhlubší, nejspodnější, nejzákladnější základy své rovnováhy a schopnosti obývat tento svět, obývat jej oním jediným způsobem, jímž je to možné, totiž poeticky, totiž lyricky, smím-li si dovolit použít tohoto Hólderlinova obratu.

Patos nás pohání a stravuje, je s to nás v našem nepokoji a v naší touze po uskutečnění ideálu hnát k oběti a sebeznicení. Lyrismus nás zadržuje ve svém laskavém objetí. Místo srážky sil prožíváme rozkoš jejich rovnováhy, odsunující je z našeho obzoru a dovolující nám nepociťovat jejich tlak. Místo narážení na hrany světa kolem nás, splýváme s ním v jednotě a ztotožnění.

Patos má vždycky svého protivníka, je výbojný. V lyrickém stavu si člověk stačí sám. A jestliže ve své samotě promlouvá ještě k někomu druhému a oslovuje ho, není to jeho nepřítel. Člověkův protějšek za těchto okolností, aťje to příroda, společnost nebo jiný člověk, jako kdyby byl kusem jeho samého, jen dalším účastníkem lyrické samomluvy. To, co by jinak stálo proti nám, tím se necháváme prostupovat, zatím co i my sami to prostupujeme. Vposloucháváme se do toho, co nás obklopuje, a nacházíme právě tímto způsobem sami sebe. A právě takto a tím dosahujeme největší autentičnosti své identity a největší úplnosti své integrity. A také právě v tomto sebeodevzdávání nacházíme svoje bezpečí.

Patos je aktivní, usiluje o dosažení předsevzatého cíle. V lyrickém stavu nechceme ničeho dosáhnout, prožíváme, co již máme, a oddáváme se přítomnému a jsoucímu, i když tím jsoucím může být i evokace minulosti. Není to z mravní lhostejnosti. Pohybujeme se pouze, nebo spíše tkvíme v jiné rovině, dlíme v jiné poloze myšlení, cítění i chtění, v poloze osobní nezainteresovanosti vůle, nikoli neúčasti, nýbrž nezájmu o výsledky.

Zatím co patos musí vkládat do svého gesta sílu a dokáže být ve své dynamičnosti násilný, jeho protějšek síly nepoužívá. Je nenásilný a nepotřebuje se do mírumilovnosti nutit. Rozevírá svou bezbrannou náruč a jeho gestem je gesto lásky. Nezmítá jím ani nepokoj intelektu, ani vášně, nezávodí s časem. Dokáže svým způsobem plynutí času popřít a ve svých vrcholných okamžicích s časem splynout v jakémsi zastavení, jemuž záleží jen na jediném: aby trvalo.

Lyrický postoj nechce druhé přesvědčovat. Nabízí jim pouze možnost, aby sdíleli to, co cítí a prožívá on sám. Nic více a nic méně. Nejde ani tak daleko, aby zaujímal stanovisko. Chybí mu k tomu odstup, vždyťsplývá s tokem života. A jestliže nezaujímá stanovisko, je tím méně schopen se přít.

Ale snad je možno odvážit se ještě dalšího kroku a nadhodit otázku možného vlivu lyrického stavu ducha například v ekonomice, ekologii anebo politice. Ptát se po možném podílení se lyrického stavu ducha na přetváření člověkova vědomí vůbec, na eventuálních změnách jeho způsobu vnímání a vidění, na oné změně, která je obecně považována za nutnou, mají-li být tradiční způsoby chování, vzhledem k tomu, že nejsou na výši dnešních problémů, nahraženy jinými. Snad je možno položit otázku spolupůsobení lyrismu při eventuálním posunu od pojmového myšlení (das begriffliche Denken) k rozumnému vnímání (vernůnftige Wahrnehmung, Vernunft-Wahrnehmung), když jsme se dostali do stavu, který C.F. Weizsácker (Wege in der Gefahr, str. 258) charakterizuje slovy: „Wir haben unsere Gesellschaft in einer Weise stilisiert, die weder der Wahrnehmung der AfTekte noch der Wahrnehmung der Vernunft entspricht. Die Folge ist eine Desintegration der AfTekte und ein Verstummen der Vernunft”.

Lyrický stav ducha, jakkoli se to může zdát paradoxní, je s to přispívat jako jedna ze sil k tomu, aby se naší civilizaci vrátila rozumnost. Napomáhat například i k tomu, aby technika byla řízena opět rozumem, rozumem ovšem spojeným se životem a s přírodou jiným způsobem než pomocí racionálních abstrakcí, tedy rozumem, který by byl jiný než náš nynější racionálně utilitární rozum pojmového myšlení.

Nabízí se i jako mírnící činitel našeho výbojného a dynamického ducha, naší tolik se prosazující vůle. Dynamismus a vůle, spolu s kulturou pojmového myšlení, byly sice zdrojem našeho technického a hospodářského rozmachu, našich průmyslových revolucí a tím i mocenského vlivu ve světě. Ale přinesly s sebou i naše dnešní potíže a záporné stránky, jež vystupují do popředí tím více, čím větších úspěchů tento dynamický a výbojný duch dosahuje. Je to duch podrobování a dobývání, duch ovládání přírody zrovna tak jako lidí a národů a celých civilizací, duch racionalizované vůle po moci nad přírodou i nad lidmi. Je to onen stav ducha, kdy se naše vůle chce zmocňovat, čeho se dá, obohacovat se a hromadit statky, místo abychom se z věcí těšili bez toho, že bychom si je podřídili. Toto příliš silné chtění může být vyvažováno a drženo na uzdě a vedeno k postojům jiným než výbojně kořistnickým právě lyrickým postojem nezainteresovanosti vůle. Neděje-li se tak, zvrhá se ve chtivost. Jak napsal E.F. Schumacher (v knize Small is beautiful, str. 27): “A man driven by greed or envy loses the power of seeing things as they really are, or seeing things in their roundness and wholeness, and his very successes become failures. If whole societies become infected by these vices, they may indeed achieve astonishing things but they become increasingly incapable of solving the most elementary problems of everyday existence”.

Není vedle nutnosti nové hodnotové orientace, jak o ní mluví různí autoři, i lyrický stav ducha, spočívající ve ztotožňování se s přírodou a se svétem kolem nás vůbec, jedním z možných zdrojů vnitřní proměny člověka a tím i jednou z cest, jak jej vyvést z jeho neudržitelného postavení samozvaného pána, který se staví mimo přírodu, nad ni a proti ní? Není lyrický stav ducha jednou z možností jak překonat pojímání přírody jako véci dané člověku, jeho síle a dovednosti, aby sejí zmocňoval, nakládal s nijako se svou kořistí a sytil svou nenasytitelnou chtivost? A není konečné lyrický stav ducha také oním Heideg- gerem požadovaným obratem ve vztahu k jsoucnu? Obratem spočívajícím v tom, že necháme jsoucno být tím, čím je, aby nás posléze samo oslovilo a ukázalo se nám ve své smysluplné podstatě tak, že se nám stane srozumitelné?

Je možno nevidět, že lyrismus ztělesňuje protipól kultu síly a moci a nabízí se zcela samozřejmě jako jeden z korektivů tendence řešit společenské otázky mocenskými prostředky a mocenskými boji, mocí technickou, mocí ekonomickou, mocí organizační, mocí politickou, mocí fyzickou, mocí, která je v každém případě vždycky jen produktem neúplného pochopení, „ein Produkt unvollstándiger Einsicht”? A právě tak je možno jej stavět proti modlářství práce a výkonu, proti posedlosti myšlenkou ovládání a využívání přírody i lidí. Zvláště když moc často povyšuje výkonnost a zdokonalování svých mocenských systémů na nejpřednější zájem, i když jde o systémy, jež z vyššího hlediska vůbec nejsou funkční a konají své dílo za cenu ztrát na důstojnosti člověka, na hodnotách nejen hmotných, ale i mravních, za cenu ztráty harmonie v člověku i harmonických vztahů mezi lidmi.

Mnoho lidí je si dobře vědomo, že onen vystupňovaný stav chtění, dobývání, expanze a exploatace musí být spoután a držen na uzdě, nemají-li škody, které z něho vzcházejí jako jeho jakýsi negativní sociální produkt, převážit užitek. Ale uvědomovat si tyto skutečnosti, pouze o nich vědět, je málo. Aby došlo k nějaké podstatné změně a k podstatnému odvratu od snahy stupňovat moc a rozvíjet ji do všech směrů a ke škodě člověka, je třeba změny stavu ducha, změny ve vědomí, anebo, jak to bylo kdysi krásně řečeno, „revoluce hlav a srdcí”.

Nechci se pokoušet činit z lyrismu nebo dokonce jen z lyriky politickou sílu nebo nástroj politiky a zbavovat poezii a vůbec umění jeho nejvlastnějšího, specifického a ničím nezastupitelného poslání ani podřizovat toto jeho poslání zájmům jiným. Nicméně se domnívám a odvažuji se to říci, že lyrický stav ducha je něčím, co daleko přesahuje oblast lyriky i poezie a umění vůbec. Tam, kde by se výrazně projevoval, mohl by vtiskovat kultuře a vůbec všem institucím společnosti nové příznivé rysy. Napomáhal by nutné celkové změně vědomí, procesu, k němuž dnes už u mnoha lidí dochází, nejvíce u umělců, nejméně u těch, kdo se nechali vtáhnout do mocenské hry politiky. Plnil by svým způsobem podobnou úlohu jako mystická meditace — ostatně lyrice vždycky blízká, jenomže je oproti lyrice prostředkem nebo nástrojem příliš výlučným. Působil by k tomu, aby lidé získávali schopnost a ochotu „den Willen still werden zu lassen und das Licht zu sehen, das sich erst bei still gewordenem Willen zeigt”. Byl by jako mystická meditace „eine Schule der Wahrnehmung, des Kommenlassens der Wirklichkeit” (C.F. Weizsácker).

Každá kultura toto poslání plnit nemůže. Skládat naděje pouze v kulturu jako takovou, v kulturu ve smyslu pěstování a dalšího tříbení toho, co jsme převzali z minula, vedlo by ke zklamání. Byla by to pořád ta tradiční kultura vůle a starého rozumu. I kdybychom zapomněli, že naše kultura dokázala být nejen nesnášenlivá (přestože panuje přesvědčení, že ke kultuře patří i tolerance, snášenlivost), že dokázala být utlačivá, arogantní a mesianistická, být pro mnohé důležité hodnoty necitlivá, mnohým nerozumět a naopak vnucovat leccos, co hodnotou není, nemůžeme nevidět, že legitimita tradičních jejích hodnot je víc než otřesena.

Toto poslání může dnes plnit jen kultura vycházející z podstatně modifikovaného stavu vědomí, z jiného stavu ducha. A zde právě vidím velkou příležitost a velkou úlohu lyrismu a lyriky, onoho stavu ducha, pro nějž je příznačné ztotožňování se se světem, vciťování, sympatie, soucítění a nezainteresovanosti vůle. Její moudrost, přestože by v ní hrál základní úlohu tak neracionální element, jako je láska, nemusela by být o nic menší než moudrost kultury, s níž máme co činit dnes.

Chce se mi dokonce prohlásit, že teprve ona by byla onou šťastnou a vskutku blahodárnou kulturou, jakou by měla být.

A zde, když to říkám, vtírá se mi do mysli ještě jedna otázka, která se mi v této chvíli zdá skoro jen otázkou řečnickou: Není patos živen a hnán právě vizí tohoto šťastného a blahodárného porozumění věcem a jejich moudrého uspořádání na podkladě sympatie a soucítění? V duchu „lásky jako vidoucího postoje duše, rušícího boj o existenci”, jak to formuloval C.F. Weizsácker? Není patos pokusem o překročení vlastního stínu a pokusem o návrat do Arkadie, kde rozumné, spravedlivé a přirozené je totožné se skutečností? Není patos jen pokusem o návrat k idyle, to jest ke stavu, kdy nad sebou nepociťujeme žádnou cizí moc a mizí rozpor mezi tím, co je, a tím, co být má, ke stavu, kdy rozum a moc, mravnost a politika mohou spolu sedět u jednoho stolu? A není nakonec ztracený ráj, o nějž patos usiluje, světem lyrismu? Není právě poezie, lyrika, jedním z hlavních strůjců a tlumočníků vize tohoto ráje?

Při těchto větách jsem v pokušení stát se z lyrika rodem – lyrikem z přesvědčení, lyrikem volbou.

Jaroslav Seifert – Nobel Lecture

English

Czech

Nobel Lecture, December 1984

(Translation)

On the Pathetic and Lyrical State of Mind

I am often asked, particularly by foreigners, how one can explain the great love of poetry in my country: why there exists among us not only an interest in poems but even a need for poetry. Perhaps that means my countrymen also possess a greater ability to understand poetry than any other people.

To my way of thinking, this is a result of the history of the Czech people over the past 400 years – and particularly of our national rebirth in the early 19th Century. The loss of our political independence during the Thirty Years’ War deprived us of our spiritual and political elite. Its members – those who were not executed – were silenced or forced to leave the country. That resulted not only in an interruption of our cultural development, but also ih a deterioration of our language. Not only was Catholicism reinstituted by force, but Germanization was imposed by force as well.

By the early 19th Century, however, the French Revolution and the Romantic period were exposing us to new impulses and producing in us a new interest in democratic ideals, our own language, and our national culture. Our language became our most important means of expressing our national identity.

Poetry was one of the first of our literary genres to be brought to life. It became a vital factor in our cultural and political awakening. And already at that early stage, attempts to create a Czech tradition of belles-lettres were received with vast gratitude by the people. The Czech people, who had lost their political representation and had been deprived of their political spokesmen, now sought a substitute for that representation, and they chose it from among the spiritual forces that still remained.

From that comes the relatively great importance of poetry in our cultural life. There lies the explanation of our cult of poetry and of the high prestige it was already being accorded during the last century. But it was not only then that poetry played an important role. It burst into sumptuous blossom in the beginning of this century as well and between the two world wars – subsequently becoming our most important mode of expressing our national culture during World War II, a time of suffering for the people and of threat to the very existence of the nation. Despite all external restrictions and censorship, poetry succeeded in creating values that gave people hope and strength. Since the war, too – for the past 40 years – poetry has occupied a very important position in our cultural life. It is as though poetry, lyrics were predestined not only to speak to people very closely, extremely intimately, but also to be our deepest and safest refuge, where we seek succor in adversities we sometimes dare not even name.

There are countries where this function of refuge is filled primarily by religion and its clergy. There are countries where the people see their image and their fate depicted in the catharsis of drama or hear them in the words of their political leaders. There are countries and nations that find their questions and the answers to them expressed by wise and perceptive thinkers. Sometimes, journalists and mass media perform that role. With us, it is as though our national spirit, in attempting to find embodiment, chose poets and made them its spokesmen. Poets, lyrists shaped our national consciousness and gave expression to our national aspirations in bygone times – and they are continuing to shape that consciousness to this very day. Our people have become accustomed to understanding things as presented to them by their poets.

Seen with the poet’s eyes, this is something wonderful. But … is there not a dark side to this phenomenon as well? Does not a surfeit of poetry mean a perturbation in the equilibrium of culture? I admit that periods can exist in the histories of peoples, or circumstances can arise, in which the poetic rendering is the most suitable, the most simple, or perhaps even the only possible – with its ability to merely suggest, to use allusion, metaphor, to express what is central in a veiled manner, to conceal from unauthorized eyes. I admit that the language of poetry has often been, even with us – particularly in times of political restriction – a deputy language, a substitute language, a language of necessity, in as much as it has been the best means of expressing what could not be said in any other way. But even so, the dominant position of poetry in our country has long been on my mind – all the more so because I myself was born to be a poet and have remained a poet all my life.

I am worried by the suspicion that this inclination toward, and love of, poetry, lyrics may not be an expression of anything other than what might be described as a state of mind. However deeply lyricism might be able to penetrate in reality, however rich and multifaceted its ability to see things, and however prodigiously it can reveal and at the same time create inner dimensions of human nature, it remains nevertheless a concern of the senses and the emotions; senses and emotions nourish its imagination – and vice versa: it speaks to senses and emotions.

Doesn’t a dominant position for lyricism, with its emphasis on sense and emotion, mean that the sphere of reason, with its emphasis on analysis, its skepticism and criticism, is pushed into the background? Doesn’t it mean, moreover, that the will, with its dynamism and pathos, cannot achieve its full expression?

Isn’t a culture of such one-sided orientation in danger of being unable to fulfil its responsibility completely? Can a society that mainly, or primarily, inclines toward lyricism always have strength enough to defend itself and ensure its continued existence?

I am not really very worried about the danger of possibly neglecting that element of culture that is based on our rational powers, that arises from reflection and finds expression in the most objective possible depiction of the essences and interrelations of things. That rational element – which is characterized by its distance to things, by mental balance, for it is programmatically not dependent on either the moods and feelings of the lyrical state of mind or on the passions of the state of pathos – that rational element does not allow itself to be lulled into tranquillity; but neither does it hurl itself impatiently at any moral target: in our rationalistically utilitarian, practical civilization, it is sufficiently strongly rooted in our need to know, to acquire knowledge and use it. This rational element has evolved continuously and spontaneously ever since the Renaissance. Admittedly, it is also unsympathetically received sometimes and now and then encounters external obstacles, but its position in our modern culture is nevertheless dominant even so – despite the fact that it faces great problems, for it must seek a new way of reincorporating its conceptual thinking into our culture and of giving reason a new form, since it cannot remain the reason of pre-technological times. I am aware that this element is just as important as both the others I have already mentioned. Despite that, however, I do not wish to devote to it here the same degree of attention, since its way of thinking – conceptual thinking – is not essential to art or literature. I wish to confine myself to the two extreme states of mind from which an author can commence creating. They have their counterparts in the readers’ and spectators’ attitudes and, through them, affect in their turn the character of our entire national culture.

What worries me is a possible or real lack of pathos. These days, we do not encounter that word very often. And if we use it now and then, we do so almost with a certain timidity. It strikes us as old and moth-eaten, like old sets from a theater of the Romantic era – out of date, as though it only stood for poor, superficial, and emotionless declamation. It is almost as though we had forgotten it describes a dramatic state of tension, a purposeful, energetic, and resolute will, a yearning – not for any material possessions or even consumer goods, of course, but rather for justice, for truth. Pathos is a characteristic of heroism, and heroism is willing to endure torment and suffering, prepared to sacrifice itself if necessary. If I use the word heroism, I am not, of course, referring to the old heroism of the history books and school readers, heroism in war, but rather to its contemporary form: a heroism that does not brandish weapons, a heroism without ostentatiousness, discreet, often utterly silent, civil, indeed civilized, a heroism that has become civic.

I believe that a culture is complete, mature, and capable of enduring and developing only if pathos has a place in it, if we understand pathos and can appreciate it – and especially if we are capable of it.

What leads me to these thoughts? Pathos with its heroism is, above all, unthinkable and would not be what it is if it were not accompanied by a profound understanding of the essences of things, a critical and all-round understanding, an understanding quite other than that which even the most sensitive poetry is capable of; poetry – lyrics – is necessarily uncritical, for it lacks distance, speaking as it does actually only about its own subject – a subject, moreover, that flows with its time, a subject that forms a unity with its object. Pathos would not be pathos if it did not derive from an insight into the character of the conflict between that which is and that which ought to be. For society to be capable of pathos and for its culture to be complete, it must also understand its time in another manner besides the lyrical. And if it is not capable of pathos, then it is not prepared either for struggle or for sacrifice.

Only literature – which, in addition to its conceptual-thinking culture, its culture of reason, not only has its lyrics but also its pathos, its drama, its living tragedy – can provide sufficient spiritual and moral strength to overcome the problems that society is constantly having to confront. Only in the art of tragedy does society create and find patterns for its attitudes in essential moral and political issues; it learns there how to deal with them consistently, without halting halfway. Only the art of tragedy, with its violent conflicts between interests and values, awakens, develops, and cultivates within us the social aspect of our essence; it makes us members of the community and gives us the opportunity to leave our solitude. Only the art of tragedy – which, unlike Iyrics, that “art of solitude,” refines our ability to discriminate between that which is essential and that which is inessential from a societal viewpoint – only the art of tragedy teaches us to see victories in defeats and defeats in victories.

Therefore, as I look around me and warm myself in the good will of poetry lovers, I would like to bear witness, not to the death of tragedy, but to its rebirth as a result of its pathetic state of mind, its state of powerful emotions, since something has been set into motion within us, and we are beginning to want that which we regard as just and to oppose that which exists though it should not.

While the lyrical state of the mind is a state in an independent individual, which testifies to its own innermost self, which agrees and coincides with the object, the pathetic state does not sense this unity between subject and object. It is born of a tension between reality and the ego, my conception of how this reality ought to be – and thus of a tension between power and reason, between politics and morals. The lyrical state does not discriminate between that which is and that which ought to be. It is indifferent to the lyrical subject, whether its imagination is fired by reality or by fiction, by truth or by figments of the imagination; the illusion is as real to the imagination as reality can be illusory to the imagination. The lyrical state is not interested in these differences; it neither confronts them with each other nor regards itself as confronted by them. The pathetic ego not only sees these differences, but also perceives itself as confronted by them; it sees how two alternatives, two possibilities, stand arrayed against each other, and it sees itself as drawn into the tension between them. This very tension sets the ego into motion. That motion is initiated by worry, discontentment, vexation; its goal is to achieve or to introduce a state that appears rational, natural, pleasant – and that bears the form of right, justice, freedom, and human dignity.

The moral greatness and meaningfulness of this motion of pathos in no way alters the fact that its goal is constantly and continuously becoming more distant and that no chord in the harmony so heatedly sought after by pathos is final. The motion of pathos is a counterpart to our esthetic emotion’s intentions when we experience a work of art. This emotion, too, constantly strives, in vain, to achieve a broad and exhaustive understanding of the values of the work in all their richness and to enjoy the thought structure and form of the work; it attempts to achieve a state in which one’s satisfaction with the work of art and one’s joy in experiencing it are simultaneously maximal and lasting.

Pathos is always one step ahead; it does not stand on today’s ground; it feeds on other nourishment than the nectar of the present moment; that, it can forego. It can control itself, be disciplined, ascetic in the proper sense of the word – by no means because it must, but rather on the basis of its own free decision; it knows why it does so. Nothing in this is difficult for it. It is quite simply incapable of being indifferent and cold. And thank goodness for that. For otherwise society would become deadlocked, find itself in a cul-de-sac; truth would become handmaiden to power, right the tool of brute strength – or, rather, it would become rightlessness and injustice. Truth has not prevailed, does not prevail, and will not prevail without pathos. Sometimes, it does not prevail even at that price. But in that case, pathos does transform even a failure – that which would otherwise look like a natural calamity, a fateful event, the end – into something more. Of a defeat it makes a sacrifice; it elevates the failure and makes it an event that is a component of a larger entity, an event that had and that retains its meaning and fulfil its task as a partial movement toward the goal that was to be achieved and that, perhaps, one day will be achieved. So long as we retain our pathos, we retain our hope. Pathos cannot be finally conquered; it survives its setbacks. Both the pathos of the individual and the pathos of the nations survive setbacks, with seriousness, pride, and dignity. It is above failure. Thus, it is simultaneously elevated and elevating. Above, elevated, and elevating even where, without pathos, there would be scope only for discouragement and grief.

But now that I have said that, which has been on my mind for a long time, and been freed of my concerns, I feel not only compelled but also entitled to return to the matter of lyricism and the lyrical state of mind.

I have several reasons for doing so. I was born to be a lyrist, and I have always remained one. All my life, I have enjoyed my lyrical frame of mind, and it would be ungracious of me not to admit it. I have a need to justify and defend to myself this basic attitude of mine, despite the fact that I know my poems have often sounded tones that have borne their own pathos. After all, even tenderness can have pathos; my grief has had it; my anxiety and fear likewise.

But I want to do something more. I want to deal with the lyrical state of mind. I want to defend this attitude toward life, emphasize its advantages, too, now that I have professed my respect for pathos. To do so seems to me not only just, but also downright necessary. And here I am referring not merely to the altogether excessive emphasis that, ever since the Enlightenment, our traditional culture has accorded rational conceptual thinking, which (together with the development of our will) has brought us to the unsatisfactory societal state of today, where we feel it necessary to have change and necessary to seek new ways of understanding our problems – primarily in light of the vast exertion of will and tendency toward an exacerbation of disputes into dramatic conflicts that we are witnessing. This seems to me necessary in view of the increasing behavioral aggressiveness present in interrelationships within society – whether it is aggressiveness still borne by some manner of pathos or the kind that is merely destructive in itself and incapable of any pathos at all. I want to elucidate the special advantages of Iyricism under these very circumstances in our time.

For while the mind in a state of pathos burns with impatience and seethes with fervor in its endeavor to master an unsatisfactory situation and often succeeds in so doing with a well-intentioned but nevertheless one-sided straightforwardness, the lyrical state is a state without exertion of will or determination; it is a state of serenity that is neither patient nor impatient, a state of quiet experiencing of those values upon which man bases the most profound, the most fundamental, and the most essential foundations of his equilibrium and of his ability to inhabit this world, to inhabit it in the only possible manner, i.e., poetically, lyrically, to borrow from Hölderlin.

Pathos incites us and corrodes us; it is capable – in our anxiety and in our longing to realize ideals – of driving us to sacrifice and to self-destruction. Lyricism keeps us in its affectionate embrace. Instead of perceiving a conflict between forces, we feel a pleasurable joy in their equilibrium, which pushes them away from our horizon and results in our not feeling their weight. Instead of bumping into the edges of the world around us, we flow along with it to unity and identification.

Pathos always has its opponents: it is aggressive. In his lyrical state, man needs no one else. And if, in his loneliness, he does turn to someone and speaks to him, that other person is not his enemy. Under these circumstances, it is as though one’s counterpart – whether nature, society, or another human being – were a part of himself, merely another participant in the lyrical monologue. That which otherwise would oppose us we let suffuse us, while at the same time we ourselves suffuse it, too. We listen intently to that which is around us, and in that very way, we find ourselves. And thereby we achieve our most genuine identity and most complete integrity. And it is in this very surrendering of ourselves that we find our security.

Pathos is active: it strives to reach a set goal. In our lyrical state, we do not want to achieve anything; we experience what we already have and we devote ourselves to the present and the existing, even if the existing can also consist of an evocation of the past. This is not a result of moral indifference. We merely move on – or, rather, at present occupy – a different plane; we are in a different position in regard to thinking, feeling, and wishing: a position in which the will is not committed. It is by no means absent, mind you just not interested in achieving results.

While pathos must put strength into its gestures and has the capability of being violent, dynamic as it is, its counterpart – poetry, lyrics – does not employ strength. It is non-violent and does not need to force itself into placidity. It opens its defenceless embrace, and that gesture is one of love. It is harried neither by the concerns of the intellect nor by those of the passions; it does not compete with time. It has the ability to contest, as it were, the passage of time and in its best moments, conjoin with time in a sort of motionlessness where only one thing matters: that it be lasting.

The lyrical attitude has no desire to convince others. It merely offers them an opportunity to partake of that which it feels and experiences itself. No more and no less. It does not even go so far as to take a stand. It lacks distance; it conjoins, after all, with the flow of life. And if it takes no stand, it is all the less capable of becoming involved in disputes.

But perhaps one might dare take yet another step and pose a question concerning the possible influence of the lyrical state of mind on economy, ecology, or politics, for example. Additionally, one might ask about the participation of the lyrical state of mind in the upheaval in human consciousness in general, in possible changes in mankind’s ways of seeing and perceiving (changes generally regarded as necessary); one might ask whether traditional patterns of behavior (considering that they are not equal to the problems of today) should be replaced by other ones. One might pose the question of lyricism’s role in a possible shift from conceptual thinking (das begriff liche Denken) to rational perception (vernünftige Wahrnehmung, Vernunft-Wahrnehmung) now that we have entered that state that C.F. Weizsäcker (Wege in der Gefahr, p 258) characterizes thus: “Wir haben unsere Gesellschaft in einer Weise stilisiert, die weder der Wahrnehmung der Affekte noch der Wahrnehmung der Vernunft entspricht. Die Folge ist eine Desintegration der Affekte und ein Verstummen der Vernunft.”

The lyrical state of mind is capable, however paradoxical it may seem, of contributing as one of several forces to the return of wisdom to our civilization – capable, for example, of contributing to technology’s being guided anew by reason: a reason that, naturally, is united with life and with nature in ways other than through rational abstractions – in other words, a reason that would differ from our present, rational, utilitarian reason and its conceptual thinking.

It also presents itself as a moderating factor in our aggressive and dynamic spirit, in our so highly self-assertive will. Admittedly, our dynamism and will – in the context of our conceptual-thinking culture – were the sources of our technological and economic advancement, of our industrial revolutions, and thereby also of our power and influence in the world. But that spirit has also brought with it the problems and other negative aspects of our time, which, the greater the successes achieved by that dynamic and aggressive spirit, move more and more into the foreground. It is a spirit of subjugation and conquest, a spirit desirous of ruling over nature as well as over men, nations, and entire civilizations, a spirit of rationalized will to power over nature and people. It is a state of mind in which our will strives to become lord over everything it can, to gain riches and possessions, instead of allowing us to find joy in things without bringing them under our sway. This far-too-powerful will can be balanced and bridled and led to other attitudes than the aggressively rapacious precisely through the agency of the Iyrical state of the non-committed will. As E. F. Schumacher wrote (in his book Small Is Beautiful, p 27): “A man driven by greed or envy loses the power of seeing things as they really are, or seeing things in their roundness and wholeness, and his very successes become failures. If whole societies become infected by these vices, they may indeed achieve astonishing things, but they become increasingly incapable of solving the most elementary problems of everyday existence.”

Is it not so that, in addition to the need for new values that various writers speak of, the lyrical state of mind, which is rooted in identification with nature and the world around us, is also one of the possible sources of an inner change in man and thereby, too, one of the ways that can lead man out of his untenable position as a self-designated ruler who places himself outside nature, above it and against it? Is not the Iyrical state of mind a possible instrument for overcoming the idea that nature is something that has been given to man, given to man’s strength and competence so that he may make himself lord over nature, treating it as his prey and using it to satisfy his insatiable possessive instinct? And is not the lyrical state of mind ultimately the change in our relationship to life demanded by Heidegger? A change that means we allow life to be what it is so that, in the end, it will speak to us itself and reveal itself to us in its meaningful essence in such a manner as to make it comprehensible to us?

Can one fail to see that lyricism is the diametric opposite to the cult of strength and power and, in an utterly natural manner, offers itself as a corrective to our tendency to resolve society’s problems by forcible means and through power struggles, through technological, financial, organizational, political, and physical power – power that, in any case, is ultimately merely a product of incomplete insight («ein Produkt unvollständiger Einsicht»)? And in precisely the same way, one can place it in contrast to our worship of work and performance, to our obsession with the idea of ruling and exploiting nature and people, particularly since power often elevates the efficiency and gradual perfecting of its power systems to issues of the greatest importance, even when what is involved are systems that, from the most exaltedly objective viewpoint, are not at all functional and that achieve their tasks only at the cost of losses in human dignity and losses not only in material but also in moral terms – and at the cost of loss of harmony within man himself and of harmonious relationships among people.

Many people are well aware that this ever more powerful possessive instinct, this ever stronger emphasis on conquest, expansion, and exploitation, must be fettered and bridled in order that the damage resulting as its negative social product does not become greater than the advantages. But it is not enough to be aware of these circumstances, to know of their existence. If there is to be a fundamental change – and a fundamental change, of course, away from our striving to increase our power and develop it in every direction – to man’s detriment – then a change in our consciousness is called for, a change in our mental set. As it was once expressed so beautifully, what is needed is a “revolution of the mind and the heart”.

I do not wish to try making lyricism, or more over lyrics, into a political force or a political tool and deprive poetry – or art generally, for that matter – of its true, specific, and irreplaceable purview, nor do I wish to subordinate that purview to other interests. Nevertheless, I feel – and I make so bold as to state – that the lyrical state of mind is something that far transcends the boundaries of lyrics and poetry – or, indeed, of art itself. Where it could manifest itself actively, it would be able – in a new and positive manner – to make its mark on culture and on all societal organizations in general. It would contribute to a necessary, thoroughgoing transformation of the consciousness, a process already underway in many people today, most in artists, least in those who have allowed themselves to be drawn into the power game of politics. In its way, it would be able to fill a function akin to that of mystical meditation – which, incidentally, has always been close to lyrics, but, which, compared to lyrics, is too exclusive a means or instrument. It would contribute to people’s acquiring the ability and the desire to “den Willen still werden zu lassen und das Licht zu sehen, das sich erst bei still gewordenem Willen zeigt.” Like mystical meditation, it would be “eine Schule der Wahrnehmung, des Kommenlassens der Wirklichkeit” (C.F. Weizsäcker).

Not all cultures can manage this task. Pinning one’s hopes on culture, as such, alone – culture in the sense of cultivating and further refining that which we have taken over from the past – would lead to disappointment. It would still be the same, traditional culture of the will and the old reason. Even if we were to forget that our culture could have been not merely intolerant (despite the fact that there reigns in it a conviction that tolerance also belongs to culture), that it could have been repressive, arrogant, and messianic, that it could have been insensitive to numerous important values, lack understanding for many values, and, on the other hand, impose upon people a great deal that is of no value at all, we could not help but see that the legitimacy of this culture’s traditional values has been more than undermined.

Today, this task can be achieved only by a culture whose point of departure is an essentially modified state of consciousness, another state of mind. And right here, I see a great opportunity and a great task for lyricism and lyrics, for this state of mind, which is distinguished by identification with the world, by empathy, by sympathy, and by an uncommitted will. Despite the fact that so irrational an element as love would play an essential role in such a culture, the wisdom in that culture would in no way have to be less than the wisdom in the culture we have to cope with today.

I would even like to declare that only then would it become the happy culture, truly rich in blessings, that it ought to be.

And now, as I say that, yet another question comes to my mind – a question that, at this moment, strikes me as merely rhetorical: is it not true that pathos lives on, and is fueled by, precisely the vision of this happy understanding of things and of how wisely they are ordered on the basis of mutual sympathies? In a spirit of “love as the seeing state of mind that abolishes the struggle for existence,” as C.F. Weizsäcker formulated it? Is not pathos an attempt to reach outside one’s own shadow and an attempt to return to Arcadia, where the rational, the just, and the natural are identical to reality? Is not pathos merely an attempt to return to the idyll – that is, to a state in which we know no foreign power over us and where the conflict between that which is and that which ought to be disappears, a state where reason and power, morals and politics, can sit down at the same table together? And finally, is the lost paradise sought by pathos not the world of lyricism? Is not poetry itself, lyrics, one of the foremost creators and interpreters of the vision of that paradise?

As I write this, I am tempted to wish that, instead of having been a lyrist by birth, I could become one by conviction: a lyrist by my own choice.

Jaroslav Seifert – Other resources

Links to other sites

On Jaroslav Seifert from Pegasos Author’s Calendar

Jaroslav Seifert – Poetry

Autobiography

Sometimes

when she would talk about herself

my mother would say:

My life was sad and quiet,

I always walked on tip-toe.

But if I got a little angry

and stamped my foot

the cups, which had been my mother’s,

would tinkle on the dresser

and make me laugh.

At the moment of my birth, so I am told,

a butterfly flew in by the window

and settled on my mother’s bed,

but that same moment a dog howled in the yard.

My mother thought

it a bad omen.

My life of course has not been quite

as peaceful as hers.

But even when I gaze upon our present days

with wistfulness

as if at empty picture frames

and all I see is a dusty wall,

still it has been so beautiful.

There are many moments

I cannot forget,

moments like radiant flowers

in all possible colours and hues,

evenings filled with fragrance

like purple grapes

hidden in the leaves of darkness.

With passion I read poetry

and loved music

and blundered, ever surprised,

from beauty to beauty.

But when I first saw

the picture of a woman nude

I began to believe in miracles.

My life unrolled swiftly.

It was too short

for my vast longings,

which had no bounds.

Before I knew it

my life’s end was drawing near.

Death soon will kick open my door

and enter.

With startled terror I’ll catch my breath

and forget to breathe again.

May I not be denied the time

once more to kiss the hands

of the one who patiently and in step with me

walked on and on and on

and who loved most of all.

“Autobiography” from The Poetry of Jaroslav Seifert

Translated from the Czech by Ewald Osers

Edited by George Gibian

Copyright © 1998 by Ewald Osers and George Gibian

Used by permission of Catbird Press

All rights reserved

An Umbrella from Piccadilly

If you’re at your wits’ end concerning love

try falling in love again —

say, with the Queen of England.

Why not!

Her features are on every postage stamp

of that ancient kingdom.

But if you were to ask her

for a date in Hyde Park

you can bet that

you’d wait in vain.

If you’ve any sense at all

you’ll wisely tell yourself:

Why of course, I know:

it’s raining in Hyde Park today.

When he was in England

my son bought me in London’s Piccadilly

an elegant umbrella.

Whenever necessary

I now have above my head

my own small sky

which may be black

but in its tensioned wire spokes

God’s mercy may be flowing like

an electric current.

I open my umbrella even when it’s not raining,

as a canopy

over the volume of Shakespeare’s sonnets

I carry with me in my pocket.

But there are moments when I am frightened

even by the sparkling bouquet of the universe.

Outstripping its beauty

it threatens us with its infinity

and that is all too similar

to the sleep of death.

It also threatens us with the void and frostiness

of its thousands of stars

which at night delude us

with their gleam.

The one we have named Venus

is downright terrifying.

Its rocks are still on the boil

and like gigantic waves

mountains are rising up

and burning sulphur falls.

We always ask where hell is.

It is there!

But what use is a fragile umbrella

against the universe?

Besides, I don’t even carry it.

I have enough of a job

to walk along

clinging close to the ground

as a nocturnal moth in daytime

to the coarse bark of a tree.

All my life I have sought the paradise

that used to be here,

whose traces I have found

only on women’s lips

and in the curves of their skin

when it is warm with love.

All my life I have longed

for freedom.

At last I’ve discovered the door

that leads to it.

It is death.

Now that I’m old

some charming woman’s face

will sometimes waft between my lashes

and her smile will stir my blood.

Shyly I turn my head

and remember the Queen of England,

whose features are on every postage stamp

of that ancient kingdom.

God save the Queen!

Oh yes, I know quite well:

it’s raining in Hyde Park today.

“An Umbrella from Piccadilly” from The Poetry of Jaroslav Seifert

Translated from the Czech by Ewald Osers

Edited by George Gibian

Copyright © 1998 by Ewald Osers and George Gibian

Used by permission of Catbird Press

All rights reserved

Fragment of a Letter

All night rain lashed the windows.

I couldn’t go to sleep.

So I switched on the light

and wrote a letter.

If love could fly,

as of course it can’t,

and didn’t so often stay close to the ground,

it would be delightful to be enveloped

in its breeze.

But like infuriated bees

jealous kisses swarm down upon

the sweetness of the female body

and an impatient hand grasps

whatever it can reach,

and desire does not flag.

Even death might be without terror

at the moment of exultation.

But who has ever calculated

how much love goes

into one pair of open arms!

Letters to women

I always sent by pigeon post.

My conscience is clear.

I never entrusted them to sparrowhawks

or goshawks.

Under my pen the verses dance no longer

and like a tear in the corner of an eye

the word hangs back.

And all my life, at its end,

is now only a fast journey on a train:

I’m standing by the window of the carriage

and day after day

speeds back into yesterday

to join the black mists of sorrow.

At times I helplessly catch hold

of the emergency brake.

Perhaps I shall once more catch sight

of a woman’s smile,

trapped like a torn-off flower

on the lashes of her eyes.

Perhaps I may still be allowed

to send those eyes at least one kiss

before they’re lost to me in the dark.

Perhaps once more I shall even see

a slender ankle

chiselled like a gem

out of warm tenderness,

so that I might once more

half choke with longing.

How much is there that man must leave behind

as the train inexorably approaches

Lethe Station

with its plantations of shimmering asphodels

amidst whose perfume everything is forgotten.

Including human love.

That is the final stop:

the train goes no further.

“Fragment of a Letter” from The Poetry of Jaroslav Seifert

Translated from the Czech by Ewald Osers

Edited by George Gibian

Copyright © 1998 by Ewald Osers and George Gibian

Used by permission of Catbird Press

All rights reserved

To Be a Poet

Life taught me long ago

that music and poetry

are the most beautiful things on earth

that life can give us.

Except for love, of course.

In an old textbook

published by the Imperial Printing House

in the year of Vrchlický’s death

I looked up the section on poetics

and poetic ornament.

Then I placed a rose in a tumbler,

lit a candle

and started to write my first verses.

Flare up, flame of words,

and soar,

even if my fingers get burned!

A startling metaphor is worth more

than a ring on one’s finger.

But not even Puchmajer’s Rhyming Dictionary

was any use to me.

In vain I snatched for ideas

and fiercely closed my eyes

in order to hear that first magic line.

But in the dark, instead of words,

I saw a woman’s smile and

wind-blown hair.

That has been my destiny.

And I’ve been staggering towards it breathlessly

all my life.

“To Be a Poet” from The Poetry of Jaroslav Seifert

Translated from the Czech by Ewald Osers

Edited by George Gibian

Copyright © 1998 by Ewald Osers and George Gibian

Used by permission of Catbird Press

All rights reserved

Poem selected by the Nobel Library of the Swedish Academy.

Jaroslav Seifert – Facts

Press release

Swedish Academy

The Permanent Secretary

Press release

October 1984

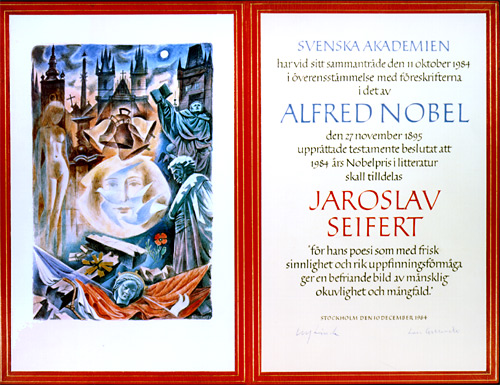

The Nobel Prize in Literature 1984

Jaroslav Seifert

Jaroslav Seifert – a Czechoslovakian poet, 83 years young, can look back upon a career of more than 60 years which shows many signs of being likely to continue. With almost thirty volumes of collected poems behind him, and a few excursions into the realm of prose – above all, his recently published memoirs – he stands out today as the leading poet of his own country. He is read and loved by his countrymen, a national poet who knows how to address both those who have a literary education and those who approach his work without much schooling in their baggage.

Jaroslav Seifert comes from a proletarian background. Born in a working-class district in the outskirts of Prague, he has never lost touch with his popular roots or with the impoverished and socially weak people among whom he grew up. As a young man he believed in the socialistic revolution and wrote poems about it and the promise it held out for the future that enthused many of the other young people of his own generation. His poems were clear, apparently simple and artless, with elements of folk song, familiar speech and scene from everyday life. He rejected the elevated style and formalism of an earlier period. His diction was characterized by lightness of touch, sensuality, melody and rhythm, a lively ingenuity and playfulness alternating with feeling, even pathos. These features of his art have remained constant ever since. He is not, however, a naive artist. He is a poet with an unusually broad stylistic register. At an early stage he came into contact with contemporary European modernism, especially with French poetry, surrealism and dadaism. He is also a sovereign master of traditional forms of poetry with complicated rhythms and rhyme-scheme. He is at much at home with the drastic force of the broadside ballad as with the sophisticated artistry of the sonnet.

The versatility and flexibility of Seifert’s continually inventive and surprising style is matched by an equally rich human register on the level of feeling, insight and imagination. Although a social and political commitment was indeed evident in his very first volume – and has remained a constant feature throughout his oeuvre – he has never become a writer with a party programme. His empathy and his sense of solidarity has focused not upon a system of narrow programme but upon human beings – living, loving, feeling, working, creating, fabulating, suffering, laughing, longing – in short, all those who live, happy or unhappy, a life that is an adventure and an experience, but not one of oppression in accordance to a party programme. Human beings are the ones who create society. The state is there for the people and not vice versa. There is an element of anarchy in Seifert’s philosophy of life – a protest against everything that cuts down life’s possibilities and reduces human beings to cogs in some ideological machine, or yokes them to the harness of some dogma. Perhaps, this sounds innocuous enough to people who themselves have never had to suffer oppression and destitution under political tyranny such as, for example, ourselves here in Sweden. But Seifert has never been innocuous. His poetry, this cornucopia, has also been a political act. Even his juvenile poetry meant a liberation and an adherence to a future that would abolish war, oppression, and would provide joy in life and beauty for those who had hitherto had little thereof. Poetry and art would help to achieve this. His demands and hopes had the confidence and magnificence of youth. During the 1920s these hopes seemed to be on the verge of fulfillment – an avant-garde literature and art accorded with these hopes. But during the 1930s and 1940s the horizon darkened. Economic and political reality proved unable to live up to the rosy dreams. Seifert’s poetry acquired new characteristics – a calmer tone, a remembrance of the history and culture of his own country, a defence of national identity and of those who had preserved it, especially the great authors and artists of the past. Even purely personal experiences and memories were touched with melancholy – the transience of life, the inconstancy of emotion, the impermanence of the childhood and youth which had passed, and of the ties of love. Yet all was not melancholia and nostalgia in Seiferts work – far from it. The concreteness and freshness of his perceptions and his images continued to flourish. He wrote some of his most beautiful love lyrics, his popularity increased, and it was at this time that the foundations of his position as a national poet were firmly laid. He was loved as dearly for the astonishing clarity, musicality and sensuality of his poems as for his unembellished but deeply felt identification with his country and its traditions. He had dissociated himself from the communism of his youth and from the anti-intellectual dogmatism it had developed into. Towards the end of the 1930s and during the 1940s, Czechoslovakia fell under the yoke of the Nazis and Jaroslav Seifert committed himself to the defence of his country, its freedom and its past. He eulogized the Prague rebellion of 1945 and the liberation of his country. At the same time he was active as a journalist, writing in newspapers and periodicals.

The immediate post-war period, however, proved to be one of great disappointment to Seifert and his fellow patriots who had hoped for freedom and a bright future. Poets were expected to engage in political propaganda and satisfy the demands of the powers that be, to whitewash the communist state. Poetry of the kind that Jaroslav Seifert wrote was considered to be disloyal, bourgeois and escapist. It was imperative to “educate the masses”. Seifert was accused of sinking deeper and deeper into subjectivity and pessimism and of having betrayed his class. But he refused to conform to the slogans of social realism. He hibernated – to return in earnest in connection with the thaw of 1956, and, following a long period of illness, has continued to work diligently, first and foremost as a poet, but at times also in political manifestations. He has repudiated the Soviet invasion of Prague and he has signed Charta 77. As has already been observed, he is greatly loved and respected in his own country – and has begun to achieve international recognition as well, in spite of the disadvantage of writing in a language that is relatively little known outside his country. His work is translated, and he is regarded as a poet of current interest in spite of his age.

Today, many people think of Jaroslav Seifert as the very incarnation of the Czechoslovakian poet. He represents freedom, zest and creativity, and is looked upon as this generation’s bearer of the rich culture and literary traditions of his country. He does this partly because of his uncompromising defence of cultural and literary freedom but mainly because of the special quality of his poetry. His method is to depict and praise those things in life and the world that are not governed by dogmas and dictates, political or otherwise. Through words, he paints a world other than the one various authorities and their henchmen threaten to squeeze dry and leave destitute. He praises a Prague that is blossoming and a spring that lives in the memory, in the hopes or the defiant spirit of people who refuse to conform. He praises love, and is indeed one of the truly great love-poets of our time. Tenderness, sadness, sensuality, humour, desire and all the feelings which love between people engenders and encompasses are the themes of these poems. He praises woman – the young maiden, the student, the anonymous, the old, his mother, his beloved. Woman, for him, is virtually a mythical figure, a goddess who represents all that opposes men’s arrogance and hunger for power. Even so, she never becomes an abstract symbol but is alive and present in the poet’s fresh and unconventional verbal art. He conjures up for us another world than that of tyranny and desolation – a world that exists both here and now, although it may be hidden from our view and bound in chains, and one that exists in our dreams and our will, and our art and indomitable spirit. His poetry is a kind of maieutics – an act of deliverance.

Bio-bibliographical notes

Jaroslav Seifert was born in Prague on the 23rd of September 1901. He worked as a journalist until 1950 and since then he has worked as a free-lance writer dedicated to the writing of poetry. Seifert made his début in 1920 and during the 1920s he belonged, in the capacity of one of its founders, to the avant-garde group Devetsil. In his début volume of poems Mesto v slzách (City in Tears) S. finds expression for his proletarian childhood experiences in didactic poems of social life inspired by naivistic art and folk poems and is influenced by Soviet revolutionary art and marxism.

A journey abroad brought S. into contact with French modernism and dadaism. Upon his return S. joined the “poetists” who while remaining political radicals hailed freedom and imagination and art as play, and rejected its socio-moralistic mission. His volume Na vlnách T.S.F. (On the Waves of Télegraphie sans fil) 1925 is considered to be the most typical representative of poetism. A trip to the Soviet Union in 1925 left him even more critical of the revolution and led, in 1929, to a break with the Communist Party. S. joined the Social Democratic Party, an act for which he was later blamed. In the volumes Jablko s klína (The Apple from your Lap) 1933, Ruce Venusiny (The Hands of Venus) 1936, and Jaro, sbohem (Farewell Spring) 1937, S. developed a kind of classical song-lyric of everyday life, which is regarded as the acme of Czechoslovakian poetry.

In the late 1930s with the existence of Czechoslovakia as a state being threatened and during the German occupation, S. developed patriotic themes in his poetry. The poems Osm dní (Eight Days), written in 1937 upon the death of Masamyk, are an address to this founder of Czechoslovakia and were published in six editions the same year. The following volumes of poems: Zhasnete svetla (Turn off the Lights) 1938, Svetlem odená (Robed with Light) 1940, Vejír Bozeny Nemcové (The Fan of Bozena Nemcová) 1940, and Kamenny most (Bridge of Stone) 1944, are resistance poems meant to strengthen national self-confidence. In Prilba hlíny (Helmet with Clay) 1945 he treats among other subjects the Prague rebellion and the liberation of Czechoslovakia.

The communist take-over in 1948 proved a disappointment to S. The volume Písen o Viktorce (The Song of Viktorka) 1950 resulted in accusations of having betrayed his class and led to Seifert’s concentrating upon politically uncontroversial poems in editions that were nonetheless great successes. Among such works belong: Sel malír chude do sveta (A Poor Painter Set out in the World) 1949, Mozart v Praze (Mozart in Prague) 1951, Maminka (about his mother) 1954, Chlapec a hvezdy (The Boy and the Stars) 1956.

A speech given at the Czechoslovakian Writers Association’s Congress in 1956, in which S. criticized the cultural policies of the previous years, and a long illness led to the discontinuation of the publication of new works by S. His Collected Works continued however to be published (vols. 1-5, 1953-57, vols. 6 & 7, 1964 and 1970 respectively). When the climate changed in 1964 S. was awarded the title of National artist. During the next few years he published three new volumes: Koncert na ostrove (Concert on the Island) 1965, Halleyova kometa (Halley’s Comet) 1967, and Ódlévaní zvona (The Casting of Bells, 1983) 1967. These demonstrated a new direction in his work with the abandonment of regular verse forms.

During the Prague Spring in 1968 S. worked for the rehabilitation of persecuted authors. He condemned the Soviet invasion and is one of the people who signed Charta 77. In 1969 he was elected Chairman of the Czechoslovakian Writers’ Association, but was deposed by the Husák regime which however, gradually seems to have accepted his nonconformism. Since 1979 his works has begun to be published again: Destník z Piccadily (An Umbrella from Piccadilly, 1983) was published first in Munich in 1979 and later, the same year, in Prague. Morovy sloup (The Plague Monument, l980, in Swedish Pestmonumentet by Fripress förlag 1982) was published first in Cologne in 1977, and in Prague 1981. Seifert’s memoirs Vsecky krásy sveta (All the Beauty in the World) were published in Cologne and in Prague in 1963.

Sonnets de Prague is available in French (Paris 1974) and English (the English translation in Index on Censorship 1975, nr. 3).

Award ceremony speech

Presentation Speech by Professor Lars Gyllensten, of the Swedish Academy

Translation from the Swedish text

Your Majesties, Your Royal Highnesses, Ladies and Gentlemen,

Jaroslav Seifert can look back upon a career of more than 60 years which shows many signs of being likely to continue. With almost thirty volumes of collected poems behind him he stands out today as the leading poet of his own country. He is read and loved by his countrymen, a national poet who knows how to address both those who have a literary education and those who approach his work without much schooling in their baggage.

Jaroslav Seifert was born in a working-class district on the outskirts of Prague. He has never lost touch with his popular roots or with the impoverished and socially weak people among whom he grew up. As a young man he believed in the socialistic revolution and wrote poems about it and the promise it held out for the future that enthused many of the other young people of his own generation. His poems were clear, apparently simple and artless, with elements of folk song, familiar speech and scenes from everyday life. He rejected the elevated style and formalism of an earlier period. His diction was characterized by lightness of touch, sensuality, melody and rhythm, a lively ingenuity and playfulness alternating with feeling, even pathos. These features of his art have remained constant ever since. He is not, however, a naive artist. He is a poet with an unusually broad stylistic register. At an early stage he came into contact with contemporary European modernism, especially with French surrealism and dadaism. He is also a sovereign master of traditional forms of poetry with complicated rhythms, and rhyme-schemes. He is as much at home with the drastic force of the broadside ballad as with the sophisticated artistry of the sonnet.