President Kim Dae-jung was born on December 3, 1925 in a small village on an island of South Korea’s southwestern coast. He graduated from a commercial high school in 1943 …

Kim Dae-jung – Speed read

Kim Dae-jung was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize for his work for democracy and human rights in South Korea and in East Asia in general, and for peace and reconciliation with North Korea in particular.

Full name: Kim Dae-jung

Born: 3 December 1925, Mokpo, Korea (now South Korea)

Died: 18 August 2009

Date awarded: 13 October 2000

The “sunshine politician”

In 2000, President of South Korea Kim Dae-jung received the Nobel Peace Prize for his “sunshine policy” vis-à-vis North Korea. He wanted to lay a foundation of goodwill and friendship for the peaceful reunification of the two countries, which had been in a state of war since 1950. He also was honoured for his courageous battle for democracy and human rights in his home country, for which he had endured imprisonment, house arrest, abduction and exile. In the summer of 2000, Dae-jung succeeded in arranging a summit with the leader of North Korea. As a result, family members who had been separated since the Korean War (1950-1953) were allowed to meet again. Economic, cultural and humanitarian cooperation agreements were also signed.

“I believe that democracy is the absolute value that makes for human dignity, as well as the only road to sustained economic development and social justice. […] A national economy lacking a democratic foundation is a castle built on sand.”

Kim Dae-jung, Nobel Prize lecture, 10 December 2000.

| Exile To be forced to live outside one’s home country against one’s will. It is also possible to live in exile within one’s own country if one is banished by the authorities to a specific place and forbidden to leave it. |

“Kim Dae-jung’s story has a lot in common with the experience of several other Peace Prize Laureates, especially Nelson Mandela and Andrei Sakharov. And with that of Mahatma Gandhi, who did not receive the prize but would have deserved it.”

Gunnar Berge, Presentation speech, 10 December 2000.

When Jesus saved Kim Dae-jung

Kim Dae-jung was a devout Christian. In his Nobel Prize lecture, he recounted his abduction by South Korean agents in Japan in 1973. They took him to sea and prepared to kill him, but some friends had alerted the US Central Intelligence Agency (CIA), which rescued him at the last minute. Dae-jung described his rescue thus: “Just when they were about to throw me overboard, Jesus Christ appeared before me with such clarity. I clung to him and begged him to save me. At that very moment an airplane came down from the sky to rescue me from the moment of death.”

| CIA Central Intelligence Agency. USA’s intelligence organisation founded in 1947. Responsible for preparing background material for use in the formulation of US foreign policy. Highly influential and often controversial. In 1988 George Bush, Sr. was the first former CIA director to become US president. |

Détente between North and South Korea

The 2000 summit between the two Korean leaders led to better relations between North and South. Thanks to increased trade, South Korea became North Korea’s most important trade partner after China. It sent humanitarian aid north in the form of food, fertiliser and medication, which created trust, as did sports cooperation and further contact between separated families. However, one issue remained worrying: North Korea was unwilling to dismantle its nuclear weapons programme.

“His dream of a united, free and prosperous nation seems less distant today than ever before. But that doesn’t mean that reunification is close at hand – even when promoted by a leader who has been hailed as Asia’s Nelson Mandela.”

Newsweek, 23 October 2001.

Tarnished reputation

In the so-called cash-for-summit scandal which broke in 2003, it was revealed that Kim Dae-jung’s government had transferred at least USD 150 million to North Korea to bring about the summit between the two heads of state in 2000. At the same time, a South Korean intelligence agent disclosed that his country’s president had organised a vigorous campaign to secure the Nobel Peace Prize. One of the Norwegian Nobel Committee members who supported the selection of Kim Dae-jung in 2000, Bishop Gunnar Stålsett, said later that Kim would not have been awarded the Nobel Peace Prize if the committee had known about the bribe and the secret lobbying campaign.

Learn more

Disclaimer: Every effort has been made by the publisher to credit organisations and individuals with regard to the supply of photographs. Please notify the publishers regarding corrections.

Kim Dae-jung – Nobel Symposia

Interpreter’s note

This is a live recording of members of AIIC, the International Association of Conference Interpreters, interpreting simultaneously at the Nobel Centennial Symposia. It is not intended to be a literal or definitive translation of the proceedings.

Kim Dae-jung – Photo gallery

Kim Dae-jung showing his Nobel Prize medal and diploma at the Nobel Peace Prize award ceremony at the Oslo City Hall in Norway, 10 December 2000. To the left: Gunnar Berge, Chairman of the Norwegian Nobel Committee. © Knudsens fotosenter/Dextra Photo, Norsk Teknisk Museum.

Kim Dae-jung receiving his Nobel Prize medal from Gunnar Berge, Chairman of the Norwegian Nobel Committee. © Knudsens fotosenter/Dextra Photo, Norsk Teknisk Museum.

The Nobel Peace Prize Award Ceremony

at the Oslo City Hall, 2000. South Korean President Kim Dae Jung

gives his Nobel Lecture after accepting the 2000 Nobel Peace Prize.

© Pressens Bild AB 2000, SE-112 88 Stockholm, Sweden, telephone: +46 (0)8 738 38 00. Photo: Lise Aserud

Kim Dae-jung and his wife viewing the traditional torch light procession in Oslo from a balcony at the Grand Hotel in Oslo, Norway, 10 December 2000. © Knudsens fotosenter/Dextra Photo, Norsk Teknisk Museum.

Kim Dae-jung signing the guest book during his visit to the Norwegian Nobel Institute, December 2000. © Knudsens fotosenter/Dextra Photo, Norsk Teknisk Museum.

Kim Dae-jung during a press conference at the Norwegian Nobel Institute, December 2000. © Knudsens fotosenter/Dextra Photo, Norsk Teknisk Museum.

Kim Dae-jung during a press conference at the Norwegian Nobel Institute, December 2000. © Knudsens fotosenter/Dextra Photo, Norsk Teknisk Museum.

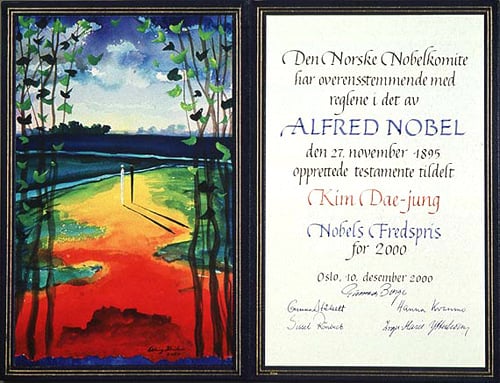

Kim Dae-jung – Nobel diploma

Copyright © The Nobel Foundation 2000

Artist: Elling Reitan

Calligrapher: Inger Magnus

Kim Dae-jung – Nobel Lecture

Kim Dae Jung gives his Nobel Lecture.

© Pressens Bild AB 2000, SE-112 88 Stockholm, Sweden, telephone: +46 (0)8 738 38 00. Photo: Lise Aserud

Nobel Lecture, Oslo, December 10, 2000

Your Majesty, Your Royal Highnesses, Members of the Norwegian Nobel Committee, Excellencies, Ladies and Gentlemen,

Human rights and peace have a sacred ground in Norway. The Nobel Peace Prize is a solemn message that inspires all humanity to dedicate ourselves to peace. I am infinitely grateful to be given the honor. But I think of the countless people and colleagues in Korea, who have given themselves willingly to democracy and human rights and the dream of national unification. And I must conclude that the honor should go to them.

I also think of the many countries and friends around the world, who have given generous support to the efforts of my people to achieve democratization and inter-Korean reconciliation. I thank them very sincerely.

I know that the first South-North Korean summit meeting in June and the start of inter-Korean reconciliation is one of the reasons for which I am given the Nobel Peace Prize.

Distinguished guests,

I would like to speak to you about the breakthrough in South-North Korean relations that the Nobel Committee has judged worthy of its commendation. In mid-June, I traveled to Pyongyang for the historic meeting with Chairman Kim Jong-il of the North Korean National Defense Commission. I went with a heavy heart not knowing what to expect, but convinced that I must go for the reconciliation of my people and peace on the Korean peninsula. There was no guarantee that the summit meeting would go well. Divided for half-a-century after a three-year war, South and North Korea have lived in mutual distrust and enmity across the barbed-wire fence of the demilitarized zone.

To replace the dangerous stand-off with peace and cooperation, I proclaimed my sunshine policy upon becoming President in February 1998, and have consistently promoted its message of reconciliation with the North: first, we will never accept unification through communization; second, nor would we attempt to achieve unification by absorbing the North; and third, South and North Korea should seek peaceful coexistence and cooperation. Unification, I believe, can wait until such a time when both sides feel comfortable enough in becoming one again, no matter how long it takes. At first, North Korea resisted, suspecting that the sunshine policy was a deceitful plot to bring it down. But our genuine intent and consistency, together with the broad support for the sunshine policy from around the world, including its moral leaders such as Norway, convinced North Korea that it should respond in kind. Thus, the South-North summit could be held.

I had expected the talks with the North Korean leader to be extremely tough, and they were. However, starting from the shared desire to promote the safety, reconciliation and cooperation of our people, the Chairman and I were able to obtain some important agreements.

First, we agreed that unification must be achieved independently and peacefully, that unification should not be hurried along and for now the two sides should work together to expand peaceful exchanges and cooperation and build peaceful coexistence.

Second, we succeeded in bridging the unification formulas of the two sides, which had remained widely divergent. By proposing a “loose form of federation” this time, North Korea has come closer to our call for a confederation of “one people, two systems, two independent governments” as the pre-unification stage. For the first time in the half-century division, the two sides have found a point of convergence on which the process toward unification can be drawn out.

Third, the two sides concurred that the US military presence on the Korean peninsula should continue for stability on the peninsula and Northeast Asia.

During the past 50 years, North Korea had made the withdrawal of the US troops from the Korean peninsula its primary point of contention. I said to Chairman Kim: “The Korean peninsula is surrounded by the four powers of the United States, Japan, China and Russia. Given the unique geopolitical location not to be found in any other time or place, the continued US military presence on the Korean peninsula is indispensable to our security and peace, not just for now but even after unification. Look at Europe. NATO had been created and American troops stationed in Europe so as to deter the Soviet Union and the East European bloc. But, now, after the fall of the communist bloc, NATO and US troops are still there in Europe, because they continue to be needed for peace and stability in Europe.”

To this explanation of mine, Chairman Kim, to my surprise, had a very positive response. It was a bold switch from North Korea’s long-standing demand, and a very significant move for peace on the Korean peninsula and Northeast Asia.

We also agreed that the humanitarian issue of the separated families should be promptly addressed. Thus, since the summit, the two sides have been taking steps to alleviate their pain. The Chairman and I also agreed to promote economic cooperation. Thus, the two sides have signed an agreement to work out four key legal instruments that would facilitate the expansion of inter-Korean economic cooperation, such as investment protection and double-taxation avoidance agreements. Meanwhile, we have continued with the humanitarian assistance to the North, with 300,000 tons of fertilizer and 500,000 tons of food. Sports, culture and arts, and tourism exchanges have also been activated in the follow-up to the summit.

Furthermore, for tension reduction and the establishment of durable peace, the defense ministers of the two sides have met, pledging never to wage another war against each other. They also agreed to the needed military cooperation in the work to relink the severed railway and road between South and North Korea.

Convinced that improved inter-Korean relations is not enough for peace to fully settle on the Korean peninsula, I have strongly encouraged Chairman Kim to build better ties with the United States and Japan as well as other western countries. After returning from Pyongyang, I urged President Clinton of the United States and Prime Minister Mori of Japan to improve relations with North Korea.

At the 3rd ASEM Leaders’ Meeting in Seoul in late October, I advised our friends in Europe to do the same. Indeed, many advances have recently been made between North Korea and the United States, as well as between North Korea and many countries of Europe. I am confident that these developments will have a decisive influence in the advancement of peace on the Korean peninsula.

Ladies and gentlemen,

In the decades of my struggle for democracy, I was constantly faced with the refutation that western-style democracy was not suitable for Asia, that Asia lacked the roots. This is far from true. In Asia, long before the west, the respect for human dignity was written into systems of thought, and intellectual traditions upholding the concept of “demos” took root. “The people are heaven. The will of the people is the will of heaven. Revere the people, as you would heaven.” This was the central tenet in the political thoughts of China and Korea as early as three thousand years ago. Five centuries later in India, Buddhism rose to preach the supreme importance of one’s dignity and rights as a human being.

There were also ruling ideologies and institutions that placed the people first. Mencius, disciple of Confucius, said: “The king is son of heaven. Heaven sent him to serve the people with just rule. If he fails and oppresses the people, the people have the right, on behalf of heaven, to dispose of him.” And this, 2,000 years before John Locke expounded the theory of the social contract and civic sovereignty.

In China and Korea, feudalism was brought down and replaced with counties and prefectures before the birth of Christ, and civil service exams to recruit government officials are a thousand years-old. The exercise of power by the king and high officials were monitored by robust systems of auditing. In sum, Asia was rich in the intellectual and institutional traditions that would provide fertile grounds for democracy. What Asia did not have was the organizations of representative democracy. The genius of the west was to create the organizations, a remarkable accomplishment that has greatly advanced the history of humankind.

Brought into Asian countries with deep roots in the respect for demos, western democratic institutions have adapted and functioned admirably, as can be seen in the cases of Korea, Japan, the Philippines, Indonesia, Thailand, India, Bangladesh, Nepal, and Sri Lanka. In East Timor, the people went to the polling stations to vote for their independence, despite the threat to their lives from the savage militias. In Myanmar, Madam Aung San Suu Kyi is still leading the struggle for democracy. She retains wide support of the people. I have every confidence that there, too, democracy will prevail and a representative government will be restored.

Distinguished guests,

I believe that democracy is the absolute value that makes for human dignity, as well as the only road to sustained economic development and social justice.

Without democracy the market economy cannot blossom, and without market economics, economic competitiveness and growth cannot be achieved.

A national economy lacking a democratic foundation is a castle built on sand. Therefore, as President of the Republic of Korea, I have made the parallel development of democracy and market economics, supplemented with a system of productive welfare, the basic mission of my government.

To achieve the mission, during the past two-and-a-half years, we have taken steps to actively guarantee the democratic rights of our citizens. We have also been steadfast in implementing bold reforms in the financial, corporate, public and labor sectors. Furthermore, the efforts to promote productive welfare, focusing on human resources development for all citizens, including the low-income classes, have made much headway.

The reforms will continue in Korea. We are committed to the early completion of the current reform measures, as well as to reform as an on-going process of transformation into a first-rate economy of the 21st century. This we hope to achieve by combining the strength of our traditional industries with the endless possibilities that lie in the information and bio-tech fields.

The knowledge and information age of the 21st century promises to be an age of enormous wealth. But it also presents the danger of hugely growing wealth gaps between and within countries. The problem presents itself as a serious threat to human rights and peace. In the new century, we must continue the fight against the forces that suppress democracy and resort to violence. We must also strive to deal with the new challenge to human rights and peace with steps to alleviate the information gap, to help the developing countries and the marginalized sectors of society to catch up with the new age.

Your Majesty, Your Royal Highnesses, ladies and gentlemen,

Allow me to say a few words on a personal note. Five times I faced near death at the hands of dictators, six years I spent in prison, and forty years I lived under house arrest or in exile and under constant surveillance. I could not have endured the hardship without the support of my people and the encouragement of fellow democrats around the world. The strength also came from deep personal beliefs.

I have lived, and continue to live, in the belief that God is always with me. I know this from experience. In August of 1973, while exiled in Japan, I was kidnapped from my hotel room in Tokyo by intelligence agents of the then military government of South Korea. The news of the incident startled the world. The agents took me to their boat at anchor along the seashore. They tied me up, blinded me, and stuffed my mouth. Just when they were about to throw me overboard, Jesus Christ appeared before me with such clarity. I clung to him and begged him to save me. At that very moment, an airplane came down from the sky to rescue me from the moment of death.

Another faith is my belief in the justice of history. In 1980, I was sentenced to death by the military regime. For six months in prison, I awaited the execution day. Often, I shuddered with fear of death. But I would find calm in the fact of history that justice ultimately prevails. I was then, and am still, an avid reader of history. And I knew that in all ages, in all places, he who lives a righteous life dedicated to his people and humanity may not be victorious, may meet a gruesome end in his lifetime, but will be triumphant and honored in history; he who wins by injustice may dominate the present day, but history will always judge him to be a shameful loser. There can be no exception.

Your Majesty, Your Royal Highnesses, ladies and gentlemen,

Accepting the Nobel Peace Prize, the honoree is committed to an endless duty. I humbly pledge before you that, as the great heroes of history have taught us, as Alfred Nobel would expect of us, I shall give the rest of my life to human rights and peace in my country and the world, and to the reconciliation and cooperation of my people. I ask for your encouragement and the abiding support of all who are committed to advancing democracy and peace around the world.

Thank you.

Kim Dae-jung – Other resources

Links to other sites

Kim Dae-jung Presidential Library and Museum

Press release

The Norwegian Nobel Committee has decided to award the Nobel Peace Prize for 2000 to Kim Dae-jung for his work for democracy and human rights in South Korea and in East Asia in general, and for peace and reconciliation with North Korea in particular.

In the course of South Korea’s decades of authoritarian rule, despite repeated threats on his life and long periods in exile, Kim Dae-jung gradually emerged as his country’s leading spokesman for democracy. His election in 1997 as the republic’s president marked South Korea’s definitive entry among the world’s democracies. As president, Kim Dae-jung has sought to consolidate democratic government and to promote internal reconciliation within South Korea.

With great moral strength, Kim Dae-jung has stood out in East Asia as a leading defender of universal human rights against attempts to limit the relevance of those rights in Asia. His commitment in favour of democracy in Burma and against repression in East Timor has been considerable.

Through his “sunshine policy”, Kim Dae-jung has attempted to overcome more than fifty years of war and hostility between North and South Korea. His visit to North Korea gave impetus to a process which has reduced tension between the two countries. There may now be hope that the cold war will also come to an end in Korea. Kim Dae-jung has worked for South Korea’s reconciliation with other neighbouring countries, especially Japan.

The Norwegian Nobel Committee wishes to express its recognition of the contributions made by North Korea’s and other countries’ leaders to advance reconciliation and possible reunification on the Korean peninsula.

Oslo, 13 October 2000

Kim Dae-jung – Facts

Award ceremony speech

Presentation Speech by Gunnar Berge, Chairman of the Norwegian Nobel Committee, Oslo, December 10, 2000.

Translation of the Norwegian text.

Your Majesty, Your Royal Highnesses, Excellencies, Ladies and Gentlemen,

The Norwegian Nobel Committee has decided to award the Nobel Peace Prize for the year 2000 to Kim Dae-jung. He receives the prize for his lifelong work for democracy and human rights in South Korea and East Asia in general, and for peace and reconciliation with North Korea in particular. We welcome the Laureate here today.

The question has been raised of whether it is too early to award the prize for a process of reconciliation which has only just begun. It would suffice to say in reply that Kim Dae-jung’s work for human rights made him a worthy candidate irrespective of the recent developments in relations between the two Korean states. It is also clear, however, that his strong commitment to reconciliation with North Korea, and the results that have been achieved – especially in the past year – added a new and important dimension to Kim Dae-jung’s candidacy.

While recognising that reverses in international peace work are something one has to be prepared for, the Nobel Committee nevertheless adheres to the principle: nothing ventured, nothing gained. The Peace Prize is a reward for the steps that have been taken so far. However, as so often before in the history of the Nobel Peace Prize, it is intended this year, too, as an encouragement to advance still further along the long road to peace and reconciliation.

This is to a large extent a matter of courage: Kim Dae-jung has had the will to break with fifty years of ingrained hostility, and to reach out a cooperative hand across what has probably been the world’s most heavily guarded frontier. His has been the kind of personal and political courage which, regrettably, is all too often missing in other conflict-ridden regions. The same applies to peace work as to life in general when you set out to cross the highest mountains: the first steps are the hardest. But you can count on plenty of company along the glamorous finishing stretch. Gunnar Roaldkvam, a writer from Stavanger, puts this so simply and so aptly in his poem “The last drop”:

Once upon a time

there were two drops of water;

one was the first,

the other the last.The first drop

was the bravest.I could quite fancy

being the last drop,

the one that makes everything

run over,

so that we get

our freedom back.But who wants to be

the first

drop?

Today, Kim Dae-jung is the president of a democratic South Korea. His path to power has been long – extremely long. For decades he fought a seemingly hopeless fight against an authoritarian regime. One may well ask where he found the strength. His own answer is: “I used all my strength to resist the dictatorial regimes, because there was no other way to defend the people and promote democracy. I felt like a homeowner whose house was invaded by a robber. I had to fight the intruder with my bare hands to protect my family and property without thinking of my own safety.”

In the 1950s, when Kim ran for election to the national assembly, the police were used to prevent support for any other candidates than the regime’s own. He was not elected until 1961, but that success was short-lived: a military coup three days later led to the dissolution of the assembly. But Kim did not give up. In 1963, after ten years of almost continuous political struggle, he finally took a seat in the national assembly as an opposition representative. The ruling party, it should be added, tried to buy him. Kim was not for sale.

In 1971, Kim Dae-jung ran in the presidential election, winning 46 per cent of the votes despite considerable ballot-rigging. This made him a serious threat to the military regime. As a result, he spent many long years, first in prison, then in house arrest and in exile in Japan and the United States. He also underwent kidnapping and assassination attempts. Somehow enduring all these trials, Kim kept up his outspoken opposition to the regime.

As a member of a delegation from the Norwegian Storting, I visited South Korea in 1979, a visit which among other things brought me into contact with supporters of Kim Dae-jung. I am glad I was able then to serve as a link to important connections in Scandinavia.

Even under severe prison conditions, Kim Dae-jung managed to find things to live for. With indomitable optimism, he wrote about the pleasures he found in prison. Reading all kinds of eastern and western books: theology, politics, economics, history and literature. The brief meetings with his family. The letters from those closest to him, and the opportunities to write back, despite all the attempts to prevent him. And finally the flowers in the tiny patch of a garden where he was allowed to spend an hour a day.

Kim Dae-jung’s story has a lot in common with the experience of several other Peace Prize Laureates, especially Nelson Mandela and Andrei Sakharov. And with that of Mahatma Gandhi, who did not receive the prize but would have deserved it. To outsiders, Kim’s invincible spirit may appear almost superhuman. On this point, too , the Laureate takes a more sober view: “Many people tell me,” he says, “that I am courageous, because I have been to prison six or seven times and overcome several close calls in my life. However, the truth is that I am as timid now as I was in my boyhood. Considering what I have experienced in my life, I should not be afraid of being imprisoned. But, whenever I was locked up, I was invariably fearful and anxious.” Self-knowledge of this order does not detract from the courage!

Kim Dae-jung ran in two more presidential elections, in 1987 and 1992. If no military regime stood in his way, the argument was used against him, in a country of sharp regional divisions, that he came from the wrong region. Finally wearying of the struggle, he withdrew from active politics after the 1992 election.

But in 1997 Kim Dae-jung saw a new opportunity. Incredibly enough, with his political enemies divided amongst themselves, the military regime’s leading opponent was elected president. That was the definitive proof that South Korea had at long last found a place among the world’s democracies.

The idea of revenge must have occurred to the new president. Instead, as with Nelson Mandela, forgiveness and reconciliation became the main planks in Kim’s political platform and guided the steps he took. Kim Dae-jung forgave most things – including the unforgivable.

What had taken place was a democratic revolution. But even after a revolution, some features of the old order live on. In a democratic perspective, South Korea still has some way to go where reform of the legal system and of security legislation is concerned. According to Amnesty International, there are still long-term political prisoners in South Korean gaols. Others maintain that the rights of organized labour are not sufficiently safeguarded. Our reply is that we feel confident that Kim Dae-jung will complete the process of democratisation of which he has been the foremost spokesman for almost half a century.

An important debate is currently being conducted in Asia concerning the status of human rights. It is argued by some that such rights are a western invention, a tool for achieving western political and cultural dominance. Kim rejects this view, just as he also denies that there are any special Asian, as distinct from universal, human rights. The same way of thinking led the Nobel Committee, in its grounds for this year’s award, to draw particular attention to the important part Kim has played in the development of human rights throughout East Asia. As José Ramos Horta, Peace Prize Laureate in 1996 and with us here today, has stated, Kim also vigorously took up the cause of East Timor. There was great symbolic force in the decision to place the South Korean army, used only a few years previously to suppress political opposition in its own country, at the disposal of the global community in defence of human rights in East Timor.

Kim Dae-jung has also actively supported Aung San Suu Kyi, Peace Prize Laureate in 1991, in her heroic struggle against the dictatorship in Burma . Our thoughts today also reach out to her, prevented as she has so far been from coming to Norway to receive the Peace Prize she so richly deserves. Unfortunately the regime is once again stepping up its pressure on Aung San Suu Kyi.

Kim was elected president on a program of extensive reforms in South Korea, and an active policy of cooperation with North Korea now widely spoken of as the “sunshine policy”. The term originated in Aesop’s fable about the traveller who in a strong north wind drew his cloak ever more closely about him, only to have to take it off in the end because of the warmth of the sun.

The sunshine policy is designed, if not to stop the wind, then at least to lessen the cold through gradually increasing interaction and an emphasis on the common interests of the two states. Kim Dae-jung has made it clear that South Korea has no intention of annexing or absorbing its northern neighbour. The target is reunification, although both parties know that it will take time and will require the most thorough preparation.

There can be little doubt that to date Kim Dae-jung has been the prime mover behind the ongoing process of détente and reconciliation. Perhaps his role can best be compared with Willy Brandt‘s, whose Ostpolitik was of such fundamental importance in the normalisation between the two German states, and won him the Peace Prize. Brandt’s Ostpolitik alone could not have led to German unification, but it was a prerequisite for the union which followed in 1989-90. From South Korea’s point of view, the political side of Germany’s unification looks attractive, while the economic side, with a price tag that may be much higher in Korea than in Germany, is a warning to make haste slowly.

The dialogue between Kim Dae-jung and Kim Jung II at the Pyongyang summit last June led to more than loose declarations and airy rhetoric. The pictures of family members meeting after five decades of separation made a deep impression all over the world. However restricted and controlled these contacts may be, the tears of joy are a stark contrast to the cold, hatred and discouragement felt so strongly by all visitors to the border at Panmunjon.

The people of North Korea have lived under extremely difficult conditions for a long time. The international community can not be indifferent to their hunger, or remain silent in the face of the country’s massive political repression. On the other hand, North Korea’s leaders deserve recognition for their part in the first steps towards reconciliation between the two countries.

In most of the world, the cold war ice age is over. The world may see the sunshine policy thawing the last remnants of the cold war on the Korean peninsula. It may take time. But the process has begun, and no one has contributed more than today’s Laureate, Kim Dae-jung. In the poet’s words, “The first drop was the bravest.”