Otto Wallach – Nobel Lecture

Nobel Lecture, December 12, 1910

Alicyclic Compounds

Read the Nobel Lecture

Pdf 80 kB

Otto Wallach – Nominations

Award ceremony speech

Presentation Speech by the Rector General of National Antiquities, Professor O. Montelius, President of the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences, on December 10, 1910

Your Majesty, Your Royal Highnesses, Ladies and Gentlemen.

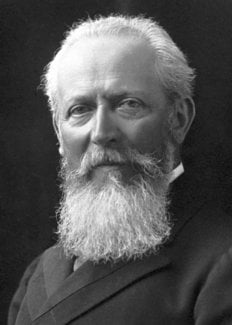

At the meeting of 12th November, the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences decided to award this year’s Nobel Prize for Chemistry to Geheimrat Otto Wallach, Professor at Göttingen University, for the services which he has rendered in the development of organic chemistry and the chemical industry by his pioneering work in the field of alicyclic compounds.

As is well known, plants contain more or less strongly smelling components, which play an important part in their vital functions and particularly in their fecundation. These components, from ancient times, were always combined under the name of “essential oils” on account of their volatility. Very early, certain peculiar hydrocarbons had been isolated from these essential oils, which were called terpenes, because the ordinary turpentine oil is constituted of a mixture of these. These hydrocarbons occupied a special position in comparison to others in the chemical aspect. They all had the same composition by percentage and most of them even had the same molecular weight, they reached boiling-point at approximately the same temperature; they showed, however, certain differences in smell, in optical properties and in chemical reactions, so that they could not be identified with each other. In the course of time nearly one hundred of these terpenes have been described in the chemical literature and they were usually named after the plants from which they were isolated. On account of their instability they were particularly difficult to handle and chemical theory could not accommodate anywhere near such a great number of isomers; a thorough study of this field therefore seemed practically hopeless.

Under such circumstances, the fact that this previously so mysterious field is now presented to us clearly in experimental as well as in theoretical respects, must be regarded as one of the greatest triumphs which chemical science has celebrated in the last few years. The honour for this is due, primarily, to Otto Wallach, who not only pioneered this work from the start, but also continued to a certain degree to lead in its continuation.

Wallach started working in this field as early as 1884. After six years he submitted the results obtained up to that time in form of a compilation. He had succeeded in finding methods of sharply and distinctly characterizing the various terpenes, so that these could be recognized in mixtures and also separated from each other in these. By means of these methods he had also been able to reduce the number of the so-far known terpenes to a surprisingly low figure – i.e. 8 – to which later a few newly discovered ones were added. He had further proved that terpene compounds very easily undergo changes when in contact with even the most ordinary reagents and are transformed into each other, which makes investigations in the field of terpene chemistry especially difficult and delicate. By investigating as many compounds as possible, he succeeded in determining in principle those conditions which excluded isomerization; he also developed the general technique for these investigations.

Through this pioneering work Wallach opened up a new field for research, which could be investigated further with good hope of success. And it is true that this field was immediately tackled by a great number of research scientists in various countries. Organic chemistry, during the decade that followed, was characterized by the study of the so-called alicyclic compounds, among which the terpenes and the closely related types of camphor with their derivatives played the most important part. Wallach himself, by overcoming considerable difficulties with admirable success and though perseverance, made continuous progress in the field opened up by himself. An extraordinarily large number of compounds were prepared by him and he also determined their structure. Apart from the terpenes proper, he also investigated and scientifically characterized various previously known or newly discovered natural products, such as alcohols, ketones, sesquiterpenes and polyterpenes belonging to the terpene series, which in part are also of great significance in biological and technical respects. For this reason the alicyclic series has, since the middle of the eighties, assumed such size and importance as to make it the equal of the other three main series within organic chemistry. Wallach contributed more towards this than any other research scientist.

Wallach’s research activity did not only decisively influence theoretic chemistry, but also chemical industry, namely that branch of the industry which processes essential oils. According to recently published statistics, annual production of such preparations in Germany alone has risen from 12 million Mark in 1885 to 45-50 million Mark. Wallach’s scientific work contributed to this directly as well as indirectly-directly by making the terpenes and their derivatives known and analytically determinable, whereby technology was provided with new methods of manufacturing and the previously often occurring adulterations of the raw materials were prevented; and indirectly by the fact that a large number of his students entered industry and there applied his working methods and his exact way of research. Wallach himself has never patented his discoveries, but always put his observations at the disposal of industry free of charge.

The Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences wished to pay tribute to this work – which had from the start been carefully planned, executed with great skill and terrific energy, had in the course of time become ever more profound and more comprehensive, by which science has conquered new fields, and pioneering work has been done towards industrial development by awarding the Nobel Prize in Chemistry for the year 1910 to Professor Otto Wallach.

Professor Wallach. The Royal Academy of Sciences has awarded to you this year’s Nobel Prize for Chemistry in recognition of the momentous services you rendered in the development of organic chemistry and the chemical industry by your pioneering work in the field of alicyclic compounds.

Once again it has been proved that results obtained by scientific research, which at first seem to be solely of theoretical interest may actually be of great practical importance.

Because you have introduced us to a significant field in organic chemistry which previously was practically unknown, you will now receive the Nobel Prize, the highest award which our Academy can bestow.

Speed read: Essential chemical plants

From apples to ylang-ylang, the range of scents and flavours that fill Nature’s vast garden of plants are formed chiefly from specific combinations of volatile organic compounds, known collectively as essential oils. For decades the tools used in chemistry were deemed ill-equipped to untangle these complex and unstable mixtures, until Otto Wallach devised ways in which to reveal the essential virtues of plants.

Through a carefully controlled series of reactions with common laboratory reagents (such as hydrogen chloride and hydrogen bromide), Wallach successfully characterised the key components from a wide range of essential oils and deduced their structures. In contrast to the widely held notion that the active components of essential oils from different plant species must be chemically different from one another, Wallach found that many of these substances are remarkably similar, belonging to a class of compounds that he called terpenes. These compounds are constructed from stitching various numbers of a basic chemical unit together; the unit in question sharing its structure with the compound isoprene, which is used in the production of synthetic rubber.

The ease with which different terpenes can transform into each other made them especially tricky and fragile to study, but Wallach’s methods for isolating pure essential oils from natural plant mixtures opened up a new field of research in organic chemistry. Chemists could now characterise increasing numbers of terpenes and closely related chemicals, which are all members of a group known as alicyclic compounds. Wallach’s pioneering work also had a tremendous impact on the chemical industry. Traditionally crude extracts of plant essential oils were used to create a wide assortment of medicines and perfumes. Armed with Wallach’s methods, chemists could begin to isolate active plant essential oils of medicinal or chemical interest, allowing them to manufacture synthetic, cheaper versions.

The Nobel Prize in Chemistry 1910

Otto Wallach – Biographical

Otto Wallach was born on March 27, 1847, in Königsberg, Germany, the son of Gerhard Wallach and his wife, née Otillie Thoma. His father was a high-ranking civil servant, who later became Auditor General at Potsdam.

During his early school years at the humanistic “Gymnasium” at Potsdam, Wallach had a profound liking for history and art – in those days subjects like chemistry were hardly taught at secondary-school level.

In 1867 he went to Göttingen to study chemistry with Wöhler, Fittig and Hübner but soon left for Berlin to study for one semester under A.W. Hofmann and G. Magnus. After his return to Göttingen he worked so hard that he managed to obtain his doctor’s degree – in 1869 under Hübner – after studying for only five semesters. (At that time working hours at the Wöhler laboratory were from 7 a.m. till 5 p.m., after which gas was turned off and some work had to be rounded-off under the light of privately bought candles.) His thesis dealt with the position isomers in the toluene series.

In 1869 and 1870 he was assistant to H. Wichelhaus in Berlin, with whom he worked on the nitration of b-naphthol. Easter 1870 found him in Bonn with Kekulé. The latter, himself an artist at heart and who once seriously considered making architecture his profession, had written to Wallach: “It will not hurt you to come to Bonn. Here we are leading a scientific artist life.” That same year, however, Wallach had to leave Bonn for military service in the Franco-Prussian war.

After the war he tried for the third time to establish himself in Berlin, working with a newly founded firm “Aktien-Gesellschaft für Anilin-Fabrikation” (later “Agfa”), but his fragile health could not stand the noxious fumes of the factory, and in 1872 he returned to Bonn, where he stayed for 19 years. He first became assistant in the organic laboratory, and later was appointed Privatdozent. In 1876 came his appointment as Professor Extraordinary. When in 1879 the Chair of Pharmacology became vacant he was obliged to occupy it, which forced him to specialize in this direction. It was during this period that he discovered the iminochlorides by the action of phosphorus pentachloride on the acid amides. But when Kekulé drew his attention to the existence of an old forgotten cupboard full of bottles containing essential oils, and invited him to make a study of the contents, he became absorbed in the matter, thus entering a field of study in which he was to be the eminent pioneer for more than a decade, and which was to be his main life-work, crowned with the highest possible distinction.

Already in his first publication (1884) he raised the question of the diversity of the various members of the C10H16 group, which in current practice at that time came under a multitude of names ranging from terpene to camphene, citrene, carvene, cinene, cajuputene, eucalyptine, hesperidine, etc. Utilizing common reagents such as hydrogen chloride and hydrogen bromide, he succeeded in characterizing the differences between the structure of these compounds. A year later he could establish that many of them were indeed identical. In 1909 he published the results of his extensive studies in his book Terpene und Campher, a volume of 600 pages dedicated to his pupils.

Mention should also be made of his other investigations; the conversion of chloral into dichloroacetic acid, the series of studies on the amide chlorides, imide chlorides, amidines, glyoxalines, etc., his work on azo dyes and diazo compounds, and many others. They all denote his practical skill: like Emil Fischer and Adolf von Baeyer, he relied more on carefully performed experiments than on theoretical deliberations.

In 1889 he was appointed Victor Meyer’s successor in Wöhler’s Chair, which made him at the same time Director of the Chemical Institute at Göttingen. He retired in 1915 from these posts when at the start of World War I six of his assistants were killed in action.

Wallach received the Nobel Prize in 1910 for his work on alicyclic compounds. His other honours included Honorary Fellowships of the Chemical Society (1908), Honorary Doctorates of the Universities of Manchester, Leipzig and the Technological Institute of Braunschweig. In 1912 he became Honorary Member of the Verein Deutscher Chemiker. He received the Kaiserlicher Adlerorden III. Klasse (Imperial Order of the Eagle) in 1911, the Davy Medal in Gold and Silver in 1912, and in 1915 the Königlicher Kronorden II. Klasse (Royal Order of the Crown).

Wallach remained a bachelor throughout his life, and died on February 26, 1931.

This autobiography/biography was written at the time of the award and first published in the book series Les Prix Nobel. It was later edited and republished in Nobel Lectures. To cite this document, always state the source as shown above.

The Nobel Foundation's copyright has expired.