IRÈNE JOLIOT-CURIE

Nobel Prize in Chemistry 1935

The radiochemist Irène Joliot-Curie was a battlefield radiologist, activist, politician, and daughter of two of the most famous scientists in the world: Marie and Pierre Curie. Along with her husband, Frédéric, she discovered the first-ever artificially created radioactive atoms, paving the way for innumerable medical advances, especially in the fight against cancer.

Photograph showing a group of alpha-rays from polonium from Irène Joliot-Curie and Frédéric Joliot.

Photo: Iréne Joliot-Curie and Frédéric Joliot. Enquiries to Science Museum, London

Photograph showing a pair of electrons produced in a lead screen by gamma-rays of beryllium bombarded by alpha-rays from polonium, together with a proton projected by a neutron (from Irène Joliot-Curie and Frédéric Joliot).

Photo: Iréne Joliot-Curie and Frédéric Joliot. Enquiries to Science Museum, London

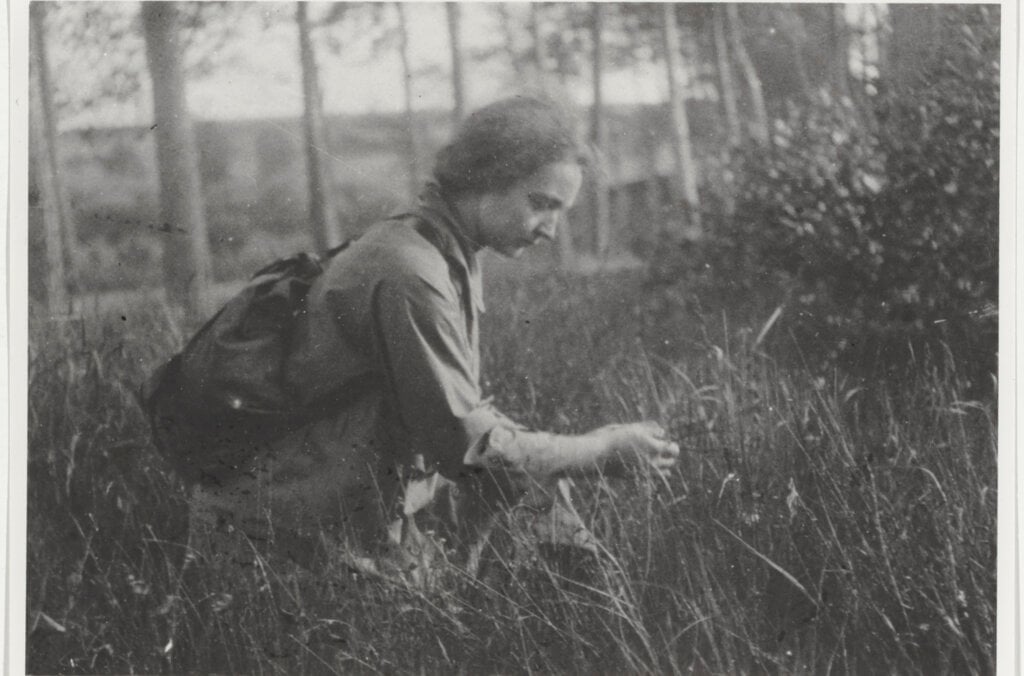

Irène Joliot-Curie was born in Paris in 1897, six years before her parents were awarded the Nobel Prize in Physics. Early on, they were largely absent, working long hours to isolate radioactive elements. So the young Joliot-Curie was raised by her paternal grandfather, Eugene, a retired doctor who taught her to love nature, poetry, and radical politics.

Her education was sometimes unusual. When she was a young teenager, Joliot-Curie attended a cooperative “school” organised by her mother, in which six professors taught each other’s children in their subjects of expertise, from physics and mathematics to German and art.

Fame struck the Curie family in 1903, followed soon after by tragedy. In 1906, when she was eight years old, Pierre Curie was killed in an accident. Marie Curie began then to spend more time with her daughters (Eve, Irène’s sister, had been born just 16 months before Pierre’s death), and over the years Joliot-Curie took the place of her father as a supporter and a colleague of her mother’s.

During World War I Joliot-Curie learned first-hand that science could save lives. She soon found herself assisting her mother, whose mission was to bring the power of the X-ray to help field surgeons find shrapnel in wounded soldiers.

Marie Curie and Irène Joliot-Curie at the Radium Institute, 1922.

Photo: © Association Curie Joliot-Curie

Irène Joliot-Curie at the Radium Institute, 1923.

Photo: © Association Curie Joliot-Curie

Irène Curie and her mother Marie Curie at the Hoogstade Hospital in Belgium, 1915. Radiographic equipment is installed.

© Association Curie Joliot-Curie. Photographer unknown

At age 18, Joliot-Curie was running radiology units in mobile field hospitals, teaching nurses to run X-ray machines, and operating them herself on the Belgian front.

Irène Joliot-Curie climbing down from a “radiological car”, 1916.

Photo: © Association Curie Joliot-Curie

Irène Curie, nurse for the Red Cross, in front of her tent at Hoogstade in Belgium, 1915.

Photo: © Association Curie Joliot-Curie

After the war, while working toward her doctorate, Joliot-Curie became her mother’s assistant at the Radium Institute, where her mother asked her to train fellow researcher, Frédéric Joliot. As she taught this chemical engineer about the various methods of their radiochemical lab, she found in Joliot a partner in work who could also be a partner in life. The two young scientists married in 1926, and by 1928 were signing all their research jointly.

Irène Joliot-Curie in the chemistry room of the Curie Laboratory, Radium Institute, March 1922.

Photo: © Association Curie Joliot-Curie

Irène Joliot-Curie and Frédéric Joliot at work in their laboratory, 1938.

Photo: © Association Curie Joliot-Curie

From left to right: Marie Curie, Irène Joliot-Curie, the Curie-Joliot children, Frédéric Joliot, and Madame Joliot.

Photo: Société Française de Physique, Paris

In the early 1930s, the Joliot-Curies twice came close to making significant discoveries, but misinterpreted the results of their experiments – experiments that identified both the positron and the neutron, if only they had realised it.

“Without the love of research, mere knowledge and intelligence cannot make a scientist.”

Irène Joliot-Curie

At last, in 1934, they made the discovery that would alter the course of radiation research and secure their place in the history of science. After bombarding aluminium foil with alpha-particles (helium nuclei), they noticed that the aluminium continued to emit positrons even after the bombardment of alpha-particles had stopped. They deduced that alpha-particle bombardment had converted stable aluminium atoms into radioactive atoms. In other words, they had manufactured radioactive atoms.

Irène Curie at a radiology unit in Amiens, 1916.

Photo: © Association Curie Joliot-Curie

Irène Joliot-Curie and Frédéric Joliot in 1934

Photo: Société Française de Physique

The ability to artificially create radioactive atoms changed the course of modern physics.

Before, the only way for scientists to obtain radioactive elements was to extract them from their natural ores, an extremely difficult and costly process. Now that they could be made in a laboratory, there was an explosion of research into radioisotopes and the practical applications of radiochemistry, especially in medicine.

Radioisotopes quickly became – and remain – invaluable tools in biomedical research and in cancer treatment.

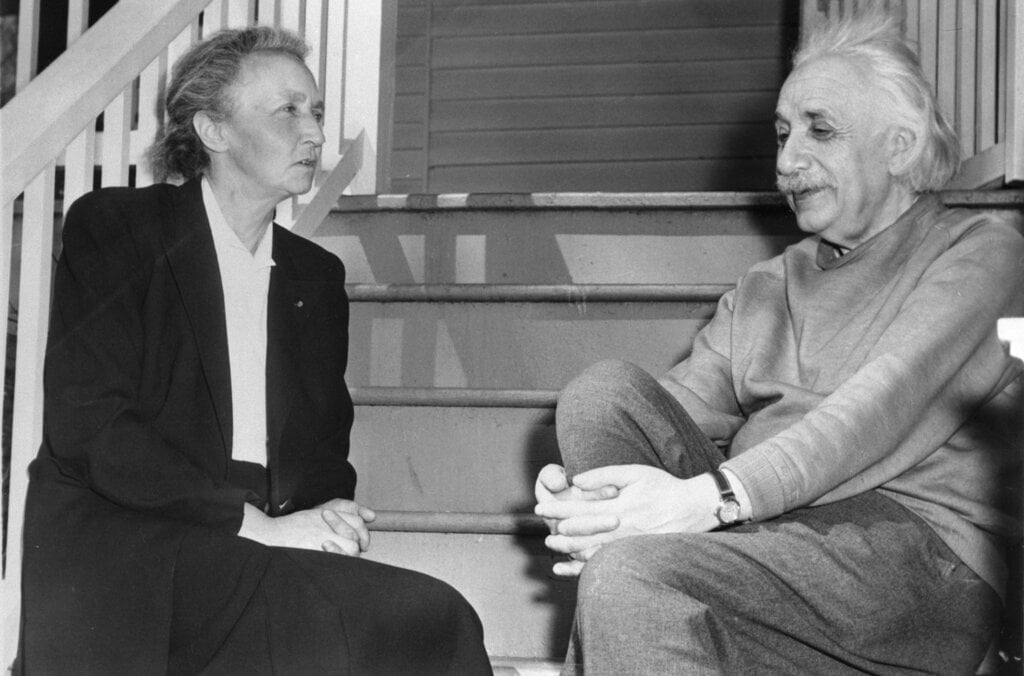

For discovering that radioactive atoms could be created artificially, the Joliot-Curies received the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1935. Joliot-Curie next helped conduct research into radium nuclei that led a separate group of German physicists to the discovery of nuclear fission, the splitting of the nucleus itself, and the vast amounts of energy emitted as a result. In 1946, she became director of the Radium Institute.

Photo: © Association Curie Joliot-Curie. Photographer unknown

After receiving the Nobel Prize, Joliot-Curie also turned her attention to her children – Hélène and Pierre – and to politics. Years before women could vote in France, she became the Undersecretary of State for Science, advocating for state funding of scientific research.

A member of the Comité National de l’Union des Femmes Françaises and of the World Peace Council she spoke against fascism and Nazism and in favour of women’s education. In 1939, fearful of how the military might use her research in nuclear fission, she and her husband locked their documentation in a vault.

Radioactivity can save lives but it can also kill. As her mother did before her, and her husband would just two years after, Joliot-Curie died of leukaemia caused by extensive exposure to radiation in 1956. She was 58 years old, still researching, still running the Institute, and still attending international conferences for peace and women’s rights – a citizen-scientist to the end.

Frédéric Joliot – Nobel Lecture

Nobel Lecture, December 12, 1935

Chemical Evidence of the Transmutation of Elements

Read the Nobel Lecture

Pdf 30 kB

Frédéric Joliot – Banquet speech

Frédéric Joliot’s speech at the Nobel Banquet in Stockholm, December 10, 1935 (in French)

Altesses Royales, Mesdames, Messieurs,

Qu’il me soit permis au nom de Madame Joliot-Curie et de moi-même d’exprimer toute notre admiration et notre reconnaissance à l’œuvre fondée par Alfred Nobel, de remercier les savants suédois du grand honneur qu’il nous ont fait en jugeant nos travaux dignes de la très haute distinction qu’est le Prix Nobel.

Que ce soit pour moi l’occasion de dire que si nous avons pu mener à bien nos recherches nous le devons aux maîtres qui formèrent notre pensée, je songe particulièrement en ce moment à notre regretté maître Marie Curie.

Nous retournerons bientôt en France reprendre nos travaux avec ardeur et nous serons soutenus dans cette tâche par le souvenir émouvant des belles journées que nous passons parmi vous.

Frédéric Joliot – Photo gallery

The 1935 Nobel Laureates at the Nobel Prize Award Ceremony in the Golden Hall of the Stockholm City Hall, 10 December 1935. From left: James Chadwick, Irène Joliot-Curie, Frédéric Joliot and Hans Spemann.

Photo: © Association Curie Joliot-Curie. Photographer unknown

Frédéric Joliot and Irène Joliot-Curie in the physics laboratory at the Radium Institute in France, 1935.

Photo: © Association Curie Joliot-Curie. Photographer unknown.

Frédéric Joliot and Irène Joliot-Curie in their physics laboratory at the Radium Institute in France, 1934.

Photo: © Association Curie Joliot-Curie. Photographer unknown

Irène Joliot-Curie – Nobel Lecture

Nobel Lecture, December 12, 1935

Artificial Production of Radioactive Elements

It is a great honour and a great pleasure to us that the Swedish Academy of Sciences has awarded us the Nobel Prize for our work on the synthesis of radio-elements, after having presented it to Pierre and Marie Curie in 1903, and to Marie Curie in 1911, for the discovery of the radio-elements.

I would like here to recall the extraordinary development of radioactivity, this new science which had its origin, less than forty years ago in the work of Henri Becquerel and of Pierre and Marie Curie.

It is known that the efforts of chemists of the last century established as a fundamental fact the extreme solidity of the atomic structures which go to make up the ninety-two known chemical species. With the discovery of the radio-elements, physicists found themselves for the first time confronted with strange substances, minute generators of radiation endowed with an enormous concentration of energy; alpha rays, positively charged helium atoms, beta rays, negatively charged electrons, both possessed of a kinetic energy which it would be impossible to communicate to them by human agency, and finally, gamma rays, akin to very penetrating X-rays. Chemists had no less astonishment as they recognized in these radioactive bodies, elements which had undergone modifications of the atomic structure which had been thought unalterable.

Each emission of an alpha or beta ray accompanies the transmutation of an atom; the energy communicated to these rays comes from inside the atom. As long as they continue to exist, radio-elements have well-defined chemical properties, like those of ordinary elements. These unstable atoms disintegrate spontaneously, some very quickly, others very slowly, but in accordance with unchanging laws which it has never been possible to interfere with. The time necessary for the disappearance of half the atoms, called the half-life, is a fundamental characteristic of each radio-element; according to the substance the value of the half-life varies between a fraction of a second and millions of years.

The discovery of radio-elements has had immense consequences in the knowledge of the structure of matter; the study of the materials themselves, and the study of the powerful effects produced on atoms by the rays they emit occupy scientific workers of numerous great research institutes in all countries.

Nevertheless, radioactivity remained a property exclusively associated with some thirty substances existing naturally. The artificial creation of radio-elements opens a new field to the science of radioactivity and so provides an extension of the work of Pierre and Marie Curie.

After the discovery of the spontaneous transmutations of radio-elements, the achievement of the first artificial transmutations is due to Lord Rutherford. Fifteen years later, by bombarding with alpha rays certain of the lighter atoms, nitrogen and aluminium for example, Lord Rutherford demonstrated the ejection of protons, or positively charged hydrogen nuclei; this hydrogen came from the bombarded atoms themselves: it was the result of a transmutation. The nature of the nuclear transformation could be firmly established: the aluminium atom, for example, captures the alpha particle and is transformed, after expelling the proton, into an atom of silicon. The amount of matter transformed cannot be weighed and the study of radiation alone has led to these conclusions.

In the course of recent years various artificial transmutations of different types have been discovered; some are produced by alpha rays, others by protons or deuterons, hydrogen nuclei of weight 1 or 2, others by neutrons, neutral particles of weight 1 about which Professor Chadwick has just spoken. The particles expelled when the atom explodes are protons, alpha rays or neutrons.

These transformations constitute true chemical reactions which act upon the innermost structure of the atom, the nucleus. They can be represented by simple formulae as Monsieur Joliot will be telling you in a moment.

I shall now speak to you of the experiments which have led us to obtain by transmutation new radioactive elements. These experiments have been made together by Monsieur Joliot and me, and the way in which we have divided this lecture between us is a matter of pure convenience.

In our study of the transmutations with emission of neutrons produced in the light elements irradiated with alpha rays, we have noticed some difficulties in interpretation in the emission of neutrons by fluorine, sodium, and aluminium. Aluminium can be transformed, by the capture of an alpha particle and the emission of a proton, into a stable silicon atom. On the other hand, if a neutron is emitted the product of the reaction is not a known atom.

Later on, we observed that aluminium and boron, when irradiated by alpha rays do not emit protons and neutrons alone, there is also an emission of positive electrons. We have assumed in this case that the emission of the neutron and the positive electron occurs simultaneously, instead of the emission of a proton; the atom remaining must be the same in the two cases.

It was at the beginning of 1934, while working on the emission of these positive electrons that we noticed a fundamental difference between that transmutation and all the others so far produced; all the reactions of nuclear chemistry induced were instantaneous phenomena, explosions. But the positive electrons produced by aluminium under the action of a source of alpha rays continue to be emitted for some time after removal of the source. The number of electrons emitted decreases by half in three minutes.

Here, therefore, we have a true radioactivity which is made evident by the emission of positive electrons.

We have shown that it is possible to create a radioactivity characterized by the emission of positive or negative electrons in boron and magnesium, by bombardment with alpha rays. These artificial radio-elements behave in all respects like the natural radio-elements.

Returning to our hypothesis concerning the transformation of the aluminium nucleus into a silicon nucleus, we have supposed that the phenomenon takes place in two stages: first there is the capture of the alpha particle and the instantaneous expulsion of the neutron, with the formation of a radioactive atom which is an isotope of phosphorus of atomic weight 30, while the stable phosphorus atom has an atomic weight of 31. Next, this unstable atom, this new radio-element which we have called “radio-phosphorus” decomposes exponentially with a half-life of three minutes.

We have interpreted in the same way the production of radioactive elements in boron and magnesium; in the first an unstable nitrogen with a half-life of II minutes is produced, and in the second, unstable isotopes of silicon and aluminium.

Irène Joliot-Curie – Other resources

Links to other sites

On Irène Joliot-Curie from American Institute of Physics

On Irène Joliot-Curie from Atomic Heritage Foundation

Irène Joliot-Curie – Nominations

Frédéric Joliot – Nominations

Irène Joliot-Curie – Photo gallery

Irene Joliot-Curie receiving her Nobel Prize from King Gustaf V of Sweden at Konserthuset Stockholm on 10 December 1935.

Photo: Bettmann/Getty Images

The 1935 Nobel Laureates at the Nobel Prize Award Ceremony in the Golden Hall of the Stockholm City Hall, 10 December 1935. From left: James Chadwick, Irène Joliot-Curie, Frédéric Joliot and Hans Spemann.

Photo: © Association Curie Joliot-Curie. Photographer unknown

Frédéric Joliot and Irène Joliot-Curie in the physics laboratory at the Radium Institute in France, 1935.

Photo: © Association Curie Joliot-Curie. Photographer unknown.

Frédéric Joliot and Irène Joliot-Curie in their physics laboratory at the Radium Institute in France, 1934. At this time they were working on the projection of nuclei, which was an essential step in the discovery of the neutron.

Photo: © Association Curie Joliot-Curie, Photographer unknown

Marie Curie and her daughter Irène in the laboratory at the Radium Institute in Paris, France, 1921.

Copyright © Association Curie Joliot-Curie Photographer unknown

Marie Curie and her daughter Irène at the Hoogstade Hospital in Belgium, 1915. Radiographic equipment is installed.

Copyright © Association Curie Joliot-Curie Photographer unknown

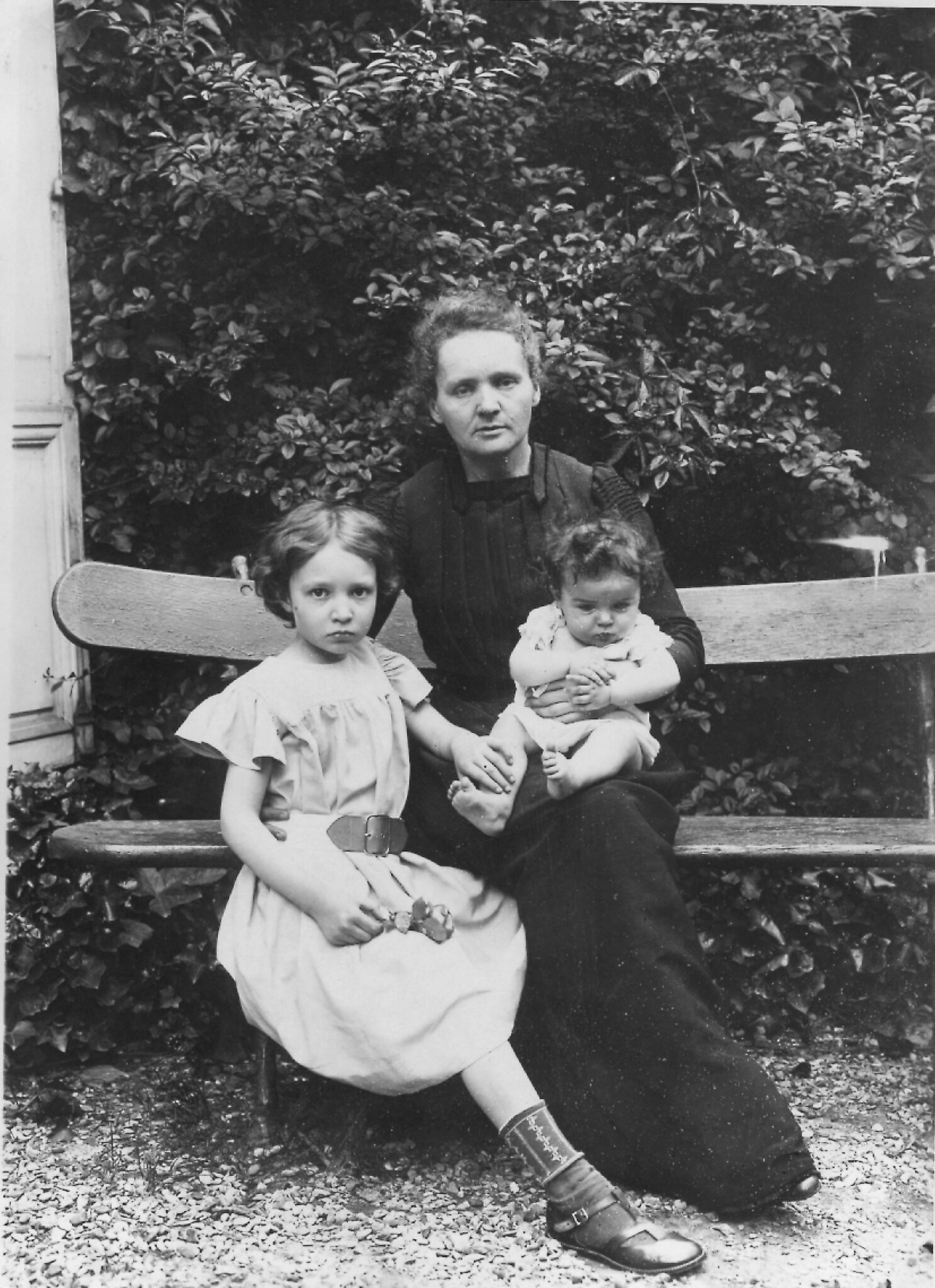

Marie Curie and her daughters Irène and Eve sitting on a bench in the garden (1905).

Copyright © Association Curie Joliot-Curie Photographer unknown

Frédéric Joliot – Biographical

Jean Frédéric Joliot, born in Paris, March 19, 1900, was a graduate of the Ecole de Physique et Chimie of the city of Paris. His father was Henri Joliot, a merchant, and his mother was Emilie Roederer. In 1925 he became, at the Radium Institute, assistant to Marie Curie, whose daughter Iréne he married in 1926. He obtained his Doctor of Science degree in 1930, having prepared a thesis on the electrochemistry of radio-elements, and became lecturer in the Paris Faculty of Science in 1935. At this time he carried out considerable research on the structure of the atom, generally in collaboration with his wife, Iréne Joliot-Curie. In particular they worked on the projection of nuclei, which was an essential step in the discovery of the neutron (Chadwick, 1932) and the positron (Anderson, 1932). However, their greatest discovery was artificial radioactivity (1934). By bombardment of boron, aluminium, and magnesium with alpha particles, they produced the isotope 13 of nitrogen, the isotope 30 of phosphorus and, simultaneously, the isotopes 27 of silicon and 28 of aluminium. These elements, not found naturally, decompose spontaneously, with a more or less long period, by emission of positive or negative electrons. It was for this very important discovery that these two physicists received in 1935 the Nobel Prize for Chemistry. During this time F. Joliot, who had always taken an interest in social questions, joined the Socialist Party, the S.F.I.O. (1934), then the League for the Rights of Man (1936)

In 1937 he was nominated Professor at the Collège de France. He left the Radium Institute and had built for his new laboratory of nuclear chemistry the first cyclotron in Western Europe. After the discovery of the fission of the uranium nucleus, he produced a physical roof of the phenomenon; then with Hans Halban and Lev Kowarski, joined by Francis Perrin, he worked on chain reactions and the requirements for the successful construction of an atomic pile using uranium and heavy water; five patents were taken out in 1939 and 1940. On the advance of the German forces (1940), F. Joliot managed to get the documents and materials relating to this work transported to England. During the French occupation he took an active part in the Resistance; he was President of the National Front and formed the French Communist Party. After having been Director of the Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique (1945), he became the first High Commissioner for Atomic Energy (1946); he directed the construction of the first French atomic pile (1948). He was relieved of his duties in 1950 for political reasons. While still retaining the control of his laboratories, F. Joliot-Curie took a considerable part in politics and was elected President of the World Peace Council. On the death of Irene Joliot-Curie, in 1956, he became, while still retaining his professorship at the Collège de France, holder of the Chair of Nuclear Physics which she had held at the Sorbonne.

F. Joliot was a member of the French Academy of Sciences and of the Academy of Medicine. He was also a member of numerous foreign scientific academies and societies, and holder of an honorary doctor’s degree of several universities. He was a Commander of the Legion of Honour. His recreations show him as a man of wide attainments, among which piano playing, landscape painting and reading (particularly Kipling), were predominant.

Joliot devoted the last two years of his life to the inauguration and development of a large centre for nuclear physics at Orsay. He died in Paris in 1958.

Jean Frederic and Irene Joliot-Curie had one daughter, Helene, and one son, Pierre.

This autobiography/biography was written at the time of the award and first published in the book series Les Prix Nobel. It was later edited and republished in Nobel Lectures. To cite this document, always state the source as shown above.

Frédéric Joliot died on August 14, 1958.