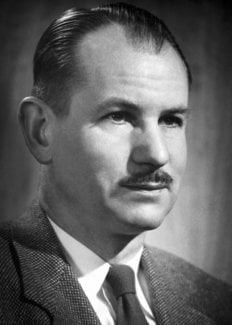

Glenn T. Seaborg – Photo gallery

1 (of 2) Glenn T. Seaborg standing in front of the Periodic Table with the Ion Exchanger illusion column of Actnide Elements, May 19, 1950.

Photo courtesy of Berkeley Lab

2 (of 2) Chemistry laureate Glenn T. Seaborg (middle) and his wife Helen converse with physics laureate Manne Siegbahn during the Nobel Week in Stockholm, Sweden, 9 December 1951.

Photographer unknown. Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Glenn T. Seaborg – Banquet speech

Glenn T. Seaborg’s speech at the Nobel Banquet in Stockholm, December 10, 1951 (in Swedish)

Ers Majestät, Era Kungliga Högheter, mina damer och herrar:

Jag ska försöka att säga några ord på svenska. Nobelpriset har ett högt värde hos vetenskapsmän i hela världen. Ja, det är den största ära som en forskare kan få. Varför har det blivit så? Det är inte för pengarnas skull. Man ska se på en lista över de upptäckter som har fått Nobelpriset under alla år. Då ser man hur väl svenska vetenskapsakademien har gjort sitt jobb.

Det svenska kungahuset har också hjälpt till att ge priset värde genom att kungen själv delat ut priset.

Jag är mycket tacksam för att jag och mina medarbetare har kunnat göra sådana upptäckter att vetenskapsakademien har velat belöna dem med Nobelpris. Jag vill bara hoppas att de nya grundämnen vi har funnit kommer att bli till gott for världen.

Och till sist vill jag tacka akademin for att den velat ära mig och mina medarbetare så som den gjort.

Prior to the speech, Einar Löfstedt, member of the Royal Academy of Sciences, addressed the laureate: “The same is true, Professor McMillan and Professor Seaborg, of your discoveries and achievements in nuclear chemistry. You have succeeded in augmenting the well-known periodical system with no less than six new elements. The result is, even for the layman, imposing in itself; in addition, among the many new kinds of atoms you have produced, are those which can be used for generating atomic energy – let it be noted, not merely for military, but also for peaceful ends. This is a vast perspective for future development which opens up before the imagination. We beg you too to accept our most sincere homage, and we are very happy that you have honoured this festival with your presence. And although the Nobel Prizes should be, and are, awarded regardless of nationality, race or creed, I may perhaps be allowed to stress the warmth of our greeting to you, Professor Seaborg, now that you, crowned with laurels, are visiting the land of your mother and your forefathers – a very old kingdom with a very modern democracy and a very keen interest in the progress of research and civilization.”

Edwin M. McMillan – Nobel Lecture

Nobel Lecture, December 12, 1951

The Transuranium Elements: Early History

Read the Nobel Lecture

Pdf 100 kB

Glenn T. Seaborg – Nobel Lecture

Nobel Lecture, December 12, 1951

The Transuranium Elements: Present Status

Read the Nobel Lecture

Pdf 533 kB

Edwin M. McMillan – Banquet speech

Edwin M. McMillan’s speech at the Nobel Banquet in Stockholm, December 10, 1951

Your Majesty, Your Royal Highnesses, Ladies and Gentlemen.

I would like to say how much I appreciate this honor and how deeply impressed I am by this ceremony and by what it represents. There has never been in the history of the world any other prize or honor with the international recognition accorded to the Nobel Prize. One reason for this is that it is truly an international honor, given with regard to achievement only. It is very greatly to the credit of the Swedish and Norwegian nations, and to the organizations and individuals in those nations who have administered the giving of the Prizes, that this high ideal of Alfred Nobel has been maintained. The world would be a more agreeable place if similar ideals governed more of its affairs.

Prior to the speech, Einar Löfstedt, Member of the Royal Academy of Sciences, addressed the laureate: “The same is true, Professor McMillan and Professor Seaborg, of your discoveries and achievements in nuclear chemistry. You have succeeded in augmenting the well-known periodical system with no less than six new elements. The result is, even for the layman, imposing in itself; in addition, among the many new kinds of atoms you have produced, are those which can be used for generating atomic energy – let it be noted, not merely for military, but also for peaceful ends. This is a vast perspective for future development which opens up before the imagination. We beg you too to accept our most sincere homage, and we are very happy that you have honoured this festival with your presence.”

Edwin M. McMillan – Other resources

Links to other sites

‘Edwin M. McMillan, Neptunium, Phase Stability, and the Synchrotron’ from DOE R&D Accomplishments

On GLenn Seaborg and Edwin McMillan from Berkeley Laboratories

Glenn T. Seaborg – Other resources

Links to other sites

On Glenn T. Seaborg from Glenn T. Seaborg Institute

Interview with Glenn Seaborg from PBS Frontline

On Glenn T. Seaborg from U.S. Department of Energy

On Glenn Seaborg from Berkeley Laboratories

Glenn T. Seaborg – Nominations

Edwin M. McMillan – Nominations

Edwin M. McMillan – Biographical

Edwin Mattison McMillan was born on 18th September, 1907, at Redondo Beach, California. He is the son of Dr. Edwin Harbaugh McMillan, a physician, and his wife, Anne Marie McMillan, née Mattison, who both came from the State of Maryland and were both of English and Scottish descent. The boy spent his early years in Pasadena, California, and obtained his education in that state.

McMillan attended the California Institute of Technology, obtaining a B.Sc. degree in 1928, and taking his M.Sc. degree a year later, then transferring to Princeton University for Ph.D. in 1932. The same year he entered the University of California at Berkeley as a National Research Fellow. The thesis he submitted for Ph.D. was in the field of molecular beams, and the problem he undertook as a National Research Fellow was the measurement of the magnetic moment of the proton by a molecular beam method. After two years on this work and one as a research associate he became a Staff Member of the Radiation Laboratory under Professor E.O. Lawrence, studying nuclear reactions and their products, and helping in the design and construction of cyclotrons and other equipment, and a member of the Faculty in the Department of Physics at Berkely, being appointed Instructor in 1935, Assistant Professor in 1936, Associate Professor, 1941, and Professor in 1946.

During the Second World War, McMillan was on leave from November, 1940, to September, 1945, engaged on national defence research, serving (1940-1941) in the Radiation Laboratory, Massachusetts Institute of Technology; (1941-1942) U. S. Navy Radio and Sound Laboratory, San Diego; (1942-1945) Manhattan District, Los Alamos.

It was during 1945 that he had the idea of “phase stability” which led to the development of the synchroton and synchro-cyclotron; these machines have already extended the energies of artificially accelerated particles into the region of hundreds of MeV and have made possible many important researches.

McMillan returned to the University of California Radiation Laboratory as Associate Director from 1954-1958, when he was raised to Deputy Director and finally Director, in the same year.

In 1951 he received the 1950 Research Corporation Scientific Award, and in 1963 he shared the Atoms for Peace Award with Professor V. I. Veksler.

Professor McMillan is a Fellow of the American Physical Society and the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, a member of the National Academy of Sciences and the American Philosophical Society, and from 1954-1958 he served on the General Advisory Committee to the Atomic Energy Commission. In 1960 he was appointed to the Commission on High Energy Physics of the International Union of Pure and Applied Physics.

An honorary doctorate in science was awarded to him by the Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute in 1961, and by Gustavus Adolphus College in 1963.

While serving in the Faculty of Physics at Berkeley, McMillan married Elsie Walford Blumer, a daughter of Dr. George Blumer, Dean Emeritus of the Yale Medical School. There are three children of the marriage – Ann Bradford (1943), David Mattison (1945) and Stephen Walker (1949).

This autobiography/biography was written at the time of the award and first published in the book series Les Prix Nobel. It was later edited and republished in Nobel Lectures. To cite this document, always state the source as shown above.

Edwin M. McMillan died on September 7, 1991.