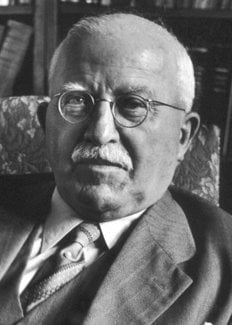

Hermann Staudinger – Photo gallery

1 (of 1) From left: Medecine laureate Fritz Lipmann with his wife Elfreda, physics laureate Frits Zernike and chemistry laureate Hermann Staudinger with his wife Magda at the Nobel Banquet, 10 December 1953.

Photographer unknown. Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Hermann Staudinger – Other resources

Links to other sites

‘Hermann Staudinger and the Foundation of Polymer Science’ from ACS

On Hermann Staudinger from Science History Institute

Hermann Staudinger – Nobel Lecture

Nobel Lecture, December 11, 1953

Macromolecular Chemistry

Read the Nobel Lecture

Pdf 244 kB

Hermann Staudinger – Banquet speech

Hermann Staudinger’s speech at the Nobel Banquet in Stockholm, December 10, 1953 (in German)

Majestät, Königliche Hoheiten, Excellenzen, Hochansehnliche Festversammlung,

Durch das Vermächtnis Alfred Nobels sind dank der grossen Bemühungen der Königlich Schwedischen Akademie der Wissenschaften und des Karolinischen Institutes Verbindungen unter den Wissenschaftlern der verschiedensten Länder hergestellt worden, die auf Grund ihrer wissenschaftlichen Leistungen für würdig zum Empfang des Nobelpreises befunden wurden. Es ist so eine weltweite Gemeinschaft von Nobelpreisträgern infolge des Wirkens dieser beiden Institutionen in den letzten 50 Jahren ins Leben gerufen worden. Es bedeutet für mich eine grosse Ehre, in diese Gemeinschaft durch Verleihung des Nobelpreises aufgenommen zu sein, und für die makromolekulare Chemie, deren Bedeutung Herr Professor Fredga bei der Überreichung des Preises geschildert hat, ist es eine hohe Anerkennung, dass sie durch die grösste Auszeichnung geehrt wurde, die die wissenschaftliche Welt zu vergeben hat. Für diese hohe Ehre spreche ich den Mitgliedern der Königlich Schwedischen Akademie der Wissenschaften und der Nobel-Stiftung meinen tiefempfundenen, wärmsten Dank aus. Dies tue ich nicht nur in meinem Namen, sondern auch im Namen meiner Frau, der langjährigen Mitarbeiterin auf diesem Gebiet.

Nachdem ich schon in Karlsruhe, angeregt durch die Arbeiten von Karl Engler, Untersuchungen über die Beziehungen von Autoxydation und Polymerisation durchführte, beschäftigte ich mich von 1920 ab an der Eidgenössischen Technischen Hochschule in Zürich eingehender mit diesen damals viel diskutierten Fragen. An diese Zeit denke ich gerne zurück, weil dort im Widerstreit mit den herrschenden Meinungen die ersten Grundlagen für die makromolekulare Chemie gelegt wurden. Diese Untersuchungen sind dann von 1926 ab im chemischen Institut der Universität Freiburg i. Br. und schliesslich nach meiner Emeritierung im Staatlichen Forschungsinstitut für makromolekulare Chemie in Freiburg i. Br. weiter fortgeführt worden, und ich hoffe, dass sie durch die Verleihung des Nobelpreises jetzt noch mehr gefördert werden.

Die technisch wichtigen Fragen der makromolekularen Chemie, die Fragen der Faser- und Kunststoffherstellung, werden heute in der ganzen Welt auf das intensivste bearbeitet. In wissenschaftlicher Hinsicht eröffnet die makromolekulare Chemie ausserdem noch neue Ausblicke für die Biologie. Je mehr wir in diese Fragen eindringen, umso wunderbarer erscheint uns das Lebendige durch die Vielgestaltigkeit seiner makromolekularen Architektonik. Möge durch diese Forschungen Arbeit geleistet werden im Sinne Alfred Nobels, der die Hoffnung hatte, durch die Förderung der Wissenschaft zum Wohle der Menschheit beizutragen.

Prior to the speech, G. Liljestrand, Member of the Royal Academy of Sciences, addressed the laureate: Während der letzten Jahre seines Lebens war Alfred Nobel eifrig bemüht, ein künstliches Ersatzmittel für Kautschuk zu finden. Dies gelang ihm nicht. Erst einige Jahrzehnte später wurde das Problem gelöst, als das umfassende und wichtige Gebiet der Makromoleküle erschlossen wurde. Jetzt spielen die syntetischen makromolekularen Produkte eine höchst wichtige Rolle in unserem täglichen Leben. Wir begrüssen Sie, Herr Professor Staudinger, als einen Pionier dieser neuen Wissenschaft, die Sie mit zahlreichen Entdeckungen bereichert haben. Mit zielbewusster und zäher Energie haben Sie das Fundament unserer heutigen Auffassung dieses Gebietes geschaffen. Wir sprechen Ihnen unsere Bewunderung für Ihre Leistungen aus.

Hermann Staudinger – Nominations

Award ceremony speech

Presentation Speech by Professor A. Fredga, member of the Nobel Committee for Chemistry of the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences

Your Majesties, Royal Highnesses, Ladies and Gentlemen.

“Even the ancient Greeks…” is a frequent preamble to the survey of a historical event and the hearer sees a vision of frightening profundity. I should like today to begin with Democritus of Abdera who formulated the first atomistic conception of the world and thus created the first atomic concept. However, the meaning of this concept did not become more closely defined until about 1800 by the Englishman Dalton who assumed that each element had its specific type of mutually identical atoms. In the formation of a chemical compound a number of atoms of two or more elements are linked together by chemical bond forces into particles for which the Italian Avogadro introduced the name molecules. In the second half of last century through the work of the German Kekulé and the Dutchman van ‘t Hoff, knowledge was gained of important principles in the architecture of the molecules. The relative positions of the atoms have been determined to a certain extent; they link one another together to form chains, simple or branched, or to form more complex structures. Both molecules and atoms, however, were purely hypothetical concepts at that time; not until the turn of the century was definite proof of their actual existence forthcoming, and so it became possible to determine their actual size and mass. As expected they were found to be very small. The number of molecules in one litre of water is expressed by a number containing 26 digits.

It was often wondered how many atoms could be combined in one molecule, to what degree this compression of matter could be taken, to use the phrase with which the situation was expressed by a leading research worker of the day. The fact that the atoms in the molecule are held together by chemical bond forces is closely related to the question of the strength of the chemical bond, of which only little was known. On the one hand it was known that the molecules of apparently very stable compounds could readily be split by electrolytic dissociation, on the other hand there was a dawning realization that chemical forces had a profound bearing on the structure of solid crystals. Molecules with one to two hundred atoms had been built in stages and this fact was considered remarkable. There was an eagerness to experiment, to advance further, but it was believed that little more could be achieved in this way.

In the early 1920’s Professor Staudinger expressed the view that a molecule could be very large, almost arbitrarily large in fact, that such macromolecules could very easily, sometimes with apparent spontaneity, be formed of 10,000 or 100,000 atoms and that the particles of colloidal solutions were in many cases actual molecules of this type. I shall attempt to reproduce his trend of argument.

In organic chemistry it not infrequently occurs that sparingly soluble or insoluble resinous or pitch-like masses are obtained instead of the product expected; occasionally a change of this type occurs without visible cause. All the indications are that in some way the molecules become joined together. Such products were usually designated high polymer or high molecular substances but for many reasons there was a desire to regard the phenomenon as a physical one. On the other hand numerous cases were known where a small number of molecules, perhaps two or three, united to yield a larger molecule with a ring structure. Professor Staudinger pointed out that the formation of high molecular substances occurs where ring closure is expected in principle but is hindered for geometric reasons or, in other words, in cases where the ends of the atomic chains only meet with difficulty. Here, however, the chain ends must link up with other molecules which in turn capture new molecules and so the chain grows until the process is interrupted by some external circumstance, perhaps because the material is exhausted. The high molecular products were thus alleged to consist of chains formed in this way and since there can scarcely be any doubt that the ring molecules just referred to have been created by means of normal chemical bond forces, such must also be the case with the chains.

This argument, which strikes us nowadays as completely obvious, was very strange in the early 1920’s, running partly counter to the spirit of the period, and the next ten years were charged with controversy. It was theoretically very difficult and practically very laborious to find decisive evidence or counter-evidence. For the time being it was impossible to determine the molecular weights of the magnitudes involved here but it was considered that the new theory placed impossible demands on the strength of the chemical bond forces. Concepts and definitions had to be revised, including the chemical compound concept. Categories of compounds had to be recognized in which the molecules are not completely identical. The high molecular compounds consist of chain molecules constructed according to a common pattern and often with a characteristic average length but the length of the individual chains depends upon arbitrary circumstances. The new theory was not universally recognized until the 1930’s.

The macromolecular theory had then already been adopted in technology. People learned to use the strong giant molecules for the manufacture of what are nowadays commonly termed plastics. Isolated products of this type had been known previously but now theoretical principles for further work, with almost limitless possibilities for varying the properties of the material according to different requirements were available, and so in the 1930’s and 1940’s a powerful growth came about in this sector. We are aware that in many respects this development has laid its imprint on the modern material culture; it is indeed stated that we are living in the age of plastics. For pure science too, however, the macromolecular theory has been of the greatest significance.

An impressive number of workers have been active in the macromolecular field during the last decennia. Professor Staudinger has not been involved directly in the technical and industrial development but without his energetic and bold pioneering work this development would scarcely be conceivable.

Professor Staudinger. More than thirty years ago you expressed the view that a chemical molecule can attain an almost arbitrary size and that such macromolecules are of great importance in our world. Your view was based on logical reasoning. You drew attention to the fact that what are termed high polymers are formed when for some reason or another an anticipated ring closure fails to occur. You thus submitted an argument which an organic chemist cannot ignore. Moreover, in extensive and painstaking series of studies you have provided experimental proof.

It is no secret that for a long time many colleagues rejected your views which some of them even regarded as abderitic. This was understandable perhaps. In the world of high polymers almost everything was new and untried. Long standing, established concepts had to be revised or new ones created. The development of the macromolecular science does not present a picture of a peaceful idyll.

As time passed, the conflicts vanished and the controversies were stilled. Unity has been achieved on the major issues and the importance of your pioneering work has become more and more apparent. In recognition of your services to the natural science and the material culture made possible by your discoveries in the field of high molecular compounds, the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences has resolved to award you the Nobel Prize for this year. I congratulate you on behalf of the Academy and would ask you to receive the Nobel Prize from the hands of His Majesty the King.

The Nobel Prize Award Ceremony 1953

Speed read: Connecting on a grand scale

What links natural products like rubber and cellulose with artificial plastics is that they are made up from extraordinarily large molecules. The idea of how these molecules originate or are formed was believed to be set in stone, until Hermann Staudinger provided an audacious concept that in time helped to unravel their structural secrets.

Staudinger’s proposal about the structure of large molecules appeared in a paper published in 1920, during the course of his studies on the chemistry of rubber. He argued that he found little evidence for the conventional wisdom, which stated that molecules can only reach a certain maximum size, and that somehow small molecules clump together in glue-like aggregates to give the false impression that they are giant molecules. Contrary to this view, Staudinger proposed that these molecules are in fact made from giant chain-like compounds, which are formed by links of short repeating molecular units joined through chemical interactions, and that these could be constructed to almost any length.

Working against a constant background of intense scepticism, Staudinger spent almost a decade meticulously piecing together indirect evidence for what he termed macromolecular compounds; for instance, by looking at the way they reacted and their viscosity in solution. Direct evidence to support Staudinger’s hypothesis finally arrived when Herman Mark visualized long chains of repeated units using X-rays, and Wallace Carothers showed that artificial materials like nylon and polyester could be stitched together from repeated small units using chemical reactions regularly carried out in the laboratory.

Staudinger’s pioneering ideas laid the foundation for the modern plastics industry, with chemists able to modify elements in chemical chains to create new artificial materials for a host of uses. Staudinger’s work also provided the basis for studying the chemistry of the macromolecules found in living organisms, such as the proteins and DNA that are the vital building blocks for all life on Earth.

The Nobel Prize in Chemistry 1953

Hermann Staudinger – Biographical

Hermann Staudinger was born in Worms on the 23rd of March 1881. His father was Dr. Franz Staudinger.

Staudinger was educated in Worms, matriculated in 1899, and continued his studies first at the University of Halle, later at Darmstadt and Munich. He graduated at Halle in 1903 and qualified for inauguration as academic lecturer under Professor Thiele at Strasbourg University in spring 1907. In November 1907 he was appointed Professor of Organic Chemistry at the Institute of Chemistry of the Technische Hochschule in Karlsruhe. For fourteen years, from 1912, he was lecturer at the Eidgenössische Technische Hochschule in Zurich, and in 1926 followed the invitation of the University of Freiburg i. Br. to become Lecturer of Chemistry. ln this city, he remained all through his further career. From 1940 onwards he held an additional appointment as Principal of the Research Institute for Macromolecular Chemistry. Staudinger resigned from his post as Principal of the Chemical Laboratories of the University in April 1951, and accepted the honorary appointment as Head of the State Research Institute for Macromolecular Chemistry, which he held until April 1956.

Staudinger was a prolific writer and the following books by him have been published: Die Ketene (Ketenes), published by Enke, Stuttgart, 1912; Anleitung zur organischen qualitativen Analyse (Introduction to organic qualitative analysis), published by Springer, Berlin, 1st edition 1923, 5th edition 1948, 6th edition 1955; Tabellen zu den Vorlesungen über allgemeine und anorganische Chemie (Tables for the lectures on general and inorganic chemistry), published by Braun, Karlsruhe, 1st edition 1927, 5th edition 1947; Die hochmolekularen organischen Verbindungen, Kautschak und Cellulose (The high-molecular organic compounds, rubber and cellulose), published by Springer, Berlin, 1932; Organische Kolloidchemie (Organic colloid chemistry), published by Vieweg, Braunschweig, 1st edition 1940, 3rd edition 1950; Fortschritte der Chemie, Physik und Technik der makromolekularen Stoffe (Progress of the chemistry, physics and technique of the macromolecular substances), jointly with Professor Vieweg and Professor Röhrs, Volume 1, 1939, Volume II, 1942, publisher Lehmann, Munich; Makromolekulare Chemie und Biologie (Macromolecular chemistry and biology), publisher Wepf & Co., Basle, 1947; Vom Aufstand der technischen Sklaven (The uprising of the technical slave), published by Chamier, Essen-Freiburg, 1947.

Since September 1947 Staudinger has edited the periodical Die makromolekulare Chemie (Macromolecular chemistry), published by Dr. A. Hüthig, Heidelberg and Wepf & Co., Basle.

In 1961 his book Arbeitserinnerungen (Working memoirs) appeared, published by Dr. A. Hüthig, Heidelberg.

Besides the books, Staudinger published a great number of scientific papers. Among these were fifty on ketenes, also works on oxalyl chloride, autoxidation, aliphatic diazo-compounds, explosions, insecticides, synthetic pepper and coffee aroma. Since 1920 he has written approximately 500 papers on macromolecular compounds, about 120 of these on cellulose, about 50 on rubber and isoprene.

For his work Staudinger received many honours and awards; to mention but a few – he is Dr. Ing. h.c. of the Technische Hochschule Karlsruhe; Dr. rer. nat. h.c. of the University of Mainz; Dr. (C) h.c. of the University of Salamanca; Dr. chem. h.c. of the University of Torino; Dr. sc. techn. h.c. of the Eidgenössische Technische Hochschule Zurich; and Dr. h.c. of the University of Strasbourg. In 1953 he was awarded the Nobel Prize in Chemistry for his discoveries in the field of macromolecular chemistry. In 1933 he was honoured with the Cannizzarro Prize of the Reale Accademia Nazionale dei Lincei in Roma. He is member of the Institut de France, and member and honorary member of many Chemical Societies and the Society of Macromolecular Chemistry in Tokyo.

Hermann Staudinger is married to Magda Woit, who is for many years his co-worker and co-author of numerous publications.

This autobiography/biography was written at the time of the award and first published in the book series Les Prix Nobel. It was later edited and republished in Nobel Lectures. To cite this document, always state the source as shown above.

Hermann Staudinger died on September 8, 1965.