Richard E. Smalley – Photo gallery

Richard E. Smalley receiving his Nobel Prize from H.M. King Carl XVI Gustaf of Sweden at the Stockholm Concert Hall on 10 December 1996.

Nobel Foundation. Photo: Lars Åström

Richard E. Smalley after receiving his Nobel Prize from King Carl XVI Gustaf of Sweden at the Nobel Prize award ceremony, 10 December 1996.

Photo from the Lars Åström archive

All laureates assembled at the Nobel Prize award ceremony in the Stockholm Concert Hall on 10 December 1996. From left: physics laureates David M. Lee, Douglas D. Osheroff and Robert C. Richardson, chemistry laureates Robert F. Curl Jr., Sir Harold W. Kroto and Richard E. Smalley, medicine laureates Peter C. Doherty and Rolf M. Zinkernagel, literature laureate Wislawa Szymborska and economic sciences laureate James A. Mirrlees.

Photo from the Lars Åström archive

Richard E. Smalley showing his Nobel Prize medal after the Nobel Prize award ceremony in Stockholm, Sweden on 10 December 1996.

Photo from the Lars Åström archive

Richard E. Smalley at the Nobel Prize banquet in the Stockholm City Hall, 10 December 1996.

Nobel Foundation. Photo: Lars Åström

Richard E. Smalley at the Nobel Banquet on 10 December 1996.

Photo from the Lars Åström archive

Richard E. Smalley on the dance floor at the Nobel Prize banquet on 10 December 1996.

Nobel Foundation. Photo: Lars Åström

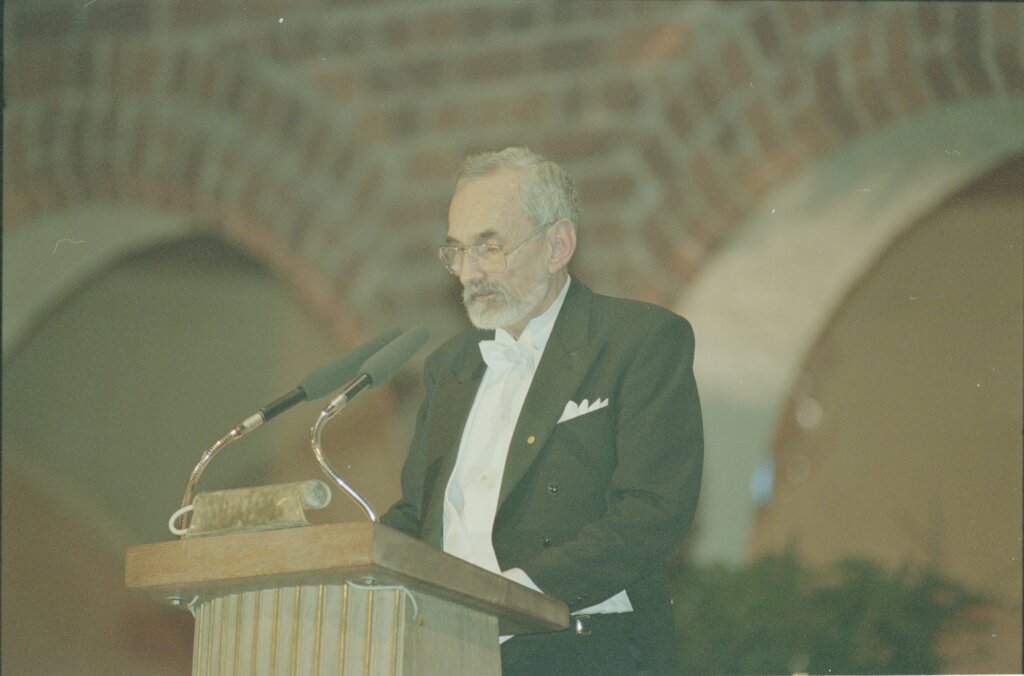

Richard E. Smalley delivering his Nobel Prize lecture on 7 December 1996.

Photo from the Lars Åström archive

Chemistry laureates Harry Kroto, Robert Curl and Richard Smalley in 1996.

Photo: Boo Jonsson

Chemistry laureates Robert F. Curl Jr., Sir Harold Kroto and Richard E. Smalley at a press conference, December 1996.

Photo: Boo Jonsson

Ten Nobel Laureates of 1996 assembled in Stockholm in December 1996. Back row: Sir Harold W. Kroto, Douglas D. Osheroff, Rolf M. Zinkernagel, James A. Mirrlees, Robert F. Curl Jr. and Richard E. Smalley. Front row: Peter C. Doherty, Wisława Szymborska, David M. Lee and Robert C. Richardson.

Photo from the Lars Åström archive

Richard E. Smalley photographed during Nobel Week in Stockholm, Sweden, December 1996.

Nobel Foundation. Photo: Lars Åström

Nine Nobel Laureates of 1996 assembled in Stockholm in December 1996. Back row: Sir Harold W. Kroto, Rolf M. Zinkernagel, Richard E. Smalley. Peter C. Doherty, Douglas D. Osheroff. Front row: James A. Mirrlees, Robert F. Curl Jr., David M. Lee and Robert C. Richardson.

Nobel Foundation. Photo: Lars Åström

Robert F. Curl Jr.- Photo gallery

Robert F. Curl Jr. receiving his Nobel Prize from King Carl XVI Gustaf of Sweden at the Nobel Prize award ceremony, 10 December 1996.

Photo from the Lars Åström archive

All laureates assembled at the Nobel Prize award ceremony in the Stockholm Concert Hall on 10 December 1996. From left: physics laureates David M. Lee, Douglas D. Osheroff and Robert C. Richardson, chemistry laureates Robert F. Curl Jr., Sir Harold W. Kroto and Richard E. Smalley, medicine laureates Peter C. Doherty and Rolf M. Zinkernagel, literature laureate Wislawa Szymborska and economic sciences laureate James A. Mirrlees.

Photo from the Lars Åström archive

Robert F. Curl Jr. with his Nobel Prize after the award ceremony, 10 December 1996.

Photo from the Lars Åström archive

Robert F. Curl Jr. proceeds into the Blue Hall of the Stockholm City Hall for the Nobel Banquet, 10 December 1996.

Photo from the Lars Åström archive

Robert F. Curl Jr. at the Nobel Banquet, 10 December 1996.

Photo from the Lars Åström archive

Robert F. Curl Jr at the Nobel Prize banquet in the Stockholm City Hall, 10 December 1996.

Nobel Foundation. Photo: Lars Åström

Robert F. Curl delivering his speech of thanks at the Nobel Prize banquet in the Stockholm City Hall, 10 December 1996.

Photo from the Lars Åström archive

Chemistry laureates Harry Kroto, Robert Curl and Richard Smalley in 1996.

Photo: Boo Jonsson

Robert F. Curl Jr. delivering his Nobel Prize lecture on 7 December 1996.

Photo from the Lars Åström archive

Chemistry laureates Robert F. Curl Jr., Sir Harold Kroto and Richard E. Smalley at a press conference, December 1996.

Photo: Boo Jonsson

From left: David M. Lee, Robert C. Richardson, Douglas D. Osheroff, Robert F. Curl Jr and Sir Harold Kroto during a press conference in Stockholm, Sweden, December 1996.

Nobel Foundation. Photo: Lars Åström

Ten Nobel Laureates of 1996 assembled in Stockholm in December 1996. Back row: Sir Harold W. Kroto, Douglas D. Osheroff, Rolf M. Zinkernagel, James A. Mirrlees, Robert F. Curl Jr. and Richard E. Smalley. Front row: Peter C. Doherty, Wisława Szymborska, David M. Lee and Robert C. Richardson.

Photo from the Lars Åström archive

Nine Nobel Laureates of 1996 assembled in Stockholm in December 1996. Back row: Sir Harold W. Kroto, Rolf M. Zinkernagel, Richard E. Smalley. Peter C. Doherty, Douglas D. Osheroff. Front row: James A. Mirrlees, Robert F. Curl Jr., David M. Lee and Robert C. Richardson.

Nobel Foundation. Photo: Lars Åström

The Nobel Prize in Chemistry 1996

Harold Kroto – Interview

Harry Kroto Answers Questions on the NobelPrize YouTube Channel

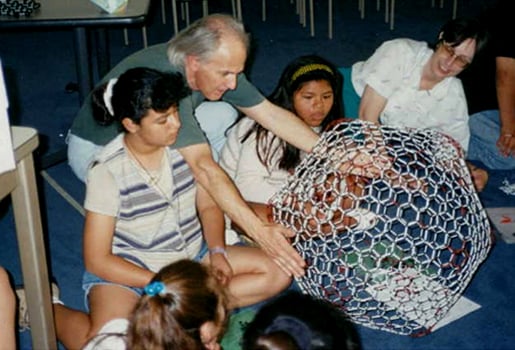

The fourth in a series of Q&A sessions with Nobel Laureates on YouTube features Harry Kroto, who received the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1996 for discovering that carbon atoms can assemble into soccer-ball-shaped structures of molecules, known as fullerenes or buckyballs. In the videos below he responds to a selection of questions posted on the NobelPrize YouTube channel. His answers reveal his interest in graphic design, his memories of discovering C60, and his views on the future of nanoscience and science education more generally.

Interview transcript

This is Sir Harold Kroto who got the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1996 for the discovery of fullerenes. I’m Astrid Gräslund, Secretary of the Nobel Committee for Chemistry, and also Professor of Biophysics at Stockholm University. I would like to ask you some questions. I would like to begin by asking you a little about your background. Where you grew up and where you went to school and then how you became interested in natural sciences.

Sir Harold Kroto: I was bought up in Bolton. Moderate size in the north of England, just north of Manchester. My parents were refugees. My parents were born in Berlin and came to England in 1937 as refugees. I was born in 1939 in the first year of the war. The first month of the war. My parents ended up in Bolton which was a mining and cotton town. There was mining in the area but also weaving which during the period of the decline of the spinning and weaving industry in the UK came into hard times. I lived in the poorer parts of the town because my parents lost more or less everything.

I had a pretty good childhood although we didn’t have very much. I was an only child. I went to school and I quite liked school because it seemed better than where I was living. I quite enjoyed going to school. And my parents being refugees really worked very hard to make sure that I did my homework. I wasn’t allowed to go to bed until my homework was finished and if it wasn’t finished by 12 o’clock my father would finish it off for me. And after a while he was not getting such good marks as I was, so I thought it was time that I would do it by myself.

When I was about 14 or 15 I would work in the factory. I could do everything.

When I was about 14 or 15 I would work in the factory. I could do everything.My father was a balloon maker. In Germany in Berlin, before the war, he had printed faces on balloons. When he came to England he lost everything. He became an engineer. I don’t know how he managed it. I know a little bit about it. He tried to build up a factory in 1955 to make balloons and he was helped by his old friends in Germany who had made the balloons before. He set up a company in 1955 to make and print balloons. When I was about 14 or 15 I would work in the factory. I could do everything. I think that was extremely good training. You wouldn’t be allowed to do this now, because it would be against the safety acts and factory acts. But I could do almost everything. I could repair things. Drill holes. If the machinery stopped I could fix that. I could clean the boiler, which was a big boiler, about half the size of this room. I could take the jets out of the oil pressure /—/. I could mix the dye stuff. Hand in hand with having to do my homework as hard as I could and somewhat pressured, but he was able to help me better with moderately scientific things up to the age of 12 or 13. After that he didn’t know things like calculus and things of that sort. From then onwards I would work mainly by myself.

I was interested in art and graphics. I think it’s important to me, the most important thing in my life, the thing I’m most keen on is art and graphic design and things of that nature. That went a little bit hand in hand, but I could never have got a job in that area. As I was quite good at sciences at the age of 18 I went to university to do maths, physics, and chemistry. Then to do chemistry as a degree. I wanted to do a PhD in state university because I was having such a good time. I played tennis a lot, actually, and I played for the university and I wanted to stay on and play more tennis and I was also involved with the university magazine doing their designs and covers. So I wanted to stay at the university. It seemed like a good place. It is a good place. And so I got a PhD in chemistry. Then I wanted to live abroad. It was very easy if you had a PhD in those days you could go and do a post doc and my supervisor, Richard Dixon, a professor at Bristol now, found a position for me in Ottawa as a post doc at the National Research Council which was headed by Gerhardt Hertzberg who had created a very effective and outstanding spectroscopy laboratory and I went there. And it was considered the Mecca of spectroscopy. You didn’t have to be any good. You must be good if you’d been there and survived. I spent two years there doing more spectroscopy and then I went to Bell Telephone for a year. Then I came back to England.

So your basic degree was in chemistry and then you specialised in spectroscopy after that?

Sir Harold Kroto: My best subjects at school were geography and art and then sciences. We weren’t encouraged to consider art as a possible career. We were encouraged to consider going to Oxford and Cambridge, to do Latin or something like that. I went to quite a good school. It was more easy in those days if you passed exams to go to certain schools. This school is now really more of a public school or what you call in the States a private school. I was able to go to this rather good school called Bolton School. I got a few little scholarships worth eight pounds a month or something like that to help. But I was good at chemistry, and gradually …

You realised chemistry would be your goal.

I don’t remember ever consciously thinking chemistry was the thing for me.

I don’t remember ever consciously thinking chemistry was the thing for me.Sir Harold Kroto: I don’t know how much I realised. It was easier for me. Maths and physics I was good at. Chemistry I don’t remember ever consciously thinking chemistry was the thing for me. I wanted to go to university and chemistry was the natural one for me to do. I had several very good chemistry teachers. One was a guy called Jerry who really was quite inspiring. But I had very good physics and maths teachers. Then the last year I had another teacher called Harry Heney who’s now a professor at Loughborough. He became a Professor, he left the school only after two years. He probably more than anybody else sent me on this, because he encouraged me to get Feazer and Feazer. An organic textbook to look at. So I got that for my birthday or something. Not many people get thick organic textbooks for their birthday but I got that. it’s a very good read. It reads well as well.

I’m not a chemist but I’ve seen this book. I know it’s famous.

Sir Harold Kroto: So I was good at organic chemistry at the time.

Microwave spectroscopy became your speciality at some point?

Sir Harold Kroto: Yes. What happened at university is … I was introduced to quantum mechanics and the experimental data that underpinned quantum mechanics is spectroscopy and I was in chemistry and I was taught spectroscopy by Richard Dixon as an undergraduate. And I somehow got quite fascinated by it. The fact that a molecule could count, you know there were regular series, beautiful patterns which I got interested in. Although I was very interested in organic chemistry at that time. I thought … When I wanted to do my PhD I’d like to do spectroscopy. I was in Sheffield where George Porter was, who got the Nobel Prize for flash photolysis, and so it was very exciting time because George had set up all this flash photolysis apparatus. There was that apparatus that belonged to him and Richard Dixon and I worked for Richard but I saw George all the time. He and Richard were quite influential in this.

I enjoyed it. I could play tennis and I could do graphics for the university magazine. I could play the guitar because in those days all the kids at university could play the guitar and sing in folk groups. I was having a good time. and then went to Ottawa to do more flash photolysis. Electronic spectroscopy. After one year in one lab I moved to work with Cec Costain, to do microwave spectroscopy, which is actually a lot simpler than the others. Electronic spectroscopy you have electronic motion, you have vibrational motio,n but in rotational you just have the rotation. So in a sense it’s simpler but more precise. And I was a chemist. So you could use microwave spectroscopy to study moderately complex molecules. I started to realise that it would allow me to do chemistry and identify the molecules and study them by what we call microwave spectroscopy.

I read here that in the mid 60s you went to the University of Sussex. Was that for your further academic career?

Sir Harold Kroto: Yes, because I went to do a post doc in Canada at the National Research Council for two years. 1964 to 66. In 67 I went to Bell Telephone for a year. My boss there, Johan Powell, then went to Case Western Reserve, and I had an offer of a post doctoral tutorial fellow. Slightly above a post doctoral fellowship at Sussex. When Johan left to go to Case I thought I’ll go back to Sussex. And that’s where I went and after half the year I was fortunately, or unfortunately, offered a permanent position there which I took. I spent five years trying to do something as a lecturer at Sussex and if it didn’t work I’d probably go and do night school and go into graphics and design. After five years things were starting to tick over. But I would say it took seven years to get really going which is a long time.

It takes a long time if you want to do something new.

Sir Harold Kroto: Well, absolutely, and in fact I think it’s tough on modern kids because they’re not left that length of time. I did one year as a post doc and then I was given a position which almost was impossible to throw me out. I had some degree of … sort of responsibility to do something. But at the same time I wasn’t under the pressure that young kids have to do something and if they don’t they get thrown out. I think in many cases, particularly in the USA, the tenure track appointment puts these kids under a lot of pressure which some respond well to and others probably don’t respond very well to.

The you also became interested in cosmochemistry. That means the chemistry in the space.

Sir Harold Kroto: In the space … I would call it interstellar chemistry. Cosmochemistry seems a bit more universal, so it’s more immediate than that. I think … because I was doing microwave spectroscopy or radio spectroscopy one was looking at the radio waves or the microwaves which molecules would absorb. And from that you can tell what they are. I mean in the same way as copper sulphate, the colour of copper sulphate is this rather distinctive blue and so once you’ve seen it you know that colour is copper sulphate. I mean there are very few other compounds so you can use that to determine it … use spectroscopy in the optical range to tell you what it is.

… I started to work on phosphorous chemistry which is the area of which I’m most proud as it turns out.

… I started to work on phosphorous chemistry which is the area of which I’m most proud as it turns out.In the same way, in the radio range you can use it to tell you what molecules you’ve got and you can tell whether you’ve got ethyl alcohol or ammonia or formaldehyde. And in 1967 or 68 Charles Townes, who invented the laser or maser or both if you wish, made another fantastic advance and he, together with his colleagues, detected water and ammonia in Orion. And this opened Pandora’s box because this meant that people in the microwave area could be quite helpful to astronomers using radio telescopes to detect molecules in the interstellar medium. And then in 1974 I started to work on phosphorous chemistry which is the area of which I’m most proud as it turns out. I’m most proud of my work on carbon phosphorous chemistry. But I was also working on carbon chains with a colleague, David Walton, who was an expert in making long carbon chain molecules, and an undergraduate. And we made a moderately long, really it was a short carbon chain, we were able to detect that by radio astronomy in the interstellar medium. And it turns out that in the space between the stars there’s huge massive gas clouds which are fairly low temperature but just warm enough so that the molecules can rotate. And as they rotate they give a radio wave and that radio wave you can detect.

Around the 1970s to 1975 there were tremendous advances in our understanding of the space between the stars being made. And we were a part of that, with a colleague Takeishi Oko, a fantastic Japanese scientist, now in Chicago, and astronomers in Canada. We were able to detect several carbon chain molecules and show that there were some interesting species. That was very exciting time. I mean the most exciting time scientifically was the period from 1974 to 1978. That four year period where my work in carbon phosphorous and carbon sulphur chemistry was really exciting. We’d go in and almost every week or month we’d have a new really quite significant result. In 1975, 1976 and 1977 we detected the carbon chain molecule. So that period was for me a golden period. I didn’t realise it was a golden period, but in retrospect it was a time of something special. I now look back at it. I can’t remember it very well.

Was it very hectic? You were busy all the time?

Sir Harold Kroto: Well, it wasn’t. It was hectic, but I had an idea that this would work. A student would have an idea. Results just seemed to pour out during that period in a way that they haven’t happened ever since.

But then we come to the question of the discovery of the fullerenes which must have been a very exciting discovery. It was also a short period …

Sir Harold Kroto: Absolutely. It follows on from the work that Takeishi and I and David Walton did earlier in the 70s in that the carbon chains were there and they presented a bit of a problem because they didn’t quite fit with the accepted theories of the way molecules were forming in the interstellar medium. And it seemed to me that they were actually produced in stars. Cool stars. Stars with high carbon content. And they were being blown into the interstellar medium. So there are stars which as they use up the hydrogen to form helium they then go onto a second phase where they use up the helium to form carbon. And at a certain stage they tend to explode and blow the carbon and other elements off into the interstellar medium. But they must be at moderately high pressure and temperature. And it seemed to me that there were going to be conditions in some of these stars, if not all of them, in which carbon chains would form. And therefore what we were seeing was the debris that had been blown out of the stars. That might or might not still be true. We don’t know. So I thought this was an interesting idea and I would go to conferences and suggest there’s a third way of making these. And in fact a star was detected which showed these things blowing out. But still no one was really paying any attention to it.

Then quite a long time after these discoveries, four years after the last of those in 1979, I was in Rice University and Rick Smalley had developed this fantastic apparatus in which you take a laser to vaporise graphite. Bob Curl whom I was visiting suggested that I go and see him because he’d got this beautiful result on silicon carbide and shown that silicon carbon, the carbon was a triangular molecule. And I thought that was really, really interesting. And as I was talking to Rick and watching him jumping over this fantastic apparatus, because he’s a very ebullient and forceful character, I thought maybe if we vaporise graphite we’ll produce the carbon chains. We’ll simulate the conditions in a carbon star. We’ll get a plasma which is similar to the plasma in the intermediate atmosphere of the star. That was a simple idea which could have been done almost on the spot. There were other ramifications… I suggested to Bob Curl and Bob Curl rang me up about 16 months later. It wasn’t an experiment that I was rushing around to do. It was an interesting experiment to me. It was less interesting to Rick. But Bob was pretty keen on one aspect of this experiment and I was keen on another, very simple … both aspects of it. And so in 1985 I got a phone call to go to Rice, either to go to Rice or in fact Shall we send you the results when we get them?

I wanted to do the experiment myself because I was fascinated …

I wanted to do the experiment myself because I was fascinated …I made a very important decision. I actually went to Rice University. I wanted to do the experiment myself because I was fascinated. It’s also worth pointing out that there’s a very good half price book store in Houston which is another reason for going. It wasn’t just that I wanted to do the science, I wanted to go to this bookstore. So I had two reasons to go. I think it’s important to be aware that I was pretty sure I knew what the answer to the question was going to be. People say there’s lots of philosophers of science which says you mustn’t do something where you know the answer to the question and in some sense that’s true. In this case I knew the answer to the question. I was absolutely certain that Rick Smalley’s apparatus would create these things. It’s tremendous advance technically because it was the first time you could vaporise refractory materials which are high temperature. It was a major technological advance in what we call cluster science. So I knew it. But even if you know the answer it’s probably a little bit of philosophy here. You ought to just check it out for several reasons.

The first reason is it might be true. Fine. Then you can tell, in my case, your colleagues who didn’t believe you. Ha, I told you so. You haven’t moved on further. You haven’t learned anything although you’ve learned that you’re right. But you’ve not actually made an advance in your own understanding of nature. You’ve just confirmed your knowledge. That’s useful because until you’ve got that confirmation you don’t know that you’re right. That’s important. The second thing about it is that it might go wrong and it doesn’t work and then you know that your other ideas were not right and that you’ve learned something now. You always learn more from an experiment that goes wrong than you do from an experiment that goes right. If it goes right according to your hypotheses.

So the second one if it goes wrong you’ve got to find out why it goes wrong. It may go wrong because you haven’t done it properly but it may also go wrong because your preconceptions and your received wisdom is incorrect. You definitely learn something in general there. And the third thing is it might go right but something totally unexpected might happen. Of course that’s what happened. In that experiment something happened that no one predicted. And in a sense the most important aspect of our discovery is not that this C60 football shaped molecule can be made. It’s that it makes itself spontaneously. Perhaps more important than anything else because that was a fundamental paradigm shift in our understanding of carbon. And also sheet materials. So lots of ramifications.

That is also a lesson that you were in a way, even if you didn’t expect anything unexpected, when you saw it you were wise enough to realise that it was something worth looking into and not just the noise in the electric current or something.

Sir Harold Kroto: Absolutely. Yes. That’s another aspect. Here was a result. You couldn’t miss it. Well, we couldn’t miss it but other people did. I think again the historical perspective and one important aspect is that the experiment would have been carried out twice before. I first suggested the experiment around Easter of 1984 and when I came back to Sussex at some stage, not that long after, maybe in the summer, Tony Stace, one of my colleagues, gave me a paper by a group at Exxon who had actually vaporised carbon. And it was a remarkable paper. They’d seen some very interesting new species. A whole set of carbon clusters from 30 to 190 maybe. And they were all even. And I looked at this paper and thought: Damn, we could have done this experiment. If only Bob and Rick had listened to me we could have done that the day I was there. It was a very, very easy experiment.

Anyway I read the paper through and there were some interesting aspects. Actually confirmed again more than ever before that the experiment that I wanted to do was perfectly feasible. In fact part of the experiment had been carried out in the sense that it had reacted the carbon clusters with sodium and they’d found that they were clusters which would take up two sodium atoms. And if you have a chain the sodium would go on the end so you’d expect a sodium at each end of this carbon chain so they’d seen something like NA C20 NA, and that seemed to me fit to be fit. But they had this other family of clusters between 30 and 190 and they were all even and they said it was something called carbine. Now I don’t believe in carbine actually. It doesn’t make any sense, chemical sense. It may be right.

What is carbine?

Sir Harold Kroto: Carbine. It’s supposed to be a solid made from polyines and whenever you try to condense polyines they blow up, so if carbine exists at all it can only exist for a very short time before it blows up and cross links to form a highly exothermic reaction in which things blow up. And I’ve seen these explosions anyway, so I had problems with it. But I thought they were graphite sheets. Sheets of graphite and you could rationalise that a sheet with an even number of atoms would be a little bit more stable than a sheet with an odd number of atoms. I looked at it but I didn’t pay a lot of attention to this. I thought that looks like what these things are. I think I should have been smarter than that. I feel I should have looked at that in more detail. Most of the experiment had been carried out. They hadn’t done the reactions with hydrogen and nitrogen that I’d wanted to do. There was another group at Bell Labs that also did the same experiment. In the Exxon work they had seen C60. But anyway the Bell Labs had seen C60 and picked it off. In our experiments we carried out some experiments which really changed the conditions. Really pushing this experiment. Not let’s do this in random and then rush to the next one. We found that the 60 signal could be made extremely strong. I’m sure if Exxon or Bell had persevered and changed the reaction conditions in the way that we did they would have seen the same results and they would have discovered C60. They would have said this thing is so strong, what structural explanation is there for this strong signal. And they didn’t do that. So I wouldn’t be sitting here being asked about it because they would have discovered it.

Can I round off by asking … Now it seems that there are coming some practical applications that you make materials out of …maybe not balls but at least tubes of this kind of materials. Do you have any ideas about this or would you say it’s more of the beauty of nature?

Sir Harold Kroto: I think there’s still some major problems to be solved. There is no doubt that the round cages are beautiful and they’ve changed our understanding of graphite and how graphite behaves, that it can close up into a cage. The nanotubes which were discovered by Japanese Sumio Igima. They’re very interesting. They’re elongated cages. They bear the same relationship to a dome or a ball as a tube does to these so called nanotubes. They’re fascinating. They can conduct like metals you know inorganic super conductor. They’re extremely strong. Probably the strongest materials ever made. But to actually use those properties is a major problem which has yet to be solved. And maybe quite difficult. I’m a bit apprehensive that the applications of nanotubes and C60 will be in the near future still have big technological problems. There’s always the hint of exciting promise. Getting that promise to the marketplace is another matter.

That is of course something else. Thank you very much.

Sir Harold Kroto: My pleasure.

Thank you very much.

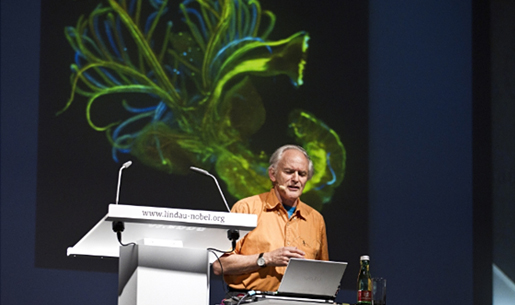

Interview with Sir Harold Kroto by Astrid Gräslund at the meeting of Nobel Laureates in Lindau, Germany, June 2000.

Sir Harold Kroto talks about his family background and education; his interest in spectroscopy research (8:19); his first position at Sussex University (10:37); interstellar chemistry (12:50); the discovery of fullerenes (17:06); and potential future applications of his discovery (27:52).

Did you find any typos in this text? We would appreciate your assistance in identifying any errors and to let us know. Thank you for taking the time to report the errors by sending us an e-mail.

Sir Harold Kroto – Other resources

Links to other sites

Harry Kroto – personal legacy from University of Sheffield

Obituary from The Royal Society

The Kroto Lectures from The Vega Science Trust

About Harry Kroto from Kroto Research Institute

‘Richard E. Smalley, Robert F. Curl, Jr., and Harold W. Kroto’ from Chemical Heritage Foundation

On Sir Harold W. Kroto from Lindau Mediatheque

Robert F. Curl Jr.- Banquet speech

Robert F. Curl Jr.’s speech at the Nobel Banquet, December 10, 1996

Your Majesties, Ladies and Gentlemen,

Harold Kroto, Richard Smalley and I are deeply grateful for the honors you have given us today. The Nobel Prize is the ultimate celebration of scientific discovery. We are delighted that our contribution in the discovery of the carbon cage molecules that we called the fullerenes is being recognized. I have to make clear that we do not and cannot claim this discovery is ours alone. Two people who are equally responsible, Professor James Heath and Dr. Sean O’Brien, are in this room tonight. There are several others who made important contributions to the fullerene research and deserve to be recognized, most notably Dr. Yuan Lin and Dr. Qing-Ling Zhang, and Professor Frank Tittel. Professor Tittel is also here tonight.

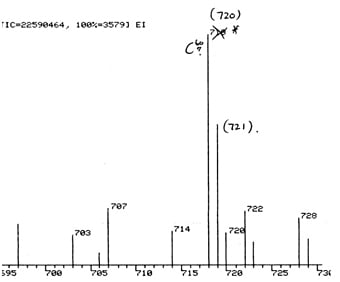

None of us has recovered, or are ever likely to recover, from our astonishment that these beautiful three dimensional molecules are formed spontaneously when carbon vapor condenses under the right conditions, and that we were fortunate enough to discover this amazing fact. This discovery grew out of the union of Richard Smalley’s and my studies of clusters and the apparatus Richard Smalley developed for this purpose with Harold Kroto’s interest in carbon in the interstellar medium. At the outset, none of us had ever imagined these carbon cage molecules. When we looked at carbon, the single astounding carbon sixty peak in the mass spectrum and the circumstances under which it came to prominence admitted no other explanation than the totally symmetric spherical structure, and suddenly a door opened into a new world.

The fullerenes have caused chemists to realize the amazing variety of structures elemental carbon can form from the well-known three-dimensional network that is diamond and the equally well-known flat sheets of hexagonal rings that are graphite to the newer discoveries of the three-dimensional cages that are fullerenes. We have learned that the cages can be extended into perfect nanoscale tubules which offer the promise of electrically conducting cables many times stronger than steel. Or the cages can nestle one inside the other like Russian dolls. Now that we have become more aware of the marvelous flexibility of carbon as a building block chemists may ultimately learn how to place five- and seven-membered rings precisely into a network of hexagonal rings so as to create nano structures of ordered three-dimensional complexity like the interconnecting girders in a steel-frame building.

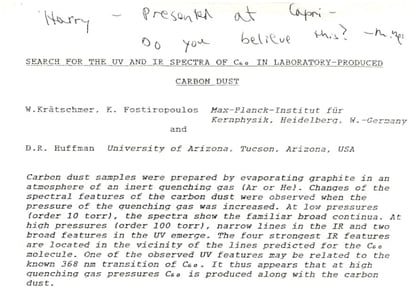

At this moment there is no commercial product based upon fullerenes, but it is only eleven years since we found they form spontaneously and only six years since Wolfgang Krätschmer and Donald Huffman and their students put these unique compounds into the hands of chemists. We are confident that uses will come probably in materials science with fullerenes as parts of composites and perhaps in medicine. Many scientists around the globe are exploring their unique properties. Perhaps soon one of these groups will make a discovery of a significant use for fullerenes or find a clever way to control the morphology of carbon.

Speaking for Harold Kroto and Richard Smalley, we thank you for the wonderful honors you have bestowed upon us today.

Robert F. Curl Jr.- Nobel Lecture

Nobel Lecture, December 7, 1996

Dawn of the Fullerenes: Experiment and Conjecture

Read the Nobel Lecture

Pdf 992 kB

Robert F. Curl Jr.- Interview

Interview with Professor Robert F. Curl Jr. by freelance journalist Marika Griehsel at the 55th meeting of Nobel Laureates in Lindau, Germany, June 2005.

Professor Curl talks about his interest in chemistry as a child; the work for which he was awarded the Nobel Prize (2:31); problems with patenting discoveries (7:20); memories from the Nobel Week (8:59); and his working life after the Nobel Prize (12:54).

Interview transcript

Thank you Professor for coming to this interview with us. Professor Curl, I believe I read something about you, that you got your first chemistry box when you were quite a small child?

Robert F. Curl Jr.: That’s right.

Was that how it all started?

Robert F. Curl Jr.: Yes, it really is, I got this chemistry set I think it was for Christmas it’s a little hard to remember for sure. I had a little room over the garage that I could play with it in and essentially what I did was all of the little experiments that they suggested in the booklet that came with it and I hadn’t exhausted possibility for mixing up chemicals so I tried mixing every possible combination to see what happened. And I became fascinated with chemistry and decided essentially then to become a chemist.

You didn’t scare your parents, did anything that sort of upset them?

Robert F. Curl Jr.: I did upset my mother on one occasion, this was much later when I was in high school, I was doing some experiment on her stove and boiled over some nitric acid and ate the enamel off the stove and did bother her quite a bit. In fact, she talked about it for years.

Is that something, if you have children in your family or grandchildren or so on, do you encourage that kind of you know experimenting and being so curious?

Robert F. Curl Jr.: I encouraged … I’m beginning to despair because neither one of my two sons who have gone on to be quite, you know, they’re adults and actually middle aged now and been quite successful, are not at all interested in that sort of thing. I would buy a little kit to do electronics or something and they would not be very interested doing any of the little experiments.

Not even after you got a Nobel Prize?

Robert F. Curl Jr.: They were of course adult by that time. My grandchildren have not been particularly interested so far. I have one yet coming that’s not yet five that may turn out to might be interested in doing something but no, it hadn’t happened.

Did you think that there was a possibility for you to get the prize when you discovered what you discovered together with your colleagues and put them together and started to work together?

Robert F. Curl Jr.: No, I always have judged the interest in things on the attitude of organic chemists. They’re, in the United States at least, the organic chemists are the ones who create the atmosphere for chemistry. And they … I remember in the years following doing this experiment that I would go and give a talk about the work that we had done on carbonate some place and I’d give this talk and people would be interested. They would inevitably at the end of the talk, there would be some organic chemists who would raise his hand and say can I see a sample of this material? And then I would have to explain that no we were only talking about a few thousands molecules in a big machine and that we’ve never actually seen a large sample and they would immediately lose interest.

… I couldn’t conceive that there would be a prize if the organic chemists were not interested in it …

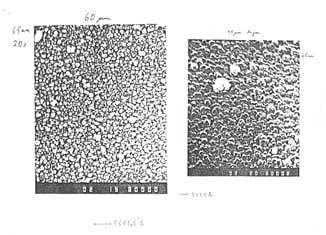

… I couldn’t conceive that there would be a prize if the organic chemists were not interested in it …And so I couldn’t conceive that there would be a prize if the organic chemists were not interested in it. And what changed things was the work of Wolfgang Krätschmer and Donald Huffman who made and developed a method for making microscopic samples of these materials. Then the organic chemists could get their hands on it and it was at that point that I thought there might be a prize for either them or us.

And it was you. But you say also that it was not just you and your two colleagues who had worked together on this.

Robert F. Curl Jr.: No, there were actually a number of graduate students, at least three who were involved, you know, in the very initial work. The two that get most of the credit, that we brought to Stockholm, and who were on the original paper, Sean O’Brian and Jim Heath, were, you know, certainly they have … and we’ve acknowledged and very much /- – -/ their contributions. There was another graduate student Yuan Liu who’s not really gotten the credit that she deserves. What happened was that she was married and her husband lived in San Francisco and she was a graduate student in Houston and just at the time that the most crucial experiments were being done she had a long schedule trip to go visit her husband and so she was not there when these crucial experiments were done and when the paper was written. But she was actually involved from the very beginning and then I had a student Qing-Ling Zhang who was around but really got involved with this little after the beginning.

So I suppose that’s how it goes in these fields, that you have … either you can be sort of secretive about it and just work very lonely or you include lots of people and of course then you know you might not all be mentioned when the prize is given.

Robert F. Curl Jr.: The prize is limited to three individuals so that’s a difficulty because there are many more people than three individuals that contribute. Science is a very social occupation. The image of the scientist is the mad fantasist who lives on top of a mountain top and only has his faithful servant Igor to help him is a complete myth. Has nothing to do with the way science is actually done. In fact, I claim that the people who really work in solitary are the humanists, they go to the library and closes themselves with the books and sit there and try to write their books and their papers and have far less human contact than the daily activities of their profession than scientists do.

I was thinking now and when patent is becoming or has been but is becoming more and more important and sometimes it also become a big quarrel between the scientist and maybe the university or the company that you’re working for, when you do your major discovery, how can one get around that or has it badly influenced the social aspect of research do you think?

Robert F. Curl Jr.: I don’t know that it in terms of academic research I don’t know that it has. For one thing, certainly in the past, most university professors were not working in things that were immediately patentable. That’s changing, people are more interested in doing things that are of practical importance. In my university, occasionally we get into an interesting paradox because by university regulation the PhD final oral examination is public, it has to be publicly announced and anyone can come and for some of us, some of the professors who are working with very commercially interesting things they find themselves in a really serious bind.

When you went to Stockholm to receive the prize is there any memories from that …

Robert F. Curl Jr.: It’s sort of a blur. It’s a very active week, it tends to go by almost in a blur. I remember lots and lots of pleasant things, everybody was extremely nice, it was wonderful to be the centre of attention and simultaneously exhausting. The things that I remember most vividly were when I gave a talk about the work, okay, and I remember being relaxed even though this was being televised, and feeling very … quite comfortable with giving an hour long talk that was being televised to thousands of people at least.

… I became increasingly nervous, in spite of the fact that I had very little to actually do …

… I became increasingly nervous, in spite of the fact that I had very little to actually do …Then when they had the ceremony and I was supposed to go up and receive the prize from the King, before that happened, this is maybe an old familiar story, but before that happened I became increasingly nervous, in spite of the fact that I had very little to actually do. And almost nothing to say except thank you. You know I recall being extremely nervous in that regard and managed to get through it. I don’t know the origins of such nervousness, whether it I was going to drop it or I would fall down on the way or whatever.

So that was one memory and the other memory I had was that there was a television programme that was moderated by Jonathan Mann who’s at CNN, and I was sitting there, with all the lawyers sitting there, and the conversation was sort of bouncing around and it hadn’t bounced toward me and I hadn’t felt motivated to say much so I was sort of sitting there like dumb frankly. And with out of the blue without any indication this was going to happen Jonathan Mann turns to me and says “What do you think will be the most significant developments in your field over the next 20 years?” And the response that over the course of time became obvious to me is that, would be me say “Well, how would I know!” They wouldn’t miss if I knew. But anyway I really fumbled a response to that question yea and that sort of haunted me for a quite a while after it was over, but …

You did say after having received this award that people ask you all sorts of questions and you sort of supposed to know all the answers to it, all different issues and what goes on with humankind?

Robert F. Curl Jr.: You get used to saying I don’t know. I hated that because you know you’re trained to avoid ignorance to try to know things and so to constantly have to say I don’t know is, you know, it’s hard, it takes a while to get used to that.

It’s very honest though isn’t it to be able to say that.

Robert F. Curl Jr.: It’s certainly superior than making something up.

Has it changed your working life though, this award?

Robert F. Curl Jr.: Yes, it changed it both positive and negative ways. The positive way has been that it’s been easier to get money and co-workers I think. The negative way is that you get a lot of e-mails of course not a whole lot but enough to be significant of email correspondence about things that you would really not particularly want get involved with. Things like getting messages from students.

There are two kinds of messages from students, the one kind is the one where the student really seems to be genuinely interested and has some question that shows that they’ve actually thought about something and then there’s the student who has a homework assignment and feels that this would be a good way to get help on their assignment. And so the first kind I enjoy, the second kind you know I don’t want to feel caught on a crux because you don’t want to discourage any serious student, but you don’t see how it actually helps their development for you to supply them with answers to their assignment, so.

Any specific … do you think that scientists of your calibre, those who have received the award from the Nobel Foundation, have any specific responsibilities?

Robert F. Curl Jr.: I don’t think we have any more responsibility than the average citizen has, we don’t, you know, we haven’t become brilliant overnight. Getting the Nobel Prize did not increase our intelligence, let’s put it that way. And it certainly didn’t make us experts in all areas. So, it does give you a certain ability to get people to listen. And so, therefore you have a responsibility as any citizen would have if you feel that there is something you have to say that people really need to listen to, then you should definitely go ahead and say it and try to do what you can to either improve things or try and help overt disaster.

Thank you very much Professor, I really enjoyed this. Thank you.

Did you find any typos in this text? We would appreciate your assistance in identifying any errors and to let us know. Thank you for taking the time to report the errors by sending us an e-mail.

Sir Harold Kroto – Facts

Sir Harold Kroto – Biographical

I was the kid with the funny name in my form. That is one of the earliest memories I have of school (except for being forced to finish school dinners). Other kids had typical Lancashire names such as Chadderton, Entwistle, Fairhurst, Higginbottom, Mottershead and Thistlethwaite though I must admit that there were the odd Smith, Jones and Brown. My name at that time was Krotoschiner (my father changed it to Kroto in 1955 so it is now occasionally thought, by some, to be Japanese). I felt as though I must have come from outer space – or maybe they did! I now realise that I had made a continual subconscious effort to blend as best I could into the environment by making my behaviour as identical as possible to that of the other kids. This was not easy indeed it was almost impossible with a couple of somewhat eccentric parents (in particular an extrovertly gregarious mother) who were born in Berlin and came to Britain as refugees in their late 30’s.

Bolton is a once prosperous but then (the fifties) decaying northern English town which is rightfully proud of its legendary contributions to the industrial revolution – the likes of Samuel Crompton and Richard Arkwright were Boltonians. Indeed we lived in Arkwright St. and I shall always remember walking to school each morning past the windows of cotton mills through which I could see the vast rows of massive looms and spinning frames operated by women who had been working from at least six o’clock in the morning, if not earlier.

My efforts to merge into the background meant, among other things such as fighting (literally) for survival, speaking only English (all real Englishmen expect others to speak English) – though I allowed myself to absorb just enough German to understand what my parents were saying about me when they spoke German. One specific memory was that when I did particularly poorly at French one year my Father gave me a very large French dictionary for my birthday – was I pleased!!!

My name seems to have its origins in Silesia where my father’s family originated and there is a town in Poland now called Krotoszyn (then Krotoschin). My father’s family came from Bojanowo and set up a shop in Berlin where my father was born in 1900. The original family house, which was then a shop, still exists in the main square in Bojanowo. I have an old photograph which shows the sign “I. Krotoschiner” in gothic characters emblazened over the window. I visited the town recently and, apart from cars rather than horsedrawn carts and the sign, little has changed – the Hotel Centralny is now the Restauracja Centralny and the aerials on the roofs are still there!

My father, who originally wanted to be a dress designer but somehow ended up running a small business printing faces and other images on toy balloons, had to leave Berlin in 1937 and my mother (who was not Jewish) followed a few months later. I always felt that my parents had a really raw deal, as did almost everyone born in Europe at the turn of the Century. The First World War took place while they were teenagers, then the Depression struck and Hitler came to power while they were young adults. They had to leave their home country and then the Second World War broke out and they had to leave their home again. When my father was 45 he had to find a new profession, when he was 55 he set up his business again and when he was 65 he realised I was not going to take it over. He sold the business and retired in his early 70’s.

I do not know how my father managed to catch the train to take him over the border into Holland in 1937. For as long as I knew him he was always late for everything; he invariably missed every train or bus he was supposed to catch. He told me that this was because he was called up in 1917 to go to the Front but arrived at the station just as the train was pulling out. When he asked the station master what he should do, he was told to go home. From then on he decided to make a point of missing trains and buses, but seems to have made one exception, in 1937. My parents managed to set up their small business again in London but the effort was, of course, short lived due to the outbreak of the War in September 1939. I was born in Wisbech (a very small town in Cambridgeshire to which my mother was evacuated) on Oct 7th 1939 in the first month of the War so I was a war baby. My father was interned on the Isle of Man because he was considered to be an enemy alien; my mother (who was also an alien, but presumably assumed not to be an enemy one) was moved (with me – when I was about one year old) from London to Bolton in 1940. After the war my father became an apprentice engineer and because he was so good with his hands he managed to get a job as a fully qualified toolmaker at an engineering company in months rather than years.

In 1955, with help from friends in England and Germany from before the war, he set up his own small factory again, this time to make balloons as well as print them. I spent much of my school holidays working at the factory. I was called upon to fill in everywhere, from mixing latex dyes to repairing the machinery and replacing workers on the production line. I only now realise what an outstanding training ground this had been for the development of the problem solving skills needed by a research scientist. I am also sure that what I was doing then would contravene present-day health and safety at work regulations. I would have been considered too young and inexperienced to do the sort of maintenance work that I was often called upon to do. I did the stocktaking twice-a-year using a set of old scales with sets of individual gram weights (weighing balloons 10 at-a-time to obtain their average weights), my head, log tables and a slide rule to determine total numbers of various types of balloons. No paradise of microprocessor controlled balances then. After each stocktaking session I invariably felt that I never wanted to see another balloon as long as I lived.

My parents had lost almost everything and we lived in a very poor part of Bolton. However they did everything they could to get me the best education they could. As far as they were concerned this meant getting me into Bolton School, a school with exceptional facilities and teachers. As a consequence of misguided politically motivated educational policies this school has become an independent school and it bothers me that, were I today in the same financial position as my parents had been when I was a child, I would not be able to send my children to this school. Though I did not like exams or homework anymore than other kids, I did like school and spent as much time as I could there. At first I particularly enjoyed art, geography, gymnastics and woodwork. At home I spent much of the time by myself in a large front room which was my private world. As time went by it filled up with junk and in particular I had a Meccano set with which I “played” endlessly. Meccano which was invented by Frank Hornby around 1900, is called Erector Set in the US. New toys (mainly Lego) have led to the extinction of Meccano and this has been a major disaster as far as the education of our young engineers and scientists is concerned. Lego is a technically trivial plaything and kids love it partly because it is so simple and partly because it is seductively coloured. However it is only a toy, whereas Meccano is a real engineering kit and it teaches one skill which I consider to be the most important that anyone can acquire: This is the sensitive touch needed to thread a nut on a bolt and tighten them with a screwdriver and spanner just enough that they stay locked, but not so tightly that the thread is stripped or they cannot be unscrewed. On those occasions (usually during a party at your house) when the handbasin tap is closed so tightly that you cannot turn it back on, you know the last person to use the washroom never had a Meccano set.

At no point do I ever remember taking religion very seriously or even feeling that the biblical stories were any different from fairy stories. Certainly none of it made any sense. By comparison the world in which I lived, though I might not always understand it in all aspects, always made a lot of sense. Nor did it make much sense that my friends were having a good time in a coffee bar on Saturday mornings while I was in schul singing in a language I could not understand. Once while my father and I were fasting, I remember my mother having some warm croissants – and did they smell good! I decided to have one too – ostensibly a heinous crime. I waited for a 10 ton “Monty Python” weight to fall on my head! It didn’t. Some would see this lack of retribution as proof of a merciful God (or that I was not really Jewish because my mother wasn’t), but I drew the logical (Occam’s razor) conclusion that there was “nothing” there. There are serious problems confronting society and a “humanitarian” God would not have allowed the unaccountable atrocities carried out in the name of any philosophy, religious or otherwise, to happen to anyone let alone to his/her/its chosen people. The desperate need we have for such organisations as Amnesty International has become, for me, one of the pieces of incontrovertible evidence that no divine (mystical) creator (other than the simple Laws of Nature) exists.

The illogical excuses, involving concepts such as free will(!), convoluted into confusing arguments by clerics and other self-appointed guardians of universal morality, have always seemed to me to be just so much fancy (or actually clumsy) footwork devised to explain why the fascinating and beautifully elegant world I live in operates exactly the way one would expect it to in the absence of a mystical power. Of course the excuses have been honed and polished over millennia to retain a hold over those unwilling or unable to accept that, as a Croatian friend of mine once neatly put it, “When you’ve had it you’ve had it”.

The humanitarian philosophies that have been developed (sometimes under some religious banner and invariably in the face of religious opposition) are human inventions, as the name implies – and our species deserves the credit. I am a devout atheist – nothing else makes any sense to me and I must admit to being bewildered by those, who in the face of what appears so obvious, still believe in a mystical creator. However I can see that the promise of infinite immortality is a more palatable proposition than the absolute certainty of finite mortality which those of us who are subject to free thought (as opposed to free will) have to look forward to and many may not have the strength of character to accept it.

[After all this, I have ended up a supporter of ideologies which advocate the right of the individual to speak, think and write in freedom and safety (surely the bedrock of a civilised society). I have very serious personal problems when confronted by individuals, organisations and regimes which do not accept that these freedoms are fundamental human rights. I feel one must oppose those who claim that the “good” of the community must come before that of the individual – this claim is invariably used to justify oppression by the state. Furthermore there has never been any consensus on what the “good” of the community actually consists of, whereas for individuals there is little difficulty. Thus I am a supporter of Amnesty International, a humanist and an atheist. I believe in a secular, democratic society in which women and men have total equality, and individuals can pursue their lives as they wish, free of constraints – religious or otherwise. I feel that the difficult ethical and social problems which invariably arise must be solved, as best they can, by discussion and am opposed to the crude simplistic application of dogmatic rules invented in past millennia and ascribed to a plethora of mystical creators – or the latest invention; a single creator masquerading under a plethora of pseudonyms. Organisations which seek political influence by co-ordinated effort disturb me and thus I believe religious and related pressure groups which operate in this way are acting antidemocratically and should play no part in politics. I also have problems with those who preach racist and related ideologies which seem almost indistinguishable from nationalism, patriotism and religious conviction.]

My art teacher, Mr Higginson, would give me special tuition at lunch times or after school was over. My father made me finish all my homework and I had to stay up until it was not only complete but passed his inspection – midnight if necessary. As time progressed, for reasons which I am not sure I understand, I gravitated towards chemistry, physics and maths (in that order) and these became my specialist subjects in the 6th form. I was keen on sport, and in school I concentrated on gymnastics whilst outside school I played as much tennis as I could. I patterned my backhand (and my haircut) on that of Dick Savitt and my service on that of Neil Fraser. At one time I remember wanting to be Wimbledon champion but decided that this goal was going to be a bit hard to achieve as I seemed to be having too much difficulty winning.

I started to develop an unhealthy interest in chemistry during enjoyable lessons with Dr. Wilf Jary who fascinated me most with his ability, when using a gas blowpipe to melt lead, to blow continuously without apparently stopping to breath in. I, like almost all chemists I know, was also attracted by the smells and bangs that endowed chemistry with that slight but charismatic element of danger which is now banned from the classroom. I agree with those of us who feel that the wimpish chemistry training that schools are now forced to adopt is one possible reason that chemistry is no longer attracting as many talented and adventurous youngsters as it once did. If the decline in hands-on science education is not redressed, I doubt that we shall survive the 21st century. I became ever more fascinated by chemistry – particularly organic chemistry – and was encouraged by the sixth form chemistry teacher (Harry Heaney, now Professor at Loughborough) to go to. Sheffield University because he reckoned it had, at the time, the best chemistry department in the UK (and perhaps anywhere) – a friendly interview with the amazing Tommy Stephens (compared with a most forbidding experience at Nottingham) settled it.

I was born during the war so I just escaped military service. As all the normal places at Oxbridge were already assigned for the next two years to reemerging national servicemen, I needed to achieve scholarship level to get to Cambridge. This turned out to be a bit difficult as I had been assigned a college with an examination syllabus orthogonal to the one that I had studied. Ian McKellen, the actor, who was in the same year at school, only seems to have needed to remember his lines from his part as Henry V in the school play!

The first day that I arrived in Sheffield, I walked past a building which had a nameplate saying it was the Department of Architecture and was bemused – did people do that at University? I had somehow missed this possibility because general careers advice was non-existent at that time. With hindsight I am sure that with the advice available today I would have done something like architecture which would have conflated my art and technology interests. At Sheffield I did as much as I could. Initially I lived with a family in Hillsborough, near to the Sheffield Wednesday football ground and occasionally watched them – very occasionally as I am a Bolton Wanderers supporter. I played as much tennis as I could which helped to get me a room in a hall of residence (Crewe Hall). I played for the university tennis team and we got to the UAU (Universities Athletics Union) final twice – the team would probably have been champions without me – which they were in 1964. I wanted to continue with some form of art, which was really my passion, and became art editor of “Arrows” (the student magazine which we published each term), specialising in designing the magazine’s covers and the screenprinted advertising posters. Whilst a research student I won a Sunday Times bookjacket design competition – the first important (national) prize I was to get for a very long time. Later my cover design for the departmental teaching and research brochure “Chemistry at Sussex” was featured in “Modern Publicity” (an international annual of the best in professional graphic design) – I consider this to be one of my best publications.

In the 1960s almost everybody could play the guitar well enough to play and sing two or three songs at a party so I had a go at that too and learned just enough chords (about half-a-dozen) to play some simple songs at local student folk clubs. I also decided that I should do some administration in the Students’ Union and from secretary of the tennis team I somehow ended up as President of the Athletics Council. During my last year at University (1963-64) I spent some 2-3 hours of each day attending to administration in the sports office in the Union. That year’s involvement in embryonic politics was enough to last a lifetime. I managed to do enough chemistry in between the tennis, some snooker and football, designing covers and posters for “Arrows”, painting murals as backdrops for balls and trying to play the guitar, to get a first class honours BSc degree (1958-61) and a PhD (1961-64) as well as some job offers. I also got married.

I had been keen on organic chemistry when I arrived at Sussex (at the behest of Harry Heaney I had bought Fieser and Fieser’s Organic Chemistry and read much of it while at school – it was a good read), but as the university course progressed I started to get interested in quantum mechanics and when I was introduced to spectroscopy (by Richard Dixon, who was to become Professor at Bristol) I was hooked. It was fascinating to see spectroscopic band patterns which showed that molecules could count. I had a problem as I really liked organic chemistry (I guess I really liked drawing hexagons) but in the end I decided to do a PhD in the Spectroscopy of Free Radicals produced by Flash Photolysis – with Richard Dixon. George Porter was Professor of Physical Chemistry at that time so there was a lot of flashing going on at Sheffield.

In 1964 I had several job offers but Marg(aret) and I decided that we wanted to live abroad for a while and Richard Dixon had inveigled an attractive offer of a postdoctoral position for me from Don Ramsay at the National Research Council in Ottawa. In 1964 Marg and I left Liverpool, on the Empress of Canada, for Montreal and then went on to Ottawa by train. I arrived at the famous No. 100, Sussex Drive, NRC, Ottawa, where Gerhard Herzberg (GH) had created the mecca of spectroscopy with his colleagues Alec Douglas, Cec Costain, Don Ramsay, Boris Stoicheff and others. At the time NRC was the only national research facility worldwide that was recognised as a genuine success. I suspect that this was because the legendary Steacie had left researchers to do the science they wanted; now unfortunately – as almost everywhere else – administrators decide what should be done. I remember easily making friends with all the other postdocs who congregated each morning and afternoon in the historical room 1057 – the spectroscopy tea/coffee area. The atmosphere was, in retrospect, quite exhilarating and many there, including: Reg Colin, Cec Costain, Fokke Creutzberg, Alec Douglas, Werner Goetz, Jon Hougen, Takeshi Oka and Jim Watson and their families became our lifelong close friends. As I look back I realise that Cec Costain, Jon Hougen, Takeshi Oka and Jim Watson were to exert enormous direct and indirect influence on my scientific development. I gradually learned to recognise who was good at what and what (if anything) I was good at. To paraphrase Clint Eastwood “A (scientist’s) gotta know his limitations”- and in this somewhat daunting company I learned mine. Although I knew that my level of knowledge and understanding was limited when I arrived, I was never made to feel inferior. This encouraging atmosphere was, in my opinion, the most important quality of the laboratory and permeated down directly from GH, Alec and Cec – it was a fantastic, free environment. The philosophy seemed to be to make state-of-the-art equipment available and let budding young scientists loose to do almost whatever they wanted. Present research funding policies appear to me to be opposed to this type of intellectual environment. I have severe doubts about policies (in the UK and elsewhere) which concentrate on “relevance” and fund only those with foresight when it is obvious that many (including me) haven’t got much. There are as many ways to do science as there are scientists and thus when funds are scarce good scientists have to be supported even if they do not know where their studies are leading. Though it seems obvious (at least to me) that unexpected discoveries must be intrinsically more important than predictable (applied) advances it is now more difficult than ever before to obtain support for more non-strategic research.

In 1965 after a further year of flash photolysis/spectroscopy in Don Ramsay’s laboratory, where I discovered a singlet-singlet electronic transition of the NCN radical and worked on pyridine which turned out to have a nonplanar excited state (still to be fully published!), I transferred to Cec Costain’s laboratory because I had developed a fascination for microwave spectroscopy. There I worked on the rotational spectrum of NCN3. Sometimes Takeshi Oka would be on the next spectrometer-working next to someone with such an exceptional blend of theoretical and experimental expertise did not help to alleviate the occasional sense of inadequacy. I really learned quantum mechanics (as did we all) from an intensive course that Jon Hougen gave at Carleton University. Whenever I was in difficulty theoretically (which was most of the time) Jim Watson helped me out – when he was not busy helping everyone else out. Gradually I realised that many in the field were stronger at physics than chemistry and in retrospect I subconsciously recognised that there might be a niche for me in spectroscopy research if I could exploit my relatively strong chemistry background.

In 1966, after two years at NRC, John Murrell (who had taught me quantum chemistry at Sheffield) offered me a postdoctoral position at Sussex. We were quite keen to live in the US, however, and I managed to get a postdoctoral position at Bell Labs (Murray Hill) with Yoh Han Pao (later Professor at Case Western) to carry out studies of liquid phase interactions by laser Raman spectroscopy. David Santry (now Professor at McMaster) was also working with Yoh Han at that time and each evening Dave and I carried out CNDO theoretical calculations on the electronic transitions of small molecules and radicals. I learned programming (Fortran) from Dave who threw me in at the deep end by showing me how to modify and correct the programs and then left me to see if I could do it myself.

During the year I received another letter from John Murrell to say that the position that had been available at Sussex the previous year was still available but would not be so for much longer. Thus Marg, Stephen (who had been born in Ottawa) and I came back to the UK- my annual salary dropped from $14000 to 1400 pounds, ouch! Marg had to find part-time employment as soon as possible although pregnant with our second son, David (we were poorer – but we were happier …. ! ! ! ). I was just about to start writing off for some positions back in the US and had just located the address of Buckminster Fuller’s research group (I was interested in the way that predesigned urban sub-structures might be welded into an efficient large urban complex) when John Murrell offered me a permanent lectureship at Sussex which I accepted.

I remember thinking I would give myself five years to make a go of research and teaching and if it was not working out I would re-train to do graphic design (my first love) or go into scientific educational TV (I had had an interview with the BBC before we went to Canada). I started to build up a microwave laboratory to probe unstable molecules and Michael Lappert encouraged me to use his photoelectron spectrometer to carry out work independently.

By 1970 I had carried out research in the electronic spectroscopy of gas phase free radicals and rotational microwave spectroscopy, I had built He-Ne and argon ion lasers to study intermolecular interactions in liquids, carried out theoretical calculations and learned to write programs. At Sussex I carried on liquid phase Raman studies, rebuilt a flash photolysis machine and built a microwave spectrometer and started to do photoelectron spectroscopy. I had applied for a Hewlett Packard microwave spectrometer and SERC, in its infinite wisdom, decided to place the equipment at Reading (where my co-applicant, a theoretician (!), worked) so requiring me and my group (the experimentalists) to travel each month to Reading to make our measurements! However by 1974, after three further attempts to get my own spectrometer (with help in consolidating my proposal from David Whiffen), the SERC finally gave in and I got one of my own at Sussex. The first molecule we studied was the carbon chain species HC5N – to which the start of my role in the discovery of C60 can be traced directly.

The discovery of C60 in 1985 caused me to shelve my dream of setting up a studio specialising in scientific graphic design (I had been doing graphics semiprofessionally for years and it was clear that the computer was starting to develop real potential as an artistically creative device). That was the downside of our discovery. I decided to probe the consequences of the C60 concept. In 1990 when the material was finally extracted by Krätschmer, Lamb, Fostiropoulos and Huffman, I and my colleagues Roger Taylor and David Walton, decided to exploit the synthetic chemistry and materials science implications. I began to realise that I might never fulfill my graphics aspirations. In 1991 I was fortunate enough to be awarded a Royal Society Research Professorship which enables me to concentrate on research by allowing me to do essentially no teaching. However I like teaching so I continue to do some. I have discovered that since I stopped teaching 1st and 2nd-year students, home-grown graduate students are few and far between.

In 1995, together with Patrick Reams a BBC producer, I inaugurated the Vega Science Trust to create science films of sufficiently high quality for network television broadcast (BBC2 and BBC Prime). Our films not only reflect the excitement of scientific discovery but also the intrinsic concepts and principles without which fundamental understanding is impossible. The Trust also seeks to preserve our scientific cultural heritage by recording scientists who have not only made outstanding contributions but also are outstanding communicators. The trust, whose activities are coordinated by Gill Watson, has now made some 20 films of Royal Institution (London) Discourses archival programmes and interviews.

I have been asked many questions about our Nobel Prize and have many conflicting thoughts about it. I have particular regrets about the fact that the contributions of our student co-workers Jim Heath, and Sean O’Brien as well as Yuan Liu receive such disparate recognition relative to that accorded to ours (e.g. Bob, Rick and me). I also have regrets with regard to the general recognition accorded to the amazing breakthrough that Wolfgang Krätschmer and Don Huffman made with their students Kostas Fostiropoulos and Lowell Lamb in extracting C60 using the carbon arc technique and which did so much to ignite the explosive growth of Fullerene Science. I have heard some scientists say that young scientists need prizes such as the Nobel Prize as an incentive. Maybe some do, but I don’t. I never dreamed of winning the Nobel Prize – indeed I was very happy with my scientific work prior to the discovery of C60 in 1985. The creation of the first molecules with carbon/phosphorus double bonds and the discovery of the carbon chains in space seemed (to me) like nice contributions and even if I did not do anything else as significant I would have felt quite successful as a scientist. A youngster recently asked what advice I would give to a child who wanted to be where I am now. One thing I would not advise is to do science with the aim of winning any prizes let alone the Nobel Prize that seems like a recipe for eventual disillusionment for a lot of people. [Over the years I have given many lectures for public understanding of science and some of my greatest satisfaction has come in conversations with school children, teachers, lay people, retired research workers who have often exhibited a fascination for science as a cultural activity and a deep and understanding of the way nature works.] I believe competition is to be avoided as much as possible. In fact this view applies to any interest – I thus have a problem with sport which is inherently competitive. My advice is to do something which interests you or which you enjoy (though I am not sure about the definition of enjoyment) and do it to the absolute best of your ability. If it interests you, however mundane it might seem on the surface, still explore it because something unexpected often turns up just when you least expect it. With this recipe, whatever your limitations, you will almost certainly still do better than anyone else. Having chosen something worth doing, never give up and try not to let anyone down.

This autobiography/biography was written at the time of the award and later published in the book series Les Prix Nobel/ Nobel Lectures/The Nobel Prizes. The information is sometimes updated with an addendum submitted by the Laureate.

Addendum, July 2012

Introduction

After the “eventful” two week period in September 1985 at Rice my whole research strategy changed essentially overnight. Instead of spending my weekends on graphics as I had always intended, I started working even harder on science than before. At my request Rick agreed that I must come back to work with his group to try to prove our conjecture. In the event I returned some nine or ten times over the next 1½ year period from September 1985 to April 1987, each time for a period of 2-3 weeks. The original structural conjecture was probed exhaustively during this period by joint Rice/Sussex experiments, by the independent Rice studies and also independent experimental and theoretical work by our group at Sussex.

Scientific Attitudes

It is important to realize that there are occasional moments in the life of a scientist when one has to be bold and I and the Rice team were conscious that this was one of those moments. We had proposed a possible structure to explain our discovery of a stable molecule with sixty carbon atoms but really had only this number to go on – and our intuition. I had the strong gut feeling that it was so beautiful a solution that it just had to be right. I do not remember during this early period thinking it could be wrong. I am sure that the other members of the team who had also lived through the exciting period of discovery had the same feeling. I decided however that I certainly must be ethical about this. I had a strong desire to work as hard as I could to prove the conjecture was right, but more importantly if it were not correct I definitely wanted to falsify the conjecture myself – I really did not want anyone else to prove that we were wrong. During the five-year period 1985, when we discovered C60, and 1990 when the Krätschmer and Huffman team extracted it, I worked with the Rice team, the Rice team worked independently and we worked independently at Sussex to assemble as much experimental and theoretical evidence as possible for the veracity of our original structural proposal. Indeed at Sussex we were only just pipped-at-the-post in confirming the structure unequivocally by the beautiful paper of Krätschmer and colleagues.