ADA YONATH

Nobel Prize in Chemistry 2009

Ever since she was a girl, Ada Yonath has set herself seemingly impossible goals, and then figured out how to reach them, step by step. As a young scientist she took on a challenge that others considered hopeless – mapping the structure of the ribosome – and persevered for decades until she succeeded. Her determination and ingenuity allowed researchers to see and understand the complex and crucial molecule. And since the ribosome is a major bacterial target for antibiotics, her work has led to new antibiotics and a better understanding of antibiotic resistance.

Ada Yonath was born in Jerusalem in 1939 to poor Jewish parents. Her family rented a single room in an apartment with two other families.

Despite her parents’ lack of resources or formal education, they supported their daughter’s evident curiosity and, with the help of an encouraging kindergarten teacher, sent her to a prestigious grammar school. At home, Yonath was always questioning.

“My mother said I was always asking, ‘Why is that red?’ and ‘Why do we have winter?’ and ‘Why is this liquid more viscous?’”

Ada Yonath

Aged five, Yonath undertook an ambitious effort to measure the height of her family’s balcony using two tables, a chair and stool. The experiment was suspended when she fell and broke her arm.

Life was hard, but it was about to get even harder. When Yonath was 11 years old, her father passed away after multiple hospital stays and operations. To help her ailing mother, Yonath cleaned, babysat, and tutored, while continuing to excel in school.

When the family moved to Tel Aviv a year later to be closer to her mother’s family, Yonath taught other students math and chemistry and even cleaned the chemistry lab in exchange for tuition. Her childhood in poverty made her accustomed to hard work and taught her to consider science itself a luxury.

1 (of 2) Cryo-cooling apparatus developed by Ada Yonath

Photo: Inter-University Research Institute Corporation, High Energy Accelerator Research Organization (KEK)

2 (of 2) Ada Yonath in the lab with Hakon Hope (left)

Photo: SSRL, Sanford University

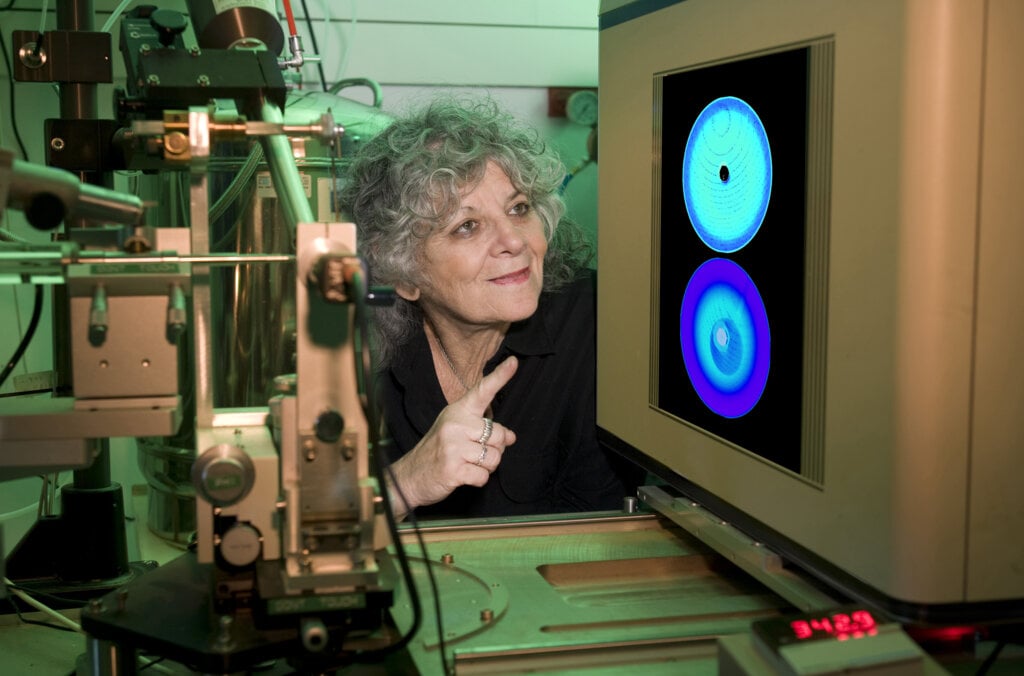

In the late 1970s, Yonath decided to focus on one of the mysteries of living cells: protein biosynthesis. She began with ribosomes, where protein synthesis occurs. These were still a puzzle to scientists because they had yet to determine ribosomes’ molecular structure. Normally one would use X-ray crystallography to map the structure of a molecule. But given its size, lack of internal symmetry and instability, the ribosome was considered impossible to crystallise – and Yonath was considered a dreamer or a fool for trying.

“I was met with reactions of disbelief and even ridicule in the international scientific community. I can compare this journey to climbing Mount Everest only to discover that a higher Everest stood in front of us.”

Ada Yonath

It took 25,000 tries – and the revelation that ribosomes from organisms that live under harsh conditions would be hardier during crystallisation. In the early 1980s, Yonath finally managed to crystallise a thermophile bacteria known as Geobacillus stearothermophilus.

The next step was to figure out a way to pass X-rays through the crystal without damaging its structure. The answer was cryo-bio-crystallography. Yonath developed this method of blasting the crystals at –185°C before X-raying them in order to protect their crystalline structures.

“I was described as a dreamer, a fantasist, even as the village idiot. I didn’t care. What I cared about was convincing people to allow me to go on with my work.”

Ada Yonath

By the mid-1990s, Yonath’s success had drawn other researchers into the effort. The wider team worked closely for several years, and in 2000 and 2001 reached the summit of their climb: they successfully mapped in three dimensions both subunits of the bacterial ribosome, for the very first time. For this achievement, in the face of daunting odds and widespread derision, Yonath was awarded the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 2009, along with crystallographers Venkatraman Ramakrishnan and Thomas A. Steitz.

Still at the Weizmann Institute, Yonath has gone on to demonstrate how more than 20 antibiotics function, paving the way for new products to be developed based on the structure of antibiotics bound to the ribosome. More recently, she has focused her efforts on the issues of antibiotic resistance. She also wants to uncover the very beginnings of life itself: how ribosomes first came into being and started creating proteins. It sounds ambitious, but for Ada Yonath, discovering the origin of life is just the next in a series of Mount Everests.

Speed read: Some assembly required

At first sight it seems simple enough: DNA makes RNA makes protein, and, by extension, you and me and every living thing. But this ‘central dogma of biology’, as Francis Crick famously called it, requires some stupendously complicated machinery to make it happen, and much of the last half century of research has been devoted to unravelling the apparatus that builds life. Nobel Prizes have recognized a number of the triumphs along the way, among them Watson, Crick and Wilkins‘ decipherment of the helical structure of DNA and Roger Kornberg‘s uncovering of the workings of the enzyme RNA polymerase, which turns DNA into RNA. Now, the 2009 Nobel Prize in Chemistry recognizes three people who have made major contributions to understanding the nature of the machine that translates the RNA code into protein: the ribosome.

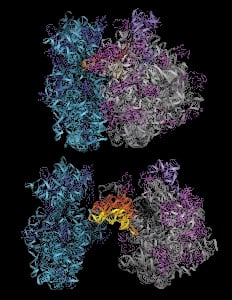

Venki Ramakrishnan, Thomas Steitz and Ada Yonath took the view that in order to be able to understand the ribosome, we have to be able first to visualize it. Using X-ray crystallography, an imaging technique in which the diffraction patterns formed by X-rays passing through a crystal of a substance are used to piece together that crystal’s atomic structure, they independently set out to ‘solve’ the structure of the ribosome. The tasks of preparing suitable ribosomal crystals for diffraction, and of interpreting the resulting X-ray diffraction patterns from such large and unsymmetrical entities, were at first widely viewed as impossible. But in 1980 Ada Yonath, working with the ribosomes of heat-loving bacteria that she thought might be especially robust, succeeded in preparing the first useful crystals of the larger of the ribosome’s two subunits. This marked the beginning of two decades of intense activity during which better and better crystals and images were obtained, and numerous technical hurdles were overcome, culminating with the publication of high resolution structures for both subunits in 2000. Further elaboration of the ribosomal structure has followed, with these and other groups contributing to our overall picture of how this molecular factory works to assemble protein chains.

As the target of 50% of known antibiotics, the bacterial ribosome is a structure of major therapeutic importance. With antibiotic resistance on the increase, it is hoped that an understanding of precisely how antibiotics interact with the ribosome will allow the design of new antibiotics to tackle drug-resistant bacteria. Ramakrishnan, Steitz and Yonath have all imaged the molecular interactions between ribosomes and antibiotics, providing key data to help guide structure-based drug design of new antibiotics.

Press release

English

Swedish

Hebrew (pdf)

7 October 2009

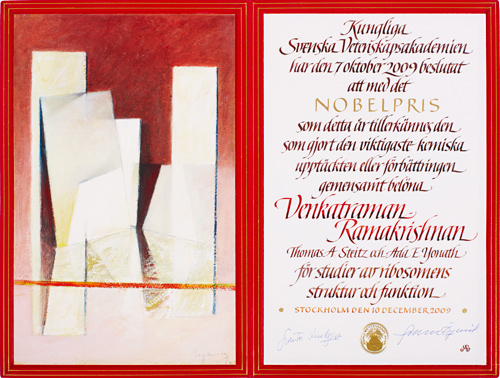

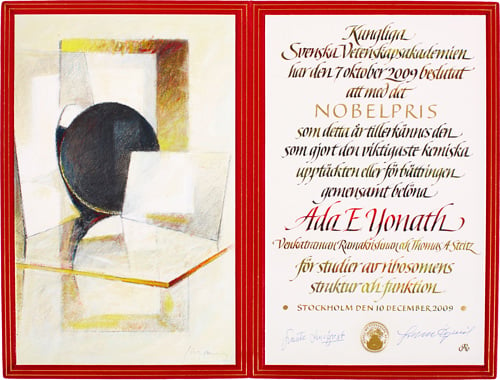

The Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences has decided to award the Nobel Prize in Chemistry for 2009 jointly to

Venkatraman Ramakrishnan

MRC Laboratory of Molecular Biology, Cambridge, United Kingdom

Thomas A. Steitz

Yale University, New Haven, CT, USA

Ada E. Yonath

Weizmann Institute of Science, Rehovot, Israel

“for studies of the structure and function of the ribosome”

The ribosome translates the DNA code into life

The Nobel Prize in Chemistry for 2009 awards studies of one of life’s core processes: the ribosome’s translation of DNA information into life. Ribosomes produce proteins, which in turn control the chemistry in all living organisms. As ribosomes are crucial to life, they are also a major target for new antibiotics.

This year’s Nobel Prize in Chemistry awards Venkatraman Ramakrishnan, Thomas A. Steitz and Ada E. Yonath for having showed what the ribosome looks like and how it functions at the atomic level. All three have used a method called X-ray crystallography to map the position for each and every one of the hundreds of thousands of atoms that make up the ribosome.

Inside every cell in all organisms, there are DNA molecules. They contain the blueprints for how a human being, a plant or a bacterium, looks and functions. But the DNA molecule is passive. If there was nothing else, there would be no life.

The blueprints become transformed into living matter through the work of ribosomes. Based upon the information in DNA, ribosomes make proteins: oxygen-transporting haemoglobin, antibodies of the immune system, hormones such as insulin, the collagen of the skin, or enzymes that break down sugar. There are tens of thousands of proteins in the body and they all have different forms and functions. They build and control life at the chemical level.

An understanding of the ribosome’s innermost workings is important for a scientific understanding of life. This knowledge can be put to a practical and immediate use; many of today’s antibiotics cure various diseases by blocking the function of bacterial ribosomes. Without functional ribosomes, bacteria cannot survive. This is why ribosomes are such an important target for new antibiotics.

This year’s three Laureates have all generated 3D models that show how different antibiotics bind to the ribosome. These models are now used by scientists in order to develop new antibiotics, directly assisting the saving of lives and decreasing humanity’s suffering.

Venkatraman Ramakrishnan, US citizen. Born in 1952 in Chidambaram, Tamil Nadu, India. Ph.D. in Physics in 1976 from Ohio University, USA. Senior Scientist and Group Leader at Structural Studies Division, MRC Laboratory of Molecular Biology, Cambridge, UK.

www.mrc-lmb.cam.ac.uk/ribo/homepage/ramak/index.html

Thomas A. Steitz, US citizen. Born in 1940 in Milwaukee, WI, USA. Ph.D. in Molecular Biology and Biochemistry in 1966 from Harvard University, MA, USA. Sterling Professor of Molecular Biophysics and Biochemistry and Howard Hughes Medical Institute Investigator, both at Yale University, CT, USA.

www.mbb.yale.edu/faculty/pages/steitzt.html

Ada E. Yonath, Israeli citizen. Born in 1939 in Jerusalem, Israel. Ph.D. in X-ray Crystallography in 1968 from the Weizmann Institute of Science, Israel. Martin S. and Helen Kimmel Professor of Structural Biology and Director of Helen & Milton A. Kimmelman Center for Biomolecular Structure & Assembly, both at Weizmann Institute of Science, Rehovot, Israel

www.weizmann.ac.il/sb/faculty_pages/Yonath/home.html

The Prize amount: SEK 10 million to be shared equally between the Laureates

Contacts: Erik Huss, Press Officer, phone +46 8 673 95 44, +46 70 673 96 50, [email protected]

Fredrik All, Editor, Phone +46 8 673 95 63, +46 70 673 95 63, [email protected]

The Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences, founded in 1739, is an independent organization whose overall objective is to promote the sciences and strengthen their influence in society. The Academy takes special responsibility for the natural sciences and mathematics, but endeavours to promote the exchange of ideas between various disciplines.

Pressmeddelande: Nobelpriset i kemi 2009

English

Swedish

Hebrew (pdf)

7 oktober 2009

Kungl. Vetenskapsakademien har beslutat utdela Nobelpriset i kemi år 2009 gemensamt till

Venkatraman Ramakrishnan

MRC Laboratory of Molecular Biology, Cambridge, Storbritannien

Thomas A. Steitz

Yale University, New Haven, CT, USA

Ada E. Yonath

Weizmann Institute of Science, Rehovot, Israel

“för studier av ribosomens struktur och funktion”

Ribosomen omvandlar DNA-koden till liv

Årets Nobelpris i kemi belönar studier av en av livets mest grundläggande processer: när ribosomer omvandlar informationen i DNA till liv. Ribosomer tillverkar proteiner, som i sin tur sköter kemin i alla levande organismer. Eftersom ribosomerna är fundamentala för livet, är de också perfekta mål för nya antibiotika.

Årets Nobelpris i kemi belönar Venkatraman Ramakrishnan, Thomas A. Steitz och Ada E. Yonath för att de har visat hur ribosomen ser ut och fungerar på atomnivå. Alla tre har arbetat med en metod som kallas röntgenkristallografi. Med hjälp av den har de kartlagt positionen för var och en av de hundratusentals atomer som bygger upp ribosomen.

Inuti varje cell, i varje levande varelse finns DNA-molekyler. De innehåller ritningen för hur en människa, en växt eller en bakterie ska se ut och fungera. Men DNA-molekylen är passiv. Om bara den fanns, skulle det inte bli något liv.

Ritningarna blir i stället till levande materia genom ribosomerna. Utifrån informationen i DNA bygger ribosomen proteiner: syretransporterande hemoglobin, immunförsvarets antikroppar, hormoner som insulin, hudens kollagen eller sockernedbrytande enzymer. Det finns tiotusentals proteiner i kroppen med olika form och funktion. De bygger och styr livet på kemisk nivå.

Kunskapen om ribosomens minsta beståndsdelar är viktig för den vetenskapliga förståelsen av liv. Och kunskapen kan också komma mänskligheten till omedelbar nytta; många av dagens antibiotika botar olika sjukdomar eftersom de specifikt slår ut bakteriers ribosomer. Utan fungerande ribosomer överlever inte bakterierna. Därför är ribosomerna viktiga mål vid utvecklingen av nya antibiotika.

Årets tre Nobelpristagare har alla tagit fram tre-dimensionella modeller som visar hur olika antibiotika fäster vid ribosomen. Dessa används nu av forskare för att ta fram nya antibiotika. Kunskapen kan därför direkt bidra till att rädda liv och minska lidande.

Venkatraman Ramakrishnan, amerikansk medborgare. Född 1952 (57 år) i Chidambaram, Tamil Nadu, Indien. F.D. i fysik 1976 vid Ohio University, USA. Senior Scientist och Group Leader vid Structural Studies Division, MRC Laboratory of Molecular Biology, Cambridge, Storbritannien.

www.mrc-lmb.cam.ac.uk/ribo/homepage/ramak/index.html

Thomas A. Steitz, amerikansk medborgare. Född 1940 (69 år)i Milwaukee, WI, USA. F.D. i molekylärbiologi och biokemi 1966 vid Harvard University, MA, USA. Sterling Professor of Molecular Biophysics and Biochemistry och Howard Hughes Medical Institute Investigator, båda vid Yale University, CT, USA.

www.mbb.yale.edu/faculty/pages/steitzt.html

Ada E. Yonath, israelisk medborgare. Född 1939 (70 år) i Jerusalem, Israel. F.D. i röntgenkristallografi 1968 vid Weizmann Institute of Science, Israel. Martin S. and Helen Kimmel Professor of Structural Biology och Director vid Helen & Milton A. Kimmelman Center for Biomolecular Structure & Assembly, båda vid Weizmann Institute of Science, Rehovot, Israel.

www.weizmann.ac.il/sb/faculty_pages/Yonath/home.html

Prissumma: 10 miljoner svenska kronor, delas lika mellan pristagarna

Kontaktpersoner: Erik Huss, pressansvarig, tel. 08-673 95 44, 070-673 96 50, [email protected]

Fredrik All, redaktör, tel. 08-673 95 63, 070-673 95 63, [email protected]

Kungl. Vetenskapsakademien, stiftad år 1739, är en oberoende organisation som har till uppgift att främja vetenskaperna och stärka deras inflytande i samhället. Av hävd tar akademien särskilt ansvar för naturvetenskap och matematik, men strävar efter att öka utbytet mellan olika discipliner.

Thomas A. Steitz – Other resources

Links to other sites

On Thomas Steitz from Yale University

Venkatraman Ramakrishnan – Other resources

Links to other sites

Venkatraman Ramakrishnan’s page at MRC Laboratory of Molecular Biology, Cambridge, United Kingdom

Going places: an interview with Venkatraman Ramakrishnan from IndiaBioscience

Ada E. Yonath – Photo gallery

1 (of 24)

Ada E. Yonath receiving her Nobel Prize from His Majesty King Carl XVI Gustaf of Sweden at the Stockholm Concert Hall, 10 December 2009.

Copyright © The Nobel Foundation 2009

Photo: Frida Westholm

2 (of 24)

Ada E. Yonath after receiving her Nobel Prize at the Stockholm Concert Hall, 10 December 2009.

Copyright © The Nobel Foundation 2009

Photo: Frida Westholm

3 (of 24)

Close-up of the Nobel Laureates in Chemistry (from left to right): Venkatraman Ramakrishnan, Thomas A. Steitz and Ada E. Yonath.

Copyright © The Nobel Foundation 2009

Photo: Frida Westholm

4 (of 24)

The 2009 Nobel Laureates stand for the Swedish national anthem (from left to right): Charles K. Kao, Willard S. Boyle, George E. Smith, Venkatraman Ramakrishnan, Thomas A. Steitz, Ada E. Yonath, Elizabeth H. Blackburn, Carol W. Greider, Jack W. Szostak, Herta Müller, Elinor Ostrom and Oliver E. Williamson.

Copyright © The Nobel Foundation 2009

Photo: Frida Westholm

5 (of 24)

Ada E. Yonath with her grand-daughter, Noa (left), and her sister, Mrs Nurit Raviv (right), after the Nobel Prize Award Ceremony in Stockholm.

Copyright © The Nobel Foundation 2009

Photo: Frida Westholm

6 (of 24)

Nobel Laureate Ada E. Yonath in conversation with His Majesty King Carl XVI Gustaf of Sweden at the Nobel Banquet.

Copyright © The Nobel Foundation 2009

Photo: Orasisfoto

7 (of 24) Ada E. Yonath delivering her banquet speech.

© The Nobel Foundation 2009. Photo: Orasisfoto.

8 (of 24)

From left to right: Princess Madeleine, Crown Princess Victoria, Nobel Laureate Venkatraman Ramakrishnan, Mrs Vera Rosenberry Ramakrishnan, Hagith Yonath, Nobel Laureate Ada E. Yonath, His Majesty King Carl XVI Gustaf of Sweden, Her Majesty Queen Silvia, Joan Argetsinger Steitz, Nobel Laureate Thomas A. Steitz, and Prince Carl Philip at the Nobel Banquet.

Copyright © The Nobel Foundation 2009

Photo: Orasisfoto

9 (of 24)

The 2009 Nobel Laureates assembled for a group photo during their visit to the Nobel Foundation, 12 December 2009. Back row, left to right: Nobel Laureates in Chemistry Ada E. Yonath and Venkatraman Ramakrishnan, Nobel Laureates in Physiology or Medicine Jack W. Szostak and Carol W. Greider, Nobel Laureate in Chemistry Thomas A. Steitz, Nobel Laureate in Physiology or Medicine Elizabeth H. Blackburn, and Nobel Laureate in Physics George E. Smith. Front row, left to right: Nobel Laureate in Physics Willard S. Boyle, Laureate in Economic Sciences Elinor Ostrom, Nobel Laureate in Literature Herta Müller and Laureate in Economic Sciences, Oliver E. Williamson.

Copyright © The Nobel Foundation 2009

Photo: Orasisfoto

10 (of 24)

Venkatraman Ramakrishnan, Thomas A. Steitz and Ada E. Yonath after delivering their Nobel Lectures at the Aula Magna, Stockholm University, 8 December 2009.

Copyright © The Nobel Foundation 2009

Photo: Orasisfoto

11 (of 24)

Ada E. Yonath delivering her Nobel Lecture at the Aula Magna, Stockholm University, 8 December 2009.

Copyright © The Nobel Foundation 2009

Photo: Orasisfoto

12 (of 24)

Venkatraman Ramakrishnan (centre), with fellow Chemistry Laureates Ada E. Yonath (left) and Thomas A. Steitz (right) during their interview with Nobelprize.org in Stockholm, 6 December 2009.

The interviewer is Adam Smith, Editor-in-Chief of Nobelprize.org.

Copyright © Nobel Media AB 2009

Photo: Niclas Enberg

13 (of 24)

Ada E. Yonath (left), Thomas A. Steitz (center) and Venkatraman Ramakrishnan (right) leaves the interview with Nobelprize.org at Grand Hôtel in Stockholm, 6 December 2009.

Copyright © Nobel Media AB 2009

Photo: Niclas Enberg

14 (of 24) Ada E. Yonath with x-ray diffraction equipment.

Credits: Micheline Pelletier/Corbis

15 (of 24) Professor Ada Yonath (right) discussing the outcome of an experiment with her assistant, Anat Bashan (left), at the European Synchrotron Radiation Facility (ESRF) in Grenoble, France.

Credits: Micheline Pelletier/Corbis

16 (of 24) Professor Ada Yonath with some members of her team at the European Synchrotron Radiation Facility (ESRF) in Grenoble, France. Jacob Halfov (far left), Haim Rozenberg, Ella Zimmerwain, Itai Wekselman, Chen Davidovich, Anat Bashan and Yehada Halfon (far right).

Credits: Micheline Pelletier/Corbis

17 (of 24) Professor Ada Yonath preparing frozen crystals at the European Synchrotron Radiation Facility (ESRF) in Grenoble, France.

Credits: Micheline Pelletier/Corbis

18 (of 24) Ada E. Yonath with dishes used for crystallization experiments.

Credits: Micheline Pelletier/Corbis

19 (of 24) Professor Ada Yonath in the Weizmann Institute library.

Credits: Micheline Pelletier/Corbis

20 (of 24) Professor Ada Yonath preparing frozen crystals for an experiment at the European Synchrotron Radiation Facility (ESRF) in Grenoble, France.

Credits: Micheline Pelletier/Corbis

21 (of 24) Professor Ada Yonath with her daughter, Hagith Yonath, and her grand-daughter, Noa, in the Jerusalem neighborhood where she spent her childhood.

Credits: Micheline Pelletier/Corbis

22 (of 24) Ada Yonath on the stairs of the house where she spent her childhood in a suburb of Jerusalem.

Credit: Micheline Pelletier/Corbis

23 (of 24) Ada Yonath (left) and Venkatraman Ramakrishnan (right) in Cambridge, United Kingdom, September 2009.

Kindly provided by Venkatraman Ramakrishnan

24 (of 24) Ada Yonath (left) and Thomas A. Steitz (right) in Sandhamn, Sweden, 2003.

Kindly provided by Venkatraman Ramakrishnan

Venkatraman Ramakrishnan – Photo gallery

1 (of 19)

Venkatraman Ramakrishnan receiving his Nobel Prize from His Majesty King Carl XVI Gustaf of Sweden at the Stockholm Concert Hall, 10 December 2009.

Copyright © The Nobel Foundation 2009

Photo: Frida Westholm

2 (of 19)

Venkatraman Ramakrishnan after receiving his Nobel Prize at the Stockholm Concert Hall, 10 December 2009.

Copyright © The Nobel Foundation 2009

Photo: Hans Mehlin

3 (of 19)

Close-up of the Nobel Laureates in Chemistry (from left to right): Venkatraman Ramakrishnan, Thomas A. Steitz and Ada E. Yonath.

Copyright © The Nobel Foundation 2009

Photo: Frida Westholm

4 (of 19)

The 2009 Nobel Laureates stand for the Swedish national anthem (from left to right): Charles K. Kao, Willard S. Boyle, George E. Smith, Venkatraman Ramakrishnan, Thomas A. Steitz, Ada E. Yonath, Elizabeth H. Blackburn, Carol W. Greider, Jack W. Szostak, Herta Müller, Elinor Ostrom and Oliver E. Williamson.

Copyright © The Nobel Foundation 2009

Photo: Frida Westholm

5 (of 19)

Seated at the table of honour at the Nobel Banquet are (from left to right): Nobel Laureate Thomas A. Steitz, Crown Princess Victoria and Nobel Laureate Venkatraman Ramakrishnan.

Copyright © The Nobel Foundation 2009

Photo: Orasisfoto

6 (of 19)

From left to right: Princess Madeleine, Crown Princess Victoria, Nobel Laureate Venkatraman Ramakrishnan, Mrs Vera Rosenberry Ramakrishnan, Hagith Yonath, Nobel Laureate Ada E. Yonath, His Majesty King Carl XVI Gustaf of Sweden, Her Majesty Queen Silvia, Joan Argetsinger Steitz, Nobel Laureate Thomas A. Steitz, and Prince Carl Philip at the Nobel Banquet.

Copyright © The Nobel Foundation 2009

Photo: Orasisfoto

7 (of 19)

The 2009 Nobel Laureates assembled for a group photo during their visit to the Nobel Foundation, 12 December 2009. Back row, left to right: Nobel Laureates in Chemistry Ada E. Yonath and Venkatraman Ramakrishnan, Nobel Laureates in Physiology or Medicine Jack W. Szostak and Carol W. Greider, Nobel Laureate in Chemistry Thomas A. Steitz, Nobel Laureate in Physiology or Medicine Elizabeth H. Blackburn, and Nobel Laureate in Physics George E. Smith. Front row, left to right: Nobel Laureate in Physics Willard S. Boyle, Laureate in Economic Sciences Elinor Ostrom, Nobel Laureate in Literature Herta Müller and Laureate in Economic Sciences, Oliver E. Williamson.

Copyright © The Nobel Foundation 2009

Photo: Orasisfoto

8 (of 19) Venkatraman Ramakrishnan during a visit to Rinkeby School in Stockholm on 9 December 2009.

Photo: Lotta Silfverhielm Kindly provided by Lotta Silfverhielm

9 (of 19) Venkatraman Ramakrishnan signing autographs for pupils during a visit to Rinkeby School in Stockholm on 9 December 2009.

Photo: Karin Sohlgren Kindly provided by Karin Sohlgren

10 (of 19)

Venkatraman Ramakrishnan photographed by students after the Nobel Lecture in Stockholm, 8 December 2009.

Copyright © The Nobel Foundation 2009

Photo: Orasisfoto

11 (of 19)

Venkatraman Ramakrishnan, Thomas A. Steitz and Ada E. Yonath after delivering their Nobel Lectures at the Aula Magna, Stockholm University, 8 December 2009.

Copyright © The Nobel Foundation 2009

Photo: Orasisfoto

12 (of 19)

Venkatraman Ramakrishnan delivering his Nobel Lecture at the Aula Magna, Stockholm University, 8 December 2009.

Copyright © The Nobel Foundation 2009

Photo: Orasisfoto

13 (of 19)

Venkatraman Ramakrishnan during the reception at the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences in Stockholm, 7 December 2009.

Copyright © The Nobel Foundation 2009

Photo: Orasisfoto

14 (of 19)

Venkatraman Ramakrishnan (centre), with fellow Chemistry Laureates Ada E. Yonath (left) and Thomas A. Steitz (right) during their interview with Nobelprize.org in Stockholm, 6 December 2009.

The interviewer is Adam Smith, Editor-in-Chief of Nobelprize.org.

Copyright © Nobel Media AB 2009

Photo: Niclas Enberg

15 (of 19)

Ada E. Yonath (left), Thomas A. Steitz (center) and Venkatraman Ramakrishnan (right) leaves the interview with Nobelprize.org at Grand Hôtel in Stockholm, 6 December 2009.

Copyright © Nobel Media AB 2009

Photo: Niclas Enberg

16 (of 19) Venkatraman Ramakrishnan, like many Nobel Laureates before him, autographs a chair at Kafé Satir at the Nobel Museum in Stockholm, 6 December 2009.

Copyright © The Nobel Museum 2009 Photo: Jonas Ekströmer

17 (of 19) The Ramakrishnan Lab on the day of the announcement of the 2009 Nobel Prize in Chemistry. Professor Venkatraman Ramakrishnan stands to the far left.

Credits: MRC Laboratory of Molecular Biology

18 (of 19) Ada Yonath (left) and Venkatraman Ramakrishnan (right) in Cambridge, United Kingdom, September 2009.

Kindly provided by Venkatraman Ramakrishnan

19 (of 19) Thomas A. Steitz (left) and Venkatraman Ramakrishnan (right) in Erice, Sicily, 2006.

Kindly provided by Venkatraman Ramakrishnan

Venkatraman Ramakrishnan – Nobel diploma

Copyright © The Nobel Foundation 2009

Artist: Jean-Louis Maurin

Calligrapher: Annika Rücker

Book binder: Ingemar Dackéus

Photo reproduction: Lovisa Engblom

Ada E. Yonath – Nobel diploma

Copyright © The Nobel Foundation 2009

Artist: Jean-Louis Maurin

Calligrapher: Annika Rücker

Book binder: Ingemar Dackéus

Photo reproduction: Lovisa Engblom