Transcript from an interview with Dan Shechtman

Interview with the 2011 Nobel Laureate in Chemistry Dan Shechtman, 6 December 2011. The interviewer is Adam Smith, Editorial Director of Nobel Media.

Daniel Shechtman, welcome to Stockholm.

Dan Shechtman: Thank you.

You are here to receive the Nobel Prize in Chemistry for your discovery of quasicrystals. It seems to me that there is a parallel to your discovery and that made by Wilhelm Röntgen, who received the very first Nobel Prize in Physics in 1901. In both cases there was an observation which many people, the majority of people would have just ignored. But that you, and in Röntgen’s case he, had the tenacity to take seriously. You saw the electron diffraction pattern and you didn’t let it go, you stuck with it.

Dan Shechtman: That is corrects. I know of course about the Röntgen story, I read about him and today I showed my family – in the museum – the exhibition they have about him. An excellent discovery of course. Let’s talk about Röntgen for a minute. A year after Röntgen made the discovery in 1895, x-rays were already used for medical purposes but only until von Laue, in 1912, did his famous experiment, did people know what it was really about. They knew that there was some radiation but they did not know what it was. So it took quite a few years, 17 years, between discovery and a real understanding of what it was. Both Röntgen – the great – and myself, we stumbled upon the discovery, it just happened, we saw it, but we made the observation and didn’t let go. We investigated it more and more. But not only Röntgen, many other discoveries that received the Nobel Prize – people just happens to see them and say Hm, that’s interesting, and continue to work. My case is just one of them.

Yes. It’s the case of that Pasteur thing of chance favouring the prepared mind, people knowing enough to take things seriously.

Dan Shechtman: Yes.

To know what to pay attention to. Here, in these /- – -/ surroundings, is a very far cry from you in your office in the National Institute of Standards and Technology in 1982 with this picture in front of you which you were taking seriously but everybody else were saying, Ignore it, Danny.

Dan Shechtman: Not everybody, I will tell you what was the span of reactions. Shall I? Okey, good. Let’s talk about the good people – the good side – my host for instance, John Cahn. He said to me, Danny, this is trying to tell us something and I challenge you to find out what it is. This was the good reaction. Bad reaction: my group leader came to my office one day – this was in the first month that I was talking about, this material – smiling /- – -/ he put an x-ray diffraction book on my desk and said something like, Danny, please read this book so that you understand that what you are saying can not be.

And this is because this picture you had seemed to defy the possibilities that were allowed under crystallography in those days?

Dan Shechtman: That is correct. But it was not one picture, it was a long series of experiments. The famous diffraction picture is one of very many experiments, all done by electron microscopy, transmission electron microscopy. So, he gave me the book and said, Please read. I said, I know this book, I am a teacher at the Technion I teach these things and I don’t need to read it. I am telling you this is something different, it’s not in the book. He took the book and sometime later – now I don’t remember how many days or how many hours it was – but he came back and said, Danny, you are a disgrace to my group and I want you to leave my group, I don’t want to be associated with this. So he moved to another group. This didn’t mean much, it sounds traumatic but it was not, I just had to find another group leader who would to adopt me – the orphan, the scientific orphan – and somebody did. The only amendment was instead of reporting to this secretary I reported to that secretary. I didn’t move from my office or from my laboratory, it was just about the same, so it was not very traumatic – now when people hear about it, Wow, thrown away from your group! Yes, but it was, not for me at least, it was not traumatic. It was not nice, I didn’t feel very good about it, but … This was a span of reactions between encouragement and rejection – and everything was somewhere in between.

But it takes a particular sort of person to stick to their guns even though they don’t know what they are looking at, they don’t know what the explanation is for this. You seem to have found something new but at the same time you haven’t got a clue presumably, at that point, of what might be causing it.

Dan Shechtman: The is correct but they knew what it was not. I knew that it was not twins – I will explain. In a periodic crystal there are different defects including grain boundaries of crystal boundaries. Imagine that this is a group of atomic plain and here is another crystal and sometimes they match in a certain way which is very peculiar, very precise the way they match. This is called a twin boundary. If you take five of them and take a diffraction of all of them together, then there is a five-fold symmetry. But it is a pseudo five-fold symmetry, because it is not taken from one crystal, it is taken from five crystals. These are called twin boundaries and the crystals are called twins, because they look like twins. I was looking for the twins. In the first minutes of the observation I was looking for the twins and performed the serial experiments and you can see that on my log book page which became famous – it was meant for me to read only but by now everybody saw that page – you could see this serial of experiments on that page and in day one I knew that it was not twins, but I didn’t know what it was. That took some time.

It’s having the confidence in your craft it’s knowing that you know enough about the experiment to trust what you have done, and that doesn’t come easily, it takes time.

Dan Shechtman: My tool was, my main tool still is an electron microscope, a transmission electron microscope. A transmission electron microscope is a very powerful tool to investigate structure of matter. Because the resolution of /- – -/ microscopes is very high you can actually see atoms – and you could see atoms 30 years ago also – now we have better resolutions, but you could see them. You could get a lot of information about not only the structure of the material but about the chemical composition. You can really investigate deep into the structure and understand what’s going on within it. This is something that you cannot do with x-rays unless you have large enough crystals. Our crystals were about two microns each, too small to get a single crystal x-ray diffraction but large enough to get a single crystal electron diffraction. If you have many many tiny crystals – like that – and you take an x-ray diffraction you lose the rotational symmetry, you do not see the rotation symmetry of one crystal. You could not have discovered quasiperiodic materials with x-rays, you had to work with electron microscopy. Electron microscopy, at least in methods that I was using at the time, was not as precise as x-rays. The people that rejected the results of electron microscopy on the grounds that they are not precise were correct, they are not precise, but you did not need the precision to see the rotation symmetry and my diffraction pattern showed that very clearly, you can see clearly the rotation symmetry.

What was the project that you were actually doing, because you weren’t looking for quasicrystals, you were making these alloys. What were you off looking for?

Dan Shechtman: My project … Let me start a little bit earlier. I came to NBS for my first sabbatical from the Technion. This is six years after I became a faculty, on the seventh year we have a sabbatical. I went there and actually stayed for two years, I requested one year of leave of absence. The sponsor was DARPA, Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency. They wanted me to develop aluminum base alloys for aerospace applications. I did it with a technique called rapid solidification in which you take a metal, you melt it and you solidify it, but very quickly, very rapidly. We had some instruments to do that, to solidify. When you rapidly solidify you move away from the /- – -/ stability, it is not /- – -/ to make them stable. You receive structures, meaning atomic arrangements which you cannot receive if you slowly cool.

You capture different structures?

Dan Shechtman: They form, different structures form. I started to work on an alloy that they gave me upon my arrival, it was an aluminum alloy. They said, Oh Danny, before you prepare your own alloys, here is something that we have for you, we already prepared this, so I started to work on aluminum alloys. Then there was a phase there which was close to aluminum six iron that was not stable. I wanted to see how it looks when it is stable, so I prepared alloys from, instead of aluminum iron aluminum manganese and I prepared a series of alloys – 1 % manganese, 2 %, 5 %, 10 % – maybe 10 alloys. In the aluminum 25 % manganese there it was. Let me tell you something that is a little bit educational. The person who sponsored me in DAPA – now this is department of defense of the United States – he knew me, and he said, Danny, you have a very nice proposal which I am sponsoring, but I am telling you run wild. Do whatever you want! Don’t just stick to the proposal, just run wild. What did it mean? You see, aluminum 1 % manganese, maybe up to 5 % manganese can be used for, but 15 %, 25 % is almost powder. You cannot make anything useful for aerospace from that. But I felt free to do whatever I wanted. You start from applications, but you end up in good science.

That’s a lovely thing to bring up because so often we sit talking to Nobel Laureates who have been doing basic science and they have come up with a basic discovery, and naturally people start asking, What is the application? In your case you were doing applied research, and the basic research was your side piece – it’s very nice. Is the lesson to learn from that even when thinking that you are directing people down the applied search tracks there should always be the space for play?

Dan Shechtman: You should look around and pay attention to something odd. When I talk to young students, I can give them ten advice but I always give them one advice. If you want to succeed in something – become an expert in that field. You can start becoming an expert now, when you are a high school student. Choose a subject that may interest you and in today’s world information is regularly available to everybody everywhere. Choose a subject and become an expert. If you have questions call a professor in the university, he will talk to you, he will explain to you. Find out who are the people who are the masters of that field and talk to them. Become an expert and it will carry you a long way.

Because expertise will always be sort out by others?

Dan Shechtman: No, because as an expert you will … When you will discover something you will trust your findings. Also you are right. It pays to become an expert and sometimes it doesn’t. Let me give an example. In my early days in academia, I was going to the US every summer to work there. I am a material scientist and I wanted to be labelled material scientist, but I was labelled as an electron microscopist instead. One summer I called them and asked, Can I come this summer? He said, No, this summer we don’t need any electron microscopist. I said, Now wait, I am a material scientist. No, no, but you are a good electron microscopist. I was labelled as an electron microscopist. Sometimes it is good, sometimes it is not very good to put a label on somebody in a narrow filed.

We’ll come back to quasicrystals in a minute, but I just wanted to make a brief digression into becoming an expert because how did you become an expert yourself, how did you become a material scientist?

Dan Shechtman: Let me tell you. When I was very young, in the fifth grade in elementary school, I was very interested in nature and science. The nature teacher – we had a subject called nature – which is now called science – then it was called nature – said to the children, You know we have a microscope in school, and my eyes opened like that. What? Can you bring it to the class? He said, Yes, of course. The next week he didn’t bring it and the next week he didn’t bring it and I begged him and begged him, so finally he brought it to the class and put it on the table. It was a microscope like this, a very primitive one, but I had never seen one before. He put a sample of a leaf or an insect, I don’t know what it was, I think it was a leaf or something. He said, Dan, you showed an interest in this so you will be first to look. I came and I stood at his desk and I was looking, Wow, it was so amazing. He said, OK Dan, sit down. I said, Wait a minute, I was so fascinated. Then I said, Maybe you could bring it to the class every week or may I come to the warehouse where you store it, can I work on it? No, he said, one time is enough, and he never brought it again.

This was my first encounter with a microscope, it was a small, primitive optical microscope. When I did my master’s degree at the Technion the first transmission microscope arrived at the Technion and I immediately pounced on it. I was circling around when they assembled it, asked so many questions, and looked at it – more like a mechanical engineer than anything else, just wanted to see the construction. Then I became one of the first operators of the electron microscope. At that time we were used to fix the electron microscope ourselves, there was no technician, we did it. People ask me, Did you spend time on the microscope or under the microscope? It was equal time, but I learned how the microscope works, really, learned the technique. Then my PhD was already on electron microscopy.

Again, it underlines that once you found yourself in America observing these odd patterns you knew the instrument inside out and you knew where any such deviation could come from.

Dan Shechtman: I knew where it could come from and suddenly it was right there on the first day, the record showed clearly what I did

There was a gap in your history between the microscope you were showed once and then was taken away and your master’s degree. Somebody else must have encouraged you. Was there one person or someone who pushed you?

Dan Shechtman: Yes, I can say that there was one professor that arrived at my department from Cambridge in England. He was /- – -/ microscopy, one of the first in electron microscopy, David Brandon. He was my thesis supervisor for PhD. I came to him when I did my master and said, Will you instruct me for a PhD and he said, Of course, why not. This is the way we started, and he gave me the first lessons about electron microscopy. He did some other thing that should be told, he introduced me to the masters of electron microscopy of the time. Most of them were from England and from Belgium. They came to visit him and he invited me to his home every time somebody came to visit. He introduced me to this community. This is important, this is a lesson to be learned. Later on, he sent me to an international school of electron microscopy in Erice, Italy – Sicily actually. That was another important thing – send your students to become experts.

Back to quasicrystals. The story is well told in the materials published already, and of course you will be telling the story, I suspect, in your Nobel Lecture in a couple of days’ time and how gradually an understanding of what was generating this aperiodic pattern. I guess we don’t want to go into that in great detail now, but what your discovery of quasicrystals did was to change the definition of how we saw matter. Before then crystals were described in one way as series of repeating units. After quasicrystals it became a much broader definition and that seems to be a truly exciting thing to happen.

Dan Shechtman: Yes. The science of crystallography started in 1912, really the science, by the famous experiments by von Laue, he did x-ray diffraction. It was an amazing experiment because he proved in one experiment that x-rays have /- – -/ and also that solid matter crystals are really organised in planes and the atoms are really nicely ordered. Also, in the alloy that he studied the order was periodic. In those seventy years, from 1912 to 1982, the only crystals that was studied and analysed were periodic. And so a paradigm was evolved that a crystal – a paradigm and a definition – a crystal is order and periodic, anything that is not both ordered and periodic is not a crystal. OK. So here I am with a diffraction pattern and a serial of experiments that show that I have something which doesn’t fit the definition of crystals because it is not periodic. It’s ordered, how do you recognise order, because of the diffraction pattern, but it is not periodic. For three years, 1984-1987, the international union of crystallography did not accept the new findings into the community of crystals, they did not accept it as a crystal. Why? Because our results came from electron microscopy and not from x-rays.

Why couldn’t we do x-ray diffraction? I did x-ray diffraction experiments, a lot of diffraction experiments – the only famous experiments I did was electron microscopy because then you can see single crystals. We didn’t have single crystals large enough for x-rays. It took three years for somebody to grow large enough quasiperiodic crystals. In two laboratories, both in France and in Japan, my colleagues had x-ray diffraction patterns and they sent them to me. In 1987 I presented these results in a meeting of the international union of crystallography in Perth, this is Western Australia. The the community said, OK, Danny, now you’re talking. They established a committee to deal with non-periodic structures and the new definition have emerged. They saw the diffraction pattern not based on the real space based on /- – -/ space. It’s a wonderful definition because it is a humble definition. A humble scientist is a good scientist, open.

So many people, I suppose the majority of people, view sciences providing /- – -/ sort of closing down things – this is how this works, this is how this works. In this case this is a piece of science that says, Well, actually we knew less than we thought we did, it’s going in this direction.

Dan Shechtman: Yes, but this is quite typical in science, we open new avenues all the time. Look at the Nobel Prize in Physics this year – a new avenue. Our understanding of the universe – this year is the year of chemistry …

The international year of chemistry.

Dan Shechtman: Yes, I am honoured to receive the Nobel Prize this year. In two years we will have the year of crystallography, not after von Laue by the way, but after Bragg – this is a different story. Look at the physicists, the large world of astronomy is developing all the time, but so is the small world of the structure of matter, and smaller and smaller is developing in two directions. We reach deeper and deeper into the understanding of elementary particles and of our universe. Do we have only one universe?

Who knows?

Dan Shechtman: People thought before that the earth is the centre of the universe and the stars are to serve us. Then we understood we are just a small piece in a universe. Then suddenly we discovered that we have galaxies, we are not the only galaxies, we have many galaxies, so now we have a universe, why should we assume that we have only one universe? We’re never unique. Science is evolving all the time and rightly so. We should be happy that there are so many mysteries to be solved, our children and grandchildren should also be scientific.

There’s plenty of opportunities out there.

Dan Shechtman: Yes, definitely, the more we know, the more we don’t know.

Last piece dwelling on quasicrystals. They are very small. As you’ve been saying, the crystals you were studying were too small for x-ray diffraction. But quasicrystals in nature are also very small, they have now been found to exist out there.

Dan Shechtman: Yes, indeed.

But in very micro forms, is that correct?

Dan Shechtman: Yes, but no. You can grow large single crystals, you can grow large single crystals as large as my pen. You can grow single quasi periodic materials like this, there is no reason why you shouldn’t. You can make quasi periodic materials in each and every way you make any other material. Up to the recent discovery of Paul Steinhardt and his student of quasi periodic materials in nature most of the quasi crystals, if not all, were intermetallic compounds, so they are intermetallic compounds – nothing very special about that – but the structure is very special. They are not small, you can grow them large.

What do you hope that they will bring mankind, because there’s a lot of talk of application for them.

Dan Shechtman: The best application is here in Sweden, in my opinion, a company named Sandvik, you probably know of Sandvik, they have headquarter in Sandviken. They have a steel which is extremely strong, it is a wonderful steel and it is strengthened by quasiperiodic particles – this is one use. In order to use a material you need some property that will be special, a special property. We look for these special properties and we combine them with the price of the material and with the corrosion resistance of the material and the beauty of the material. Once you find a good combination you can start using the material. I wouldn’t get the Nobel Prize for the applications but there are a few applications that are there and there will be application /- – -/. Not necessarily in the realm of materials. Maybe in optics, maybe in magnetic properties. These are not unique materials and just bringing to the different sciences the new order, which is not periodic, it can be used. Look at what’s happening in the field of optics today with quasi periodic material, it’s quite amazing.

There are possibilities. Thank you very much indeed. I am afraid we have run out of time. It has been a great pleasure to speak to you and I wish you a very enjoyable Nobel Week.

Dan Shechtman: Thank you very much. A pleasure to be here.

Thank you.

Did you find any typos in this text? We would appreciate your assistance in identifying any errors and to let us know. Thank you for taking the time to report the errors by sending us an e-mail.

Dan Shechtman – Other resources

Links to other sites

Dan Shechtman’s page at Iowa State University

Dan Shechtman – Photo gallery

Dan Shechtman receiving his Nobel Prize from His Majesty King Carl XVI Gustaf of Sweden at the Stockholm Concert Hall, 10 December 2011.

Copyright © The Nobel Foundation 2011

Photo: Frida Westholm

Dan Shechtman after receiving his Nobel Prize at the Stockholm Concert Hall, 10 December 2011.

Copyright © The Nobel Foundation 2011

Photo: Frida Westholm

Dan Shechtman with family and friends after the Nobel Prize Award Ceremony, 10 December 2011.

Copyright © The Nobel Foundation 2011

Photo: Lina Göransson

Mrs Claudia Steinman, wife of the late Medicine Laureate Ralph M. Steinman, arrives at the Nobel Banquet accompanied by Chemistry Laureate Dan Shechtman.

Copyright © The Nobel Foundation 2011

Photo: Orasisfoto

Dan Shechtman and Mrs Claudia Steinman, wife of the late Medicine Laureate Ralph M. Steinman, at the Nobel Banquet, 10 December 2011.

Copyright © The Nobel Foundation 2011

Photo: Orasisfoto

Dan Shechtman delivering his banquet speech.

© The Nobel Foundation 2011. Photo: Orasisfoto

Eleven of the thirteen 2011 Nobel Laureates assembled for a group photo during their visit to the Nobel Foundation in Stockholm, 12 December 2011. Back row, left to right: Nobel Peace Prize Laureates Tawakkol Karman and Leymah Gbowee, Nobel Laureates in Physics Brian P. Schmidt, Saul Perlmutter and Adam G. Riess, Nobel Laureate in Chemistry Dan Shechtman and Nobel Laureate in Physiology or Medicine Bruce A. Beutler. Front row, left to right: Nobel Peace Prize Laureate Ellen Johnson Sirleaf, Laureate in Economic Sciences Christopher A. Sims, Nobel Laureate in Literature Tomas Tranströmer and Laureate in Economic Sciences Thomas J. Sargent.

© The Nobel Foundation 2011. Photo: Orasisfoto

Recording of Nobel Media's TV-program 'Nobel Minds', hosted by Zeinab Badawi, BBC World News, in the Bernadotte Library at the Royal Palace, 9 December 2011.

Photo: Claes Löfgren Copyright Nobel Media AB 2011

Dan Shechtman at Nobel Media's recording of the TV-program 'Nobel Minds' in the Bernadotte Library at the Royal Palace, 9 December 2011.

Photo: Claes Löfgren Copyright Nobel Media AB 2011

Dan Shechtman delivering his Nobel Lecture at Aula Magna, Stockholm University, on 8 December 2011.

Copyright © The Nobel Foundation 2011

Photo: Orasisfoto

Like many Nobel Laureates before him, Dan Shechtman autographs a chair at Bistro Nobel at the Nobel Museum in Stockholm, 6 December 2011.

Copyright © Scanpix 2011 Photo: Jonas Ekströmer

Portrait of Dan Shechtman.

Photo: Technion Israel Institute of Technology

Dan Shechtman – Nobel Lecture

Quasi-Periodic Materials – A Paradigm Shift in Crystallography

Presentation

Nobel Lecture

Dan Shechtman delivered his Nobel Lecture on 8 December 2011, at Aula Magna, Stockholm University, where he was introduced by Professor Lars Thelander, Chairman of the Nobel Committee for Chemistry.

Quasi-Periodic Materials – A Paradigm Shift in Crystallography: Lecture slides

Pdf 5.8 MB

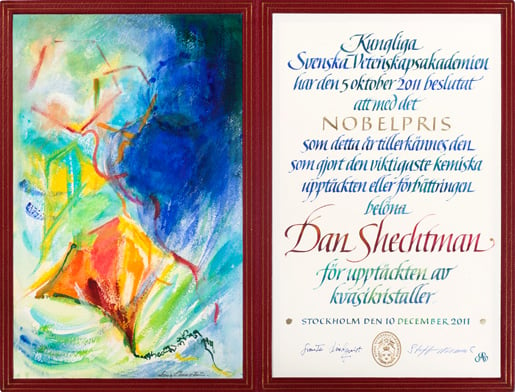

Dan Shechtman – Nobel diploma

Copyright © The Nobel Foundation 2011

Artist: Lena Cronström

Calligrapher: Annika Rücker

Book binder: Ingemar Dackéus

Photo reproduction: Lovisa Engblom

Dan Shechtman – Banquet speech

Dan Shechtman’s speech at the Nobel Banquet in the Stockholm City Hall, 10 December 2011.

Your Majesties, Your Royal Highnesses, Nobel Laureates, fellow scientists, ladies and gentlemen, dear family.

On April 8, 1982, I was alone in the electron microscope room when I discovered the Icosahedral Phase that opened the field of quasi–periodic crystals. However, today I am joined by many hundreds of enthusiastic scientists worldwide. I stand here as the vanguard of the science of quasicrystals, but without these dedicated scientists the field would not be where it is today. This supreme recognition of the science we have unveiled over the last quarter century is celebrated by us all.

In the beginning there were only a handful of gifted colleagues who helped launch the field. First was Ilan Blech, at the time a Technion professor, who proposed the first icosahedral model. He demonstrated, by computer simulation, that the model could produce diffraction patterns that matched those that I had observed in the electron microscope. Together we wrote the first announcement of the discovery. Then John Cahn of the US and Denis Gratias of France coauthored with us the second, modified article that was actually published first. Other key contributions to the field were made by Roger Penrose of the UK who, years earlier, created a nonrepeating aperiodic mosaic with just two rhomboid tiles, and Alan Mackay of the UK who showed that Penrose tiles produce sharp diffraction spots. Dov Levine of Israel and Paul Steinhardt of the US made the connection between my diffraction patterns and Mackay’s work. They published a theoretical paper formulating the fundamentals of quasi-crystals and coined the term. All these pioneers paved the way to the wonderful world of quasi-periodic materials.

I would like to mention two other eminent scientists who are no longer with us, whose commitment to the field was of great importance. These are Luis Michel, a prominent French mathematician, and Kehsin Kuo of China, a leader in electron microscopy, who was trained in Sweden.

We are now approaching the end of 2011, the UNESCO International Year of Chemistry, a worldwide celebration of the field. In a few weeks we will see in the New Year, 2012, the centennial of the von Laue experiment which launched the field of modern crystallography. The following year, 2013, will mark the International Year of Crystallography. The paramount recognition of the discovery of quasi-periodic crystals is, therefore, most timely.

The discovery and the ensuing progress in the field resulted in a paradigm shift in the science of crystallography. A new definition of crystal emerged, one that is beautiful and humble and open to further discoveries. A humble scientist is a good scientist.

Science is the ultimate tool to reveal the laws of nature and the one word written on its banner is TRUTH. The laws of nature are neither good nor bad. It is the way in which we apply them to our world that makes the difference.

It is therefore our duty as scientists to promote education, rational thinking and tolerance. We should also encourage our educated youth to become technological entrepreneurs. Those countries that nurture this knowhow will survive future financial and social crises. Let us advance science to create a better world for all.

———

I would like to thank the scientists who nominated me, the Nobel Committee, the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences and the Nobel Foundation for bestowing on me this unparalleled honor.

Thank you.

Dan Shechtman – Prize presentation

Watch a video clip of the 2011 Nobel Laureate in Chemistry, Dan Shechtman, receiving his Nobel Prize medal and diploma during the Nobel Prize Award Ceremony at the Concert Hall in Stockholm, Sweden, on 10 December 2011.

Press release

English

English (pdf)

Swedish

Swedish (pdf)

5 October 2011

The Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences has decided to award the Nobel Prize in Chemistry for 2011 to

Dan Shechtman

Technion – Israel Institute of Technology, Haifa, Israel

“for the discovery of quasicrystals”

A remarkable mosaic of atoms

In quasicrystals, we find the fascinating mosaics of the Arabic world reproduced at the level of atoms: regular patterns that never repeat themselves. However, the configuration found in quasicrystals was considered impossible, and Dan Shechtman had to fight a fierce battle against established science. The Nobel Prize in Chemistry 2011 has fundamentally altered how chemists conceive of solid matter.

On the morning of 8 April 1982, an image counter to the laws of nature appeared in Dan Shechtman’s electron microscope. In all solid matter, atoms were believed to be packed inside crystals in symmetrical patterns that were repeated periodically over and over again. For scientists, this repetition was required in order to obtain a crystal.

Shechtman’s image, however, showed that the atoms in his crystal were packed in a pattern that could not be repeated. Such a pattern was considered just as impossible as creating a football using only six-cornered polygons, when a sphere needs both five- and six-cornered polygons. His discovery was extremely controversial. In the course of defending his findings, he was asked to leave his research group. However, his battle eventually forced scientists to reconsider their conception of the very nature of matter.

Aperiodic mosaics, such as those found in the medieval Islamic mosaics of the Alhambra Palace in Spain and the Darb-i Imam Shrine in Iran, have helped scientists understand what quasicrystals look like at the atomic level. In those mosaics, as in quasicrystals, the patterns are regular – they follow mathematical rules – but they never repeat themselves.

When scientists describe Shechtman’s quasicrystals, they use a concept that comes from mathematics and art: the golden ratio. This number had already caught the interest of mathematicians in Ancient Greece, as it often appeared in geometry. In quasicrystals, for instance, the ratio of various distances between atoms is related to the golden mean.

Following Shechtman’s discovery, scientists have produced other kinds of quasicrystals in the lab and discovered naturally occurring quasicrystals in mineral samples from a Russian river. A Swedish company has also found quasicrystals in a certain form of steel, where the crystals reinforce the material like armor. Scientists are currently experimenting with using quasicrystals in different products such as frying pans and diesel engines.

| Read more about this year’s prize |

| Information for the Public Pdf 3 MB |

| Scientific Background Pdf 1,3 MB |

| Links and Further Reading |

Dan Shechtman, Israeli citizen. Born 1941 in Tel Aviv, Israel. Ph.D. 1972 from Technion – Israel Institute of Technology, Haifa, Israel. Distinguished Professor, The Philip Tobias Chair, Technion – Israel Institute of Technology, Haifa, Israel.

http://materials.technion.ac.il/shechtman.html

The Prize amount: SEK 10 million

Contacts: Erik Huss, Press Officer, phone +46 8 673 95 44, +46 70 673 96 50, [email protected]

Ann Fernholm, Editor, Phone +46 70 750 22 16, [email protected]

The Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences, founded in 1739, is an independent organization whose overall objective is to promote the sciences and strengthen their influence in society. The Academy takes special responsibility for the natural sciences and mathematics, but endeavours to promote the exchange of ideas between various disciplins.

Useful Links / Further Reading

| Websites |

| Shechtman, D., Technion – Israel Institute of Technology, http://materials.technion.ac.il/shechtman.html |

| Lifshitz, R., Introduction to quasicrystals, http://www.tau.ac.il/~ronlif/quasicrystals.html |

| Interviews and lectures (video and slide show) |

| Shechtman, D. (2010) Quasicrystals, a new form of matter, http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=EZRTzOMHQ4s |

| Senechal, M. (2011) Quasicrystals gifts to mathematics, http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=pjao3H4z7-g&feature=relmfu |

| Steurer, W. (2011) Fascinating quasicrystals, http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jM4AIipGOdk |

| Steinhardt, P.J., What are quasicrystals?, http://www.physics.princeton.edu/~steinh/QuasiIntro.ppt |

| Popular science articles |

| Shtull-Trauring, A. (2011) Clear as crystal, Haaretz, http://www.haaretz.com/weekend/magazine/clear-as-crystal-1.353504 |

| Scientific American, http://www.scientificamerican.com, search for quasicrystals. |

| Books |

| Hargittai, B. and Hargittai, I. (2005) Candid Science V: Conversations with Famous Scientists, Imperial College Press, London. |

| Original article |

| Shechtman, D., Blech, I., Gratias, D., and Cahn, J.W. (1984) Metallic phase with long-range orientational order and no translational symmetry, Phys. Rev. Lett. 53(20):1951-1954. |

Pressmeddelande: Nobelpriset i kemi 2011

English

English (pdf)

Swedish

Swedish (pdf)

5 oktober 2011

Kungl. Vetenskapsakademien har beslutat utdela Nobelpriset i kemi år 2011 till

Dan Shechtman

Technion – Israel Institute of Technology, Haifa, Israel

“för upptäckten av kvasikristaller”

Märklig mosaik i materiens inre

I kvasikristaller återfinns arabvärldens fascinerande mosaiker på atomnivå: regelbundna mönster som aldrig upprepar sig. Upptäckten av kvasikristaller stred mot all logik, och Dan Shechtman förde en tuff kamp mot den etablerade vetenskapen. 2011 års Nobelpris i kemi har fått kemister att i grunden ändra sin syn på fasta material.

På morgonen den 8 april 1982 gav Dan Shechtmans elektronmikroskop en bild som stred mot naturlagarna. Enligt dåtidens syn på fasta material packade sig atomer inuti kristaller i symmetriska mönster som upprepade sig periodiskt, om och om igen. Upprepning var en förutsättning för att få en kristall, menade forskarna.

Men Dan Shechtmans experiment visade att atommönstret i kristallen framför honom absolut inte kunde upprepas. Det var ungefär lika ologiskt som om han hade hittat en fotboll gjord av bara sexhörningar (en sfär kräver både fem- och sexhörningar). Därför blev upptäckten enormt kontroversiell. När Dan Shechtman argumenterade för den blev han till och med ombedd att lämna sin forskargrupp. Men hans kamp har lett till att forskarvärlden har fått ändra sin syn på materiens innersta.

Så kallade aperiodiska mosaiker, liknande de som pryder medeltida arabiska byggnadsverk som templet Alhambra i Spanien och helgedomen Darb-i Imam i Iran, har hjälpt forskare att förstå hur kvasikristaller ser ut på atomnivå. I aperiodiska mosaiker och i kvasikristaller är mönstren regelbundna – de följer matematiska regler – men de upprepar sig aldrig.

När forskare räknar på Shechtmans kvasikristaller behöver de använda det gyllene snittet inom matematiken och konsten. Detta tal intresserade redan matematiker i antikens Grekland eftersom det ofta dök upp inom geometrin. I kvasikristaller är till exempel kvoten mellan olika atomavstånd relaterad till det gyllene snittet.

Efter Shechtmans upptäckt har forskare tagit fram andra former av kvasikristaller och nyligen hittade de naturliga kvasikristaller i mineralprover från en rysk flod. Ett svenskt företag har också funnit kvasikristaller i ett av sina stål, där de fungerar som en slags armering. Forskare experimenterar med att använda kvasikristaller i allt från stekpannor till dieselmotorer.

| Läs mer om årets kemipris |

| Populärvetenskaplig information Pdf 3 MB |

| Scientific Background Pdf 1,3 MB |

| Länkar och lästips |

Dan Shechtman, israelisk medborgare. Född 1941 (70 år) i Tel Aviv, Israel. Fil.dr 1972 vid Technion – Israel Institute of Technology, Haifa, Israel. Distinguished Professor, The Philip Tobias Chair vid Technion – Israel Institute of Technology, Haifa, Israel.

http://materials.technion.ac.il/shechtman.html

Prissumma: 10 miljoner svenska kronor

Kontaktpersoner: Erik Huss, pressansvarig, tel. 08-673 95 44, 070-673 96 50, [email protected]

Ann Fernholm, redaktör, tel. 070-750 22 16, [email protected]

Kungl. Vetenskapsakademien, stiftad år 1739, är en oberoende organisation som har till uppgift att främja vetenskaperna och stärka deras inflytande i samhället. Akademien tar särskilt ansvar för naturvetenskap och matematik, men strävar efter att öka utbytet mellan olika discipliner.