Pär Lagerkvist – Photo gallery

1 (of 2) Pär Lagerkvist after receiving his Nobel Prize from Sweden’s King Gustaf VI Adolf at the award ceremony in Stockholm, Sweden, on 10 December 1951.

Scanpix, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

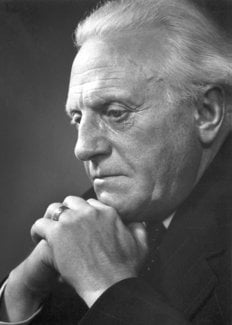

2 (of 2) Pär Lagerkvist ca 1951.

Photographer unknown (Svenska Dagbladet), Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Pär Lagerkvist – Bibliography

| Works in Swedish |

| Människor. – Stockholm : Fram, 1912 |

| Ordkonst och bildkonst : om modärn skönlitteraturs dekadans : om den modärna konstens vitalitet. – Stockholm : Bröderna Lagerströms, 1913 |

| Två sagor om livet. – Stockholm : Fram, 1913 |

| Motiv. – Stockholm : Bonnier, 1914 |

| Järn och människor. – Stockholm : Bonnier, 1915 |

| Ångest. – Stockholm : Bonnier, 1916 |

| Sista mänskan. – Stockholm : Bonnier, 1917 |

| Teater : Den svåra stunden, tre enaktare : Modern teater, Synpunkter och angrepp. – Stockholm : Bonnier, 1918 |

| Kaos. – Stockholm : Bonnier, 1919 |

| Det eviga leendet. – Stockholm : Bonnier, 1920 |

| Den lyckligas väg. – Stockholm : Bonnier, 1921 |

| Den osynlige. – Stockholm : Bonnier, 1923 |

| Onda sagor. – Stockholm : Bonnier, 1924 |

| Gäst hos verkligheten. – Stockholm : Bonnier, 1925 |

| Hjärtats sånger. – Stockholm : Bonnier, 1926 |

| Det besegrade livet. – Stockholm : Bonnier, 1927 |

| Han som fick leva om sitt liv. – Stockholm : Bonnier, 1928 |

| Kämpande ande. – Stockholm : Bonnier, 1930 |

| Konungen. – Stockholm : Bonnier, 1932 |

| Vid lägereld. – Stockholm : Bonnier, 1932 |

| Bödeln. – Stockholm : Bonnier, 1933 |

| Den knutna näven. – Stockholm : Bonnier, 1934 |

| I den tiden. – Stockholm : Bonnier, 1935 |

| Mannen utan själ. – Stockholm : Bonnier, 1936 |

| Genius. – Stockholm : Bonnier, 1937 |

| Den befriade människan. – Stockholm : Bonnier, 1939 |

| Seger i mörker. – Stockholm : Bonnier, 1939 |

| Sång och strid. – Stockholm : Bonnier, 1940 |

| Verner von Heidenstam : inträdestal i Svenska akademien den 20 december 1940. – Stockholm : Bonnier, 1940 |

| Dikter. – Stockholm : Bonnier, 1941 |

| Midsommardröm i fattighuset. – Stockholm : Bonnier, 1941 |

| Hemmet och stjärnan – Stockholm : Bonnier, 1942 |

| Dvärgen. – Stockholm : Bonnier, 1944 |

| De vises sten. – Stockholm : Bonnier, 1947 |

| Låt människan leva. – Stockholm : Bonnier, 1949 |

| Barabbas. – Stockholm : Bonnier, 1950 |

| Aftonland. – Stockholm : Bonnier, 1953 |

| Sibyllan. – Stockholm : Bonnier, 1956 |

| Ahasverus död. – Stockholm : Bonnier, 1960 |

| Pilgrim på havet. – Stockholm : Bonnier, 1962 |

| Det heliga landet. – Stockholm : Bonnier, 1964 |

| Valda Dikter. – Stockholm : Bonnier, 1965 |

| Mariamne. – Stockholm : Bonnier, 1967 |

| Den svåra resan. – Stockholm : Bonnier, 1985 |

| Major translations into English |

| The Eternal Smile and Other Stories / translated by Erik Mesterton and Denys W. Harding. – Cambridge, U.K. : Fraser, 1934 |

| Guest of Reality / translated by Erik Mesterton and Denys W. Harding. – London : Cape, 1936 |

| The Dwarf / translated by Alexandra Dick. – New York : Hill & Wang, 1945 |

| Barabbas / translated by Alan Blair. – New York : Random House, 1951 |

| Midsummer Dream in the Workhouse / translated by Alan Blair. – London : Hodge, 1953 |

| The Eternal Smile and Other Stories / translated by Alan Blair and others. – New York : Random House, 1954 |

| The Marriage Feast / translated by Alan Blair. – New York : Hill & Wang, 1954 |

| The Sibyl / translated by Naomi Walford. – New York : Random House, 1958 |

| The Death of Ahasuerus / translated by Naomi Walford. – New York : Random House, 1962 |

| Pilgrim at Sea / translated by Naomi Walford. – New York : Random House, 1964 |

| The Holy Land / translated by Naomi Walford. – New York : Random House, 1966 |

| Herod and Mariamne / translated by Naomi Walford. – New York : Knopf, 1968 |

| Evening Land / translated by W. H. Auden and Leif Sjöberg. – New York : Wayne State University Press, 1975 |

| Five Early Works / translated by Roy Arthur Swanson. – Lewiston, N.Y. : Edwin Mellen Press, 1988 |

| Guest of Reality / translated by Robin Fulton. – London : Quartet, 1989 |

| Critical studies (a selection of works in English) |

| Ryberg, Anders, Pär Lagerkvist in Translation : a Bibliography. – Stockholm : Bonnier, 1964 |

| Spector, Robert Donald, Pär Lagerkvist. – New York : Twayne, 1973 |

| White, Ray Lewis, Pär Lagerkvist in America. – Stockholm, 1979 |

The Swedish Academy, 2007

Pär Lagerkvist – Nominations

Pär Lagerkvist – Banquet speech

English

Swedish

Pär Lagerkvist’s speech at the Nobel Banquet at the City Hall in Stockholm, December 10, 1951 (in Swedish)

»Ers Majestät, Ers Kungliga Högheter, mina damer och herrar.

Jag ber att få varmt tacka Svenska Akademien för att den tilldelat mig årets Nobelpris i litteratur. Det är en så stor ära att man sannerligen har anledning fråga sig om man förtjänar den. Men jag har inte ens vågat göra mig den frågan. Som väl är har jag inte deltagit i beslutet och känner mig på det angenämaste sätt oansvarig. Ansvaret vilar helt på mina ärade kolleger – och det är jag också mycket tacksam för.

Här har nu ikväll hållits – och kommer att hållas – så många storartade tal. Jag ska därför inte hålla något. Jag ska istället be att få läsa ett stycke ur en bok av mig som aldrig blivit utgiven. Medan jag höll på och funderade över ett tal för detta högtidliga tillfälle inträffade nämligen något ganska egendomligt. Man fann ett gammalt manuskript av mig, skrivet 1922, alltså för 29 år sen. Jag läste det och fann då att partiet i början innehöll ungefär just det som jag hade tänkt försöka säga här – men i diktens form, som onekligen passar mig bättre. Det handlar om det gåtfulla i vårt väsen och i vår tillvaro, om detta som gör människans öde så stort – och så svårt.

Boken skrevs alltså för nära 30 år sen. Nere i en liten by i Pyrenéerna, åt Medelhavssidan, alltså i en mycket vacker del av jorden. Jag läser nu början på den – så gott jag kan.

Myten om människorna

Det var en gång en värld, till den kom en morgon två mänskor, men inte för att stanna där någon längre tid, blott för ett kort besök. De hade många andra världar också, denna tycktes dem oansenligare och fattigare än de. Det var vackert med träden och de stora drivande skyarna här, det var vackert med bergen, med skogen och lundarna, och med vinden som kom osynlig när det började skymma och rörde så hemlighetsfullt vid allt; men det var ingenting mot de världar de ägde långt borta. Därför ville de bara stanna en liten tid. Men en tid ville de gärna bli kvar, för de älskade varandra, och det var som om ingenstans deras kärlek blivit någonting så förunderligt som här. Det tycktes som om kärleken inte var någonting självfallet i denna värld, något som helt uppfyllde allt, men att den togs emot som en gäst av vilken man väntade sig det största som kunde ske här. Ja, det var som om allt det klaraste och ljusaste i deras väsen här blev så hemlighetsfullt, så dunkelt, beslöjat, som om det hölls dolt för dem. De var främlingar här, ensamma, överlämnade åt okända makter. Och kärleken som förenade dem var ett under, något som kunde förintas, som kunde förtvina och dö. Därför ville de stanna en liten tid här.

I denna värld var det inte alltid dag. Efter ljuset föll skymning över allting, det plånades ut, fanns inte mer. I mörkret låg de och lyssnade. De hörde vinden susa tungt i träden. De kröp samman inunder dem: varför lever vi här?

Mannen gjorde ett hus åt dem, bara av mossa och stenar, därför att de snart skulle bryta upp igen. Kvinnan bredde doftande gräs på det tilltrampade golvet och väntade honom när kvällen kom. De älskade varandra innerligare än de någonsin tyckte sig ha gjort, och skötte de värv som livet här lade på dem.

En dag när mannen strövade kring ute i markerna fick han en sådan längtan efter henne som han höll kär över allting. Då böjde han sig ner och kysste jorden, för att hon hade vilat på den. Men kvinnan började älska molnen och de stora träden, därför att mannen vände tillbaka hem inunder dem, och hon älskade skymningsstunden för att han kom då. Det var en främmande värld, den liknade inte dem de ägde långt borta.

Och kvinnan födde en son. Järnekarna utanför huset sjöng för honom, han såg sig förundrad omkring och somnade sen tryggt in av suset. Men mannen kom hem var kväll med blodiga djur, han var trött och lade sig tungt ner. I mörkret talade de lyckliga med varandra, nu skulle de snart bryta upp.

Hur underlig den var, denna värld; efter sommaren följde höst och en kylig vinter, efter vintern den ljuvligaste vår. På det kunde man se hur tiden flöt bort, allting var föränderligt här. Kvinnan födde igen en son, och efter några år ännu en. Barnen växte upp, de började syssla med sitt, sprang kring och lekte och fann nya ting var dag. De lekte med hela den märkliga världen, med allting i den. Det som var menat på fullaste allvar gjorde de till något som bara var menat för dem. Mannens händer blev grova av arbetet med jorden och av mödorna i skogen. Kvinnans drag började också hårdna och hon gick långsammare kring, men hennes röst var mjuk och sjungande som förr. En kväll när hon trött efter en lång dag hade satt sig till inne i skymningen, med barnen samlade kring sig, sade hon till dem: nu skall vi snart bryta upp härifrån, nu skall vi snart draga bort till de andra världar där vi har vårt hem. Barnen såg förundrade på henne. Vad säger du mor? Finns det andra världar än denna? Då möttes hennes och mannens blick, ett styng gick genom dem, en svidande smärta. Med lägre röst svarade hon: visst finns det andra världar än denna. Och hon började berätta. Hon berättade om dessa världar som var så olika den där de nu levde, där allting var så mycket underbarare och större än här, så ljust och lyckligt, där det inte var ett sådant mörker, där inga träd susade som här, där ingen kamp tyngde såsom denna. Barnen slöt sig lyssnande omkring henne, ibland såg de undrande bort på fadern som för att fråga om det var sant, han rörde jakande huvudet, försjunken i tankar. Den minste satt tätt intill moderns fötter, han var blek, hans ögon strålade med en sällsam glans. Men äldste sonen, som var tolv år gammal, satt längre ifrån, han tittade i marken, till slut reste han sig och gick ut i mörkret.

Modern fortsatte, de lyssnade och lyssnade, det var som om hon såg långt långt bort, hennes blick var frånvarande, ibland höll hon inne, alldeles som om hon inte kunde se, inte minnas något mer, som om hon hade glömt; så talade hon igen, med en stämma ännu mera avlägsen än förr. Elden flämtade på den sotiga härden, den lyste på deras ansikten, den kastade sitt sken kring i det upphettade rummet; fadern höll handen över ögonen, barnen lyddes med strålande blick. Så satt de kvar orörliga ända till inemot midnatt. Då öppnades dörren med en kall fläkt utifrån och den äldste sonen trädde in. Han såg sig omkring. I handen hade han en stor svart fågel med grå buk, ur bröstet rann blod, det var den första han själv hade nedlagt, han kastade den på marken bredvid elden, det rykte från det varma blodet, utan ett ord gick han längst in i halvdunklet och lade sig att sova.

Det blev alldeles tyst. Modern slutade. Förundrade såg de på varandra, som vaknade ur en dröm, förundrade såg de den blodiga fågeln, som fuktade marken röd omkring sitt bröst. De reste sig tigande och gick alla till vila.

Efter den kvällen talade de en tid inte mycket samman, gick var och en för sig. Det var på sommaren, humlorna surrade, gräsmarkerna frodades där runtomkring, lundarna grönskade efter vårregnet som hade fallit, luften stod så klar över allting. En dag kom den minste fram till modern som satt utanför huset vid middagstiden, han var blek och stilla, han bad att hon skulle berätta för honom om en annan värld. Modern såg förvånad upp. Kära, inte kan jag tala med dig om detta nu, solen står högt på himlen, varför leker du inte med allt som är ditt? Han gick tyst ifrån henne och grät utan att någon visste om det.

Sedan bad han aldrig mer om detta. Han blev bara blekare och blekare, ögonen brände med en främmande glans, en morgon måste han bli liggande, kunde inte resa sig upp. Där låg han orörlig dag efter dag, talade nästan inte, bara såg liksom långt bort med sin förstorade blick. De frågade honom om hans onda, de sade att snart skulle han kunna gå ut i solen igen, där hade nu kommit andra blommor än förut, större än då; han svarade inte, tycktes inte se dem. Modern vakade över honom och grät, hon frågade om han ville hon skulle berätta för honom allt det underbara hon visste, men han log och låg bara stilla som förut.

Och en kväll slöt han sina ögon och var död. De samlades alla kring honom. Modern lade hans små händer till rätta över bröstet. När sedan skymningen kom satt de tillhopa i det mörknade rummet och talade viskande om honom. Nu hade han lämnat denna världen. Nu var han inte mera här. Nu hade han gått till en annan värld, bättre och lyckligare än denna. Men de sade det beklämda, suckande tungt. Skygga gick de till vila längst borta från den döde, han låg ensam och kall.

På morgonen grävde de ner honom i jorden, han skulle ligga där. Markerna doftade, solen strålade milt och varmt överallt. Modern sade, han är inte här. Vid graven stod ett rosenträd som blommade nu.

Och åren gick. Modern satt ofta ute vid graven om aftnarna, stirrande bort över bergen som stängde in allt. Fadern stod där en stund när han hade sin väg förbi. Men barnen ville inte gå dit, för där var inte som annars på jorden.

Nu växte de bägge sönerna till, blev fullvuxna och resliga, fick något annat och frejdigare över sig än förut; men mannen och kvinnan vissnade bort. De grånade, böjdes, något vördnadsvärt och stillsamt kom över dem. Fadern sökte ännu följa sönerna på jakten, när villebrådet var farligt kämpade inte längre han utan de mot det. Men den åldrade modern satt utanför huset, hon kände sig för med handen när de kom emot henne om kvällen, hennes ögon var så trötta att hon bara såg vid middagstimman då solskenet var fullt, annars var det för mörkt, hon frågade dem: varför är det så mörkt här? En höst drog hon sig innanför huset, låg och lyssnade till vinden som till minnen från länge, länge sen. Mannen satt och höll hennes hand i sin, de talades vid om sitt, det var som om de åter var ensamma här. Hon tynade av, men hennes anlete blev som förklarat av ljus. Och hon sade en afton till dem alla med sin bräckliga röst: nu vill jag gå bort från denna världen där jag har levat, nu skall jag gå hem. Och hon gick därifrån. De grävde ner henne i jorden, hon skulle ligga där.

Så blev det igen vinter och köld, den gamle höll sig vid härden, orkade inte ut. Sönerna kom hem med djur, då styckade de tillsammans dem. Darrhänt vände han spettet och såg hur elden blev rödare när köttet stektes i den. Men då våren kom gick han ut i markerna, betraktade träden och ängarna som nu grönskade runt omkring. Han stannade vid de träden som han kände igen, han stannade överallt, allt kände han igen. Han stannade hos de blommor han plockat åt henne, som han älskade, den första morgonen då de kom hit. Han stannade hos sina redskap för jakten, som var blodiga för att en av sönerna hade tagit dem i bruk. Så gick han in i huset och lade sig ner, och han sade till sönerna som stod vid hans dödsläger: nu måste jag gå bort från denna världen där jag har levat mitt liv, nu måste jag lämna den. Vårt hem är inte här. Och han höll fast i deras händer ända tills han var död. De grävde ner honom i jorden, såsom han hade befallt, han ville ligga där.

Nu var de gamla döda. De unga kände en sådan underlig lättnad, befrielse, som om någonting klippts av. Det var som om livet befriats från något som inte hörde till det. De steg upp bittida om morgonen den dagen som följde, vilken lukt av de nyutslagna träden och av regnet som fallit på natten! Tillsammans drog de ut, sida vid sida, båda högresta och nyss unga, det var en glädje för jorden att bära dem. Nu började människolivet, de gick ut för att taga denna världen i besittning.»

Pär Lagerkvist – Banquet speech

English

Swedish

Pär Lagerkvist’s speech at the Nobel Banquet at the City Hall in Stockholm, December 10, 1951

(Translation)

I wish to express my warm thanks to the Swedish Academy for awarding me the Nobel Prize in Literature. This is so great an honour that one may be excused for asking oneself – have I really deserved it? Speaking for myself, I dare not even pose the question! Having taken no part in making this decision, however, I can enjoy it with a free conscience. The responsibility rests with my esteemed colleagues and for this, too, I am truly thankful!

We have heard great speeches today and will presently hear more. I shall therefore refrain from making one but will ask you instead to bear with me while I read you a passage from a book of mine that has never been published. I was wondering what I should say on this solemn occasion, when something rather strange happened; I unearthed an old manuscript dating back to 1922, twenty-nine years ago. As I read it, I came upon a passage which more or less expressed what I would have said in my speech, except that it did so in the form of a story, which is much better suited to my taste. It is about the enigma of our life which makes human destiny at once so great and so hard.

I wrote it nearly thirty years ago. I was staying at the time in a little place in the Pyrenees on the shores of the Mediterranean, a very lovely part of the world. I will now read you the first part of it as well as I can.

The Myth of Mankind

Once upon a time there was a world, and a man and a woman came to it on a fine morning, not to dwell there for any length of time, but just for a brief visit. They knew many other worlds, and this one seemed to them shabbier and poorer than those others. True, it was beautiful enough with its trees and mountains, its forests and copses, the skies above with ever-changing clouds and the wind which came softly at dusk and stirred everything so mysteriously. But, for all that, it was still a poor world compared to those they possessed far, far away. Thus they decided to remain here for only a short while, for they loved each other and it seemed as though nowhere else was their love so wonderful as in just this world. Here, love was not something one took for granted and that permeated everyone and everything, but was like a visitor from whom wondrous things were expected. Everything that had been clear and natural in their life became mysterious, sinister, and veiled. They were strangers abandoned to unknown powers. The love that united them was a marvel – it was perishable; it could fade away and die. So for a while they wished to remain in this new world they had found for themselves.

It was not always daylight here. After the light of day, dusk would fall upon all things, wiping out, obliterating them. The man and woman lay together in the darkness listening to the wind as it whispered in the trees. They drew closer to each other, asking: why are we here at all?

Then the man built a house for himself and the woman, a house of stones and moss, for were they not to move on shortly? The woman spread sweet-scented grass on the earthen floor and awaited him home at dusk. They loved each other more than ever and went about their daily chores.

One day, when the man was out in the fields, he felt a great longing come upon him for her whom he loved above all things. He bent down and kissed the earth she had lain upon. The woman began to love the trees and the clouds because her man walked under them when he came home to her, and she loved twilight too, for it was then that he returned to her. It was a strange new world, quite unlike those other worlds they owned far, far away.

And so the woman gave birth to a son. The oak trees outside the house sang to him, he looked about him with startled eyes and fell asleep lulled by the sound of the wind in the trees. But the man came home at night carrying gory carcasses of slain animals; he was weary and in need of rest. Lying in the darkness, the man and woman talked blissfully of how they would soon be moving on.

What a strange world this was; summer followed by autumn and frosty winter, winter followed by lovely spring. One could see time pass as one season released another; nothing ever stayed for long. The woman bore another son and, after a few years, yet another. The children grew up and went about their business; they ran and played and discovered new things every day. They had the whole of this wonderful world to play with and all that was in it. Nothing was too serious to be turned into a toy. The hands of the man became calloused with hard work in the fields and in the forest. The woman’s features became drawn and her steps less sprightly than before, but her voice was as soft and melodious as ever. One evening, as she sat down tired after a busy day, with the children gathered round her, she said to them, «Now we shall soon be moving from here. We will be going to the other worlds where our home is». The children looked amazed. «What are you saying, Mother? Are there any other worlds than this?» The mother’s eyes met the husband’s and pain pierced their hearts. Softly, she replied, «Of course there are other worlds», and she began to tell them of the worlds so unlike the one in which they were living, where everything was so much more spacious and wonderful, where there was no darkness, no singing trees, no struggle of any sort. The children sat huddled around her, listening to her story. Now and then, they would look up at their father as if asking, «Is this true, what Mother is telling us?» He only nodded and sat there deep in his own thoughts. The youngest son sat very close to his mother’s feet; his face was pale, his eyes shone with a strange light. The eldest boy, who was twelve, sat further away and stared out. Finally, he rose and went out into the darkness.

The mother went on with her story and the children listened avidly. She seemed to behold some far-off country with eyes that stared unseeing; from time to time she paused as though she could see no more, remember no more. After a while, though, she would resume her story in a voice that grew fainter and fainter. The fire was flickering in the sooty fireplace; it shone upon their faces and cast a glow over the warm room. The father held his hand over his eyes. And so they sat without stirring until midnight. Then the door opened; a gust of cold air invaded the room and the eldest son appeared. He was holding in his hand a large black bird with blood gushing from its breast. This was the first bird he had killed on his own. He threw it down by the fire where it reeked of warm blood. Then, still without uttering a word, he went into a dark corner of the room at the back and lay down to sleep.

All was quiet now; the mother had finished her story. They gazed bewildered at each other, as if waking from a dream, and stared at the bird as it lay there dead, the red blood seeping from its breast, staining the floor about it. All arose silently and went to bed.

After that night, little was said for a time; each one went his own way. It was summer, bumblebees were buzzing in the lush meadows, the copses had been washed a bright green colour by the soft rains of spring, and the air was crystal clear. One day, at noon, the smallest child came up to his mother as she was sitting outside the house. He was very pale and quiet and asked her to tell him about the other world. The mother looked at him in amazement. «Darling,» she said, «I cannot speak of it now. Look, the sun is shining! Why aren’t you out playing with your brothers? » He went quietly away and cried, but no one knew.

He never asked her again but only grew paler and paler, his eyes burning with a strange light. One morning, he could not get up at all, but just lay there. Day after day, he lay still, hardly saying a word, gazing into space with his strange eyes. They asked him where the pain was and promised that he would soon be out again in the sun and see all the fine new flowers that had come up. He did not reply, but only lay there not even seeming to see them. His mother watched over him and cried and asked him if she should tell him of all the wonderful things she knew, but he only smiled at her.

One night, he closed his eyes and died. They all gathered round him, his mother folded his small hands over his breast and, when the dusk fell, they sat huddled together in the darkening room and talked about him in whispers. He had left this world, they said, and gone to another world, a better and happier one, but they said it with heavy hearts and sighed. Finally, they all walked away frightened and confused, leaving him lying there, cold and forsaken.

In the morning, they buried him in the earth. The meadows were scented, the sun was shining softly, and there was gentle warmth everywhere. The mother said, «He is no longer here.» A rose tree near his grave burst into blossom.

And so the years came and went. The mother often sat by the grave in the afternoons, staring over the mountains that shut everything out. The father paused by the grave whenever he passed it on his way, but the children would not go near it, for it was like no other place on earth.

The two boys grew up into tall strapping lads, but the man and the woman began to shrink and fade away. Their hair turned grey, their shoulders stooped, and yet a kind of peace and dignity came upon them. The father still tried to go out hunting with his sons, but it was they who coped with the animals when they were wild and dangerous. The mother, aging, sat outside the house and groped about with her hands when she heard them returning home. Her eyes were so tired now that they could only see at noon when the sun was at its highest in the sky. At other times, all was darkness about her and she used to ask why that was so. One autumn day, she went inside and lay down, listening to the wind as to a memory of long long ago. The man sat by her side and, together, they talked about things as if they were alone in the world once more. She had grown very frail but an inner light illuminated her features. One night, she said to them in her failing voice, «Now I want to leave this world where I have spent my life and go to my home.» And so she went away. They buried her in the earth and there she lay.

Then it was winter once more and very cold. The old man no longer went out, but sat by the fire. The sons came home with carcasses and cut them up. The old man turned the meat on the spit and watched the fire turn a brighter red where the meat was roasting on it. When the spring came, he went out and looked at the trees and fields in all their greenery. He paused by each one and gave it a nod of recognition. Everything here was familiar to him. He stopped by the flowers he had picked for her he loved the first morning they had come here. He stopped by his hunting weapons, now covered with blood, for one of his sons had taken them. Then he walked back into the house and lay down and said to his sons as they stood by his deathbed, «Now I must depart from this world where I have lived all my life and leave it. Our home is not here». He held their hands in his until he died. They buried him in the earth as he had bid them do, for it was there he wished to lie.

Now both the old people were gone and the sons felt a wonderful relief. There was a sense of liberation as though a cord tying them to something which was no part of them had been severed. Early next morning, they arose and went out into the open, savouring the smell of young trees and of the rain which had fallen that night. Side by side they walked together, the two tall youngsters, and the earth was proud to bear them. Life was beginning for them and they were ready to take possession of this world.

Prior to the speech, Einar Löfstedt, Member of the Swedish Academy and the Royal Academy of Sciences, made the following comments: «Is there a secret link between science and poetry? Perhaps there is. An English writer has said: ‹Poetry is the impassioned expression which is in the countenance of all science.› Whether these words apply to every science is open to question, but they do voice a very deep truth. Great poetry, as well as great science, is a form of obsession. They both want to lift man out of himself and to seek the answer to his eternal questions. With a visionary’s strength and an ever deeper earnestness, you, Pär Lagerkvist, have sought to throw light on the problems of humanity in our time. Long before most, you have given expression to the Anguish occasioned by the threatening mechanization and barrenness of modern civilization. You have seen the human mind as a car, black and empty, roaring along in the dark through unknown towns to an unknown goal. But by degrees you have also heard the delicate flute of tendemess playing in the night, and you have seen The Eternal Smile in the life of humble folk when it is lived in love and trust. And in Barabbas, your recent great work, you have shown us man – torpid, uncertain, guilt-laden, like most of us – half unconsciously following the Unknown One who died to save mankind.

We offer you our thanks and congratulations and are happy to have been able to bestow on you, on the repeated recommendation from other countries, the honour of the Nobel Prize.»

Pär Lagerkvist – Other resources

Links to other sites

On Pär Lagerkvist from Pegasos Author’s Calendar

Pär Lagerkvist – Facts

Award ceremony speech

Presentation Speech by Anders Österling, Permanent Secretary of the Swedish Academy

In a youthful manifesto of 1913 entitled Ordkonst och bildkonst [Verbal Art and Pictorial Art], Pär Lagerkvist, whose name was then unknown, had the audacity to find fault with the decadence of the literature of his time which, according to him, did not answer the requirements of art. His essay contains declarations which in their far too categorial form border on truism, but which in the light of his later work take on another, more profound meaning. Thus the young writer declared, «The writer’s mission is to explain his time from an artist’s point of view and to express the thought and feeling of this time for us and generations to come.» Today we can affirm that Lagerkvist himself, as far as one can follow him in his ascent toward maturity and greatness, amply accomplished this goal.

Today we call attention to this Swedish writer, not to present him in a general fashion – which would indeed seem superfluous – but to render to his work and to his person the homage due to them. Our attention is drawn above all to the impassioned, unfaltering sincerity, the ardent, unwearying patience, that have been the living forces behind his work. By these purely spiritual qualities, Pär Lagerkvist should answer fairly well, at least as a type of creative mind, to what Nobel said in the Sibylline terms of his will: «in an idealistic sense». Undeniably he belongs to that group of writers who, boldly and directly, have dedicated themselves to the vital questions of humanity, and who have tirelessly returned to the fundamental problems of our existence, with all that is overwhelming and sorrowful. The era in which he lived, whose materials determined his vocation, was menaced by rising clouds and by the eruptions of catastrophes. It is on this sombre and chaotic scene that he began to fight; it is in this country without sun that he discovered the flame of his inspiration.

Lagerkvist, with a precocious instinct of the imagination, apprehended the approaching disaster so far in advance that he was the prophet of anguish in Nordic literature; but he is also one of the most vigilant guardians of the spirit’s sacred fire which threatens to be extinguished in the storm. A number of those listening to me surely recall the short story in Lagerkvist’s Onda Sagor (1924) [Evil Tales], in which one sees the child of ten, on a luminous spring day, walking with his father along the railroad track; they hear together the songs of the birds in the forest, and then, on their way back, in the dusk, they are suddenly surprised by the unknown noise which cleaves the air. «I had an obscure foreboding of what that meant; it was the anguish which was going to come, all the unknown, which Father did not know, and from which he could not protect me. Here is what this world will be, what this life will be for me, not like Father’s life in which everything was reassuring and well established. It was not a real world, not a real life. It was only something ablaze which rushed into the depths of obscurity, obscurity without end.» This childhood memory now appears to us as a symbol of the theme that dominates Pär Lagerkvist’s work; at the same time, one might say that it proves to us that his subsequent works are authentic and logically necessary.

It is impossible, with the short time at our disposal today, to examine all these works in turn. The important thing is that, while Pär Lagerkvist makes use of different genres, dramatic or lyric, epic or satiric, his way of grasping reality remains fundamentally the same. It does not matter in his case if the results are not always on a level with the intentions, for each work plays the role of a stone in an edifice he intends to build; each is a part of his mission, a mission that always bears on the same subject: the misery and grandeur of what is human, the slavery to which earthly life condemns us, and the heroic struggle of the spirit for its liberation. This is the theme in all the works we choose to recall at this time: Gäst hos verkligheten (1925) [Guest of Reality]; Hjärtats sånger (1926) [Songs from the Heart]; Han som fick leva om sitt liv (1928) [He Who Lived His Life Over Again]; Dvärgen (1944) [The Dwarfl]; Barabbas (1950). It is needless to cite others to give an idea of the scope of Lagerkvist’s inspirations and the power of his genius.

One of the foreign experts who, on the fiftieth anniversary of the Nobel Foundation, criticized the historic series of Nobel Prize laureates, gave as criteria two conditions which seemed equally indispensable to him: on the one hand the artistic value of the finished work, on the other its international reputation. Insofar as this last condition is concerned, it can immediately be objected that those who write in a language that is not widespread will find themselves at a great disadvantage. In any case, it is extremely rare that a Nordic writer could make a reputation with the international public, and, therefore, a fair judgment on this kind of candidate is an especially delicate matter. However, Nobel’s will explicitly prescribes that the Prizes should be awarded«without any consideration of nationality, so that they should be awarded to the worthiest, be he Scandinavian or not.» That should also signify that if a writer seems worthy of the Nobel Prize, the fact that he is Swedish, for example, should not in the end hinder him from obtaining it. As for Pär Lagerkvist, we must consider another factor, which pleases us very much: his last work has attracted much sympathy and esteem outside our frontiers. This was further proved by the insistent recommendations with which Lagerkvist’s candidacy has been sustained by a majority of foreign advisers. He does not owe his Prize to the Academy circle itself. That the moving interpretations of the inner conflicts of Barabbas have found such repercussions even in foreign languages clearly shows the profoundly inspired character of this work, which is all the more remarkable as the style of it is original and in a sense untranslatable. Indeed, in this language at once harsh and sensitive, Lagerkvist’s compatriots often hear the echo of Småland folklore reechoing under the starry vault of Biblical legend. This reminds us once more that regional individuality can sometimes be transformed into something universal and accessible to all.

On each page of Pär Lagerkvist’s work are words and ideas which, in their profound and fearful tenderness, carry at the very heart of their purity a message of terror. Their origin is in a simple, rustic life, laborious and frugal of words. But these words, these thoughts, handled by a master, have been placed at the service of other designs and have been given a greater purpose, that of raising to the level of art an interpretation of the time, the world, and man’s eternal condition. That is why in the statement of the reasons for awarding the Nobel Prize to Pär Lagerkvist, it seems legitimate to us to affirm that this national literary production has risen to the European level.

Dr. Lagerkvist – We who have followed you from close by know how repugnant it is to you to be placed in the limelight. But since that seems inevitable at this moment, I beg you only to believe in the sincerity of our congratulations at the moment when you receive this award which, according to us, you have deserved more than any other at the present time. I have been obliged to sing your praises in front of you. But if the occasion were less solemn, I would be tempted to tell you quite simply, in the old Swedish manner: may it bring you happiness.

And now, it remains for me to ask you to receive from the hands of our King the Nobel Prize in Literature for 1951.

The Nobel Prize in Literature 1951

Pär Lagerkvist – Biographical

Pär Lagerkvist (1891-1974), son of station master Anders Johan Lagerkvist and Johanna Blad, was born in the south of Sweden. He decided early that he was going to be a writer and, after a year at the University of Uppsala, he left for Paris (1913), where he came under the influence of expressionism, especially in painting. His impressions resulted in the programmatic Ordkonst och bildkonst (1913) [Verbal Art and Pictorial Art]. Until 1930 Lagerkvist lived chiefly in France and Italy, and even after his permanent return to Sweden he frequently travelled on the Continent and in the Mediterranean.

Lagerkvist has given an account of his early years in the autobiographical volumes Gäst hos verkligheten (1925) [Guest of Reality] and Det besegrade livet (1927) [The Conquered Life]. His poetry moves from the anxiety and despair of the war years, as in Ångest (1916) [Anguish], to the celebration of love as a «universal conciliatory power», as in Hjärtats sånger (1926) [Songs from the Heart].

As a playwright, Lagerkvist has been extremely versatile. While Den svåra stunden (1918) [The Difficult Hour I, II, III] shows the influence of the later Strindberg, plays like Himlens Hemlighet (1919) [The Secret of Heaven] echo Tagore and the mystery play; Han som fick leva om sitt liv (1928) [He Who Lived His Life Over Again], on the other hand, is realistic. His work during the thirties was determined by his violent opposition to totalitarianism: Bödeln (1933) [The Hangman], Mannen utan själ (1936) [The Man without a Soul], and Seger i mörker (1939) [Victory in the Darkness].

Lagerkvist increasingly has dealt with the problem of man’s relation to God, particularly in his three important novels, Dvärgen (1944) [The Dwarf], Barabbas (1950), and Sibyllan (1956) [The Sibyl]. Barabbas, the story of a «believer without faith», was his first truly international success.

In 1940, Lagerkvist was elected to the Swedish Academy.

This autobiography/biography was written at the time of the award and first published in the book series Les Prix Nobel. It was later edited and republished in Nobel Lectures. To cite this document, always state the source as shown above.

Pär Lagerkvist died on July 11, 1974.