Miguel Angel Asturias – Nominations

Miguel Angel Asturias – Bibliography

| Works in Spanish |

| Sociologia guatemalteca : El problema social del indio. – Guatemala City Sánchez y de Guise, 1923 |

| Rayito de estrella. – Paris : Imprimerie Française de l’Edition, 1925 |

| La arquitectura de la vida nueva. – Guatemala City Goubaud, 1928 |

| La barba provisoria. – Havana, 1929 |

| Leyendas de Guatemala. – Madrid : Oriente, 1930 |

| Émulo Lipolidón, fantomima. – Guatemala City : Américana, 1935 |

| Sonetos. – Guatemala City : Américana, 1936 |

| Alclasán, fantomima. – Guatemala City : Américana, 1940 |

| Con el rehén en los diente : Canto a Francia. – Guatemala City : Zadik, 1942 |

| El Señor Presidente. – Mexico City : Costa-Amic, 1946 |

| Poesía : Sien de alondra. – Buenos Aires : Argos, 1949 |

| Hombres de maíz. – Buenos Aires : Losada, 1949 |

| Viento fuerte. – Buenos Aires : Ministerio de Educación Pública, 1950 |

| Ejercicios poéticos en forma de sonetos sobre temas de Horacio. – Buenos Aires : Botella al Mar, 1951 |

| Alto es el Sur : Canto a la Argentina. – La Plata, Argentina : Talleres gráficos Moreno, 1952 |

| Carta aérea a mis amigos de América. – Buenos Aires, 1952 |

| El papa verde. – Buenos Aires : Losada, 1954 |

| Bolívar : Canto al Libertador. – San Salvador : Ministerio de Cultura, 1955 |

| Soluna : Comedia prodigiosa en dos jornadas y un final. – Buenos Aires : Losange, 1955 |

| Obras escogidas. – Madrid : Aguilar, 1955-1966. – 3 vol |

| Week-end en Guatemala. – Buenos Aires : Losada, 1956 |

| La audiencia de los confines. – Buenos Aires : Ariadna, 1957 |

| Los ojos de los enterrados. – Buenos Aires : Losada, 1960 |

| El alhajadito. – Buenos Aires : Goyanarte, 1961 |

| Mulata de tal. – Buenos Aires : Losada, 1963 |

| Rumania, su nueva imagen. – Xalapa, Mexico : Universidad Veracruzana, 1964 |

| Teatro : Chantaje, Dique seco, Soluna, La audiencia de los confines. – Buenos Aires : Losada, 1964 |

| Clarivigilia primaveral. – Buenos Aires : Losada, 1965 |

| El espejo de Lida Sal. – Mexico City : Siglo Veintiuno, 1967 |

| Latinoamérica y otros ensayos. – Madrid : Guadiana, 1968 |

| Obras completas. – Madrid : Aguilar, 1968. – 3 vol. |

| Comiendo en Hungría / Miguel Angel Asturias, Pablo Neruda. – Barcelona : Lumen, 1969 |

| Maladrón. – Buenos Aires : Losada, 1969 |

| Tres de cuatro soles. – Madrid : Closas-Orcoyen, 1971 |

| El problema social del indio y otros textos / recogidos y presentados por Claude Couffon. – Paris : Centre de Recherches de l’Institut d’Etudes Hispaniques, 1971 |

| Novelas y cuentos de juventud. – Paris : Centre de Recherches de I’Institut d’Etudes Hispaniques, 1971 |

| Torotumbo; La audiencia de los confines; Mensajes indios. – Barcelona: Plaza & Janés, 1971 |

| América, fábula de fábulas y otros ensayo / compilados con prólogo por Richard Callan. – Caracas: Monte Ávila, 1972 |

| Viernes de dolores. – Buenos Aires : Losada, 1972 |

| Mi mejor obra : Autoantología. – Mexico City : Organización Editorial Novaro, 1973 |

| Tres de cuatro soles / introducción y notas, Dorita Nouhaud. . – Ed. Crítica. – Madrid : Fondo de Cultura Económica, 1977 |

| El Señor Presidente. – Ed. Crítica / texto establecido por Ricardo Navas Ruiz, Jean-Marie Saint-Lu. – Paris : Klincksieck, 1978 |

| Viernes de dolores / texto establecido por Iber H. Verdugo. – Ed. Crítica. – Paris : Klincksieck, 1978 |

| Sinceridades / recopilado por Epaminondas Quintana. – Guatemala City : Académica Centroamericana, 1980 |

| Hombres de maíz / texto establecido por Gerald Martin. – Ed. Crítica. – Madrid : Fondo de Cultura Económica, 1981 |

| El hombre que lo tenía todo, todo, todo; La leyenda del Sombrerón; La leyenda del tesoro del Lugar Florido. – Barcelona: Bruguera, 1981 |

| Viajes, ensayos y fantasías / Compilación y prólogo Richard J. Callan . – Buenos Aires : Losada, 1981 |

| París 1924-1933 : periodismo y creación literaria / ed. crítica Amos Segala, coord. – Nanterre: ALLCA XX, 1988 |

| Cartas de amor, entre M. A. Asturias y Blanca de Mora y Araujo (1948-1954) : homenaje a Miguel Angel Asturias. – Madrid : Cultura Hispánica, 1989 |

| El árbol de la cruz. – Nanterre : ALLCA XX/Université Paris X, Centre de Recherches Latino-Américanes, 1993 |

| Con la magia de los tiempos. – Guatemala City : Ministerio de Cultura y Deportes, 1999 |

| Miguel Ángel Asturias, raíz y destino : Poesía inédita, 1917-1924 / Marco Vinicio Mejía, ed. – Guatemala City : Artemis Edinter, 1999 |

| Cuentos y leyendas. – Ed. Crítica / Mario Roberto, coordinador. – Madrid : ALLCA XX, 2000 |

| El señor presidente : edición crítica. – Ed. del centenario / Gerald Martin, coordinador. – Madrid : Allca, 2000 |

| Translations into English |

| The Mulatta and Mr. Fly / translated by Gregory Rabassa. – London : Owen, 1963 |

| The President / translated by Frances Partridge. – London: Gollancz, 1963. – Translation republished as El Señor Presidente. – New York : Atheneum, 1963 |

| Cyclone / translated by Darwin Flakoll and Claribel Alegría. – London : Owen, 1967 |

| Strong Wind / translated by Gregory Rabassa. – New York : Delacorte, 1968 |

| Sentimental Journey around the Hungarian Cuisine / translated by Barna Balogh. – Budapest : Corvina, 1969 |

| The Bejeweled Boy / translated by Martin Shuttleworth. – Garden City, N.Y.: Doubleday, 1971 |

| The Green Pope / translated by Gregory Rabassa. – New York : Delacorte, 1971 |

| The Talking Machine / translated by Beverly Koch. – Garden City, N.Y. : Doubleday, 1971 |

| The Eyes of the Interred / translated by Gregory Rabassa. – New York : Delacorte, 1973 |

| Men of Maize / translated by Gerald Martin. – New York : Delacorte/Seymour Lawrence, 1975 |

| Guatemalan Sociology : The Social Problem of the Indian / translated by Maureen Ahern. – Tempe : Arizona State University Center for Latin American Studies, 1977 |

| The Mirror of Lida Sal : Tales Based on Mayan Myths and Guatemalan Legends / translated by Gilbert Alter-Gilbert. – Pittsburgh : Latin American Literary Review, 1997 |

| Critical studies (a selection) |

| Prieto, René, Miguel Angel Asturias’s Archaeology of Return. – Cambridge, Eng.: Cambridge Univ. Press, 1993 |

| Llarena, Alicia, Realismo mágico y lo real maravilloso : Una cuestión de verosimilitud. – Gaithersburg, MD : Hispamérica, 1997 |

| Marting, Diane E, The Sexual Woman in Latin American Literature : Dangerous Desires. – Gainesville, L : Univ. Press of Florida, 2001 |

| Welly, Carina, Literarische Begegnungen mit dem Fremden : Intranationale und internationale Vermittlung kultureller Alterität am Beispiel des Erzählwerks Miguel Ángel Asturias’. – Würzburg : Königshausen & Neumann, 2004 |

The Swedish Academy, 2006

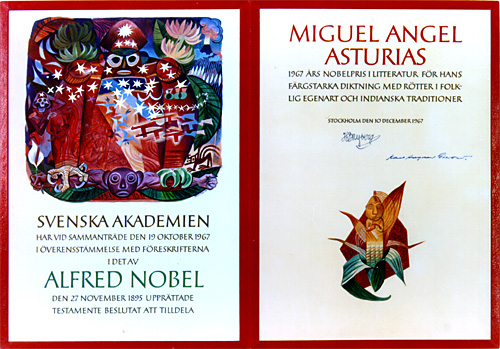

Miguel Angel Asturias – Nobel diploma

Copyright © The Nobel Foundation 1967

Artist: Gunnar Brusewitz

Calligrapher: Kerstin Anckers

Miguel Angel Asturias – Documentary

Credit: ITN Archive/Reuters

Miguel Angel Asturias – Banquet speech

English

Spanish

Miguel Angel Asturias’ speech at the Nobel Banquet at the City Hall in Stockholm, December 10, 1967

(Translation)

My voice on the threshold. My voice coming from afar. On the threshold of the Academy. It is difficult to become a member of a family. And it is easy. The stars know it. The families of luminous torches. To become a member of the Nobel family. To become an heir of Alfred Nobel. To blood ties, to civil relationship, a new consanguinity is added, a more subtle kinship, born of the spirit and the creative task. And this was perhaps the unspoken intention of the founder of this great family of Nobel Prize winners. To enlarge, through time, from generation to generation, the world of his own kin. As for me, I enter the Nobel family as the least worthy to be called among the many who could have been chosen.

I enter by the will of this Academy, whose doors open and close once a year in order to consecrate a writer, and also because of the use I made of the word in my poems and novels, the word which, more than beautiful, is responsible, a concern not foreign to that dreamer who with the passing of time would shock the world with his inventions – the discovery of the most destructive explosives then known – for helping man in his titanic chores of mining, digging tunnels, and constructing roads and canals.

I do not know if the comparison is too daring. But it is necessary. The use of destructive forces, the secret which Alfred Nobel extracted from nature, made possible in our America the most colossal enterprises. Among them, the Panama Canal. A magic of catastrophe which could be compared to the thrust of our novels, called upon to destroy unjust structures in order to make way for a new life. The secret mines of the people, buried under tons of misunderstanding, prejudices, and taboos, bring to light in our narrative – between fables and myths – with blows of protest, testimony, and denouncement, dikes of letters which, like sands, contain reality to let the dream flow free or, on the contrary, contain the dream to let reality escape.

Cataclysms which engendered a geography of madness, terrifying traumas, such as the Conquest: these cannot be the antecedents of a literature of cheap compromise; and, thus, our novels appear to Europeans as illogical or aberrant. They are not shocking for the sake of shock effects. It is just that what happened to us was shocking. Continents submerged in the sea, races castrated as they surged to independence, and the fragmentation of the New World. As the antecedents of a literature these are already tragic. And from there we have had to extract not the man of defeat, but the man of hope, that blind creature who wanders through our songs. We are peoples from worlds which have nothing like the orderly unfolding of European conflicts, always human in their dimensions. The dimensions of our conflicts in the past centuries have been catastrophic.

Scaffoldings. Ladders. New vocabularies. The primitive recitation of the texts. The rhapsodists. And later, once again, the broken trajectory. The new tongue. Long chains of words. Thought unchained. Until arriving, once again, after the bloodiest lexical battles, at one’s own expressions. There are no rules. They are invented. And after much invention, the grammarians come with their language-trimming shears. American Spanish is fine with me, but without the roughness. Grammar becomes an obsession. The risk of anti-grammar. And that is where we are now. The search for dynamic words. Another magic. The poet and the writer of the active word. Life. Its variations. Nothing prefabricated. Everything in ebullition. Not to write literature. Not to substitute words for things. To look for word-things, word-beings. And the problems of man, in addition. Evasion is impossible. Man. His problems. A continent that speaks. And which was heard in this Academy. Do not ask us for genealogies, schools, treatises. We bring you the probabilities of a word. Verify them. They are singular. Singular is the movement, the dialogue, the novelistic intrigue. And most singular of all, throughout the ages there has been no interruption in the constant creation.

Prior to the speech, Hugo Theorell, Professor at the Caroline Institute, made the following remarks: «One of our most competent literary critics has pointed out that this year’s Nobel Prize winner in Literature, Miguel Angel Asturias, in one of his most important books, El Senor Presidente, produces a strong effect by skilfully working with time and light – again our common ‹theme with variations›. Asturias paints in dark colours – against this background the rare light makes a so much stronger impression with his passionate, but artistically well balanced, protest against tyranny, injustice, slavery, and arbitrariness. He transforms glowing indignation into great literary art. This is indeed admirable.

May times come when conditions like those condemned by Mr. Asturias belong to history; when human beings live peacefully and happily together. This was indeed what Alfred Nobel hoped to promote by his Prizes.

Mr. Asturias – We sincerely admire your literary craftsmanship, and we hope that your work will contribute to ending the shameful social conditions that you have described with such impressive intensity. We congratulate you on your Nobel Prize, which you so very much deserve.»

Miguel Angel Asturias – Nobel Lecture

English

Nobel Lecture, 12th December 1967

(Translation)

The Latin American Novel

Testimony of an Epoch

I would have preferred this meeting to have been called a colloquium instead of lecture – a dialogue of doubts and assertions on the subject that concerns us. Let us start by analysing the antecedents of Latin American literature in general, focusing our attention on those aspects that have most connection with the novel. Let us follow the sources back to the millenarian origins of indigenous literature in its three great moments: Maya, Aztec and Inca.

The following question arises: Was there something resembling the novel among the indigenous peoples? I believe there was. The history of the original cultures of Latin America has more of what we in the western world call the novel than of history. It is necessary to bear in mind that the books of their history – their novels we would now say – were painted by the Aztecs and Mayas and preserved in a figurative form which we still do not understand by the Incas. This assumes the use of pictograms in which the voice of the reader – the indigenous do not distinguish between reading and reciting since for them it is the same thing – recited the text to the listeners in song form.

The reader, reciting stories or ‘great language’, the only person who understood what the pictograms meant, carried out an interpretation, recreating them for the enlightenment of those who listened. Later, these painted stories become fixed in the memory of the listeners and pass in oral form from generation to generation until the alphabet brought by the Spanish fixes them in their native tongues with Latin characters or directly in Spanish. In this way indigenous texts come to our knowledge with very little exposure to European corruption. The reading of these documents is what has allowed us to affirm that, among the native Americans, history has more of the characteristics of the novel than of history. They are accounts in which reality is dissolved in fable, legend, the trappings of beauty and in which the imagination, by dint of describing all the reality that it contains, ends up re-creating a reality that we might call surrealist.

This characteristic of the annulment of reality through imagination and the re-creation of a more transcendental reality is combined with a constant annulment of time and space as well as something more significant: the use and abuse of parallel expressions, i.e. the parallel use of different words to designate the same object, to convey the same idea and express the same feelings. I wish to draw attention to this point – the parallelism in the indigenous texts allows an exercise of nuances that we find hard to appreciate but which undoubtedly permitted a poetic gradation destined to induce certain states of consciousness which were taken to be magic.

If we return to the theme of the origin of a literary genre, similar to the novel, among the pre-Colombian peoples it is necessary to link the birth of this novel form with the epic. The heroic legend, exceeding the possibilities of historical fiction, was sung by the rhapsodists – the great voices of the tribes or ‘cuicanimes’ who toured the cities reciting the texts in order that the beauty of their songs would be disseminated among the peoples like the golden blood of their gods.

These epic songs that are so abundant in pre-Columbian literature, and so little known, possess what we call ‘fictional plot’ and what the Spanish friars and missionaries termed ‘tricks’.

These fictional tales were originally the testimony of past epochs; the memory and fame of high deeds that others on hearing would desire to emulate, this literature of reality and fable is broken in the instant of servitude and remains as one of the many broken vessels of those great civilisations. Other narratives will follow – in this same documentary form – recounting not the evidence of greatness but of misery, not the testimony of liberty but of slavery, no longer the statements of the masters but those of the subjects and a new, emerging American literature attempting to fill the empty silences of an epoch.

However, the literary genres that flourished in the Iberian peninsulas – the realistic novel and the theatre – were not to put down roots here. On the contrary, it is the indigenous effervescence, the sap and the blood, river, sea and mirage that affects the first Spaniard to write the first great American ‘novel’ for the ‘True Story of the Events of the Conquest of New Spain’ written by Bernal Diaz del Castillo deserves to be called no less. Is it not rather bold to describe as a ‘novel’ what that soldier called not history but ‘true history’? But are not novels frequently the true history? I repeat the question: is it really boldness to describe as a novel the work of this illustrious chronicler?

To those who might call me daring in my description I would invite them to enter the cadenced and panting prose of this versatile foot soldier and they will notice how – on entering into it – they gradually forget that what happened was reality and it will seem to them increasingly a work of pure imagination. Indeed, even Bernal himself says no less, next to the very walls of Tenochtitlan: “this seemed to be the work of enchantment that is recounted in the book of Amadis!” But this is the work of a Spaniard – it will be said – although the only thing Spanish about it is its having been written by a ‘peninsular’ resident in Santiago de los Caballeros de Guatemala – where that glorious manuscript is kept – and its having been composed in the old language of Castile although it partakes of that masquerade characteristic of indigenous literature. To Don Marcelino Menendez y Pelayo – this expert in classic Spanish literature – the taste of this prose is strange and the fact that it has been written by a soldier he finds surprising. It escapes this eminent writer that Bernal, at the age of eighty, had not only heard many texts of indigenous literature being recited, being influenced by it, but through osmosis had absorbed America and had already become American.

But there is another more impressive parenthesis. In their last sorrowful cantos the indigenous peoples – now subjugated – call for justice and Bernal Diaz Castillo expresses his deepest feelings in a chronicle which is a howl of protest at the oblivion into which they fell after being “fought and conquered.”

As from this moment, all Latin American literature, in song and novel, not only becomes a testimony for each epoch but also, as stated by the Venezuelan writer Arturo Uslar Pietri, an “instrument of struggle”. All the great literature is one of testimony and vindication, but far from being a cold dossier these are moving pages written by one conscious of his power to impress and convince.

Will the south give us a mestizo? The mestizo par excellence since – in order for nothing to be lacking – he was the first American exile: Inca Garcilaso. This Creole exile follows the indigenous voices already extinguished in his denunciation of the oppressors of Peru. The Inca offers us in his magnificent prose not only the native American – nor only the Spanish – but the mixture materialised in the fusion of the bloods, and in the same demand for life and justice.

To start with nobody discerns the ‘message’ in the prose of Inca. This will be clarified during the struggle for independence. Inca will then appear with the dignity of the Indian that knew how to make fun of the empire of “the two knives” – that is to say civil and ecclesiastical censorship. The Spanish authorities, slow to fathom the message containing so much spirit, imagination and melancholy, wisely order the confiscation of the story of Inca Garcilaso where the Indians have “learned so many dangerous things.”

Not only poetry and works of fiction bear witness. The least expected authors such as Francisco Javier Clavijero, Francisco Javier Alegre, Andres Calvo, Manuel Fabri, Andres de Guevara gave birth to a literature of exiles which is – and will continue to be – a testimony of its epoch.

Even the Guatemalan poet Rafael Landívar has his form of rebellion. His protest is silence – he calls the Spanish ‘Hispani’ without qualifying the adjective. We refer to Landívar because, despite being the least known, he should be considered the standard bearer of American literature as the authentic expression of our lands, our people and landscapes. According to Pedro Henriquez-Urena, “among the poets of the Spanish colonies he is the first master of landscape, the first to break definitively with the conventions of the Renaissance and discover the characteristic features of nature in the New World – its flora and fauna, its countryside and mountains, its lakes and waterfalls. In his descriptions of customs, of the crafts and the games there is an amusing vivacity and – throughout the poem – a deep sympathy and understanding of the survival of the original cultures.”

In 1781 in Modena, Italy, there appeared under the title of ‘Rusticatio Mexicana’ a poetic work of 3,425 Latin hexameters, in 10 cantos, written by Rafael Landívar. One year later in Bologna the second edition appeared. The poet called by Menendez y Pelayo ‘the Virgil of the modern age’ proclaimed to the Europeans the excellence of the land, the life and the peoples of America. He was concerned for the people of the Old World to know that E1 Jorullo, a Mexican volcano, could rival Vesuvius and Etna, that the waterfalls and caves of San Pedro Martir in Guatemala were the equals of the famous fountains of Castalia and Aretusa and referring to the cenzontle – the bird whose song has 400 tones – he elevated it above the realm of the nightingale.

He sings the praises of the countryside, of the gold and silver that was filling the world with valuable coins and the sugar loaves offered at royal tables.

His poem is not short of statistics concerning the riches of America. He cites the droves of cattle, the flocks of sheep, the herds of goats and pigs, the sources of medicinal waters, the popular games – some unknown in Europe – and he does not hide the glory of the cocoa and chocolate of Guatemala. But there is something that we should be aware of in the song of Landivar; namely his love of the indigenous. The Indian, for Landivar, is the race that succeeds in everything, he describes the marvels of the floating gardens created by the Indians, he holds them up as examples of charm and skill without forgetting their great sufferings. In this way he imparts poetic substance – in naturalistic poetry far from symbolism – to a fact that has always been denied: the superiority of the American Indian as farmer, as craftsman and worker.

To the image of the bad Indian, lazy and immoral that was so widely propagated in Europe and accepted in America by those who exploit it Landívar opposes the picture of the Indian on whose shoulders has weighed – and continues to weigh – the burden of labour in America. And he does not do it by simply stating it – in which case we would have the right or not of believing it. In his poem we see the Indian on board his charming canoe, transporting his goods or travelling and we admire him extracting the purple and scarlet, laying out the snowy worms that produce the silk, holding on stubbornly to the rocks in order to remove the beautiful shellfish, patiently and doggedly ploughing, cultivating the indigo plant, extracting the silver from his native mines, exhausting the golden veins… The Rusticatio of Landívar confirms what we have said of the great American literature – it cannot accept a passive role while on our soil a famished people live in these abundant lands. In its content it is a form of novel in verse.

Fifty years later, Andres Bello was to renovate the American adventure in his famous ‘Silva’, an immortal and perfect work in which the nature of the New World appears again with maize the leader – as haughty chief of the corn tribe – the cacao in ‘coral urns’, the coffee plants, the banana, the tropics in all their vegetable and animal power, contrasting the impoverished inhabitant with this grandiose vision ‘of the rich soil.’

Bello recalls Inca Garcilaso in his role as an exile, he is of the American lineage of Landívar, both represent the brilliant start of the great American odyssey in world literature. As from this moment the image of nature in the New World will awake in Europe an interest but it will never attain the incandescent fidelity that is achieved in the work of Landívar and Bello. A distorted vision of the marvels is offered us by Chateaubriand in ‘Atala’ and ‘Les Natchez’.

For the Europeans nature is a background without the gravitational force achieved by Creole romanticism. The romantics give nature a permanent presence in the creations of poets and novelists of the epoch. This is exemplified by José Maria de Heredia singing of the Niagara Falls and Estaban Echeverria describing the desert in ‘La Cautiva’ to mention just two.

Latin American romanticism was not only a literary school but a patriotic flag. Poets, historians and novelists divide their days and nights between political activities and dreaming their creations. Never has it been more beautiful to be a poet in America! Amongst the poets influenced by the Patria converted in Muse are José Mármol, author of one of the most widely read novels in Latin America – ‘Amalia’. The pages of this book have been turned by our febrile and sweaty fingers when we suffered in our very bones the dictatorships that have plagued Central America. The critics, when referring to the novel of Mármol, point out inconsistencies and carelessness without realising that a work of this type is written with a madly beating heart – pulsations that leave in the sentence, in the paragraph, on the page that abnormal heartbeat reflecting the distortion of the life force that troubled the entire country. We are in the presence of one of the most passionate examples of the American novel. Despite the years ‘Amelia’ – the imprecations of José, Mármol – continue to move readers to such an extent as to represent an act of faith.

It is at this very moment that the voice of Sarmiento is heard posing his famous dilemma at the threshold of the century: ‘civilisation or barbarism’. Indeed, Sarmiento himself will be startled when he becomes aware that ‘Facundo’ turns his arms against him and against everyone, declaring himself to be the authentic representative of Creole America, of the America that refuses to die and attempts to break – with a breast already hardened – the antithetical scheme of civilisation and barbarism in order to find between these two extremes the point where the American peoples are able to find their authentic personality with their own essential values.

In the middle of the last century another romantic, no less passionate, appears in Guatemala: José Batres Montúfar. In the midst of tales of festive character the reader feels that he should forget the fiesta to listen to the poetry. The immortal José Batres Montúfar, with abundant charm tinged with bitterness, was able to get to the core of issues that already – in the middle of the past century – were highly charged.

Another voice was to ring out from north to south, that of José Martí. His presence was felt, whether as an exile or in his beloved Cuba, the fre of his speech as poet or journalist being combined with the example of his sacrifice.

The 20th century is full of poets, poets that have nothing more to say with very few exceptions. Among the latter stand out the immortal Rubén Darío and Juan Ramón Molina from Honduras. The poets flee from reality, maybe because this is one of the ways of being a poet. But there is nothing living in much of their work which instead tend towards garrulity.

They are ignorant of the clear lesson of the native rhapsodists, they are forgetful of the colonial craftsmen of our great literature, satisfied with the bloodless imitation of the poetry of other latitudes and ridicule those who sang the bold gestures of the liberation struggle, considering them dazzled by a local patriotism.

It is only when the First World War is passed that a handful of men – men and artists – embark on the reconquest of their own tradition. In their encounter with the indigenous peoples they drop anchor in their Spanish home port and return with the message that they have to deliver to the future.

Latin American literature will be reborn under other signs – no longer that of verse. Now the prose is tactile, plural and irreverent in its attitude to conventions – to serve the purpose of this new crusade whose first move was to plunge into reality not so as to objectify but rather to penetrate the facts in order to identify fully with the problems of humanity. Nothing human – nothing which is real – will be foreign to this literature inspired by contact with America. And this is the case of the Latin American novel. Nobody doubts that the Latin American novel is at the leading edge of its genre in the world. It is cultivated in all our countries, by writers of different tendencies, which means that in the novel everything is forged from American material – the human witness of our historic moment.

We, the Latin American novelists of today, working within the tradition of engagement with our peoples which has enabled our great literature to develop – our poetry of substance – also have to reclaim lands for our dispossessed, mines for our exploited workers, to raise demands in favour of the masses who perish in the plantations, who are scorched by the sun in the banana fields, who turn into human bagasse in the sugar refineries. It is for this reason that – for me – the authentic Latin American novel is the call for all these things, it is the cry that echoes down the centuries and is pronounced in thousands of pages. A novel that is genuinely ours; determined and loyal – in its pages – to the cause of the human spirit, to the fists of our workers, to the sweat of our rural peasants, to the pain for our undernourished children; calling for the blood and the sap of our vast lands to run once more towards the seas to enrich our burgeoning new cities.

This novel shares – consciously or unconsciously – the characteristics of the indigenous texts; their freshness and power, the numismatic anguish in the eyes of the Creoles who awaited the dawn in the colonial night, more luminous however than this night that threatens us now. Above all, it is the affrmation of the optimism of those writers that defied the Inquisition, opening a breach in the conscience of the people for the march of the Liberators.

The Latin American novel, our novel, cannot betray the great spirit that has shaped – and continues to shape – all our great literature. If you write novels merely to entertain – then burn them! This might be the message delivered with evangelical fervour since if you do not burn them they will anyway be erased from the memory of the people where a poet or novelist should aspire to remain. Just consider how many writers there have been who – down the ages – have written novels to entertain! And who remembers them now? On the other hand, how easy it is to repeat the names of those amongst us who have written to bear witness.

To bear witness. The novelist bears witness like the apostle. Like Paul trying to escape, the writer is confronted with the pathetic reality of the world that surrounds him – the stark reality of our countries that overwhelms and blinds us and, throwing us to our knees, forces us to shout out: WHY DO YOU PERSECUTE ME? Yes, we are persecuted by this reality that we cannot deny, which is lived in the flesh by the people of the Mexican revolution, embodied in persons such as Mariano Azuela, Agustin Yanez and Juan Rulfo whose convictions are as sharp as a knife; those who share with Jorge Icaza, Ciro Alegría, Jesús Lara the shout of protest against the exploitation and abandonment of the Indian; those who with Romulo Gallegos in ‘Done Bábara’ create for us our Prometheus. Here is Horacio Quiroga who frees us from the nightmare of the tropics, a nightmare that is as peculiar to him as his style is American. ‘Los ros profundos’ of José María Arguedas, the ‘Rio oscuro’ of the Argentinian Alfredo Varela, ‘Hijo de hombre’ of the Paraguayan Roa Bastos and ‘La ciudad y los perros’ of the Peruvian Vargas Llosa make us see how the life-blood of the working people is drained in our lands.

Mancisidor takes us to the oil fields to which are drawn – leaving their homes – the inhabitants of ‘Cases muertas’ of Miguel Otero Silva… David Vinas confronts us with the tragic Patagonia, Enrique Wernicke sweeps us along with the waters that overwhelm whole communities while Verbitsky and María de Jesús lead us to the miserable shanty towns, the Dantesque and subhuman quarters of our great cities…

Teitelboim in ‘E1 hijo del salitre’ tells us of the gruelling work in the saltpetre mines while Nicomedes Guzman makes us share in the lives of the children in the Chilean working class districts. We feel the countryside of E1 Salvador in ‘Jaragua’ of Napoleón Rodríguez Ruiz and our small villages in ‘Cenizas del Izalco’ of Flakol and Clarivel Alegria. We cannot think of the pampas without speaking of ‘Don Segundo Sombra’ by Guiraldes nor speak of the jungle without ‘La voragine’ of Eustasio Rivera, nor of the Negroes: without Jorge Amado, nor of the Brazilian plains without the ‘Gran Sertao’ of Guimaraes Rosa, nor of the plains of Venezuela without Ramón Díaz Sánchez.

Our books do not search for a sensationalist or horrifying effect in order to secure a place for us in the republic of letters. We are human beings linked by blood, geography and life to those hundreds, thousands, millions of Latin Americans that suffer misery in our opulent and rich American continent. Our novels attempt to mobilise across the world the moral forces that have to help us defend those people. The mestizo process was already advanced in our literature and in rediscovering America it lent a human dimension to the grandiose nature of the continent. But this is a nature neither for the gods as in the texts of the Indians, nor a nature for heroes as in the writings of the romantics, but a nature for men and women in which the human problems will be addressed again with vigour and audacity.

As true Latin Americans the beauty of expression excites us and – for this reason – each one of our novels is a verbal feat. Alchemy is at work. We know it. It is no easy task to understand in the executed work all the effort and determination invested in the materials used – the words.

Yes, I say words – but by what laws and rules they have been transformed! They have been set as the pulse of worlds in formation. They ring like wood, like metals. This is onomatopoeia. In the adventure of our language the first aspect that demands attention is onomatopoeia. How many echoes – composed or disintegrated – of our landscape, our nature are to be found in our words, our sentences. The novelist embarks on a verbal adventure, an instinctive use of words. One is guided along by sounds. One listens, listens to the characters.

Our best novels do not seem to have been written but spoken. There is verbal dynamics in the poetry enclosed in the very word itself and that is revealed first as sound and afterwards as concept.

This is why the great Spanish American novels are vibrantly musical in the convulsion of the birth of all the things that are born with them.

The adventure continues in the confluence of the languages. Amongst the languages spoken by the people, in which the Indian languages are represented, there is an admixture of the European and Oriental languages brought by the immigrants to America.

Another language is going to rain its sparkle over sounds and words. The language of images. Our novels seem to be written not only with words but with images. Quite a few people when reading our novels see them cinematically. And this is not because they pursue a dramatic statement of independence but because our novelists are engaged in universalising the voice of their peoples with a language rich in sounds, rich in fable and rich in images.

This is not a language artificially created to provide scope for the play of the imagination or so-called poetic prose; it is a vivid language that preserves in its popular speech all the lyricism, the imagination, the grace, the high-spiritidness that characterise the language of the Latin American novel.

The poetic language which nourishes our novelistic literature is more or less its breath of life. Novels with lungs of poetry, lungs of foliage, lungs of rich vegetation. I believe that what most attracts non-American readers is what our novels have achieved by means of a colourful, brilliant language without falling into the merely picturesque, the spell of onomatopoeia cast by representing the music of the countryside and sometimes the sounds of the indigenous languages, the ancestral smack of those languages that flourish unconsciously in the prose that is used. There is also the importance of the word as absolute entity, as symbol. Our prose is distinguished from Castilian syntax because the word – in our novels – has a value of its own, just as it had in the indigenous languages. Word, concept, sound; a rich fascinating transposition. Nobody can understand our literature, our poetry if the power of enchantment is removed from the word.

Word and language enable the reader to participate in the life of our novelistic creations. Unsettling, disturbing, forcing the attention of the reader who – forgetting his daily life – will enter into the situations and personalities of a novel tradition that retains intact its humanistic values. Nothing is used to detract from mankind but rather to perfect it and this is perhaps what wins over and unsettles the reader, that which transforms our novel into a vehicle of ideas, an interpreter of peoples using as instrument a language with a literary dimension, with imponderable magical value and profound human projection.

Translated by The Swedish Trade Council Language Services.

Miguel Angel Asturias – Other resources

Links to other sites

On Miguel Angel Asturias from Pegasos Author’s Calendar

Miguel Angel Asturias – Nobel Lecture

Conferencia Nobel, el 12 de diciembre de 1967

La novela latinoamericana

Testimonio de una época

Hubiera querido que a este encuentro no se le llamara conferencia sino coloquio, diálogo de dudas y afirmaciones sobre el tema que nos ocupa. Empezaremos analizando los antecedentes de la literatura latinoamericana en general, deteniendo nuestra atención en aquellos que más atingencia tienen con la novela. Vamos a remontar las fuentes hasta los orígenes milenarios de la literatura indígena, en sus tres grandes momentos: Maya, Azteca e Incaica.

Surge como primera cuestión la siguiente pregunta: ¿Existió un género parecido a la novela entre los indígenas? Creo que sí. La historia en las culturas autóctonas tiene más de lo que nosotros occidentales llamamos novela, que de historia. Hay que pensar que estos libros de su historia, sus novelas, diríamos ahora, eran pintados entre los Aztecas y Mayas y guardados en formas figurativas aún no conocidas en el incanato. Presupone esto el uso de pinacogramas, de los que, la voz del lector, – los indígenas no distinguen entre leer y contar, para ellos es la misma cosa -, sacaba el texto que en forma de canto iba relatando a sus oyentes.

El lector, contador de cuentos cantados, o “gran lengua”, único conocedor de lo que los pinacogramas decían, realizaba una interpretación de los mismos recreándolos, para regalo de los que le escuchaban. Más tarde, estas historias pintadas se fijan en la memoria de los oyentes y pasan en forma oral, de generación en generación, hasta que el alfabeto traído por los españoles las fija en sus lenguas nativas con caracteres latinos o directamente en castellano. Es así como llegan a nuestro conocimiento textos indígenas poco expuestos a la contaminación occidental. La lectura de estos documentos es lo que nos ha permitido afirmar que entre los americanos la historia tenía más de novela que de historia. Son narraciones en las que la realidad queda abolida al tornarse fantasía, leyenda, revestimiento de belleza, y en las que la fantasía a fuerza de detallar todo lo real que hay en ella termina recreando una realidad que podríamos llamar surrealista. A esta característica de la anulación de la realidad por la fantasía y de la recreación de una superrealidad, se agrega una constante anulación del tiempo y el espacio, y algo más importante y característico: el uso y abuso de la palabra en estilo paralelístico, o sea el empleo paralelo de diferentes vocablos para señalar el mismo objeto, dar la misma idea, expresar los mismos sentimientos. Insisto en esto, el paralelismo en los textos indígenas es un juego de matices que para nosotros occidentales no tiene valor, pero que indudablemente permitían una gradación poética imponderable, destinada a provocar ciertos estados de conciencia que se tomaban por magia.

Volviendo al tema del origen de un género literario similar a la novela, entre los primitivos pueblos de América, cabría emparentar el nacimiento de la forma novelesca con la epopeya. La leyenda heroica, superando las posibilidades de la historia ficción, va en labios de los rapsodas, grandes lenguas de las tribus o “cuicanimes” que recorrían las ciudades recitando los textos, para que circulara entre los pueblos la belleza de sus cantos, como la sangre dorada de sus dioses.

Estos cantos épicos, tan abundantes en la literatura americana indígena, y tan poco conocidos, poseen eso que nosotros llamamos “intriga novelesca”, y que los frailes y doctrineros españoles designaban con el nombre de “embustes”.

Estos relatos novelados que en sus orígenes eran testimonio de su antigüedad, memoria y fama de las cosas grandes que en oyéndolas otros querían hacer, esta literatura de realidad y fantasía-realidad, se quiebra en el instante de avasallamiento, y queda corno una de las tantas vasijas rotas de aquellas grandes civilizaciones. Va a seguir, sin embargo, en esta misma forma documental no ya el testimonio de la grandeza, sino de la miseria, no ya el testimonio de la libertad, sino el de la esclavitud, no ya el testimonio de los señores, sino el de los vasallos, y una nueva literatura americana, naciente, intentará llenar los vacíos silencios de una época. Pero los géneros literarios que florecían en la península Ibérica no arraigan eri América, tal el caso de la novela realista y el teatro. Por el contrario es el borbotón indígena, savia y sangre, río, mar y miraje, lo que incide sobre la mentalidad del primer español que va a escribir la primera gran novela americana, “novela” como debe llamarse a la “Verdadera Historia de los Sucesos de la Conquista de Nueva España” por Bernal Díaz del Castillo. ¿Será atrevimiento llamar “novela” a lo que el soldado aquél llamó no historia sino “verdadera historia”? ¡Cuántas veces las novelas son la verdadera historia! Pero pregunto: ¿Será atrevimiento dar el nombre de novela a la obra del insigne cronista? Al que esto crea, a quien me llame atrevido, lo invitaría a internarse en la prosa trotona y anhelante de este hombre de infantería y de todas armas y advertirá que insensiblemente al entrar en ella, irá olvidando que lo que le sucedió era realidad y más le parecerá obra de pura fantasía. ¡Si hasta el mismo Bernal lo dice, próximo a los muros cíe Tenochtitlán: “que parecía las cosas de encantamiento que cuentan en el Libro de Amadís”! Pero este libro es español, se nos dirá, aunque de español sólo tiene el haber sido escrito por un peninsular avecindado en Santiago de los Caballeros de Guatemala, donde conservamos el glorioso manuscrito, y el haber sido trazado en la vieja lengua de Castilla, aunque más participa de ese disfracismo propio de la literatura indígena. Al mismo Don Marcelino Menéndez y Pelayo, versadísimo en letras clásicas hispánicas, le parece raro el sabor de esa prosa y le sorprende que haya sido escrita por un soldado. No para mientes el gran polígrafo en que Bernal a sus ochenta años no sólo había oído muchos textos de la literatura indígena, influenciándose con ella, sirio que por ósmosis se había absorbido América y ya era americano.

Pero hay otro parentesco más impresionante. Los indígenas, en sus últimos dolorosos cantos, ya avasallados, demandan justicia, y Bernal Díaz del Castillo se abre el pecho para dar salida a un cronicón que es un rugido de protesta, por el olvido en que se le dejó después “del batallar y el conquistar”.

A partir de este momento toda la literatura latinoamericana, el cantar y el novelar, va a tornarse no sólo en testimonio de cada época, sino como dice el escritor venezolano Arturo Uslar Pietri, en “Un Instrumento de Lucha”. Toda la gran literatura es de testimonio y reivindicación, pero lejos de ser un documento frío, son páginas apasionantes del que sabe que tiene en las manos un instrumento para deleitar y convencer.

¿El sur nos va a dar un mestizo? El mestizo por excelencia pues para que nada le faltara fue el primer desterrado que tuvo América: el Inca Garcilaso. Este desterrado criollo sigue las voces indígenas ya extinguidas, en su denuncia contra los opresores del Perú. El Inca nos ofrece en su prosa magnífica, ya no sólo lo americano, ni sólo lo español, sino la mezcla, en la fusión de las sangres y en la misma demanda de vida y de justicia.

De momento nadie advierte en la prosa del Inca el “mensaje” como se dice ahora. Esto quedará esclarecido durante la lucha de la independencia. El Inca aparecerá entonces con la prestancia del indio que supo burlarse del imperio “de los dos cuchillos” o sea la censura civil y eclesiástica. Tarde se dan cuenta las autoridades españolas del recado que encierra tanta donosura, imaginación y melancolía, y ordenan recoger sagazmente la historia del Inca Garcilaso, donde han aprendido esos naturales “muchas cosas perjudiciales”.

Y no sólo la poesía y obras de ficción dan testimonio. Los autores más insospechados, como los: Francisco Javier Clavijero, Francisco Javier Alegre, Andrés Calvo, Manuel Fabri, Andrés de Guevara, dieron nacimiento a una literatura de desterrados que es y seguirá siendo testimonio de su época.

Hasta el mismo poeta guatemalteco Rafael Landívar tiene su forma de rebelarse. Su protesta es silencio, a los españoles los llama “hispani” sin otro adjetivo. Y nos referimos a Landívar porque a pesar de ser el menos conocido debe considerársele como el abanderado de la literatura americana, cuando es auténtica expresión de nuestras tierras, hombres y paisaje. Landívar, dice Pedro Henriquez-Ureña, “es entre los poetas de las colonias españolas el primer maestro del paisaje, el primero que rompe decididamente con las convenciones del Renacimiento y descubre los rasgos característicos de la naturaleza en el Nuevo Mundo, su flora y su fauna, sus campos y montañas, sus lagos y cascadas. En sus descripciones de costumbres, de industrias y juegos hay una graciosa vivacidad y a lo largo cíe todo el poema, honda simpatía y comprensión por la supervivencia de las culturas indígenas.”

En Módena, Italia, aparece en 1781 con el título de “Rusticatio Mexicana” una obra poética de 3425 exámetros latinos, distribuida en 10 cantos, original de Rafael Landívar. Un año después en Bolonia aparece la segunda edición. Ante los europeos, el poeta llamado por Menéndez Pelayo “el Virgilio de la modernidad”, pregona en su obra las excelencias de la tierra, de la vida y del hombre americano. Ansiaba que los habitantes del viejo mundo supieran que al Vesubio y al Etna se les podía enfrentar el Jorullo, volcán mexicano, a las famosas fuentes de Castalia y Aretusa, las cascadas y grutas de San Pedro Mártir en Guatemala, y, al hablar del cenzontle, el pájaro de las 400 voces en la garganta, lo hacía volar más alto en el reino de la fama que el ruiseñor.

Canta los tesoros de la campiña, el oro y la plata que estaban llenando el orbe de valiosas monedas y los pilones de azúcar ofrecidos a las mesas de los reyes.

No faltan en el poema las estadísticas de la riqueza americana encaminada a deslumhrar al europeo. Cita las manadas de ganados caballares y vacunos, los rebaños de ovejas, los ganados caprino y porcino, las fuentes medicinales, los juegos populares, algunos desconocidos en Europa, como el palo volador, y no calla la gloria del cacao y del chocolate de Guatemala. Pero hay algo que debemos señalar en el canto landivariano: su amor al nativo. Canta en el indio a la raza que en todo sale airosa, pinta la maravilla de los huertos flotantes creados por los indios, los tiene como ejemplo de gracia y maestría pero no olvida sus inmensos sufrimientos. Así va dejando substancia poética, poesía naturalista ajena a lo simbólico, de un hecho que siempre ha querido negarse: la superioridad del indio americano como campesino, artífice y obrero.

A la pintura del indio malo, haragán y vicioso, tan propalada en Europa y tan creída en América por los americanos que lo explotan, Landívar opone la estampa del indio sobre cuyos hombros ha pesado y sigue pesando el trabajo en América.

Y no lo hace simplemente enunciándolo, caso en el que podía creérsele o no creérsele, sino que en su poema vemos al indio a bordo de la piragua placentera, transportando sus mercancías o viajando y lo admiramos extrayendo la púrpura y la grana, extendiendo los nivosos gusanos que producen la seda, agarrándose con tesón a las peñas para arrancarles el marisco precioso que da el color de las púnicas rosas, arando paciente y testarudo, cultivando el añil, extrayendo de la mina la nativa plata, agotando las venas de oro … El Rusticado de Landívar confirma lo que hemos dicho de la gran literatura americana, que no podrá conformarse con un papel pasivo, mientras en nuestros suelos, pueblos famélicos, vivan sobre estas tierras opulentas, y es por su contenido una forma de novelar en verso. Andrés Bello iba a renovar 50 años después la aventura americana en su famosa “Silva”, obra inmortal y perfecta en la que vuelve a aparecer la naturaleza del Nuevo Mundo con el maíz a la cabeza, como “jefe altanero de la espigada tribu”, el cacao en “urnas de coral”, los cafetales, el banano, el trópico en toda su potencia vegetal y animal, y contrastando con esta visión grandiosa “del rico suelo”, el habitante empobrecido.

Bello nos recuerda al Inca Garcilaso, por desterrado; es de la estirpe americana de Landívar; ambos inician, sin balbuceos, la gran jornada americana en la literatura universal.

A partir de este momento la imagen de la naturaleza del Nuevo Mundo, despertará en Europa un interés muy particular pero nunca llegará con la fidelidad candente que mantiene en Landívar y en Bello. Su visión deformada hacia lo maravilloso, idílico, paradisíaco, nos la ofrece Chateaubriand en “Átala” y “Los Nátchez”.

En los europeos la naturaleza es un telón de fondo sin la gravitación que alcanzará en el marco del romanticismo criollo. Los románticos dan a la naturaleza lugar permanente en las creaciones de poetas y novelistas de la época. Así José María de Heredia cantando a las Cataratas del Niágara, así Esteban Echeverría en las descripciones del desierto de “La Cautiva” para no citar a otros.

El romanticismo en América no fue solamente una escuela literaria sino una bandera de patriotismo. Poetas, historiadores, novelistas, reparten sus días y sus noches entre las actividades políticas y el sueño de sus creaciones. ¡Jamás ha sido más hermoso ser poeta en América! Entre los poetas influidos por la Patria convertida en musa, vemos aparecer a José Mármol, autor de una de las novelas más leídas en América, “Amalia”. Las páginas de este libro han pasado por nuestros dedos febriles y sudorosos, cuando sufríamos en carne propia las dictaduras que han asolado a Centro América. Los críticos al referirse – a la novela de Mármol señalan desigualdades, desaliños, sin darse cuenta que una obra de esa índole, se escribe con el corazón saltando en el pecho, pulsaciones que van a dejar en la frase, en el párrafo, en la página, esa taquicardia de la incorrección vital que aquejaba a la Patria entera.

Estamos en presencia de uno de los testimonios más ardientes de la novela americana. A través del tiempo “Amalia” como las imprecaciones de José Mármol, sigue sacudiendo a los lectores hasta constituir por ello, para muchos un acto de fe.

Y es en ese instante cuando va a sonar la voz de Sarmiento, plantando en la puerta de los siglos su famoso dilema: “Civilización o Barbarie”. Y el mismo Sarmiento se sobrecogerá cuando se dé cuenta que “Facundo” vuelve armas contra él y contra todos declarándose auténtico representante de la América criolla, de la América que se niega a morir y que busca hendir con el pecho que ya se le ha hecho duro, el esquema antitético de civilización o barbarie para encontrar entre estos extremos el punto en que sus pueblos integren con valores esenciales propios, su auténtica personalidad.

A mediados del siglo pasado otro romántico no menos apasionado aparece en Guatemala: José Batres Montúfar. En medio de las narraciones de carácter festivo el lector siente que debe olvidar la fiesta para escuchar al poeta. Con cuánta gracia cargada de amargura el inmortal José Batres Montúfar caló hondo en problemas que ya entonces, a mediados del siglo pasado, eran candentes.

Otra voz iba a llegar de norte a sur, le de José Martí. El estará presente, desterrado o en su patria, con su verbo encendido de poeta o de periodista, presente también con su ejemplo hasta su sacrificio.

El siglo XX se nos llena de poetas, de poetas que ya no dicen nada, salvo muy contados nombres, entre los que sobresalen el del inmortal Rubén Darío y Juan Ramón Molina, el hondureno. Los podas se evaden de la realidad, tal vez por ser esa una de las formas de ser poeta. Pero en muchos de ellos nada hay vivo en su obra que se va tornando habladuría. Ignoran la clara lección de los rapsodas indígenas, olvidan a los forjadores coloniales de nuestra, gran literatura, satisfechos en la imitación sin sangre de la poesía de otras latitudes, y ridiculizan a los que cantaron nuestra gesta libertadora, considerándolos encandilados por un patriotismo local.

Y no es sino pasada la primera guerra, que un puñado de hombres, hombres y artistas, salen a la reconquista de lo propio, van al encuentro de lo indígena, recalan junto a lo español materno y vuelven con el mensaje que tienen que entregar al futuro.

La literatura americana va a renacer bajo otros signos no ya el del verso. Ahora es una prosa táctil, plural e irreverente con las formas, herida por caminos de misterio, la que servirá a los designios de esta nueva cruzada cuyo primer paso fue hundirse, así, hundirse en la realidad, no para objetivar, forma de estar y no estar en ella, sino penetrando en los hechos para solidarizarse con los problemas humanos. Nada de lo que es humano, nada de lo que es real le será ajeno a esta literatura urgida por el contacto con América. Y este es el caso de la novela latinoamericana. Nadie pone en duda que esta novela va colocándose a la cabeza del género en el mundo entero. Se cultiva en todos nuestros países, por autores de diversas tendencias, lo que hace que también en la novela todo sea material americano, testimonio humano de nuestro momento histórico.

Y es que nosotros, novelistas del hoy americano, dentro de la tradición constante de compromiso con nuestros pueblos, en que se ha desarrollado nuestra gran, literatura, nuestra sustentadora poesía, también tenemos tierras que reclamar para nuestros desposeídos, minas que exigir para nuestros explotados y reivindicaciones que hacer en favor de las masas humanas que perecen en los yerbatales, que se queman en las plantaciones de banano, que se tornan bagazo humano en los ingenios azucareros, y por eso que para mí, la auténtica novela americana es el reclamo de todas estas cosas, es el grito que viene del fondo de los siglos y que se reparte en miles de páginas. Novela auténticamente nuestra que está de pie en sus páginas leales al espíritu, a los puños de nuestros obreros, al sudor de nuestros campesinos, al dolor por nuestros niños mal nutridos reclamando por que la sangre y la savia de nuestras vastas tierras corran otra vez hacia los mares para enriquecer nuevas metrópolis.

Esta novela participa, consciente o inconscientemente, de las características de los textos indígenas, frescos, lacerados y pujantes; de la angustia numísmata de los ojos de los criollos que asomaban a esperar el alba en la media noche colonial, más clara, sin embargo, que esta media noche que nos está amenazando ahora, y sobre todo de la afirmación, del optimismo lustral de aquellos hombres de pluma que desafiando a la inquisición abrieron en las conciencias brecha, para el paso de los libertadores.

La novela latinoamericana, nuestra novela, para ser tal, no puede traicionar el gran espíritu que ha informado, e informa, toda nuestra gran literatura. Si escribes novela sólo para distraer, ¡quémala! cabría decir evangélicamente, pues si no la quemas tú, se borrará contigo en el correr del tiempo, se borrará de la memoria del pueblo que es donde un poeta o novelista debe aspirar a quedar. ¡Cuántos hubo que en el pasado escribieron novelas para divertir! En todas las épocas. ¿Y quién los recuerda? En cambio qué fácil es repetir los nombres de los que entre nosotros escribieron para dar testimonio. Dar testimonio. El novelista da testimonio, como el Apóstol de los Gentiles. Es el Pablo que cuando intenta escapar se encuentra con la realidad rugiente del mundo que le rodea, esta realidad de nuestros países que nos ahoga y nos deslumbra, y al hacernos rodar por tierra nos obliga a gritar: ¿PARA QUÉ ME PERSIGUES? Sí, somos unos perseguidos de esta realidad que no podemos negar, que es carne de gente de la revolución mexicana, en los personajes cíe Mariano Azuela, de Agustín Yáñez y de Juan Rulfo, tan afilados de conceptos como sus cuchillos; que con Jorge Icaza, Ciro Alegría, Jesús Lara, es grito de protesta contra la explotación y el abandono del indio; que con Rómulo Gallegos en “Doña Bábara” nos crea a nuestra Prometea. Que con Horacio Quiroga nos devuelve a la pesadilla del trópico, pesadilla tan suya como americana que parece ser su estilo; que con “Los ríos profundos” de José María Arguedas, el “Río oscuro” del argentino Alfredo Várela, “Hijo de hombre” del paraguayo Roa Bastos, y “La ciudad y los perros” del peruano Vargas Llosa, nos hace ver cómo se desangra el trabajador en nuestras tierras. Con Mancisidor nos lleva a los campos petrolíferos, hacia donde van, abandonando sus casas, los habitantes de “Casas muertas” de Miguel Otero Silva … Con David Viñas nos enfrenta a la Patagonia trágica, con Enrique Wernicke nos arrastra con las aguas que sumergen pueblos y con Verbitsky y María de Jesús nos lleva a las villas miserias, los barrios dantescos e infrahumanos de nuestras grandes ciudades … El hijo del salitre de Teitelboim nos cuenta del duro trabajo en los campos salitreros, como Nicomedes Guzmán nos hace palpar la vida de los niños en los barrios obreros chilenos, y el campo salvadoreño en “Jaragua” de Napoleón Rodríguez Ruiz y nuestros pequeños pueblos en “Cenizas del Izalco” de Flakol y Clarivel Alegría. No podemos pensar en la pampa sin hablar de “Don Segundo Sombra” de Güiraldes, ni hablar de la selva sin “La vorágine” de Eustasio Rivera, ni de los negros sin Jorge Amado, ni de los llanos del Brasil sin el “Gran Sertao” de Guimaraes Rosa, ni de los llanos de Venezuela sin Ramón Díaz Sánchez.

Nuestros libros no llevan un fin de sensacionalismo o truculencia para hacernos un lugar en la república de las letras. Somos seres humanos emparentados por la sangre, la geografía, la vida, a esos cientos, miles, millones de americanos que padecen miseria en nuestra opulenta y rica América. Nuestras novelas buscan movilizar en el mundo las fuerzas morales que han de servirnos para defender a esos hombres. Está ya avanzado el proceso de mestizaje de nuestras letras al que correspondía en el reencuentro americano dar a su grandiosa naturaleza una dimensión humana. Pero ni naturaleza para dioses como en los textos de los indios, ni naturaleza para héroes como en los escritos de los románticos, naturaleza para hombres, en la que serán replanteados con vigor y audacia los problemas humanos. Aunque como buenos americanos nos apasiona la bella forma de decir las cosas, cada una de nuestras novelas es por eso una hazaña verbal. Hay una alquimia. Lo sabemos. No es fácil darse cuenta en la obra realizada del esfuerzo y empeño por lograr los materiales empleados, palabras. Sí, esto es, palabras, pero usadas con qué leyes. Con qué reglas. Han sido puestas como la pulsación de mundos que se están formando. Suenan como maderas. Gomo metales. Es la onomatopeya. En la aventura de nuestro lenguaje lo primero que debe plantearse es la onomatopeya. Cuántos ecos compuestos o descompuestos de nuestro paisaje, de nuestra naturaleza, hay en nuestros vocablos, en nuestras frases. Hay una aventura verbal del novelista, un instintivo uso de palabras. Se guía por sonidos. Se oye. Oye a sus personajes. Las mejores novelas nuestras no parecen haber sido escritas sino habladas. Hay una dinámica verbal de la poesía que la misma palabra encierra, y que se revela primero como sonido, después como concepto.

Por eso las grandes novelas hispanoamericanas son masas musicales vibrantes, tomadas así, en la convulsión del nacimiento de todas las cosas que con ellas nacen.

La aventura sigue en la confluencia de los idiomas. De todos los idiomas hablados por los hombres, además de las lenguas indígenas americanas que entran en su composición, hay mezcla de las lenguas europeas y orientales que las masas de inmigrantes llevaron a América.

Otro idioma va a regar sus destellos sobre sonidos y palabras. El idioma de las imágenes. Nuestras novelas parecen escritas no sólo con palabras sino con imágenes. No son pocos los que leyendo nuestras novelas las ven cinematográficamente. Y no porque se persiga una dramática afirmación de independencia, sino porque nuestros novelistas están empeñados en universalizar la voz de sus pueblos, con un idioma rico en sonidos, rico en fabulaciones y rico en imágenes. No es un lenguaje artificialmente creado para dar cabida a esa fabulación, o la llamada prosa poética, es un lenguaje vivo que conserva en su habla popular todo el lirismo, la fantasía, la gracia, la picardía que caracteriza el lenguaje de la novela latinoamericana. La poesía-lenguaje que sustenta nuestra novelística es algo así como su respiración. Novelas con pulmones poéticos, con pulmones verdes, con pulmones vegetales. Pienso que lo que más atrae a los lectores no americanos, es lo que nuestra novela ha logrado por los caminos de un lenguaje colorido, sin caer en lo pintoresco, onomatopéyico por adherido a la música del paisaje y algunas veces a los sonidos de las lenguas indígenas, resabios ancestrales de esas lenguas que afloran inconscientemente en la prosa empleada en ella. Y también por la importancia de la palabra, entidad absoluta, símbolo. Nuestra prosa se aparta del ordenamiento de la sintaxis castellana, porque la palabra tiene en la nuestra un valor en sí, tal como lo tenía en las lenguas indígenas. Palabra, concepto, sonido, transposición fascinante y rica. Nadie entendería nuestra literatura, nuestra poesía, si quita a la palabra su poder de encantamiento.

Palabra y lenguaje harán participar al lector en la vida de nuestras creaciones. Inquietar, desasosegar, obtener la adhesión del lector, el cual olvidándose de su cotidiano vivir, entrará a compartir el juego cíe situaciones y personajes, en una novelística que mantiene intactos sus valores humanos. Nada se usa para desvirtuar al hombre, sino para completarlo y esto es tal vez lo que conquista y perturba en ella, lo que transforma nuestra novela en vehículo de ideas, en intérprete de pueblos usando como instrumento un lenguaje con dimensión literaria, con valor mágico imponderable y con profunda proyección humana.

Miguel Angel Asturias – Banquet speech

English

Spanish

Miguel Angel Asturias’ speech at the Nobel Banquet at the City Hall in Stockholm, December 10, 1967 (in Spanish)

Majestad, Altezas Reales, Señoras y Señores:

Mi voz en el umbral. Mi voz llegada de muy lejos, de mi Guatemala natal. Mi voz en el umbral de esta Academia. Es difícil entrar a formar parte de una familia. Y es fácil. Lo saben las estrellas. Las familias de antorchas luminosas. Entrar a formar parte de la familia Nobel. Ser heredero de Alfredo Nobel. A los lazos de sangre, al parentesco político, se agrega una consanguinidad, un parentesco más sutil, nacido del espíritu y la obra creadora. Y esa fue, quizás no confesada, la intención del fundador de esta gran familia de los Premios Nobel. Ampliar, a través del tiempo, de generación en generación, el mundo de los suyos. En mi caso entro a formar parte de la familia Nobel, como el menos llamado entre los muchos que pudieron ser escogidos.

Y entro por voluntad de esta Academia cuyas puertas se abren y se cierran una vez al año para consagrar a un escritor y por el uso que hice de la palabra en mis novelas y poemas, de la palabra más que bella, responsable, preocupación a la que no fue ajeno aquel soñador que andando el tiempo pasmaría al mundo con sus inventos, el hallazgo de explosivos hasta entonces los más destructores, para ayudar al hombre en su quehacer titánico en minas, perforación de túneles y construcción de caminos y canales.

No sé si es atrevido el parangón. Pero se impone. El uso de las fuerzas destructoras, secreto que Alfredo Nobel arrancó a la naturaleza, permitió en nuestra América, las empresas más colosales. El canal de Panamá, entre estas. Magia de la catástrofe que cabría parangonarla con el impulso de nuestras novelas, llamadas a derrumbar estructuras injustas para dar camino a la vida nueva.

Las secretas minas de lo popular sepultadas bajo toneladas de incomprensión, prejuicios, tabús, afloran en nuestra narrativa a golpes de protesta, testimonio y denuncia, entre fábulas y mitos, diques de letras que como arenas atajan la realidad para dejar correr el sueño, o por el contrario, atajan el sueño para que la realidad escape.

Cataclismos que engendraron una geografía de locura, traumas tan espantosos, como el de la Conquista, no son antecedentes para una literatura de componenda y por eso nuestras novelas aparecen a los ojos de los europeos como ilógicas o desorbitadas. No es el tremendismo por el tremendismo. Es que fue tremendo lo que nos pasó. Continentes hundidos en el mar, razas castradas al surgir a la vida independiente y la fragmentación del Nuevo Mundo. Como antecedentes de una literatura, ya son trágicos. Y es de allí que hemos tenido que sacar no al hombre derrotado, sino al hombre esperanzado, ese ser ciego que ambula por nuestros cantos. Somos gentes de mundos que nada tienen que ver con el ordenado desenvolverse de las contiendas europeas a dimensión humana, las nuestras fueron en los siglos pasados a dimensión de catástrofes.

Andamiajes. Escalas. Nuevos vocabularios. La primitiva recitación de los textos. Los rapsodas. Y luego, de nuevo, la trayectoria quebrada. La nueva lengua. Largas cadenas de palabras. El pensamiento encadenado. Hasta salir de nuevo, después de las batallas lexicales, más encarnizadas, a las expresiones propias. No hay reglas. Se inventan. Y tras mucho inventar, vienen los gramáticos con sus tijeras de podar idiomas. Muy bien el español americano, pero sin lo hirsuto. La gramática se hace obsesión. Correr el riesgo de la antigramática. Y en eso estamos ahora. La búsqueda de las palabras actuantes. Otra magia. El poeta y el escritor de verbo activo. La vida. Sus variaciones. Nada prefabricado. Todo en ebullición. No hacer literatura. No sustituir las cosas por palabras. Buscar las palabras-cosas, las palabras-seres. Y los problemas del hombre, por añadidura. La evasión es imposible. El hombre. Sus problemas. Un continente que habla. Y que fue escuchado en esta Academia. No nos pidáis genealogías, escuelas, tratados. Os traemos las probabilidades de un mundo. Verificadlas. Son singulares. Es singular su movimiento, el diálogo, la intriga novelesca. Y lo más singular, que a través de las edades no se ha interrumpido su creación constante.

Miguel Angel Asturias – Biographical

Miguel Angel Asturias (1899-1974) was born in Guatemala and spent his childhood and adolescence in his native country. He studied for his baccalaureate at the state high school and later took a law degree at the University of San Carlos. His thesis on “The Social Problem of the Indian” was published in 1923.

After he finished his law studies, he founded with fellow students the Popular University of Guatemala, whose aim was to offer courses to those who could not afford to attend the national university. In 1923 he left for Europe, intending to study political economy in England. He spent a few months in London and then went to Paris, where he was to stay for ten years. At the Sorbonne he attended the lectures on the religions of the Mayas by Professor Georges Raynaud, whose disciple he became. Also, as correspondent for several important Latin American newspapers, he travelled in all the Western European countries, in the Middle East, in Greece, and in Egypt.

In 1928 Asturias returned for a short time to Guatemala, where he lectured at the Popular University. These lecture were collected in a volume entitled La arquitectura de la vida nueva (Architecture of the New Life), 1928. He then went back to Paris, where he finished his Leyendas de Guatemala (Legends of Guatemala), 1930. Published in Madrid, the book was translated into French by Francis de Miomandre, who sent his translation to Paul Valéry. The French poet was greatly impressed, and his letter to Miomandre was used as the preface to the 1931 edition published in the Cahiers du Sud series. The same year, Leyendas de Guatemala received the Silla Monsegur Prize, a reward for the best Spanish-American book published in France.

During his stay in Paris from 1923 to 1933, Asturias wrote his novel El Señor Presidente (The President), which slashed at the social evil and malignant corruption to which an insensitive dictator dooms his people. Because of its political implications Asturias was unable to bring the book with him when, in 1933, he returned to Guatemala, which at the time was ruled by the dictator Jorge Ubico. The original version was to remain unpublished for thirteen years. The fall of Ubico’s regime in 1944 brought to the presidency Professor Juan José Arévalo, who immediately appointed Asturias cultural attaché to the Guatemalan Embassy in Mexico, where the first edition of El Señor Presidente appeared in 1946.

In late 1947, Asturias went to Argentina as cultural attaché to the Guatemalan Embassy and, two years later, obtained a ministerial post. While in Buenos Aires, he published Sien de alondra (Temple of the Lark), 1949, an anthology of his poems written between 1918 and 1948. In 1948 he returned to Guatemala for a few months, during which time he wrote his novel Viento fuerte (Strong Wind), 1950, an indictment of the effect of North American imperialism on the economic realities of his country. That same year, the second edition of El Señor Presidente was published in Buenos Aires.

When the government of President Jacobo Arbenz Guzman fell in 1954, Asturias went into exile in Argentina, his wife’s native country, where he remained until 1962. A year later, the Argentine publisher Losada brought out his novel Mulata de tal (Mulata). This story, a surrealistic blend of Indian legends, tells of a peasant whose greed and lust consign him to a dark belief in material power from which, Asturias warns us, there is only one hope for salvation: universal love.

In 1966 Asturias was awarded the Lenin Peace Prize. In the same year, he was appointed the Guatemalan ambassador to France by President Julio Mendez Montenegro.

This autobiography/biography was written at the time of the award and first published in the book series Les Prix Nobel. It was later edited and republished in Nobel Lectures. To cite this document, always state the source as shown above.

Miguel Asturias died on June 9, 1974.