Speed read: Passive aggressive treatment

The first Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine acknowledged both the development of a scientific concept that concerned the way in which the immune system can fight certain infectious agents, and its successful translation into a method of keeping the illnesses they cause at bay. At the forefront of these achievements was Emil von Behring. His discovery of molecular missiles in blood led to a completely new type of therapeutic strategy, one in which immunity created through artificial means could cure life-threatening diseases.

Von Behring’s pioneering experiments were carried out on the then recently discovered bacteria that cause diphtheria and tetanus, diseases that both result from toxic substances released by the microorganisms. Working with Shibasaburo Kitasato, von Behring discovered that when animals were injected with tiny doses of weakened forms of tetanus or diphtheria bacteria, their blood extracts contained chemicals released in response, which rendered the pathogens’ toxins harmless. Naming these chemical agents “antitoxins”, von Behring and Erich Wernicke showed that transferring antitoxin-containing blood serum into animals infected with the fully virulent versions of diphtheria bacteria cured the recipients of any symptoms, and prevented death. What was true for animals was found to be true for humans; transferring such immune serum into children treated their symptoms of diphtheria, and stopped them dying of the disease.

After techniques were developed that could produce high-quality levels of antitoxin-containing blood extracts on an industrial scale, von Behring’s method of treatment, passive serum therapy, became an essential remedy for diphtheria, saving many thousands of lives every year. Thanks to his discoveries, these antitoxins, later called antibodies, also sparked a new line of scientific enquiry. Researchers rushed to seek other circumstances under which neutralizing antibody molecules are created to allow a host to acquire immunity to pathogenic organisms.

This Speed read is an element of the multimedia production “Immune Responses”. “Immune Responses” is a part of the AstraZeneca Nobel Medicine Initiative.

![]()

Emil von Behring – Nominations

Award ceremony speech

Presentation Speech by Professor the Count K.A.H. Mörner, Rector of the Royal Caroline Institute, on December 10, 1901

Your Royal Highnesses, Ladies and Gentlemen.

The interest in medical science which was expressed in Alfred Nobel’s will must have sprung from two roots.

His heart was warmly inclined towards everything which could be of use and benefit to humanity; he gave plenty of evidence of this both in his lifetime and in the clauses of his will.

Closely connected with this, but also, one might almost say, as an independent feeling, was his love for scientific research. This interest he brought not only to those questions which belonged to his immediate sphere of activity. I know from experience that Dr. Nobel occupied himself with the solution of medical problems and that he spared neither trouble nor expense to obtain an explanation of the question raised. A long time ago his love of medical research was already expressed through a large donation which he made to the Caroline Institute.

But it is hardly surprising that medical research had a fascination for a man of Dr. Nobel’s nature and attitude to life. He rated the medical sciences highly and placed great hopes on their successful development.

In this he was justified.

During the last century, medical science has developed in a manner never before paralleled. Already in the first half of the century fresh ground was broken and the foundations for further development were laid. The second half of the century has been even richer in important work and brilliant achievements.

There is not room here to even hint at all of them. I will permit myself to mention bacteriology and to remind you of Pasteur, the founder of this magnificent system of Science, of Robert Koch who made such splendid additions to it, of Lister who directed the beneficial application of this new science towards surgery.

I particularly wanted to mention bacteriology, because this has had the most extensive and revolutionary influence on the different branches of medical science. It must be well-known what a powerful influence it has had on our concept of general hygiene and how it has left its mark on almost everything which is done in this connection. The splendid development of surgery and all sciences connected with it is largely thanks to bacteriology.

In the branches of pure medical science, too, bacteriology has already produced mature fruits of the highest value, while those still being developed are too numerous to be accounted.

Through the knowledge that bacteria engender disease and through our insight into their living conditions, the possibility of conquering the diseases is revealed, even in those cases where the bacteria have obtained a firm foothold and are developing in the organism. The most splendid proof so far of what can be done in this direction is offered in the case of diphtheria.

As far back in time as the knowledge of human illnesses extends, diphtheria and its modification croup have been a scourge of the human race. At times the incidence has, it is true, decreased, so that it apparently ceased to exist, but always, after some time, it has flared up again, causing devastating epidemics of greater or lesser extent. For many decades it has raged among the different nations of the civilized world.

I need not describe the terror which it caused and the despair left in its trail in families from which it tore one member after another. Now, conditions are greatly changed and the picture can be painted in very much lighter colours.

Of course diphtheria still presents a threat and will probably always do so. One can hardly hope ever to reach a stage where it will be completely stamped out, or that in each case there will be a happy ending. But the fight against it is no longer so unequal as it once was. It can be conducted with confidence and hope now that we have a weapon against it which, in thousands of cases, has proved extremely effective.

The year 1883 marks a turning-point in the history of diphtheria. It had been assumed earlier by one or two workers that diphtheria was a disease which was caused by bacteria, but on the other hand this was contested by prominent experts. Nothing positive was known and there had been no scientific argument on the subject. Still less could it be said that there was any certain knowledge of the kind of illness-producing parasite involved.

In the above-mentioned year Löffler completed his comprehensive and extremely significant investigation on the bacteriology of diphtheria. This investigation laid the foundations for the further development of the study of diphtheria treatment. Because of Löffler’s work, the foe was obliged to drop his mask and make known his battle tactics. Using his own weapons against him was to be reserved for later.

In general, the disease-causing bacteria produce poisons which in their turn give rise to a toxic condition in the individual in which they develop. And it is precisely because of these poisons that the bacteria are so dangerous. Nevertheless, it has been shown that the poisons, under certain conditions, will lead the organism to produce substances which render them harmless and which prevent the development of the bacteria. When such a condition of «immunity» has been built up, the individual can become insensitive to the baceria in question and resistant to the poisons.

These facts have in many respects proved to be of great practical importance and capable of immediate application.

But it was necessary, nevertheless, in order to achieve success in the battle against diphtheria, to carry research another step forward. Science has succeeded in doing this and results have been obtained which are of the greatest practical significance with regard to diphtheria and also other diseases.

Blood fluid – or blood serum – from an individual who has been immunized with poisons from a certain bacterium, can, namely, when introduced into the organs of another individual, confer resistance upon him against the bacterium in question. Upon this fact modern serum therapy is based.

Up until now, serum therapy has had particularly splendid triumphs in the case of diphtheria, but its significance is not limited to this disease but extends much further. The field which is opened up for research by the development of serum therapy has therefore – for the present – no discernible limits. Much ground has been gained already and we are justified in expecting a great deal of important progress.

The pioneer in this new area of medical research, Professor Emil von Behring, has been chosen by the Professorial Staff of the Caroline Institute as the recipient of this year’s Nobel Prize for Medicine.

Geheimrat Professor von Behring. In proclaiming that the Staff of Professors of the Royal Caroline Institute has decided to award you the Nobel Prize in the prize-section for Physiology or Medicine, I am announcing a name which is already renowned.

This beneficial and revolutionary work of yours is not only known and famous in this country but over the whole of the civilized world – and rightly so.

You have prepared the way for a huge and significant step forward in medical research; you have provided mankind with a reliable weapon against a devastating disease.

Emil von Behring – Nobel Lecture

Nobel Lecture, December 12, 1901

Serum Therapy in Therapeutics and Medical Science

Serum therapy in the form in which it finds application in the treatment of diphtheria patients is an antitoxic or detoxicating curative method. It is based on the view, held by Löffler in Germany and by Roux in France, that the parasites causing diphtheria, the Löffler diphtheria bacilli, do not themselves cause diphtheria, but that they produce poisons which cause the disease to develop. Without this preliminary work by Löffler and Roux there would be no serum treatment for diphtheria.

When the diphtheria poison is rendered harmless within the human organism, then the diphtheria bacilli behave like the innumerable micro-organisms which we absorb without suffering harm every day and like those micro-organisms which correspond morphologically with the diphtheria bacilli, but, from the outset, have no capacity to produce poisons (pseudo-diphtheria bacilli). The poison excreted by the bacilli is the diphtheria bacilli’s dangerous weapon against the human being, without which weapon they would be delivered over helplessly to the natural prophylactic power of the living human organism.

The way in which the diphtheria bacilli, after penetrating into the human body, release then poison and how this poison develops its destructive activity has been the subject of many interesting investigations, the result of which can be summed up briefly as follows: In a typical clinical picture of diphtheria in human beings, as summarized for the first time 80 years ago by the Frenchman Bretonneau, the diphtheria bacilli are first localized in the pharyngeal amygdala, which, in all probability, they reach principally via the breath, but also in substances which we take in by way of nourishment. In the niches and small cavities of the amygdala the diphtheria bacilli can multiply as though in an artificial incubator and excrete their poisons. In animals, the organ, called “amygdala” tonsils) on account of its shape (L. “amygdala” = almond), is missing and this is probably the reason why epidemics of diphtheria are the tragic privilege of human beings. The diphtheria poison gets into the blood stream by way of the lymphatic vessels and starts up inflammatory processes from there in the various organs. The inflammatory symptoms are outwardly visible chiefly in the proximity of the site of production, on the pharyngeal mucous membrane and in the larynx.

If we now introduce the diphtheria serum as an antitoxin into the blood by injecting it under the skin, this antitoxin will reach all parts of the body to which the blood has access. If the injection takes place at a time when the diphtheria bacilli have not yet begun their destructive activity, then the secondary inflammatory phenomena of diphtheria toxicity will not arise. We speak then of immunization or of preventative or prophylactic serum therapy. If, on the other hand, the toxic process has already begun, then the already existing inflammatory processes will follow their natural course, for the anti-toxin exerts no influence, either useful or harmful, on the substrata of the inflammation, on the cells and organs. In this case, all that can influence the already existing disease is firstly to render harmless the poison which has already reached the body fluids, and secondly to prevent the entry of fresh supplies of active poison into the blood stream. It is easily understandable that the diphtheria serum has an abortive action, but it is not the disease which is cut off but the creation of new disease-engendering substances.

It will be seen from this how important early use of diphtheria serum is. The longer one delays the injection after the start of the illness, the more existing focal points of inflammation and the more disturbances of vital functions will threaten health and life.

In addition, a certain time must elapse from the injection of the serum until its antitoxic and healing activity in the affected parts of the body can develop. Also, serum injected under the skin does not pass straight into the blood vessels but first into the lymphatic vessels. From here it takes several hours before passing gradually into the blood stream and further time still is needed before it is diffused, not only everywhere in the blood stream, but also into the extra-vascular poison-containing fluids. This interval between injection and detoxification can mean the difference between life and death for the threatened individual and I have asked myself whether, in the interest of the patient, this interval could not be shortened. It can indeed be done if the serum is injected directly into the blood stream instead of under the skin. According to experimental investigations carried out by my erstwhile collaborators, Dr. Knorr and Dr. Ransom, about 8 hours can be saved in this way. Furthermore, it is possible to have a local effect on the poison-producing localities by using dilute serum solution as a mouth wash to rinse the poisoned pharyngeal organs. So that we may recognize the position which serum therapeutics have gained in the treatment of diseases, as compared with other methods in medicine, I hope you will allow me to use one or two technical terms, not only because these have, during the course of time, come to embody a well-known and generally respected concept, but also because these technical expressions, taken from Latin and Greek, are more suited to international understanding than more modern expressions which we might use in their place.

Since earliest times, in that sphere of medicine which is responsible for the analysis of the symptoms of disease, their cause and natural or artificially induced conquest, namely pathology, humoral and solidistic pathologists have been in opposition to one another. In the last century the solidistic pathologists won the upper hand and the form which Virchow has given to the solidistic pathology by the foundation of cellular pathology is now so firmly established that the old humoral pathology can probably be regarded as having been finally laid to rest. With the victory of solidistic pathology, however, there has now arrived, pari passu, in the teaching hospitals a solidistic and cellular therapy of which one cannot speak so highly as in the case of the cellular pathology.

In the treatment of wounds, solidistic trend in therapy expressed itself more in salves, balsams, alteratives, which were supposed to influence the diseased body elements in ill-looking wounds to new and different activity. As you know, this aspect of solidistic therapy has vanished from medicine since Lister, with epoch-making success, laid down the principle, which he taught us to follow down to the smallest detail: “Keep fingers away from wounds, leave the cells as much as possible undisturbed, but take care that noxious agents from outside are kept away from wounds and cells”.

In internal medicine, however, solidistic therapy remained “faute de mieux”. New remedies were constantly coming on to the market and into use in practice which were supposed to curb, with anti-febrins, the vigorous activity of the cells aroused by fever, encourage the will to live and alter the misdirected cell activity. I do not need to quote instances when I maintain that we were all reared in the solidistic- and cellular-therapy dogma according to which the morbid manifestations of life are and must remain the subject of internal therapy. A glance at any Government-sanctioned Pharmacopoeia will show that even now medicaments are classified against a background of this viewpoint.

The detoxicating, or as it is also called, the antitoxic serum therapy, is, on the other hand, humoral therapy. Just as little as it has any direct influence on the diphtheria bacilli, is it able to have any direct action, whatever, on the living body elements of the patient who either has, or is threatened with, diphtheria. The detoxicating process acts exclusively in the body fluids, in the blood, in the lymphs and in the pericellular lymphatic areas. I must emphasize this especially, because many authors take the view that the diphtheria anti-toxin can also neutralize the poison which has penetrated into the body cells and become established there. My own experience runs entirely contrary to such a view.

Serum therapy in the treatment of diphtheria is, therefore, humoral therapy in the strictest sense of the word. It leads us back to the supposedly long-abandoned crasis theory which attributed an important role in the development and overcoming of disease to the peculiarities of the mixing of the substances solved in the body fluids. As long as there is active diphtheria poison in the body fluids, then a dyscrasia exists. After inactivation of the diphtheria poison, or in other words after the detoxication of the body fluids by the addition of diphtheria antitoxin, the dyscrasia is overcome; in its place appears, so to say, a eucrasia. I do not object if someone tells me that the process of disease does not consist in a faulty mixture of fluids, but in the abnormal functioning of living body elements, the solids of the whole organism. In this sense, there can, in fact, only be solidistic pathology or cellular pathology, and never humoral pathology since, indeed the lifeless, inert body fluids cannot be attacked by any ![]() or illness. In so far, however, as the diseased function of the living body elements is, in the main, conditioned by the incorrect mixture of body fluids, I find the linguistic inconsistency of the use of the word humoral pathology no worse than if one speaks of pathological anatomy, although the subject matter of this discipline concerns cadaver anatomy and

or illness. In so far, however, as the diseased function of the living body elements is, in the main, conditioned by the incorrect mixture of body fluids, I find the linguistic inconsistency of the use of the word humoral pathology no worse than if one speaks of pathological anatomy, although the subject matter of this discipline concerns cadaver anatomy and ![]() cannot really be attributed to cadavers. However this may be, no one doubts any more of the existence of a humoral therapy since antitoxic diphtheria therapy has found an assured place for itself in medicine.

cannot really be attributed to cadavers. However this may be, no one doubts any more of the existence of a humoral therapy since antitoxic diphtheria therapy has found an assured place for itself in medicine.

I must add another important epithet to the word serum therapy in order to characterize its position in medicine. It is aetiological therapy in contrast to the symptomatic therapy just described. As in the case of the Lister treatment of localized wound infections, serum therapy also, in the treatment of general infections, holds to the principle “leave the cells in peace and simply take care that noxious agents from outside are kept out, or, if they once get into the body, are removed”. The internal anti-infectious therapy would appear to have the more difficult task, and as long as it was thought that anti-infectious activity could only be carried out by killing the living disease germs, the pessimists appeared to be justified in making the discouraging statement that “internal disinfection would always remain impossible”. If now an internal disinfection has, nevertheless, been achieved, this is not thanks to speculation or change of doctrine, but thanks to the fact that Nature herself has been taken as a guide. I doubt whether it will ever be possible to establish artificially the antitoxic principle of serum therapy in diphtheria, without the aid of vital organization and secretion faculties. It is one of the most wonderful things imaginable to see how the supply of poison becomes the prerequisite for the appearance of the antidote in the poisoned living organism, how then the antidote in the blood reaches a state of almost unbelievable antitoxic energy through the systematic increase of the poison supply, how the bearers of this energy, the albumins and globulins of the blood, show no sign of any chemical change whatever, how the newly-won energy is so elective that we have no other means of proving its existence than solely by the diphtheria poison.

An attempt has been made to make a comparison between the method of action of the antitoxic serum albumin on the poison molecules with other compensating and inactivating processes. In my first work, I myself used the non-prejudicial expression “rendering the poison harmless”, replacing it later, following Ehrlich*, with the better sounding expression “poison destroying”. But I gave up this expression as well when I realized that I was being credited, on account of it, with the assumption that the poison molecule would be, to a certain extent, demolished and so become non-poisonous. I began then to speak of “neutralization”, but right from the start I secured myself against the opinion that the antitoxic and the toxic protein combine in a way which resembles the formation of salts from acid and alkali. Now I prefer to use the word “detoxication” which makes no reference to the method of action. But if I want to indicate roughly how I imagine this detoxicating process, then I speak of “inactivation”. I imagine, in fact, that, as regards chemical analysis, the antitoxic and the toxic protein stay exactly the same after detoxication as before; what changes is simply the activated condition; in the same way as the conductors of positive and negative electricity, before and after compensation of their active conditions, remain the same substances in terms of chemical analysis. Perhaps, at some later date, work in the physico-chemical border territory which you here see represented by such illustrious names as van’t Hoff and Arrhenius will bring us to the point where we can refer to active protein without the need of talking in parables!

With this example of antitoxic diphtheria therapy, I have attempted to enumerate for you the chief characteristics of serum therapy as a novum in therapeutics and as a progressive step in medicine.

It is a humoral therapy, because its activity develops only within the fluid and solved components of the individual who is ill or threatened with illness. It has an anti-infectious action brought about by internal disinfection, but is, in this respect, in contrast to the anti-bacterial disinfectant treatment methods which, for example, can be carried out in laboratory experiments with the aid of the R. Pfeiffer’s bacteriolysin; because its activity is only detoxication, we call it antitoxic. Because it does not influence the substrata of the diseased manifestations, the cells and organs, but only the cause of the disease, I call it aetiological therapy, which comes to approximately the same thing as the therapeutic endeavours which are referred to in other quarters as causal, radical, abortive, etc.

Now I must speak on a special subject in which serum therapy takes its place with those methods of combating infectious diseases such as Jenner’s smallpox vaccination, Pasteur’s anthrax prevention, Pasteur’s hydrophobia treatment, and Koch‘s tuberculin therapy.

These kinds of treatment can be indicated as isotherapeutic methods because they treat the infectious diseases with media which are of the same kind as the disease-causing, infective substances. Briefly expressed, serum therapy works through anti-bodies, iso-therapy through iso-bodies.

You know that by treating horses with an iso-body, the diphtheria poison, we obtain the curative anti-body. In explaining the nature of isotherapy, I would like, however, to start with an example where, for me, the isotherapy is not just a means to an end, but an end in itself. This is the case in the experiments which I have been carrying out for a number of years in Marburg with the purpose of combating tuberculosis in cattle.

As you know, tuberculosis in cattle is one of the most damaging infectious diseases to affect agriculture. It causes premature death in affected animals, damages nutrition and milk production and is the cause of inferior meat. Furthermore, it is feared as being a carrier of tuberculosis to humans, although admittedly R. Koch recently disputed this.

In different countries, or in different regions of the same country, the disease does not always strike with the same violence and frequency. Thanks to the support of Count Zedlitz, the Lord-Lieutenant of Hesse-Nassau, I have been in a position to ascertain some remarkable statistical facts in this connection. As a result of many thousands of tuberculin inoculations in two areas of the province of Hesse, I at first thought that the question of breed played an important part. It appeared, namely, that in the heavy, high milk-yielding strains (Dutch, Friesian and Swiss cattle) 30 to 40% showed a tuberculin reaction, whereas in an exceptionally pure breed of red cattle, raised in Hesse, the so-called Vogelsberger cattle, there was less than 1%. However, comparative infection experiments carried out ad hoc in Marburg showed no differences in susceptibility, and extensive research led finally to the explanation that the number of cattle reacting to tuberculin is, in the main, dependent upon whether any or few cattle are kept permanently in the same stalls. It appeared that, quite independent of hygienic feeding and living conditions, in almost every case the cow-houses with 20 and more cattle were heavily vitiated, whereas the small-man’s cows kept in small stables only very occasionally reacted to tuberculin. The large cow-houses were nearly all occupied by heavy, high milk-yielding strains and the small ones by red cattle. And when, in the neighbouring area of Giessen-Gutshofen, the Vogelsberger cattle, which were in large numbers kept together in one building, were submitted to tuberculin tests the proportion of animals which reacted was also very high.

When making these observations, attention was also paid to whether, in those areas which had been pointed out to us by the authorities as being suspected breeding grounds for human tuberculosis, an especially large number of cases of bovine tuberculosis was present. But such a coincidence was definitely not found to exist.

One could feel inclined to use this observation (which I passed on to the Lord-Lieutenant at the beginning of this year in an official report) as corroborative evidence for the view expressed by R. Koch that the tubercle bacilli are different in humans and in cattle. My own observations, however, point more to the view that spontaneously occurring cases of cattle tuberculosis are no more caused by passing contact than is the case with humans, but that rather cohabitation of long duration is required if infection leading to tuberculosis is to be passed from individual to individual.

In my experience cattle are on a relatively low susceptibility plane with regard to tuberculosis infection. In a series of cases, I introduced tuberculosis virus, from pearl nodules containing tubercle bacillus, under the skin direct from animal to animal, achieving in this way nothing more than a local tuberculosis with extensive proliferation of bacilli, which after existing for months completely disappeared. After intravenous injection of the emulsified pearl nodules I observed a general feverish condition lasting for weeks, but which also cleared up spontaneously. Many of these spontaneously cured cattle I later infected together with fresh control cattle in such a way that the latter died of acute miliary tuberculosis in 4-6 weeks, whereas those which had recovered earlier were quite healthy again after a short indisposition.

If there is to be any certainty of cattle dying after a single, arbitrary infection with tuberculosis virus, it is essential that consideration be given to the following main factors:

(1) origin and special composition of the virus;

(2) method of application;

(3) dosage.

I can confirm absolutely Koch’s statement that many tubercle-bacilli cultures of human origin are no more dangerous to cattle than Arloing’s homogeneous bacilli culture is to guinea-pigs.

In my own experiments with tubercle bacilli of human origin which were avirulent to cattle, cultures were always used which had been cultivated for years in the laboratory. If, however, I used human cultures for cattle infection which had only recently been cultivated from tubercular sputum, they proved by no means unharmful. In the same way, those human bacilli which had become avirulent to cattle through long-continued culture in the laboratory can act again with considerable virulence in cattle if they are first used to infect goats and then, after the death of the animals, are cultivated from the carcases. I have a strain of human-goat tubercle bacilli which, after culture, is probably the most virulent of all to cattle.

There is more probability that cattle-virulent cultures can be obtained without first being passed through goats if the culture stock is obtained from the body of the cattle. Even here, however, I have gained the impression that a long period of cultivation on artificial nutrient medium curtails the disease-causing activity in cattle.

It is very noteworthy here that one must certainly not conclude that the loss of disease-causing activity for cattle necessarily means a decrease in virulence for other animals. The Pasteur Anthrax studies establish, in fact, that there is a definite scale for the decline in virulence. A weakened anthrax strain no longer fatal to mice is not fatal to any other kind of animal either, and one which is virulent for rabbits proves always extra virulent for guinea-pigs and mice. It would be very surprising indeed and would strain credulity if anyone were to report an anthrax strain which is virulent for rabbits, but not for mice and guinea-pigs. There is a firm scale here in accordance with which all anthrax strains, wherever and however they may be obtained, act with greater disease-causing energy in mice than in guinea-pigs, and with greater energy in guinea-pigs than in rabbits.

In the case of tuberculosis things are different. I have studied with special care in this direction three tubercle bacilli modifications: tubercle bacilli from human beings (Tb-Hu), tubercle bacilli from cattle (Tb-Ca) and tubercle bacilli weakened according to Arloing (Tb-Arl). Tb-Hu and Tb-Ca remain, with great obstinacy, virulent to guinea-pigs and rabbits, but behave differently, in so far as Tb-Hu loses its Ca-virulence more quickly than Tb-Ca. Tb-Arl are harmless to human beings; in rabbits and horses, when injected intravenously, they cause severe illness which can quite soon end in death with symptoms of pneumonia.

For my tuberculosis strains, therefore, I have a quite different virulence scale, according to the kind of animal which is being taken as standard. The reaction of horses is quite exceptionally striking. In these animals the tubercle bacilli obtained from cattle show the lowest degree of virulence.

As regards my methods, I test the disease-causing energy in cattle in three ways: through infection from the subcutaneous tissue, through intravenous injection of the emulsified tuberculosis virus, and through intra-ocular infection. With my assistant, Dr. Römer, I have found that intra-ocular infection is the most effective. I was led to this method of infection by a study of the work of Professor Baumgarten of Tübingen and I now use the intra-ocular infection method to determine the degree of artificially achieved tuberculosis immunity in my cattle. Next I use intravenous infection and lastly subcutaneous infection.

Even when using the tubercle bacilli most virulent to cattle, the culture dose must not be too small in the case of intravenous infection if it is required to cause an illness severe enough to lead to the death of the animal. As an average dose for this purpose, I take 0.04 g from a culture not more than 6 weeks old. The quantity of bacilli contained in this dose corresponds approximately to 2 cm3 of tuberculosis bouillon culture. With intra-ocular infection, a much stronger action is achieved with a much smaller quantity of bacilli. Here the propagation rate in the eye itself is very considerable.

After observing several cases of spontaneous recovery in tuberculosis-infected cattle, the thought occurred to me that the tubercle-bacilli modifications which were only slightly active in the case of cattle behaved in the same way as the vaccines to the destructive virus. I then undertook an experiment aimed at systematically rendering young cattle immune to tuberculosis with living tubercle bacilli. An exact description of these immunization experiments, with detailed records and temperature curves, will most probably follow in March of next year in my “Beitrage zur experimentellen Therapie”. At this point, I should like to emphasize the following results: in the case of cattle, I forego the subcutaneous preliminary treatment and use instead exclusively the intravenous injection. As immunization vaccine I use a little Ca-virulent Tb-Hu (3267), then go over to Tb-Ca (Nocard) and, finally, I use nothing stronger in the way of tuberculosis virus than a goat-passage culture.

I have also made experiments using an originally strong tuberculosis virus which has then been dried under vacuum conditions at room temperature and left standing for a long time, whereby its disease-causing potential is greatly reduced. Where pure cultures on artificial nutrient media were concerned, I was not very satisfied with the results; the experiments with dried pearl nodules and tubercular organs from cattle turned out better.

If, on account of the preliminary treatment, a cow became immune to Ca-virulent Tb-(cultures), then there was also an immunity against Ca-virulent Tb-Hu (goat-passage) and vice versa. This does not appear to confirm that Tb-Hu and Tb-Ca are different in kind.

After my Marburg experiments showed the possibility of tuberculosis immunization for cattle, we were now faced with the task of finding out, by research through special experiments, in how short a time and with what minimum of detriment to the animal to be immunized and financial sacrifice, tuberculosis protection for cattle could be achieved in practice. In order to carry out these investigations, I procured for myself living space and grazing ground for a large number of cattle and I am hoping to use the large money award which has come to me through the Nobel Foundation to show the possibility and practicability of fighting tuberculosis in cattle along the lines of Pasteur’s protective inoculation to a larger extent than up to now. It would give me much honour and pleasure if any among you would care to inspect my Marburg work and installations on the spot and see, at the same time, how I am using my best endeavours, in accordance with the intention of the noble founder himself, Alfred Nobel, to promote the common good.

I need hardly add that the fight against cattle tuberculosis only marks a stage on the road which leads finally to the effective protection of human beings against the disease. Here, however, it has been my intention to report on facts, not hopes. And it is as a fact that I think I am able to report the immunization of cattle against tuberculosis to you.

*As far as I can ascertain, the expression “poison destruction” appears for the first time in the Abrin study by Ehrlich in the year 1891 (Deut. Med. Wochschr. 1891).

The Nobel Foundation's copyright has expired.Emil von Behring – Photo gallery

Emil von Behring

Source: Philipps-Universität Marburg. Photographer unknown. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Emil von Behring (back row, fourth from left) with international tuberculosis researchers in front of his Schlossberg laboratory in Marburg on 28 October 1902

Photo: Wilhelm Risse, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Emil von Behring. Lithograph.

Courtesy: Jacob van 't Hoff Collection, Ms. 74, Special Collections, The Sheridan Libraries, The Johns Hopkins University

Emil von Behring – Banquet speech

Emil von Behring’s speech at the Nobel Banquet in Stockholm, December 10, 1901 (in German)

Trotz seiner verhältnismässig geringen Einwohneranzahl hat Schweden auffallend wirksam in den Gang der Menschengeschichte und immer in solcher Weise eingegriffen, dass man den Eindruck des Gewaltigen davon tragen muss.

Ich erinnere hier an die vorgeschichtlichen mythischen Gestalten, die in unseren gemeinschaftlichen germanischen Sagen die nordischen Naturmächte verkörpern; weiter auch an die kühnen Seefahrer, die Wikinger, und ihre grossen Taten, später an die kriegerischen und freundschaftlichen Beziehungen zum Deutschtum, bis in Gustav Adolf ein Held entstand, der wie kaum ein einheimischer in unserer Geschichte fortlebt.

Die grossen Dichter des Nordens bringen mich auf die Gegenwart und auf Alfred Nobel, der gleichfalls in seiner ohne gleichen dastehenden Stiftung die Grenzen seiner Heimat überschreitet und den grossen Wesenszug erkennen lässt, den man an den bedeutenden Männern Ihres Landes zu bewundern gewohnt ist.

Ich schliesse mit dem Wunsche, dass es Ihnen auch in der Zukunft niemals fehlen möge an Landessöhnen mit diesem Zug ins Grosse und Gewaltige – sowie auch mit dem Versprechen, dass ich den mir zuteil gewordenen Geldpreis verwenden will zur Fortsetzung meiner Tuberkulosebekämpfungsarbeiten mit aller mir zu Gebote stehenden Energie. Ich erlaube mir hiermit, schwedische Forscher nach Marburg einzuladen, um dort zu sehen, in welchem Sinne ich mein Versprechen einzuhalten mich bestreben werde.

Prior to the speech, Professor the Count K.A.H. Mörner, Rector of the Royal Caroline Institute, addressed the laureate (in German):

“Herr Geheimrat Professor von Behring!

Es ist für alle Mediziner erquickend, zu einer Zeit zu leben, in welcher die medizinischen Wissenschaften eine so grossartige Entwickelung erhalten haben, wie es jetzt der Fall ist. Wir freuen uns darüber.

Einen noch näher liegenden Grund, uns zu freuen, haben wir heute, wo wir in unserem Kreise einen Mann begrüssen, der so gewaltig zu dieser Entwickelung beigetragen hat, wie Sie, herr Professor, es gethan haben.

Die Bakterien, welche früher als zügellose Horden umherschweiften, werden jetzt immer mehr gebändigt und in disziplinierte Scharen geordnet, welche den Geboten der Wissenschaft gehorchen müssen. So ziemlich nach Belieben kann man sie fern halten, wo man dies wünscht, und andererseits können die Bakterien Dienste zu leisten genötigt werden.

Auf dem Grund und Boden, welchen der grosse Altmeister Pasteur und der geniale Robert Koch bebaut haben, sind mehrere neue Sprosse der medizinischen Wissenschaften entwickelt worden. Ich lasse bei Seite die moderne Chirurgie, die allgemeine Gesundheitspflege und mehrere andere Gebiete, wo die Bakteriologie für die menschliche Haushaltung bedeutungsvoll gewesen ist.

Ich will nur den Bereich erwähnen, wo Sie als Bahnbrecher gewirkt haben und immer noch der Voranschreitende sind, – ich meine die Lehre von der Serumtherapie und besonders die Erfindung des Diphterie-heilserums.

Mit scharfsehendem Auge haben Sie einen Weg gefunden, um die Ergebnisse der Immunitätslehre für therapeutische Zwecke zu verwerten. Mit genialem Geschick und beharrlicher Ausdauer haben Sie diese Lehre entwickelt und die Hindernisse siegreich überwunden.

Sie haben dadurch den Kaum der medizinischen Wissenschaften um einen Zweig bereichert, welcher schon jetzt von der allergrössten Bedeutung ist und es in noch höherem Grade werden wird, wenn alle Knospen erblüht und alle Früchte gereift sind.

Wir huldigen also in Ihnen den genialen Forscher, aus dessen geistigen Schaffen die Entdeckung der Serumtherapie entsprungen ist.

Die schwedischen Ärzte, und die Ärzte aller Länder verdanken Ihnen eine siegreiche Waffe gegen Krankheit und Tod, welche dieselben aus Ihren Händen erhalten haben. Wenn sie alle auf einmal sprechen könnten, würden sie auch einstimmig die tiefempfundene Dankbarkeit von tausend und aber tausend Menschen bezeugen, welche ihre Angehörigen aus lebenbedrohender Gefahr durch Ihre Arbeit gerettet gesehen haben.

Herr professor von Behring, wir bringen Ihnen unsere Glückwünsche und unsere Huldigung.

The Nobel Foundation's copyright has expired.Emil von Behring: The founder of serum therapy

Emil von Behring: The founder of serum therapy

Based on an exhibition at Marburg Castle

arranged and documented by Kornelia Grundmann*

This article was published on 3 December 2001.

Upbringing and education

Emil Behring (1854-1917) was born on March 15, 1854 in Hansdorf, West Prussia, as the first child of the couple August and Auguste Behring. His father was a village school teacher, who during his first marriage had had four children and after the birth of Emil had another eight children.

A talented pupil, Emil Behring was above all assisted by the village minister, who made it possible for him to attend the Gymnasium (High School) in the village Hohenstein. His orientation as a theology student appeared to have changed after a friend who was a military doctor arranged for him to start his medical studies at the University of Berlin. He obtained a scholarship and from 1874 through 1878 he studied at the Academy for Military Doctors at the Royal Medical-Surgical Friedrich-Wilhelm-Institute, where he also earned his medical degree. In the following years he had to perform as a military doctor and also worked as a troop doctor in various garrisons. After having been assigned as captain of the medical corps to the Pharmacological Institute at the University of Bonn, he was given a position at the Hygiene Institute of Berlin in 1888 as an assistant to Robert Koch (1843-1910), one of the pioneers of bacteriology. During this time, Behring’s first authoritative publication on diphtheria and tetanus serum therapy appeared.

Emil von Behring in a military uniform.

The Behring family

During his early years as a military doctor, Behring’s income was not sufficient for him to think about starting a family. Only in 1896, when he had a regular salary, did he marry the 20 year old Else Spinola. They went on a three-month honeymoon to the island of Capri. Else, born August 30, 1876 in Berlin, was the daughter of Werner Spinola, Administrative Director of Charité, the university medical clinic in Berlin.

In 1898, after having become professor at the University in Marburg (then part of Prussia), Behring moved with his family into a house in Wilhelm-Roser-Strasse in Marburg, where his six sons were born. Behring was a family man, though rather patriarchal, which at that time was quite normal. In the circle of his family he felt content, although his scientific work presumably did not leave him much time for his wife and children.

Wedding picture of Emil and Else von Behring.

On March 31, 1917, Behring died and was entombed in a mausoleum at the Marburg Elsenhöhe. After Behring’s death, Else von Behring served as chairwoman of the Women’s National Organisation in Marburg, Germany. She died in 1936 of a heart attack at the age of only 59.

Family and friends

On the list of his sons’ godfathers, it appears obvious who stood closest to Emil von Behring besides his family. His first son, Fritz, had the bacteriologist Friedrich Loeffler (1852-1915) and Behring’s friend and co-worker, Erich Wernicke as godfathers. The godfather of his third son, Hans, was the Prussian Under-Secretary of Education and Cultural Affairs, Friedrich Althoff. His fifth son, Emil, had as a godfather the Russian researcher Elias Metschnikoff (1845-1916), founder of the theory of phagocytosis, with whom Behring had continuous scientific exchange of ideas. Emil’s second godfather was the pupil of Louis Pasteur, Émile Roux (1853-1933), who like Behring Sr. dealt with the fight against diphtheria. In 1913, the godfather of his sixth son, Otto, was the physician Ludolph Brauer (1865-1951), who had taught together with Behring at the Marburg Medical Faculty as a professor of internal medicine.

The development of the diphtheria-therapeutic-serum

Behring, who in the early 1890s became an assistant at the Institute for Infectious Diseases, headed by Robert Koch, started his studies with experiments on the development of a therapeutic serum. In 1890, together with his university friend Erich Wernicke, he had managed to develop the first effective therapeutic serum against diphtheria. At the same time, together with Shibasaburo Kitasato he developed an effective therapeutic serum against tetanus.

Behring together with his colleagues Wernicke (left) and Frosch (center) in Robert Koch’s laboratory in Berlin.

The researchers immunized rats, guinea pigs and rabbits with attenuated forms of the infectious agents causing diphtheria and alternatively, tetanus. The sera produced by these animals were injected into non-immunized animals that were previously infected with the fully virulent bacteria. The ill animals could be cured through the administration of the serum. With the blood serum therapy, Behring and Kitasato firstly used the passive immunization method in the fight against infectious diseases. The particularly poisonous substances from bacteria – or toxins – could be rendered harmless by the serum of animals immunized with attenuated forms of the infectious agent through antidotes or antitoxins.

Shibasaburo Kitasato.

The introduction of serum therapy

The first successful therapeutic serum treatment of a child suffering from diphtheria occurred in 1891. Until then more than 50,000 children in Germany died yearly of diphtheria. During the first few years, there was no successful breakthrough for this form of therapy, as the antitoxins were not sufficiently concentrated. Not until the development of enrichment by the bacteriologist Paul Ehrlich (1854-1915) along with a precise quantification and standardization protocol, was an exact determination of quality of the antitoxins presented and successfully developed. Behring subsequently decided to draw up a contract with Ehrlich as the foundation of their future collaboration. They organized a laboratory under a railroad circle (Stadtbahnbogen) in Berlin, where they could then obtain the serum in large amounts by using large animals – first sheep and later horses.

In 1892, Behring and the Hoechst chemical and pharmaceutical company at Frankfurt/Main, started working together, as they recognized the therapeutic potential of the diphtheria antitoxin. From 1894, the production and marketing of the therapeutic serum began at Hoechst. Besides many positive reactions, there was also noticeable criticism. Resistance, however, was soon put aside, due to the success of the therapy.

The Marburg years

Behring was given the opportunity to start a university career through one of the leading officers (Ministerialrat) of the Prussian Ministry of Education and Cultural Affairs, Friedrich Althoff (1839-1908), who wanted to improve the control of epidemics in Prussia by supporting bacteriological research. After a short period as professor at the University of Halle-Wittenberg, Behring was recruited by Althoff to take over the vacant chair in hygiene at Philipps Marburg University on April 1, 1895. His appointment as full professor followed shortly thereafter against the will of the faculty, who besides all of Behring’s outstanding discoveries, wanted a university lecturer who would broadly represent the field. However, Althoff rejected all counterproposals and Behring took over as Director of the Institute of Hygiene at Marburg. His position included giving lectures for hygiene and concurrently held a teaching contract in the history of medicine. In 1896, the Marburg Institute of Hygiene moved to a building on a road nearby Pilgrimstein Road, previously the Surgery Clinic. Behring divided the Institute into two departments, a Research Department for Experimental Therapy and a Teaching Department for Hygiene and Bacteriology. He remained Director of the Institute until his retirement as professor in May 1916.

Scientific contacts

Behring belonged to a scientific discussion group called “The Marburg Circle” (das Marburger Kränzchen), whose other members were the zoologist Eugen Korschelt (1858-1946), the surgeon Paul Friedrich (1864-1916), the botanist Arthur Meyer (1850-1922), the physiologist Friedrich Schenk (1862-1916), the pathologist Carl August Beneke (1861-1945) and the pharmacologist August Gürber (1864-1937). They often met at Behring’s home where they had rounds of vivid and prolific scientific discussions.

Active protective vaccination against diphtheria

Old vials (1897 and 1906) with hand-written labels.

The therapeutic serum developed by Behring prevented diphtheria for only a short period of time. In 1901, Behring, therefore, for the first time, used a diphtheria innoculation of bacteria with reduced virulence. With this active immunization he hoped to help the body also produce antitoxins. As a supporter of the humoral theory of immune response, Behring believed in the long-term protective action of these antitoxins found in serum. It is well-established knowledge today that active vaccination stimulates the antitoxin (antibody) producing cells to full function.

The development of an active vaccine took a few years. In 1913, Behring went public with his diphtheria protective agent, T.A. (Toxin-Antitoxin). It contained a mixture of diphtheria toxin and therapeutic serum antitoxin. The toxin was meant to cause a light general response of the body, but not to harm the person who is vaccinated. In addition, it was designed to provide long-term protection. The new drug was tested at various clinics and was proven to be non-harmful and effective.

Tetanus therapeutic serum during World War I

In 1891, tetanus serum was introduced considerably more quickly in clinical practices than the diphtheria serum. The Agricultural Ministry supported research efforts to develop a therapeutic agent against tetanus to protect agriculturally valuable animals. The large amounts of serum required were obtained through the immunization of horses. However, there was no substantial clinical testing on humans; this led the Military Administration to accept it only on a small scale at the beginning of World War I.

During the first months of the war, this restraint led to massive losses of human lives. Also, after the distribution of the tetanus antitoxins in the military hospitals, many futile attempts at therapy were noted. At the end of 1914, as a result of Behring’s constructive assistance, the injection of serum was established as preventing disease. Starting in April 1915, the mistakes in dosage and the shortage of supplies were overcome and the numbers of sick fell dramatically. Behring was declared “Saviour of the German Soldiers” and was awarded the the Prussian Iron Cross medal.

Historical engraving showing how the medicinal serum was obtained from immunized horses.

An attempt to develop a therapeutic method against tuberculosis

After Robert Koch had failed with his tuberculosis therapy in 1893, Behring began to search for an effective therapeutic agent against this disease. However, very soon, he had to admit that combating tuberculosis using a healing serum was not feasible. Therefore, he concentrated on working on a preventive vaccination, which, however, required precise knowledge of the mechanism of infection. In Behring’s view, the tubercle bacillus was transmitted to children through the milk of a mother or a cow infected with tuberculosis. He then started treating milk with formaldehyde, so as to eliminate this source of infection. This procedure was not accepted due to the bad smell of the milk. Moreover, the transmission of tubercle bacilli through the respiratory tract was proven to be more likely than through the digestive system, as had been claimed by Behring.

From 1903, Behring worked on active immunization through attenuated tuberculosis infectious agents, which he then tried on cows, however, with only moderate success. His aim was to obtain a protective and therapeutic agent for humans. A number of agents (tuberculase, tulase, tulaseactin, tulon) failed to make a breakthrough. At the beginning of World War I, Behring halted his efforts to combat tuberculosis and dedicated himself entirely to the further development of tetanus serum.

Behring’s relationship to Paul Ehrlich

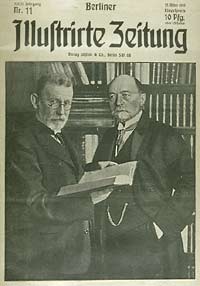

Paul Ehrlich was Behring’s colleague at Robert Koch’s institute. Here, he was able to work out a reliable and reproducible standardization method for diphtheria serum. However, in later years, tension developed between the two researchers. Differences with Ehrlich’s pupil, Hans Aronson, resulted in bad feelings, which increased when Ehrlich’s Royal Institute of Experimental Therapy was founded at Frankfurt/Main. The previous friendship between the two researchers never fully succumbed, through the mediation of Friedrich Althoff. However, it was subsequently demonstrated that the only photograph showing Behring and Ehrlich together, which appeared on the cover of a Berlin newspaper on the occasion of their 60th birthday in 1914, was a photomontage made up of two separate photographs.

Report of the Berliner Illustrirte Zeitung (Berlin Illustrated Newspaper) about Emil von Behring and Paul Erlich and their work on the occasion of their 60th birthday.

Behring’s health

Behring lived entirely for his idea of revolutionizing medicine through serum therapy. This idea hung above him and motivated him, in his own words, “like a demon.” His enormous concentration on his work often drove him to physical illnesses, as well as to deep depressions, which forced him to take time off work for a sanatorium stay from 1907 through 1910.

Acknowledgements and honors

In 1903, Emil von Behring was given the title of “Wirklicher Geheimer Rat mit dem Prädikat Excellenz” by the German emperor Wilhelm II. The diploma says: “This is in order that Behring should remain in unbroken loyalty to Myself and the Royal Family and to fulfill his official responsibility with continuous eagerness, whereby he who has the right connected to his present character, will receive the highest protection by Myself”. A splendid uniform was provided along with the title.

In 1901, when the Nobel Prizes were awarded for the first time, Behring received the Prize in Physiology or Medicine.

A detail (right) and the diploma for the first Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine, awarded to Behring in 1901.

Behring jubilee in 1940

On December 4, 1940, the Philipps University Marburg celebrated the 50th anniversary of the original publication of Emil von Behring’s decisive discovery of serum therapy. Top leaders of the National Socialist Party, the rectors of numerous German universities, representatives of the Behringwerke and many scientists and friends of Emil von Behring from abroad were also present. The celebration, which continued over a few days, began with lectures and addresses by officials, both of the state and party. Finally, a foundation certificate for a new Institute for Experimental Therapy was handed over. The professors then moved from the university auditorium (Aula), to unveal a new Behring Memorial close to the St. Elisabeth Church. The celebration was followed by a two-day scientific meeting, presenting the state of the art of immunology and the fight against infectious diseases.

The background of the celebration

In the view of the National Socialists, Else von Behring was regarded as a “half-Jew”, as her mother came from a Jewish family. With the help of a number of friends she was able to get her sons accepted by Hitler as “Aryans” and not stigmatized as “half-breeds”. After the death of Else von Behring in 1936, no obstacles were left for the Nazi party to use Emil von Behring as a glorified representative of national socialist “Germanic” science. During the ceremony there were, however, some signs of tension. Although one of Behring’s sons participated in the ceremony, he was not greeted by any of the official speakers. Only the Danish researcher, Thorvald Madsen from Copenhagen, who had previously been chairman of the Health Organisation of the League of Nations, dared to mention Behring’s friendly connection with researchers from enemy countries, such as those at the Institut Pasteur in Paris. Courageously, he also recalled the great bacteriologist Paul Ehrlich, despised by the Nazis due to his Jewish origin, who had played a significant role in Behring’s successes.

Translated by Gabriella Nichols, Department of Anatomy, Philipps University Marburg, Germany.

* The exhibition was from October to December 2001.

Kornelia Grundmann (b. 1951) studied biology, biochemistry and medicine at the Free University of Berlin and worked for close to ten years in biomedical research. Subsequently she moved to Marburg and began research in the history of medicine focusing on the 19th and 20th century (anatomy, bacteriology and psychiatry). In particular, she has studied the development of the medical faculty of Marburg during the Third Reich and the postwar period.

Dr Grundmann is curator of the Behring Archives at the Behring Library for History and Ethics of Medicine and the Anatomical Museum of the Phillips University, Marburg, Germany.

First published 3 December 2001

Emil von Behring – Other resources

Links to other sites

Emil von Behring – Biographical

Emil Adolf Behring was born on March 15, 1854 at Hansdorf, Deutsch-Eylau as the eldest son of the second marriage of a schoolmaster with a total of 13 children. Since the family could not afford to keep Emil at a University, he entered, in 1874, the well-known Army Medical College at Berlin. This made his studies financially practicable but also carried the obligation to stay in military service for several years after he had taken his medical degree (1878) and passed his State Examination (1880). He was then sent to Wohlau and Posen in Poland. Besides much practical work he found in Posen time to study (at the Chemical Department of the Experimental Station) problems connected with septic diseases. In the years 1881-1883 he carried out important investigations on the action of iodoform, stating that it does not kill microbes but may neutralize the poisons given off by them, thus being antitoxic. His first publications on these questions appeared in 1882. The governing body concerned with military health, which was especially interested in the prevention and combating of epidemics, being aware of the ability of Behring, sent him to the pharmacologist C. Binz at Bonn for further training in experimental methods. In 1888 they ordered him back to Berlin, where he worked-undoubtedly in full agreement with his own wishes – as an assistant at the Institute of Hygiene under Robert Koch. He remained there for several years after 1889, and followed Koch when the latter moved to the Institute for Infectious Diseases. This appointment brought him into close association, not only with Koch, but also with P. Ehrlich, who joined, in 1890, the brilliant team of workers Koch had gathered round him. In 1894 Behring became Professor of Hygiene at Halle, and the following year he moved to the corresponding chair at Marburg.

Behring’s most important researches were intimately bound up with the epoch-making work of Pasteur, Koch, Ehrlich, Löffler, Roux, Yersin and others, which led the foundation of our modern knowledge of the immunology of bacterial diseases; but he is, himself, chiefly remembered for his work on diphtheria and on tuberculosis. During the years 1888-1890 E. Roux and A. Yersin, working at the Pasteur Institute in Paris, had shown that filtrates of diphtheria cultures which contained no bacilli, contained a substance which they called a toxin, that produced, when injected into animals, all the symptoms of diphtheria. In 1890, L. Brieger and C. Fraenkel prepared, from cultures of diphtheria bacilli, a toxic substance, which they called toxalbumin, which when injected in suitable doses into guinea-pigs, immunized these animals to diphtheria.

Starting from his observations on the action of iodoform, Behring tried to find whether a disinfection of the living organism might be obtained if animals were injected with material that had been treated with various disinfectants. Above all the experiments were performed with diphtheria and with tetanus bacilli. They led to the well-known development of a new kind of therapy for these two diseases. In 1890 Behring and S. Kitasato published their discovery that graduated doses of sterilised brothcultures of diphtheria or of tetanus bacilli caused the animals to produce, in their blood, substances which could neutralize the toxins which these bacilli produced (antitoxins). They also showed that the antitoxins thus produced by one animal could immunize another animal and that it could cure an animal actually showing symptoms of diphtheria. This great discovery was soon confirmed and successfully used by other workers.

Earlier in 1898, Behring and F. Wernicke had found that immunity to diphtheria could be produced by the injection into animals of diphtheria toxin neutralized by diphtheria antitoxin, and in 1907 Theobald Smith had suggested that such toxin-antitoxin mixtures might be used to immunize man against this disease. It was Behring, however, who announced, in 1913, his production of a mixture of this kind, and subsequent work which modified and refined the mixture originally produced by Behring resulted in the modern methods of immunization which have largely banished diphtheria from the scourges of mankind. Behring himself saw in his production of this toxin-antitoxin mixture the possibility of the final eradication of diphtheria; and he regarded this part of his efforts as the crowning success of his life’s work.

From 1901 onwards Behring’s health prevented him from giving regular lectures and he devoted himself chiefly to the study of tuberculosis. To facilitate his work a commercial firm in which he had a financial interest, built for him well-equipped laboratories at Marburg and in 1914 he himself founded, also in Marburg, the Behringwerke for the manufacture of sera and vaccines and for experimental work on these. His association with the production of sera and vaccines made him financially prosperous and he owned a large estate at Marburg, which was well stocked with cattle which he used for experimental purposes.

The great majority of Behring’s numerous publications have been made easily available in the editions of his Gesammelte Abhandlungen (Collected Papers) in 1893 and 1915.

Numerous distinctions were conferred upon Behring. Already in 1893 the title of Professor was conferred upon him, and two years later he became «Geheimer Medizinalrat» and officer of the French Legion of Honour. In the ensuing years followed honorary membership of Societies in Italy, Turkey and France; in 1901, the year of his Nobel Prize, he was raised to the nobility, and in 1903 he was elected to the Privy Council with the title of Excellency. Later followed further honorary memberships in Hungary and Russia, as well as orders and medals from Germany, Turkey and Roumania. He also became an honorary freeman (Ehrenbürger) of Marburg.

In 1896 Behring married the 20 years old Else Spinola, daughter of the Director of the Charité at Berlin. They had six sons. Behring died at Marburg on March 31, 1917.

This autobiography/biography was written at the time of the award and first published in the book series Les Prix Nobel. It was later edited and republished in Nobel Lectures. To cite this document, always state the source as shown above.

The Nobel Foundation's copyright has expired.