Alphonse Laveran – Nominations

Alphonse Laveran – Facts

Award ceremony speech

Presentation Speech by Professor C. Sundberg, member of the Staff of Professors of the Royal Caroline Institute, on December 10, 1907*

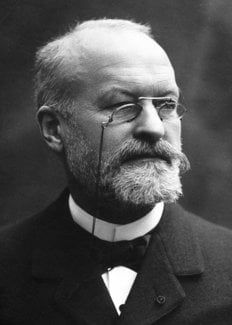

The Staff of Professors at the Caroline Institute have this year awarded the Nobel Prize for Medicine to Dr. Charles Louis Alphonse Laveran, for his work on the importance of the protozoa as pathogens.

The Staff has thus chosen to single him out not only as the founder of medical protozoology, a branch of medicine that has reached a striking level of development in recent years; but also as the man responsible for experiments and discoveries – followed up until recently – which ensure his continued pre-eminence in this field.

To appreciate properly the importance of Laveran’s investigations into the protozoan causes of disease, one must remember the state of this branch of science at the time of Laveran’s earliest work, i.e. about 1880. The body of knowledge relating to the causes of infectious diseases was making rapid progress at that time in the field of bacteriology. Pasteur’s «Theory of Germs» had provided the key to the riddle of fermentation processes, and its relevance to infectious diseases had been grasped. So several pathogenic bacteria had been discovered by 1880: those of anthrax and relapsing fever; other germs, such as those causing tuberculosis, glanders, pneumonia, typhoid fever, diphtheria, tetanus, Asiatic cholera, traumatic fevers, etc. were discovered one after another during the years 1880-90. All these germs were found to belong to the last category of the plant kingdom, the bacteria.

As a result, it was natural to look for the cause of marsh fevers, like malaria, among micro-organisms of that sort. Indeed, several distinguished bacteriologists believed themselves to be on the trail of such a microbe. We recall the so-called malaria bacillus of Klebs and Tommasi-Crudeli, found in the ooze of the Pontine Marshes.

When Laveran, in 1879, began his research at the military hospital of Bône in Algeria, he only set himself the task of explaining the role of the particles of black pigment found in the blood of people suffering from malaria. After 1850, when these particles, called melanins, were discovered, methods had been discussed of determining whether they were only to be found in patients suffering from malaria, or were present in other diseases as well. Laveran first set about solving this problem, which was particularly important to the diagnosis of malaria. During his investigations, Laveran not only found the particles he had been looking for: he also found some entirely unknown bodies with certain characteristics which led him to suppose that parasites were involved. His initial investigations were carried out on fresh blood without using chemical reactions or any staining process. He was none the less successful, using this primitive method of examination, in distinguishing and describing most of the more important forms adopted by these new bodies, which varied so much in their appearance. In 1882, he moved the scene of his investigations for a while to the dangerous marshy regions of Italy. There he again found the same bodies in the blood of people suffering from marsh fever, and his hope of having found the malarial parasite became a certainty. Laveran published his first great work on these parasites, Traité des fièvres palustres, in 1884. In this, he draws on 480 examined cases of malaria.

This work is the foundation on which subsequent investigations of marsh fever are based. Laveran showed that the parasites, during their development in the red blood corpuscles, destroy them; and the red pigment in the corpuscles is changed into the melanin particles mentioned above. He described all the main forms of this polymorphic parasite, even those which have subsequently been found to be different developmental phases of the parasite. Continuing his work, Laveran concerned himself in the first place with the important problem of the existence of these parasites outside the patient’s body. To this end he examined the water, soil, and air of the marshlands, hoping to find the parasite. His perseverance was unrewarded. We should not, however, fail to recognize the merit of this work, despite its negative outcome, since it has fundamentally aided subsequent research. As far as Laveran was concerned, these apparently fruitless investigations led him to the conclusions which he expresses in the book of 1884, and has also maintained on a number of occasions, such as the Congress of Hygiene at Budapest (1894): that the marsh-fever parasite must undergo one phase of its development in mosquitoes, and be inoculated into humans by their bites. Laveran based his conclusion not only on the negative experiments already mentioned, but also on an analogy with the mode of transmission of the Filaria worm, which, according to Manson, is mosquito-borne. When Laveran was recalled from Algeria to Paris, and so forced to interrupt his work on malaria, he had already clearly formulated the problems that had first to be solved in this field.

The new parasite discovered by Laveran was not a bacterium. Although it was impossible to classify accurately, certain resemblances to other micro-organisms put it in the same group as the protozoa. We know how difficult it is to demonstrate the presence of malarial parasites in blood which has not been treated beforehand with the stains now in general use, but still unknown at the time of Laveran’s discoveries, which make these small parasites more readily visible; so one can appreciate at their true value the insight and keen eye of Laveran, who never allowed himself to be misled by the simultaneous successes of bacteriology, or discouraged by the opposition met with from several quarters, notably from workers studying marsh fever.

However, little by little Laveran’s theories made headway, and it can be said that the year 1889 marks the date when his discovery finally achieved recognition.

When Laveran had to leave the marshlands, he saw himself deprived of materials indispensable if he were to continue working on the still unanswered questions, i.e. those dealing with the parasite’s developmental cycle, and its existence away from the patient. He then tried to solve them by an indirect approach, by studying animal parasites, especially those of birds: these parasites had only recently been discovered and showed resemblances to the malarial parasites. The numerous observations Laveran made in the course of this research cannot be indicated here: they belong by rights to the specialist sphere of interest. Now, as always happens after a notable discovery, workers multiplied in the new field. Some of the many workers who were able to continue Laveran’s work on the spot, in marshy areas, were destined to reach the goal before Laveran by the indirect approach which he had indicated. Thus, in 1897 the American Mac Callum elucidated the sexual reproduction of these parasites; and, in 1898, the impressive work of Ronald Ross, the Nobel Prize winner for 1902, brought the mosquito theory from the realm of hypothesis into that of established fact. One can imagine the interest with which Laveran must have received the preparations sent to him by Ross from India in May 1898, and the joy with which he confirmed that Ross was in fact dealing with malaria parasites in the mosquitoes he was investigating.

Laveran’s discoveries concerning malaria had the additional effect of focussing direct and vigorous attention on the hypothesis that other infectious diseases could be brought about similarly by protozoa. In the tropics especially, but in other areas as well, diseases have been recognized for a long time among men and animals, which are similar to malaria in many respects, such as impoverishment of the blood, loss of strength, and associated fever, but which, unlike malaria, are not affected by the classical treatment, quinine, and are clearly shown by the absence of marsh-fever parasites not to belong to the same group as the marsh sicknesses. Since 1890 a whole series of parasites causing these diseases has been described. Once, thanks to Laveran, attention was drawn to the protozoa as agents of disease, discoveries of such protozoa took place in rapid succession. Among diseases due to protozoa, the trypanosomiases take precedence. The list of these diseases alone is long, and we will mention only the scourges known as Nagana, Surra, Caderas sickness, and the Galziekte of Equatorial Africa, etc. which ravage large parts of Africa, Asia and South America, attacking various members of the Bovidae, horses, camels, donkeys, etc. as well as the big game, antelopes, deer, etc. sometimes wiping out great herds. All these infections are caused by corkscrew-shaped micro-parasites, called trypanosomes, and are transmitted to animals by various types of biting flies. However important these diseases may be to Man from the point of view of commerce and nutrition, yet, among all the trypanosomiases, the endemic disease generally known as «sleeping-sickness» takes precedence from the medical point of view. The sleeping-sickness trypanosome was discovered in 1901 by Forde in a European ship’s captain who had navigated the river Gambia for several years. Forde does not seem to have examined the parasite in detail. Later, the same case was studied by Dutton, and following on his reports on the parasite and the disease, an expedition was sent from Liverpool and London to carry the investigation further. This expedition also solved the first problems relating to the disease. There is certainly much one could say about these diseases; unfortunately we may not dwell on them here. Let us rather take a quick look at the part played by Laveran in the elucidation of these problems.

It can be said, it seems to us, that Laveran took up these problems again at the exact point where circumstances had forced him to interrupt his own research on malaria. He had discovered the parasites for the latter group of diseases, but others, notably Golgi and Ross, followed up the biological investigation of the parasites. As far as the trypanosomiases are concerned, the opposite holds good: the parasites were discovered by other investigators, who were able to study the investigations on the spot in a number of different places, but Laveran, more than anyone else, extended our understanding of the finer points of the morphology, biology, and pathological activity of the parasites. He made this work possible by having many artificially-infected experimental animals brought to his Paris laboratory, as well as larger animals which had contracted the disease naturally. Not content with this great quantity of material, he extended the scope of his investigations even further by studying the trypanosomes of rats, birds, fishes and reptiles; and these investigations often threw light on the true pathogenic trypanosomes at the same time. The trypanosomes thus studied and described by Laveran number about thirty; he discovered a greater number of new species than any other worker we know of. In addition, he discovered a new genus of trypanosomes, the trypanoplasmias.

Laveran published his discoveries, sometimes in collaboration with other workers, in many articles and annotations, and later, in 1904, he gathered them together in one great work, so far unique of its kind: Les trypanosomes et trypanosomiasis.

Still more recently, in 1906, there appeared the accounts of his research on the parasites causing the malignant Mbori, Souma, and Baléri diseases, which are widespread among the Bovidae, camels and horses of the Upper Niger.

It is obviously impossible to compress into a few words the rich content of all his writings, his investigations, and his numerous discoveries. In them we find technical inventions for the study of parasites, morphology, theories of infection, accounts of parasite reproduction, experiments in immunization, etc. These works are proof that the creator of protozoan pathology continues to be its leading authority. For these reasons and many others that could be added, the Staff of Professors of the Caroline Institute have pleasure in awarding this year’s Nobel Prize to this pioneer of science, this tireless benefactor of humanity.

* Owing to the decease of King Oscar II two days earlier, the presentation ceremony had to be cancelled. The speech, of which the text is rendered here, was therefore not delivered orally.

The Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine 1907

Alphonse Laveran – Biographical

Charles Louis Alphonse Laveran was born in Paris on June 18, 1845 in the house which was formerly No. 19 rue de l’Est but later became, when this district was rebuilt, an hotel at No. 125, Boulevard St. Michel.

Both his father and paternal grandfather were medical men. His father, Dr. Louis Théodore Laveran, was an army doctor and a Professor at the École de Val-de-Grâce, his mother, née Guénard de la Tour, was the daughter and granddaughter of high-ranking army commanders. When he was very young, Alphonse went with his family to Algeria. His father returned to France as Professor at the École de Val-de-Grâce, of which he became Director with the rank of Army Medical Inspector.

Alphonse, after completing his education in Paris at the Collège Saint Baube and later at the Lycée Louis-le-Grand, wished to follow his father’s profession and in 1863 he applied to the Public Health School at Strasbourg, was admitted there and attended the courses for four years. In 1866 he was appointed as a resident medical student in the Strasbourg civil hospitals. In 1867 he submitted a thesis on the regeneration of nerves. In 1870, when the Franco-German war broke out, he was a medical assistant-major and was sent to the army at Metz as ambulance officer. He took part in the battles of Gravelotte and Saint-Privat and in the siege of Metz. After the capitulation of Metz, he went back to France and was attached first to Lille hospital and then to the St. Martin Hospital in Paris. In 1874 he was appointed, after competitive examination, to the Chair of Military Diseases and Epidemics at the École de Val-de-Grâce, previously occupied by his father. In 1878, when his period of office had ended, he was sent to Bône in Algeria and remained there until 1883. It was during this period that he carried out his chief researches on the human malarial parasites, first at Bône and later at Constantine.

In 1882, he went to Rome with the special aim of seeking, in the blood of patients who had become infected with malaria in the Roman Campagna, the parasites he had found in the blood of patients in Algeria. His researches, done at the San Spirito Hospital, confirmed him in the opinion that the blood parasites that he had described were in fact the cause of malaria. His first communications on the malaria parasites were received with much scepticism, but gradually confirmative researches were published by scientists of every country and, in 1889, the Academy of Sciences awarded him the Bréant Prize for his discovery, which was from that time not disputed, of the malarial parasites. In 1884, he was appointed Professor of Military Hygiene at the École de Val-de-Grâce.

In 1894, his period of office as professor having ended, he was appointed Chief Medical Officer of the military hospital at Lille and then Director of Health Services of the 11th Army Corps at Nantes. He had neither a Laboratory nor patients, but he wished to continue his scientific investigations. He now held the rank of Principal Medical Officer of the First Class and in 1896 he entered the Pasteur Institute as Chief of the Honorary Service. From 1897 until 1907, he carried out many original researches on endoglobular Haematozoa and on Sporozoa and Trypanosomes. In 1907 he was awarded the Nobel Prize for his work on protozoa in causing diseases and he gave half the Prize to found the Laboratory of Tropical Medicine at the Pasteur Institute. In 1908 he founded the Société de Pathologie Exotique, over which he presided for 12 years. He did not abandon his interest in malaria. He visited the malarious areas of France (the Vendée, Camargue and Corsica). He was the first to express the view that the malarial parasite must be found, outside the human body, as a parasite of Culicidae and, after this view had been proved by the patient researches of Ronald Ross, he played a large part in the enquiry on the relationships between Anopheles and malaria in the campaign undertaken against endemic disease in swamps, notably in Corsica and Algeria.

Since 1900, he especially studied the trypanosomes and published either independently or in collaboration with others, a large number of papers on these blood parasites. He successively studied: the trypanosomes of the rat, the trypanosomes that cause Nagana and Surra, the trypanosome of horses in Gambia, a trypanosome of cattle in the Transvaal, the trypanosomiases of the Upper Niger, the trypanosomes of birds, Chelonians, Batrachians and Fishes and finally and especially the trypanosome which causes the terrible endemic disease of Equatorial Africa known as sleeping sickness. His work (not completed) on the treatment of trypanosomiases and especially on infections with Tr.gambiense have already had important results.

To sum up, Laveran did not, for 27 years, cease to work on pathogenic Protozoa and the field he opened up by his discovery of the malarial parasites has been increasingly enlarged. Protozoal diseases constitute today one of the most interesting chapters in both medical and veterinary pathology.

Laveran was, in 1893, elected a Member of the Academy of Sciences. He also became, in 1912, a Commander of the Legion of Honour. During the years 1914-1918, he took part in all the committees concerned with the maintenance of the good health of the troops, visiting Army Corps, compiling reports and appropriate instructions. He was a member, associate or honorary member of a vast number of learned societies in France, Great Britain, Belgium, Italy, Portugal, Hungary, Rumania, Russia, the U.S.A., the Netherlands Indies, Mexico, Cuba and Brazil.

In 1885 he married Mlle. Pidancet. On May 18, 1922, he died after an illness lasting several months.

This autobiography/biography was written at the time of the award and first published in the book series Les Prix Nobel. It was later edited and republished in Nobel Lectures. To cite this document, always state the source as shown above.

The Nobel Foundation's copyright has expired.Alphonse Laveran – Nobel Lecture

Nobel Lecture, December 11, 1907

Protozoa as Causes of Diseases

My scientific colleagues of the Caroline Institute having done me the very great honour of awarding me the Nobel Prize in Medicine this year for my work on diseases due to Protozoa, the regulations of the Nobel Foundation oblige me to give a summary of my main researches on this question.

I must however go back a little in order to explain how I was led to concern myself with the pathogenic protozoa.

In 1878 after having finished my course of instruction at the School of Military Medicine of Val-de-Grâce, I was sent to Algeria and put in charge of a department of the hospital at Bone. A large number of my patients had malarial fevers and I was naturally led to study these fevers of which I had only seen rare and benign forms in France.

Malaria which is almost unknown in the north of Europe is however of great importance in the south of the Continent particularly in Greece and Italy; these fevers in many of the localities become the dominant disease and the forms become more grave; alongside the intermittent forms, both the continuous forms and those called malignant appear. In the tropical and subtropical regions, endemic malaria takes first place almost everywhere among the causes of morbidity and mortality and it constitutes the principal obstacle to the acclimatization of Europeans in these regions. Algeria has become much less unhealthy than it was at the commencement of the French occupation but one still comes across regions such as the banks of Lake Fezzara, not far from Bone, in which endemic-epidemic malaria rages every year.

I had the opportunity of making necropsies on patients dead from malignant fever and of studying the melanaemia, i.e. the formation of black pigment in the blood of patients affected by malaria. This melanaemia had been described by many observers, but people were still in doubt about the constancy of the alteration in malaria, and about the causes of the production of this pigment.

I was struck by the special characters which these pigment grains presented especially in the capillaries of the liver and the cerebrospinal centres, and I tried to pursue the study of its formation in the blood of persons affected by malarial fever. I found in the blood, leucocytes more or less loaded with pigment, but in addition to these melaniferous leucocytes, pigmented spherical bodies of variable size possessing amoeboid movement, free or adherent to the red cells; non-pigmented corpuscles forming clear spots in the red cells; finally pigmented elements, crescentic in shape attracted my attention, and from then on I supposed they were parasites.

In 1880 at the Military Hospital at Constantine, I discovered on the edges of the pigmented spherical bodies in the blood of a patient suffering from malaria, filiform elements resembling flagellae which were moving very rapidly, displacing the neighbouring red cells. From then on I had no more doubts of the parasitic nature of the elements which I had found; I described the principal appearances of the malarial haematozoon in memoranda sent to the Academy of Medicine, the Academy of Sciences (1880-1882) and in a monograph entitled: Nature parasitaire des accidents de l’impaludisme, description d’un nouveau parasite trouvé dans le sung des malades atteints de fièvre palustre, Paris, 1881.

These first results of my researches were received with much scepticism.

In 1879, Klebs and Tommasi Crudeli had described under the name of Bacillus malariae, a bacillus found in the soil and water in malarial localities and a large number of Italian observers had published papers confirming the work of these authors.

The haematozoon which I gave as the agent of malaria did not resemble bacteria, and was present in strange forms, and in short it was completely outside the circle of the known pathogenic microbes, and many observers not knowing how to classify it found it simpler to doubt its existence.

In 1880, the technique of examination of the blood was unfortunately very imperfect, which contributed to the prolongation of the discussion relative to the new haematozoon and it was necessary to perfect this technique and invent new staining procedures to demonstrate its structure.

Confirmatory investigations at first rare, became more and more numerous; at the same time endoglobular parasites were discovered in different animals which closely resembled the haematozoon of malaria. In 1889, my haematozoon had been found in the majority of malarial regions and it was not possible to doubt any more either its existence or its pathogenic role.

Many observers before me had sought without success to discover the cause of malaria and I should also have failed if I had been content merely to examine the air, water, or the soil in malarial localities as had been done up till then, but I had taken as the basis of my investigations the pathological anatomy and the study in vivo of malarial blood and this is how I was able to reach my goal.

The malarial haematozoon is a protozoon, a very small protozoon since it lives and develops in the red blood cells which in man have a diameter of only 7 microns.

One can summarize the principal ways in which the parasite appears in human blood, as follows:

1. Small, rounded, non-pigmented elements, 1-2 microns in diameter, forming clear spots in the red cells. In stained preparations a nucleus can be detected in each of these small elements. Multiplication is by halving or by multiple division.

2. Amoeboid elements inside the red cells or adherent to their surface, of variable form and dimensions and containing blackish pigment. The largest of these elements are the size of leucocytes. In stained preparations a nucleus can be detected in each amoeboid body. The parasitized red cells change: become paler and increase in diameter, and finally disappear. The gravity and constancy of the anaemia produced by these parasites, which develop rapidly at the expense of the red cells, is thus explained. Multiplication is by multiple segmentation (rose petal or segmented body).

3. Crescentic-shaped bodies measuring 8-9 microns long which are more or less tapered at the ends; towards the middle a corona of grains of pigment can be seen surrounding a nucleus which can only be detected in heavily stained specimens.

4. Flagellae. When a preparation of malarial blood is examined during a feverish attack one can often see developing on the edges of the pigmented spherical bodies derived from the amoeboid or crescent-shaped bodies, very fine flagellae, 20-25 microns long. These flagellae move actively, displacing the neighbouring red cells, and end by becoming detached; and once free they lose themselves among the mass of red cells.

The role of these flagellae was still not decided when the researches of Simond, Schaudinn and Siedlecki showed that analogous elements are found in the Coccidia and that they are male elements destined to fertilize the female elements.

It has now been definitely proved that the haematozoon of malaria has, like the Coccidia, two forms of reproduction: asexual, represented by the segmented bodies, and sexual, the flagellae being the male elements.

A large number of observers have admitted the existence of several species of malarial haematozoa, but for my part I have always defended the unity of malaria and its haematozoon, and the postulated species described under the names of parasites of tropical malaria, aestivo-autumnal fever, tertian or quartan fever appear to me to constitute simple varieties of the same haematozoon.

After the discovery of the malarial parasite in the blood of the patients an important question still remained to be solved: in what state does the haematozoon exist outside the body and how does infection occur? The solution of this problem required long and laborious researches.

After having vainly attempted to detect the parasite in the air, the water, or the soil of malarial areas and trying to cultivate it in the most varied media, I became convinced that the microbe was already present outside the human body in a parasitic state and very probably as a parasite of mosquitoes.

I put forward this opinion in 1884 in my Traité des fièvres palustres (Treatise on paludal fevers) and I returned to it on several occasions.

In 1894, in a report to the International Congress of Hygiene at Budapest on the aetiology of malaria, I wrote: “The failure of attempts at culture have led me to believe that the microbe of malaria lives outside the body in the parasitic state and I suspect in the mosquitoes which are abundant in malarial areas and which already play a very important role in the propagation of filariasis.” This opinion on the role of mosquitoes was considered by most observers at this time as not very likely.

In 1892 two Italian authors who have since become great supporters of infection by mosquitoes wrote:”Laveran supposes that mosquitoes are the intermediate hosts of the malarial parasite. We must object that mosquitoes do not attack birds and in addition, that there are many healthy localities where mosquitoes are abundant. Apart from these objections Calandruccio has observed that the parasites of malaria die in the intestine of the mosquitoes without further development. Laveran’s opinion rests therefore without any foundation, and the hypothesis put forward by us that the parasites exist outside the body in the form of amides is confirmed.”1

King2 in America had suggested in 1883 that mosquitoes played a part in the aetiology of malaria but he did not know of my work on the haematozoon of malaria and could not specify what part the mosquitoes played, so that in saying that the mosquito acted as a temporary host of the malarial parasite I had obviously got closer to the problem than King had been able to do. I indicated clearly the route that it was necessary to follow to arrive at the goal; to seek out what became of the parasite in the body of mosquitoes which had sucked malarial blood.

Having left the malarial countries it was not possible for me to verify the hypothesis I had put forward on the role of mosquitoes, and it is to Dr. Ronald Ross that we owe the demonstration that the malarial haematozoon and the closely related Haemamoeba malariae of birds complete several phases of their evolution in the Culicidae and are propagated by these insects.

R. Ross whose excellent and patient investigations have been very justly rewarded by being given the Nobel Prize in Medicine in 1902, has been very willing to acknowledge in many of his papers that he had been usefully guided by my deductions and by those of P. Manson.

Today the transformations which the malarial parasite undergoes in mosquitoes of the genus Anopheles are well known and no further doubt is possible on the role these insects play in the propagation of malaria. I consider it is useless to insist on this as it has been very completely dealt with by R. Ross in a conference held here in 1902.

From 1899, my principal work on malaria has had as the object, the study of the Culicidae in their relation to malarial endemicity and of the rational prophylaxis of this dreadful malady.

I have studied the Culicidae of France and of the French colonies and I have been able to show in a series of annotations published at the Academy of Sciences, or at the Academy of Medicine, and at the Society of Biology that Anopheles can be found in all the malarial localities.

Dr. Battesti and I have demonstrated that Anopheles could be found in all the malarial localities of Corsica which had been considered free from these Culicidae.

On my suggestion leagues against malaria have been set up in Corsica and in Algeria. These leagues have already rendered great service, the principal aim which they have to strive for being to spread among the public the new ideas concerning the cause, the mode of transmission, and the rational prophylaxis of malaria.

This year I have published the second edition of my Traité du paludisme and in the Introduction I have been able to write: “Malaria, the history of which not long ago presented such obscurities, is today one of the best known diseases. The study of the clinical forms and the pathological changes has been completed and defined; the haematozoon which I described in 1880 has been recognized by all writers as the cause of malaria; its propagation by mosquitoes has been demonstrated, and now we are able to fight the malady by specific drug treatment and rational prophylaxis.”

I come now to the examination of my other work on the intracellular haematozoa, the number of which has increased continually since the discovery of Haemamoeba malariae.

As from 1889, I have classified the endoglobular haematozoa or Haemocytozoa in three genera: Haemamoeba, Piroplasma, Haemogregarina.

In the genus Haemamoeba, I have studied the haemamoebae of birds which closely resemble H. malariae and I have described several new species in Padda oryzivora, in a titmouse, in the partridge and the turkey.

In 1889, I studied with Nicolle P. bigeminum and P. ovis in the genus Piroplasma and described the forms of multiplication of these haematozoa.

In 1901, I described Piroplasma equi and in 1903, the bacilliform piroplasma of the Bovidae from preparations which had been sent to me by Mr. Theiler, a Transvaal veterinary surgeon.

In 1903 and 1904, Mesnil and I helped to make known, under the name of Piroplasma Donovani, the parasite of Kala-Azar discovered in India by Doctors Leishman and Donovan.

In the genus Haemogregarina, I studied the endoglobular parasites of Chelonians, Bactrachians, Saurians, Ophidia, and fishes.

I described the forms of endogenous multiplication of the haemogregarines of Chelonians and reported a series of new species.

From 1897 to 1900, I published either by myself or with the collaboration of Mesnil, a series of notes on the Sporozoa, properly so-called: Coccidia and Myxosporidia, of which I reported several new species, Sarcosporidia and Gregarines.

In recent years I have devoted myself to the study of the trypanosomes which are the cause of a large number of epizootics: Surra, Nagana, Dourine, Souma, etc.; the pathological importance of these parasites has increased especially since it has been shown that the grave endemic disease known in Equatorial Africa under the name of sleeping sickness, was produced by a trypanosome Tr. gambiense.

Trypanosomes are Protozoa, very different from the endoglobular haematozoa; they live in the free state in the plasma and not in a state of inclusion in the red cells or in other anatomical elements; they belong to the class of Flagellidae.

The body protoplasm of a trypanosome is generally fusiform and more or less tapered at the ends. When stained, two masses of chromatin can be seen: a large one towards the middle of the body, the nucleus; the other, small, situated usually near the posterior end, the centrosome. The flagella which starts from the centrosome and bounds the undulating membrane usually ends at the anterior extremity by a free portion which forms the flagellaproper.

I have published a large number of notes and memoranda on the trypanosomes, and in 1904, with Mesnil a monograph entitled: Trypanosomes et Trypanosomiases.

Among the original investigations carried out either by myself or in collaboration, I should like to mention: investigations on the structure of trypanosomes and of that of the Flagellidae in general; the agglutination of trypanosomes and the conditions which produce it; the differentiation of the trypanosomiases; the trypanosomes of rats, Tr. Lewisi, of Nagana, Tr. Brucei, of horses in the Gambia, Tr. dimorphon; of sleeping sickness Tr. gambianse, one affecting bovines in the Transvaal Tr. Theileri, on three new species pathogenic for equines and bovines of the Upper Niger, Tr. Cazalboui, Tr. Pecaudi, and Tr. soudanense; on new trypanosomes of birds, Chelonians, Bactracians or fishes.

As far as fishes are concerned Mesnil and I have established the existence not only of new species but of a new genus, Trypanoplasma.

Trypanoplasma have been found in the rudd, carp, and minnow. Their structure differs markedly from that of the trypanosomes as can be ascertained from well-stained specimens. The body protoplasm is generally crescentic; there are two chromatin masses, the larger one, the nucleus, on the side of the convexity, the other narrower, more deeply stained situated usually on the edge of the concavity, the centrosome. This gives rise to two flagellae, an anterior one which becomes free at once, and one which borders the undulating membrane and only becomes free at the posterior extremity.

I have published several notes on the distribution of the Glossinae (tsetse) in Equatorial Africa and of other biting flies capable of propagating the trypanosomiases.

Finally, I should mention a series of papers on the prophylaxis and treatment of diseases due to trypanosomes. In 1904, I showed that arsenious acid (in the form of sodium arsenite) produced excellent effects in infections due to Tr. gambiense; and in 1904 and 1905, I communicated several notes to the Academy of Sciences on the combined treatment of various trypanosomiases by arsenious acid and Trypan red. With this method of treatment I have had good results in mice, rats, dogs, and monkeys infected with Tr. Evansi, Tr. gambiense, Tr. equiperdum; unfortunately later investigations have shown that Trypan red is badly tolerated by man.

With Dr. Thiroux. I undertook new experiments aimed at investigating whether the combination of two different arsenical preparations would not give better results than the use of arsenious acid alone or atoxyl alone. The results which we obtained by combining atoxyl with arsenic trisulphide or arsenious iodide have been very satisfactory and we hope that this new drug treatment may be used in human trypanosomiasis or sleeping sickness which is raging at the present time among the natives of Equatorial Africa and of which there are more and more cases among Europeans.

To summarize: for twenty-seven years, I have not ceased to busy myself with the study of the parasitic Protozoa of man and animals and I can say, I believe without exaggeration, that I have taken an important part in the progress which has been made in this field.

Before the discovery of the malarial haemotozoon no pathogenic endoglobular haematozoon was known; today the Haemocytozoa constitute a family, important for the number of genera and species and also for the role some of these Protozoa play in human or veterinary pathology.

By directing the attention of doctors and veterinary surgeons to examination of the blood, study of the endoglobular haematozoa prepared the way for the discovery of the diseases due to trypanosomes which themselves also constitute a new and very important chapter in pathology.

The knowledge of these new pathogenic agents has thrown a strong light on a large number of formerly obscure questions. The progress attained shows once more how just is the celebrated axiom formulated by Bacon: “Bene est scire, per causas scire.”

1. G. Grassi and R. Feletti, Contribuz. allo studio dei parassiti malarici, Atti Accad. Sci. Naturali Catania, [4] 5 (1892).

2. King, Popular Sci. Monthly, Sept. (1883).

The Nobel Foundation's copyright has expired.