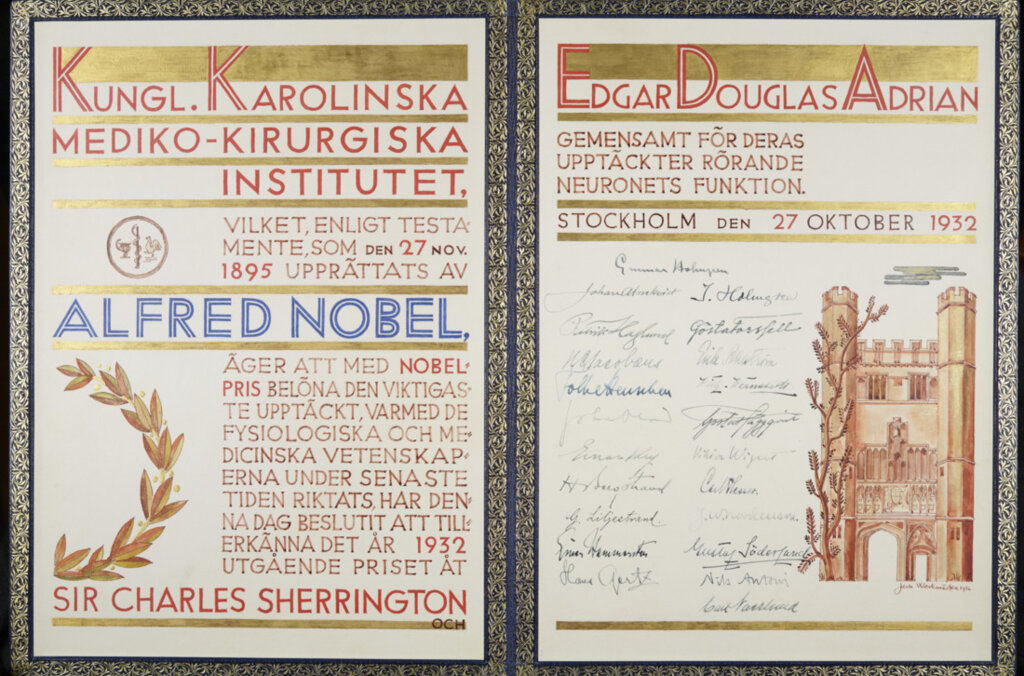

Edgar Adrian – Nobel diploma

Speed read: Network management

At any given time, our nervous system faces an enormous signal control task. Acting as the command centre for the entire body, it is charged with generating and processing the host of different messages sent through nerve cells that allow us to move, think and respond to any given stimulus. Managing this constant and complex network of signals relies on two basic principles formulated by the 1932 Nobel Laureates in Physiology or Medicine.

Charles Sherrington revealed how nerves co-ordinate movement by looking at simple reflexes; for instance, the way that a sharp tap on the knee causes the leg to jerk automatically and uncontrollably. By painstakingly examining thousands of these reflex pathways in animals, Sherrington showed how nerves inform muscles in limbs to contract or relax. Muscles contract when they are actively excited by signals coming from nerve cells, while muscles relax when nerve cells that control them are inhibited instead. Sherrington concluded that the interplay of these opposite excitatory and inhibitory signals generally coordinates and fine-tunes the postures and movements of our body, with each nerve cell somehow able to sum up the thousands of contradicting messages it receives and integrate them into one definite order issued within milliseconds.

More than two decades after Sherrington’s observations, Edgar Adrian used dramatically improved measurement techniques to decipher the form that this issued order takes in each nerve cell. Adrian dissected the breast muscle of frogs until it contained only one receptor that responds to a stimulus and a single nerve fibre, and he recorded and amplified the electrical impulses running through this fibre in response to touching or stretching the muscle. Amazingly, he discovered that the explosive waves of impulses discharged along the nerve are always the same size, regardless of how strong the stimulus is. As stronger stimulations only increase the number of impulses that are produced every second, Adrian deduced that nerve fibres must have an all-or-nothing response. If the electrical signal it receives reaches a certain threshold level at a particular time, a nerve fibre will respond by firing its impulse. If the threshold is not reached, there will be no firing order given out at all.

By Joachim Pietzsch, for Nobelprize.org

This Speed read is an element of the multimedia production “Nerve Signaling”. “Nerve Signaling” is a part of the AstraZeneca Nobel Medicine Initiative.

Edgar Adrian – Nobel Lecture

Nobel Lecture, December 12, 1932

The Activity of the Nerve Fibres

The sense organs respond to certain changes in their environment by sending messages or signals to the central nervous system. The signals travel rapidly over the long threads of protoplasm which form the sensory nerve fibres, and fresh signals are sent out by the motor fibres to arouse contraction in the appropriate muscles. What kind of signals are these, and how are they elaborated in the same organs and nerve cells? The first part of this question would have been answered correctly by most physiologists many years ago, but now it can be answered in much greater detail. It can be answered because of a recent improvement in electrical technique. The nerves do their work economically, without visible change and with the smallest expenditure of energy. The signals which they transmit can only be detected as changes of electrical potential, and these changes are very small and of very brief duration. It is little wonder therefore that progress in this branch of physiology has always been governed by the progress of physical technique and that the advent of the triode valve amplifier has opened up new lines in this, as in so many other fields of research.

I shall deal mainly with some of the results which have followed from this new technique, but the present state of our knowledge will be made clearer by a brief survey of the position as it was twenty years ago when I was a student in the Cambridge laboratories.

In the closing years of the last century the improvement of the capillary electrometer had marked a new phase. It was already known that some kind of rapid wave, called the nerve impulse, could be set up in the nerve by an electric stimulus, and there was good reason to suppose that the signals normally transmitted were made up of similar impulses. The disturbance due to an electric stimulus travelled at much the same rate as the natural signals, and it would produce similar effects on the muscles or on the central nervous system. It could be detected in the nerve by the change of potential which accompanied it; in fact Bernstein had already elaborated the “membrane hypothesis”which regards the impulse as a wave of surface disintegration spreading by reason of the electric disturbance which it creates. With the development of the capillary electrometer it became possible to make direct and accurate records of this electric disturbance. Before long the work of Gotch and Burch, Garten, Samojloff, and finally of Keith Lucas had given a detailed knowledge of its time relations and of its connection with the impulse. It was made clear that the wave of activity is invariably accompanied by a change of potential, that the activity at any point lasts only for a few thousandths of a second, and that it is followed by a refractory state which must pass away before another wave of activity can occur. The existence of a refractory period in the heart muscle had been recognized long before and its discovery in the nerve was of fundamental importance. It showed that the nerve fibre, when stimulated electrically, could only work in a succession of jerks separated by periods of enforced rest, and this was true both for the waves of potential change and for the underlying impulse which produced them.

In the same period came Gotch’s observation that the potential wave in a nerve had an equal duration whether it was set up by a strong or a weak stimulus. As it seemed unlikely that a feeble and an intense disturbance would last for the same time, Gotch suggested that in each nerve fibre the disturbance was always of the same intensity, and that a strong stimulus set up a larger potential wave merely because it brought more fibres into activity. This agreed with the fact that the rate of conduction and the length of the refractory period were also uninfluenced by the strength of the stimulus. It seemed, therefore, that each pulse of activity in a nerve fibre must be of constant intensity, involving the entire resources of the fibre whatever the strength of the stimulus which set it in motion. The fibre was a unit giving always its maximal response, behaving like the heart muscle in this respect as well as in that of its refractory state. Conclusive proof was lacking, but Gotch’s work made it likely that the same all-or-nothing behaviour might be found in skeletal muscle fibres. Keith Lucas recorded the contraction of a band of muscle containing only a few fibres and found that with an increasing stimulus the contraction increased in sudden steps. The number of steps was never greater than the number of fibres in the preparation. It was clear, then, that skeletal muscle fibres followed the all-or-nothing rule.

I have mentioned this work of Keith Lucas (confirmed later by Pratt) because it was the first direct evidence of the ungraded character of the wave of activity in excitable tissues other than the heart. It was also the first successful attempt to record the behaviour of the units in muscle and nerve instead of inferring the behaviour of the units from that of the whole aggregate. A few years later I had the great good fortune to work with him, to appreciate his technical skill and his penetrating thought. I cannot let this occasion pass by without recording how much I owe to his inspiration. In my own work I have tried to follow the lines which Keith Lucas would have developed if he had lived, and I am happy to think that in honouring me with the Nobel Prize you have honoured the master as well as the pupil.

After Keith Lucas’s work on muscle, attempts were made to secure more evidence as to the all-or-nothing reaction of the nerve fibre. Verworn and his school showed that the strength of the stimulus made no difference to the ability of the impulse to pass through a narcotized area, and Lucas and I made use of the same method. Its value seemed to lie in its offering a means of measuring the impulse in terms of its ability to travel, but Kato has since pointed out the fallacies which arose from supposing that the impulse became progressively smaller as it passed through the affected region.

More direct evidence was lacking, but at the end of this period we had good reason to believe that the nerve impulse was a brief wave of activity depending in no way on the intensity of the stimulus which set it up. We did not know for certain that the nervous signalling in the intact animal was carried out by means of such impulses, but it seemed highly probable – so much that we could elaborate hypotheses to explain the working of the central nervous system in terms of the interference and reinforcement of trains of impulses.

It was at this point that the need arose for a more sensitive electrical technique. When a nerve trunk is stimulated by an electric shock every fibre is thrown into action simultaneously and the total potential change in the whole nerve is large enough to be recorded directly. But in more normal circumstances the nerve fibres work as independent conducting units, and simultaneous activity in many fibres is a rare event. Potential changes could be detected when there was reason to believe that signals were passing, but to analyse these changes was a far more difficult problem. Granting that they were caused by the passage of impulses of the familiar type, there was little or nothing to show how the impulses were spaced. Records of the electric changes in contracting muscle seemed to one school to imply a very high frequency of discharge in each nerve fibre. Others believed that the frequency was lower, but neither side could find convincing evidence. To show clearly what kind of signals passed from the sense organs to the brain and from the brain to the muscles it would have been necessary to record the electrical events in the individual nerve fibres. The potentials to be dealt with are of the order of a few microvolts lasting for a few thousandths of a second. They were quite beyond the reach of the instruments available at the time, and other lines of evidence had to be followed. These were indirect and, in fact, most of them led nowhere.

The revolution in technique has come about not from any increase in the sensitivity of galvanometers and electrometers but from the use of the thermionic valve to amplify potential changes. The recording instruments used nowadays are actually far less sensitive than their predecessors. Since the energy available is almost unlimited, any system can be chosen which will react rapidly enough and the limiting factor has become not the period of the instrument but that of the amplifying circuits. There is a lower limit to the sensitivity of a valve, but fortunately a change as small as one or two microvolts is within the range of useful amplification. Many workers have contributed to the introduction of this technique into physiology, notably Forbes of Harvard, Gasser of St. Louis, who was the first to use very high amplification, and Matthews of Cambridge who devised the convenient moving-iron oscillograph which is now in common use; to all these my own work is deeply indebted.

Seven years ago it became clear to me that a combination of the capillary electrometer with an amplifier would permit the recording of far smaller potential changes than had been dealt with previously, and might enable us to work on the units of the nerve trunk instead of on the aggregate. A preliminary survey confirmed this, for it showed that the normal activity of sensory and motor fibres was always accompanied by potential changes of the familiar type. The problem was then to limit the activity to only one or two nerve fibres. In this I was happy to have the cooperation of Dr. Zotterman of the Caroline Institute. We found that the Sterno-cutaneous muscle of the frog could be divided progressively until it contained only one sense organ; this could be stimulated by stretching the muscle, and we could record the succession of impulses which passed up the single sensory nerve fibre.

A variety of methods now exists for studying in this way the activity of individual sensory and motor nerve fibres. Many records have been made of the signals which they transmit in the normal working of the organism and in every case the signals are found to be extremely simple. They consist of nerve impulses repeated more or less rapidly, impulses which differ in no way from those already studied by the classical methods of electro-physiology. This may have seemed no more than a proof of what was already obvious, but our records showed another point which was more illuminating. To illustrate this we may take the discharge produced by stretching a muscle spindle. A record of the potential changes in the nerve shows a succession of brief diphasic waves, each due to the passage of a single impulse along the nerve fibre. The waves are of constant size and duration, but they begin at a frequency of about 10 a second, and as the extension increases, their frequency rises to 50 a second or more. The frequency depends on the extent and on the rapidity of the stretch; it depends, that is to say, on the intensity of excitation in the sense organ, and in this way the impulse message can signal far more than the mere fact that excitation has occurred.

In all the sense organs which give a prolonged discharge under constant stimulation the message in the nerve fibre is composed of a rhythmic series of impulses of varying frequency. Hartline, for instance, has shown that the discharge from one of the light-sensitive receptor organs in the eye of Limulus is a fairly close copy of that from a frog’s muscle spindle. With some kinds of sense organ there is a rapid adaptation to the stimulus, and the nervous discharge is too brief to show a definite rhythm, though it consists as before of repeated impulses of unvarying size.

The nerve fibre is clearly a signalling mechanism of limited scope. It can only transmit a succession of brief explosive waves, and the message can only be varied by changes in the frequency and in the total number of these waves. Moreover, the frequency depends on the rate of development of the stimulus, as well as on its intensity; also the briefer the discharge the less opportunity will there be for signalling by change of frequency. But this limitation is really a small matter, for in the body the nervous units do not act in isolation as they do in our experiments. A sensory stimulus will usually affect a number of receptor organs, and its result will depend on the composite message in many nerve fibres. A good example of this is to be found in the discharge which passes up the nerve from the carotid sinus at each heart beat. Bronk and Stella have shown that as the blood pressure rises, the impulses in each nerve fibre increase in frequency and more and more fibres come into action. Since rapid potential changes can be made audible as sound waves, a gramophone record will illustrate this, and you will be able to hear the two kinds of gradation, the changes in frequency in each unit and in the number of units in action.

The sense organs which are most easily investigated in this way are those which react to mechanical deformation-tactile endings, muscle spindles and the like. They are supplied by the larger nerve fibres in which the potential change can be readily detected. But there are many sensory nerve fibres which are exceedingly small. The recent work of Erlanger and Gasser and of Ranson has made it highly probable that some of these fibres are concerned with pain, and this alone makes it essential to learn more about their normal activities. For such problems our present methods are still scarcely adequate, for in the smallest fibres the potential changes are probably too small to appear above the random fluctuations due to the operation of the thermionic valve. But we may hope that this failure will be remedied before long.

There is another field of sensory physiology which seemed at first to offer special difficulties but is now more promising. This is the field of the special sense organs. With Mrs. Matthews I investigated the activity of the vertebrate optic nerve, but although the usual impulse messages could-be recorded they gave very little information about the working of the receptor organs in the retina. The reason is that the retina is a complex nervous structure. The messages in the optic nerve fibres have been elaborated by the interaction of many nerve cells, even though the stimulus is restricted so as to fall on a very small number of rods and cones. We learnt something of the processes which take place in groups of nerve cells with synaptic connections, but little about the action of light as a sensory stimulus. Fortunately this difficulty has been overcome by Hartline, who finds that in the eye of Limulus there is no evidence of such interaction and no reason to expect it on grounds of structure. And since his work is showing what takes place in the receptors themselves, the complexities of the vertebrate retina become less formidable.

The messages in the vertebrate optic nerve have come not from receptor organs but from nerve cells. They are comparable, therefore,- with the messages which are sent from the motor nerve cells to the muscles. The grading and coordination of muscular activity is a subject which has been so greatly illuminated by my friend Sir Charles Sherrington that I mention my own work as a very small supplement to his. It has dealt as before with the signals which are sent by the individual nerve fibres, and its results emphasize the close correspondence between the sensory and motor activities of the nervous system. The messages which pass down the motor fibres to the muscles have, of course, the same limitations as the sensory messages, and again we find that the effect is graded by changes in the frequency of the impulse discharge and in ‘the number of units in action. In a contraction of gradually increasing force the nerve fibres transmit a succession of impulses beginning at a very low frequency (5 to 10 a second) and rising to 40 or 50 a second at the height of the contraction; and as the frequency rises in one nerve fibre, another will start at a low frequency and then more and more, until it becomes impossible to distinguish the individual rhythms. The force of contraction varies with the impulse frequency, because in a muscle fibre each impulse produces a mechanical effect of relatively long duration and the successive effects of a series of impulses can be summed to give a greater contraction. Thus the result of the intermittent message in each nerve fibre is a much less intermittent contraction in a group of muscle fibres, and in the whole muscle there are so many of these fibre groups working independently that the contraction rises and subsides smoothly.

On the whole it appears that the frequency of the impulses varies over a more restricted range in the motor than in the sensory discharge, but the two are so closely alike that the mechanism of the sense organ and of the motor nerve cell must have much in common. They have, of course, the common factor of a nerve fibre which can only respond in one way, but the likeness goes beyond this. Also the particular frequencies which commonly occur are lower than they would be if determined solely by the characteristics of the nerve fibre. In quiet breathing, for instance, at each expansion of the lungs the sense organs of the vagus send up a train of impulses rising to a frequency of about 20 a second at the height of inspiration, and simultaneously the movement of expansion is being produced by trains of motor impulses rising to much the same frequency and almost indistinguishable from the discharge in the sensory fibres. In fact the motor nerve cells seem to be acting just like a collection of sense organs responding to a rhythmic stretch.

Resemblances of this kind show that there is an underlying unity of response in the various parts of the neurone in spite of their differentiation into axon, dendrites or terminal arborizations. They show, too, that a knowledge of the mechanism of the sensory end organ might lead us very far in our search for the mechanisms of the central nervous system. Here we must enter a more speculative region, but there are certain pointers to guide us. In the nerve fibre, for instance, a rhythmic discharge of impulses may arise from an injured region. Electrically such a region behaves as though it were permanently instead of momentarily active. It is at a negative potential to the rest of the fibre owing to the destruction of the polarized surface membrane, and we have fair grounds for supposing that the rhythmic discharge is a consequence of this depolarization. A closer parallel with the sense organ is afforded by a muscle fibre bathed in a solution of NaCl instead of its usual Ringer’s fluid. Sooner or later such a fibre becomes spontaneously active, the activity consisting of a serial discharge of impulses from some point. At an earlier stage, however, the activity can be started, as with a sense organ, by mechanical deformation, and it ceases when the deformation is over. Thus a muscle fibre may discharge impulses in response to stretch or touch almost as though it had been transformed into a muscle spindle or a touch receptor, though naturally it is a far less perfect instrument for translating mechanical stress into an impulse message. Here again there is reason to suppose that discharge of impulses is due to a breakdown in the polarized surface, a breakdown which is repaired as soon as the mechanical stress is removed.

Analogies of this kind suggest that sense organs and nerve cells send out impulses because some part of their surface has become depolarized. There are certain difficulties to be faced before this can be treated as more than a crude working hypothesis, but it is one which has important consequences. If the regions from which the discharge originates remain partly or wholly depolarized as long as they are excited, it should be possible to detect potential changes of relatively long duration in sense organs and in the motor nerve centres. Such changes are well known to occur in the eye, and they have been found in the vertebrate brain stem and in the nerve ganglia of insects. Unfortunately the structures in which they occur are so complex that it is difficult to be sure of their interpretation, but at least they suggest the possibility of obtaining direct records of the activities of the grey matter. To extract much information from such records is likely to be a far harder task than it has been in the case of peripheral nerve. In the latter our chief concern is to find out what is happening in the units, and this turns out to be a fairly simple series of events. Within the central nervous system the events in each unit are not so important. We are more concerned with the inter-actions of large numbers, and our problem is to find the way in which such interactions can take place*.

*The lecture was illustrated by lantern slides and gramophone records.

Edgar Adrian – Banquet speech

Edgar Adrian’s speech at the Nobel Banquet in Stockholm, December 10, 1932

Your Royal Highness, your Excellencies, my Lords, Ladies and Gentlemen

In my College at Cambridge – Trinity College – all of us know of Stockholm as the beautiful capital of a country which has a great history and is now in the forefront of modern civilisation. There are some of us who try very hard to copy your artistic enterprise and to decorate our houses in the Swedish manner, and our learned societies can be divided into two classes – those who have attended an international congress at Stockholm and those who have not, and do not know, therefore, how pleasant such events can be.

Trinity is a very large College, but however large we were we should still be immensely proud of the fact that in the past no less than eight of us have had a special reason to praise your hospitality. Eight of the Fellows of Trinity have had reason to look back on their visit here as an outstanding event in their lives, for eight have made the winter journey to attend the Nobel celebrations and have gone back far the richer – richer in pocket of course – but richer too in the tremendous encouragement which comes from such an award.

Eight Nobel prizemen is a large number, and however great your admiration for science you may wonder whether one cannot have too much of a good thing! You may fancy that a College in which eight Nobel prizemen live together would not be a very comfortable place for anybody else. But I have really exaggerated our good fortune for in fact only two of our prizemen live in the College and only four in Cambridge.

And now I make the ninth to come on the same errand and even after today’s impressive ceremony I still find it very hard to believe that so high an honour should have fallen to me. But at least I have had one special advantage among scientific workers. For five years I lived in Cambridge in the rooms which belonged, nearly 300 years ago, to the great astronomer and physicist, Sir Isaac Newton. He had a living room and a study looking out on to the Great Court of Trinity and a small and very cold bedroom.

Newton was our greatest English scientist and I do not think that anyone living in such surroundings could fail to be infected with the spirit of scientific enquiry. Perhaps in these days we do not regard the laws of gravitation with the same reverence as did our fathers, but we have, unfortunately, more reason to be impressed by his ability in another field – for much of his life was spent in London in the Government Service reorganising the coinage of England in a way which did much to restore prosperity at a time when it was badly needed.

But although I have lived in such inspiring surroundings, in another way I suffer from my upbringing. As you know from Mr Galsworthy’s novels, in my country we are not skilled at expressing our emotions and we are not encouraged to do so, whatever we may feel. And so now I feel very great happiness and very deep gratitude to the memory of Alfred Nobel, to the Committee and to you all, but all that I can find to say is “Thank you very much indeed!”

Edgar Adrian – Photo gallery

Portrait of Edgar Adrian. Photo taken ca 1929.

Source: U.S National Library of Medicine, Images from the History of Medicine Collection Photographer unknown Kindly provided by National Library of Medicine

Edgar Adrian in the laboratory. Photo taken ca 1920.

Source: U.S National Library of Medicine, Images from the History of Medicine Collection Photographer unknown Kindly provided by National Library of Medicine

Edgar Adrian – Nominations

Sir Charles Sherrington – Nominations

Sir Charles Sherrington – Other resources

Links to other sites

On Sir Charles Sherrington from Magdalen College

Sir Charles Sherrington – Nobel Lecture

Nobel Lecture, December 12, 1932

Inhibition as a Coordinative Factor

That a muscle on irritation of its nerve contracts had already long been familiar to physiology when the 19th century found a nerve which when irritated prevented its muscle from contracting. This observation seemed for a time too strange to be believed. Its truth did not gain acceptance for ten years; but at last in 1848 the Webers accepted the fact at its face value and proclaimed the vagus nerve to be inhibitory of the heart muscle. Two hundred years earlier Descartes, in writing the De Homine, had assumed that muscle was supplied with nerves which caused muscular relaxation. An analogous suggestion was put forward by Charles Bell in 1819. The inhibition suggested was in each case “peripheral”. “Peripheral” inhibition, despite its inherent probability, was however to prove void of the fact for skeletal muscle. As just said, it did in fact prove true for the heart; it was found somewhat later to hold good likewise for visceral muscle; and, somewhat later still, was found for the constrictor muscles of the blood vessels. Peripheral inhibition became thus by the sixties and seventies of the 19th century a recognized fact, save for the one important exception of the skeletal muscles.

The first experimental indication of inhibition as a process working within the nervous system itself appeared in 1863. Setschenov then noted in the frog that the local reflexes of the limb are depressed by stimulation of the exposed midbrain. Later (1881), somewhat similarly, stimulation of the foot (dog) was found to restrain movements of the foot excited from the brain (Bubnoff and Heidenhain). Matters had, broadly put, reached and remained at that stage, when in the century’s last decade experimental examination of mammalian reflexes detected (1892) examples of inhibition of surprising potency and machine-like regularity, readily obtainable from the mammalian spinal cord in its action on the extensors of the hind limb; the inhibitory relaxation of the extension was linked with concomitant reflex contraction of their antagonistic muscles, the flexors. This “reciprocal innervation” was quickly found to be of wide occurrence in reflex actions operating the skeletal musculature. Its openness to examination in preparations with “tonic” background (decerebrate rigidity) made it a welcome and immediate opportunity for the more precise study of inhibition as a central nervous process.

The seat of this inhibition was soon shown to be central, e.g. for spinal reflexes, in the grey matter of the spinal cord. The resulting relaxation of the muscle was found to be both in range and nicety as amenable to grading as is reflex contraction itself. In other words the inhibitory process was found capable of no less delicate quantitative adjustment than is the excitatory process. In “reciprocal innervation” the two effects, excitation and inhibition, ran broadly pari passu; a weak stimulus evoked weak inhibitory relaxation along with weak excitatory contraction in the antagonist muscle; a strong stimulus evoked greater and quicker relaxation accompanying greater and speedier contraction of the antagonist. No evidence was forthcoming that the centripetal nervous impulses which on their central arrival give rise to inhibition differ in nature from nerve impulses giving rise centrally to “excitation”, or indeed differ from the impulses travelling nerve fibres elsewhere. An “inhibitory” afferent nerve emerged simply as an afferent nerve whose impulses at certain central loci cause, directly or indirectly, inhibition, while at other central loci the same nerve, probably even the same nerve fibre can produce excitation. There was no satisfactory evidence that an afferent nerve fibre whose end-effect is inhibitory ever for its end-effect at that same locus evokes excitation or indeed any other effect than inhibition. That is to say its inhibitory influence never changes to an excitatory influence, or vice versa. Fixity of central effect, inhibitory or excitatory respectively, has to be accepted for the individual afferent fibre acting in a specified direction, i.e. on a specified individual effector unit. That does not of course exclude the contingency that an inhibitory influence on a given unit may under some circumstances be unable to produce effective inhibition there owing to its being too weak to overcome concurrent excitation.

I will not dwell upon the features of reciprocal innervation; they are well known. I would only remark that owing to the wide occurrence of reciprocal innervation it was not unnatural to suppose at first that the entire scope of reflex inhibition lay within the ambit of the taxis of antagonistic muscles and antagonistic movements. Further study of central nervous action, however, finds central inhibition too extensive and ubiquitous to make it likely that it is confined solely to the taxis of antagonistic muscles.

In instance let us take a reflex especially facile and regular to type, the well-known spinal flexion-reflex of the leg, evoked by stimulation of any afferent.280 1932 nerve of the leg itself Its experimental stimulus may be reduced to a single induction shock evoking a single volley of centripetal impulses in the bared afferent nerve. The reflex effect, observed in an isolated flexor muscle, e.g. of the ankle, is apart from exceptional circumstances, a single contraction wave indicating discharge of a single volley of motor impulses from the spinal centre. This “twitch-reflex”, recorded isometrically by the myograph, exhibits a tension proportional to the number of motor units engaged, in other words to the size of the single centrifugal impulse volley. The contraction of each motor unit is on the all-or-nothing principle. The maximal contraction-tension for the reflex twitch will be reached only when all of the motor units composing the muscle are activated. The contraction-tension developed by the reflex being proportional to the number of motor units engaged, an average contraction-tension value for the individual motor unit can be found. The contraction developed by the reflex twitch is less the weaker the induction shock exciting the afferent nerve, in other words the fewer the afferent fibres excited, in short, the smaller the size of the centripetal impulse volley. With a given single-shock stimulus the tension developed by the reflex twitch remains closely constant when sampled at not too frequent intervals. In the case of the spinal flexion-reflex therefore, though with many other reflexes it is not so, a standard reflex twitch of desired size (tension) can be obtained at repeated intervals.

The only index available at present for inhibition is its effect on excitation; thus, a standard twitch-reflex, representing a standard-sized volley of centrifugal discharge, can serve as a quantitative test for reflex inhibition. It serves for this with less ambiguity than does a reflex tetanus. In the tetanus the tension developed will depend within limits on the repetitive-frequency of the contraction waves forming the tetanus. Maximal tetanic contraction is reached only when the frequency reaches a rate which, in many reflex tetani, some of the units do not attain. In reflexes the rate of tetanic discharge can differ from unit to unit in one and the same muscle at one and the same time. The rate will differ too at different stages of the same reflex and according as the reflex is weak or strong. Reflex inhibition acting against a reflex titanic contraction may diminish the contraction in one or other or all of several different ways. In some units it may suppress the motor discharge altogether, in some it may merely slow the motor discharge thus lessening the wave frequency of the contraction and so the tension. The same aggregate diminution of tension may thus be brought about variously and by various combinations of ways, a result too equivocal for analysis. The same gross result might accrue (a) from total suppression of activity in some units or (b) from mere slackening of discharge in a larger number of units. These difficulties of interpretation are avoided by using as gauge for inhibition a standard reflex twitch. The deficit of contraction-tension then observed shows unequivocally the number of motor units inhibited out of the total activated for the standard. Since the direct maximal motor twitch compared with the standard reflex twitch can reveal the proportion of the whole muscle which the standard reflex twitch activates, we can find further what proportion of the whole muscle is reflexly inhibited. Of course subliminal excitation and subliminal inhibition are not revealed by the test and require other means for detection.

A stable excitatory twitch-reflex as standard allows us to proceed further in our quantitative examination of inhibition. We then find that inhibition can be admixt in our simple-seeming flexion-reflex itself, and indeed usually is so. To detect it we have simply to add to the earlier excitation of the reflex a following one at not too long interval; we then find the response to the second stimulus-volley partly cut down by an inhibition latent in the first.

This is usually evident with intervals between 300-1,200 sigma. The very shortest interval at which the inhibitory effect occurs is difficult to determine, for the reason that the excitatory effect has a subliminal fringe and the second stimulus repeats the subliminal effect of the first, and the two subliminal effects can sum to liminal. The second response is therefore enlarged by summation of subliminal fringe in some of the responsive motor units. This activation by the second stimulus of some motor units facilitated for it by the first though not activated by the first alone tends of course to obscure the inhibitory inactivation; the shrinkage due to the latter is offset by the increment due to the former. The inhibition is traceable only by the net diminution of the second reflex twitch. How quickly the inhibitory element in the stimulus develops centrally is not fully ascertainable, because the sooner the second reflex follows on the first the more the facilitation from it that it gets. This increment will conceal at least in part the decrement due to inhibition. Similarly the beginning of the inhibition may be concealed from observation by concomitant excitatory facilitation. This uncertainty does not attach to the longer intervals between the two stimuli because the central inhibitory process considerably outlasts the central excitatory facilitation.

The reflex therefore, which at first sight seems a purely excitatory reaction, proves on closer examination to be in fact a commingled excitation and inhibition. Usually clearly demonstrable in the simple spinal condition of the reflex, this complexity of character is yet more evident in the decerebrate condition.

We may hesitate to generalize from this example, because a stimulus applied to a bared afferent nerve is of course “artificial” in as much as it is applied to an anatomical collection of nerve fibres not homogeneous in function; and, we may suppose, not usually excited together. If cutaneous, its fibres will belong to such different species of sense as “touch” and “pain” which often provoke movements of opposite direction and are therefore in their effect on a given muscle opposed in effect. That a strong stimulus to such an afferent nerve, exciting most or all of its fibres, should in regard to a given muscle develop inhibition and excitation concurrently is not surprising.

With weak stimuli the case is somewhat different. Such stimuli excite only a few of the constituent fibres of the afferent nerve, and those of similar calibre, presumably an indication of some functional likeness. Nevertheless, as shown above, the reflex result even then exhibits admixed excitatory and inhibitory influence on one and the same given muscle. And this admixture of excitation and inhibition persists when the stimulus is reduced in strength still further so as to be merely liminal. It still is so when the afferent nerve chosen is homogeneous in the sense that it is a purely muscular afferent, e.g. the afferent from one head of the gastrocnemius muscle. But we must remember that the afferent nerve from an extensor muscle has been shown to contain fibres which exert opposite reflex influences upon their own muscle, some exciting and some inhibiting that muscle’s contraction. This brings with it the question whether admixture of exciting and inhibiting influence in the reflex effect obtains when instead of stimulation of a bared nerve some more “natural” stimulation is employed.

For this the reflex evoked by passive flexion of knee in the decerebrate preparation has been taken. The single-joint extensor (vasto-crureus) of each knee is isolated; and nothing but that muscle pair thus retained is still innervated in the whole of the two limbs. The preparation thus obtained is a tonic preparation; one of the two muscles is then stretched by passively flexing a knee. This passive flexion excites in the extensor muscle which it stretches a reflex relaxation, i.e. the lengthening reaction; this relaxation at one knee is accompanied in the opposite fellow vasto-crureus by a reflex contraction enhancing the existing “tonic” contraction. The reflex contraction thus provoked is characteristically deliberate and smooth in performance and passes without overshoot into a maintained extension posture. Let however the manoeuvre be then repeated with the one difference of condition, that the muscle contralateral to that which is passively stretched has been deafferented. In the deafferented muscle contraction is still obtained, and more easily than before, but the deafferented condition of the muscle alters the course of its contraction in two respects. The course is no longer deliberate. The contraction is an abrupt rush, with overshoot of the succeeding postural contraction, and this latter is hardly maintained at all. The severance of the afferent nerve has removed a reflex self-restraint from the contracting muscle. Normally the proprioceptives of the contracting muscle put a brake on the speed of the contracting muscle (autogenous inhibition). The explosive rush and momentum of these deafferented extensor reflexes recall the ataxy of tabes. They recall also the abruptness and overshooting of the “willed” movements of a deafferented limb. In both cases a normal self-braking has been lost along with the deprivation of the muscle of its own proprioceptive afferents. These latter mediate both a self-braking and a self-exciting (autogenous excitation) reflex action of the muscle. Thus here again there is admixture of reflex inhibition and excitation, and in this case the admixture obtains in response to a “natural” stimulation. Here therefore the admixture of central inhibition with central excitation is a normal feature of a natural reflex.

This makes it clear that for the study of normal nervous coordinations we require to know how central inhibition and excitation interact. As said above, the centripetal impulses which evoke inhibition do not differ in nature from those which evoke excitation. Inhibition like excitation can be induced in a “resting” centre. The only test we have for the inhibition is excitation. Existence of an excited state is not a prerequisite for the production of inhibition; inhibition can exist apart from excitation no less than, when called forth against an excitation already in progress, it can suppress or moderate it. The centripetal volley which excites a “centre” finds, if preceded by an inhibitory volley, the centre so treated is already irresponsive or partly so.

A first question is, are there degrees of “central inhibitory state”; and are they, like central excitatory state, capable of summation. This can be examined in several ways. Thus: against the central inhibition caused by a given single volley of inhibitory impulses a standard single volley of excitatory impulses can be launched at an appropriate interval. The relatively long duration of the central inhibitory state allows a second inhibitory volley to be interpolated between the original inhibitory volley and the standard excitatory volley. The standard excitation is found to be then diminished (as shown by the twitch-contraction which it evokes) more than it is if subjected to either one inhibitory volley only. This holds even when the second inhibitory volley, launched from the same cathode as the first, is arranged to be clearly smaller than the first. Since the distribution of the effect of the smaller impulse volley (launched from the same cathode as the larger) among the motoneurones of the centre must lie completely included within that of the first, the added inhibition due to the second volley indicates that the combined influence of the two volleys prevents activation of some motoneurones which neither inhibitory volley acting alone was able to prevent from being activated. Evidently therefore central inhibition sums; consequently it is capable of subliminal existence. Also, successive subliminal degrees of inhibition can by temporal overlap sum to supraliminal degree. In these ways central inhibition presents analogy with its converse “central excitations”; both exhibit various degrees of intensity in respect to the individual motoneurone.

Summation of inhibition is well exhibited when a given twitch-reflex is evoked at various times during and after a tetanic inhibition. The cutting down of the reflex twitch is progressively greater, as within limits, the inhibitory tetanus proceeds. After cessation of the tetanus the inhibitory state, similarly tested, passes off gradually, more quickly at first than later.

The relatively long persistence of the central inhibitory state induced by a single centripetal impulse volley allows examination of the effect on it of two successive excitation volleys as compared with one of the two alone. An excitatory volley is interpolated between the inhibitory volley and a subsequent standard excitatory volley. The interpolated excitatory volley is found to lessen the inhibitory effect upon the final excitatory volley. The interpolated excitation volley neutralizes some of the inhibition which otherwise would have counteracted the final test excitation. Just as central inhibitory state (c.i.s.) counteracts central excitatory state (c.e.s.) so c.e.s. neutralizes c.i.s. The mutual inactivation is quantitative. There occurs at the individual neurone an algebraic summation of the values of the two opposed influences.

It is still early to venture any definite view of the intimate nature of “central inhibition”. It is commonly held that nerve excitation consists essentially in the local depolarization of a polarized membrane on the surface of the neurone. As to “central excitation”, it is difficult to suppose such depolarization of the cell surface can be graded any more than can that of the fibre. But its antecedent step (facilitation) might be graded, e.g. subliminal. Local depolarization having occurred the difference of potential thus arisen gives a current which disrupts the adjacent polarization membrane, and so the “excitation>. travels. As to inhibition the suggestion is made that it consists in the temporary stabilization of the surface membrane which excitation would break down. As tested against a standard excitation the inhibitory stabilization is found to present various degrees of stability. The inhibitory stabilization of the membrane might be pictured as a heightening of the “resting” polarization, somewhat on the lines of an electrotonus. Unlike the excitation-depolarization it would not travel; and, in fact, the inhibitory state does not travel.

The quantitative character of the interaction between opposed inhibition and excitation is experimentally demonstrable. Thus: a given inhibitory tetanus exerted on a certain set of motoneurones fails to prevent their excitation in response to strong stimulation of a given afferent nerve; but when the stimulation of the excitatory afferent is weaker the given standard inhibitory tetanus does prevent the response of the motor neurones to the excitatory stimulation. With the weaker stimulation of the afferent nerve there are fewer of its fibres acting, and therefore fewer converge for central effect on some of the units. On these the standard c.i.s. has therefore less c.e.s. to counteract.

Many features characteristic of reflex myographic records of various type become interpretable in light of the stimulus volley from a single afferent nerve trunk, even small, evoking an admixture of inhibition and excitation, with consequent central conflict and interaction between them. Features which find facile explanation in this way are the following. (A) The flexion-reflex (spinal) commonly has a d’emblée opening; that is, a steep initial contraction passes abruptly into a plateau, giving an approximately rectangular beginning to the myogram. Here the initial reflex excitation is closely followed by an ensuing reflex inhibition commingled with and partially counter-acting the concurrent excitation. (B) Allied to this and of analogous explanation is the so-called “fountain”- form of flexion-reflex. After the first uprush of contraction a component of reflex inhibition grows relatively more potent and the contraction-tension drops low before continuing-level. Between these extreme forms there are intermediates. The key to the production of them all is admixture of central excitation with central inhibition; the excitation is prepotent earlier, and later suffers from encroaching inhibition.

(C) Again, the typical opening of the crossed extensor reflex (decerebrate) “recruits”. A variably long latent period precedes a contraction which climbs slowly, taking perhaps seconds to reach its plateau. Here, struggling with excitation, inhibition has the upper hand at first. The action currents of the muscle marking the serial stimuli to the afferent nerve are not choked by secondary waves of after-discharge. The concurrent inhibition cuts them out. The inhibition is traceable partly to the proprioceptive reflex mechanism attached to the contracting muscle itself; the progress of the reflex contraction is partly freed from inhibition by deafferenting the muscle, but still not wholly freed. A residuum of inhibition in the reflex is traceable to the crossed afferent nerve employed. This again illustrates the ubiquitous commingling of inhibition and excitation in the spinal and decerebrate reflexes evoked by direct stimulation of afferent nerves.

An instance of combination of excitation and inhibition for coordinative effect is the rhythmic reflex of stepping. In the “spinal” cat and dog there occurs “stepping” of the hind limbs; it starts when the “spinal” hind limbs, lifted from the ground, hang freely, the animal being supported vertically from the shoulders. The extensor phase in one limb occurs with the flexor phase in the other. This “stepping” can also be evoked by a stigmatic electrode carrying a mild tetanic current to a point in the cross-face of the cut spinal-cord. The “stepping” then opens with Aexion in the ipsilateral hind limb accompanied by extension in the contralateral. To reproduce this stepping movement by appropriately timed repetitions of tetanization of, for instance, a flexion producing afferent of one limb or an extension-producing afferent of the other never succeeds even remotely in exciting the rhythmic stepping. In the true rhythmic movement itself, which has been examined particularly by Graham Brown, the contraction in each phase develops smoothly to a climax and then as smoothly declines, waxing and waning much as does the activity of the diaphragm in normal inspiration. But although this rhythmically intermittent tetanus affecting alternately the flexors and extensors of the limb and giving the reflex step cannot be copied reflexly by employing excitation alone, it can be easily and faithfully reproduced and with perfect alternation of phase and with its characteristic asymmetrical bilaterality, by employing a stimulation in which reflex excitation and reflex inhibition are admixt in approximately balanced intensity. The result is then a rhythmic sea-saw about a neutral point. The effect on the individual motor unit appears then to run its course thus: if we start to trace the cycle with the moment when c.e. and c.i. are so equal as to cancel out, the state of the motoneurone is a zero state, for which the term “rest”, although often applied to it, is perhaps better avoided. With supervention of preponderance of c.e. over c.i. the motor neurone’s discharge commences and under progressive increase of that preponderance the frequency of discharge increases in the individual motor neurone, and more motor neurones are “recruited” for action until in due course the preponderance of c.e. begins to fail and c.i. in its turn asserts itself more. The recruitment and frequency of discharge begin to wane, and then reach their lowest, and may cease, and an interval of zero state or quiescense may ensue. The quiescence may be inhibitory or merely lack of excitation. Which of these it were could be directly determined only by testing the threshold of excitation. However brought about, it is synchronous with the excitation-phase in the antagonistic muscle and with the excitation-phase in the symmetrical fellow muscles of the opposite limb. Since reciprocal innervation has been observed to obtain between these muscles, the phase of lapse of excitation is probably one of filer active inhibition. The rhythm induced by stimulation of the “stepping”-point in the cut face of the lateral column of the cord would seem to act therefore by evoking concurrently excitation and inhibition, and so playing them off one against the other as to induce alternate dominance of each. Intensifying the mild current applied to the point quickens the tempo of the rhythm, i.e. of the alternation.

Another class of events revealing inhibition as a factor wide and decisive in the working of the central nervous system is presented by the “release” phenomenon of Hughlings Jackson. The depression of activity called “shock” supervenes on injury of a distant but related part; conversely there supervenes often an over-action due likewise to injury or destruction of some distant but related part. “Shock” is traceable to loss of excitatory influence, which, though perhaps commonly subliminal in itself, lowers the threshold for other excitation. The over-action conversely is traceable to loss of inhibitory influence, perhaps subliminal in itself and yet helping concurrent influences of like direction to maintain a normal restraint, the normal height of threshold against excitation. Where the relation between one group of muscles and another, e.g. between flexors and extensors, is reciprocal, the effect of removal (by trauma or disease) of some influence exerted by another part of the nervous system is commonly two-fold in direction. There is “shock”, i.e. depression of excitability in one field of the double mechanism and “release”, i.e. exaltation of excitability, in another. Thus spinal transection, cutting off the hind-limb spinal reflexes from prespinal centers inflicts “shocks” on the extensor half-centre and produces “release” of the flexor half-centre. In this case the direction both of the “shock” and of the “release” runs aborally ; but it can run the other way, as in the influence that the hind-limb centres have on the fore-limb. Which way it runs, of course, depends simply on the relative anatomical situation of the influencing and the influenced centres.

The role of inhibition in the working of the central nervous system has proved to be more and more extensive and more and more fundamental as experiment has advanced in examining it. Reflex inhibition can no longer be regarded merely as a factor specially developed for dealing with the antagonism of opponent muscles acting at various hinge-joints. Its role as a coordinative factor comprises that, and goes beyond that. In the working of the central nervous machinery inhibition seems as ubiquitous and as frequent as is excitation itself. The whole quantitative grading of the operations of the spinal cord and brain appears to rest upon mutual interaction between the two central processes “excitation” and “inhibition”, the one no less important than the other. For example, no operation can be more important as a basis of coordination for a motor act than adjustment of the quantity of contraction, e.g. of the number of motor units employed and the intensity of their individual tetanic activity. This now appears as the outcome of nice co-adjustment of excitation and inhibition upon each of all the individual units which cooperate in the act.

In reflexes, even under simple spinal or decerebrate conditions, interplay between excitation and inhibition is commonly induced even by the simplest stimulus. It need not surprise us therefore that variability of reflex result is met by the experimenter. Indeed, that it troubles him by being partly beyond his control, need not surprise him in view of the multiplicity and complicity of the sources of the inhibition and of the excitation. This variability seems underestimated by those who regard reflex action as too rigid to provide a prototype for cerebral behaviour. It is in virtue of their containing inhibition and excitation admixt that, in accord with central conditions prevailing for the time being, a limb-reflex provoked by a given stimulus in the decerebrate preparation can on one occasion be opposite in direction to what it is on another, e.g. extension instead of Aexion (“reversal”) Excitation and inhibition are both present from the very stimulus out-set and are pitted against one another. The central circumstances may favour one at one time, the other at another. Again, if the quantity of contraction needed normally for a given act be reached by algebraic summation of central excitation and inhibition, it can obviously be attained by variously compounded quantities of those two. Hence when disease or injury has caused a deficit of excitation, a readjustment of concurrent inhibition offers a means of arriving once more at the normal quantity required. The admixture of inhibition and excitation as a mechanism for coordination thus provides a means of understanding the remarkable “compensations” which restore in course of time, and even quickly, the muscular competence for execution of an act which has been damaged by central nervous lesions. More than one way for doing the same thing is provided by the natural constitution of the nervous system. This luxury of means of compassing a given combination seems to offer the means of restitution of an act after its impairment or loss in one of its several forms.

The Nobel Foundation's copyright has expired.Sir Charles Sherrington – Banquet speech

Sir Charles Sherrington’s speech at the Nobel Banquet in Stockholm, December 10, 1932

Your Royal Highnesses, Your Excellencies, Ladies and Gentlemen.

I rise in response to the kind toast given by Professor Gunnar Holmgren, and I esteem it a privilege to tender my thanks to him, in this company and in this City renowned for its hospitality, for the generous words which have been spoken. The compliment of the award of a Nobel Prize I value the more since I can interpret it as a sign of sympathetic interest in the efforts of experimental neurology, no less than a generous encouragement to myself.

Several circumstances enhance for me the enjoyment of this visit to Sweden. In the first place it is a pleasure to meet here Swedish scientific men whose names are known the world over, and among them some whom I have known long enough to venture to call them old friends. Then, for one whose study concerns nerves and their activity, it is since nerves express themselves through muscular action, of special interest to visit Sweden with its high tradition of masters in the science of muscular action, for instance Magnus Blix, and Professor Johansson. Further, it is delightful to be associated in this visit with my friend, Professor Adrian, who treats the nerves as a sort of electric power house, and makes even their minutest leakages audible to us. With him we can, so to say, hear the gold fish ‘thinking’, a new fairy-tale for Christmas Eve, now nearly here.

May I take this opportunity to pay a word of tribute on general lines to the work of the Nobel Foundation for the welfare of Science. It must be a difficult thing to adjudicate prizes where so much research and discovery are going on and where so many researchers are deserving. I am sure I am voicing a universal opinion when I say that the considerate care and sympathetic width of view which the Foundation has consistently shown has enhanced the prestige of the Prizes themselves in the eyes of the cultivated world. Its doing so has been a source of deep satisfaction and encouragement to Science itself.

May I remark that a happy and inspiring note in this annual celebration which must have impressed us all in the Concert Hall today is the dignity and charm of the ceremonial observed. Such observance proclaims that Science is worthy of an aesthetic as well as of a purely intellectual setting; and that emphasis is of itself a service to Science.

When we think of Alfred Nobel we cannot but remember that along with his devotion to Science, he was an idealist with lofty ideals. He was, for the thing, an ardent advocate of international friendship and of cooperation between nations. He saw as every thinking man must see, an illustration of the possibilities of that cooperation in the collaboration of scientific researchers the civilized world over in the advance of Science. Nothing can have exemplified better the solidarity of the civilized world in the pursuit of Science than the record of the awards of the Nobel Foundation since their inception a quarter of a century ago. That record instances now this country, now that, often two different countries together, according as the international stream of progress winds. It is the progress of the stream which matters. That holds an added pleasure for each recipient – because each can then feel that his recognition has come to him not in virtue of anything he has done for himself in the sense of for his own sake but because he has contributed a piece – in my case I feel it is a very humble piece – to the advancement of a great common cause. I thank you.

The Nobel Foundation's copyright has expired.