Otto Loewi – Photo gallery

1 (of 2) 1936 Nobel Prize Award ceremony, 10 December 1936. From left: Medicine laureates Otto Loewi and Sir Henry Dale, chemistry laureate Peter Debye, physics laureates Carl David Anderson and Victor F. Hess.

Source: Wellcome Collection. CC BY 4.0 , via Wikimedia Commons

2 (of 2) Sir Henry Dale and Professor Otto Loewi outside the Grand Hotel in Stockholm at the time of the Nobel Week, December 1936

Source: Wellcome Collection. CC BY 4.0.

Sir Henry Dale – Photo gallery

1 (of 2) 1936 Nobel Prize Award ceremony, 10 December 1936. From left: Medicine laureates Otto Loewi and Sir Henry Dale, chemistry laureate Peter Debye, physics laureates Carl David Anderson and Victor F. Hess.

Source: Wellcome Collection. CC BY 4.0 , via Wikimedia Commons

2 (of 2) Sir Henry Dale and Professor Otto Loewi outside the Grand Hotel in Stockholm at the time of the Nobel Week, December 1936

Source: Wellcome Collection. CC BY 4.0.

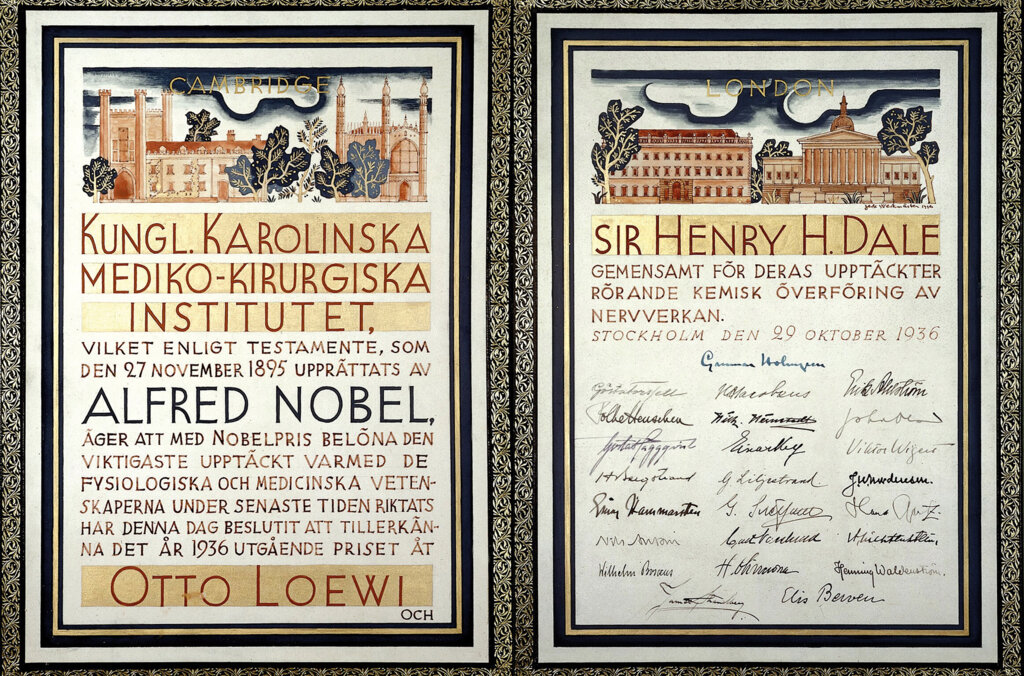

Sir Henry Dale – Nobel diploma

Speed read: Crossing the gap

For the nervous system to receive information from the body and send out instructions, it must rely on finding a way of passing its electrical impulses from one nerve cell to another. By revealing the mode through which impulses communicate their signal across the miniscule gaps, or synapses, that separate nerve cells from each other and from their target destinations, Sir Henry Dale and Otto Loewi received the 1936 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine.

Opinions as to how neurons communicate their signals across synapses were divided between those scientists who believed that the message was electrical, like the nerve impulse itself, and those who believed that chemicals must be involved, because extracts from plants and animals provoked a similar response to nerve stimulation. Otto Loewi’s demonstration that chemicals act as the messenger was beautifully simple. He showed that if the vagus nerve fibres connected to an isolated heart of a frog were stimulated by electricity, it dampened the strength and rate of its heartbeat and a fluid was released. When he collected the fluid and added it to a second frog heart, its heartbeat was affected in exactly the same manner as the first heart without any nerve being fired.

Loewi’s discovery of the nerve-stimulating fluid (he called it vagusstoff) came seven years after Sir Henry Dale had identified a chemical extracted from the fungus ergot, which appeared to stimulate organs in a similar manner. Dale speculated that this chemical, acetylcholine, and Loewi’s vagusstoff were one and the same, and while looking for another chemical in mammals, he discovered that acetylcholine is produced naturally in the body. Developing methods for extracting acetylcholine from animal tissues allowed Dale and his colleagues to carry out a series of experiments that revealed how the chemical works. Among their many findings they showed that acetylcholine acts on many tissues and organs other than the heart, that it is released from nerve endings, and that it is almost immediately destroyed by another chemical once it has carried out its task.

By Sophie Petit-Zeman, for Nobelprize.org

This Speed read is an element of the multimedia production “Nerve Signaling”. “Nerve Signaling” is a part of the AstraZeneca Nobel Medicine Initiative.

Sir Henry Dale – Other resources

Links to other sites

On Henry Hallett Dale from The Royal Institution

Otto Loewi – Nobel Lecture

Nobel Lecture, December 12, 1936

The Chemical Transmission of Nerve Action

Natural or artificial stimulation of nerves gives rise to a process of progressive excitation in them, leading to a response in the effector organ of the nerves concerned.

Up until the year 1921 it was not known how the stimulation of a nerve influenced the effector organ’s function, in other words, in what way the stimulation was transmitted to the effector organ from the nerve-ending. In general it was thought that it came about through direct transmission of the stimulation wave from the nerve fibre to the effector organ. But the possibility of transmission by chemical means had also been considered and experiments had been conducted on these lines. As a result of his own experiments, Howell1 had come to believe that vagus stimulation released potassium in the heart and that this was the cause of the resultant effect, and Bayliss2 discussed the possibility, in view of the similarity in action of the so-called vagomimetic substances and chorda stimulation, that this stimulation might be caused by the production of such substances. Although these data were known to me, my attention was only drawn years after my discovery to the fact that earlier (in 1904 to be exact) Elliott3, in the last paragraph of a short note, suggested the possibility that the stimulation of sympathetic nerves might be brought about by the release of adrenaline, and that Dixon4 had already communicated experiments in an inaccessible site to test whether, during vagus stimulation, a substance was released which contributed to the stimulation reaction.

In the year 1921 I was successful for the first times in obtaining certain proof that by stimulation of the nerves in a frog’s heart substances were released which to some extent passed into the heart fluid and, when transferred with this into a test heart, caused it to react in exactly the same way as the stimulation of the corresponding nerves. In this way it was proved that the nerves do not act directly upon the heart, but rather that the direct result of nerve stimulation is the release of chemical substances and that it is these which bring directly about characteristic changes of function in the heart.

It was, of course, possible right from the start that this mechanism which I described at the time as “humoral transference”, but which is now known as “chemical” transference as the result of a well-founded suggestion by H.H. Dale, does not represent an isolated phenomenon but a special condition which also appears elsewhere. We shall soon see that this supposition was justified. But before I go into that I should like to characterize in more detail the substances which are released by nerve stimulation and produce the effect. First of all, I must mention my distinguished collaborators E. Navratil, W. Witanowski, and E. Engelhart, and thank them.

Let me begin with the transfer medium of the reaction in vagus stimulation which I have called “vagus substance”. We were able to determine that its effect is inhibited by atropine5 and very quickly disappear6. In looking for a substance with both these characteristics, I found that out of a series of the known vagomimetic substances, muscarine, piloearpin, choline, and acetylcholine, only the last-named possessed them7. We were then able to establish further that the rapid disappearance of the action of the vagus substance and acetylcholine (Ac.Ch.) through the breaking down of these substances was caused by the action of an esterase in the heart6, which had already been postulated by Dale8. I was able to show furthermore that the action of this esterase could be specifically inhibited through minimum concentrations of eserine7. This discovery was important not only because, for the first time, the operational mechanism of an alkaloid had been revealed, but especially because the discovery enabled the theory of the chemical transference of nerve stimulation to be developed for the first time. On the one hand, this eserine action provided a means of revealing the minimal quantities of Ac.Ch. being released by nerve stimulation which would otherwise, because of their rapid destructibility, have remained undisclosed. On the other hand, we are able, in cases where for any reason it is technically impossible or difficult to prove directly the release of Ac.Ch. in nerve stimulation, to draw the conclusion indirectly from the increase in effect of nerve stimulation after previous eserination that the nerve stimulation is being produced by the release of Ac.Ch. And now we must return to the characterization of the vagus substance.

The vagus substance behaves identically with Ac.Ch. not only in regard to its reaction to atropine, and to its destructibility with esterase but also concerning all other characteristics. As Dale and Dudley9 were able to produce it directly from the organs, there can be no more doubt that the vagus substance is Ac.Ch. and in future I shall refer to it as such.

As regards the character of the substance which is released through stimulation of the sympathetic nerves of the heart and other organs, I was able to show earlier that it shares many properties with adrenaline; both, for example, are destroyed by alkali20 and by fluorescence and ultraviolet light6, the activity of both is abolished by ergotamine21; on the other hand, as Cannon and Rosenblueth10 have shown, it is raised by small and in themselves ineffective quantities of cocaine, the adrenaline-sensitizing action of which Fröhlich and I11 found some 25 years ago.

Like the effect of adrenaline, an equal effective strength of the sympathicus substance declines very slowly in the heart, much more slowly incidentally than might have been expected in view of the rapid oxidizability of adrenaline or sympathicus substance in vitro. The cause of this, as revealed by Dr. Ralph Smith of Ann Arbor and me in a series of specially conducted experiments not as yet published, turns out to be the giving off of substances from the heart which inhibit adrenaline oxidation. There must, of course, be some physiological purpose in the fact that individual devices exist, on the one hand to remove the acetylcholine as quickly as possible and the adrenaline, on the other hand, as slowly as possible. And now we must return to the chemical nature of the sympathicus substance.

Although for some time it had been considered probable after all we had seen that the sympathicus substance was adrenaline, I was only able to give direct proof of it this year. Gaddum and Schild13, on the basis of a statement by Paget, investigated the significance of a green fluorescence visible in ultraviolet light which pointed to adrenaline in the presence of O2, and alkali, and found that this appears to a high degree specific for adrenaline. I was now able to show that not only the heart extract, but also the heart fluid, shows this reaction after accelerated periods of stimulation12. Accordingly I consider it proved that the sympathicus substance is adrenaline.

Now I must briefly consider the question of to what extent the neuro-chemical mechanism, that is to say the chemical transference of nerve stimulation, is important other than to the heart.

Firstly, Rylant14 and others were able to show that with warm-blooded animals too, vagus stimulation released Ac.Ch. which was responsible for the resultant stimulation reaction. I must mention in this connection that my collaborator Engelhart15 was able to show, in accordance with the well-known fact that the heart vagus in warm-blooded animals ends at the auricular/ ventricular boundary, that here considerably more Ac.Ch. was to be found before and after stimulation in the auricle than in the ventricle, whereas in a frog’s heart, where the vagus extends over the ventricle as well, the distribution of Ac.Ch. over auricle and ventricle is even. As the heart vagus belongs to the parasympathetic system, the question had to be examined whether and to what extent the neurochemical mechanism applied here. The first investigation on this point also came from my Institute, from Engelhart16 , who was able to prove the release of Ac.Ch. as a result of stimulation of the oculomotor nerve. The total result of the many different, resultant investigations on various organs can be summarized by saying that up until now no single case is known in which the effect of the stimulation of the parasympathetic nerves was not caused by the release of Ac.Ch.

As, to my mind, a lecture should concern itself not only with results, but also with still open questions, I must touch on the following: As all activity caused by the application of Ac.Ch. can be halted by atropine, one might expect that wherever Ac.Ch. is released as a result of nerve stimulation, the effect could everywhere be halted by atropine. This, however, is not so. Contractions of the bladder after stimulation of the pelvic nerve, dilation of the vessels of the salivary gland after stimulation of the chorda nerve still occur even after atropinization. And here we must mention the following strange observation by V.E. Henderson17: he found that after preliminary atropinization, vagus stimulation in the intestine produced no increase of tonus, but an increase of peristaltic contractions. The reason for these remarkable exceptions has so far escaped us.

The neurochemical mechanism is everywhere apparent in the field of activity of the parasympathetic system, as in the sympathetic system. But we have Dale18 and his collaborators to thank for the recognition that the stimulation of certain nerve fibres which belong anatomically to the sympathetic system lead to the release, not of adrenaline, as in the overwhelmingly large number of cases, but of Ac.Ch.

To sum up then, it may be said that the neurochemical mechanism applies in the stimulation of all autonomic nerves.

But it also embraces a much wider area. We owe this knowledge in the main to the basic investigations of Dale. There is no need, therefore, for me to go further into this in my lecture.

We now have to discuss the important question of whether the nerve stimulation influences only the function of the effector organ by the release of nerve substances, as I will call the chemical transmitters for the sake of briefness, or whether it perhaps exerts another influence as well.

Here we shall be well advised to take as a starting-point the mechanism of action of atropine or ergotamine. With Navratil19 I was able to show (and this finding was confirmed many times over) that these alkaloids do not, as had been thought previously, attack and incapacitate the nerves themselves. We were able to show this by demonstrating that even after using atropine and ergotamine, nerve stimulation still released nerve substances. This shows that atropine and ergotamine do not impair the function of the nerves, which is a liberating one, that is to say, they do not paralyse the nerves, but exert an antagonistic influence on the action of the substances produced. By recognizing that after previous application of atropine or ergotamine the stimulation of the respective nerves is known to have no effect at all upon the effector organ, it has been proved that nerve stimulation has no other effect but to release nerve substances. What other kind of function can remain for the nerve if the action of the substance released coincides absolutely with the effect of the nerve stimulation? Although what follows is self-explanatory, I still think it desirable to state it expressly: in all cases in which the neurochemical mechanism occurs, the nerves only control function to the extent of the release of the substance: the place where this occurs is in the effector organ of the nerve. From then onwards, the released substance exerts control: the functioning organ is, therefore, its effector organ exclusively.

And now we must consider in which directions our knowledge of the physiological process has been extended, beyond what we have already said, by the discovery of the neurochemical mechanism.

There will be no cause for argument if we see the most importance in the fact that at last a clear answer has been found to the age-old question as to the nature of the stimulus-transfer from nerve to effector organ.

Next in importance appears to me to be the explanation of the nature of the peripheral inhibition. Up until now, it appeared quite inconceivable that the stimulation of a nerve could lead to inhibition in the effector organ. With the proof that this inhibition comes about because the nerve releases a function-inhibiting substance, the reason for it becomes clear. At the same time, however, something else is proved which seems to me to be of great importance: the release of a substance by the nerves is the expression of a positive function, an activation. This proves that the direct effect of the stimulation of all nerves, whether activating or inhibitory, represents a promotion of function, for this is what the release of the substance does.

Today, because we know how it happens, this solution strikes us as self-evident. For, since the process of stimulation is, to a certain degree, unspecific and furthermore interference in stimulus frequencies which certainly form the basis of some inhibitory manifestations in the animal region of the central nervous system cannot, in the case of peripherally inhibitable organs, be regarded as the cause of inhibition, I see no other possibility, at least in general, as to how nerve stimulation can lead to inhibitions of the effector organ at all than by chemical means; in other words, the chemical mechanism is the only conceivable way.

So much for the field of activity and the importance of the neurochemical mechanism.

After this description which touches upon the general nature only of the neurochemical mechanism, we will now consider more exactly its finer mechanism.

First of all the question arises: where are the substances released by nerve stimulation localized, or, in other words, where is the point of attack of the nerve stimulation? A priori, two possibilities exist: the substances are released in the nerve endings or in the effector organ. Investigations of this question carried out so far are concerned only with Ac.Ch.

For the time being we shall only draw upon findings which concern the Ac.Ch. content of organs after nerve degeneration.

As far back as 30 years ago, Anderson22 observed the following: after degenerative division of the oculomotor nerve, light stimulation was for a long time without effect, regardless of whether the eye had been eserinized or not. There followed a period when light stimulus was still ineffective to the uneserinized eye, but not to the eserinized eye. At this moment, as could be shown, a weak regeneration of the oculomotor nerve had begun. In Anderson’s time it was not possible to give an adequate explanation of these findings. Today, when we know that oculomotor stimulation releases AC.Ch., the action of eserine is revealed as being simply to increase the effect of the Ac.Ch. by inhibiting that of the esterase, and Anderson’s results become absolutely clear. With degeneration of the oculomotor nerve the Ac.Ch. disappears. Eserine then also becomes ineffective. With the start of regeneration of the oculomotor nerve the Ac.Ch. appears again, but in too small quantities to cause miosis with light stimulus alone, i.e. without the increased activity provided by eserine. Thus Anderson’s experiments provide the first proof that the existence of Ac.Ch. in the eye is dependent upon the nerves. Later Engelhart16 in my own Institute produced this proof in a direct manner. With direct Ac.Ch. determination he found that after degeneration of the oculomotor nerve in corpus ciliare and iris, the Ac.Ch., present in considerable quantities in preserved nerves, completely disappears. This shows that, in many organs at any rate, the Ac.Ch. content and its maintenance is connected with the presence of the nerve. There are two possible explanations for the disappearance of the Ac.Ch. after nerve degeneration. Either the Ac.Ch. is a part of the nerve and disappears then naturally with its degeneration, or it belongs to the effector organ. Then we should have to assume that the formation and maintenance of the Ac.Ch. amount in the effector organ was, in some mysterious and trophic manner, dependent upon the nerve, so that it would disappear with its degeneration. Should the Ac.Ch. be a product of the effector organ and not the nerve ending, then, according to Dale, it would have to disappear, after degeneration, through some kind of atrophy. This hypothesis would then require a further subhypothesis, that of separate and specific transmission system in the effector organ quite unlike any other. This assumption would be necessary, because, after oculomotor nerve degeneration, the effector organs, corpus ciliare and iris do not degenerate, and yet the Ac.Ch. disappears. The influence of the oculomotor nerve degeneration must, in that case, only extend to the mysterious transmission system. In respect of these difficulties alone, a far likelier assumption is that the Ac.Ch. which is released by nerve stimulation belongs to the neurone itself, or more exactly to the nerve ending. There is in my opinion, in at least one instance, compelling proof for the correctness of this supposition.

In Dale’s Institute, Feldberg and Gaddum23 have shown that stimulation of the preganglionic sympathetic fibres in the neck releases Ac.Ch. in the sup.cerv. ganglion, which itself stimulates the ganglion, so that progressive stimulation is set up in the postganglionic fibres. In elegant experiments directed towards the question of the localization of the release of Ac.Ch. in the ganglion, Feldberg and Vartiainen24 were recently able to prove that it was released neither by the preganglionic fibres nor by the ganglion cells themselves, the only direct effector organ. They concluded, therefore, that the Ac.Ch. was produced in the synapse. Synapse is not an anatomical but a purely functional concept. It indicates the spot where the nerve ending comes into contact with the cell, and has been adopted by histologists only in this sense. If, therefore, it can be proved that Ac.Ch. is formed in the “synapse”, it can only, in my opinion, be in the preganglionic nerve ending or in the ganglion cell. As the ganglion cell can be ruled out, as Feldberg and Vartiainen have shown, there only remains, it appears to me, the nerve ending as the site of release. Although proof of this has so far only been obtained directly in the case of preganglionic sympathetic endings, there is, nevertheless, much to make us think that in other places as well the nerve substances are released in the nerve endings themselves. We know that in many organs by no means each single, functioning unit is accorded a nerve fibre. At most, according to Stöhr, one occurs for every hundred capillaries. When the nerve is stimulated, however, all react. In these cases, how does the nerve substance diffuse to those regions without nerves? I believe that the nerve ending is here the liberation centre. This supposition is supported when we consider that when the autonomous nerves are stimulated the two same substances are always released in very different organs having a quite different chemical structure and accordingly undergoing quite different chemical changes. If the substances were not being released in the nerve endings, but peripherally of them, then we should again have to assume the presence of some mysterious mechanism capable of transferring the stimulation of the nerve ending to the supposed peripheral position where the substance would be released; in which case, the discovery of the neurochemicalmechanism would not, in my opinion, represent any important progress.

We come now to the next question concerning this delicate mechanism.

So far we have only spoken of the release of the substance from the nerve ending. This is only to say that a free nerve substance emerges from the nerve ending. But it is important for an understanding of the nature of nerve function to know what exactly we should imagine is implied by this release. A priori the following possibilities exist: either the substances are not present in the nerve ending when the nerves are in a state of rest and are only formed by nerve stimulation and, once formed, diffuse, or they are already present in the state of rest, but can only diffuse after stimulation. As regards the formation of nerve substances through the nerves, it is certain that this can be done. Even Witanowski25 in his day found Ac.Ch. in the vagus, in the sympathicus and in the sympathetic ganglia. The last two findings were confirmed by Chang and Gaddum.26 As Ac.Ch. is not present in the blood, it cannot diffuse from there, and neither, on account of its ready destructibility, could it diffuse from elsewhere in the nerves and ganglia. The same applies for adrenaline. Recently we have succeeded in showing the presence of adrenaline in a frog’s brain in a state of rest or even anaesthetized, and also in the upper cervical ganglia of cattle. It was characterized by its effect upon the heart which was similar to that of adrenaline, through the neutralizing of this effect by ergotaminization and also by its destructibility through fluorescent light. These findings, therefore, confirm that the nerve substances are formed by the nerve and are present even in a state of rest. Whether the nerve, when stimulated, produces further substance as well is another still undecided question which we are not touching upon here. However interesting in itself the answer to this question may be, it does not appear to me to be of essential importance, since the basic effect of nerve stimulation is the release of the substances. There are two possibilities as regards the processes of release and diffusion: either the substances are present in a free and diffusible state in the nerve ending, but the nerve ending when in a state of rest is impermeable and only made permeable to them after stimulation, when they become diffusible and effective, or, the substances in the resting state are in some way combined and indiffusible and only the stimulation releases the combination and thereby makes them diffusible and effective. If the first possibility were to apply, then we must not find the Ac.Ch. at all, since, as has been shown, esterase is found everywhere in the nerves and this, as we shall soon see, destroys the free Ac.Ch. But we do find it in the nerve. This fact alone suffices to show that it is not present in a free, diffusible state in the nerve ending. In addition, Bergami28 recently found, in confirmation of earlier experiments by Calabro27, that Ac.Ch. only issues from the free end of severed nerves if the nerve is stimulated. In this case, the release cannot, of course, be attributed to any change in the state of permeability brought about by stimulation, since the free nerve ending has no membrane. The second possibility which I mentioned earlier must apply, namely that the Ac.Ch. in the unstimulated nerves is bound in some way and thereby protected from the assault of the esterase. In fact, it is present in such quantity in hearts where there is no vagus stimulation, that in a freely diffusible state it would be more than sufficient to stop the heart altogether. On its own it is ineffectual and is protected against the action of the esterase, in contrast to when it is in a diffusible state.

In experiments directed towards the study of this question Engelhart and I29 found the following: If one determines the initial value of Ac.Ch. in a heart section, leaving the remaining portion of the heart intact for a few hours, as much Ac.Ch. is found in it afterwards as in the beginning. Dale and Dudley, incidentally, found the same in the case of the spleen. In an organ in a state of rest, therefore, the Ac.Ch. is protected against the esterase. But if free (that is to say diffusible) Ac.Ch. is added to a heart in a state of rest, it is destroyed. All this goes to show that obviously, as Dale also assumed, the Ac.Ch. is present in the organ in a state of rest in some kind of loose, non-diffusible combination, and for that reason it is non-susceptible to attack by esterase and non-effective. Such combinations we know do very often occur in an organism. The so-called “vehicle function” of the blood implies in fact no more than the ability of the blood’s component parts to bind substances and, when necessary, to release them. But the binding must in any case be a very loose one, as after destroying the structure, for instance by mincing the organ, the Ac.Ch. is very quickly destroyed by esterase. Nerve stimulation would accordingly appear to have the effect of releasing from this combination the Ac.Ch. which has been proved to be present in the nerve.

The same applies also for the nerve substance in the sympathetic system, adrenaline. As I was able to show this year12, the heart contains 1 gamma to 2 gamma per gram, which corresponds to a concentration of 1:1 million to 1:500,000. Whereas adrenaline added to the heart will already be effective in a concentration of 1:100 million to the maximum, the concentration of 100-200 times more adrenaline in a heart in a state of rest will be without effect. Therefore it also must be present in some kind of inactive combination in the heart. This fact also seems to me to be of importance in the possible interpretation of certain other findings. It is known that in many organs the adrenaline action is quickly over. Up until now this has been explained by the speedy oxidation of adrenaline. This is certainly the case for pure adrenaline solutions in vitro. In vivo, on the other hand, adrenaline is not only not easily oxidized, but all the organs contain substances – among them, as has been proved, amino acids – which, even in minimal quantities, have a direct inhibiting effect upon the oxidation of adrenaline. How then does this rapid cessation of activity come about? It may, in part, be due to counteractions. In some cases, however, the disappearance of activity could be due to rapid transference of the adrenaline into an ineffective linkage as is to be found in the heart.

Now let us return from this digression to the subject of the release of the nerve substances. This occurs very quickly and the action of the released nerve substance is very rapid also, although between release and effect the diffusion process has also to be set in motion. The time interval varies in length in different cases, but is in part certainly dependent upon the distance of the releasing nerve ending from the effector cell. According to Brown and Eccles30 this is 80-100 omega in the case of the heart, but only 2 omega in the ganglionic synapse. This must mean that release coincides with stimulation. Dale is able to explain quite easily the fact that the effect reaches the ganglion cell almost without any time lapse by the fact that the release in the nerve ending occurs directly with contact with the ganglion cell, whereas in the heart, where incidentally the first contraction after vagus stimulation is smaller, a certain time is required for diffusion to the effector cells. As in the case of release and effect, the speed with which the substance and with it the effect disappears, varies in different objects. The discovery of the chemical mechanism of the effect of vagus stimulation in the heart was only possible because in this case the destruction of the Ac.Ch. occurs so slowly that the substance had time to diffuse, in sufficient quantity to be active, into the heart; in the ganglia on the other hand, the destruction occurs so rapidly that the Ac.Ch. in the perfusion fluid is only demonstrable after preliminary eserination. The differences in time between freeing and disappearance in both cases are easily understandable if we consider the quite different purposes which the nerve stimulation serves in both these cases.

And now, finally, we come to the localization of the point of attack of the nerve substances.

As long as it was not known that the autonomic nerves, when stimulated, release substances which condition the successful effect of the nerve stimulation, it was assumed in general, in consideration of the fact that the action picture of the so-called vago- and sympathico-mimetic substances is identical with the stimulating of the corresponding nerves, and, further, with the fact that it was believed that the alkaloids, atropine, and ergotamine, which inhibit the action of the substances, paralyse the corresponding nerves, that the vago- and sympathico-mimetic substances stimulate the nerves somewhere peripherally. But as they are effective even after nerve degeneration, it was assumed, with justification at the time, that a non-degenerative myoneural junction was the point of attack. Today, now that we know that the nerves do release nerve substances, this view is no longer tenable. The nerve substances, considered as vago- or sympathico-mimetic substances, would have to act like these, that is to say, they would have to stimulate the myoneural junction and release substances, etc. on their own. In this case there would be no kind of effect upon the effector organ. Quite apart from this, the supposition that the nerve substances stimulate the nerve somewhere is quite superfluous by the proof shown above, that the alkaloids atropine and ergotamine which inhibit the activity of the vago- and sympathico-mimetic substances, do not, as was supposed, paralyse the nerves, but are simply antagonistic to the substances. If all this is evidence against the nerve as point of attack, it has also been proved that Ac.Ch. and adrenaline are also effective in the absence of nerves. Ac.Ch., for instance, dilates vessels which are not parasympathetically innervated. Adrenaline increases the activity of the still nerveless embryonic heart and stimulates the arrectores pilorum, which, according to Stöhr, are also nerveless, etc. Therefore, the point of attack of the nerve substances must be some part of the effector organ itself, probably chemical or chemico-physical in character and not morphological.

As Dale has proved, we can no longer say that the nerve substances reproduce the action picture of the nerves but rather it is a fact that the nerves reproduce the action picture of the substances, since they release these and thus lead to effective action. That the activity caused by any one nerve substance appears principally at the spot where it is released, that is to say, that in that particular spot the cells are receptive to its action, is a local phenomenon of the specific sensitivity to certain chemical substances which is met with everywhere in the living organism and which is Erie of the foundations of its function and, therefore, of its very existence and which can only be understood teleologically and not causally; think, for example, of the finely graduated, specific sensitivity of the respiratory centre to CO2.

Up until now we have discussed only the effect of the nerve substances on the organ in which they are released through nerve stimulus. Are they only active there, or in other distant organs too? We have already mentioned that a part of the released substance diffuses into the blood or into some other perfusing fluid. This could present the possibility of its action being extended to other more distant organs. What is the position here? Given special conditions, which I would like to characterize as pathological, this could happen.It has been proved that when the breaking up of the Ac.Ch. by an esterase, is inhibited by eserine, the Ac.Ch. penetrates with the blood to other organs in sufficient quantities to cause activity. Furthermore, Cannon31 by preliminary sensitizing of organs through denervation, or cocainization, made them so hypersensitive to the sympathicus substance that they reacted to its release in any organ. In the same way as in these experimentally induced disturbances, it could also happen perhaps that in cases of illness, the release of surplus quantities of substance or incomplete destruction may interrupt the normal release and destruction, leading to hypersensitivity of organs and the appearance of effect at a distance. It would be very desirable if in future clinicians would give consideration to these relationships with a view to explaining certain symptoms and groups of symptoms which until now, partly without sufficient foundation, have been considered as purely reflex. Under normal conditions, however, the effect of the nerve substance would be limited to the organ in which it is released. The hormones are there to exert a general control, that is to say not a localized chemical one, on the organs.

In conclusion a word or two on the question of how the neurochemical mechanism fits into the connecting pattern of cells. With the discovery that its influence comes about through substances which are released by the nervous system itself, we have the first proof that the nervous system is not only an effector organ for chemical influences from outside, and not only a participant in general metabolism, but that it has itself a specific chemical influence upon happenings in the organism. On closer examination this is not surprising.

In nerve-free multicellular organisms, the relationships of the cells to each other can only be of a chemical nature. In multicellular organisms with nerve systems, the nerve cells only represent cells like any others, but they have extensions suited to the purpose which they serve, namely the nerves. Accordingly it is perhaps only natural that the relationships between the nervous system and other organs should be qualitatively of the same kind as that between the non-nervous organs among themselves, that is to say, of a chemical nature.

1. W.H. Howell, Am. J. Physic., 21 (1908) 51.

2. W.M. Bayliss, Principles of General Physiology, 3rd ed., 1920, p. 344.

3. T.R. Elliott, J. Physiol., 31 (1904) 20 P.

4. W.E. Dixon, Med. Mag., 16 (1907) 454.

5. O. Loewi, Pflügers Arch. Ges. Physiol., 189 (1921) 239.

6. O. Loewi and E. Navratil, Pflügers Arch. Ges. Physiol., 214 (1926) 678.

7. O. Loewi and E. Navratil, Pflügers Arch. Ges. Physiol., 214 (1926) 689.

8. H.H. Dale, J. Pharmacol., 68 (1924) 107.

9. H.H. Dale and H.W. Dudley, J. Physiol., 68 (1929) 97:

10. W.B. Cannon and A. Rosenblueth, Am. J. Physiol., 99 (1932) 392.

11. A. Fröhlich and O. Loewi, Arch. Exptl. Pathol. Pharmakol., 62 (1910) 159.

12. O. Loewi, Pflügers Arch. Ges. Physiol., 237 (1936) 504.

13. J.H. Gaddum and H. Schild, J. Physiol., 80 (1934)9 P.

14. P. Rylant, Compt. Rend. Soc. Biol., 96 (1927) 1054.

15. E. Engelhart, Pflügers Arch. Ges. Physiol., 225 (1930) 722.

16. E. Engekart, Pflügers Arch. Ges. Physiol., 227 (1931) 220.

17. V.E. Henderson, Arch. Intern. Pharmacodyn., 27 (1922) 205.

18. H.H. Dale, J. Physiol., 80 (1933) 10P.

19. O. Loewi and E. Navratil, Pflügers Arch. Ges. Physiol., 206 (1924) 123. E. Navratil, Pflügers Arch. Ges. Physiol., 217 (1927) 610.

20. O. Loewi, Pflügers Arch. Ges. Physiol., 193 (1921) 201.

21. O. Loewi, Pflügers Arch. Ges. Physiol., 203 (1924) 408.

22. H.K. Anderson, J. Physiol., 33 (1905) 156, 414.

23. W. Feldberg and J.H. Gaddum, J. Physiol., 81 (1934) 305.

24. W. Feldberg and A. Vartiainen, J. Physiol., 83 (1934) 103.

25. W.R. Witanowski, Pflügers Arch. Ges. Physiol., 208 (1925) 694.

26. H.C. Chang and J.H. Gaddum, J. Physiol., 79 (1933) 255.

27. Q. Calabro, Riv. Biol., 19 ( 1935).

28. G. Bergami, Klin. Wockschr., 15 (1936) 1030.

29. E. Engelhart and O. Loewi, Arch. Intern. Pharmacodyn., 38 (1930) 287.

30. G.L. Brown and J.C. Eccles, J. Physiol., 82 (1934) 211.

31. W.B. Cannon and Z.M. Bacq, Am. J. Physiol., 96 (1931) 392.

Otto Loewi – Banquet speech

Otto Loewi’s speech at the Nobel Banquet in Stockholm, December 10, 1936 (in German)

Königliche Hoheiten, Excellenzen, meine Damen und Herren!

Grosse Menschen stehen nicht nur im Leben, sondern auch über dem Leben, übersehen von da die Zusammenhänge und erkennen, was der Menschheit eignet und was ihr noctut. Ein solcher Mensch war Alfred Nobel und so erkannte er das Bedürfnis der Menschenzukunft: Zusammenwirken Aller zum grösstmöglichen Wohle Aller. In der Erkenntnis, dass das nur durch maximale Anspannung der besten Kräfte erreichbar ist, verwirklichte er seine Maxime durch eine geniale Tat so weit, als dies für einen Menschen möglich ist.

Voraussetzung hierfür war, das Alfred Nobel, als Schwede, wusste, dass es hier immer Menschen geben würde, die grösstes Verantwortungsgefühl für ihr schweres Richtcramt besässen. Und er hat richtig vorausgesehen. Das Nobelkomite ist ein idealer Verwalter des ideellen Erbes Alfred Nobels: Beweis dafür ist, dass auch heute noch, 35 Jahre seit der erstmaligen Verleihung des Preises, diese als höchste wissenschaftliche Adelung gilt. An dem Fest dieser Adelung nimmt, mit Seiner Majestät dem König und dem Königlichen Haus an der Spitze, ganz Schweden teil. Welch ein Volk, dessen vielleicht höchstes Fest, ein Fest der Wissenschaft und der Kultur ist! Das gibt Hoffnung und Zuversicht, denn solange so etwas möglich, kann es um die Welt nicht so schlecht bestellt sein.

Adel verpfichtet; und so ist sein Träger verpflichtet aus tiefstem Herzen dankbar dafür zu sein, dass er, der ohnehin das grosse Glück hat sein ganzes Leben der Leidenschaft nach Erkenntnisvermehrung widmen zu dürfen, dafür am Ende auch noch belohnt wird. Das muss ihn gleichzeitig stolz und demütig machen.

Und nun etwas mehr Persönliches: das erste mal betrat ich das herrliche, gastliche Schweden 1926. Damals durfte ich dem Internationalen Physiologen-kongress den Grundversuch der Arbeit vorführen, um derentwillen ich nunmehr den Preis empfing. Meine Mussestunden widmete ich dem genauen Studium des Meisterwerkes Ragnar Östbergs, des herrlichsten Profanbaues der Moderne: des Stadthauses. Immer und immer zog es mich wieder dahin. Und als ich mir über den Grund dieser unwiederstehlichen Anziehungskraft klar zu werden suchte, fand ich ihn darin, dass dieser Bau die edelste Tradition der Vergangenheit, mit grösster Aufgeschlossenheit für bestes Gegenwärtiges und Künftiges eint. Jedes Volk hat die Kunst, die seinem Wesen entspricht. Ich danke aus tiefstem Herzen für das Glück dass ich diese Einheit jetzt nicht mehr nur künstlerisch, sondern menschlich hier erleben darf.

Sir Henry Dale – Nobel Lecture

Nobel Lecture, December 12, 1936

Some Recent Extensions of the Chemical Transmission of the Effects of Nerve Impulses

The transmission of the effects of nerve impulses, by the release of chemical agents, first became an experimental reality in 1921. In that year Otto Loewi published the first of the series 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6 of papers from his laboratory, which, in the years from 1921-1926, established all the principal characteristics of this newly revealed mechanism, so far as it applied to the peripheral transmission of effects from autonomic nerves to the effector units innervated by them. Of the general history of this discovery, of the speculations which preceded it, and of its more recent developments in detail in many laboratories, as regards one aspect of it particularly by Cannon and his co-workers in Boston, you have heard from Professor Loewi himself. I propose to deal with a wider application of this conception of chemical transmission, which has resulted from researches carried out during the past three years in my own laboratory, by a number of able investigators – J.H. Gaddum, W. Feldberg, A. Vartiainen, Marthe Vogt, G.L. Brown, Z.M. Bacq. These investigations have made it possible to suggest that a fundamentally similar chemical mechanism is concerned in the transmission of excitatory effects at the synapses in all autonomic ganglia, and at the motor nerve endings in ordinary, voluntary muscle.

You will see that, according to this relatively new evidence, a chemical mechanism of transmission is concerned, not only with the effects of autonomic nerves, but with the whole of the efferent activities of the peripheral nervous system, whether voluntary or involuntary in function. This extension of the principle of chemical transmission has come as a surprise to many; the relative ease, with which the evidence justifying it can be obtained, has been surprising to ourselves. But the basic conception, which encouraged us to undertake experiments in this direction, was no novelty to me; and for its origin I must ask you to look briefly at some experiments which I had already made and published in 19147 . My chemical collaborator at that time, Dr. Ewins8, had isolated the substance responsible for a characteristic activity which I had detected in certain ergot extracts, and it had proved to be acetylcholine, the very intense activity of which had been observed by Reid Hunt9 already in 1906. Since we had found this substance in nature, and it was no longer merely a synthetic curiosity, it seemed to me of interest to explore its activity in greater detail. I was thus able to describe it as having two apparently distinct types of action. Through what I termed its “muscarine” action, it reproduced at the periphery all the effects of parasympathetic nerves, with a fidelity which, as I indicated, was comparable to that with which adrenaline had been shown, some ten years earlier, to reproduce those of true sympathetic nerves. All these peripheral muscarine actions, these parasympathomimetic effects of acetylcholine, were very readily abolished by atropine. When they were thus suppressed, another type of action was revealed, which I termed the “nicotine” action, because it closely resembled the action of that alkaloid in its intense stimulant effect on all autonomic ganglion cells, and, as later appeared, on voluntary muscle fibres. I am tempted here to quote some words which I wrote in that paper, in 1914.

“It is clear, then, that the distinction between muscarine and nicotine activity cannot be made with absolute sharpness… Nor is there any evidence enabling us to regard one group of the molecule as responsible for the one type of action, and another for the other. One can merely conclude that there is some degree of biochemical similarity between the ganglion cells of the whole involuntary system and the terminations of voluntary nerve fibres in striated muscle, on the one hand, and the mechanism connected with the peripheral terminations of craniosacral involuntary (i.e. parasympathetic) nerves on the other.”

In the same paper I had speculated on the possible occurrence of acetylcholine in the animal body, and on its physiological significance if it should be found there; and had pointed out the extraordinary evanescence of its action, suggesting that an esterase probably contributed to its rapid removal from the blood.

When, therefore, some seven years later, Loewi described his beautiful experiments, showing that stimulation of the vagus nerve produced its inhibitor effects on the frog’s heart by the liberation of a chemical substance; and when his successive papers provided cumulative evidence of the similarity of this substance to acetylcholine, including its extreme liability to destruction by an esterase, which Loewi extracted from the heart muscle; I believe that I was more ready than most of my contemporaries for immediate acceptance of the evidence for this “Vagusstoff”, and more eager, almost, than Professor Loewi himself, to assume its identity with acetylcholine. There was wanting, it seemed to me, only one item of evidence to justify certainty as to the nature of this substance, namely, a proof that acetylcholine itself, and not merely some choline ester of closely similar properties, was an actual constituent of the animal body.

Professor Loewi has already mentioned the extraction and identification of acetylcholine, as a natural constituent of a mammalian organ, by my late and deeply lamented colleague, H.W. Dudley, and myself10, in 1929. He has also dealt with the general rule that parasympathetic effects are transmitted by acetylcholine, and true sympathetic effects by what his own most recent experiments appear definitely to identify as adrenaline. He has mentioned also the important exceptions to that rule. In view of such exceptions, it seemed to me desirable to have a terminology enabling us to refer to a nerve fibre in terms of the chemical transmission of its effects, without reference to its anatomical origin; and, on this functional basis, I11 proposed to refer to nerve fibres and their impulses as “cholinergic” or “adrenergic”, as the case might be. Such a functional terminology seemed to me the more important, in view of the evidence which was already coming from our experiments, that acetylcholine had a much wider function as a transmitter of nervous excitation, than that concerned with the post-ganglionic fibres of the autonomic system, and their effects on involuntary muscle and gland cells. For all such effects of acetylcholine, directly analogous to those which Loewi discovered in relation to the heart vagus, were covered by what I had termed the “muscarine” action of acetylcholine, and were all very readily suppressed by atropine. But there remained, as yet without any corresponding physiological significance, the other type of action of acetylcholine, so similar in distribution to that of nicotine, which had come to my notice nearly twenty years earlier. Was it credible, I asked myself, that this sensitiveness of ganglion cells, and of voluntary muscle fibres, to the substance now known to be the transmitter of peripheral parasympathetic effects, was entirely without physiological meaning? I could not believe it. At the same time, it had to be recognized that the transmission of nervous excitation at ganglionic synapses, and at motor nerve endings in voluntary muscle, was a phenomenon of a different order from any of those in connexion with which the intervention of a chemical transmitter had hitherto been demonstrated, or even considered. Acetylcholine, released at the peripheral endings of the vagus or the chorda tympani, could be pictured as reaching the heart cells or those of the salivary gland by diffusion, and there inhibiting an automatic rhythm, or exciting glandular secretion. At a ganglionic synapse or a motor ending on a voluntary muscle fibre, on the other hand, the evidence was clear, that a single impulse, reaching the end of the preganglionic or motor nerve fibre, caused the passage from the ganglion cell, along its post-ganglionic axon, of a single nerve impulse, and no more; or caused the passage, from the motor end plate of the muscle fibre, of a single wave of excitation, of propagated contraction, and no more. In both cases, the phenomenon had the appearance of a direct, unbroken conduction, to ganglion cell or muscle fibre, of the same propagated wave of physico-chemical disturbance as had constituted the preganglionic or the motor nerve impulse, with only a slight, almost negligible retardation in its passage across the ganglionic synapse or the neuromuscular junction. And, indeed, such continuity of the conduction, in both cases, had generally been assumed, and, in the case of the neuromuscular conduction, in particular, had been implicit in the interpretation of a great body of detailed evidence, which the ingenuity and the labours of two generations of physiologists had produced.

Could the stimulating action of acetylcholine on ganglion cells and on muscle fibres, its “nicotine” actions, be pictured as intervening in these rapid and strictly limited transmissions of excitation across ganglionic and neuro-muscular synapses? We could only imagine such intervention, if we could think of acetylcholine as appearing and disappearing in a manner entirely different from that involved in its transmission of peripheral parasympathetic effects. We must suppose that an impulse, arriving at the ending of a preganglionic or a voluntary motor nerve fibre, releases with a flashlike suddenness a small charge of acetylcholine, in immediate contact with the ganglion cell or the motor end plate of the muscle fibre. We must suppose that this sudden rise in concentration of acetylcholine stimulates the ganglion cell to the discharge of a postganglionic impulse, or initiates a propagated wave of excitation along the muscle fibre. And we must suppose, further, that the acetylcholine then disappears with a suddenness comparable to that of its liberation, so that it has vanished by the end of the brief refractory period of the ganglion cell or the muscle fibre, which is thus left fully responsive to another discharge of acetylcholine, by another nerve impulse. Such a sequence of events seems to involve two things. The first is a depot, closely related to the preganglionic or motor nerve ending12, in which acetylcholine may be held in some association which prevents its action and protects it from destruction, and from which it can be immediately liberated by the arrival of a nerve impulse. Professor Loewi has mentioned the evidence for such storage of acetylcholine, waiting for liberation, at parasympathetic nerve endings; and Brown and Feldberg13, in my laboratory, have obtained evidence that nearly the whole of the acetylcholine, obtainable by extraction from a normal sympathetic ganglion, disappears when the preganglionic nerve fibres are caused to degenerate by section; so that its maintenance is, in fact, dependent on the integrity of the preganglionic nerve endings. The second thing required, by the suggested action of acetylcholine in transmitting the kind of excitation we are discussing, is a mechanism for its very rapid removal, so that it disappears completely within the few milliseconds of the refractory period of muscle fibre or ganglion cell. One naturally thinks of the specific cholinesterase, first detected by Loewi in heart muscle, and since found to be widely distributed in the blood and tissues. Even when obtained in solution this potent enzyme destroys acetylcholine with a quite remarkable rapidity; and if we could suppose it to be concentrated on surfaces at preganglionic or motor nerve endings, in immediate relation to the site of liberation and action of acetylcholine, it might furnish an adequate mechanism for the complete destruction of this substance, even during the very brief interval of the refractory period. Here, again, I am permitted to make preliminary mention of experiments which Dr. Franz Briicke, who earlier worked under Prof. Loewi, is even now making in my laboratory, and which have already given uniform evidence that a large amount of cholinesterase is present in a sympathetic ganglion, and that this, like the acetylcholine obtainable from such a ganglion, disappears largely when the preganglionic fibres, and their endings in the ganglion, are caused to degenerate. We have evidence, then, that both the reserve of acetylcholine, and the esterase required for its destruction, are in fact associated with the preganglionic nerve endings, as our hypothesis demands. I am departing, however, too far from the true historical order, and presenting recent and confirmatory details of evidence, before I have described the initial observations, which opened this new field to our experimental exploration.

Although from the time when it first became clear that Loewi’s Vagusstoff was acetylcholine, I had begun to consider the possible significance of its “nicotine” actions, it was long before the possibility of its intervention as transmitter at ganglionic synapses, or at voluntary motor nerve endings, seemed to be accessible to investigation. Experiments on the ganglion came first in order. Chang and Gaddum14 had found, confirming an earlier observation by Witanowski, that sympathetic ganglia were rich in acetylcholine. Feldberg, just before he returned to my laboratory for a stay of some years, had observed, with Minz and Tsudzimura15, that the effects of splanchnic nerve stimulation are transmitted to the cells of the suprarenal medulla by the release of acetylcholine in that tissue. Now these medullary cells are morphological analogues of sympathetic ganglion cells, and Feldberg, continuing this study in my laboratory, found that this stimulating _ action of acetylcholine on the suprarenal medulla belonged to the “nicotine, side of its actions. Clearly we had to extend these observations to the ganglion; and a method of perfusing the superior cervical ganglion of the cat, then recently described by Kibjakov16, made the experiment possible. Feldberg and Gaddum17, though unable to reproduce effects obtained by Kibjakow with pure Locke’s solution, found that, when eserine was added to the fluid perfusing the ganglion, stimulation of the preganglionic fibres regularly caused the appearance of acetycholine in the venous effluent. It could be identified by its characteristic instability, and by the fact that its activity matched the same known concentration of acerylcholine in a series of different physiological tests, covering both “muscarine” and “nicotine” actions. It appeared in the venous fluid in relatively high concentrations, so strong, indeed, that reinjection of the fluid into the arterial side of the perfusion caused, on occasion, a direct stimulation of the ganglion cells. It was clear that, if the liberation took place actually at the synapses, the acetylcholine liberated by each preganglionic impulse, in small dose, indeed, but in much higher concentration than that in which it reached the venous effluent, must act as a stimulus to the corresponding ganglion cells. Feldberg and Vartiainen18 then showed that it was, in fact, only the arrival of preganglionic impulses at synapses which caused the acerylcholine to appear. They showed, further, that the ganglion cells might be paralysed by nicotine or curarine, so that they would no longer respond to preganglionic stimulation or to the injection of acetylcholine, but that such treatment did not, in the least, diminish the output of acetylcholine caused by the arrival of preganglionic impulses at the synapses. There was, in this respect, a complete analogy with the paralysing effect of atropine on the action of the heart vagus, which, as Loewi and Navratil had shown many years before, stops the action of acetylcholine on the heart, but does not affect its liberation by the vagus impulses.

My colleagues have added other chapters of interest to this story of chemical transmission at the synapses in the ganglion. I may just mention Brown and Feldberg’s13 observation that potassium ions, the mobilization of which is so intimately connected with the nervous impulse, will liberate acetylcholine from its depot in the ganglion, in a manner closely recalling the effect of preganglionic impulses; and their more recent finding19 that, with prolonged preganglionic stimulation, the ganglion sheds into the fluid perfusing it several times as much acetylcholine as can be obtained from a similar, unstimulated ganglion by artificial extraction. The effects of eserine, on the transmission of excitation in the ganglion, are complicated by a paralyzing action of this alkaloid on the ganglion cells, and still need further elucidation. I can more usefully pass to our recent work on voluntary muscle, in which such effects are much clearer.

The difficulty facing us in the case of the voluntary muscle was largely a quantitative one. In a sympathetic ganglion, the synaptic junctions, at which the acetylcholine is released by the incident preganglionic impulses, form a large part of the small amount of tissue perfused. In a voluntary muscle the bulk of tissue, supplied by a rich network of capillary blood vessels, is relatively enormous in relation to the motor nerve endings, of which only one is present on each muscle fibre. The volume of perfusion fluid necessary to maintain functional activity is, therefore, relatively very large, in relation to the amount of acerylcholine which the scattered motor nerve endings can be expected to yield when impulses reach them. With the skilled and patient co-operation of Dr. Feldberg and Miss Vogt20, however, it was possible to overcome these difficulties, and to demonstrate that, when only the voluntary motor fibres to a muscle are stimulated, to the complete exclusion of the autonomic and sensory components of the mixed nerve, acetylcholine passes into the Locke’s solution, containing a small proportion of eserine, with which the muscle is perfused. If, by calculation, we estimate the amount of acetylcholine thus obtained from the effect of a single motor impulse, arriving at a single nerve ending, the quantity is of the same order as that similarly estimated for a single preganglionic impulse and a single ganglion cell; in both cases 10-15 gram, which corresponds to about three million molecules of acetylcholine. We found that, if the muscle was denervated by degeneration, direct stimulation, though evoking vigorous contractions, produced no trace of acetylcholine. If, on the other hand, the muscle was completely paralysed to the effects of nerve impulses by curarine, stimulation of its motor nerve fibres caused the usual output of acerylcholine, though the muscle remained completely passive. Again there is a complete analogy with Loewi’s observations on the heart vagus and atropine.

With this demonstration, that acetylcholine was liberated at the endings of motor nerve fibres in voluntary muscle, in immediate relation to the motor end plates of the muscle fibres, only one side of our problem had been solved. Acetylcholine, injected into the vessels of a ganglion, could be shown to stimulate the ganglion cells to the discharge of postganglionic impulses. In the case of normal voluntary muscle, on the other hand, the evidence before us suggested only that certain muscles of frogs, reptiles and birds responded to the application of acetylcholine, not by quick, propagated contractions like those evoked by motor nerve impulses, but by slow, persistent contractures, of low tension. As for the normal muscles of mammals, on which our evidence of acetylchohne liberation had been obtained, these were supposed, on evidence provided by myself among others, to give no response at all to acetylchohne, except in large doses, and then only irregularly. The denervated mammalian muscle was known to be highly sensitive to acetylcholine, but the evidence, again from myself among others, suggested that its response was of the nature of a contracture, and not of a quick, propagated contraction.

Considering the manner in which acetylcholine must reach the motor end plates of the muscle fibres, if it were indeed the transmitter of motor nerve excitation – that it must appear with a flash-like suddenness, in high concentration, simultaneously at every nerve ending – we concluded that the ordinary method of injecting acerylcholine, so that it reached the muscle by slow diffusion from the general circulation, could not possibly reproduce this abrupt appearance at the points responsive to its action. We attempted a nearer approach to these supposed conditions of its natural release, by a method which enabled us, after a brief interruption of the arterial blood supply, to inject a small dose of acetylcholine, in a small volume of saline solution, directly and rapidly into the empty blood vessels of the muscle21. The responses which we thus obtained were of an entirely different kind from any which had previously been recorded. A dose of about 2 gamma of acetylcholine, thus injected at close range into the vessels of a cat’s gastrocnemius, produced a contraction with a maximal tension equal to that of the twitch produced by a maximal motor nerve volley, and of a rapidity but little less than that of the motor nerve twitch. We have direct evidence that only a small part of the acetylcholine so injected actually reaches the muscle end plates by diffusion from the vessels; and we argued that, in any case, it could not reach them simultaneously, but only in rapid succession; so that the response, in spite of its superficial resemblance to a rather slow twitch, must actually be a brief, asynchronous tetanus. My colleague, G.L. Brown, using a strictly localized electrical lead from the muscle, involving only a few fibres, has obtained clear evidence that the response has, indeed, that nature. It is a brief burst of unsynchronized and repetitive responses of the individual muscle fibres; but these individual responses are, without doubt, quick, propagated contractions, and there is no semblance of contracture about the phenomenon. Unlike the response of the denervated muscle to acetylcholine, this quick response of normal mammalian muscle is suppressed with great ease by curarine.

At this point I must briefly refer to some observations made only in the past few weeks, and still in progress. The normal mammalian muscle had seemed to present us initially with the greatest difficulty, being supposed not to react to acetylcholine at all. This difficulty being removed by a more adequate technique, we had to face the fact that the function of acetylcholine, as transmitter of voluntary motor nerve impulses, could not be confined to the case of mammalian muscle. The muscle of the frog, the classical object of innumerable studies of neuromuscular conduction, had been found to respond to acetylcholine, indeed, but only by contractures of low tension, and not by propagated contractions comparable to those evoked by nerve-volleys. Here again, we reflected that the method which had been used for the application of acetylcholine, the immersion of the excised muscle in a suitable dilution of the substance, could hardly be expected to reproduce that rapidity of access to the appropriate points on the fibres, which its simultaneous liberation at all nerve endings would achieve. The patient skill of my colleague, G.L. Brown, has now made it possible to apply acetylcholine to the frog’s muscle by direct injection of a small dose into its empty blood vessels, in a manner quite analogous to that which produced such significant results in the mammalian muscle. If 1 gamma of acetylcholine, for example, dissolved in 0.1 cc of Ringer’s solution, is thus injected suddenly into the artery supplying the frog’s gastrocnemius, the surface of the muscle, covered with its glistening aponeurosis, shows immediately the ripple and shimmer of innumerable, unsynchronized contractions, propagated along the fibres and fascicles of the muscle; at the height of the effect a tension of several hundred grams is developed; and the electrical record gives decisive evidence that this response is an irregular, asynchronous tetanus, and not a contracture. With larger doses this tetanus is cut short and extinguished by the contracture – the only effect of acetylcholine on frog’s muscle which earlier work had recognized.

From the study of the mammalian muscle we have also obtained what seems to be clear evidence concerning a mechanism by which acetylcholine, suddenly liberated at the nerve ending to transmit the excitatory effect of a motor impulse to the muscle fibre, may, with a comparable suddenness, be removed completely during the refractory period. If this removal is due, as we have suggested, to the destructive action of cholinesterase, concentrated on surfaces at the nerve ending, we should expect that eserine, with its depressant effect on the action of the cholinesterase, discovered by Loewi and Navratil, would delay the disappearance, from the neighbourhood of the motor end plates of the muscle fibres, of the acetylcholine liberated by a single nerve volley, and would thereby modify the response of the muscle. The effect is easy to demonstrate. Eserine causes, in fact, a great increase of the maximum tension attained by the contraction of the muscle in response to a maximal nerve volley. The all-or-none principle forbade us to suppose that such a potentiated response was a single twitch; and the electrical records showed that it was, indeed, repetitive, and had the nature of a brief, diminishing tetanus21.

The eserine has so depressed the action of the esterase at the nerve endings, that the acetylcholine liberated by a single nerve volley lingers there, and reexcites the muscle at each emergence from successive refractory periods, until the concentration falls at last below the stimulation threshold. Bacq and Brown22 have more recently extended these observations to a series on artificial eserine analogues, and have found that the potentiating action on the response of mammalian muscle to single nerve volleys is, in fact, proportional, in the different compounds of the series, to the anticholinesterase action, as independently determined.

There are many other aspects of these phenomena, some of them still under active investigation in my laboratory. I must be content today to have presented the main headings of the evidence, which, as it seems to me, is forcing upon us the conclusion, in spite of the preconceptions which made the idea initially so difficult to entertain, that acetylcholine does actually intervene as a chemical transmitter of excitation, in the rapid and individualized transmission at ganglionic synapses and at the motor endings in voluntary muscle; that, in the terminology which I have proposed, the preganglionic fibres of the autonomic system, and the motor nerve fibres to voluntary muscle, are also “cholinergic”.

You will see that we are thus led to the conclusion that nearly all the efferent neurones of the whole peripheral nervous system are cholinergic; only the postganglionic fibres of the true sympathetic system are adrenergic, and not even all of these. As I have earlier pointed out, on more than one occasion12, 23, before the evidence for the cholinergic function of voluntary motor nerves was nearly as strong as it has now become, this new classification of nerve fibres, by chemical function, renders at once intelligible the formerly puzzling evidence as to the functional compatibility of different types of nerve fibre, in replacing one another in experimental regeneration. The whole of the evidence of such replacement, obtained by Langley and Anderson early in the present century, can now be summarized by the simple statement that any cholinergic fibres can replace any other cholinergic fibres, and that adrenergic fibres can replace adrenergic fibres, but that no fibre can be functionally replaced by one which employs a different chemical transmitter. The chemical function, as I have expressed it, seems to be characteristic of the neurone, and unchangeable. In that connexion, particular interest appears to me to attach to the recent observations of Wybauw24, which seem to provide clear evidence that the antidromic vasodilatation, generally believed to be produced through peripheral axon branches from sensory fibres, also employs a cholinergic mechanism. If this is substantiated, and if my suggestion holds good that the chemical mechanism is characteristic of the neurone, the question at once presents itself, whether at transmission of excitation will be found.

Hitherto the evidence concerning a chemical transmission in the central nervous system, of the type which we have found prevailing at all peripheral synapses, is scattered and insufficiently uniform in its indications. The basal ganglia of the brain are peculiarly rich in acetylcholine, the presence of which must presumably have some significance; and suggestive effects of eserine and of acetylcholine, injected into the ventricles of the brain, have been described. I take the view, however, that we need a much larger array of well authenticated facts, before we begin to theorize. It is here, especially, that we need to proceed with caution; if the principle of chemical transmission is ultimately to find a further extension to the interneuronal transmission in the brain itself, it is by patient testing of the groundwork of experimental fact, at each new step, that a safe and steady advance will be achieved. The possible importance of such an extension, even for practical medicine and therapeutics, could hardly be overestimated. Hitherto the conception of chemical transmission at nerve endings and neuronal synapses, originating in Loewi’s discovery, and with the extension that the work of my colleagues has been able to give to it, can claim one practical result, in the specific, though alas only short, alleviation of the condition of myasthenia gravis, by eserine and its synthetic analogues.

1. O. Loewi, Pflügers Arch. Ges. Physiol., 189 (1921) 239.

2. O. Loewi, Pflügers Arch. Ges. Physiol., 193 (1921) 201.

3. O. Loewi, Pflügers Arch. Ges. Physiol., 203 (1924) 408.

4. O. Loewi and E. Navratil, Pflügers Arch. Ges. Physiol., 206 (1924) 123.

5. O. Loewi and E. Navratil, Pflügers Arch. Ges. Physiol., 214 (1926) 678.

6. O. Loewi and E. Navratil, Pflügers Arch. Ges. Physiol., 214 (1926) 689.

7. H.H. Dale, J. Pharmacol., 6 (1914) 147.

8. A.J. Ewins, Biochem. J., 8 (1914) 44.

9. R. Hunt and M. Taveau, Brit. Med. J., 2 (1906) 1788.

10. H.H. Dale and H.W. Dudley, J. Physiol., 68 (1929) 97.

11. H.H. Dale, J. Physiol., 80 (1933) 10 P.

12. H.H. Dale, Dixon Memorial Lecture, Proc. Roy. Soc. Med., 28 (1935) (Sect. Therapeutics and Pharmacology, pp. 15-28).

13. G.L. Brown and W. Feldberg, J. Physiol., 86 (1936) 290.

14. H.C. Chang and J.H. Gaddum, J. Physiol., 79 (1933) 255.

15. W. Feldberg, B. Minz, and H. Tsudzimura, J. Physiol., 81 (1934) 286.

16. A.V. Kibjakov, Pflügers Arch. Ges. Physiol., 232 (1933) 432.

17. W. Feldberg and J.H. Gaddum, J. Physiol., 81 (1934) 305.

18. W. Feldberg and A. Vartiainen, J. Physiol., 83 (1934) 103.

19. G.L. Brown and W. Feldberg, J. Physiol., 86 (1936) 40 P.

20. H.H. Dale, W. Feldberg, and M. Vogt, J. Physiol., 86 (1936) 353.

21. G.L. Brown, H.H. Dale, and W. Feldberg, J. Physiol., 87 (1936) 394.

22. Z.M. Bacq and G.L. Brown, J. Physiol., 89 (1937) 45.

23. H.H. Dale, Nothnagel Lecture, No. 4., Vienna: Urban and Schwarzenberg (1935).

24. L. Wybauw, Compt. Rend. Soc. Biol., 123 (1936) 524.

Sir Henry Dale – Banquet speech

Sir Henry Dale’s speech at the Nobel Banquet in Stockholm, December 10, 1936

The whole world admires the fidelity and the wide international vision with which his countrymen have fulfilled the great Trust committed to them by Alfred Nobel, a loyal son of this country and a citizen of the whole world. Among those in all countries who are engaged in the scientific researches which he planned to honour and to encourage, the award of a Nobel Prize stands, without challenge, as the premier distinction to which they can aspire, and the supreme international recognition of their work.

As one of those who, on this occasion, receives this great honour, sincerely distrustful of the claim of my own work to this distinction, I am conscious of a real sympathy with our colleagues here in Stockholm, on account of the anxieties which must weigh upon them, in their great and difficult responsibility of making these awards. I am glad and proud, however, to share the general and grateful conviction, that these decisions are made after an exhaustive examination of claims and a scrupulous weighing of evidence, with no consideration but that of the merits of the work itself.

It seems to me not without significance, that Alfred Nobel defined the field of researches to be recognized by one of his prizes, as that of “Physiology and Medicine”. His aim, in all his plans, was the promotion of human health and happiness; but I think that we are entitled to suppose that, in naming Physiology with it, showed a conviction that the practical and beneficent science of Medicine, with its direct concern for the preservation of health and the healing of disease, grows and flourishes only with a steady cultivation of those experimental sciences in which it is rooted and from which it draws its nourishment. We may surely trace in this conjunction a design to encourage and to reward those who till the soil and sow the seed of exact science, together with those who have the added joy of reaping the harvest of life-saving knowledge. Here, again, I am confident that world opinion acclaims the steady hand, with which the Nobel Committee of the Caroline Institute, in discharging their Trust, have held the balance justly between these related and complementary aspects of the Founder’s intention. In recent years we have seen them give due honour to fundamental researches over a wide range of subjects in physiology, biochemistry and pathology, and we have seen them honour, with no less justice, discoveries which have found immediate use in the treatment of diseases. This year, by what comes to me as a marvellous stroke of fortune, their choice has fallen on researches belonging, perhaps, to the borderland between physiology and pharmacology. Let me say that my pride and pleasure in this award is greatly enhanced by the fact that I share it with my old and intimate friend, Professor Loewi. Otto Loewi and I first met as young men, some 35 years ago, in the London laboratory then and for many years afterwards known to all the world by the work of Bayliss and Starling. Loewi then worked for a further short period in the Cambridge laboratory of my earlier teacher, J. N. Langley; so that I feel that to some extent we inherited a common tradition, from great men of the generation of our teachers. We met again when I went for a time to the Institute of Paul Ehrlich in Frankfurt, Loewi being then in Marburg with Hans Horst Meyer, who still sustains his weight of honoured years. In the years that have intervened, though our lives and our work have been widely separated on the map of Europe, and though for tragic years all contact between us was prevented by the disastrous clash of national enmities, we have retained unbroken a scientific and personal friendship, which is now strengthened and sealed by the honour in which I am proud to be associated with him. Though our work has been done independently, the natural lines of its development have more than once converged. The work in which my colleagues and I have been engaged in the past few years, and which has brought to me this great recognition, is largely a development from Loewi’s discoveries of 10 to 15 years ago. We have both, I believe, followed this line of enquiry for the simple physiological interest of the new principle which Loewi’s experiments first clearly established, and to which our own have given a wider application; but I feel a confidence, which I expect that Professor Loewi shares, that this principle, with its widening scope, will yet have an influence and an application in the understanding and the scientific treatment of disease. There are signs of this already, but I believe that the future will show it in such measure as to justify the faith in which Alfred Nobel linked Physiology and Medicine.

I thank you again for this magnificent reception, for the great honour which I have received, and for your generous and gracious hospitality.