Walter Hess – Other resources

On Walter Hess from Universität Zürich

Walter Hess – Photo gallery

1 (of 2) 1936 Nobel Prize Award ceremony, 10 December 1936. From left: Medicine laureates Otto Loewi and Sir Henry Dale, chemistry laureate Peter Debye, physics laureates Carl David Anderson and Victor F. Hess.

Source: Wellcome Collection. CC BY 4.0 , via Wikimedia Commons

2 (of 2) Professor Walter Rudolf Hess with his wife arrives to Bromma Airport, Sweden, for the Nobel Week, 6 December 1949.

Photo: SAS Scandinavian Airlines. Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Walter Hess – Banquet speech

Walter Hess’ speech at the Nobel Banquet in Stockholm, December 10, 1949 (in German)

Wenn ich so sprechen wollte, wie es mir jetzt ums Herz ist, so käme ich in einige Verlegenheit; denn die Gefühle, die mich bewegen, sind von so ursprünglicher Kraft und Freude, wie man sie eigentlich nur in den Jugendjahren zu erleben vermag. Es müsste mir also gestattet sein, mich in unserem ostschweizerischen Idiom auszudrücken. Ich fürchte aber, dass ich dann nur von allzu Wenigen verstanden würde. So benütze ich die bei uns gebräuchliche Schriftsprache, um – soviel es mich angeht – dem grossen Stifter Alfred Nobel und auch allen jenen zu danken, welche dieses Fest so schön und inhaltsvoll gestaltet haben.

Im Rahmen der Feier ist ein Funken gesprungen, welcher die Beziehungen Schweden-Schweiz in einer, für mich sehr sympathischen Weise beleuchtet. Daneben gibt es aber auch Beziehungen rein ideeller Natur. Es ist kaum ein halbes Jahr her, als ich durch einen in schwedisch Lappland gepflückten Blumenstrauss daran erinnert wurde. Die Blumen waren nämlich derselben Art, wie wir sie bei uns in den Alpen in Gletscher Nähe finden. Mit dem Zurückgehen der letzten Eiszeit sind sie bei uns in die Hochalpen, bei Ihnen in den hohen Norden gewandert. Heute durch weite Landstriche getrennt, bezeugen sie aber immer noch in ihrer Form und Farbe, dass sie Brüder sind, als welche sie das nordische Schweden mit der alpinen Schweiz durch die Sprache der Flora verbinden.

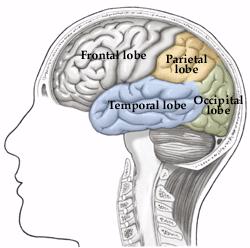

Prior to the speech, Carl Skottsberg, President of the Royal Academy of Sciences, addressed the laureate: “Walther Hess, your field is the human brain, and if it is true that man is the crown of creation – which, however, has still to be proved – and that the human brain is the most perfect organ Nature ever invented, which seems likely, no more exquisite object for your genius could be found. With the help of the most ingenious experiments you made fundamental discoveries with regard to the functions of the brain, and the proofs you have furnished of the existence of coordinating centres have roused the greatest attention all through the medical world.”

Egas Moniz – Banquet speech

As the Laureate was unable to be present at the Nobel Banquet at the Swedish Academy in Stockholm, December 10, 1949, the speech was held by Mr. Patricio, chargé d’affaires of the Legation of Portugal (in French)

Altesses Royales,

Excellences, Mesdames, Messieurs,

J’ai l’honneur d’adresser au Collège des Professeurs de l’Institut Carolin les remerciements les plus vifs, les plus chaleureux et les plus émus, pour l’honneur qu’il vient de faire à mon éminent compatriote le Professeur Egas Moniz, en lui décernant le prix Nobel de médecine. Si l’illustre savant portugais eût pu être présent à cette magnifique fête suédoise, il vous aurait, certes, signifié sa gratitude, d’une façon bien plus éloquente et en des termes d’une substance bien plus profonde. Cependant, malgré le caractère essentiellement personnel de la haute distinction dont il fut l’objet, je suis heureux de pouvoir exprimer au Collège des Professeurs, non seulement la reconnaissance du lauréat lui-même, mais celle de toute la science portugaise, ainsi que la joie que mon pays a ressentie, en apprenant la bonne nouvelle.

Comme représentant officiel du Portugal, j’oserai vous dire que j’en suis modestement fier, s’il m’est permis d’employer cette expression d’apparence contradictoire.

Il est bien connu de tous que le prix Nobel signifie la reconnaissance internationale de la valeur intellectuelle de l’individu, et nous qui sommes un peuple ayant accompli le long de l’Histoire des choses fort importantes avec un matériel humain extrêmement réduit, nous attachons une valeur immense à toute marque d’admiration pour les exploits de l’âme et de l’esprit.

L’intelligence et la puissance créatrice sont toujours des dons merveilleux, mais lorsque s’y joignent l’esprit de sacrifice et le dévouement désintéressé au bonheur humain, leur beauté supérieure resplendit d’une lumière divine.

Les hommes de science, les savants, notamment, de la science médicale, savent que la vérité est fuyante et le bonheur absolu inaccessible, mais ils replient et tendent les ailes de leur pensée, dans l’effort d’atténuer les souffrances humaines. Dans le chaos des misères et des chagrins, ils passent comme une lueur d’espoir, tenaces, anxieux et persévérants. Pour eux, pour leur esprit positif, le régime général de la nature est réglé par un ordre inflexible et aucune prière ne saurait le modifier. Seule, la perspicacité de leur intelligence peut dérober à Dieu quelques vérités partielles. ‘They look upon the mistery of things as if they were God’s spies.’

Nous autres qui venons en Suède, nous y apprenons la leçon incomparable de l’intelligence calme et scientifique, de son application systématique à l’amélioration des conditions de la vie sociale et au perfectionnement de la beauté de l’âme et au perfectionnement de la beauté du corps. Dans l’harmonie des lignes et des attitudes, dans la grâce rythmique des gestes et dans l’équilibre des pensées, on dirait reconnaître le dieu de Délos, passant dans son char, joyeux et plein de promesses, à travers les forêts riantes de la Dalécarlie ou sur les lacs glacés et poétiques du Vermland. Bienheureux et noble peuple de Suède, je lui souhaite de toujours vivre sous le triple signe de la beauté, de l’intelligence et de la sérénité.”

Prior to the speech, Carl Skottsberg, President of the Royal Academy of Sciences, addressed the laureate: “There is, I believe, some connection between the work of professor Hess and that of Professor Antonio Egas Moniz, who share the prize in medicine, though it isn’t in any way a case of mutual or any other kind of influence. Professor Moniz was a notorious savant in various fields when, accidentally, he came to the conclusion that the surgeon’s knife would bring relief or even recovery to patients suffering from certain serious psychic disturbances. Boldly he went to work. He was 61 when he made his first brain operation for this purpose. Today his method is practised everywhere with very good results. We regret that he has been unable to come, for we would have loved to meet this wonderful man, a famous scientist, a writer of historical books, a politician, statesman and diplomat, all in one person, and the more so as he is the first Portuguese whose career is crowned with a Nobel prize. I shall ask the official representative of Portugal kindly to congratulate Professor Moniz on our behalf and to express to him our gratitude and admiration.”

Egas Moniz – Nobel Lecture

No Lecture was delivered by Professor E. Moniz.

Walter Hess – Nobel Lecture

Nobel Lecture, December 12, 1949

The Central Control of the Activity of Internal Organs

A recognized fact which goes back to the earliest times is that every living organism is not the sum of a multitude of unitary processes, but is, by virtue of interrelationships and of higher and lower levels of control, an unbroken unity. When research, in the efforts of bringing understanding, as a rule examines isolated processes and studies them, these must of necessity be removed from their context. In general, viewed biologically, this experimental separation involves a sacrifice. In fact, quantitative findings of any material and energy changes preserve their full context only through their being seen and understood as parts of a natural order. This implies that the laws governing organic cohesion, the organization leading from the part to the whole, represent a biological uncertainty, indeed an uncertainty of the first order. It becomes all the more acute, the more rapidly the advances of specialization develop and threaten the ability to grasp, or even to appreciate it. While this state of affairs has just been referred to, our subject is defined by its general content. In particular it deals with the neural mechanisms by which the activity of the internal organs is adapted to constantly changing conditions, and by which they are adjusted to one another, in the sense of interrelated systems of functions. It only remains to be added that broadening of our knowledge in these respects is of benefit not only with regard to the human compulsion to understand, but also to the practical healing art. For man also, in health and sickness, is not just the sum of his organs, but is indeed a human organism.

After this short introduction, we now come on to the concrete complex of questions, to which has been devoted the work whose results have earned me this great distinction and have thus brought me into this high circle. The initial situation is defined by the findings, which have now been turned to the common good, concerning the morphological and physical structure of the so-called vegetative – “autonomic” in English usage – nervous system. This was – I believe – a good start, and was brought about by the achievements of the great masters W.H. Gaskell and J.N. Langley, and had been given shape in an easily comprehensible and stimulatingly graphic exposition by the distinguished pharmacologists H.H. Meyer and R. Gottlieb. Of particular interest here in this conception, for which there is good experimental confirmation, is the paired antagonistic innervation of the internal organs, and their grouping according to the separate regions in which the peripheral organization is linked to the central nervous system. (The keywords sympathetic and parasympathetic characterize the relationships under consideration.) In contrast to the exploration of the vegetative nervous system, which is very far-reaching (even if it is not still without certain inner contradictions) stands a relatively limited understanding of the central organization of the whole mechanism of control. This is not easily understood, because the informative experiments must explore a segment in which elements are also assembled and integrated, which subserve special sensory functions and the movement of the body. Things that are distributed over a wide area in the body itself, lie close together in the central nervous system. Correspondingly an unequivocal differentiation is disproportionately more difficult. The direct contiguity of functionally multivalent pathways and nuclei confuses the experimental elucidation of related symptoms. One thing had nevertheless become clear, namely that the parts of the brain communicating directly with the spinal cord at the upper end – the medulla oblongata, and the segment lying directly beneath the cerebrum, the so-called diencephalon – exert a decisive influence on the vegetative controlling mechanisms. As regards the diencephalon further orientation had been achieved to the extent that it was realized that the parts of it lying nearest the base of the skull, i.e. the hypothalamus, were particularly important to the nature of the whole enquiry. Observations at the sickbed in conjunction with what was ascertained in the deceased at autopsy, and in addition experiments which provided some rough pointers, had led to this insight (Karplus and Kreidl et al.). Something which still, however, lay in obscurity, when my own investigations were started, was the allocation of definite functions to particular morphological substrata, was, in other words, the organic structure of the diencephalic vegetative control system. To throw as much light as possible on this was the task which I set myself.

At the beginning of all experimental work stands the choice of the appropriate technique of investigation. In many cases it has first to be created; it was so here as well. Although the method used to produce the results was of decisive importance, it can only be gone into in outline here. In the first place, satisfaction of two requirements was decisive, these two being a condition of the special circumstances in the central nervous system, which have been described: one concerns the technical devices, which were taken practically to the limits of refinement; the other is related to securing the minimum obstruction to the experimental animal’s modes of expression. We would like to emphasize these two, because in these particulars American investigators, whose merit is beyond doubt (especially Ranson and Magoun), have followed another path, beset with various avoidable experimental errors. But, here as there, fundamental to the investigations lay the same principle which enables to obtain information, if one wishes to explore the layers and connections which lie below a surface: one applies “probes”. In our case, artificial foci of excitation were produced with electrical impulses, and their effects noted. In addition, the technique of localized exclusion was also applied; as with disease foci, the reactions of this on the behaviour were interpreted in terms of disappearance of symptoms and were linked indirectly to the functional significance of the excluded substrata.

If I had thought, by observing the effects of artificial electrical stimuli in small doses on some dozen or so experimental animals with altogether some hundred points of stimulation distributed over the diencephalon, to achieve in due course the looked-for elucidation, then the first result was a thorough disappointment. The only positive finding which could be drawn from the first series, was the conclusion that the relationships obviously had a more complicated lay-out than had been thought, for the effects were so varied that no obedience to any law could be discovered. To meet this situation, the experiments had to be carried out on a considerably expanded basis. This was a simple enough conclusion; its realization was a different matter. It must be born in mind that one does not see directly – as is the case in the exploration of the surface of the brain – where the electrodes are attacking. Exact information about the functional significance of the deep sections of the brain is only obtained by working through the brain histologically in serial section. To avoid far too great delays, the experiments must be fitted in together as it were in time, and it is only possible to keep the material collected under control by using a carefully organized system of registration. The difficulty of finding one’s way around in the abundance of individual observations was overcome by a graphic method. The extension of the experiments on the widest basis means time. To this is added the expenditure – for Swiss circumstances – of considerable funds. I make these last references on the one hand to make the slow growth of knowledge comprehensible, and on the other to be able to thank the various Swiss Foundations and above all the Rockefeller Foundation of New York for their financial support.

This short outline of the method of working brings us to the question of the results. As we go into these, certain motor effects, although they merit great interest, must be left on one side.

Now, concerning the influence of the diencephalon on the activity of the internal organs, the following facts could be disclosed: first of all, it has turned out that the functions which are mediated by the sympathetic section of the vegetative nervous system, are related to the posterior and middle parts of the deepest section of the hindbrain, i.e. of the hypothalamus. So the latter is to be considered, as it were, as the central area of origin of the sympathetic system. In order to give this discovery its full physiological import, some more elucidation is required. The goal of physiological research is functional nature. So in the course of this preoccupation with the vegetative nervous system, among other things the question has arisen of whether a circumscribed role is associated with the classical sympathetic system, which is defined primarily in terms of its area of origin, which is restricted to the thoracic spinal cord. An investigation undertaken from the viewpoint of the effect of its activity has yielded the finding that this is the case to a considerable extent. Where the sympathetic intervenes, it assists the body’s efficiency and it aids the organism to greater success in its conflicts with its environment. It is functional, in so far as it behaves like an ergotropic or dynamogenic system. In addition to this item of knowledge there are still more findings which will interest the psychiatrist in particular, but also everyone who realizes that behind the variety of types of phenomenon stands the unity of the organism. On stimulation within a circumscribed area of the ergotropic (dynamogenic) zone, there regularly occurs namely a manifest change in mood. Even a formerly good-natured cat turns bad-tempered; it starts to spit and, when approached, launches a well-aimed attack. As the pupils simultaneously dilate widely and the hair bristles, a picture develops such as is shown by the cat if a dog attacks it while it cannot escape. The dilation of the pupils and the bristling hairs are easily comprehensible as a sympathetic effect; but the same cannot be made to hold good for the alteration in psychological behaviour. For this, only connections between hypothalamus, thalamus and cerebral cortex come into consideration. Functionally, the total behaviour of the animal illustrates the fact that, in the part of the diencephalon indicated, a meaningful association of physiological processes takes place, which is related on the one hand to the regulation of the internal organs, and on the other involves the functions directed outwards towards the environment. In other words: we know the key position in the diencephalon which has one aspect directed inwards and one aspect directed outwards. The sympathetic system is thereby, within the framework of a far-reaching organization, the mediating agent which intervenes particularly in the activity of the internal (vegetative) organs. With regard to the manifest influence of the psychomotor system and the psychological processes of association, a bridge is thrown over a gap, still wide open today, which lies between the purely somatically oriented physiology and psycho-physiology. It completes and broadens the insight into psychosomatic relationships, in the way they had been demonstrated by the great Russian physiologist Pavlov, who approached them from another side. To him also fell the great honour of speaking from this position.

In spite of the necessary restrictions on our exposition, observations of a different kind will induce us briefly to touch on the theme of somato-motor phenomena once again. Before this, another striking finding must be reported. The individual, vegetatively innervated, organ gets its differentiated innervation in the known peripheral organization of the sympathetic ergotropic system; correspondingly it can also be brought into action in isolation. This fact and the relationships, as they are met with, for example in the projection of the peripheral organs reacting to nervous stimulation in the motor area of the cerebral cortex, could give grounds for supposing that the individual internal organs also have a discrete representation in the diencephalon. In such an order of things the ergotropic zone would also be organized as it were by organs. The experimental findings offer proof that in reality the relationships are disposed differently. The fact is that even the most narrowly circumscribed forms of excitation and the most delicate stimulus dose never bring to light an isolated symptom related to one organ. In every case a group symptomatology makes its appearance. It is always groups of organs that are called into action, and indeed in such a way that the individual effects are combined, namely in accordance with the principle of synergistic coordination. Controls issue from the diencephalon which harness the functional capacities of individual organs in viable responses. This order of things holds good quite markedly in the ergotropic zone.

But under the influence of circumscribed stimuli applied to the hypothalamus, and partly also to the layers of the thalamus lying close above it, symptoms have also appeared which do not permit of classification in the sympathetic-ergotropic system of functions, and indeed rather act in opposition to this. The blood pressure, for example, does not respond by a rise, but by a fall; the heart rate does not increase, but rather decreases. At the same time respiration slows down, as opposed to the speeding-up which is obtained from the ergotropic-dynamogenic zone. Often a profuse flow of saliva occurs; further symptoms are choking and vomiting, micturition, defaecation. In other cases panting is caused, i.e. the mechanism most often seen in the dog under natural conditions, when it is hot. While the tongue, with its rich blood supply, moistened by a copious flow of saliva, hangs out of the wide-open mouth with the flow of air due to rapid respiration streaming over it, the discharge of excess heat takes place. This function, which is also common to the cat, serves the regulation of temperature and is in this sense equivalent to sweating (e.g. in man) when heat accumulates. Another effect of stimulation not mentioned so far is constriction of the pupils, followed by a drawing-across of the nictitating membrane.

To summarize, we are dealing with symptoms which are characteristic of a decrease in the influence due to the sympathetic system, and of an increase of parasympathetically transmitted excitation. Regarding the physiological effect, such reactions bring functional relaxation to the individual organs, or protection against overloading, but indeed protection above all. Where the digestive processes are concerned, the complex serving restoration is mediated by separate mechanisms. Since we give these related effects a common denominator in their functional aspect, the term “trophotropic system” is appropriate. Moreover the experimental findings show that a circumscribed region of the diencephalon corresponds to it, namely the anterior part of the hypothalamus, the area praeoptica, and the septum pellucidum as well. With this, a central, fairly clearly demonstrable division of the two partners of the vegetative nervous system becomes manifest. This is all the more noteworthy, as they are most intimately interwoven in their peripheral terminal territories. Important, too, is the establishment that there is no evidence in the trophotropic zone of a central organization corresponding to particular organs. It emerges conclusively from the effects obtained from the most varied sites of stimulation falling in the area named that here too no grouping is found in contrast, for example in the formation of nuclei; each particular syndrome shows a fairly large scatter. This does not, however, conceal the fact that some effects are preferentially released from certain larger areas. It is different in this respect from the ergotropic zone, where the group organization is more consistent.

We take a step forward, when we turn our attention to the observations from which it emerges that reciprocal mutual connections operate between the sympathetic-ergotropic and the parasympathetic-trophotropic areas, indeed in the sense that at each moment they produce a dynamic equilibrium adapted to the situation at any given moment of the organism as a whole. In this equilibrium the unity of the central regulation of the whole vegetative system is expressed. In the broad view, competition is a constructive principle!

With this statement, we could conclude our exposition, that is, if we wanted to confine it to a more narrowly conceived theme. But among the fundamental results of the experimental exploration of the diencephalons alone was the finding that the effects produced from this part of the brain are not restricted to the vegetative system. Indeed the rule is that they are associated with somatomotor symptoms. When I refer to this, I do not have in mind the functions which testify to a higher order regulation of bodily posture within the framework of the extra-pyramidal motor system. What we are discussing here concerns the motor symptomatology which stands in a specific relationship to the vegetative function. This is where our interest lies, if we attend briefly to this state of affairs. So let us look at a new stage in the integration of the organ functions in the total performance. In this way, for example, we can understand the experimental finding, that in many cases where the stimulus applied to the diencephalon causes defaecation, this is not brought about simply by peristalsis of the colon and rectum. In particular, where a stimulus is applied to the most rostrally situated regions, the cat adopts the normal posture for the physiological deposition of faeces; therefore the stimulus activates the skeletal musculature, which is innervated by the cerebrospinal axis, and which is also responsible for the abdominal muscular pressure. It was possible to make the same observation during micturition. The synergistic coordination between the function released through the vegetative nervous system and the somatomotor complement is manifest. An improvement in the result is obtained, partly in the form of a speeding-up of the process, and partly in the way soiling is avoided.

Particularly impressive is the synergistic coordination of mechanisms controlled by the vegetative nervous system with cerebrospinal innervated activities in the defence mechanism which is accompanied by emotion. This had already been the subject of discussion, but without any particular light being thrown on the structure of the action as a whole in relation to the systematic involvement of somatomotor phenomena. Dilation of the pupils, bristling of the hair are the vegetative components, and snuffling and spitting as somatomotor processes complete the picture intended to scare off the opponent. The aimed blow with the paw conclusively presupposes a visual orientation, which, while compulsive in affect, nevertheless fits in adaptively because of the intervention of the cortex. Thus one sees how the various levels make their contribution to the full success of a complete activity, and one understands how individual functions are associated in stages in an activity carried out by the organism as a whole.

According to this view of how the diencephalon plays a decisive role in activity which progresses from the part to the whole, it will come as no surprise if still other observations could be made which lead in another direction. Thus it has been seen that under defined experimental conditions a constriction of the pupil and a drawing-across of the nictitating membrane may be caused from a certain region of the diencephalon. A slowly developing narrowing of the palpebral fissure accompanies these events, which reflect a decrease in the sympathetic innervation, which – particularly in the pupil – occurs with an increase in parasympathetic influence. These effects also are not infrequently associated with certain symptoms under the nervous control of the central nervous system: the drooping of the upper eyelid develops into an active closing of the lid. Simultaneously the head droops, whereupon, as the syndrome develops further, the whole animal lies down. It is necessary to observe this process accurately in its development and in the final stage; it will be noticed, as you will realize, that the cat does not simply collapse, as is the case with generalized loss of tone. Under the influence of gradual relaxation the animal choses its place and curls up. Altogether a picture results like that known under physiological conditions only in the sleeping cat. In a certain sense one is presented with the mirror-image of the emotionally aroused cat with increased excitability; for the readiness to react to sensory stimuli is markedly decreased, whereby – as in the normal sleeping cat – the tickle reflex of the ear stays “awake”. Behaviour towards olfactory stimuli is also relatively little inhibited, which are effective as a more potent arousal stimulus, thereby proving the reversibility of the whole process. In other respects, as has been mentioned, the preparedness for energetic activity is reduced to a minimum. Clearly, in the competition between ergotropic and trophotropic systems the former forfeits some of its influence on the organism as a whole in favour of an excess of the latter. But it must always be borne in mind that we are dealing with the result of artificial stimulation, and indeed in a limited area. To explain the gradual development of this inhibition of activity as the result of destruction in the hypothalamus is misleading. On the other hand it is correct that one is dealing with a protective function controlled from the diencephalon, which avoids exhaustion and produces the conditions for an undisturbed recovery. The latter – judging by the physiological sleep – particularly concerns the higher centres. For the rest, as regards the where and the why, electroencephalography, e.g. in the line of research by Jasper, and biochemistry have the say in the matter now. So the investigations, which have been reported here, have, as is the rule, in addition to a clear understanding also brought into focus the formulation of new questions.

Now that we have come full cycle with the investigation in which the integrating activity of the diencephalon was experimentally differentiated, I would very much like to show some more pictures, with which the spoken word will be clarified. The time available, of course, permits only a limited selection of slides and a film. But I think they are enough to provide an objective representation of what has been said.

1. The following were shown, as lantern slides: rise in blood pressure, fall in blood pressure, increase of respiration, slowing of respiration; in the film: methodology – dilation of pupils, retraction of the nictitating membrane, defaecation, retching, panting – licking movements, chewing movements, sniffing movements – affective reactions: spitting, bristling of hair, leaping to attack, urge to eat, urge to flee – atonia as an effect of stimulation – adynamia as an effect of exclusion – sleep as the effect of stimulation.

2. The following localizing findings were presented: medium section of the cat’s brain and further sagittal sections with symbols marked in (lowering blood pressure, raising blood pressure, pupil dilation, pupil constriction, affective defence, hunger drive).

Egas Moniz – Nominations

Walter Hess – Nominations

Controversial Psychosurgery Resulted in a Nobel Prize

Controversial Psychosurgery Resulted in a Nobel Prize

by Bengt Jansson*

This article was published on 29 October 1998.

Summary

In 1936, the Portuguese neurologist Egas Moniz introduced a surgical operation, prefrontal leukotomy, which after an initial period came to be used particularly in the treatment of schizophrenia. The operation, later called lobotomy, consisted in incisions that destroyed connections between the prefrontal region and other parts of the brain.

At that time there did not exist any effective treatment whatsoever for schizophrenia, and the leukotomy managed at least to make life more endurable for the patients and their surroundings. The treatment became rather popular in many countries all over the world and Moniz received the Nobel Prize in 1949.

However, by this time the treatment had had its most successful period and in 1952 the first drug with a definite effect on schizophrenia was introduced, chlorpromazine, our first neuroleptic drug. Since about 1960 lobotomy, with a strongly modified technique (more discrete incisions), has been used only when there are very special indications such as in severe anxiety, and compulsive syndromes which have proved to be resistant to other forms of therapy. Perhaps about five operations a year are now being performed in Sweden.

However, I see no reason for indignation at what was done in the 1940s as at that time there were no other alternatives!

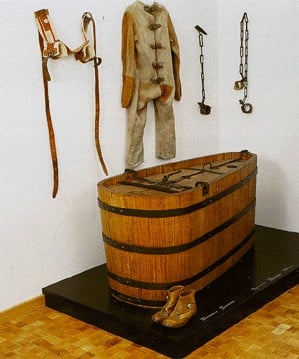

Chains, straitjacket, cell belt and covered bath tub (72 x 150 x 69 cm) for restraining raving patients, Burghölzli Hospital, Zurich.

Therapeutic Alternatives for Psychotic Patients Before the 1930s

As a rule therapeutic methods developed considerably later in psychiatry than in other medical fields. Violent patients, dangerous to their surroundings, sometimes had to be restrained or immersed in baths for long periods. Another alternative was heavy sedation with opiate derivatives or barbiturates. However, none of these treatments had long-term effects on psychotic patients.

It was not until the 1930s that Manfred Sakel in Vienna introduced hypoglycaemic coma, produced by injections of insulin, as a treatment for schizophrenia. At the same time the Hungarian Ladislav von Meduna started seizure therapy by intravenous injection of cardiazol (in depressive states), a therapy that was abandoned when in 1938 the Italians Cerletti and Bini introduced electric convulsive therapy, E.C.T., for severe mental states. This treatment was first used in schizophrenia, but severe depressive states very soon proved to be the main indication. Tranquilizers with more than a very short-lived sedative effect did not exist until 1952 when the Frenchmen Delay and Deniker introduced our first neuroleptic drug, the phenothiazine derivative chlorpromazine.

Introduction of Prefrontal Leukotomy*

Cerebral surgery had been tried in a few psychiatric cases as early as 1891 and 1910, particularly patients with manic-depressive psychosis. These trials did not attract much attention, but at a neurology conference in London in 1935, at which the Portuguese neurologist Egas Moniz participated, Jacobsen & Fulton presented data from operations on two chimpanzees which, after a leukotomy, managed to make mistakes without becoming aggressive, something which they had not managed to do before. Many people have considered this information to have instigated Moniz’s “bold step” in November 1935. In 1936 Moniz published his first report on prefrontal leukotomy.

One reason why Moniz’s operations gained better acceptance than the earlier trials mentioned above was evidently the fact that he was internationally respected for having developed cerebral angiography. Moniz’s first twenty cases all survived and did not develop any serious morbidity. The leukotomy soon achieved a good reputation in, among other countries, Brazil, Italy and the United States. Moniz strongly believed that the potential benefits of surgical lesions in the frontal lobes, even allowing for some behavioral and personality deterioration, outweighed the debilitating effects of severe psychiatric illness.

Leucotome.

Refined Surgical Techniques

Moniz, working together with the neurosurgeon Almeida Lima, first injected alcohol as a sclerosing agent into the white matter of the frontal lobes. Moniz soon refined his technique by designing a “leucotome,” an instrument with a retractable wire loop and later replaced with a steel band, which he used to cut six cores in the white matter of each hemisphere. For twenty patients in a first series, and eighteen in a second, the results were considered rather acceptable by Moniz in 1937, although he concluded that deteriorated patients did not benefit much from the operation. Of the 18 patients in the second group (all schizophrenic), three were characterized as almost cured and another two also had become much better. Moniz’s conclusion was this: “Prefrontal leukotomy is a simple operation, always safe, which may prove to be an effective surgical treatment in certain cases of mental disorder.”

The blue spots indicate the areas operated on.

Among those who followed Moniz’s lead, none was more prominent than the neurologist and neurosurgeon team of Walter Freeman and James Watts in the United States. Freeman and Watts first used Moniz’s leucotome technique, but they soon developed a procedure designed to more completely ablate the white matter tracts to and from the prefrontal lobes. Freeman and Watts performed about 600 operations with this “closed procedure,” which became known as the standard prefrontal lobotomy of Freeman and Watts. The first “open operation” was performed by Lyerly in 1937 who, using a superior approach to each frontal lobe with the aid of a specially lit speculum, attempted to separate the white fibers under direct vision. This method became the standard procedure in the United States as the open method was considered to reduce the main complication of psychosurgery, haemorrhage of the anterior cerebral artery.

Side Effects on Personality

Negative effects on personality were observed as early as the end of the 1930s. In 1948, Swedish professor of forensic psychiatry Gösta Rylander, reported a mother as saying: “She is my daughter but yet a different person. She is with me in body but her soul is in some way lost.” Hoffman (1949) writes: “these patients are not only no longer distressed by their mental conflicts but also seem to have little capacity for any emotional experiences – pleasurable or otherwise. They are described by the nurses and the doctors, over and over, as dull, apathetic, listless, without drive or initiative, flat, lethargic, placid and unconcerned, childlike, docile, needing pushing, passive, lacking in spontaneity, without aim or purpose, preoccupied and dependent.”

Who Were Operated On?

Initially operations were performed on a majority of patients with affective disorders, i.e. various types of depression, such as involutional depression, agitated depression and so on. Very few psychiatrists remember this because E.C.T. (electric convulsive therapy) had already been introduced in 1938 and quickly proved to be a very effective treatment for depressive states. Other groups of patients were those with severe obsessive-compulsive and hypochondriac states. As a rule, severity was a more important factor than diagnosis, i.e. consideration was taken to suicidality and dangerousness, among other things.

A few patients suffering from schizophrenia were operated on at the end of the 1930s, but neither Moniz’s original seven patients nor any of those 12 schizophrenic patients from Freeman & Watts´ first 80 cases showed any marked improvement. Freeman based his opinion quite early on that if schizophrenic patients are to be operated, it should be done early before they have become apathetic or have deteriorated, because such patients “behaved the same with or without their frontal lobes” (Swayze 1995). This opinion became more and more dominant (Kalinowsky & Scarff, 1948). In other words the first year of illness should be used to try all the other somatic therapies. At a conference in 1953, it was shown that mortality varied between 0.8% and 2.5%. At the same time, approximately 10% of operated patients were known to have some problems with epilepsy.

Why Was Psychosurgery so Popular in the 1940s?

Swayze (1995), whose paper is strongly recommended for reading (see reference), mentions some important contributory factors. First, there were no alternative therapies available for chronically institutionalized patients. Second, during and following World War II there was an alarming increase in the number of admissions to psychiatric institutions in the United States. For example, there were 100,000 new admissions to mental institutions and only 67,000 discharges in 1943, and in 1946 nearly one-half of the public hospital beds were devoted to the mentally ill (Menninger 1948). Third, prior to 1930, patients continuously hospitalized for 15 years with a diagnosis of manic-depression had a 18% mortality rate due to tuberculosis and other infectious diseases. Thus, the importance of discharging patients from the state institutions was apparent. Another factor, according to many doctors, was that a long stay in a mental institution in itself contributed to the fact that many patients became apathetic.

Were the Patients Cured?

A survey of all patients who underwent leukotomy in England and Wales from 1942 to 1954 (Tooth et al 1961) documented 10,365 single leukotomy operations. An additional 762 patients underwent more than one operation. A follow-up study covering 9,284 of the above mentioned patients showed that 41% had recovered or were greatly improved while 28% were minimally improved, 25% showed no change, 2% had become worse and 4% had died. Not surprisingly, patients with an affective disorder showed the best prognosis with 63% recovered compared to 30% among schizophrenic patients.

In the United States approximately 10,000 operations had been performed by August 1949. After 1954 the number of operations steadily decreased. As there were no alternative therapies for severe mental disorders, psychoses in the 1930s, it is not surprising that lobotomy was quickly accepted as a therapy for chronic schizophrenic psychoses, even if it seems a bit strange that lobotomy initially was tried with affective disorders. Lobotomy is an ethically dubious treatment if carried out against the patient´s wishes, but this is always a difficult question in severely psychotic patients who totally lack insight about their illness – what is it exactly that such a patient wants? Historically, it is easy to understand that psychosurgery was considered as a therapeutic advance. Today, it is easy to hold a negative opinion about the use of lobotomy and consider it very strange that Moniz was awarded the Nobel Prize. However, I agree with Swayze (1995) who has written: “If we learn nothing else from that era, it should be recognized that more rigorous, prospective long-term studies of psychiatric outcome are essential to assess the long-term outcomes of our treatment methods.”

Development of Alternative Methods

The development of neuroleptics, which started with chlorpromazine in 1952, very soon made lobotomy uninteresting in the treatment of schizophrenia, and the number of lobotomies in schizophrenia dropped dramatically after about 1960. During the 1970s a refined computed tomography-based stereotactic technique was developed making it possible to make selective lesions of specific fiber systems. The main target area is the limbic system which is closely related to emotions. The most important procedure is bilateral anterior capsulotomy (in the United States also cingulotomy), and the indications have changed to chronic anxiety – and obsessive compulsive syndromes which have shown themselves resistant to other treatments. Anxiety disappears first, but the obsessive symptoms gradually also diminish when they are not maintained by anxiety. In Sweden we perform about 5 such operations a year.

Chlorpromazine.

Did Moniz Deserve the Nobel Prize?

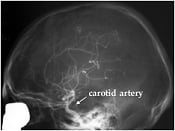

Moniz, who was born in 1874, was shot in the leg by a patient and had to spend the rest of his life in a wheel chair (he died in 1955). Moniz had problems with his hand and did not very often hold the knife himself. However, there is no doubt that it really was Moniz who initiated and managed to inspire enthusiasm for the importance of prefrontal leukotomy in the treatment of certain psychoses. The more sophisticated surgical methods, however, were developed by other people, primarily by Freeman and Watts but also by Lyerly-Poppen, Strecker and others. Moniz’s main interests were evidently encephalography, and cerebral arteriography. Already in the 1920s Moniz succeeded in making cerebral arteriographies possible by injections of a contrast agent containing iodine, an invention which made it possible to diagnose tumors and vascular deformities. Actually, I think there is no doubt that Moniz deserved the Nobel Prize.

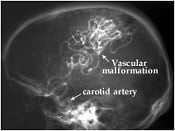

X-ray examination of brain vessels using the method – cerebral angiography – introduced by Moniz. A radio-opaque contrast medium has been injected into one of four neck vessels (carotid artery) supplying the brain. Normal case (left). A case of vascular malformation situated in the parietal (mid superior) part of the brain and fed by an enlarged artery (right).

Moniz’s life history contains a few surprising details. He grew up and was educated in Coimbra, but after having been professor there and also professor of neurology in Lisbon in 1911-14, he devoted some years to business and politics. Moniz became ambassador to Madrid in 1918 and in 1918-19 was minister for foreign affairs before returning to the Institute of Neurology in Lisbon.

Glossary

Affective disorders – all states where the patient’s mood is higher (manic or hypomanic states) or lower than normal, that is, various kinds of depression, for instance, involutional depression in old people with signs of ageing. (Manic-depressive psychosis is an older term for the same kind of disorders).

Cerebral angiography – an X-ray investigation of the blood vessels of the brain. The blood vessels are made visible by injecting a dye that is opaque to X-rays.

Cingulotomy and bilateral anterior capsulotomy – are methods used to destroy connections between cortical areas and basal ganglia, areas which have shown signs of hypermetabolism in tomographies. The operations may be accomplished by thermic coagulation with high frequency electric current or gamma radiation. In the former method electrodes are conveyed through two bore-holes, and the latter method is totally unbloody.

Electric convulsive therapy (E.C.T.) – is the most efficient treatment of severe depressions. A short electric stimulation results in seizures which last for about 30 seconds. Repeated five to eight times, 3 times a week, this will as a rule make the patient healthy again without any side effects, except for minor memory disturbances which disappear within 3-4 weeks.

Encephalography – any of various methods for recording the structure of the brain or the activity of the brain cells.

Hypoglycemic – a state in which blood glucose level is below normal.

Leukotomy/Lobotomy – leukotomy is the surgical operation of interrupting the pathways of white nerve fibers within the brain. Lobotomy was the name given to a prefrontal leukotomy in which the nerve fibers connecting the frontal lobe with other parts of the brain were cut.

Limbic system – situated in the temporal lobe of the brain, is a center of vegetative functions, emotional experience, behavior and consolidation of memories.

Neuroleptics – which were introduced with chlorpromazine in 1952, are the most effective drugs in the treatment of psychotic symptoms (hallucinations, delusions, so-called “positive” symptoms) in schizophrenia. Many of them, but not all, also have sedative properties.

Obsessive-compulsive states – are conditions in which the patient sometimes may be very incapacitated by intensive thoughts he can not get rid of (obsessions), or ridiculous, meaningless things he feels compelled to do over and over again in order to hinder his anxiety level from increasing to an intolerable level (compulsions).

Prefrontal (lobe) – the area of the brain at the very front of each cerebral hemisphere. This area is concerned with emotion, memory, learning, and social behaviour.

Psychoses – are the most severe mental disorders, that is, schizophrenia, affective psychoses and also severe mental states often with confusional symptoms produced by toxic agents.

Schizophrenia – a psychotic condition, is the most severe psychiatric disorder. There are various subtypes, but symptoms like hallucinations, paranoid reactions and a reduced emotional capacity (and ability to relate to other people) and, sometimes, even isolation in an autistic state are characteristic. Until the introduction of neuroleptics in 1952, a majority of beds in our mental hospitals were used by schizophrenics, many of them from the age of 20-30 until death. Thanks to neuroleptics, most schizophrenic patients can take care of themselves outside hospitals, but very few become totally healthy. Most of them have residual symptoms which often make it difficult for them to work full-time, at least in qualified professions.

Stereotactic – a stereotactic surgical procedure is one in which a deep-seated area of the brain is operated upon after its position has been established with great accuracy by three-dimensional measurements.

Tomography – the scanning of a particular part of the body using X-rays or ultrasound. Computerized tomography (CT) scan is an X-ray procedure in which a computer draws a map from the measured densities of the brain. This method produces a three-dimensional representation of the brain

Tranquillizers – are drugs with a sedative effect enabling an anxious patient to relax. Some of these drugs are neuroleptics, whereas others only have a relaxation effect of a rather short duration, for instance, benzodiazepines.

References

Hoffman, JL: Clinical observations concerning schizophrenic patients treated by prefrontal leukotomy. N. Engl. J. Med. 1949, 241:233-236.

Kalinowsky, LB and Scarff, JE: The selection of psychiatric cases for prefrontal lobotomy. Am. J. Psychiatry 1948, 105:81-85.

Menninger, WC: Facts and statistics of significance for psychiatry. Bull. Menninger Clin. 1948, 12:1-25.

Swayze II, VW: Frontal leukotomy and related psychosurgical procedures in the era before antipsychotics (1935-1954): A historical overview. Am. J. Psychiatry 1995, 152 (4):505-515.

Tooth GC, and Newton, MP: Leukotomy in England and Wales 1942-1954. London, Her Majesty’s Stationary Office, 1961.

* Bengt Jansson, born 1932. M.D. 1956, Ph.D. 1964 at Göteborg University, Sweden (Post-Partum Psychoses). Since 1976 Professor of Psychiatry at Karolinska Institutet, Sweden. Member of the Medical Nobel Assembly, 1976-97. Main research interest in psychiatry since many years: Transcultural Psychiatry.

First published 29 October 1998