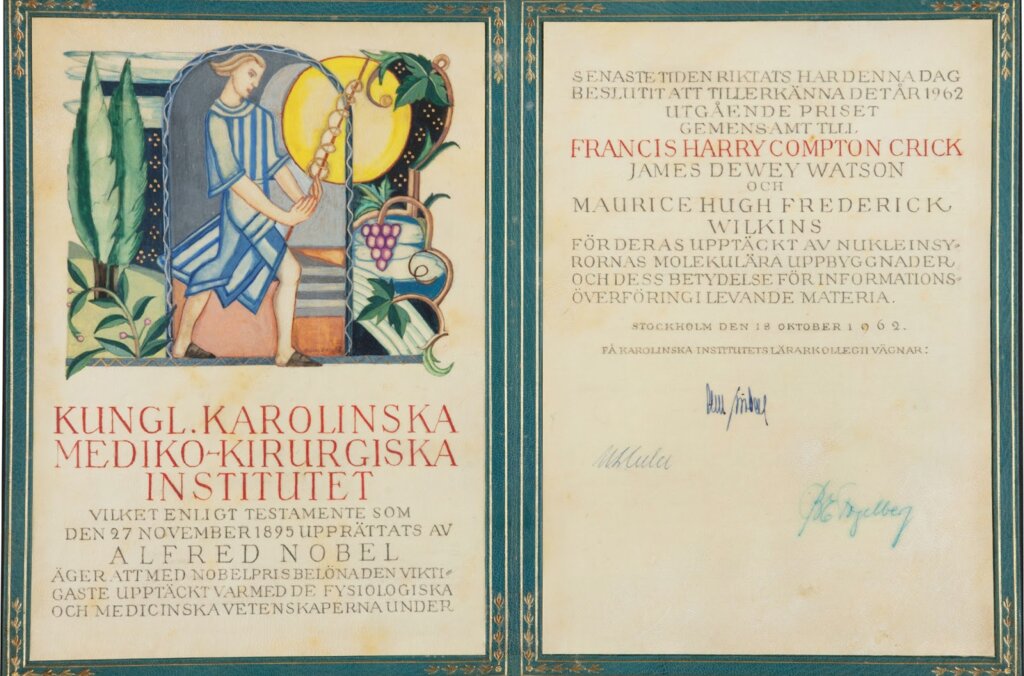

Francis Crick – Nobel diploma

Speed read: Deciphering life’s enigma code

In the mid-to-late 1940s, scientists began to suspect that the molecules that are responsible for heredity were not proteins, but in fact DNA, short for deoxyribonucleic acid. But how could a molecule long considered to be simple and inert hold the secret of life? The Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1962 was awarded to James Watson, Francis Crick and Maurice Wilkins for their discovery of the molecular structure of DNA, which helped solve one of the most important of all biological riddles.

Wilkins and his colleague Rosalind Franklin provided the key X-ray diffraction patterns that Watson and Crick used, as well as information from many other scientists, to build the definitive model of DNA’s structure. The structure, as simple and elegant as it is profound, shows that two long strands of DNA run in opposite directions and spiral around one another in the shape of a double helix. Another vital element in the structure is that four organic bases – known as adenine, thymine, cytosine and guanine – are paired in a specific manner between the two helices in such a way as to provide a natural scaffold for the two strands.

Watson and Crick’s structure of DNA could also explain how information is transferred in living material. The specific base pairing facilitates the perfect copying facility for heredity, while the specific order of bases forms the blueprint for the sequence of amino acids in a protein. DNA molecules can ‘unzip’ into two separate strands, and when the cell’s machinery creates matching strands, the specific pairing between the bases ensures that you get two faithful copies where you had one before. Watson and Crick’s paper revealing the structure, published in Nature on 25 April 1953, contains perhaps one of scientific literature’s most famous understatements: “It has not escaped our notice that the specific pairing we have postulated immediately suggests a possible copying mechanism for the genetic material.”

Perspectives: What is life?

Erwin Schrödinger’s idea that physics could help solve biological riddles was the spark that led many researchers to try to unlock the secrets behind our book of life, the structure of DNA.

The double helix structure of DNA is arguably the most recognizable icon in biology, so it might at first appear strange that two of the three men awarded the Nobel Prize for its discovery were physicists. However, as all three Laureates, Maurice Wilkins, James Watson and Francis Crick acknowledged, their interest in DNA was sparked not by a biologist, but by a series of lectures delivered by a physicist.

These lectures were published in a book in 1944 that sold more than 100,000 copies, ranking it among the most influential scientific writings of the 20th century. Less than 100 pages long, What is Life? is based on the lectures that Erwin Schrödinger gave at Trinity College in Dublin in February 1943.

Schrödinger, an Austrian physicist, had become famous in the 1920s for his work on quantum theory. Key amongst his achievements was his wave equation, for which he was awarded the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1933. Schrödinger had given up his position as a professor at the University in Berlin in 1933 in protest against Nazi persecutions of his Jewish colleagues. In 1940, after seven restless years of exile, Schrödinger accepted an invitation by the Irish premier Eamon de Valera, a mathematician by training, to join the newly founded Dublin Institute for Advanced Studies.

Schrödinger conceived the series of lectures he gave at the Institute to be “one small comment on a large and important question”. The question Schrödinger addressed was: “How can the events in space and time which take place within the spatial boundary of a living organism be accounted for by physics and chemistry?”

Schrödinger’s attempts to answer this question would influence a generation of physicists to apply their knowledge to solving biological problems. Schrödinger offered valuable insights into how physics could help solve issues like the basis of heredity. As Schrödinger wrote in his book, two great theories of physics and biology were born in 1900: Max Planck discovered quantum theory, and de Vries, Correns and Tschermak re-discovered Mendel’s forgotten paper on genetics. Yet, while quantum theory had fundamentally changed the perception of the world within three decades, geneticists were still more or less clueless about heredity, wrote Schrödinger.

Despite some progress in chromosome research, genes were still very much an abstract concept, and many biologists were still convinced by the idea of an immaterial ‘vital force’. One exception to this theory was a paper published by the German physicist Max Delbrück and the Russian geneticist Timofèeff-Ressovsky in 1935. They proposed that genes were large molecules, consisting of bonds of thousand of atoms. This exciting new perspective on genes provided the basis for Schrödinger’s lectures. “If the Delbrück picture should fail, we would have to give up further attempts,” said Schrödinger.

Looking at heredity from his perspective, Schrödinger argued that life could be thought of in terms of storing and passing on biological information. Understanding life, which would invariably involve discovering the gene, could possibly go beyond the laws of physics as was known at the time, he stated.

Building on this belief, Schrödinger proposed a mind-expanding metaphor in his last lecture. Because so much information had to be packed into every cell, it must be packed into what Schrödinger called a ‘hereditary code-script’ embedded in the molecular fabric of chromosomes. To understand life, then, we would have to identify these molecules, and crack their code.

Schrödinger’s metaphor of a readable book of life, a decipherable genetic code, might seem obvious now, but at the time this was a sensationally new concept. Schrödinger viewed the genes in each cell as resembling offices that produce orderly events. “Since we know the power this tiny central office has in the isolated cell, do they not resemble stations of local government dispersed through the body, communicating with each other with great ease, thanks to the code that is common to all of them?” asked Schrödinger. Even Schrödinger appreciated the scale of his suggestion, admitting “Well, this is a fantastic description, perhaps less becoming a scientist than a poet.”

Such a mind-expanding metaphor resonated loudly with scientists. “The notion that life might be perpetuated by means of an instruction book inscribed in a secret code appealed to me,” Watson would later say. The question was what sort of code could hold all the secrets of a living cell, and how could it make exact copies of itself every time a chromosome duplicates?

Uncanny Timing

However, the main reason behind the successful impact of What is Life? was due to a happy coincidence. In May 1943, Oswald Avery at the Rockefeller Institute in New York published the results of a study that at long last had discovered the source of heredity. To many people’s surprise, Avery’s experiments proved that it wasn’t proteins, as had been widely thought, but in fact a nucleic acid living in chromosomes that was long presumed to be inert, called DNA, short for deoxyribonucleic acid. So, just as Schrödinger’s suggestions about a readable book of life were being published, Avery had discovered the very code-script that scientists could now attempt to decipher.

Schrödinger’s concept of a highly complex molecular structure that controlled living processes was instrumental in changing Wilkins’ career. Wilkins had been involved in the Manhattan Project that created the atomic bomb during the Second World War. He became disillusioned with physics after seeing the fruits of these labours, and was looking for a new research field to explore.

One idea in particular struck a chord with Wilkins. Schrödinger proposed that a gene could be stable from one generation to another if it is an ‘aperiodic’ crystal – in other words, something with a regular but non-repeating structure. Schrödinger compared the difference in the structure of a normal and aperiodic crystal with the difference between ordinary wallpaper in which the same pattern is repeated again and again in a masterpiece of embroidery, such as a Raphael tapestry.

Schrödinger’s concept of defining genes in terms of crystals interested Wilkins as he had studied the way electrons move in perfect and irregular crystals for his PhD. In 1946, the physicist John Randall recruited Wilkins to a new biophysics laboratory in King’s College, London, that he was heading up. Randall wanted to hire physicists to work on problems in biology, and Wilkins jumped at the chance to work on proteins and DNA.

Crick thought the arguments that Schrödinger set out were not without its flaws, but he was still impressed by the book. Crick, also a physicist, had worked on magnetic mines for the Admiralty during the war, and had planned to stay on in military research. After reading What is Life?, he thought a physicist could do more about solving the secrets of life, and joined the Cavendish Laboratory in Cambridge to pursue the three-dimensional structure of proteins for his PhD.

To a student called James Watson in his final year at the University of Chicago, the book was an almost instant epiphany. Watson had planned to be a naturalist, but after reading the book he was convinced from Avery’s experiments that genes were molecules, and that he should discover the structure of the gene.

Watson travelled to Indiana University and the University of Copenhagen in pursuit of his obsession. During his time in Copenhagen, he attended a small conference on X-ray diffraction methods for determining the three-dimensional structure of molecules. To his delight, he chanced upon a talk by Wilkins, who was presenting data on X-ray diffraction studies of DNA. The array of spots on the photograph indicated that DNA must have a regular structure, and solving this could help reveal the nature of the gene. An excited Watson tried to talk to Wilkins afterwards, but the conversation went no further than a self-evident declaration from Wilkins that much hard work lay ahead.

Watson’s PhD supervisor arranged for him to take up a position at the Cavendish Laboratory, and he arrived in Cambridge in September 1951. Three weeks later Watson discovered that he was sharing space in the biochemistry room with Crick. Watson describes their first meeting as an instantaneous meeting of minds. Crick was interested in the fact that Watson’s mission was to discover the structure of DNA, and within minutes they were guessing what the structure could look like.

But how could they begin to find out the truth? To bring them up to speed on the latest findings on DNA’s structure, Crick invited an old friend to his house for Sunday lunch. The friend, Wilkins, accepted the invitation, and the rest, as they say is history.

Watson and Crick’s paper on the double helix structure of DNA was published in the journal Nature on 25 April 1953, and a grateful Crick wrote to Schrödinger on 12 August 1953 to express his gratitude for being an influence. “Watson and I were once discussing how we came to enter the field of molecular biology, and we discovered that we had both been influenced by your little book What is Life?” wrote Crick. “We thought you might be interested in the enclosed reprints – you will see that it looks as though your term ‘aperiodic crystal’ is going to be a very apt one.”

Bibliography

Blumenberg, Hans: Der genetische Code und seine Leser. In: Die Lesbarkeit der Welt. Suhrkamp, Frankfurt 1999, S. 372–409.

Gribbin, John: The scientists. A history of science told through the lives of its greatest inventors. Random House, New York, 2004.

Schrödinger, Erwin: What is Life? The physical aspect of the living cell. With Mind and Matter and Autobiographical Sketches, Cambridge University Press, 1992.

Watson, James D.: The Double Helix. A personal account of the discovery of the structure of DNA. Penguin Books, Harmondsworth, 1969.

Watson, James D.: DNA: The Secret of Life. Arrow Books, 2004.

Wilkins, Maurice H.F., The molecular configuration of nucleic acids, Nobel lecture, December 11, 1962.

Wilkins, Maurice: The Third Man of the Double Helix. An Autobiography. Oxford, 2003.

Maurice Wilkins – Other resources

Links to other sites

On Maurice Wilkins and The Race for DNA from Oregon State University

DNA from the beginning from Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory

DNA interactive from Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory

Francis Crick – Other resources

Links to other sites

On Francis Crick and The Race for DNA from Oregon State University

DNA interactive from Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory

On Francis Crick from PBS Online

The Francis Crick Papers at the U.S. National Library of Medicine

Video

Interview with Francis Crick and James Watson at the UT Southwestern Medical Center, November 2013.

James Watson – Other resources

Links to other sites

On James Watson and The Race for DNA from Oregon State University

The Academy of Achievement – Profile, Biography and Interview with James D. Watson

DNA from the beginning from Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory

DNA interactive from Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory

Videos

James Watson: ‘How we discovered DNA’ from TED Talks.

Interview with James Watson and Francis Crick at the UT Southwestern Medical Center, November 2013.

James Watson – Photo gallery

1 (of 3) Portrait of James Watson.

Source: U.S National Library of Medicine. Photographer unknown. Kindly provided by U.S National Library of Medicine.

2 (of 3) Francis Crick and James D. Watson walk along the Cambridge backs. Photo taken in 1953.

Source: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Archives. Photographer unknown. Kindly provided by Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Archives.

3 (of 3) Original model of the structure of DNA, 1953.

Source: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Archives. Photographer unknown. Kindly provided by Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Archives.

Francis Crick – Photo gallery

1 (of 4) Francis Crick in his office. Behind him is a model of the human brain.

Source: Public Library of Science Journal. Licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 2.5 Generic license. Photographer: Marc Lieberman.

2 (of 4) Telegram to Francis Crick informing him about being awarded the Nobel Prize, 18 October 1962.

Credit: The Nobel Assembly at Karolinska Institut

3 (of 4) Francis Crick and James D. Watson walk along the Cambridge backs. Photo taken in 1953.

Source: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Archives. Photographer unknown. Kindly provided by Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Archives.

4 (of 4) Original model of the structure of DNA, 1953.

Source: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Archives. Photographer unknown. Kindly provided by Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Archives.

Maurice Wilkins – Nobel Lecture

Nobel Lecture, December 11, 1962

The Molecular Configuration of Nucleic Acids

Read the Nobel Lecture

Pdf 687 kB

James Watson – Banquet speech

James Watson’s speech at the Nobel Banquet in Stockholm, December 10, 1962

Your Majesties, Your Royal Highnesses, Your Excellencies, Ladies and Gentlemen.

Francis Crick and Maurice Wilkins have asked me to reply for all three of us. But as it is difficult to convey the personal feeling of others, I must speak for myself. This evening is certainly the second most wonderful moment in my life. The first was our discovery of the structure of DNA. At that time we knew that a new world had been opened and that an old world which seemed rather mystical was gone. Our discovery was done using the methods of physics and chemistry to understand biology. I am a biologist while my friends Maurice and Francis are physicists. I am very much the junior one and my contribution to this work could have only happened with the help of Maurice and Francis. At that time some biologists were not very sympathetic with us because we wanted to solve a biological truth by physical means. But fortunately some physicists thought that through using the techniques of physics and chemistry a real contribution to biology could be made. The wisdom of these men in encouraging us was tremendously important in our success. Professor Bragg, our director at the Cavendish and Professor Niels Bohr often expressed their belief that physics would be a help in biology. The fact that these great men believed in this approach made it much easier for us to go forward. The last thing I would like to say is that good science as a way of life is sometimes difficult. It often is hard to have confidence that you really know where the future lies. We must thus believe strongly in our ideas, often to point where they may seem tiresome and bothersome and even arrogant to our colleagues. I knew many people, at least when I was young, who thought I was quite unbearable. Some also thought Maurice was very strange, and others, including myself, thought that Francis was at times difficult. Fortunately we were working among wise and tolerant people who understood the spirit of scientific discovery and the conditions necessary for its generation. I feel that it is very important, especially for us so singularly honored, to remember that science does not stand by itself, but is the creation of very human people. We must continue to work in the humane spirit in which we were fortunate to grow up. If so, we shall help insure that our science continues and that our civilization will prevail. Thank you very much for this very deep honor.