BARBARA MCCLINTOCK

Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine 1983

Throughout her career, Barbara McClintock studied the cytogenetics of maize, making discoveries so far beyond the understanding of the time that other scientists essentially ignored her work for more than a decade. But she persisted, trusting herself and the evidence under her microscope.

A few labelled samples of Barbara McClintock’s maize, with microscope.

Photo: Smithsonian Institution. National Museum of American History

Corn stalk specimen.

Photo: Courtesy of the Barbara McClintock Papers, American Philosophical Society

Barbara McClintock almost didn’t go to college. She was a talented student, but her mother believed a college degree would harm her chances of marriage and vetoed her plan to go to Cornell.

The McClintock children, ca. 1907. Barbara McClintock is second from the right.

Photo: National Institutes of Health. Courtesy of the Barbara McClintock Papers, American Philosophical Society. Photographer unknown

A McClintock family photograph, ca. 1914. Barbara McClintock is third from the right, leaning on the piano.

Photo: National Institutes of Health. Courtesy of the Barbara McClintock Papers, American Philosophical Society.

Fortunately, McClintock’s father returned from the Army Medical Corps in France in time to intervene. In 1919, at the age of 17, McClintock enrolled in the Cornell College of Agriculture. She thrived at college: she joined the student government, played banjo in a jazz band, and excelled in the classroom. It was there that she took the course that would change the course of her life: genetics.

Genetics as a discipline was still new in the 1920s; Cornell offered only one undergraduate course. But McClintock took to it immediately, conceiving a lifelong interest in the field of cytogenetics – the study of chromosomes and their genetic expression.

“No two plants are exactly alike. They’re all different, and as a consequence, you have to know that difference. I start with the seedling and I don’t want to leave it. I don’t feel I really know the story if I don’t watch the plant all the way along. So I know every plant in the field. I know them intimately. And I find it a great pleasure to know them.”

Barbara McClintock

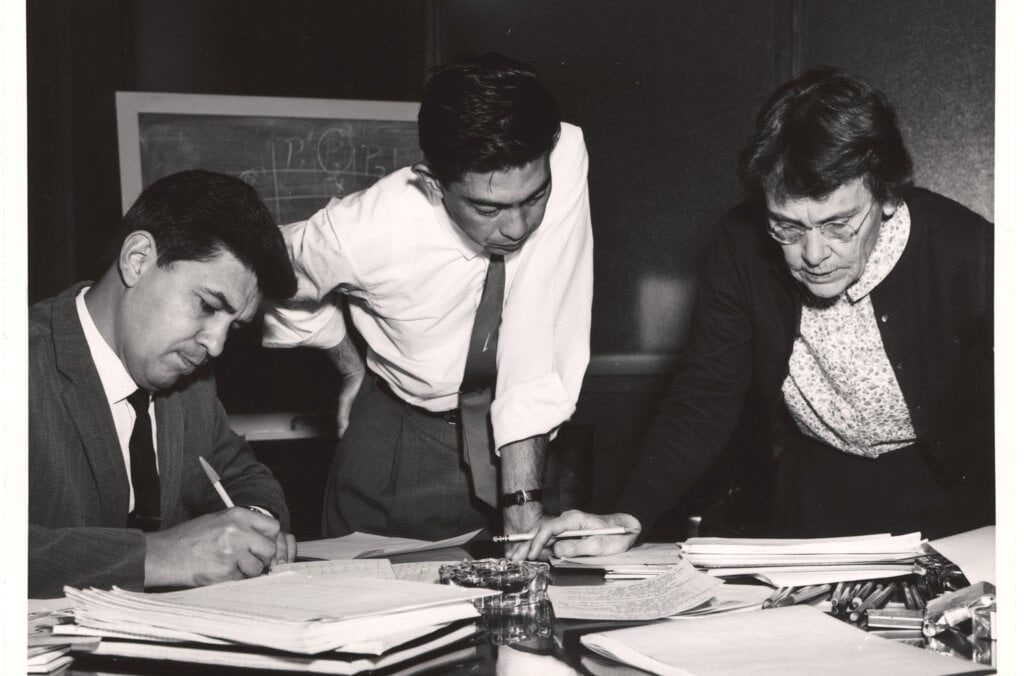

A letter from Lewis Stadler (pictured) to Milislav Demerec. A close friend and supporter from Cornell days, Stadler had helped McClintock procure a position at the University of Missouri. Six years later, Demerec brought her to Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory on leave from the university. Stadler writes that although he wants McClintock to return to Missouri, “I hope she will stay at Cold Spring Harbor if she is convinced that would be better for her work.”

Courtesy of Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory

Page two from a letter from Lewis Stadler (pictured) to Milislav Demerec. A close friend and supporter from Cornell days, Stadler had helped McClintock procure a position at the University of Missouri. Six years later, Demerec brought her to Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory on leave from the university. Stadler writes that although he wants McClintock to return to Missouri, “I hope she will stay at Cold Spring Harbor if she is convinced that would be better for her work.”

Courtesy of Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory

Barbara McClintock’s colleague and supporter Lewis Stadler, with geneticist Esther M. Lederberg at the University of Missouri in the 1950s

Courtesy of Joshua Lederberg

She earned her bachelor’s, master’s and doctoral degrees at Cornell and had great success in her research on the cytogenetics of maize. Even so, it wasn’t easy to find a permanent position in the midst of the Depression. Finally, McClintock was hired as an assistant professor at the University of Missouri in 1936.

McClintock loved working in the lab. “I was just so interested in what I was doing I could hardly wait to get up in the morning and get at it,” she once said.

But for her, teaching was a distraction. She left her university job in 1941 for Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, a research facility funded by the Carnegie Institution. Freed to focus exclusively on her experiments, McClintock stayed at Cold Spring Harbor until her retirement in 1967 – and even beyond, as a scientist emerita, until her death at the age of 90.

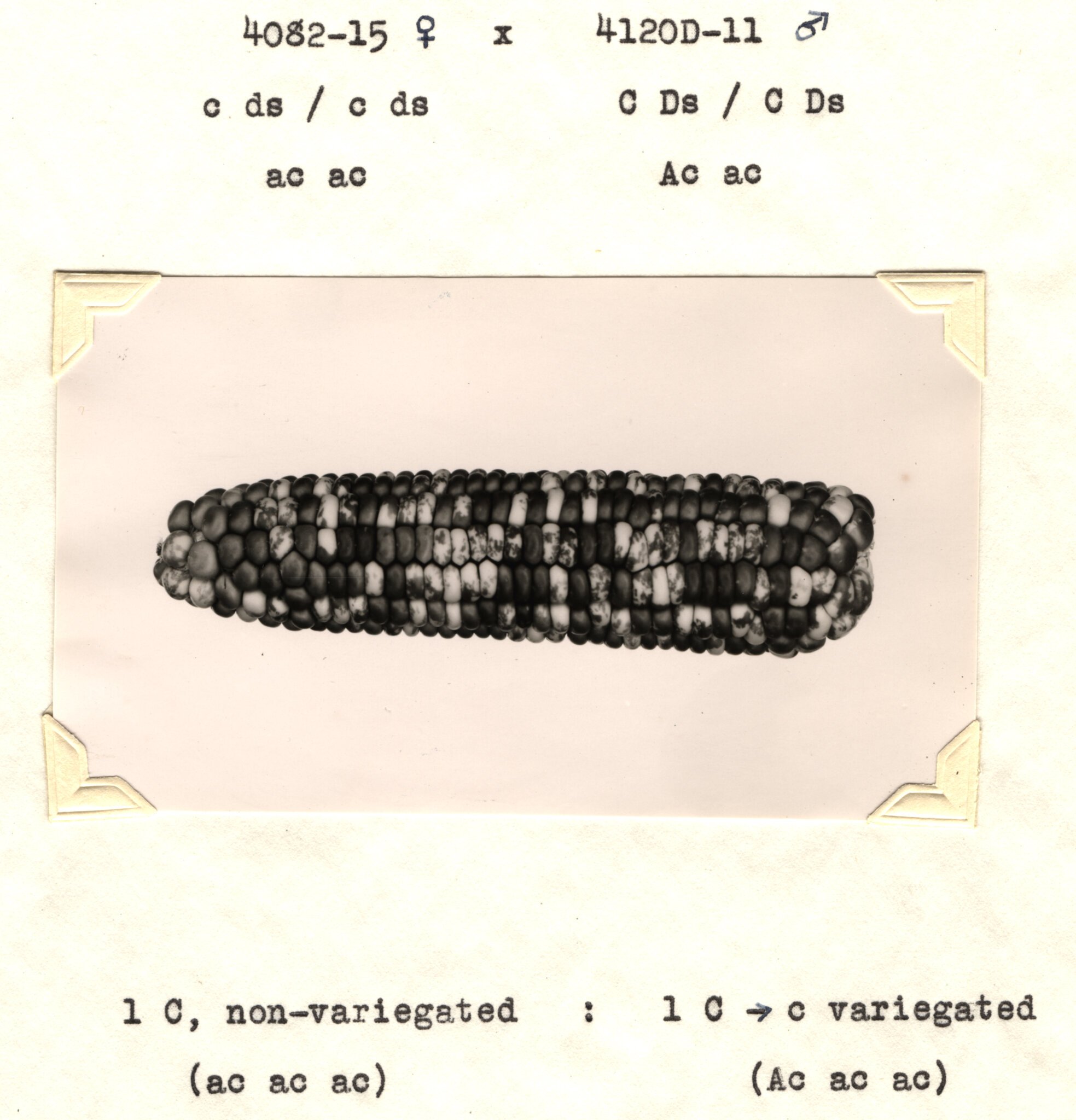

Early in her research at Cold Spring Harbor, McClintock began to study the mosaic colour patterns of maize at the genetic level. She had noted that the kernel patterns were too unstable, and changed too frequently over the course of several generations, to be considered mutations. What was responsible for this? The answer contradicted prevailing genetic theory.

Labelled maize. Barbara McClintock discovered that genes could “jump” by studying generational mutations in maize.

Photo: Courtesy of Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory. Photo: Jan Eve Olsson

An illustration of corn kernel specimens, included in Barbara McClintock’s article in the ‘Cold Spring Harbor Symposia on Quantitative Biology’ in 1951.

Photo: Courtesy of the Barbara McClintock Papers, American Philosophical Society

As McClintock observed by studying successive generations of maize plants, instead of being locked into place giving fixed instructions from generation to generation, some genes could move around or “transpose” within chromosomes, switching physical traits on or off according to certain “controlling elements.”

Aware that her work departed from the common wisdom, McClintock put off publishing her theories on genetic transposition and controlling elements until other researchers had confirmed her results. At last, in the summer of 1951, she gave a lecture on her findings at the annual symposium at Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory. It didn’t go well. As she later recalled it, the audience was either perplexed by or hostile to her theories. “They thought I was crazy, absolutely mad.”

“I just knew I was right. Anybody who had had that evidence thrown at them with such abandon couldn’t help but come to the conclusions I did about it.”

Barbara McClintock

In the face of such resistance to her theories, McClintock stopped publishing and lecturing – she stopped trying to convince others – but she never stopped pursuing her theories. “I just knew I was right,” she said later. “Anybody who had had that evidence thrown at them with such abandon couldn’t help but come to the conclusions I did about it.”

McClintock’s diagram of the BreakageFusionBridge cycle.

Courtesy of the Barbara McClintock Papers, American Philosophical Society

Corn specimens photographed in 1966, when Barbara McClintock was studying the evolution of maize in South America.

Photo: Courtesy of the Barbara McClintock Papers, American Philosophical Society

Finally, in the mid-1960s, the scientific community began to come to the same conclusions, validating her findings and giving her the credit that was long overdue. McClintock received the Nobel Prize more than 30 years after making the discoveries for which she was honoured.

“Over the many years, I truly enjoyed not being required to defend my interpretations. I could just work with the greatest of pleasure. I never felt the need nor the desire to defend my views. If I turned out to be wrong, I just forgot that I ever held such a view. It didn’t matter.”

Barbara McClintock

Barbara McClintock made discovery after discovery over the course of her long career in cytogenetics. But she is best remembered for discovering genetic transposition (“jumping genes”). Understanding the phenomenon is still fundamental to understanding genetics, as well as related concepts in medicine, evolutionary biology, and more.

Beyond her discoveries, though, McClintock’s legacy is one of uncommon persistence. As she put it, “If you know you are on the right track, if you have this inner knowledge, then nobody can turn you off… no matter what they say.”

Barbara McClintock – Nobel Lecture

Barbara McClintock held her Nobel Lecture on 8 December 1983, at Karolinska Institutet, Stockholm. He was presented by Professor Nils Ringertz, Member of the Nobel Committee for Physiology or Medicine.

Read the Nobel Lecture

Pdf 502 kB

Barbara McClintock – Other resources

Links to other sites

The Barbara McClintock Papers at the U.S. National Library of Medicine

‘Barbara McClintock and Transposable Genetic Elements’ from DOE R&D Accomplishments

Barbara McClintock – Banquet speech

Barbara McClintock’s speech at the Nobel Banquet, December 10, 1983

Your Majesties, Your Royal Highnesses, Ladies and Gentlemen

I am delighted to be here, and charmed by the warmth of the Swedish people. And I wish to thank them for their many courtesies.

I understand I am here this evening because the maize plant, with which I have worked for many years, revealed a genetic phenomenon that was totally at odds with the dogma of the times, the mid-nineteen forties. Recently, with the general acceptance of this phenomenon, I have been asked, notably by young investigators, just how I felt during the long period when my work was ignored, dismissed, or aroused frustration. At first, I must admit, I was surprised and then puzzled, as I thought the evidence and the logic sustaining my interpretation of it, were sufficiently revealing. It soon became clear, however, that tacit assumptions – the substance of dogma – served as a barrier to effective communication. My understanding of the phenomenon responsible for rapid changes in gene action, including variegated expressions commonly seen in both plants and animals, was much too radical for the time. A person would need to have my experiences, or ones similar to them, to penetrate this barrier. Subsequently, several maize geneticists did recognize and explore the nature of this phenomenon, and they must have felt the same exclusions. New techniques made it possible to realize that the phenomenon was universal, but this was many years later. In the interim I was not invited to give lectures or seminars, except on rare occasions, or to serve on committees or panels, or to perform other scientists’ duties. Instead of causing personal difficulties, this long interval proved to be a delight. It allowed complete freedom to continue investigations without interruption, and for the pure joy they provided.

Barbara McClintock – Photo gallery

HRH Prince Bertil of Sweden and Barbara McClintock, checking out the programme for the evening, at the Nobel Banquet in the Stockholm City Hall, Sweden, on 10 December 1983.

Copyright © Svensk Reportagetjänst 1983

Photo: Ulf Blumenberg

Barbara McClintock delivering her Nobel Lecture at Karolinska Institutet in Stockholm, 8 December 1983.

Source: National Institutes of Health. Courtesy of the Barbara McClintock Papers, American Philosophical Society

Photographer unknown

Barbara McClintock with Alfred Hershey, 1969 Nobel Laureate in Physiology or Medicine. Date unknown.

Source: National Institutes of Health. Courtesy of the Barbara McClintock Papers, American Philosophical Society

Photographer unknown

Barbara McClintock with staff at the Banbury Center, Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory. Barbara McClintock is standing third from the left in the first row. Photo taken in August, 1984.

Source: National Institutes of Health. Courtesy of the Barbara McClintock Papers, American Philosophical Society

Photographer unknown

Photograph of Barbara McClintock's five ears of corn and a microscope.

Source: Smithsonian Institution. National Museum of American History

Photographer unknown

Barbara McClintock in the lab at Cold Spring Harbor, April, 1963.

National Institutes of Health. Courtesy of the Barbara McClintock Papers, American Philosophical Society. Photographer unknown

Barbara McClintock arrived at Cold Spring Harbor on Long Island in 1941 and spent most of her remaining research years at the facility. Photo taken ca 1950.

Source: National Institutes of Health. Courtesy of the Barbara McClintock Papers, American Philosophical Society

Photographer unknown

Barbara McClintock shown in her laboratory at the Department of Genetics, Carnegie Institution at Cold Spring Harbor, New York, 1947.

Source: Smithsonian Institution/Science Service; Restored by Adam Cuerden, via Wikimedia Commons

Photographer unknown

Barbara McClintock with her family. From left to right: Mignon, Malcolm Rider "Tom", Barbara, Marjorie, and Sara (at the piano). Photo taken ca 1914.

Source: National Institutes of Health. Courtesy of the Barbara McClintock Papers, American Philosophical Society

Photographer unknown

The McClintock siblings. From the left: Mignon, Malcolm Rider "Tom", Barbara, and Marjorie. Photo taken in 1907.

Source: National Institutes of Health. Courtesy of the Barbara McClintock Papers, American Philosophical Society

Photographer unknown

Barbara McClintock – Prize presentation

Watch a video clip of the 1983 Nobel Laureate in Physiology or Medicine, Barbara McClintock, receiving her Nobel Prize medal and diploma during the Nobel Prize Award Ceremony at the Concert Hall in Stockholm, Sweden, on 10 December 1983.

The Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine 1983

Barbara McClintock – Biographical

In the fall of 1921 I attended the only course in genetics open to undergraduate students at Cornell University. It was conducted by C. B. Hutchison, then a professor in the Department of Plant Breeding, College of Agriculture, who soon left Cornell to become Chancellor of the University of California at Davis, California. Relatively few students took this course and most of them were interested in pursuing agriculture as a profession. Genetics as a discipline had not yet received general acceptance. Only twenty-one years had passed since the rediscovery of Mendel’s principles of heredity. Genetic experiments, guided by these principles, expanded rapidly in the years between 1900 and 1921. The results of these studies provided a solid conceptual framework into which subsequent results could be fitted. Nevertheless, there was reluctance on the part of some professional biologists to accept the revolutionary concepts that were surfacing. This reluctance was soon dispelled as the logic underlying genetic investigations became increasingly evident.

When the undergraduate genetics course was completed in January 1922, I received a telephone call from Dr. Hutchison. He must have sensed my intense interest in the content of his course because the purpose of his call was to invite me to participate in the only other genetics course given at Cornell. It was scheduled for graduate students. His invitation was accepted with pleasure and great anticipations. Obviously, this telephone call cast the die for my future. I remained with genetics thereafter.

At the time I was taking the undergraduate genetics course, I was enrolled in a cytology course given by Lester W. Sharp of the Department of Botany. His interests focused on the structure of chromosomes and their behaviors at mitosis and meiosis. Chromosomes then became a source of fascination as they were known to be the bearers of “heritable factors”. By the time of graduation, I had no doubts about the direction I wished to follow for an advanced degree. It would involve chromosomes and their genetic content and expressions, in short, cytogenetics. This field had just begun to reveal its potentials. I have pursued it ever since and with as much pleasure over the years as I had experienced in my undergraduate days.

After completing requirements for the Ph.D. degree in the spring of 1927, I remained at Cornell to initiate studies aimed at associating each of the ten chromosomes comprising the maize complement with the genes each carries. With the participation of others, particularly that of Dr. Charles R. Burnham, this task was finally accomplished. In the meantime, however, a sequence of events occurred of great significance to me. It began with the appearance in the fall of 1927 of George W. Beadle (a Nobel Laureate) at the Department of Plant Breeding to start studies for his Ph.D. degree with Professor Rollins A. Emerson. Emerson was an eminent geneticist whose conduct of the affairs of graduate students was notably successful, thus attracting many of the brightest minds. In the following fall, Marcus M. Rhoades arrived at the Department of Plant Breeding to continue his graduate studies for a Ph.D. degree, also with Professor Emerson. Rhoades had taken a Masters degree at the California Institute of Technology and was well versed in the newest findings of members of the Morgan group working with Drosophila. Both Beadle and Rhoades recognized the need and the significance of exploring the relation between chromosomes and genes as well as other aspects of cytogenetics. The initial association of the three of us, followed subsequently by inclusion of any interested graduate student, formed a close-knit group eager to discuss all phases of genetics, including those being revealed or suggested by our own efforts. The group was self-sustaining in all ways. For each of us this was an extraordinary period. Credit for its success rests with Professor Emerson who quietly ignored some of our seemingly strange behaviors.

Over the years, members of this group have retained the warm personal relationship that our early association generated. The communal experience profoundly affected each one of us.

The events recounted above were, by far, the most influential in directing my scientific life.

| Born |

| Hartford, Connecticut, U.S.A, 16 June, 1902 |

| Secondary Education |

| Erasmus Hall High School, Brooklyn, New York. |

| Earned Degrees |

| B.S. Cornell University, Ithaca, New York, 1923 |

| M.A. Cornell University, Ithaca, New York, 1925 |

| Ph.D. Cornell University, Ithaca, New York, 1927 |

| Positions held |

| Instructor in botany, Cornell University, 1927-1931 |

| Fellow, National Research Council, 1931-1933 |

| Fellow, Guggenheim Foundation, 1933-1934 |

| Research Associate, Cornell University, 1934-1936 |

| Assistant Professor, University of Missouri, Columbia, Missouri, 1936-1941 |

| Staff Member, Carnegie Institution of Washington, Cold Spring Harbor, New York, 1942-1967 |

| Distinguished Service Member, Carnegie Institution of Washington, Cold Spring Harbor, New York, 1967 to Present Visiting Professor, California Institute of Technology, 1954 |

| Consultant, Agricultural Science Program, The Rockefeller Foundation, 1963-1969 |

| Andrew D. White Professor-at-Large, Cornell University, 1965-1974 |

| Honorary Doctor of Science |

| University of Rochester, 1947 |

| Western College for Women, 1949 |

| Smith College, 1957 |

| University of Missouri, 1968 |

| Williams College, 1972 |

| The Rockefeller University, 1979 |

| Harvard University, 1979 |

| Yale University, 1982 |

| University of Cambridge, 1982 |

| Bard College, 1983 |

| State University of New York, 1983 |

| New York University, 1983 |

| Honorary Doctor of Humane Letters |

| Georgetown University, 1981 |

| Awards |

| Achievement Award, Association of University Women, 1947 |

| Merit Award, Botanical Society of America, 1957 |

| Kimber Genetics Award, National Academy of Sciences, 1967 |

| National Medal of Science, 1970 |

| Lewis S. Rosenstiel Award for Distinguished Work in Basic Medical Research, 1978 |

| The Louis and Bert Freedman Foundation Award for Research in Biochemistry, 1978 |

| Salute from the Genetics Society of America, August 18, 1980 |

| Thomas Hunt Morgan Medal, Genetics Society of America, June, 1981 |

| Honorary Member, The Society for Developmental Biology, June, 1981 |

| Wolf Prize in Medicine, 1981 |

| Albert Lasker Basic Medical Research Award, 1981 |

| MacArthur Prize Fellow Laureate, 1981 |

| Honorary Member, The Genetical Society, Great Britain, April, 1982 |

| Louisa Gross Horwitz Prize for Biology or Biochemistry, 1982 |

| Charles Leopold Mayer Prize, Académie des Sciences, Institut de France, 1982 |

This autobiography/biography was written at the time of the award and later published in the book series Les Prix Nobel/ Nobel Lectures/The Nobel Prizes. The information is sometimes updated with an addendum submitted by the Laureate.

Barbara McClintock died on September 2, 1992.

In Memoriam – Barbara McClintock

In Memoriam – Barbara McClintock

by Howard Green*

This article was published on 12 June 1999.

To paraphrase George Orwell, every person is unique, but some are more unique than others. There has never been anyone like Barbara McClintock in this world, nor ever will be. She was not simply a representative of a type. Some have considered her as an eccentric, others as a heroine of Science, and still others as a model to be imitated. I would like to tell you how I think of her.

Barbara McClintock was a woman who rejected a woman’s life for herself. She began to do it as a small child and never deviated. Her childhood was not a happy one, and perhaps this provided the force, the moral tension that was so strong in her and so necessary for the life she lived. And we must not forget that at the foundation of every creative life there lies a sense of personal inadequacy that energizes the struggle. This sense was strong in Barbara.

Barbara deliberately chose a solitary life without encumbrances, but she did not reject womanhood. In a feminine way, she once said to me “I cannot fight for myself, but I can fight for others.” In a time of confusion about such matters, it is important to note that Barbara did not fight against herself by choosing a path that was inconsistent with her nature or her capacity. This is why she could, at the end, say “I have lived a wonderful life and I have no regrets about it.” This does not mean that Barbara’s life of isolation protected her from inner storms and passions. On the contrary, she was familiar with periods of depression, sense of futility and, yes, tears of frustration and rage. Yet her final judgment on her life was strongly affirmative.

Science is not a career, and when it is made into one, it risks becoming falsified. As a scientist, Barbara was a prototypic non-careerist. This was not because she restrained a natural impulse to do otherwise, but because she could not imagine science as a vehicle for personal advancement. Barbara was successful in science at an early age and received general recognition at the time. But later, during the fifties and sixties, when she was doing her most original work, she was ignored to such an extent that she did not even want to publish. From time to time, her morale was low, even though she was utterly confident of her most important discovery: the mobility of genetic elements. We are all, unfortunately, dependent on recognition. We grow with it and suffer without it. When transposons were demonstrated in bacteria, yeast and other organisms, Barbara rose to a stratospheric level in the general esteem of the scientific world and honors were showered upon her. But she could hardly bear them. She felt obliged to submit to them: it was not joy or even satisfaction that she experienced; it was martyrdom! To have her work understood and acknowledged was one thing, but to make public appearances and submit to ceremonies was quite another.

Barbara did not permit her inner disturbances to unsettle the course of her life or her work. This was possible only because she was so permeated by sincerity. Her accomplishments in science depended on her respect for the way things were and not on her need to discover something. Some have spoken of Barbara’s way of understanding as that of a mystic and I think there are grounds for this view. For Barbara, Truth had a mystical origin, whether outside or inside herself and she had a deeply respectful attitude toward it. Her slowness in publication was in part because, as she once said to me, “I knew there must be no mistake.” Everyone who knew Barbara knew that if she affirmed something to be so, her verdict would be correct. I felt this very strongly and if I sometimes found it difficult to understand her explanations, I didn’t worry much about it; I was confident of her conclusions. She was a kind of mystic genius, in the sense that she knew things that she could not explain, and so it was sometimes impossible to understand how she knew what she knew.

Her way of comprehending was swift and direct. Her extraordinary grasp of cytology and genetics does not account for her discoveries. These depended on something more, which I will call insight. This is something she had about people, too. She had strong reactions to them and was particularly sensitive to what was not quite right about them. She was not fooled or foolable. Her judgments were not put-downs and had no tinge of malice, but they were based on a no-longer-current way of looking at people and taking their measure. They were not value-free because Barbara had values. Perhaps few people know this, but she was not part of our compassionate age and did not share its acceptance of almost anything. With respect to the formation of young scientists, she didn’t approve of all the tender, loving care accorded them by those in charge. “What’s the fuss about students?” she once asked me. “Let them sink or swim!”

Among her talents was the ability to dominate those rebellious tendencies in herself that were in conflict with what she desired herself to be. She had a Yogi-like ability to control pain. When she went to the dentist she assured him not to worry about inflicting pain because, by an effort of mind, she would not feel any. This piece of information may have raised the dentist’s eyebrows, but the result was as she predicted.

There are some for whom life is mainly serious and there are others for whom life is mainly laughter. Awful are those lives that are all one or all the other. Barbara took life mainly as serious, but she appreciated good laughs and we had many together. These were sometimes provoked by gentle teasing on my part. I enjoyed teasing Barbara and I think she rather liked it, too. Perhaps it was a kind of man-woman interaction. I did much of the teasing during the period of her public martyrdom.

Most of our conversations during the last 35 years took place by telephone. Barbara was wearied by her numerous visitors; many of those who intruded did not understand her need for privacy. She felt best when she was alone in her laboratory-nest. For the most part, I respected that feeling, particularly in her later years. But in June 1992, I made an unannounced visit to Cold Spring Harbor. At first, she was flustered and maybe even a little panicked. We went for a walk together and later sat in her little living room. When it was time for me to leave, she followed me to the door, stepped outside and looked at me intently as I walked away. When I turned round to wave, we stared at each other, both knowing that it was the last time. Only rarely in life does one have the opportunity to say good-bye at the right time.

In the following few months, we talked quite often by telephone. She seemed to be in a state of further decline. A week before her death, I sent her a book on the recent glacial epoch. She began to read it immediately and during our last telephone conversation, she told me with enthusiasm how much she was enjoying it. Her interest in the world and nature was back and I could not detect the feeling of “it’s all over, I’m ready to go” that she had expressed to me so clearly and decisively during the previous months. But I knew it was still there, if submerged, and at the end it surfaced again to Joan Marshak, whose personality and care Barbara so greatly appreciated and who was with her at the end. Barbara had decided that it was time to die and Barbara always did what she wanted.

I cannot explain the basis for our friendship. We were almost a generation apart in age, very different in background and upbringing, in temperament and in habits, even in scientific interests. But we nearly always understood each other and each of us could declare any thoughts without reservations. There was no tinge of interest in our relations: they were entirely gratuitous. I can say that knowing Barbara has been one of the great experiences of my life and the fact that she is gone makes me think of an extinct species or a miraculous creation that will never again be seen in the world. There are scientists whose discoveries greatly transcend their personalities and their humanity. But those in the future who will know of Barbara only her discoveries will know only her shadow. If she had made no important discoveries, I would feel about her almost as I do now. Those of us who knew her will preserve their memory of her uniqueness and marvel at what genes and experience gave to her alone.

* Howard Green is the George Higginson Professor of Cell Biology at Harvard Medical School. His scientific contributions include the development of the cell line 3T3, a general method of assigning human genes to specific chromosomes, the formation of adipose cells in culture, and the growth and differentiation of human keratinocytes. The cultivation of epidermal keratinocytes elaborated in his laboratory permitted the first use of cultured cells for the treatment of human disease.

First published 12 June 1999