Baroness Bertha Felicie Sophie von Suttner, born Countess Kinsky in Prague, was the posthumous daughter of a field marshal and the granddaughter, on her mother’s side, of a cavalry captain …

Bertha von Suttner – Speed read

Bertha von Suttner was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize for her courageous opposition to the horrors of war.

Full name: Baroness Bertha Sophie Felicita von Suttner, née Countess Kinsky von Chinic und Tettau

Born: 19 June 1843 in Prague, Austrian Empire (now Czech Republic)

Died: 21 June 1914 in Vienna, Austria

Date awarded: 10 December 1905

The first woman to receive the peace prize

Peace advocates in Europe and the USA rejoiced when Austrian baroness Bertha von Suttner received the peace prize in 1905. Her 1889 novel Lay Down Your Arms! brought her worldwide renown. A scathing critique of war and militarism, the book appeared in numerous editions in several languages. In a short time she became one of the leaders of the international peace movement, helping to found the Austrian Peace Union and participating at peace congresses in Europe and the USA. Her energy and conviction made her a central figure in these male-dominated fora. At the dawn of the 20th century, few could write or speak about peace and disarmament with greater authority than Bertha von Suttner. She firmly believed that social development would lead to peace and happiness. She said, “From beneath the old, the new and promising is breaking through.”

“Quite apart from the peace movement … there is taking place in the world a process of internationalization and unification. Factors contributing to the development of this process are technical inventions, improved communications, economic interdependence, and closer international relations.”

Bertha von Suttner, Nobel Lecture, 18 April 1906. Quoted from Nobel Lectures Peace 1901-25.

| Futurist optimism The belief that living conditions for humankind will improve in the future. This notion was especially popular in the West before WWI due to innovations in science and research and international treaties aimed at preventing war. |

Lay down your arms!

The novel’s heroine is the beautiful Martha, daughter of an Austrian general. An officer’s wife, she is widowed at a young age and left with a young son. She again marries an officer and again sees her husband head off to war. A cholera epidemic after the war costs Martha’s father and siblings their lives, but her husband survives and the two decide to dedicate their lives to the cause of peace. Bertha von Suttner’s book describes the horrors of war: “The wounded man’s face was no longer human. His lower jaw had been shot away entirely and one eye hung down his cheek. There was a sickly-sweet stench of blood and pus …”

Bertha von Suttner and Alfred Nobel

Bertha was born Countess Kinski von Chinic und Tettau, but her family lacked wealth. She took employment as governess for the family of Baron von Suttner in Vienna. Bertha fell in love with Arthur, the son of the house, but was forced to leave when the relationship was discovered. In 1876, she became Alfred Nobel’s secretary and housekeeper in Paris. However, she resigned after one week to elope with her beloved Arthur. She and Alfred Nobel developed a life-long friendship, corresponding frequently. There is little doubt that Bertha von Suttner played a major role in inspiring Alfred Nobel to establish the peace prize.

Nine years in the Caucasus

After their break with the von Suttner family in 1876, Bertha and Arthur settled in the Caucasus. She taught singing, music and language, and they both wrote articles for Western newspapers about conditions in the East. During this time Bertha made her debut as a novelist. She wrote several novels inspired by Darwin’s and Spencer’s theories of evolution and their optimism for the future. Returning to Paris in 1885, Bertha and Arthur sought intellectual circles. Bertha met her former employer Alfred Nobel, and she embraced the peace movement’s belief in arbitration as a means of preventing imminent war.

| Darwinism Name of the line of thinking developed by Charles Darwin (Great Britain) on the origin of the species. Life has evolved from simpler forms over billions of years, and only those species which have adapted best to changing conditions have survived. |

Peace is also about women’s rights!

Norwegian poet and peace activist Bjørnstjerne Bjørnson, a member of the Norwegian Nobel Committee, introduced Bertha von Suttner before her Nobel Lecture in 1906 by describing how she as a young woman in Austria had shown great courage in daring to shout, “Lay down your arms!” in a military state, despite being met with laughter and scorn. Bertha von Suttner began her career as an activist at a time when there was a general rise in the active participation of women in efforts to promote peace. The rights of women would not be achieved until the ideal of the warmongering male lost its sway, concluded Bjørnson.

Learn more

Disclaimer: Every effort has been made by the publisher to credit organisations and individuals with regard to the supply of photographs. Please notify the publishers regarding corrections.

Bertha von Suttner – Nominations

Bertha von Suttner – Photo gallery

Portrait of Bertha von Suttner, 1906. Photo: Carl Pietzner Source: Stadtchronik Wien, Verlag Christian Brandstädter, via Wikimedia Commons

Bertha von Suttner giving a lecture on peace and the women's movement, 1913. From left to right: Miss Rosa Manus, Mrs Baroness Sloet van Hagensdorp, Bertha von Suttner, Miss Dr. Mia Boissevain, Freule Backer, Miss L. C. A. van Eeghen and Mrs B. Midderigh-Bokhorst.

Photographer unknown. Overvoorde-Gordon, J. (Coauteur), Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

World Peace Congress in Munich 1907: Bertha von Suttner (seated row, second from left), Ludwig Quidde (next to the right), Frédéric Passy (next to the right), Henri La Fontaine (to her right) and A. H. Fried (standing row, third from the right).

Photographer unknown. Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

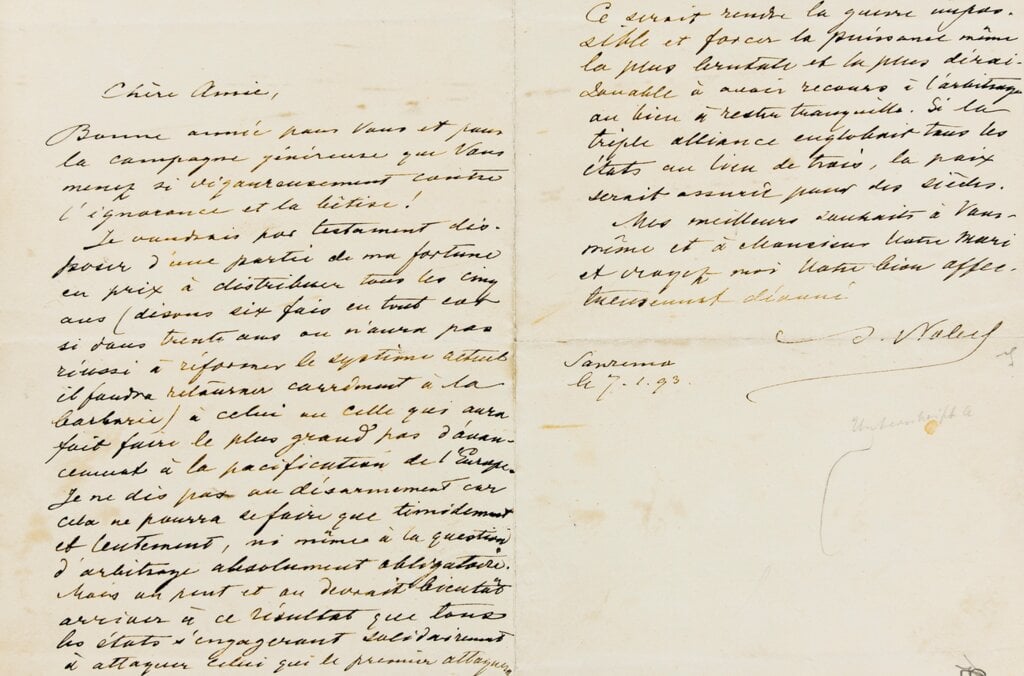

A letter from Alfred Nobel to Bertha von Suttner in 1893, where Alfred presents his first ideas regarding introducing a peace prize.

Source: World Digital Library at the Library of Congress.

Bertha von Suttner – Other resources

Links to other sites

‘Bertha Von Suttner: Who was she?’ at BBC

Bertha von Suttner Collected Papers, 1881-1995 at Swarthmore College

Bertha von Suttner – Nobel Lecture

English

German

Nobel Lecture*, April 18, 1906

(Translation)

The Evolution of the Peace Movement

The stars of eternal truth and right have always shone in the firmament of human understanding. The process of bringing them down to earth, remolding them into practical forms, imbuing them with vitality, and then making use of them, has been a long one.

One of the eternal truths is that happiness is created and developed in peace, and one of the eternal rights is the individual’s right to live. The strongest of all instincts, that of self-preservation, is an assertion of this right, affirmed and sanctified by the ancient commandment “Thou shalt not kill.”

It is unnecessary for me to point out how little this right and this commandment are respected in the present state of civilization. Up to the present time, the military organization of our society has been founded upon a denial of the possibility of peace, a contempt for the value of human life, and an acceptance of the urge to kill.

And because this has been so, as far back as world history records (and how short is the actual time, for what are a few thousand years?), most people believe that it must always remain so. That the world is ever changing and developing is still not generally recognized, since the knowledge of the laws of evolution, which control all life, whether in the geological timespan or in society, belongs to a recent period of scientific development.

It is erroneous to believe that the future will of necessity continue the trends of the past and the present. The past and present move away from us in the stream of time like the passing landscape of the riverbanks, as the vessel carrying mankind is borne inexorably by the current toward new shores.

That the future will always be one degree better than what is past and discarded is the conviction of those who understand the laws of evolution and try to assist their action. Only through the understanding and deliberate application of natural laws and forces, in the material domain as well as in the moral, will the technical devices and the social institutions be created which will make our lives easier, richer, and more noble. These things are called ideals as long as they exist in the realm of ideas; they stand as achievements of progress as soon as they are transformed into visible, living, and effective forms.

“If you keep me in touch with developments, and if I hear that the Peace Movement is moving along the road of practical activity, then I will help it on with money.”

These words were spoken by that eminent Scandinavian to whom I owe this opportunity of appearing before you today, Ladies and Gentlemen. Alfred Nobel said them when my husband and I visited with him in 1892 in Bern, where a peace congress1 was in progress.

His will showed that he had gradually become convinced that the movement had emerged from the fog of pious theories into the light of attainable and realistically envisaged goals. He recognized science and idealistic literature as pursuits which foster culture and help civilization. With these goals he ranked the objectives of the peace congresses: the attainment of international justice and the consequent reduction in the size of armies.

Alfred Nobel believed that social changes are brought about slowly, and sometimes by indirect means. He contributed 80,000 francs to Andrée’s attempt to cross the North Pole2. He wrote to me that this could contribute more to peace than I would believe. “If Andrée attains his goal, or even if he only half attains it, it will be one of those successes that stimulate a spate of talk and excitement which open the way for the generation and acceptance of new ideas and new reforms.”3

But Nobel also saw a shorter and more direct way before him. On another occasion he wrote4 to me: “It could and should soon come to pass that all states pledge themselves collectively to attack an aggressor. That would make war impossible, and would force even the most brutal and unreasonable Power to appeal to a court of arbitration, or else keep quiet. If the Triple Alliance included every state instead of only three, then peace would be assured for centuries.”

Alfred Nobel did not live to see the great progress and decisive events by which the Peace Idea was brought to life and made to function in a number of organizations.

He was, however, still alive in 1894 when Gladstone5, the great British statesman, went even further than the principle of arbitration in proposing a permanent international tribunal. Philip Stanhope6, a friend of the Grand Old Man, delivered this proposition to the Interparliamentary Conference of 1894 in Gladstone’s name and succeeded in having a plan for such a tribunal forwarded to the member governments. Alfred Nobel lived to see the forwarding, but it was only after his death that any results were achieved: the calling of the Hague Conference and the founding of the Permanent Court of Arbitration7. It was of incalculable damage to the [peace] movement that such men as Alfred Nobel, Moritz von Egidy8, and Johann von Bloch9 were taken from it prematurely. It is true that their ideals and their work continue beyond the grave, but had they still been living in our midst, how greatly would their personal influence and the effect of their work have contributed to the acceleration of the movement! With what courage would they have taken up the fight against the militarists who are at the present time trying to keep the shaky old system going!

That system is doomed to failure. Once a new system begins to emerge, the old ones must fall. The conviction that it is possible, that is necessary, and that it would be a blessing to have an assured judicial peace between nations is already deeply embedded in all social strata, even in those that wield the power. The task is already so clearly outlined, and so many are already working on it, that it must sooner or later be accomplished. A few years ago there was not a single minister of state professing the ideals of the peace movement. Today there are already many heads of state who do so. The first statesman in office to pledge his agreement to an interparliamentary conference officially, was, as I recall, Norwegian Prime Minister Steen10. It was John Lund11 who brought this news – which caused a sensation at the time – to the 1891 Interparliamentary Conference in Rome. Moreover, it was the Norwegian government which was the first to pay the traveling expenses of members of the Interparliamentary Union and to make a grant to the Peace Bureau in Bern12. Alfred Nobel had good reasons for choosing to entrust the administration of the funds of his peace legacy to the Norwegian Parliament.

Let us look round us in the world of today and see whether we are really justified in claiming for pacifism progressive development and positive results. A terrible war13, unprecedented in the world’s history, recently raged in the Far East. This war was followed by a revolution14, even more terrible, which shook the giant Russian empire, a revolution whose final outcome we cannot yet foresee. We hear continually of fire, robbery, bombings,. executions, overflowing prisons, beatings, and massacres; in short, an orgy of the Demon Violence. Meanwhile, in Central and Western Europe which narrowly escaped war, we have distrust, threats, saber rattling, press baiting, feverish naval buildup, and rearming everywhere. In England, Germany, and France, novels are appearing in which the plot of a future surprise attack by a neighbor is intended as a spur to even more fervent arming. Fortresses are being erected, submarines built, whole areas mined, airships tested for use in war; and all this with such zeal – as if to attack one’s neighbor were the most inevitable and important function of a state. Even the printed program of the second Hague Conference [to be held in 1907] proclaims it as virtually a council of war. Now in the face of all this, can people still maintain that the peace movement is making progress?

Well, we must not be blinded by the obvious; we must also look for the new growth pushing up from the ground below. We must understand that two philosophies, two eras of civilization, are wrestling with one another and that a vigorous new spirit is supplanting the blatant and threatening old. No longer weak and formless, this promising new life is already widely established and determined to survive. Quite apart from the peace movement, which is a symptom rather than a cause of actual change, there is taking place in the world a process of internationalization and unification. Factors contributing to the development of this process are technical inventions, improved communications, economic interdependence, and closer international relations. The instinct of self-preservation in human society, acting almost subconsciously, as do all drives in the human mind, is rebelling against the constantly refined methods of annihilation and against the destruction of humanity.

Complementing this subconscious striving toward an era free of war are people who are working deliberately toward this goal, who visualize the main essentials of a plan of action, who are seeking methods which will accomplish our aim as soon as possible. The present British prime minister, Campbell-Bannerman15, is reopening the question of disarmament. The French senator d’Estournelles 16 is working for a Franco-German entente. Jaurès17 summons the socialists of all countries to a united resistance to war. A Russian scholar, Novikov18, calls for a sevenfold alliance of confederated great powers of the world. Roosevelt offers arbitration treaties to all countries and speaks the following words in his message to Congress19: “It remains our clear duty to strive in every practicable way to bring nearer the time when the sword shall not be the arbiter among nations.”

I wish to dwell for a moment on the subject of America. This land of limitless opportunities is marked by its ability to carry out new and daring plans of enormous imagination and scope, while often using the simplest methods. In other words, it is a nation idealistic in its concepts and practical in its execution of them. We feel that the modern peace movement has every chance in America of attracting strong support and of finding a clear formula for the implementation of its aims. The words of the President just quoted reveal full understanding of the task. The methods are outlined in the following objectives, which comprise the program of a peace campaign currently being waged in America.

(1) Arbitration treaties.

(2) A peace union between nations.

(3) An international body with strength to maintain law between nations, as between the States of North America, and through which the need for recourse to war may be abolished.

When Roosevelt received me in the White House on October 17, 1904, he said to me, “World peace is coming, it certainly is coming, but only step by step.”

And so it is. However clearly envisaged, however apparently near and within reach the goal may be, the road to it must be traversed a step at a time, and countless obstacles surmounted on the way.

Furthermore, we are dealing with a goal as yet not perceived by many millions or, if perceived, regarded as a utopian dream. Also, powerful vested interests are involved, interests trying to maintain the old order and to prevent the goal’s being reached. The adherents of the old order have a powerful ally in the natural law of inertia inherent in humanity which is, as it were, a natural defense against change. Thus pacifism faces no easy struggle. This question of whether violence or law shall prevail between states is the most vital of the problems of our eventful era, and the most serious in its repercussions. The beneficial results of a secure world peace are almost inconceivable, but even more inconceivable are the consequences of the threatening world war which many misguided people are prepared to precipitate. The advocates of pacifism are well aware how meager are their resources of personal influence and power. They know that they are still few in number and weak in authority, but when they realistically consider themselves and the ideal they serve, they see themselves as the servants of the greatest of all causes. On the solution of this problem depends whether our Europe will become a showpiece of ruins and failure, or whether we can avoid this danger and so enter sooner the coming era of secure peace and law in which a civilization of unimagined glory will develop. The many aspects of this question are what the second Hague Conference should be discussing rather than the proposed topics concerning the laws and practices of war at sea, the bombardment of ports, towns, and villages, the laying of mines, and so on. The contents of this agenda demonstrate that, although the supporters of the existing structure of society, which accepts war, come to a peace conference prepared to modify the nature of war, they are basically trying to keep the present system intact. The advocates of pacifism, inside and outside the Conference, will, however, defend their objectives and press forward another step toward their goal – the goal which, to repeat Roosevelt’s words, affirms the duty of his government and of all governments “to bring nearer the time when the sword shall not be the arbiter among nations”.

* The laureate delivered this lecture in the Hals Brothers Concert Hall to a large audience. The Oslo Aftenposten of April 19, 1906, reports that the laureate, dressed in black, her voice husky with emotion, held her audience from the first; that she spoke concisely, using no contrived appeals, no gestures, no change of facial expression. The translation is based on the German text published in Les Prix Nobel en 1905.

1. The fourth World Peace Congress, August 22-27, 1892. The conversation between Nobel and the laureate on this occasion is reported in Memoirs of Bertha von Suttner, Vol.1, pp. 429; 435-439.

2. Salomon August Andrée (1854-1897), Swedish aeronautical engineer and explorer, lost while attempting the first exploration by balloon of the Arctic.

3. This quotation, as well as the story of Nobel’s connection with Andrée, is reported by Nicholas Halasz in Nobel: A Biography of Alfred Nobel (New York: Orion Press, 1959), pp. 257-258; 262-264.

4. Letter dated January 7, 1893, Paris; quoted in Memoirs of Bertha von Suttner, Vol. I, pp. 438-439.

5. William Ewart Gladstone (1808-1898), British prime minister (1868-1874; 1880-1885; 1886; 1892-1894).

6. Philip James Stanhope (1847-1923), member of House of Commons (1886-1892; 1893-1900), member of House of Lords after becoming Lord Weardale in 1905; president of two Interparliamentary Conferences (1890; 1906).

7. Commonly known as the Hague Tribunal, the Court was established by the first Hague Peace Conference (1899).

8. Christoph Moritz von Egidy (1847-1898), German officer and writer; forced to leave the army because of his pamphlet Ernste Gedanken which questioned some of the official dogmas of the established church; his broad concept of the Christian ideal involved taking a stand on all problems, including that of peace.

9. Jean de Bloch (1836-1902), Polish-born industrialist, author, and peace advocate;wrote The Future of War in Its Technical, Economic, and Political Relations (English tram., 1899) which contends that modern war will become too deadly to be risked.

10. Johannes Wilhelm Christian Steen (1827-1906), member of Norwegian Parliament for many years; prime minister (1891-1893; 1898-1902); member of the Norwegian Nobel Committee (1897-1904).

11. John Theodor Lund (1842-1913), member of Norwegian Parliament; member of the Norwegian Nobel Committee (1897-1913). At the banquet honoring the laureate, Mr.Lund proposed the toast to Sweden and the memory of Alfred Nobel.

12. The Interparliamentary Union (1889), composed of members from the various parliaments of the world, had at this time the primary objective of furthering the cause of international arbitration. The Permanent International Peace Bureau (1891), commonly called the Bern Bureau, was an information center for organizations and individuals working for peace and an executive arm for the international peace congresses.

13. The Russo- Japanese War (1904-1905).

14. The Revolution of 1905 in which dissatisfaction with czarist autocracy, spurred by losses in the war with Japan, resulted in a series of strikes, insurrections, and assassinations, along with demands for a constituent assembly; the atmosphere of revolution was still strong at the time of the laureate’s speech.

15. Sir Henry Campbell-Bannerman (1836-1908), British statesman of the Liberal Party; prime minister (1905-1908); advocate of international arbitration and armanient limitation.

16. Baron Paul Henri Benjamin Balluet d’Estournelles de Constant de Rebecque (1852-1924), co-recipient of the Peace Prize for 1909.

17. Jean Léon Jaurès (1859-1914), French politician; leader of the Socialists in the Chamber of Deputies; founder (with Aristide Briand) and editor of L’Humanité (1904-1914).

18. Yakov Aleksandrovich Novikov (1849-1912), Russian writer; author of La Fédération de l’Europe (1901).

19. President Theodore Roosevelt’s fifth annual message to the U.S. Congress, December 5, 1905.

The Nobel Foundation's copyright has expired.Bertha von Suttner – Nobelvorlesung

English

German

Vortrag, Gehalten vor dem Nobel-Comité des Storthing zu Christiania am l8. April 1906

Die Entwicklung der Friedensbewegung

Die ewigen Wahrheiten und ewigen Rechte haben stets am Himmel der menschlichen Erkenntnis aufgeleuchtet, aber nur gar langsam wurden sie von da herab geholt, in Formen gegossen, mit Leben gefüllt, in Taten umgesetzt.

Eine jener Wahrheiten ist die, dass Frieden die Grundlage und das Endziel des Glückes ist, und eines jener Rechte ist das Recht auf das eigene Leben. Der stärkste aller Triebe, der Selbsterhaltungstrieb, ist gleichsam eine Legitimation dieses Rechtes, und seine Anerkennung ist durch ein uraltes Gebot geheiligt, welches heisst: “Du sollst nicht töten”.

Doch wie wenig im gegenwärtigen Stande der menschlichen Kultur jenes Recht respektiert und jenes Gebot befolgt wird, das brauche ich nicht zu sagen. Auf Verleugnung der Friedensmöglichkeit, auf Geringschätzung des Lebens, auf den Zwang zum Töten ist bisher die ganze militärisch organisierte Gesellschaftsordnung aufgebaut.

Und weil es so ist und weil es so war, solange unsere – ach so kurze, was sind ein paar tausend Jahre? – sogenannte Weltgeschichte zurückreicht, so glauben manche, glauben die meisten, dass es immer so bleiben müsse. Dass die Welt sich ewig wandelt und entwickelt, ist eine noch gering verbreitete Erkenntnis, denn auch die Entdeckung des Evolutionsgesetzes, unter dessen Herrschaft alles Leben – das geologische wie das soziale – steht, gehört einer jungen Periode der Wissenschaftsentwicklung an.

Nein; der Glaube an den ewigen Bestand des Vergangenen und Gegenwärtigen ist ein irrtümlicher Glaube. Das Gewesene und Seiende flieht am Zeitstrome zurück wie die Landschaft des Ufers; und das auf dem Strom getragene mit der Menschheit befrachtete Schiff treibt unablässig den neuen Gestaden dessen zu, was wird.

Dass das Werdende, das Erzielte immer um einen Grad besser, höher, glücklicher sich gestaltet als das Gewesene, das Ueberwundene, das ist die Ueberzeugung derer, die das Entwicklungsgesetz erkannt haben und die an seiner Betätigung mit zu helfen sich bemühen. Erst durch die Erkenntnis und bewusste Benützung der Naturgesetze und Naturkräfte, sowohl auf physischem wie auf moralischem Gebiete, werden die technischen Erfindungen und die sozialen Einrichtungen geschaffen, welche unser Leben erleichtern, bereichern und veredeln. Ideale nennt man diese Dinge, solange sie noch im Reiche der Idee schweben, als erreichte Fortschritte stehen sie da, sobald sie in eine sichtbare, lebendige und wirkungskräftige Form gebracht worden sind.

“Wenn Sie mich auf dem Laufenden erhalten und ich erfahre, dass die Friedensbewegung den Weg der praktischen Betätigung einzuschlagen beginnt, dann will ich dabei mit pekuniären Mitteln weiterhelfen.”

Dies sind die Worte, die der edle Nordländer, dem ich die Ehre verdanke, vor Ihnen, meine Herren und Frauen, hier zu erscheinen – die Alfred Nobel im Jahre 1892 in Bern an mich richtete, als er dort, wo eben ein Friedenskongress tagte, mit uns, meinem Mann und mir, zusammentraf.

Dass Alfred Nobel sich allmählich überzeugt hat, dass die Bewegung aus dem Wolkengebiet der frommen Theorien auf dasjenige der erreichbaren und praktisch abgesteckten Ziele übergegangen ist, das hat er durch sein Testament bewiesen. Neben den anderen Dingen, die er als zur Förderung der Kultur dienend erkannt hat, nämlich die Wissenschaft und die idealistische Literatur, hat er auch die Ziele der Friedenskongresse, nämlich Erlangung internationaler Justiz und daraus folgend Herabminderung der Heere, angereiht.

Auch Alfred Nobel war der Ansicht, dass die sozialen Wandlungen sich nur langsam und mitunter auf indirekten Wegen vollziehen. Er hatte für die Nordpolexpedition Andrees 80,000 Frcs gespendet. Er schrieb mir darüber, dass dies der Friedenssache mehr nützen könne, als ich glaube.

“Wenn Andree sein Ziel erreicht, selbst wenn er es nur halb erreicht, so wird dies eines jener Lärm und Gärung verursachenden Erfolge sein, welche die Geister bewegen und das Entstehen und die Aufnahme neuer Ideen und neuer Reformen bewirken.”

Aber auch einen näheren und unmittelbareren Weg sah Nobel vor sich. Ein anderes Mal schrieb er mir:

“Man könnte und sollte bald zu dem Ergebnis gelangen, dass sich alle Staaten solidarisch verpflichten, denjenigen anzugreifen, der zuerst einen ändern angriffe. Das würde den Krieg unmöglich machen und müsste auch die brutalste und unvernünftigste Macht zwingen, sich an das Schiedsgericht zu wenden oder ruhig zu bleiben. Wenn der Dreibund alle, statt drei Staaten umfasste, so wäre der Friede auf Jahrhunderte gesichert.”

Alfred Nobel hat die grossen Fortschritte und die entscheidenden Ereignisse nicht mehr erlebt, durch welche die Friedensidee zu lebendigen Organen, d. h. funktionierenden Institutionen gelangt ist.

Im Jahre 1894 konnte er doch noch erfahren, dass der grosse englische Staatsmann Gladstone, noch über das Schiedsgerichtsprinzip hinaus, die Einsetzung eines ständigen Völkertribunals vorschlug. Ein Freund des grand old man, Philip Stanhope, hat der interparlamentarischen Konferenz von 1894 diesen Antrag im Namen Gladstones überbracht und erreicht, dass der Plan eines solchen Tribunals an die Regierungen versendet werde. Auch diese Versendung hat Alfred Nobel noch erlebt. Aber die Folgen davon: die Einberufung der Haager Konferenz und die Gründung des dortigen ständigen Schiedsgerichtshofes, die haben sich erst nach seinem Tode vollzogen. Es bleibt ein unberechenbarer Schaden für die Bewegung, dass ihr Männer, wie Alfred Nobel, Moritz v. Egidy und Johann v. Bloch, zu frühzeitig entrissen worden sind! Zwar wirken ihre Werke und Taten noch über das Grab fort, aber wären sie lebendig unter uns, wieviel würde ihr persönlicher Einfluss und ihre wirkende Kraft noch zur Beschleunigung der Bewegung beitragen. Wie tapfer würden sie den Kampf aufgenommen haben, der gerade jetzt von der Seite des Militarismus geführt wird, um das erschütterte alte System aufrecht zu erhalten.

Vergebens: alte Systeme müssen weichen, wenn ein neues einmal begonnen hat, sich zu organisieren. Die Ueberzeugung von der Möglichkeit, von der Notwendigkeit und von der Segensfülle eines gesicherten juridischen Friedenszustandes zwischen den Völkern ist schon zu sehr in alle Schichten, auch schon in die Machtsphären gedrungen, die Aufgabe ist schon zu klar hingestellt, und zu viele arbeiten schon daran, als dass sie nicht früher oder später erfüllt werden sollte. Heute sind die Staatsoberhäupter schon zahlreich, die sich zum Ideal der Friedensbewegung bekennen. Vor einigen Jahren war noch kein einziger Minister in ihren Reihen. Der erste an der Macht befindliche Staatsmann, von dem ich mich erinnere, dass er offiziell einer interparlamentarischen Konferenz seine Zustimmung mitteilen liess, war der norwegische Ministerpräsident Steen. John Lund war es, der diese Botschaft – die damals Aufsehen erregte – der im Jahre 1891 in Rom tagenden interparlamentarischen Konferenz überbrachte. Die norwegische Regierung war auch die erste, die den Mitgliedern der interparlamentarischen Union Reisespesen und dem Berner Friedensbureau eine Subvention bewilligte. Alfred Nobel wusste wohl, warum er die Verwaltung seines Friedenslegates gerade dem Storthing anvertraut hat.

Sehen wir uns doch ein wenig in der Welt um, ob die Ereignisse und Aspekte wirklich dazu berechtigen, von den positiven Ergebnissen des Pacificismus und von seiner fortschreitenden Entwicklung zu reden. Ein furchtbarer Krieg, wie ihn die Weltgeschichte noch nicht gesehen, hat eben im fernen Osten gewütet; eine noch furchtbarere Revolution knüpft sich daran, die das riesige russische Reich durchschüttert und deren Ende gar nicht abzusehen ist. Nichts als Brände, Raube, Bomben, Hinrichtungen, überfüllte Gefängnisse, Peitschungen und Massakres, kurz eine Orgie des Dämons Gewalt; im mittleren und westlichen Europa indessen kaum überstandene Kriegsgefahr, Misstrauen, Drohungen, Säbelgerassel, Presse-hetzen; fieberhaftes Flottenbauen und Rüsten überall; in England, Deutschland und Frankreich erscheinen Romane, in welchen der Zukunftsüberfall des Nachbars als ganz selbstverständlich Bevorstehendes geschildert wird mit der Absicht, dadurch zu noch heftigerem Rüsten anzuspornen; Festungen werden gebaut, Unterseeboote fabriziert, ganze Strecken unterminiert, kriegstüchtige Luftschiffe probiert, mit einem Eifer, als wäre das demnächstige Losschlagen die sicherste und wichtigste Angelegenheit der Staaten, und sogar die zweite Haager Konferenz wird mit einem Programm versehen, das sie zu einer Kriegskonferenz stempelt, und da wollen die Leute behaupten, die Friedensbewegung mache Fortschritte? …

Man muss eben nicht nur das Auffallende betrachten, das breit an der Oberfläche waltet, man muss auch das zu sehen verstehen, was aus dem Boden hervorspriesst; man muss verstehen, dass zwei Weltanschauungen und zwei Zivilisationsepochen jetzt mit einander ringen, und da wird man gewahr, dass mitten unter dem krachenden, drohenden Alten das verheissende Neue sich emporringt, gar nicht mehr vereinzelt, gar nicht mehr schwach und formlos, sondern schon viel verbreitet und lebenskräftig. Ganz unabhängig von der eigentlichen Friedensbewegung, die ja selber mehr ein Symptom als die Ursache der sich vollziehenden Wandlung ist, geht ein Prozess der Internationalisierung, der Solidarisierung der Welt vor sich. Dazu wirken mit: die technischen Erfindungen, der gesteigerte Verkehr, die sich verzweigenden und international durchdringenden Interessengemeinschaften, die gegenseitige wirtschaftliche Abhängigkeit, und halb unbewusst – wie Triebe schon sind – waltet da der Selbsterhaltungstrieb der menschlichen Gesellschaft, die ja auf dem Wege der ewig gesteigerten Vernichtungsmethode ihrer Zerstörung entgegenginge und sich instinktiv dagegen aufbäumt.

Neben diesen unbewussten Faktoren, die eine Aera der Kriegslosigkeit vorbereiten, gibt es die vollkommen Zielbewussten, welche den ganzen Aktionsplan schon in deutlichen Umrissen vor sich sehen, welche die Methode kennen und anzuwenden beginnen, durch die das vorgesteckte Ziel sobald als möglich erreicht werden kann. Der gegenwärtige englische Premier Campbell-Bannermann wirft von neuem die Abrüstungsfrage auf. Der französische Senator d’Estournelles will die französisch-deutsche Entente in die Wege leiten. Ein Jaures fordert die Sozialisten aller Länder zum einmütigen Widerstande gegen den Krieg auf. Ein russischer Gelehrter (Novikow) verlangt den Siebenbund der konföderierten Grosstaaten der Erde; ein Roosevelt bietet sämtlichen Staaten Schiedsgerichtsverträge an und spricht in seiner Botschaft an den Kongress folgende Worte:

“Es sei die Pflicht seiner Regierung, auf jede nur mögliche Weise die Zeit näher zu bringen, wo das Schwert nicht mehr Schiedsrichter zwischen den Völkern wäre.”

Bei Amerika möchte ich etwas verweilen. Das Land der unbeschränkten Möglichkeiten zeichnet sich dadurch aus, dass es die grössten und neuesten Pläne mit kühnem Geiste entwirft und zu deren Ausführungen die einfachsten und kürzesten Mittel aufzufinden versteht. Mit anderen Worten: ideal im Denken, praktisch im Tun. Die moderne Friedensbewegung wird – das steht uns in Aussicht – von Amerika aus einen kräftigen Anstoss und eine klare Formel der Verwirklichung finden. In den eben zitierten Worten des Präsidenten liegt die volle Erfassung der Aufgabe und in den nachfolgenden Sätzen, die einer gegenwärtig in Amerika betriebenen Friedenskampagne als Programm dienen, ist die Methode deutlich vorgezeichnet.

| 1. | Schiedsgerichtsverträge. |

| 2. | Eine Friedensunion zwischen den Staaten. |

| 3. | Eine internationale Institution, kraft deren das Recht zwischen den Völkern ausgeübt werden könnte, wie es zwischen unseren Staaten (von Nordamerika) ausgeübt wird und dadurch die Abschaffung der Notwendigkeit, zum Kriege Zuflucht zu nehmen. |

Als mich Roosevelt am 17. Oktober 1904 im weissen Hause empfing, sagte er zu mir: “Der Weltfriede kommt, er kommt gewiss, aber nur Schritt für Schritt.”

Und so ist es auch. So deutlich erkannt, so scheinbar naheliegend und leicht erreichbar ein Ziel auch winkt, der Weg dahin kann nur Schritt für Schritt zurückgelegt, und unzählige Hindernisse müssen dabei überwunden werden.

Und hier handelt es sich noch dazu um ein Ziel, das von vielen Millionen noch gar nicht gesehen wird, von dem unzählige Menschen entweder nichts wissen, oder das sie als eine Utopie betrachten. Mächtige Interessen sind auch damit verbunden, dass es nicht erreicht werde, dass alles beim Alten bleibe. Und die Anhänger des Alten, des Bestehenden, haben einen gar mächtigen Bundesgenossen an dem Naturgesetz der Trägheit, an dem Beharrungsvermögen, das allen Dingen innewohnt gleichsam als Schutz gegen die Gefahr des Vergehens. Es ist also kein leichter Kampf, der noch vor dem Pacificismus liegt. Von allen Kämpfen und Fragen, die unsere so bewegte Zeit erfüllen, ist diese Frage, ob Gewaltzustand oder Rechtszustand zwischen den Staaten, wohl die wichtigste und folgenschwerste. Denn ebenso unausdenkbar wie die glücklichen segensreichen Folgen eines gesicherten Weltfriedens, ebenso unausdenkbar furchtbar wären die Folgen des immer noch drohenden, von manchen Verblendeten herbeigewünschten Weltkrieges. Die Vertreter des Pacificismus sind sich wohl der Geringfügigkeit ihres persönlichen Machteinflusses bewusst, sie wissen, wie schwach sie noch an Zahl und Ansehen sind, aber wenn sie bescheiden von sich selber denken, von der Sache, der sie dienen, denken sie nicht bescheiden. Sie betrachten sie als die grösste, der über haupt: gedient werden kann. Von ihrer Lösung hängt es ab, ob unser Europa noch der Schauplatz von Ruin und Zusammenbruch werden, oder ob und wie in Verhütung dieser Gefahr noch früher die Aera des gesicherten Rechtsfriedens eingeführt werden soll, in der die Zivilisation zu ungeahnter Blüte sich entfalten wird. Das ist die Frage, die mit ihren vielseitigen Aspekten das Programm der zweiten Haager Konferenz füllen sollte, statt den vorgeschlagenen Erörterungen über die Gesetze und Gebräuche des Seekrieges, Beschiessung von Häfen, Städten und Dörfern, Legung von Minen u. s. w. Durch dieses Programm zeigt sich, wie die Anhänger der herrschenden Kriegsordnung diese letztere sogar noch auf dem eigensten Terrain der Friedensbewegung zwar modifizieren, aber aufrecht erhalten wollten. Die Anhänger des Pacificismus jedoch, innerhalb und ausserhalb der Konferenz, werden zur Stelle sein, um ihr Ziel zu verteidigen und sich ihm wieder einen Schritt zu nähern. Das Ziel nämlich, welches, um Roosevelts Worte zu wiederholen, die Pflicht seiner Regierung, die Pflicht aller Regierungen darstellt:

“Die Zeit herbeizuführen, wo der Schiedsrichter zwischen den Völkern nicht mehr das Schwert sein wird.”

The Nobel Foundation's copyright has expired.The Nobel Peace Prize 1905 – Introduction

Introduction by Bjørnstjerne Bjørnson, Member of the Nobel Committee, on April 18, 1906*

On behalf of the Nobel Committee, Bjørnstjerne Bjørnson introduced the speaker, Baroness Bertha von Suttner, to the audience. In a few words he recalled the great influence of the Baroness on the growth of the peace movement. While still young she had had the audacity to oppose the horrors of war1, and had done so in one of the most militaristic countries in Europe. She had continued this fight all her life and never wearied of crying “Down with Arms“2. Despite the laughter with which her words had been greeted in the beginning, they did receive a hearing because they were uttered by a person of noble character and because they proclaimed humanity’s greatest cause. Many women had since followed in her footsteps and taken up the cause, and the call to lay down arms had become general. Moreover, to all men of goodwill the cause of peace and the women’s cause were one and the same movement, striving for the same goal. When the cause of peace prevailed, then too would the women’s cause be won.

* Mr. Bjørnson, a leading writer and a friend of the laureate, introduced Baroness von Suttner when she delivered her Nobel address on April 18, 1906. This translation of his introduction is based on the Norwegian précis of it in the Oslo Aftenposten of April 19. It is given here because no presentation speech was made on December 10, 1905. This date, the one prescribed for announcing the award; fell on a Sunday when the Norwegian Parliament was not in session. In order to conform to the Statute, the Committee invited Parliament members to attend the inauguration of the new Norwegian Nobel Institute building, which took place on that day, and made its announcement there. Speeches or remarks on this occasion were devoted to Alfred Nobel, the Nobel Foundation, etc. The Committee’s decision was also given officially to the Parliament at its session the next day, December 11. Baroness von Suttner was unable to be present at either ceremony because of fatigue incurred during a strenuous schedule of meetings and speaking engagements. A speech in honor of Baroness von Suttner given by Mr. Løvland at the banquet after her address is also included here.

1. The laureate describes herself as being, in her earlier years, either “piously loyal to the military” or completely unconcerned about the horrors of war. See her Memoirs, Vol. 1, pp. 46; 70-73; 133-136; 173-174; 229-233.

2. Lay Down Your Arms is the English title of the laureate’s famous novel against war.

* * *

Speech by Jørgen Gunnarsson Løvland, Chairman of the Nobel Committee, on April 18, 1906*

History constantly demonstrates the great influence of women. Women have encouraged the ideas of war, the attitude to life, and the causes for which men have fought, for which their sons were brought up, and of which they have dreamed. Any change or reformation of these ideas must be brought about chiefly by women. The human ideal of manly courage and manly deeds must become more enlightened; the faithful worker in all spiritual and material spheres of life must displace the bloodstained hero as the true ideal. Women will cooperate to give men higher aims, to give their sons nobler dreams.

Many are the individual women who have set an example in sacrifice and work, who have followed the armies as angels of consolation and healing, tending the sick and suffering. How much more effective it is to do one’s utmost to prevent misfortune!

This is where you, Madame Baroness, have taken the lead among women of today. You have attacked war itself and cried to the nations: “Down with arms!” This call will be your eternal honor.

Beginning as a murmur in the corn on a summer’s day

And growing to a gale through the tops of the forest,

Till the ocean bears it on with tenderous voice,

And nothing is heard but this.1

These stirring words of our great poet apply to your call to action, Madame Baroness. It began as a murmur through the lovely meadow of the Danube Valley2 , that old highway for the devastating armies of war. We already hear it in the forests in all parts of the world and soon, we hope, its voice, borne by the oceans of people, will permanently drown the sound of war drums and trumpets.

This will take a long time, some will say. We do not know. And it makes no difference to our work. Our task is clear: to combat any act of violence, any war of aggression, and so render even the justifiable defensive war unnecessary. We shall rouse the conscience of man, put justice and morality in the place of war.

We thank you, Madame Baroness, for your firm faith, for your hope and self-sacrifice, for your work. We too, in the lands of the North, women as well as men, need you to light and nourish the flame of faith and work. Good luck to you!

Frédèric Passy, that venerable apostle of peace3 has called you, Madame Baroness, our general-in-chief. The friends of peace in Scandinavia applaud this salute.

* Mr. Løvland, also at this time Norwegian foreign minister, delivered this speech in German at a banquet which he and his wife gave in honor of Baroness von Suttner after her Nobel address on April 18, 1906. The translation is based on the German text appearing in the Oslo Aftenposten the next day.

1. From a poem by the Norwegian poet Bjørnstjerne Bjørnson (1832-1910), recipient of the Nobel Prize in Literature for 1903, and the person who had introduced the laureate earlier in the day.

2. The laureate’s novel, Lay Down Your Arms, was written in the country near Vienna.

3. Frédéric Passy (1822-1912), co-recipient of the Nobel Peace Prize for 1901.

The Nobel Peace Prize 1905

Bertha von Suttner – Biographical

Baroness Bertha Felicie Sophie von Suttner (June 9, 1843-June 21, 1914), born Countess Kinsky in Prague, was the posthumous daughter of a field marshal and the granddaughter, on her mother’s side, of a cavalry captain. Raised by her mother under the aegis of a guardian who was a member of the Austrian court, she was the product of an aristocratic society whose militaristic traditions she accepted without question for the first half of her life and vigorously opposed for the last half.

As a girl and young adult, Bertha studied languages and music (at one time aspiring to an operatic career), read voraciously, and enjoyed an active social life enlivened by travel.

At thirty, feeling she could no longer impose on her mother’s dwindling funds, she took a position in Vienna as teacher-companion to the four daughters of the Suttner household. Here she met her future husband, the youngest son of the family. In 1876 she left for Paris to become Alfred Nobel‘s secretary but returned, after only a brief stay, to marry Baron Arthur Gundaccar von Suttner. Because of the Suttners’ strong disapproval of the marriage, the young couple left immediately for the Caucasus where for nine years they earned an often precarious living by giving lessons in languages and music and eventually, and more successfully, by writing.

During this period the Baroness produced Es Löwos, a poetic description of their life together; four novels; and her first serious book, Inventarium einer Seele [Inventory of a Soul], in which she took stock of her thoughts and ideas on what she and her husband had been reading together, especially in evolutionist authors such as Darwin and Spencer; included is the concept of a society that would achieve progress though achieving peace.

In 1885, welcomed by the Baron’s now relenting family, the Suttners returned to Austria where Bertha von Suttner wrote most of her books, including her many novels. Their life was oriented almost solely toward the literary until, through a friend, they learned about the International Arbitration and Peace Association1 in London and about similar groups on the Continent, organizations that had as an actual working objective what they had now both accepted as an ideal: arbitration and peace in place of armed force. Baroness von Suttner immediately added material on this to her second serious book, Das Maschinenzeitalter [The Machine Age] which, when published early in 1889, was much discussed and reviewed. This book, criticizing many aspects of the times, was among the first to foretell the results of exaggerated nationalism and armaments.

Wanting to «be of service to the Peace League… [by writing] a book which should propagate its ideas»2, Bertha von Suttner went to work at once on a novel whose heroine suffers all the horrors of war; the wars involved were those of the author’s own day on which she did careful research. The effect of Die Waffen nieder [Lay Down Your Arms], published late in 1889, was consequently so real and the implied indictment of militarism so telling that the impact made on the reading public was tremendous. And from this time on, its author became an active leader in the peace movement, devoting a great part of her time, her energy, and her writing to the cause of peace – attending peace meetings and international congresses, helping to establish peace groups, recruiting members, lecturing, corresponding with people all over the world to promote peace projects.

In 1891 she helped form a Venetian peace group, initiated the Austrian Peace Society of which she was for a long time the president, attended her first international peace congress, and started the fund needed to establish the Bern Peace Bureau.

In 1892, with A. H. Fried, she initiated the peace journal Die Waffen Nieder, remaining its editor until the end of 1899 when it was replaced by the Friedenswarte (edited by Fried) to which she regularly contributed comments on current events (Randglossen zur Zeitgeschichte) until she died. Also in 1892 she promised Alfred Nobel to keep him informed on the progress of the peace movement and, if possible, to convince him of its effectiveness. No doubt she felt that she was beginning to succeed when she received a letter from him in January of 1893, telling her about a peace prize he hoped to found, one which, after his death in 1896, his will showed he had indeed established 3.

Bertha von Suttner, along with her husband, worked hard to gain support for the Czar’s Manifesto and the Hague Peace Conference of 1899, arranging public meetings, forming committees, lecturing. She sent accounts of the Conference itself to the Neue Freie Presse and to other papers, in other countries, and in the following year wrote articles and initiated meetings to popularize the idea of the Permanent Court of Arbitration set up by the Conference.

Although grief-stricken after her husband’s death in 1902, she determined to carry on the work which they had so often done together and which he had asked her to continue.

She now left her quiet retirement in Vienna only on peace missions, which often included arduous speaking tours. She continued to write, but only for the cause of peace. By 1905 when she received the Nobel Peace Prize – at a fortuitous time financially – she was widely thought of as sharing the leadership of the peace movement with the venerable Passy. In the years that followed she played a prominent part in the Anglo-German Friendship Committee formed at the 1905 Peace Congress to further Anglo-German conciliation; she warned all who would listen about the dangers of militarizing China and of using the rapidly developing aviation as a military instrument; she contributed lectures, articles, and interviews to the International Club set up at the 1907 Hague Peace Conference to promote the movement’s objectives among the Conference delegates and the general public; she spoke at the 1908 Peace Congress in London; and she repeated again and again that «Europe is one» and that uniting it was the only way to prevent the world catastrophe which seemed to be coming.

Her last major effort, made in 1912 when she was almost seventy, was a second lecture tour in the United States, the first having followed her attending the International Peace Congress of 1904 in Boston.

In August of 1913, already affected by beginning illness, the Baroness spoke at the International Peace Congress at The Hague where she was greatly honored as the «generalissimo» of the peace movement. In May of 1914 she was still able to take an interest in preparations being made for the twenty-first Peace Congress, planned for Vienna in September. But her illness – suspected cancer – developed rapidly thereafter, and she died on June 21, 1914, two months before the erupting of the world war she had warned and struggled against.

In accordance with her wishes, she was cremated at Gotha and her ashes left there in the columbarium. The war and its immediate aftermath put an end not only to the plans of the peace movement for the congress in Vienna but to its plans for a monument to Bertha von Suttner.

| Selected Bibliography |

| Abrams, Irwin, «Bertha von Suttner and the Nobel Peace Prize», in Joumal of Central European Affairs, Vol. 22, No. 3 (October, 1962), 286-307. |

| Kempf, Beatrix, Bertha von Suttner: Das Lebensbild einer grossen Frau. Wien, Österreichischer Bundesverlag, 1964. |

| Playne, Caroline E., Bertha von Suttner and the Struggle to Avert the World War. London, Allen & Unwin, 1936. |

| Suttner, Bertha von. Most papers and manuscripts are in the Bertha von Suttner Manuscript Collection in the Peace Archives of the United Nations Library in Geneva, Switzerland. The Nobel Archives of the Nobel Foundation in Stockholm, Sweden, contain communications from Baroness von Suttner to Alfred Nobel. |

| Suttner, Bertha von, Bertha von Suttners gesammelte Schriften in 12 Bdn. Dresden, E. Pierson, 1906. |

| Suttner, Bertha von, Briefe an einen Toten. Dresden, E. Pierson, 1904, 1905. |

| Suttner, Bertha von, Inventarium einer Seele. Leipzig, W. Friedrich, 1883. |

| Suttner, Bertha von, Der Kampf um die Vermeidung des Weltkrieges: Randglossen aus zwei Jahrzehnten zu den Zeitereignissen vor der Katastrophe (1892-1900 und 1907-1914). 2 Bde. Zürich, Orell Füssli, 1917. |

| Suttner, Bertha von, Krieg und Frieden: Ein Vortrag. München, A. Schupp, 1900. |

| Suttner, Bertha von, Lay Down Your Arms: The Autobiography of Martha von Tilling. Authorized translation [of Die Waffen nieder]. London, Longmans, 1892. |

| Suttner, Bertha von, Marthas Kinder. Fortsetzung zu Die Waffen nieder. Dresden, E. Pierson, 1902. |

| Suttner, Bertha von, Das Maschinenzeitalter. Zukunftsvorlesungen über unsere Zeit von «Jemand». Zürich, Verlags-Magazin, 1891. |

| Suttner, Bertha von, Memoirs of Bertha von Suttner: The Records of an Eventful Life. Authorized translation [of the Memoiren]. 2 vols. Boston, Ginn, 1910. |

1. Founded in 1880 by Hodgson Pratt (1824-1907), English pacifist.

2. Memoirs of Bertha von Suttner, Vol. I, p. 294.

3. For a detailed account of the relationship between Alfred Nobel and Bertha von Suttner and a discussion of the Peace Prize itself, including Baroness von Suttner’s reactions and opinions concerning it, see Irwin Abrams’ article «Bertha von Suttner and the Nobel Peace Prize».

This autobiography/biography was written at the time of the award and first published in the book series Les Prix Nobel. It was later edited and republished in Nobel Lectures. To cite this document, always state the source as shown above.

The Nobel Foundation's copyright has expired.