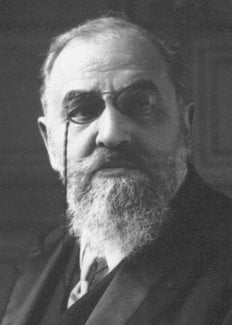

Léon Victor Auguste Bourgeois (May 21, 1851-September 29, 1925), the «spiritual father» of the League of Nations, was a man of prodigious capabilities and diversified interests …

Léon Bourgeois – Speed read

Léon Bourgeois was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize for his longstanding contribution to the cause of peace and justice and his prominent role in the establishment of the League of Nations.

Full name: Léon Victor Auguste Bourgeois

Born: 21 May 1851, Paris, France

Died: 29 September 1925, Épernay, France

Date awarded: 10 December 1920

An internationalist

Léon Bourgeois served as prefect of police in Paris and French prime minister before devoting himself to international peace efforts at the Hague Peace Conferences of 1899 and 1907. He optimistically maintained that reason and science would make the world a better place. Bourgeois believed that conflicts between states should be resolved through arbitration in a permanent international court of salaried judges. During WWI, Bourgeois proposed the creation of an association of states to safeguard world peace. His plan conferred greater supranational authority on the organisation than US President Woodrow Wilson’s model. Although Wilson’s philosophy dominated the 1919 League of Nations, Bourgeois did win approval for the founding of an international court at The Hague, Netherlands.

“And the (…) Peace Prize, awarded to Léon Bourgeois, was ushered in with a salute from Norway to the will for peace of the French people, whom he has represented with great distinction for many years through good days and bad.”

Anders Johnsen Buen, Remarks at the award ceremony, 10 December 1920.

Bourgeois’s league of states

During WWI, Bourgeois presented his ideas on a new league of states. His proposal would make arbitration compulsory for states in conflict and create an international military force to be deployed as a last resort against states that violated international agreements. He also called for close inspections to monitor compliance with disarmament agreements. Bourgeois’s plan was not adopted, as most heads of state were not willing to relinquish so much power to a supranational authority.

“In the view of many historians, Bourgeois’s notions of international law and his concept of a League of Nations were at once more visionary and more realistic than those of his contemporaries.”

Wilson Biographical Dictionary, page 130, The Nobel Prize Winners, New York 1988.

The Nobel Peace Prize to Bourgeois

The decision to award the 1920 peace prize to Bourgeois was a long time in the making. Although he had been nominated over the years by many former laureates, he was deemed worthy of the prize only after he became president of the League of Nations in 1920. The news of Bourgeois’s selection was not well received in his home country. Those on the right held him responsible for a weak French military defence prior to WWI, and those on the left feared the League of Nations would be used against socialists and communists.

“The rise of man from the animal to the human level was prolonged by the necessity of rising from a state of barbarism and violence to one of order and peace.”

Léon Bourgeois, Communication to the Nobel Committee, December 1922.

Learn more

Disclaimer: Every effort has been made by the publisher to credit organisations and individuals with regard to the supply of photographs. Please notify the publishers regarding corrections.

Léon Bourgeois – Nobel Lecture

English

French

Communication to the Nobel Committee*, December, 1922

The Reasons for the League of Nations

Some weeks ago, Mr. Branting1 went to Oslo to fulfill the obligation incumbent upon every Nobel Peace Prize laureate. I wish to offer my apologies for not having been able to do the same this last year. The state of my health has not permitted me to make the journey to Norway, and this has caused me the most profound regret.

Your Chairman informed me that you would permit me to address you in writing. I now send you my sincere gratitude and an account of certain ideas of mine, which I would much prefer to have offered you in person. Gentlemen, please accept my heartfelt thanks.

I

I am in full agreement with the views Mr. Branting expressed to you last June. With great perspicacity, he analyzed and placed in proper perspective “the great disillusionment” which the Great War of 1914-1918 had engendered in the minds of men. Certainly, this sudden unleashing of a cataclysm unequalled in the past, appeared to be the direct negation of the hopes which Nobel had nurtured when he founded the Peace Prize. But in place of the discouragement which had taken hold of the public, Mr. Branting offered reasons for believing that we could still derive confidence from the catastrophe. He showed that, under the ruins left behind by the bitter times we have just experienced, there were to be found far too many signs of rejuvenation to allow us to discount the present years as a period of regression.

The victory had been, above all, a victory for law and order, and for civilization itself. The collapse of three great monarchies based largely upon military power had given birth to a number of young nations, each representing the right of peoples to govern themselves, as well as to enjoy the benefits of democratic institutions which, by making peace dependent on the will of the citizens themselves, infinitely reduced the risk of conflict in the future.

The same movement had brought not only the resurrection of oppressed nations, but also the reintegration in political unity of races hitherto torn apart by violence.

Finally, one singularly important fact had succeeded in giving true significance to the victory of free nations. Out of the horror of four years of war had emerged, like a supreme protest, a new idea which was implanting itself in the minds of all people: that of the necessity for civilized nations to join together for the defense of law and order and the maintenance of peace. The League of Nations, heralded in 1899 and 1907 by the Hague Peace Conferences, became, through the Covenant2 of June 28, 1919, a living reality.

But, can it furnish us at last with a stable instrument of peace? Or shall we again encounter, at the very moment when we think we are reaching our goal, the same obstacles which for centuries have blocked the way of those pilgrims of every race, creed, and civilization who have struggled in vain toward the ideal of peace?

II

To answer this question, which touches upon all the anguish of the human race, and to understand the causes of the upheavals which have beset mankind, we must delve not only into the history of peoples but into that of man himself, into the history of the individual, whose passions are no different from those of his community and in whom we are certain to find all propensities, good or bad, enlarged as in a mirror.

Human passions, like the forces of nature, are eternal; it is not a matter of denying their existence, but of assessing them and understanding them. Like the forces of nature, they can be subjected to man’s deliberate act of will and be made to work in harmony with reason. We see them at work in the strife between nations just as we see them in struggles between individuals, and we realize at last that only by using the means for controlling the latter can we control the former.

To assert that it is possible to establish peace between men of different nations is simply to assert that man, whatever his ethnical background, his race, religious beliefs, or philosophy, is capable of reason. Two forces within the individual contribute to the development of his conscience and of his morality: reason and sensitivity.

His sensitivity is twofold. At first, it is merely an expression of the instinct of self-preservation, springing from the need of all beings to develop at the expense of their surroundings, to the detriment of other beings whose death seems essential to their very existence. But there is also another manifestation of the instinct, which makes him sensitive to the suffering of others: it is this which creates a moral bond between mother and child, then between father and son, and later still between men of the same tribe, the same clan. It is this instinct of sympathy which enables man to fight against and to control his brutish and selfish instincts.

A great French philosopher, criticizing the doctrine according to which “one could wish no more for a race than that it should attain the fullest development of its strength and of its capacity for power”, has pointed out that this is only an incomplete concept of what man is. “This is to place man in isolation and to see in him a noble animal, mighty and formidable. But to be seen as a complete whole, man must be viewed in the society which developed him: The superior race is the one best adapted to society and to communal progress.”

In this respect, goodness, the need for sociability, and, to a higher degree, a sense of honor, are spontaneous attributes, valuable beyond all other instincts but just as natural. Now these feelings are present in a national community just as they are in the individuals who compose it. To place them above the gratification of individual egotism is the task of civilization. Never should the power of an individual be allowed to impede the progress of the rest of the nation; never should the power of a nation be allowed to impede the progress of mankind.

Man has a sensitivity which can be either selfish or altruistic; but it is reason which is his essence. It is not his violent and contradictory impulses, but rather his reason which, at first hesitant and fragile in childhood, then growing in strength, finally brings man to reconcile the two sides of his sensitivity in conscious and lasting harmony. It is reason which, from the beginning of history, has led mankind little by little in the course of successive civilizations to realize that there is a state preferable to that of the brutal struggle for life, not only a less dangerous state, but the only one capable of conforming to the dictates of conscience; and that is, in its ever increasing complexity and solidity, the truly social state.

The rise of man from the animal to the human level was prolonged by the necessity of rising from a state of barbarism and violence to one of order and peace. In this process too, it was reason that finally persuaded man to define, under the name of law, some limits within which each individual must confine himself if he wishes to be worthy of remaining in the social state.

At first, laws evolved out of religious doctrines. It followed that they were recognized only when advantageous to those who practiced the same religion and who appeared equals under the protection of the same gods. For the members of all other cults, there was neither law nor mercy. This was the age of implacable deities, of Baal and of Moloch; it was also the age of Jehovah, preaching to his people the extermination of the conquered.

The torch of reason was first held up to the world by Greek philosophy, which led to the stoicism according to which all men are equal and “are the members of a single body”, and in which the human will, regulated by law, is regarded as the guiding mechanism of man’s activity.

This doctrine of the human will was expressed in Roman law of the Imperial Age by that admirable theory of obligations which, in private law, makes the validity of contracts dependent upon the free consent of the contractors.

What a gulf there still exists between these affirmations of private law and the recognition of the same law as the guiding force for the policies of nations!

Then came Christianity which gave to man’s natural capacity for sympathy a form and a forcefulness hitherto unknown. The doctrine of Christ enjoins men, all brothers in His eyes, to love one another. It condemns violence, saying: “He who lives by the sword shall die by the sword.”3It preaches a Christian communion superseding all nationalities and offering to the Gentiles – in other words, to all nations of the earth – the hope of a better life in which justice will finally rule.

The Middle Ages, on the whole, embodied the history of the development of this doctrine, and for several centuries the efforts of the Papacy reflected a persistent desire to bring to the world, if not justice itself, which seemed still to be beyond the human grasp and which was generally left “in the hands of God”, at least a temporary, relative state of peace, “the Truce of God”4, which gave unhappy humanity a respite from its suffering, a brief moment of security.

But a new period of conflict arrived in its turn to upset Europe with religious wars5. These were perhaps the more. cruel because they obliged the conscience itself to repudiate compassion and seemed to incite conflict between the two forces which had hitherto shared the world between them: sensitivity and reason. Not until the eighteenth century were they finally reconciled.

The Declaration of the Rights of Man6 at last set down for all of mankind the principles of justice without which it would never be possible to lay any foundations for true and lasting peace.

But how much suffering, how much blood had to be squandered for more than a century before we could finally hope to see the application of the truly humanitarian, moral principles proclaimed by the French Revolution! It has been necessary, as Taine7 says, “to multiply ideas, to establish earlier thinking in the conscious mind, to marshal thoughts around accepted precepts: in a word, to reshape, on the basis of experience, the interior of the human head”.

Was not the greatest revolution in history that which allowed reason to regard the whole of humanity as being subject to law and to acknowledge the status of “man” in every human being?

All men equal in rights and duties, all men equally responsible for the destiny of mankind – what a dream!

Will the concept of law as mistress of the world finally make reason reasonable?

III

Have we arrived at a stage in the development of universal morality and of civilization that will allow us to regard a League of Nations as viable? If its existence is feasible, what characteristics and what limitations should it have in order to adapt itself to the actual state of affairs in the world?

Certainly, immense progress has already been made in the political, social, and moral organization of most nations.

The spreading of public education to nearly every corner of the globe is producing a powerful effect on many minds.

The prevalence of democratic institutions is evident in every civilized nation.

We are witnessing a weakening of the class prejudice so obstructive to social progress and we see, even in Russia, a rejection of Communist systems that seek to stifle personal liberty and initiative.

Finally, there is an increasing number of social institutions offering assistance, insurance, and fellowship, whose object is the protection of the rights of the individual and, in a broader sense, the propagation of the concept of an increasingly humanitarian justice under which the individual’s responsibility for his conduct will no longer be dissociated from that of society itself.

In every nation, all these factors are preparing the way for the intellectual revolution of which we speak, a revolution that will lead people to appreciate and to understand the superiority, indeed the absolute necessity, of having international organizations which will recognize and apply the same principles.

It is true, of course, that there still remain outside the movement to bring civilization to this superior state of conscience, vast territories whose populations, held for centuries in slavery or servitude, have not yet felt the stir of this awakening influence and for whom a period, and undoubtedly a long one at that, of moral and intellectual growth is imperative.

Nevertheless, it is a new and significant fact that the civilized nations, alert to “the sacred trust of civilization”, have, within the terms of Article 22 of the Covenant of the League of Nations, undertaken the task of educating the backward peoples so that they may become “able to stand by themselves under the strenuous conditions of the modern world”.

Progress has been made not only in terms of institutions, organizations, and customs, but also in a purely political way from the standpoint of the map of Europe and of the world itself.

When the Hague Peace Conference of 1899, meeting at the instigation of the Czar, set before the civilized world the problem of disarmament and of peace, and for the first time mentioned the name “League of Nations”, it was a priori certain that the problem could not be solved at that time. The political geography of Europe was far too firmly founded on violations of the rights of peoples. How could anyone use it as a basis for organizing peace in the face of this fact?

Today, war has served to eliminate most of the injustices of that time. In Europe, Alsace-Lorraine has been returned to France; Poland has been restored as an independent entity; and the Czechoslovaks, Danes, Belgians, Slavs, and Latins have regained their respective rights of self-government or have been returned to their homelands.

Even in Asia a great effort is being made right now to find, in legality and in peace, a durable balance between the historic rights of the various races.

Does this mean, then, that in Europe or, for that matter, in other parts of the world all sources of trouble have disappeared? We are far from being blindly confident of the future; indeed, we have before our very eyes signs of trouble too obvious and too certain for us even to dream of denying them.

In the first place, certain powers that were defeated in the Great War have not been wholehearted in their acceptance of the moral disarmament which is the primary condition for any peace. Some turbulent minorities of uncertain character, too weak to form a state of their own but resistant to the majority in the societies of which they are a part, are seeking support outside the natural frontiers within which communal life thrives, thus threatening to create areas of friction and violence where there should be mutual tolerance and trust.

In the second place, artificial movements are springing up which seek to cross national boundaries, and to bring together in inorganic bodies the most varied of peoples. Movements such as the Pan-Germanic, Pan-Islamic, or Pan-Negro justify themselves on the basis of their common language,.or their common religion, or their color. But since the undefined masses involved in these movements lack the essential and real unity of background or community of purpose, they become a grave danger to general peace.

Yet all this may be of transient significance, for it seems to be mainly part of the last tremors of the cataclysm that has shaken the world.

But there is something more profound that must be taken into account about any international organization. Mr. Branting, in his speech to you a few months ago, showed that there was a world of difference between the International of the classes as envisaged by certain Socialist congresses and the true International of nations, and that only through the latter could peace be truly established among men, instead of being merely longed for against all reasonable hope.

The concept of patriotism is not incompatible with that of humanity; on the contrary, let me state emphatically that he who best serves pacifism, serves patriotism best. The nation is and can be no more than the vital basic unit of any international league. Just as the formation of the family is basic to the formation of the state, so the states themselves are the only units that can form the basic constitution of a viable international organization.

The 1914-1918 War, being a war of liberation of nationalities, could not help overstimulating nationalistic sentiment. It gave greater impetus to the moral and intellectual tendencies conducive to patriotism; it made this feeling, as well-founded as any other, more zealous. As a result, the proposed international organization must, in the final analysis, be based not only on the intangible sovereignty of each nation, but also on the equality of rights of them all, regardless of their strength, weakness, or relative size. It is only among properly constituted states that the reign of law and order can be established.

For these same reasons, it was impossible even to dream of any organization being forced on the nations from without. The idea of a “superstate” whose will could be imposed on the governing bodies of each nation might have brought about a revolt of patriotism. What was and is necessary and at the same time sufficient, is that each nation understand that mutual consent to certain principles of law and to certain agreements, acknowledged to be equally profitable to the contracting parties, no more implies a surrender of sovereignty than a contract in private business implies a renunciation of personal liberty. It is, rather, the deliberate use of this very liberty itself and an acknowledged advantage for both parties. But what, then, is the fundamental condition necessary for such an agreement, what is the indispensable condition that insures consent without reservation, that gives confidence to all sides that nothing essential, no vital interest, will be sacrificed by any of the contracting parties?

There must be a paramount rule, a sovereign standard, by which each settlement may be measured and checked, just as in the scientific world, man, distrusting his own fallible senses, refers for comparison and evaluation of phenomena to the evidence of standardized instruments free of personal error.

On a moral plane it is law, devoid of individual or national bias and immune to the fluctuations of opinion which will be the instrument, the unprejudiced registrar of claims and counterclaims. By its absolute impartiality and its authoritative evidence, the law will appease passions, disarm ill will, discourage illusory ambitions, and create that climate of confidence and calm in which the delicate flower of peace can live and grow.

Does such a sovereign and unassailable law in fact exist? The history of the past centuries suggests an affirmative answer.

Now and henceforth there exists an international law whose doctrine is firm and whose jurisprudence is not contested by a single civilized nation. The nineteenth century, which introduced the Hague Peace Conferences and generated numerous international conferences on a variety of subjects, also brought an increasing number of applications of international law. If this law was all too obviously violated in 1914 and during the war years, the victory has righted the wrong done. Should such violations ever happen again, then indeed we must despair of the future of mankind.

Of a purely theoretical and doctrinal nature at first, international law is gradually being enriched by numerous conventions containing essential obligations of a judicial order, which can be precisely defined and codified and made legally binding and subject to sanctions. The scope of these conventions grows continuously, gradually embracing moral concepts which constitute what I have called in a recent study, international ethics; it concerns everything that touches on the life, the health, and the well-being, material and spiritual, of all human beings.

International law does in fact exist.

But, can we hope that a juridical body vested with such sovereignty will ever constitute a faithful interpreter of the law as unbiased and dispassionate as the law itself?

The recent course of the deliberations in the League of Nations and the creation of the Court of International Justice8 enable us to say yes once again !

IV

Let us summarize the three conditions necessarily basic to any international organization which would be in step with contemporary civilization.

In the first place, there must exist among the associated states a community of thought and feeling and a development of ideas which, if not actually identical, should at least be sufficiently analogous to allow a common understanding of the principles of international order and to produce general agreement on the laws which give them effectiveness.

Second, each one of these laws must have received the free and unqualified consent of each state; and if sanctions have been proclaimed in the event of the violation of such a law, these sanctions should have been agreed upon by all in the same way that the laws themselves were, so that no nation can claim to have been forced into participating in a collective action to which it would not have given its consent at the outset.

Finally, there should be a centrally located tribunal to define for each individual case the findings of international law and to rule on their application. Such a tribunal must be one of unquestionable impartiality which compels recognition of its moral authority by virtue of the expert ability and moral caliber of the judges who occupy its benches.

If these three conditions are met – and it will be immediately apparent that all three are in effect contained in one primary condition: the freely given consent of each of the participants – if these conditions are met, then the League of Nations will be able to function, on the one hand with a flexibility which will allow its members to feel secure and at ease within its authority and, on the other hand with the kind of moral force that will preclude the members from even thinking of evading its decisions.

We talk of moral force. But this does not mean that we exclude the use of material force when necessary in extreme cases against nations found guilty of violating the Covenant. We regard it, however, as a last and if these cases do arise, we are convinced that such force must not be employed until it can be established beyond doubt that an act of violence or aggression has been committed, and then only when the guilt of the alleged aggressor is universally acknowledged.

Moreover, the meaning of Article 10 and of Articles 12, 13, 15, and 16 of the Covenant of the League of Nations in no way contradicts the interpretation we have placed upon them. Our American friends have voiced the fear that Article 10 could involve their country in military operations to which it would not have given its consent. To be sure, Article 10 provides a general guarantee preserving the integrity of the territories of each nation9. But none of the articles that follow permits us to conclude that any nation could find itself suddenly involved against its will in a military operation without the explicit consent of the agencies which embody its national sovereignty.

In connection with the difficult problem of limitation of armaments neither the Council nor the Assembly has ever believed it possible to enact relevant statutes without the express support of every nation. Each nation remains free to define and determine the conditions necessary to its internal or external security. In the same way, each nation remains free to give or to withhold its consent to any concerted military action. In the final analysis, the one penalty which can result from the provisions of the Covenant is the loss of the benefits of membership in the League of Nations.

We may be sure that nations will not become attuned in one day to the basic truths which we have tried to define. This will take time and unceasing propaganda, as well as clear evidence of the advantages of association.

We are concerned here with the only kind-of propaganda which is truly successful, which – to borrow an expression which has often been used in an execrable sense, and which we would now like to restore to its better and more edifying connotation – might be called: the propaganda of fact. The fact which we have to impress upon everyone’s mind, a fact powerful enough to triumph over prejudice, to overcome all resistance and disarm any ill will, is the actual fact of international life itself.

Even now there exists in the world an international way of life so powerful and so complex that nobody can avoid its effects. The protection of public health, the provision of transport facilities, the lowering of customs barriers, the creation of an international credit organization – all these are aspects of internationalism from which no nation, however powerful, can claim to be dissociated. In spite of her size, her extensive industrial and commercial influence, America has suffered no less from unemployment than have the nations of Europe. We have only to recall the terrible effects of speculation on the currency exchange to see how impossible it now is to set up anywhere in the world a watertight bulkhead against the flow of international movements.

Exemplifying the necessity of the international way of life by devising instruments for such a life, learning to live together with men of different nations and different races, and highlighting the universal phenomenon of the solidarity of nations and of men – these will constitute the best, the most effective, and the most persuasive lesson it is possible to imagine.

A lesson concerned with such facts would be invaluable. It is not, however, irrelevant to add another. Propaganda must be organized in all civilized countries to impress upon public opinion the true purpose of the League of Nations, the limitations of its power, the true respect which it holds for the laws and the sovereignty of states, that is to say, for the nations themselves, and at the same time the great moral power it wields in the world through the certitude of its principles.

Fortunately, there are already in nearly all nations large associations which disseminate these teachings far and wide, cutting through political bias to the very heart of popular sentiment.

One of the latest creations of the League of Nations bears this significant title: intellectual cooperation10. A committee composed of the most eminent scholars, men of vast learning and brilliant intellect, was set up at one of our recent sessions. Its name is full of promise.

What is intellectual cooperation if not the pooling of all intellectual resources for mutual and equitable exchange, just as material and political interests are pooled? All living organisms must have a driving force, a moving spirit. From all these diverse forces arising from nations and races, is it not possible to give birth to a communal soul, to a common science for a communal life, associating but not absorbing the traditions and hopes of every country in a concerted thrust for justice?

To climb by all roads originating from all points of the world to the pinnacle where the law of man itself holds sway in sovereign rhythm – is this not the ultimate end of mankind’s painful and centuries-long ascent of Calvary?

To be sure, many years of trial must yet elapse, and many retrogressions yet occur before the rumble of human passions common to all men yields to silence; but if the road toward the final goal is clearly marked, if an organization like the League of Nations realizes its potential and achieves its purpose, the potent benefits of peace and of human solidarity will triumph over evil. This at least we may dare to hope for; and, if we will consider how far we have come since the dawn of history, then our hope will gather strength enough to become a true and unshakable faith.

* Mr. Bourgeois, awarded the prize for 1920, was unable to attend the ceremony on December 10 of that year. He later told the Nobel Committee that he would deliver his Nobel lecture sometime between May and September of 1922. Because of illness, he cancelled this intended appearance but in December of 1922 sent to the Committee a manuscript that is called a “communication”. The text of this communication in French which appears in the “Nobel Conférences” [Lectures] section of Les Prix Nobel en 1921-1922 is used for this translation.

1. Hjalmar Branting (1860-1925), co-recipient of the Nobel Peace Prize for 1921, gave his Nobel lecture on June 19, 1922.

2. A provision of the Treaty of Versailles, 1919.

4. An effort by the church to limit fighting to certain days and seasons of the year.

5. Especially the struggles between Huguenots and Catholics in France (1562-1598) and the Thirty Years War (1618-1648).

6. Drawn up by the French revolutionists in 1789 and made the preamble of the French constitution of 1791, the Declaration proclaimed the equality of men, the sovereignty of the people, and the individual’s right to “liberty, property, security”.

7. Hippolyte Adolphe Taine (1829-1893), French critic and historian.

8. The Permanent Court of International Justice, popularly known as the World Court, was set up by the League of Nations in 1921; it was superseded after 1945 by the International Court of Justice, the principal judicial organ of the United Nations.

9. Article 10 of the League of Nations Covenant reads as follows: “The Members of the League undertake to respect and preserve as against external aggression the territorial integrity and existing political independence of all Members of the League. In case of any such aggression or in case of any threat or danger of such aggression the Council shall advise upon the means by which this obligation shall be fulfilled.”

10. The Assembly of the League adopted a resolution presented by Bourgeois concerning the establishment of the Commission on Mutual [Intellectual] Cooperation in September of 1921.

The Nobel Foundation's copyright has expired.Léon Bourgeois – Other resources

Links to other sites

On Léon Bourgeois from L’Assemblée Nationale (in French)

Léon Bourgeois – Conférence Nobel

English

French

Communication de M. Léon Bourgeois au Comité Nobel du Parlement norvégien, Décembre, 1922

Les raisons de vivre de la Société des Nations

Messiuers,

II y a quelques semaines, Mr. Branting venait à Christiania s’acquitter de l’obligation imposée à tous les titulaires du Prix Nobel de la Paix. Je m’excuse de n’avoir pu, l’an dernier, faire de même. L’état de ma santé ne m’a pas permis d’accomplir le voyage de Norvège et j’en ai éprouvé le plus profond regret.

J’ai su, par M. le Président, que vous m’autoriseriez à vous adresser, par une communication écrite, le témoignage de ma reconnaissance et l’exposé des idées dont j’aurais voulu vous apporter l’expression de vive voix. Je vous en adresse, Messieurs, mes bien vifs remerciements.

I

Je suis pleinement d’accord avec M. Branting sur les idées qu’il vous exposait ici, au mois de juin dernier. Avec une grande clairvoyance, il a analysé et ramené à sa mesure vraie «l’immense déception» que la Grande Guerre de 1914-1918 avait fait naître dans les esprits. Certes, ce brusque déchaînement d’un cataclysme, sans égal dans le passé, avait paru donner un démenti formel aux espérances que Nobel avait fait naître, lorsqu’il avait fondé le prix de la Paix; mais, au découragement qui s’était emparé, tout d’abord, de l’opinion, M. Branting opposait les raisons de confiance que l’on pouvait, quand même, tirer de la catastrophe. Il montrait qu’il y avait, dans la cruelle époque que nous avons traversée, sous les ruines accumulées, trop de promesses de renouveau pour que l’on pût considérer la période actuelle comme une période de régression.

La victoire avait été, avant tout, une victoire du droit et de la civilisation. L’écroulement de trois grandes monarchies, principalement fondées sur la puissance militaire, avait donné naissance à de jeunes états, représentants du droit des peuples à disposer d’eux-mêmes, jouissant, en outre, d’institutions démocratiques qui, en faisant dépendre la paix de la volonté directe des citoyens, diminuaient singulièrement, pour l’avenir, les risques de conflit.

Le même mouvement avait amené non seulement la résurrection des nationalités opprimées, mais la réunion, dans une même unité politique, de races jusqu’alors morcelées par la violence.

Enfin, un fait, d’une importance capitale, avait achevé de donner à la victoire des Nations libres sa véritable signification. De l’horreur de quatre années clé guerres avait surgi, comme une suprême protestation, une idée nouvelle qui s’imposait d’elle-même aux consciences: celle de l’association nécessaire des Etats civilisés pour la défense du droit et le maintien de la paix. La Société des Nations, annoncée dès 1899 et 1907 par les Conférences de la Haye, devenait, par le Pacte du 28 juin 1919, une vivante réalité.

Mais, nous apporte-t-elle enfin une organisation durable de la paix? Ou bien allons-nous retrouver, au moment même où nous croyons toucher au but, les obstacles auxquels se sont heurtés, depuis des siècles, les longues théories de ces pèlerins de toutes races, de toutes croyances, de toutes civilisations, s’efforçant, toujours en vain, de s’élever vers l’idéal de la paix?

II

Pour répondre à cette question, qui porte en elle toute l’angoisse de l’humanité, il nous faut remonter non pas seulement à l’histoire des peuples, mais à celle de l’homme lui-même, de l’individu chez qui les passions ne sont pas différentes de celles des collectivités et dont on est certain de retrouver tous les penchants, bons ou mauvais, comme dans un miroir agrandi, lorsque l’on cherche à comprendre les causes des révolutions de l’humanité.

Les passions humaines, comme les forces de la nature, sont éternelles. Il ne s’agit point de les nier; il faut les mesurer et les comprendre. Comme les forces de la nature, elles peuvent être soumises à la volonté réfléchie de l’homme; elles peuvent être mises au service de la raison. Nous retrouverons leur action dans les luttes des états comme dans celles des individus et nous comprendrons, enfin, que les moyens par lesquels celles-ci peuvent être vaincues sont seuls susceptibles de vaincre celles-là.

Affirmer qu’il est possible d’établir la paix entre les hommes des différentes Nations, c’est simplement affirmer que l’homme, quelles que soient sa tendance ethnique, sa race, ses croyances religieuses ou philosophiques, est capable de raison. Deux forces, dans l’individu, concourent au développement de sa conscience et à la formation de sa moralité: sa sensibilité et sa raison.

Sa sensibilité est double. Elle n’est, d’abord, qu’une explosion de l’instinct vital, du besoin de tous les êtres de se développer aux dépens du milieu, au détriment d’autres êtres dont la mort paraît nécessaire à leur propre vie. Mais il existe également une autre forme de l’instinct, qui le rend sensible à la souffrance d’autrui; c’est celle qui crée entre la mère et l’enfant, puis entre le père et le fils, plus tard entre les hommes de la même tribu, du même clan, un lien d’ordre moral; c’est l’instinct de sympathie, qui permet de combattre et de limiter l’instinct brutal et égoïste. Un grand philosophe français, critiquant la doctrine d’après laquelle «on ne pouvait souhaiter autre chose à une race que de parvenir au plein développement de son énergie et de sa faculté de puissance», disait qu’il n’y avait là qu’une vue incomplète’ de ce qu’est l’homme. «C’est prendre l’homme isolément et voir en lui un bel animal, puissant et redoutable. Or, l’homme pris tout entier est l’homme en société et qui se développe: La race supérieure est celle qui est apte à la société et au développement commun». A ce titre, la bonté, le besoin de sociabilité et, à un degré plus élevé, le sentiment de l’honneur, sont des dons spontanés, précieux entre tous et aussi naturels que les autres instincts. Or, ces sentiments existent dans la collectivité d’une Nation comme dans chacun des individus qui la composent. Les faire prédominer sur les poussées de l’égoïsme individuel, c’est la tâche même de la civilisation: il ne faut pas que la puissance de l’individu barre la route dans l’État au reste de la Nation. Il ne faut pas que la puissance d’une Nation barre, dans l’Humanité, la route à l’ensemble de l’Humanité.

Mais l’homme n’a pas en lui que de la sensibilité égoïste ou altruiste; c’est la raison qui est le propre de l’homme. C’est elle qui, chez l’enfant, d’abord incertaine et fragile, puis croissant en puissance, l’amène à concilier dans une harmonie consciente et durable, et non plus par impulsions violentes et contradictoires, les deux tendances de sa sensibilité. C’est elle qui, depuis le commencement de l’Histoire, amène peu à peu les hommes, au cours des civilisations successives, à reconnaître qu’il y a un état préférable à celui de la lutte brutale pour la vie, un état moins périlleux, seul conforme aux révélations de sa conscience et qui est, sous des formes toujours plus complexes et plus solides, le véritable état de société.

L’ascension de l’animal à l’homme s’est prolongée par l’ascension de l’Humanité de la barbarie à l’ordre, de la violence à la paix; et c’est de même la raison qui amène enfin l’homme à formuler, sous le nom de droit, des limites que chaque homme doit s’abstenir de franchir s’il veut demeurer digne de rester dans l’état de société.

* * *

Ce sont les religions qui, tout d’abord, ont formulé le droit. Il en est résulté que ce droit n’était reconnu qu’au profit de ceux qui pratiquaient le même culte et semblaient des égaux protégés par les mêmes dieux. Pour les sectateurs de tous les autres cultes, il n’y avait ni droit ni pitié. C’est la période des divinités implacables, de Baal et de Moloch; c’est encore celle de Jéhovah ordonnant à son peuple l’extermination des vaincus.

La philosophie grecque élève pour la première fois, au-dessus du Monde, le flambeau de la raison. Elle aboutit au stoïcisme où tous les hommes sont égaux et «sont les membres d’un seul corps», où la volonté humaine, réglée par le droit, est proposée à l’homme comme le moteur suprême de son activité.

Cette doctrine de la volonté humaine se traduit dans le droit romain de l’Epoque impériale par cette admirable théorie des obligations qui fait dépendre, dans le droit privé, la validité des contrats du libre consentement des contractants.

Mais que de chemin à parcourir encore entre ces affirmations du droit privé et la reconnaissance du même droit comme règle suprême de la politique des Nations!

Le christianisme vient, à son tour, donner au sentiment de pitié qui s’était spontanément développé chez les hommes une forme et une puissance inconnues jusqu’à lui. Ce que prêche la doctrine du Christ, c’est l’amour des hommes, tous considérés comme frères; c’est la condamnation de la violence: »celui qui se servira de l’épée périra par l’épée»; c’est la communion chrétienne supérieure à toutes les nationalités et ouvrant aux Gentils, c’est à dire aux Nations de toute la terre, l’espérance d’une vie meilleure où la justice, enfin, régnera.

Le Moyen-Age, tout entier, est l’historié du développement de cette doctrine et l’effort de la Papauté marque, pendant plusieurs siècles, la volonté persistante de faire descendre sur la terre, sinon la justice elle-même, qui semble encore au-delà des forces humaines, et qu’on remet au «jugement de Dieu», du moins une paix relative et temporaire, «la trêve de Dieu, qui donne aux malheureux humains une halte dans la souffrance, un court instant de sécurité.

Mais une nouvelle période de combats allait, à son tour, bouleverser l’Europe, avec les Guerres de religion, les plus cruelles, peut-être, puisqu’-elles obligent la conscience elle-même à répudier la pitié et semblent élever l’une contre l’autre les deux forces qui s’étaient jusqu’alors partagé le monde: le sentiment et la raison. Et c’est seulement au 18ème siècle qu’il appartiendra, en lin de compte, de les réconcilier.

La Déclaration des Droits de l’Homme affirmaient, enfin, pour l’Humanité toute entière, les principes de justice sans lesquels il serait toujours impossible de fonder une véritable paix.

Que de souffrances, que de sang il a fallu, pourtant, pendant encore plus d’un siècle, pour qu’on puisse enfin espérer l’application des principes de morale vraiment humaine proclamés par la Révolution française! Il a fallu, comme dit Taine, «multiplier les idées, établir la délibération préalable dans l’intelligence consciente, grouper les pensées humaines, par un travail conscient encore, autour de préceptes acceptés: bref, refaire, sous la dictée de l’expérience, l’intérieur de la tète humaine».

La plus grande révolution de l’Histoire n’est-elle pas celle qui a permis à la raison de considérer vraiment l’Humanité toute entière comme sujet du droit et de reconnaître le titre d’homme à tous les humains.

Tous les hommes égaux en droits et en devoirs, solidaires du sort de l’Humanité, quel rêve:

L’idée du droit maîtresse du monde va-t-elle enfin donner raison à la raison?

III

Sommes-nous arrivés à un développement de la moralité et de la civilisation universelles qui nous permette de considérer comme viable une Société des Nations? Si elle est possible, quels sont les caractères et les limites mêmes qu’elle doit présenter pour correspondre à l’état actuel du Monde ?

Certes, un progrès immense s’est déjà réalisé dans l’organisation politique, sociale, morale du plus grand nombre des états.

L’extension de l’instruction publique dans presque toutes les parties du globe agit puissamment sur les esprits;

la prédominance des institutions démocratiques s’affirme dans tous les États civilisés;

la régression des préjugés de caste, qui s’opposent au passage d’une classe à l’autre et en retardent la disparition, l’échec, même en Russie, des systèmes d’organisation communistes qui prétendent imposer à la liberté et à l’initiative de l’individu des barrières infranchissables;

enfin, l’ensemble des institutions sociales d’assistance, de prévoyance et de solidarité qui mettent le devoir en regard du droit de chacun et, d’une manière générale, la conception d’une justice de plus en plus humaine où la responsabilité des fautes de l’individu ne sera plus séparée de la responsabilité de la société elle-même;-

tous ces faits préparent, dans chacune des Nations, la révolution intellectuelle dont nous avons parlé et amène les peuples à concevoir et à comprendre la supériorité, bientôt même la nécessité d’institutions internationales où les mêmes principes seront reconnus et appliqués.

Il reste, il est vrai, en dehors du mouvement qui emporte les civilisations vers cet état supérieur de conscience, des territoires immenses où les populations, tenues depuis des siècles dans l’esclavage ou la servitude, n’ont point encore reçu les premiers rayons de l’idée rénovatrice et pour lesquelles s’impose une période, sans doute assez longue encore, de culture intellectuelle et morale.

Mais c’est déjà un fait nouveau et considérable que les Nations civilisées, comprenant «leur mission sacrée de civilisation», aient, aux termes de l’article 22 du Pacte, accepté de se charger envers ces peuples arriéres d’un mandat d’éducation, «afin de les rendre capables de se diriger eux-mêmes dans les conditions particulièrement difficiles du monde moderne».

* * *

Ce n’est pas seulement au point de vue de l’ensemble des institutions et des mours, mais c’est aussi au point de vue purement politique, au point de vue de la carte même de l’Europe et du monde qu’un progrés s’est réalisé.

Lorsqu’en 1899, la Conférence de La Haye, réunie sur la convocation du Tsar, posa, devant l’univers civilisé, le problème du désarmement et de la paix, et prononça pour la première fois le nom de »Societé des Nations, il était a priori certain que le problème ne pourrait pas être résolu à cette date. La géographie politique de l’Europe était, sur trop de points, fondée sur la violation du droit des peuples. Comment aurait-on pu prendre son état comme la base de l’organisation d’une paix conforme à ce droit?

Aujourd’hui, la guerre a permis de faire disparaître le plus grand nombre des injustices d’alors, En Europe, l’Alsace-Lorraine a été rendue à la France; la Pologne a été reconstituée dans son unité et son indépendance: Tchéco-Slovaques, Danois, Belges, Slaves et Latins ont retrouvé le droit de se gourverner eux-mêmes ou sont retournés à leur mère-patrie.

En Asie même, à l’heure où nous parlons, un grand effort est fait pour trouver, entre les droits historiques des différentes races, un équilibre durable dans la légalité et la paix.

Est-ce à dire que, soit en Europe, soit dans les autres parties du inonde, toute cause de trouble ait disparu : Nous sommes loin d’avoir une confiance aveugle dans l’avenir et nous avons sous les yeux des preuves trop évidentes, des manifestations de troubles trop certains pour que nous songions à les nier.

D’une part, des puissances qui ont été vaincues dans la grande guerre n’ont pas suffisamment consenti au désarmement moral qui est la condition première de toute pacification. Des minorités turbulentes, de caractère incertain, trop faibles pour constituer des états véritables, révoltées contre la grande majorité des citoyens d’une même région, cherchent leur appui en dehors des frontières naturelles où s’alimente la vie commune et risquent de créer des foyers d’agitation et de violence où devrait régner une tolérance réciproque et se fonder une mutuelle solidarité.

D’autre part, des mouvements artificiels s’élèvent qui cherchent à franchir les bornes de chacun des Etats et tendent à grouper, dans des mélanges inorganiques, les peuples les plus divers; mouvement pangermaniste, mouvement panislamique, mouvement pannoir fondent leur raison d’être tantôt sur l’unité de langue, tantôt sur l’unité de croyance religieuse, tantôt sur limité de couleur, et ne sont que des éléments de menace pour la paix générale. Il y a dans ces agglomérations sans mesure un danger grave, quelque chose d’essentiel leur fait défaut: la véritable unité de vie, la conscience supérieure d’une destinée commune.

Tout cela, du reste, peut n’être que passager; il semble qu’il s’agisse surtout des convulsions dernières du cataclysme qui a bouleversé le monde.

Mais il y a quelque chose de plus profond dont il faudra toujours tenir compte dans une organisation internationale, quelle qu’elle puisse être. M. Branting, dans la communication qu’il vous faisait il y a quelques mois, montrait qu’entre l’Internationale des classes telle que certains congrès socialistes l’ont envisagée et la véritable Internationale des Nations, il y avait un abîme, que, par celle-ci seulement, la paix pouvait être véritablement organisée entre tous les hommes, au lieu d’être seulement espérée, contre toute espérance raisonnable, d’une lutte préalable entre les hommes d’un même pays.

Loin d’opposer l’idée de patrie à l’idée d’humanité, il faut, en effet, affirmer avec force que les hommes qui servent le mieux la cause de la paix sont, en vérité, les plus patriotes. La patrie est, elle ne peut être que l’élément organique par excellence de toute Société des Nations. De même que la constitution de la famille est à la base de la constitution de la Nation, c’est entre les patries seules que peuvent s’établir les liens qui constitueront la vie d’une Société internationale.

La guerre de 1914-1918, qui a été une guerre de libération des nationalités, n’a pu que surexciter ce sentiment national. Elle a donné aux tendances intellectuelles et morales, qui constituent le sentiment de la patrie, une force plus grande; elle a rendu ce sentiment, légitime entre tous, plus jaloux. Il en résulte que l’organisation internationale projetée doit reposer en dernière analyse non seulement sur la souveraineté intangible de chaque état, mais sur l’égalité de droits entre tous, qu’ils soient puissants ou faibles, grands ou petits. C’est entre des Etats régulièrement constitués, et seulement entre eux, qu’il peut s’agir d’établir le règne du droit.

Pour les mêmes raisons, on ne pouvait songer à une organisation s’imposant du dehors aux Etats. L’idée d’un sur-Etat, d’une volonté obligeant les organes souverains de chacune des Nations, eut amené la révolte du patriotisme. Ce qui était à la fois nécessaire et suffisant, c’est que chacune des Nations comprit que le consentement mutuel à certains principes de droit, à certains accords reconnus comme également profitables aux divers contractants ne constituait nullement un abandon de souveraineté, pas plus que, dans le domaine des intérêts privés, le contrat n’est une renonciation à la liberté, mais l’usage réfléchi et reconnu avantageux aux deux parties de cette liberté elle-même.

* * *

Mais quelle est donc la condition fondamentale de ce consentement mutuel, la condition exigible pour qu’il soit donné sans arrière-pensée, pour que le sentiment existe, de part et d’autre, que rien d’essentiel, qu’aucun intérêt vital ne sera sacrifié par l’une des Nations contractantes?

Il faut qu’il y ait une règle supérieure, une norme souveraine à laquelle chacun des accords puisse être comparé, comme, dans le domaine des sciences, l’homme, se défiant de ses sens incertains, se reporte, pour la comparaison et la mesure des phénomènes, au témoignage d’instruments invariables que le coefficient d’erreurs personnelles ne pourra, en aucun cas, influencer.

Dans l’ordre moral, c’est le droit, proclame en dehors de toute considération individuelle ou nationale, antérieur et supérieur aux variations de l’opinion, qui sera le témoin, l’impartial enregistreur des prétentions en présence et qui, par l’indépendance absolue, par le caractère indiscutable de son témoignage, apaisera les passions, désarmera les mauvaises volontés, découragera les ambitions illusoires et créera l’atmosphère de confiance et de calme où, seulement, pourra naître et se développer la plante fragile de la paix.

Ce droit, arbitre souverain et sans appel, existe-t-il en fait?

L’histoire des derniers siècles nous permet clé répondre affirmativement.

Il existe bien, désormais, un droit international dont la doctrine est certaine et dont la jurisprudence n’est contestée par aucun pays civilisé. Le 19ème siècle, qui ouvrit les Conférences de La Haye et provoqua, sur les sujets les plus divers, de nombreuses Conférences internationales, a vu s’en multiplier les applications. Si les violations de ce droit, en 1914 et pendant les années de guerre, ont été malheureusement trop évidentes, la Victoire en a fait justice; si elles devaient se reproduire un jour, il faudrait vraiment désespérer de l’avenir de l’Humanité.

D’abord purement théorique et doctrinal, le droit international s’enrichit peu à peu par de nombreuses conventions où se trouvent, en fait, réglées juridiquement, les obligations essentielles, celles qui peuvent être définies avec précision, qui peuvent être codifiées, rendues légalement obligatoires et soumises à des sanctions. Le cadre de ces conventions ne cesse de s’élargir; il se pénètre peu à peu des idées morales qui constituent ce que j’ai appelé, dans une étude récente, la morale internationale; il s’étend à tout ce qui touche à la vie, à la santé, au bien-être matériel et moral de tous les humains.

Le droit international existe donc.

Mais peut-on espérer qu’il trouvera dans une organisation juridique, également souveraine, un interprète fidèle et, comme lui, placé au-dessus de toutes les passions?

L’histoire toute récente des délibérations de la Société des Nations: la création de la Cour de justice internationale, nous permet de donner encore une réponse affirmative à cette seconde question.

IV

Résumons les trois conditions auxquelles paraît devoir être subordonnée une organisation internationale correspondant à l’état actuel de la civilisation.

Il faut, d’abord, qu’il y ait entre les états associés une suffisante communauté de sentiments et de pensées, un développement sinon tout à fait égal, du moins suffisamment analogue pour que soient comprises les vérités de l’ordre international et soient admises les règles qui procèdent à leur développement,

Il faut, ensuite, que chacune des règles ainsi consenties l’aient été véritablement par la volonté libre de chacune des Nations, que si des sanctions ont été prononcées, au cas de violation de quelqu’une de ces règles, ces sanctions aient été consenties comme les règles elles-mêmes et qu’aucun des Etats ne puisse se plaindre qu’il ait été, malgré lui, entraîné dans une action collective qu’il n’aurait pas préalablement acceptée.

Il faut, enfin, qu’il y ait, au milieu du monde, pour définir, dans chaque cas particulier, le droit international et pour en régler l’application, un tribunal dont l’impartialité soit au-dessus de toute contestation, dont l’autorité morale s’impose à raison de la valeur scientifique et de la haute moralité–dés magistrats qui le composent.

Si ces trois conditions sont réunies, et toutes les trois, on le voit, répondent, en somme, à la même condition première: le consentement libre de chacun des contractants, une Société des Nations pourra vivre avec une souplesse suffisante pour que chacun se trouve à l’aise dans ses cadres et une force morale également suffisante pour que nul ne puisse songer à se dérober à ses décisions.

* * *

Nous disons une force morale. Nous n’entendons pas exclure ainsi, dans les cas extrêmes, la nécessité de l’emploi d’une force matérielle à l’égard des Etats qui se seraient rendus coupables d’une violation du Pacte, mais nous entendons réserver cette force matérielle comme une ultima ratio, et nous sommes persuadés que si elle est, dans certains cas, nécessaire, elle ne doit être employée que si l’on se trouve en présence d’un acte de violence ou d’agression indiscutable et si c’est, pour ainsi dire, avec le consentement universel que l’Etat violateur sa sera trouvé condamné.

Au surplus, le sens de l’article 10 et des articles 12, 13, 15 et 16 du Pacte de la Société des Nations n’est nullement contraire à l’interprétation que nous en avons donnée. Nos amis d’Amérique ont exprimé la crainte que l’article 10 put entraîner leur pays dans des opérations militaires auxquelles il n’aurait pas consenti. Certes, l’article 10 édicté une garantie générale de l’intégrité du territoire de chacun des États associés, mais aucun des articles suivants ne permet de conclure que, sans la libre acceptation des organes de la souveraineté nationale de chacun des États, l’un quelconque d’entre eux pourrait se trouver, malgré lui, sans son consentement explicite, entraîné par surprise à quelque action militaire.

Dans le difficile problème de la limitation des armements, jamais, ni le Conseil, ni l’Assemblée n’ont cru qu’il serait possible de statuer sans l’adhésion expresse de chacun des États. Chacun reste libre de définir et de fixer les conditions de sa sécurité nécessaire, intérieure ou extérieure. De même, chacun reste libre de donner ou de refuser son consentement à toute action militaire concertée. La seule sanction qui puisse, en dernière analyse, résulter des dispositions du l’acte, est la renonciation au bénéfice de la Société des Nations.

* * *

Ce n’est certainement pas en un jour que l’esprit des peuples sera suffisamment pénétré des vérités essentielles que nous nous sommes efforcés de définir. Il y faudra du temps, une propagande incessante et la constatation des résultats heureux de l’association.

Il s’agit ici de la seule propagande qui soit véritablement efficace, de celle qui–suivant une expression qui a été bien souvent employée dans un sens détestable, que nous voulons retourner, nous, dans le sens le meilleur et le plus élevé -, peutètre appelée: la propagande par le fait. Le fait dont il s’agit de pénétrer les esprits, le fait assez puissant pour triompher des préjugés, pour vaincre les résistances, pour désarmer les mauvaises volontés : c’est le fait de la vie internationale elle-même.

Il y a, dès maintenant, dans le monde, une vie internationale tellement complexe, tellement puissante, que nul ne peut, désormais, tenter de se soustraire à son action. Défense de la santé publique, facilité des transports, abaissement des barrières douanières, organisation internationale du crédit, autant de terrains sur lesquels il est impossible à aucun État, quelque puissant quil soit, de prétendre rester étranger. Quelque grande que soit l’Amérique, quelque étendue que soit sa puissance industrielle et commerciale, elle n’a pas souffert du chômage moins que les Etats d’Europe. Il suffit de signaler les effroyables effets de la spéculation sur le change pour voir à quel point il est dorénavant impossible d’établir sur aucun point du Monde une cloison étanche pour arrêter le flux des mouvements internationaux.

Donner, par la constitution des organes de la vie internationale, l’exemple de la nécessité de cette vie même; apprendre à vivre en commun aux hommes des différentes Nations et des différentes races; faire apparaître en lumière, au-dessus de tous, le phénomène universel de la solidarité des Nations et des hommes, ce sera là la leçon la meilleure, la plus efficace et la plus persuasive qu’il est possible d’imaginer.

Cette leçon des faits sera certainement la plus efficace. Il n’est cependant pas inutile d’y ajouter un autre enseignement. Il faut qu’une propagande s’organise dans tous les pays civilisés pour faire comprendre à l’opinion universelle le but véritable de la Société des Nations, les limites de ses pouvoirs, son respect sincère des droits de la souveraineté des Etats, c’est-à-dire des Patries elles-mêmes, en même temps que la grande puissance morale que la certitude de ses principes lui assure dans le monde.

Il s’est heureusement créé dans presque tous les états de grandes associations qui répandent largement ces enseignements et les feront pénétrer, au-delà des partis politiques, jusqu’aux couches profondes du sentiment populaire.

Une des dernières créations de la Société des Nations porte, d’ailleurs, ce nom significatif: la coopération intellectuelle. Un Comité composé des savants les plus éminents, des intelligences les plus vastes et les plus hautes, a été constitué à une de nos dernières sessions. Son nom est plein de promesses.

Qu’est-ce que la coopération intellectuelle, sinon la mise en commun de toutes les forces de l’intelligence, comme sont mis en commun les intérêts matériels et politiques, associés dans un mutuel et équitable échange. A des organismes vivants, il faut un moteur, il faut une âme. De toutes les âmes diverses qui sont celles des Nations et des races, est-il impossible de faire naître une âme commune, une science commune de la vie commune, associant sans les confondre, dans un même élan vers la justice, les tendances, les aspirations de chaque Patrie?

Monter par tous les chemins, qui partent de tous les points du monde, vers un unique sommet, d’où se découvre la loi même de l’homme en suit rythme souverain, n’est-ce pas là le terme dernier du douloureux calvaire qu’a dû, pendant tant de siècles, gravir l’Humanité?

Certes, il faudra encore bien des années d’épreuves, bien des retours en arrière avant que les passions humaines qui grondent chez tous les hommes soient prêtes à désarmer; mais si la route est clairement tracée vers le but, si une organisation semblable à celle que représente actuellement la Société des Nations se complète et s’achève, la puissance bienfaisante de la paix et de la solidarité humaine l’emportera sur le mal. C’est en tout cas ce que nous avons le droit d’espérer; et, si nous considérons la route poursuivie depuis le commencement de l’Histoire jusqu’aux heures présentes, notre espoir se fortifiera jusqu’à devenir une foi véritable, un inébranlable foi.

The Nobel Foundation's copyright has expired.Léon Bourgeois – Nominations

The Nobel Peace Prize 1920

Remarks at the Award Ceremony by Anders Johnsen Buen*, President of the Norwegian Parliament, on December 10, 1920

The letter from the Nobel Committee of the Norwegian Parliament reads as follows: “The Nobel Committee of the Norwegian Parliament has the honor of announcing herewith its decision to award the Nobel Peace Prize for 1919 to the President of the United States of America Mr. Woodrow Wilson and that for 1920 to Mr. Léon Bourgeois, president of the French Senate and president of the Council of the League of nations.”

Today, Gentlemen, as the Norwegian Parliament meets to present the Nobel Peace Prize for the first time since the World War1, it is with the conviction that the great ideal of peace, so deeply rooted in the hopes for survival of the nations, will gain fresh ground in the minds of men as a result of the recent tragic events.

[President Buen then speaks of Woodrow Wilson – included in the section on Wilson.]

And the other Peace Prize, awarded to Léon Bourgeois, is accompanied by a salute from Norway to the will for peace of the French people, whom he has represented with great distinction for many years through good days and bad.

* Mr. Buen addressed these remarks to the Parliament at an official session on December 10, 1920, doing so after the Nobel Committee had announced its decision and after the diplomatic representatives of the two absent laureates had been officially admitted to the meeting. He then gave the Nobel diplomas and medals to the two ministers. Mr. Pralon, the French minister, accepted on behalf of Mr. Bourgeois, expressing the laureate’s regret at not being there to speak for himself and his gratitude, along with that of France, for the recognition given. The translation of Mr. Buen’s comments is based on the Norwegian text in Forhandlinger i Stortinget (nr. 502) for December 10, 1920 [Proceedings of the Norwegian Parliament].

The Nobel Peace Prize 1920

Léon Bourgeois – Biographical

Léon Victor Auguste Bourgeois (May 21, 1851-September 29, 1925), the «spiritual father» of the League of Nations, was a man of prodigious capabilities and diversified interests. A statesman, jurist, artist, and scholar, Léon Bourgeois, in the course of a long career, held almost every major office available in the French government of the Third Republic.

The son of a clock-maker of Jurassian and Burgundian descent, Bourgeois lived most of his life in Paris in an eighteenth-century townhouse on the rue Palatine. He was an insatiable student, reflective, diligent, enthusiastic, and possessed of a happy propensity for becoming involved in whatever he did. Concerned throughout his life with the improvement of man’s condition through education, justice under the law, medical care, and the abolition of war, he was that political anomaly, a politician without personal ambition, who twice refused to run for the presidency of the Republic despite assurances that he could easily capture it.

As a schoolboy at the Massin Institution in Paris, Bourgeois displayed his intelligence, leadership, and oratorical flair early. He continued his education at the Lycée Charlemagne, and, after fighting in an artillery regiment during the Franco-Prussian War, enrolled in the Law School of the University of Paris. His education was remarkably broad. He studied Hinduism and Sanskrit, worked in the fine arts, becoming knowledgeable in music and adept in sculpture – indeed, at the height of his political career he exercised his talent as a craftsman, so it is reported, by drawing caricatures of his colleagues in cabinet meetings.

In 1876, after having practiced law for several years, he assumed his first public office as deputy head of the Claims Department in the Ministry of Public Works. In rapid succession he became secretary-general of the Prefecture of the Marne (1877), under-prefect of Reims (1880), prefect of the Tarn (1882), secretary-general of the Seine (1883), prefect of the Haute-Garonne (1885), director of personnel in the Ministry of the Interior (1886), director of departmental and communal affairs (1887). In November of 1887, at the age of thirty-six, he was appointed chief commissioner of the Paris police.

When in February, 1888, Bourgeois defeated the formidable General Boulanger to become deputy from the Marne, his political future was assured. He joined the Left in the Chamber, attending the congresses of the Radical-Socialist Party and rapidly becoming their most renowned orator. He was named undersecretary of state in Floquet’s cabinet (1888), elected deputy from Reims (1889), chosen minister of the Interior in the Tirard cabinet (1890).

As minister of public instruction in Freycinet’s cabinet from 1890 to 1892 and again in 1898 under Brisson, Bourgeois instituted major reforms in the educational structure, reconstituting the universities by regrouping the faculties, reforming both the secondary and primary systems, and extending the availability of postgraduate instruction. When he gave up the education portfolio in 1892, he accepted that of the Ministry of Justice for two years.

On November 1, 1895, Bourgeois formed his own government. His political program included the enactment of a general income tax, the establishment of a retirement plan for workers, and implementation of plans for the separation of church and state, but his government succumbed, not quite six months old, to a constitutional fight over finances.

Chairman of the French delegation to the first Hague Peace Conference in 1899, Bourgeois presided over the Third Commission, which dealt with international arbitration, and, together with the chairmen of the British and American delegations, was responsible for the success of the proposal adopted by the Conference to establish a Permanent Court of Arbitration. In early 1903, after the Court had become a reality, he was designated a member.

Bourgeois became president of the Chamber of Deputies in 1902; briefly withdrew from public life in 1904 because of poor health; traveled for a time in Spain, Italy, and the Near East; resisted the urging of his friends to run for the presidency; sought and won election as senator from the Marne in 1905, an office to which he was continuously elected until his death; became minister of foreign affairs under Sarrien in 1906.

In 1907, Bourgeois represented his country at the second Hague Peace Conference where he served as chairman of the First Commission on questions relating to arbitration, boards of inquiry, and pacific settlement of disputes. His speeches at The Hague and at other peace conferences were published in 1910 under the title Pour la Société des Nations.

Soon after the turn of the century, Bourgeois twice declined the invitation of the president of the Republic to form governments, but he continued his services to the nation in other posts. He was minister of public works under Poincaré (1912), minister of foreign affairs under Ribot (1914), minister of state during the war, minister of public works (1917).

In January of 1918, heading an official commission of inquiry on the question of a League of Nations, he presented a draft for such an organization. President of a newly formed French Association for the League of Nations, he attended the 1919 international congress, convened in Paris, of various organizations interested in establishing a League, and in the same year served as the French representative on the League of Nations Commission chaired by Woodrow Wilson. He brought out another collection of his speeches at this time, Le Pacte de 1919 et la Société des Nations.

The culmination of Bourgeois’ career came in 1920 when he assumed the presidency of the French Senate, was unanimously elected the first president of the Council of the League of Nations, and was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize.

Because of deteriorating health and approaching blindness, he was unable to travel to Oslo to accept the prize in person, and in 1923 he retired from the Senate. He died at Château d’Oger, near Epérnay, of uremic poisoning at the age of seventy-four. The French people honored him with a public funeral.

| Selected Bibliography |

| Boulen, Alfred-Georges, «Exposé de la doctrine de M. Bourgeois: La Pente socialiste», in Les Idées solidaristes de Proudhom, pp. 23 -74. Paris, Marchal & Godde, 1912. |

| Bourgeois, Léon, L’Oeuvre de la Société des Nations, 1920-1923. Paris, Payot, 1923. |

| Bourgeois, Léon, Le Pacte de 1919 et la Société des Nations. Paris, Charpentier, 1919. |

| Bourgeois, Léon, Pour la Société des Nations. Paris, Charpentier, 1910. |

| Bourgeois, Léon, Solidarité. Paris, Colin, 1896. |

| Brisson, Adolphe, «M. Léon Bourgeois», in Les Prophètes, pp. 268-286. Paris, Tallandier & Flammarion, [1903]. |

| Buisson, Ferdinand, La Politique radicale: Étude sur les doctrines du parti radical et radical socialiste. Paris, Giard & Brière, 1908. |

| Dictionnaire de biographic française. |

| Hamburger, Maurice, Léon Bourgeois, 1885-1925. Paris, Librairie des sciences politiques et sociales, 1932. |

| Obituaries: Journal des Économistes, 82 (octobre, 1925) 247-249; (London) Times (September 30, 1925); New York Times (September 30, 1925). |

| Schou, August, Histoire de l’internationalisme III: Du Congrès de Vienne jusqu’à la première guerre mondiale (1914), pp. 449-451. Publications de l’lnstitut Nobel Norvégien, Tome VIII. Oslo, Aschehoug, 1963. |

| Scott, James Brown, «Léon Bourgeois, 1851-1925», in American Journal of International Law, 19 (October, 1925) 774-776. |

This autobiography/biography was written at the time of the award and first published in the book series Les Prix Nobel. It was later edited and republished in Nobel Lectures. To cite this document, always state the source as shown above.

The Nobel Foundation's copyright has expired.