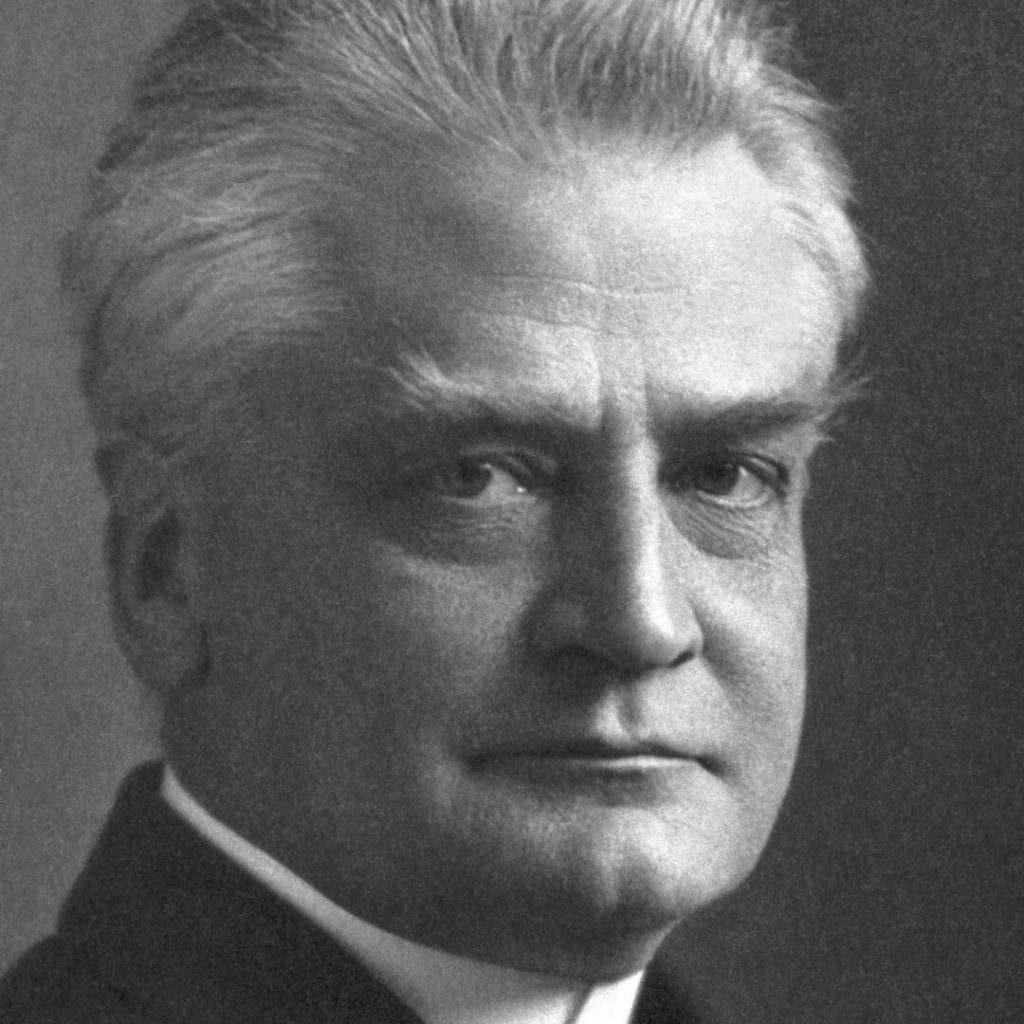

In the first third of the twentieth century, Christian Lous Lange became one of the world’s foremost exponents of the theory and practice of internationalism …

Christian Lange – Speed read

Christian Lous Lange was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize, jointly with Karl Hjalmar Branting, for his lifelong contributions to the cause of peace and organised internationalism.

Full name: Christian Lous Lange

Born: 17 September 1869, Stavanger, Norway

Died: 11 December 1938, Oslo, Norway

Date awarded: 10 December 1921

Advocate of internationalism

In 1921 Christian Lange of Norway was awarded the peace prize for his efforts to promote international cooperation. Lange served as the first secretary of the Norwegian Nobel Committee and helped to build up the Nobel Institute in Oslo. He also participated in the political activities that culminated in 1905 in the dissolution of the union between Norway and Sweden. In 1909 Lange became secretary-general of the Inter-Parliamentary Union, which hosted conferences for parliamentarians from various countries, managing to keep the organisation intact throughout WWI. In 1920 Lange became a permanent Norwegian delegate to the League of Nations, and in the 1930s he cautioned against the aggressive policies of Japan, Italy and Germany. Lange was appointed a member of the Nobel Committee in 1934.

”Thus, a world federation, in which individual nations linked in groups can participate as members, is the political ideal of internationalism.”

Christian L. Lange, Nobel Prize lecture, 13 December 1921.

| Inter-Parliamentary Union Founded in 1889 to bring together representatives from various national assemblies for annual debates. Headquartered in Geneva. Works for the peaceful resolution of conflict between nations. Addresses topics such as disarmament, environmental protection, gender equality and current world conflicts. |

Lange and the dissolution of the union in 1905

In 1905 Norway withdrew from a union with Sweden that had lasted since 1814. Many Swedes viewed the move as an act of rebellion. Soon the countries were on the brink of war, but negotiations resulted in a peaceful solution. Chairman of the Norwegian Nobel Committee Jørgen Løvland was Norway’s minister of foreign affairs in 1905. During the conflict with Sweden, he employed the linguistically gifted secretary of the Nobel Institute, Christian Lange, to present Norwegian views abroad.

”… as Norwegians, we have some cause for pride in the fact that one of our fellow countrymen has done so well in the world …”

Member of the Nobel Committee Halvdan Koht, From the Norwegian newspaper 17. Mai, 12 December 1921.

Lange’s international efforts

Lange served as secretary general of the Inter-Parliamentary Union (IPU). At the outbreak of WWI the IPU headquarters were located in Belgium. When Germany invaded Belgium in 1914, Lange moved back to Norway and maintained contact with the parliamentarians from the warring countries for the duration of the conflict. In 1919 Lange moved the IPU headquarters to Geneva where the League of Nations was also located. Lange became one of Norway’s delegates to the League, where he spoke out against the dangers of fascism, Nazism and chauvinistic nationalism.

| Fascism Name of the bundle of rods symbolising the authority of the ancient Roman magistrates. Name of political party founded by Benito Mussolini in Italy in 1919. Fascists cultivated violence and despised democracy, believing that nations should have a ruling elite and a strong leader. |

| Nazi Party A byname for the Nationalsozialistische Deutsche-Arbeiterpartei (National Socialist German Workers’ Party). Followers of Adolf Hitler’s policies and philosophy. A nation’s citizens should obey a strong leader and the Aryan race was superior to all others. |

| Chauvinism Extreme nationalism that claims people of one particular nationality are superior to all others. In its most extreme form, chauvinism results in racism. |

Lange as Nobel Committee member

Christian Lange served as the first secretary of the Norwegian Nobel Committee. After stepping down from this post, he served as adviser to the committee for many years, compiling reports for the Nobel Committee on the nominated candidates. Appointed as a member of the Nobel Committee in 1934, Lange participated in the dramatic events surrounding the 1935 Nobel Peace Prize award to German pacifist Carl von Ossietzky, who was imprisoned in one of Hitler’s concentration camps. The award made Hitler so furious that he banned all Germans from accepting any Nobel Prizes in the future.

”The heroes of peace are not named to the ranks by their success in building an everlasting peace, but by their tireless exertions as ‘faithful guardians of the highest interests of mankind’… Such a hero was Christian Lange.”

Professor Irwin Abrams in Karl Holl/Anne C. Kjelling: The Nobel Peace Prize and the Laureates, page 176, Peter Lang 1994.

Learn more

Disclaimer: Every effort has been made by the publisher to credit organisations and individuals with regard to the supply of photographs. Please notify the publishers regarding corrections.

Hjalmar Branting – Speed read

Karl Hjalmar Branting was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize, jointly with Christian Lous Lange, for his lifelong contributions to the cause of peace and organised internationalism.

Full name: Karl Hjalmar Branting

Born: 23 November 1860, Stockholm, Sweden

Died: 24 February 1925, Stockholm, Sweden

Date awarded: 10 December 1921

Social democrat and internationalist

Hjalmar Branting is considered to be the father of Swedish socialism. He was the driving force behind the formation of the Social Democratic Labour Party in 1889 and a leader in the struggle for democratisation of Sweden. When Norway withdrew from the union with Sweden in 1905, Branting defended Norway’s right to full autonomy and opposed Swedes who sought to keep Norway in the union by force. Branting believed that a just society must be obtained by peaceful means rather than by revolution. He strongly advocated international cooperation and supported the creation of the League of Nations after WWI. In 1920 he was appointed as a delegate to the League in Geneva, where he came to play a leading role. The same year he became the first social democratic prime minister of Sweden.

| Social democrat Term for those who believed that a classless society as described by Karl Marx could be achieved by peaceful means, rather than by revolution. Today the term refers to those who support a state-regulated market economy and public solutions to social problems. |

“Branting is decidedly the most exceptional personality to be fostered not just by the Swedish but the Nordic workers’ movement to date, laying the foundation more than any individual for the prominent position of Swedish social democracy through his wise leadership.”

Aschehoug/Gyldendal Store Leksikon, Volume 2 page 562, Kunnskapsforlaget 1986.

Branting and the dissolution of the union in 1905

“The best action we Swedes can take is to support our friends in the Norwegian party, as they choose to dismantle this union that is hindering their development,” said Branting about the Norwegian-Swedish union. The two nations shared a king and foreign policy, but democracy was developing at a faster pace in Norway than in Sweden. For this reason, Branting wanted to maintain the union; Norway could provide the leverage needed to promote universal suffrage and parliamentarianism in Sweden. But when Norwegians moved to withdraw from the union, Branting staunchly supported their right to full sovereignty.

“… a practical statesman and an international pioneer for peace. He has demonstrated this in practice by his efforts for a peaceful settlement in the matter of the union between Sweden and Norway.”

Halvdan Koht, member of the Nobel Committee, 10 December 1921.

Branting’s fight for democracy

Hjalmar Branting led the Swedish Social Democratic Labour Party from its inception in 1889. He fought for freedom of the press, universal suffrage, an eight-hour workday, adequate public schooling and the separation of church and state. He sought to dismantle the regular army, which could be misused to oppress the labour movement, proposing instead to establish a Swedish home guard designed according to the Swiss model. Branting opposed Lenin’s revolutionary ideas, believing that democratisation should be achieved peacefully by empowering the workers through voting rights and free elections.

Branting in the League of nations

Hjalmar Branting represented Sweden in the newly-formed League of Nations after WWI. He deeply regretted that the USA did not become a member and disapproved of the decision to exclude Germany and Russia. The first international issue to be addressed by the League of Nations involved the conflict between Sweden and Finland over the sovereignty of the Åland Islands, where most of the population supported affiliation with Sweden. The League of Nations decided that the islands would belong to Finland, but would practice self-rule. Branting’s show of loyalty in accepting the League’s decision won him great respect.

“No nation is so great as to be able to afford, in the long run, to remain outside an increasingly universal League of Nations.”

Hjalmar Branting, Nobel Prize lecture, 19 June 1922

Learn more

The «father» of socialism in Sweden, Karl Hjalmar Branting was born in Stockholm, the only child of Professor Lars Branting, one of the principal developers of the Swedish school of gymnastics …

Disclaimer: Every effort has been made by the publisher to credit organisations and individuals with regard to the supply of photographs. Please notify the publishers regarding corrections.

Hjalmar Branting – Photo gallery

1 (of 1) Swedish social democrats (and father and son) Georg and Hjalmar Branting working on a translation of a book in 1916.

Unknown photographer, public domain via Wikimedia Commons. Source: Vecko-Journalen (Swedish weekly magazine) no. 52 1916.

Christian Lange – Other resources

Links to other sites

‘First Secretary of Peace’ – an article about Christian Lous Lange from Nobel Peace Center

Hjalmar Branting – Nobel Lecture

English

Swedish

Nobel Lecture*, June 19, 1922

(Translation)

Fraternity among Nations

In the fundamental clauses of the Nobel testament concerning the Peace Prize, it is stated that it should be awarded to the men or women who have sought to work for “fraternity among nations, for the abolition or reduction of standing armies and for the holding and promotion of peace congresses”.

“Fraternity among nations” is placed first. It sets forth the great goal itself. The other points cover some of the prerequisites and methods of attaining this end, expressed in the light of the striving and longing which prevailed at the time the testament was drawn up. The formulation itself mirrors a particular epoch in history. Fraternity among nations, however, touches the deepest desire of human nature. It has stood as an ideal for some of the most highly developed minds for a millennium; yet in spite of all the progress of civilization, nobody can step forward today and claim with any certainty that this goal will be reached in the near future. However unnoticed before, the clefts and gulfs lying between nations were fully exposed and deepened even further by the World War1. And the courageous work of bridging these gaps across the broken world has scarcely been begun.

No matter how far off this high goal may appear to be, no matter how violently shattered may be the illusion entertained at times by many of us that any future war between highly civilized nations is as inconceivable as one between the Scandinavian brothers, we may be certain of one thing: that for those who cherish humanity, even after its relapse into barbarism these past years, the only road to follow is that of the imperishable ideal of the fraternity of nations.

I am sure that I do not, in this connection, have to deal in any detail with the subject of nationalism and internationalism. The sort of internationalism which rejects the sovereignty of a nation within its own borders and which aims ultimately at its complete obliteration in favor of a cosmopolitan unity, has never been other than a caricature of the true international spirit. Even when supported by quotations out of context – for example, by the well-known words of the Communist Manifesto2, “The worker has no fatherlands, or by those of Gustave Hervé who, before becoming violently nationalistic during the war, exhorted French workers to plant the French flag on a dunghill3 – even then, such ideas have found no real roots in the spirit of people anywhere.

The kind of support encouraged by such modes of expression has always arisen basically from confusing the fatherland itself with the social conditions which happened to prevail in it. How often, recalls Jaurès4 in his book The New Host [L’Armée nouvelle], have the socially and politically privileged believed or pretended to believe that their own interests coincided with those of the fatherland: “The customs, traditions, and the primitive instinct of solidarity which contribute to the formation of the concept of patriotism, and perhaps constitute its physiological basis, often appear as reactionary forces. The revolutionaries, the innovators, the men who represent a higher law have to liberate a new and superior nation from the grip of the old… When the workers curse their native country, they are, in reality, cursing the social maladjustments which plague it, and this apparent condemnation is only an expression of the yearning for the new nation.”

Who can now deny, after the experiences of the World War, that this view was correct! The contradiction between nationalism and internationalism, which appears so stark when seen in the light of a warped and one-sided exposition of the duties and significance of each,. is in reality non-existent. “The same workers,” wrote this great man, “who now misuse paradoxical phrases and hurl their hatred against the very concept of a fatherland, will rise up to a man the day their national independence is in danger.” Prophetic words, confirmed on both sides of the battlefront; yet, it had actually been supposed, before any issue was at stake, that the countries on both sides could be invaded with impunity.

It is precisely this deeply rooted feeling for the importance of the nation that later becomes the basis and starting point for true internationalism, for a humanity built not of stateless atoms but of sovereign nations in a free union.

As a result of the World War and of a peace whose imperfections and risks are no longer denied by anyone, are we not even further away from the great aspirations and hopes for peace and fraternity than we were one or two decades ago?

I have already mentioned that recent years have brought with them much disillusionment concerning what has so far been achieved by humanity. But it is possible that, in the days ahead, these years we have lived through may eventually be thought of simply as a period of disturbance and regression.

The signs of renewal are far too numerous and promising to allow of despair. Never since the dawn of history, with its perpetual wars between wild tribes, never up to the present day throughout the unfolding of the ages, during which wars and devastation have occurred with such frequency and with interruptions for only such short periods of peace and recovery, never has our race experienced such a concentrated period of disturbance or such devastation of a large part of the world as that which began in 1914.

Yet in spite of the unique extent of the devastation, we should not forget that this hard labor constituted the birthpangs of a new Europe. Three great military monarchies based essentially on a feudal order have collapsed5 and been replaced by states whose constitutions assert more strongly than ever before the principles of nationality and of a people’s right to self-determination. We must remember that the people for whom this change represents a first taste of freedom and a new and brighter future did not allow their resolution to falter, no matter how great the suffering by which they bought this independence. On our own eastern frontiers where we have witnessed with joy the birth of a free Finland6; down along the Baltic coast with its three new Baltic states7; throughout the newly risen Poland, land of martyrs of freedom8; in Czechoslovakia, the fatherland of John Huss and Comenius9; and in all of southeast Europe’s more or less reconstituted states – in all of these, we have rich additions, for each of them will now enjoy a great opportunity to develop nationally, to the ultimate benefit of all that part of the world which we can call our own!

I do not overlook the fact that the appearance of these new, free nations in the European political community not only celebrates the return of the prodigal son but also creates new sources of friction here and there. There is all the more reason, therefore, to concentrate on the other great benefit which has resulted from the past years of darkness: the beginning development of a League of Nations in which disputes between members are to be solved by legal methods and not by the military superiority of the stronger.

It is a commonplace that the League of Nations is not yet-what its most enthusiastic protagonists intended it to be. The absence of President Wilson’s own country10 and of the great, though vanquished, nations, Germany and Russia11, so obviously circumscribes its ability to fulfill its task that when its critics speak of the League as a League of the Victorious Powers, they do so with some justification. Even with its faults, which can and must be remedied if our civilization is to survive, the League of Nations is succeeding – for the first time after a huge military catastrophe – in opening perspectives of a durable peace and of justice between the free and independent nations of the world, both large and small.

It is remarkable to see how Alfred Nobel’s fundamental ideas reappear in the Covenant of the League of Nations. I have already quoted from his testament, with reference to the road leading toward fraternity among nations; namely, reduction in armaments and promotion of peace congresses. The reduction of armaments is positively enjoined throughout Article 8, although in cautious terms. And the annual meetings of the League’s Assembly are in effect official peace congresses binding on the participating states to an extent that most statesmen a quarter of a century ago would have regarded as utopian. But the similarities in their respective lines of thought go even further. In her lecture here in Oslo in 1906, Bertha von Suttner quoted12 from a private communication addressed to her by Alfred Nobel: “It could and should soon come to pass that all states pledge themselves collectively to attack an aggressor. That would make war impossible and would force even the most brutal and unreasonable Power to appeal to a court of arbitration, or else keep quiet. If the Triple Alliance included every state instead of only three, then peace would be assured for centuries.”

Here we encounter the idea of sanctions in an acutely sharp form. Article 16 of the Covenant fortunately contains a considerably toned down version of it. Last year, the Assembly of the League, as a result of the initiative taken by the Scandinavian nations, further limited and clarified all the provisions of the clause prescribing the duty of states to participate in sanctions. But Nobel’s basic idea has been realized. The whole collective force of the League is to be turned against the aggressor, with more or less pressure according to the need. Without envisaging any supranational organization, for which the time is not yet ripe, the present approach is as analogous as circumstances permit to that of an earlier age when the state first exercised authority over individual leaders unaccustomed to recognizing any curbs on their own wills.

These last observations about a League comprising all states instead of only a few, should encourage us even today to remain firm in the demand which we small, so-called neutral countries should make at Geneva and everywhere: the demand that the League of Nations become universal in order truly to fulfill its task.

No nation is so great as to be able to afford, in the long run, to remain outside an increasingly universal League of Nations. However, in the nature of things, the smaller states have a special reason for doing all they can to promote its existence and development.

The equality among all members of the League, which is provided in the statutes giving each state only one vote, cannot of course abolish the actual material inequality of the powers concerned. The great powers which, from various motives, direct the development of the world toward good or evil, either forging the links of a higher concept of humanity or pandering to the greed of the few, will always exert an influence far greater than their individual votes, regardless of any permanent support they may or may not receive from the votes of dependent states. A formally recognized equality does, however, accord the smaller nations a position which they should be able to use increasingly in the interest of humanity as a whole and in the service of the ideal. The prerequisite is merely that they try as far as possible to act in unison.

We here in the North have for many years had a natural tendency to feel that when our representatives come together at an international meeting, we embark on the quest of mutual understanding and support. In this quest, there has truly been no desire on the part of any one of us to encroach upon the freedom of the others to use their own ways of thinking in arriving at the opinions they wish to hold. No one who has shared this experience, however, has failed to sense that considerable strength arose out of our coalition. It has, moreover, fortunately been the rule, at any rate recently, that the views of the spokesmen for our three peoples have essentially coincided.

Furthermore, the nature of European problems has not infrequently extended our agreement beyond the confines of the North. Other nations, not involved in the World War, have held very similar views on the measures to be taken to ensure better times. This identity of views has of itself led to the creation of a considerable coalition of powers who were neutral during the war. At Geneva, the neutral states were often in agreement concerning the preliminaries for Genoa, and Genoa itself was marked by a quite natural mutual exchange of ideas13. This unity of approach to the problem confronting us had become so much a matter of course in other conferences of powers, that the “neutrals”, as we were still called, were specially represented in the most important subcommittee.

As long as the problem of world reconstruction remains the center of interest for all nations, blocs having similar attitudes will form and operate even within the League itself. There is no reason why agreement on particular points should not be both possible and advantageous to the so-called neutrals and to one or more of the blocs, either existing or in the process of formation, within the League of Nations. With Finland and with the Baltic states we in the North have strong cultural affinities; the states of the Little Entente14 often advance views that differ from the unilateral ones of the great powers; and the representatives of the South American nations are likewise evincing a strong tendency to act together. All in all, the League of Nations is not inevitably bound, as some maintain from time to time, to degenerate into an impotent appendage of first one, then another of the competing great powers. If we all do our best to work for that real peace and reconciliation between peoples which it is our first duty to promote within the League of Nations, then the power to command attention will be available to us, even though, as small nations, we are so isolated and powerless that individually we can exert little influence on the great powers in world politics.

Allow me one other observation. The League of Nations is not the only organization, albeit the most official, which has inscribed the maintenance of peace through law on its banner. Before the war there were many who were more or less ignorant of the international labor movement but who nevertheless turned to it for salvation when the threat of war arose. They hoped that the workers would never permit a war.

We now know that this hope was futile. The World War broke out with such elemental violence, and with such resort to all means for leading or misleading public opinion, that no time was available for reflection and consideration. But after all those horrors, does it follow that the present sentiment of the workers against war, now more widely held, will exhibit the same impotence in every new situation? To be sure, the political International is at present weakened by the split which Bolshevism has caused in the ranks of labor everywhere15, but the trade-union International at Amsterdam16 is stronger than ever before. Its twenty million workers are a force to be reckoned with, and their propaganda against war and the danger of war continues ceaselessly among the masses. Some years hence it may well turn out that when the question is asked, Who has in the recent past done most for the cause of peace in the spirit of Alfred Nobel? The answer may be: The Amsterdam International.

Let us return, however, to the League of Nations. To create an organization which is in a position to protect peace in this world of conflicting interests and egotistic wills is a frighteningly difficult task. But the difficulties must not hold us back. I conclude with a few lines from James Bryce17, which could be said to epitomize the testament of this venerable champion of peace and humanity:

“The obstacles are not insuperable. But whatever they may be, we must tackle them head on, for they are much less than the dangers which will continue to menace civilization if present conditions continue any longer. The world cannot be left where it is at present. If the nations do not try to annihilate war, then war will annihilate them. Some kind of common action by all states who set a value on peace is a compelling necessity, and instead of shrinking from the difficulties, we must recognize this necessity and then go forward.”

* This lecture was delivered in the Auditorium of the University of Oslo. The translation is based on the Swedish text published in Les Prix Nobel en 1921-1922. The lecture is not given a title in Les Prix Nobel; the one provided here embodies in a phrase its central theme.

2. The basic formulation of Marxist communism written by Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels (1848).

3. Gustave Hervé (1871-1944), French journalist and founder of the socialist journal La Guerre Sociale (1908), left the Socialist Party after the outbreak of WWI, changed his journal’s name to La Victoire, supported Clemenceau’s policies.

4. Jean Léon Jaurès (1859-1914), French Socialist leader; editor of L’Humanité (1904-1914).

5. The laureate probably refers to Austria-Hungary, Germany, and Russia.

6. Russia recognized Finland’s independence early in 1918.

7. Lithuania, Latvia, and Estonia.

8. A Polish republic was proclaimed in 1918.

9. Czechoslovakia became an independent republic in 1918. John Huss [Jan Hus] (1369?-1415), religious reformer. John Amos Comenius [Jan Amos Komenský] (1592-1670), theologian and educational innovator.

10. Thomas Woodrow Wilson (1856-1924), recipient of the Nobel Peace Prize for 1919. The U.S. Senate, objecting to certain articles in the League Covenant, voted against ratification, and the U.S. never joined the League.

11. Germany eventually gained admission in 1926; Russia joined in 1934.

12. Bertha von Suttner (1843-1914), recipient of the Nobel Peace Prize for 1905. See pp. 85-86 of this volume for the quotation.

13. The international Genoa Conference, to which the laureate was a Swedish delegate. was held in the spring of 1922 to consider the economic reconstruction of Europe.

14. An alliance formed after WWI by Czechoslovakia, Yugoslavia, and Rumania.

15. In 1921 the international labor movement had been split politically into three Internationals: the Second International, revived in 1919 after WWI; the Third International (Communist), formed in 1919 in Moscow; and the so-called Vienna International, newly created in 1921 by parties which had left the Second International but were not prepared to join the Third International.

16. The International Federation of Trade Unions, founded in 1919 with headquarters at Amsterdam, replaced the old organization of the same name which had disintegrated during WWI.

17. James Bryce (1838-1922), English historian, statesman, and jurist.

The Nobel Foundation's copyright has expired.Christian Lange – Nobel Lecture

English

Norwegian

Nobel Lecture*, December 13, 1921

(Translation)

Internationalism

I

In accordance with the Statutes of the Nobel Foundation, every prizewinner is supposed to deliver a public lecture on the work which earned him the prize. It has seemed natural for me, when fulfilling this obligation today, to try to give an account of the theoretical basis of the work which is being done for international peace and law, work of which my efforts form a part. It is probably superfluous to mention that this account is not original in any of its details; it must take its material from many fields in which I am only a layman. At best it can claim to be original only in the manner in which the material is assembled and in the spirit in which it is given.

I shall discuss Internationalism, and not “Pacifism”. The latter word has never appealed to me – it is a linguistic hybrid, directing one-sided attention to the negative aspect of the peace movement, the struggle against war; “antimilitarism” is a better word for this aspect of our efforts. Not that I stand aside from pacifism or antimilitarism; they constitute a necessary part of our work. But I endow these words with the special connotation (not universally accepted) of a moral theory; by pacifism I understand a moral protest against the use of violence and war in international relations. A pacifist will often – at least nowadays – be an internationalist and vice versa. But history shows us that a pacifist need not think internationally. Jesus of Nazareth was a pacifist; but all his utterances, insofar as they have survived, show that internationalism was quite foreign to him, for the very reason that he did not think politically at all; he was apolitical. If we were to place him in one of our present-day categories, we should have to call him an antimilitarist and an individualistic anarchist.

Internationalism is a social and political theory, a certain concept of how human society ought to be organized, and in particular a concept of how the nations ought to organize their mutual relations.

The two theories, nationalism and internationalism, stand in opposition to each other because they emphasize different aspects of this question. Thus, they often oppose each other on the use of principles in everyday politics, which for the most part involve decisions on individual cases. But there is nothing to hinder their final synthesis in a higher union – one might say in accordance with Hegel’s dialectic1. On the contrary. Internationalism also recognizes, by its very name, that nations do exist. It simply limits their scope more than one-sided nationalism does.

On the other hand, there is an absolute conflict between nationalism and cosmopolitanism. The latter looks away from and wants to remove national conflicts and differences, even in those fields where internationalism accepts, and even supports, the fact that nations should develop their own ways of life.

II

Like all social theories, internationalism must seek its basis in the economic and technical fields; here are to be found the most profound and the most decisive factors in the development of society. Other factors can play a role – for example, religious beliefs, which have often influenced the shaping of societies, or intellectual movements – but they are all of subsidiary importance, and sometimes of a derivative, secondary nature. The most important factors in the development of society are, economically, the possibility of a division of labor, and technically, the means of exchanging goods and ideas within the distribution system – in other words the degree of development reached by transport and communications at any particular time.

From ethnography and history we can discern three stages in the development of social groups, limited by the possibilities provided through economic and technical development: the nomadic horde whose members live from hand to mouth; the rural community (county) or city-state where the scope of the division of labor is restricted; the territorial state and the more or less extensive kingdom in which the division of labor and the exchange of goods reach larger proportions. Every time economic and technical development takes a step forward, forces emerge which attempt to create political forms for what, on the economic-technical plane, has already more or less become reality. This never comes about without a struggle. The past dies hard because the contemporary political organizations or holders of power seldom bend themselves willingly to the needs of the new age, and because past glories and traditions generally become transformed into poetic or religious symbols, emotional images, which must be repudiated by the practical and prosaic demands of the new age. Within each such social group, a feeling of solidarity prevails, a compelling need to work together and a joy in doing so that represent a high moral value. This feeling is often strengthened by the ruling religion, which is generally a mythical and mystical expression of the group feeling. War within the group is a crime, war against other groups a holy duty.

Today we stand on a bridge leading from the territorial state to the world community. Politically, we are still governed by the concept of the territorial state; economically and technically, we live under the auspices of worldwide communications and worldwide markets.

The territorial state is such an ancient form of society – here in Europe it dates back thousands of years – that it is now protected by the sanctity of age and the glory of tradition. A strong religious feeling mingles with the respect and the devotion to the fatherland.

The territorial state today is always ready to don its “national” costume: it sees in national feeling its ideal foundation. Historically, at least in the case of the older states, nationalism, the fatherland feeling, is a product of state feeling. Only recently, during the nineteenth century, and then only in Europe, do we meet forms of the state which have been created by a deliberate national feeling. In particular, the efforts to reestablish peace after the World War have been directed toward the formation of states and the regulation of their frontiers according to a consciously national program.

It is characteristic that this should take place just when it is becoming more and more clear to all who think about the matter, that technically and economically we have left the territorial state behind us. Modern techniques have torn down state frontiers, both economical and intellectual. The growth of means of transport has created a world market and an opportunity for division of labor embracing all the developed and most of the undeveloped states. Thus there has arisen a “mutual dependence” between the world’s different peoples, which is the most striking feature of present-day economic life. Just as characteristic, perhaps, is the intellectual interdependence created through the development of the modern media of communication: post, telegraph, telephone, and popular press. The simultaneous reactions elicited all over the world by the reading of newspaper dispatches about the same events create, as it were, a common mental pulse beat for the whole of civilized mankind. From San Francisco to Yokohama, from Hammerfest to Melbourne, people read at the same time about the famine in Russia, about the conference in Washington, about Roald Amundsen’s trip to the North Pole2. They may react differently, but they still react simultaneously.

The free trade movement in the middle of the last century represents the first conscious recognition of these new circumstances and of the necessity to adapt to them. Some years before the war, Norman Angell coined the word “interdependence”3 to denote the situation that stamps the economic and spiritual culture of our time, and laid down a program for internationalism on the political level.

Inherent in the very idea of politics is the notion that it must always “come after”. Its task is to find external organizational forms for what has already been developed as a living reality in the economic, technical, and intellectual fields. In his telegram to the Nobel Committee recently, Hjalmar Branting4 formulated the task of internationalism in exactly the right words when he described it as “working toward a higher form of development for world civilization”.

The World War showed how very necessary it is that this work be brought to a victorious conclusion. It is a matter of nothing less than our civilization’s “to be or not to be”. Europe cannot survive another world war.

Moreover, if the territorial state is to continue as the last word in the development of society, then war is inevitable. For the state by its nature claims sovereignty, the right to an unlimited development of power, determined only by self-interest. It is by nature anarchistic. The theoretically unrestricted right to develop power, to wage war against other states, is antisocial and is doubly dangerous, because the state as a mass entity represents a low moral and intellectual level. It is an accepted commonplace in psychology that the spiritual level of people acting as a crowd is far lower than the mean of each individual’s intelligence or morality. Therefore, all hope of a better future for mankind rests on the promotion of “a higher form of development for world civilization”, an all-embracing human community. Are we right in adopting a teleological viewpoint, a belief that a radiant and beneficent purpose guides the fate of men and of nations and will lead us forward to that higher stage of social development? In propaganda work we must necessarily build upon such an optimistic assumption. Propaganda must appeal to mankind’s better judgment and to the necessary belief in a better future. For this belief, the valley of the shadow of death is but a war station on the road to the blessed summit.

But teleological considerations can lead no further than to a belief and a hope. They do not give certainty. History shows us that other highly developed forms of civilization have collapsed. Who knows whether the same fate does not await our own?

III

Is there any real scientific basis for the concept of internationalism apart from the strictly sociological approach?

For thousands of years, prophets and thinkers have pointed to the unity of mankind as constituting such a basis. The idea was developed in theory by the Greek philosophers, especially by the Stoics, and from them early Christianity took it up as a moral-religious principle, preaching the doctrine of God as the universal father, and that of the brotherhood of man. The idea was revived as a confirmed maxim at the beginning of more recent times by a number of writers – among them, the heretical Sebastian Franck5, the Jesuit Suárez, one of the founders of modern international law6, and Amos Comenius, the last bishop of the Moravian Brethren and the father of modern teaching. With Comenius, the concept actually acquires a physiological tinge when he writes: “Thus we human beings are like a body which retains its individuality throughout all its limbs.”7 Thereafter, the idea was kept alive in Western cultures. It dominated the leading minds during the seventeenth, eighteenth, and nineteenth centuries, from William Penn and Leibnitz to Wergeland and Emerson8.

In recent times, biology has found a totally rational and genuinely scientific basis for the concept. The unity of mankind is a physiological fact. It was the German Weismann’s9 study of jellyfish (1883) that opened the approach to such an understanding. Other scholars went on to prove that the law which Weismann had applied to jellyfish applied equally to all species of animals, including man. It is called the law of “continuity of the germ plasm”.

Upon the union of the male germ cell with the female egg cell, a new cell is created which almost immediately splits into two parts. One of these grows rapidly, creating the human body of the individual with all its organs, and dies only with the individual. The other part remains as living germ plasm in the male body and as ova in the female. In this way there live in each one of us actual, tangible, traceable cells which come from our parents and from their parents and ancestors before them, and which – through conception – can in turn become our children and our children’s children. Each of us is, literally and physiologically, a link in the big chain that makes up mankind.

All analogies break down at some point. And yet it seems to me appropriate to look upon mankind as a mighty tree, with branches and twigs to which individuals are attached as leaves, flowers, and fruit. They live their individual, semi-independent lives; they

Wake, grow and live,

Change, age and die.10

The tree, however, remains and continues, with its branches and twigs and shoots, and with constantly renewed leaves, flowers, and fruit. The latter have their small, short, personal lives. There are leaves that wither and fall unnoticed to the ground; there are flowers which gladden with their scent and color; there are fruits which can give nourishment and growth. Leaves, flowers, and fruit come and go in countless numbers; they establish connections with each other so that a net, with innumerable intersections, embraces the whole tree. It is at this point that our analogy breaks down – but the tree is one, and mankind is one single organism.

During the World War, two natural scientists, independently but with the same purpose in mind, developed and clarified the significance for internationalism of this biological conception11. Their work, especially the second author’s application of the theory, with which many natural scientists disagree, need not concern us here. Of sole use to us is the fact on which it is based. I wish only to draw a single conclusion: if mankind is a physiological entity, then war-international war no less than civil war – is suicide, a degradation of mankind. Hence, internationalism acquires an even stronger support and a firmer foundation to build on than that which purely social considerations can give.

IV

The consequences and applications of the theory of internationalism, as it is here defined and supported, are not difficult to establish. They appear in the economic and political fields. But their fundamental importance in the purely spiritual fields is limited.

Economically, the consequences of internationalism are obvious and have already been hinted at. The main concept is that of an international solidarity expressed in practice through worldwide division of labor: free trade is the principal point in the program of internationalism. This also agrees with the latest ideas and theories in the field of natural science. Concord, solidarity, and mutual help are the most important means of enabling animal species to survive. All species capable of grasping this fact manage better in the struggle for existence than those which rely upon their own strength alone: the wolf, which hunts in a pack, has a greater chance of survival than the lion, which hunts alone. Kropotkin12 has fully illustrated this idea with examples from animal life and has also applied it to the social field in his book Mutual Aid (1902).

It is necessary to linger in a little more detail over the political consequences of internationalism. Here the task is to devise patterns of organization for the concept of world unity and cooperation between the nations. That, in a word, is the great and dominating political task of our time.

Earlier ages fortified themselves behind the sovereign state, behind protectionism and militarism. They were subject to what Norman Angell called the “optical illusion” that a human being increased his stature by an inch if the state of which he was a citizen annexed a few more square miles to rule over, and that it was beneficial for a state to be economically self-supporting, in the sense that it required as few goods as possible from abroad. This national protectionism was originally formulated by the American Alexander Hamilton13, one of the fathers of the United States Constitution; it was then transplanted by the German Friedrich Lists14 from American to European soil where it was converted to use in the protectionist agitation in all the European countries.

Hand in hand with nationalist economic isolationism, militarism struggles to maintain the sovereign state against the forward march of internationalism. No state is free from militarism, which is inherent in the very concept of the sovereign state. There are merely differences of degree in the militarism of states. A state is more militaristic the more it allows itself to be guided by considerations of military strategy in its external and internal policies. The classic example here is the Prussian-German kaiser-state before, and especially during, the World War. Militarism is basically a way of thinking, a certain interpretation of the function of the state; this manner of thinking is, moreover, revealed by its outer forms: by armaments and state organization.

It is against this concept of the sovereign state, a state isolated by protectionism and militarism, that internationalism must now engage in decisive battle. The sovereign state has in our times become a lethal danger to human civilization because technical developments enable it to employ an infinite number and variety of means of destruction. Technology is a useful servant but a dangerous master. The independent state’s armaments, built up in a militaristic spirit, with unlimited access to modern methods of destruction, are a danger to the state and to others. From this point of view we can see how important work for disarmament is; it is not only a task of economic importance, which will save unproductive expenditure, but also a link in the efforts to demilitarize – or we might say, to civilize – the states, to remove from them the temptation to adopt an arbitrary anarchical policy, to which their armaments subject them.

If the sovereign state were supported only by the narrow, self-serving ideas embodied in economic isolationism and militarism, it would not be able to count on a secure existence, for internationalism could wage a fairly effective fight against it. But the sovereign state is also sustained by a spiritual principle: it claims to be “national”, to represent the people’s individuality as a distinct section of mankind.

It has already been said that in most states the “nation” is a product of the state, not the basis for the creation of the state. And when it is asserted that these “nations” have anthropological character of their own, a “racial” character, the answer must be that the state which is inhabited by an anthropologically pure race is yet to be found. Scientific investigations prove that there is in all countries an endless crossbreeding between the various constituents of the population. A “pure race” does not exist at all. Furthermore, although various external anthropological distinctions – the shape of the head, the hair, the color of skin – are exact enough in themselves, we cannot prove that any intellectual or spiritual traits are associated with them.

And “nationality” is nothing if not a spiritual phenomenon. Renan has given the valid definition: “A nation is a part of mankind which expresses the will to be a nation; a nation’s existence is a continuous, daily plebiscite – un plébiscite de tous les jours.”15 The first clause is a circular definition. It is both sharply delimited and totally exhaustive because it puts the emphasis on the will to be a nation. The concept of nationality thus moves into the realm of the spiritual. There it belongs, and there it should stay.

Internationalism will not eradicate these spiritual distinctions. On the contrary, it will develop national characteristics, protect their existence, and free their development. Internationalism differs in this from cosmopolitanism. The latter wants to wipe out or at least to minimize all national characteristics, even in the spiritual field. Internationalism on the other hand admits that spiritual achievements have their roots deep in national life; from this national consciousness art and literature derive their character and strength and on it even many of the humanistic sciences are firmly based.

Diversity in national intellectual development, distinctive character in local self-government – both of these are wholly compatible with inter-nationalism, which indeed is really a prerequisite for a rich and varied development.

It is the political authority over common interests that internationalism wants to transfer to a common management. Thus, a world federation, in which individual nations linked in groups can participate as members, is the political ideal of internationalism. Before the war, a first groping step was taken in this direction with the work at The Hague16. The League of Nations marks the first serious and conscious attempt to approach that goal.

V

A definition of internationalism along the lines which have here been discussed could take the following form:

Internationalism is a community theory of society which is founded on economic, spiritual, and biological facts. It maintains that respect for a healthy development of human society and of world civilization requires that mankind be organized internationally. Nationalities should form the constitutive links in a great world alliance, and must be guaranteed an independent life in the realm of the spiritual and for locally delimited tasks, while economic and political objectives must be guided internationally in a spirit of peaceful cooperation for the promotion of mankind’s common interests.

VI

One last word.

Has this theory of internationalism any relevance to our religious needs, to the claim to eternity that irresistibly arises in the soul of every thinking and feeling person?

There are surely many of us who can only regard the belief in personal immortality as a claim which must remain unproved – a projection of the eternity concept onto the personal level.

Should we then be compelled to believe that the theory of materialism expressed in the old Arab parable of the bush whose leaves fall withered to the ground and die without leaving a trace behind, truly applies to the family of man?

It seems to me that the theory of mankind’s organic unity and eternal continuity raises the materialistic view to a higher level.

The idea of eternity lives in all of us. We thirst to live in a belief which raises our small personality to a higher coherence – a coherence which is human and yet superhuman, absolute and yet steadily growing and developing, ideal and yet real.

Can this desire ever be fulfilled? It seems to be a contradiction in terms.

And yet there is a belief which satisfies this desire and resolves the contradiction.

It is the belief in the unity of mankind.

* Dr. Lange delivered this lecture at the Norwegian Nobel Institute in Oslo. This translation is based on the Norwegian text in Les Prix Nobel en 1921-1922.

1. Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel (1770-1831), German philosopher in whose view a concept (thesis) interacts with another concept (antithesis) to form a new concept (synthesis) which in turn becomes a new thesis.

2. The Russian famine of 1921-1922, the Washington Conference on naval armaments and Far-Eastern questions (November 12, 1921-February 6, 1922), and the Arctic expedition of the Norwegian explorer, Roald Amundsen (1872-1928), were all in the news at the time of the laureate’s lecture.

3. Norman Angell (1872-1967), recipient of the Nobel Peace Prize for 1933, in The Great Illusion (1910).

4. Hjalmar Branting (1860-1925), co-recipient, with Lange, of the Peace Prize for 1921.

5. Sebastian Franck [Franck von Wörd] (1499?-1543), German free thinker and religious writer who left Catholic priesthood to join the Lutheran Church but later separated from it.

6. Francisco Suárez (1548-1617), Spanish theologian and scholastic philosopher who refuted the patriarchal theory of government.

7. John Amos Comenius (1592-1670), Czech theologian and educational innovator; the quotation is from his Panegersia (1645).

8. William Penn (1644-1718), English Quaker and founder of Pennsylvania in North America. Baron Gottfried Wilhelm von Leibnitz (1646-1716), German philosopher and mathematician. Henrik Arnold Wergeland (1808-1845), Norwegian poet, playwright, and patriot. Ralph Waldo Emerson (1803-1882), American essayist, poet, and philosopher.

9. August Weismann (1834-1914), German biologist.

10. “vekkes, spirer og födes,/skifier, eldes og dödes.”

11. Chalmers Mitchell, Evolution and the War (London, 1915). G.F. Nicolai, Die Biologie des Krieges (2nd ed., Zurich, 1919; the second edition, but not the first, was supervised by the author himself).

12. Prince Peter Alexeivich Kropotkin (1842-1921), Russian geographer, social phi-losopher, and revolutionary.

13. Alexander Hamilton (1757?-1804), first U.S. secretary of the treasury (1789-1795).

14. Georg Friedrich List (1789-1846), German born economist, naturalized American citizen who returned to Germany as U.S. consul.

15. Ernest Renan (1823-1892), French philologist, historian, and philosopher; the quotation is from “Qu’est-ce que c’est qu’une nation?” (1882), a lecture delivered at the Sorbonne.

Christian Lange – Nobel Lecture

English

Norwegian

Nobelpris-foredrag holdt i Det Norske Nobelinstitutt i Kristiania, den 13 desember 1921

Internationalisme

I

Ifölge Nobelstiftelsens grunn-regler plikter hver pris-tager å holde et offentlig foredrag over det pris-belönnede arbeide. Det har forekommet mig naturlig, når jeg idag skal opfylle denne forpliktelse, å pröve på å gi en utredning av det teoretiske grunnlag for arbeidet for fred og rett mellem folkene, det arbeide hvori mine bestrebelser går in som et ledd. Det er vel overflödig å si at denne utredning ikke er original i nogen av sine enkeltheter; den må hente sitt materiale fra mange områder hvor jeg kun er en almindelig leg-mann. I det höieste kan utredningen gjöre krav på selvstendighet i sin sammenstilling av stoffet, og i den personlige farve som utredningen kan få.

Jeg taler om Internasjonalisme, ikke om »Pacifisme». Dette siste ord har aldri tiltalt mig – det er en sproglig bastard, og det forer tanken ensidig hen på den negative side ved freds-bevegelsen, på kampen mot krigen; for denne side ved våre bestrebelser er »anti-militarisme» et mere treffende navn. Ikke så at jeg tar avstand fra pacifismen eller anti-militarismen; de er nödvendige ledd i vårt strev. Men jeg legger i disse ord en særlig betydning (som dog ikke alle er enige om) av en moralsk teori; jeg forstår ved pacifisme den moralske protest mot anvendelsen av vold og krig i mellemfolkelige forhold. En pacifist vil oftest – i hvert fall i våre dager – være internasjonalist, og omvendt. Men historien viser oss dog eksempler på at pacifisten ikke behover å tenke internasjonalistisk. Jesus fra Nasaret var pacifist; men alle hans uttalelser, for så vidt som de er bevart, viser at internasjonalisme var ham ganske fremmed, allerede av den grunn at han overhodet ikke tenkte politisk; han var a-politisk. Skulde vi anbringe ham innenfor en av vår tids kategorier, måtte vi kalle ham anti-militarist og individualistisk anarkist.

Internasjonalisme er en social og politisk teori, en bestemt opfatning av hvordan det menneskelige samfund bör organiseres, særlig en opfatning av hvordan nasjonene bör ordne sine gjensidige forhold.

De to teorier, nasjonalisme og internasjonalisme, står i motsetning til hverandre, fordi de legger vekten i utviklingen på forskjellige sider av denne. De blir derfor gjerne motstandere i dagens praktiske politikk, hvor det som oftest gjelder å avgjöre enkelt-spörsmål, om anvendelse av prinsippene. Men der er intet i veien for, tvert imot, at de – man kunde fristes til å si: efter Hegelsk dialektikk – kan gå op i en höiere enhet. Internasjonalismen forutsetter likefrem, gjennem selve det navn den har antatt, at der eksisterer nasjoner. Den vil kun gi dem en mere begrenset plass enn den ensidige nasjonalisme önsker å vinne for dem.

Derimot er der en absolutt motsetning mellem nasjonalisme og kosmopolitisme. Denne ser bort fra og vil utslette de nasjonale motsetninger og forskjelligheter, også på de områder hvor internasjonalismen anerkjenner, og ennogså arbeider for, at nasjonene ska få utfolde sitt selvstendige liv.

II.

Som enhver social teori må Internasjonalismen söke sitt grunnlag på det ökonomiske og tekniske område; her finnes de dypeste og mest avgjörende faktorer for samfundsdannelse. Andre faktorer kan spille en rolle, således de religiöse overbevisninger, som ofte har virket samfunds-dannende, eller intellektuelle strömninger; men de er dog alle av underordnet betydning, og imellem av avledet, sekundær art. De viktigste faktorer i samfunds-dannelsens process er, i ökonomisk henseende, muligheten for arbeids-deling; i teknisk henseende, midlene for utveksling av varer og av ideer i fordelingens tjeneste, med andre ord den utviklings-grad som samferdsels og- meddelelses-midler til enhver tid har nådd.

Etnografi og historie viser oss en rekke trinn i social gruppering, bestemt av de muligheter som den ökonomiske og tekniske utvikling skaper: horden, hvis medlemmer lever fra hånden til munnen; bygde-samfundet (kantonet) eller by-staten, hvor arbeids-fordelingen finner sted innenfor en snever krets; den territoriale stat og det mer eller mindre vidtstrakte rike, hvor arbeids-fordelingen og vare-utvekslingen når et videre omfang. Hver gang den ökonomisk-tekniske utvikling gjor et skritt fremad, våkner der krefter, som söker å skape politiske former for det som på det ökonomisk-tekniske felt allerede mer eller mindre er blitt virkelighet. Det skjer aldri uten kamp. »The past dies hard», for tidens politiske organisasjoner eller makthavere böier sig sjelden godvillig inn under den nye tids nödvendighet, og omkring fortidens og tradisjonens makter ranker der sig gjerne poetiske eller religiöse forestillinger, sentimentale vurderinger, som frastotes av de nye tiders praktiske og nökterne krav. Uer hersker innenfor enhver sådan social gruppe en fölelse av solidaritet, en uvilkårlig trang til og glede ved samarbeide, som representerer en höi moralsk verdi; ofte styrkes fölelsen gjennem den herskende religion, som i almindelighet er et mytisk og mystisk uttrykk netop for gruppefölelsen. Krig innenfor gruppen er en forbrydelse; krig mot andre grupper en hellig plikt.

Vi står nu i overgangs-stadiet fra den territoriale stat til verdens-samfundet. Politisk beherskes tiden ennu av den territoriale stats idé; ökonomisk-teknisk lever vi i verdens-samferdselens og verdens-markedets tegn.

Den territoriale stat er så gammel som samfunds-form – her i Europa går den sine tusen år tilbake – at den nu er omgitt av alderens ærverdighet og av tradisjonens glans. Der blander sig en sterk religiös fölelse i ærbödigheten og hengivenheten for fedrenes land. Den territoriale stat klær sig i vår tid gjerne i »nasjonalt» klædebon: den ser sitt ideelle grunnlag i nasjonal-fölelsen. Historisk er dog nasjonalismen, fedrelands-fölelsen, i all fall for de eldre staters vedkommende, et produkt av stats-fölelse. Först i nyeste tid, i löpet av det 19de århundre, möter vi, og alene på europeisk grunn, statsdannelser, som er fremgått av en bevisst nasjonal-fölelse. Navnlig har fredsslutningene efter verdenskrigen sökt å ordne stats-dannelsene og regulere landenes grenser efter et bevisst nasjonalt program.

Det er karakteristisk at dette skjer samtidig med at det blir mer og mere klart for alle dem som tenker over saken, at vi i teknisk-ökonomisk henseende er kommet helt utover den territoriale stat. Den moderne teknikk har brutt ned statsgrensene både ökonomisk og intellektuellt. Den har ved sin utvikling av samferdsels-midlene skapt et verdensmarked og et arbeids-fordelings-område som omfatter alle civiliserte stats-samfund og den störste del av de uciviliserte. Derved er der opstått en «gjensidig avhengighet» mellem verdens forskjellige folkeslag som er det mest fremtredende trekk i vår tids ökonomiske liv. Fullt så karakteristisk er kanskje den intellektuelle samhörighet som skapes ved utviklingen av de moderne meddelelsesmidler, post, telegraf, telefon, populære aviser. De samtidige reaksjoner som fremkalles hele verden over ved lesningen av avisenes telegrammer om de samme begivenheter, skaper som et felles åndelig pulsslag for hele den civiliserte menneskehet. Fra San Francisko til Yokohama, fra Hammerfest til Melbourne leser folk samtidig om hungersnöden i Rusland, om konferansen i Washington, om Roald Amundsens nordpols-ferd. De reagerer forskjellig, men dog samtidig.

Frihandels-bevegelsen ved midten av det forrige århundre representerer den förste bevisste erkjennelse av disse nye forhold og av nödvendigheten av å inrette sig i overensstemmelse med dem. Nogen år for krigen formet Norman Angell1 ordet »Interdependence» som betegnelse for den tilstand som preger vår tids kultur ökonomisk og åndelig, og opstillet programmet for Internasjonalismen i politisk henseende.

Det ligger i selve politikens begrep at den altid må komme bakefter. Dens opgave er å finne de ytre organisatoriske former for det som allerede har utviklet sig som levende virkelighet på det ökonomisk-tekniske og det åndelige område. I sitt telegram til Nobelkomiteen forleden dag formet Hjalmar Branting Internasjonalismens opgave i netop de rette ord, da han betegnet den som »arbetet fram mot en högre utvecklingsform for vårldens civilisation».

Verdenskrigen viste hvor uomgjengelig nödvendig det er at dette arbeide fores frem til seier. Det gjelder intet mindre enn vår civilisasjons være eller ikke-være. En verdenskrig til kan Europa ikke overleve.

Og hvis den territoriale stat skal bli stående som samfunds-utviklingens siste ord, da er krig ikke til å undgå. Staten gjör nemlig efter sitt begrep fordring på suverenitet, rett til ubegrenset makt-utfoldelse, bestemt alene av egoistisk interesse. Den er efter sitt vesen anarkisk. Dens teoretisk sett ubegrensede rett til makt-utfoldelse, til å fore krig mot andre stater er anti-social, og den er dobbelt farlig, fordi staten som masse-vesen representerer et lavt moralsk og intellektuellt nivå. Det er en anerkjent almensetning for psykologien at hvor mennesker optrer i flok, som masse, er deres åndelige utviklings-trinn et langt lavere enn gjennemsnittet av hvert enkelt individs intelligens eller moral.

Derfor er alt håb om en bedre fremtid for menneskeheten knyttet til arbeidet for »en höiere utviklingsform for verdens civilisasjon», et alt omfattende menneskelig samfund. Har vi nu rett til å anlegge et teleologisk synspunkt, til å tro at en lys og god vilje styrer menneskenes og folkenes skjebne, og vil före oss frem til dette höiere trin av samfunds-utvikling? I propaganda-arbeidet må vi uvilkårlig bygge på en sådan optimistisk forutsetning. Propagandaen må appellere til menneskenes bedre innsikt og til den uvilkårlige tro på en bedre fremtid. For denne tro er dödens skyggers dal bare en gjennem-gangs-stasjon på veien frem til de liflige bjerge. Men den teleologiske betrakting kan ikke fore lenger enn til en tro og et håb. Nogen visshet gir den ikke. Historien viser oss at höit utviklede civilisasjons-forrner er gått til grunne. Hvem vet om ikke den samme skjebne er vår civilisasjon beskåret?

III.

Finnes der et strengt videnskabelig grunnlag for den internasjonalistiske tanke utenfor den rent sociologiske betraktning?

Seere og tenkere har i tusener av ar henvist til menneskehetens enhet som et sådant grunnlag. Den blev opstillet som teori av de greske filosofer, fremfor alt av stoikerne, og fra dem optok den eldste kristendom tanken som en moralsk-religiös grunnsetning, i læren om gud som alles far og om menneskenes brorskap. Tanken dukker op igjen som bevisst læresetning hos en rekke forfattere i begynnelsen av den nyere tid, hos den kjetterske Sebastian Franck, hos jesuiten Suarex, en av den moderne folkeretts grunnleggere, hos Amos Comenius, den siste biskop for de mähriske brödre, den moderne pedagogikks far. Hos Comenius får tanken formelig et fysiologisk anströk når han skriver: «Således er da vi mennesker som ett legeme, som horer sammen gjennem alle sine lemmer.»2 Og siden er tanken aldri död innenfor den vesterlandske kulturkrets. Den behersker de förende ånder gjennem det 17de, 18de og 19de århundre, fra William Penn og Leibnitz til Wergeland og Emerson.

I nyeste tid har biologien funnet et helt rasjonelt og reelt videnskabelig grunnlag for tanken. Menneskehetens enhet er et fysiologisk faktum. Det var tyskeren Weissmanns undersökelser over en art maneter (1883) som åpnet veien frem til denne erkjennelse. Andre lærde har vist at den lov Weissmann hadde påvist tilværelsen av for manetenes vedkommende, gjaldt for alle dyre-arter, også for menneskene. Den kalles loven om sed-plasmaets kontinuitet.

Ved foreningen mellem den mannlige sed-celle og det kvinnelige egg dannes der en ny celle, som dog straks splittes i to deler. Den ene del vokser hurtig og danner det menneskelige legeme – individet – med alle dets organer, og dör med individet. Den annen del forblir levende sed-plasma i det mannlige legeme, egg i det kvinnelige legeme. Således lever der i hver av oss, virkelig, påtagelig, påviselig, celler som er av vore foreldre, av deres foreldre og forfedre igjen, og som – gjennem befruktningen – kan bli til våre barn, og i våre barn til deres etterkommere og i deres efterkommere. Hver av oss er, rent bokstavelig og fysiologisk, et ledd i den store kjede som danner menneskeheten.

Enhver sammenligning halter. Og dog forekommer det mig treffende å se på menneskeheten som et mektig tre med grener og kvister, til hvilket individene er festet som blad, blomster og frukter. Disse förer sin individuelle, halvt selvstendige tilværelse; de

»vekkes, spirer og födes,

skifter, eldes og dödes».

Treet forblir og består, med sine grener og kvister og skudd, med stadig nye blad, blomster og frukter. De har sitt lille korte personlige liv. Der er blad som visner og faller ubemerket til jorden; der er blomster som gleder ved sin duft og sin farve; der er frukter som kan gi næring og vekst. Blad, blomster og frukter kommer og går i uoverskuelig tall; de knytter forbindelser med hverandre, så et nett med uendelige kryssninger omspender det hele tre – her er det vår sammenligning halter – men treet er ett, menneskeheten er én, og én organisme.

Under verdenskrigen har to naturforskere, hver fra sin leir, men dog med samme sikte for anvendelsen, utviklet og nærmere forklart betydningen av denne naturvidenskabelige erkjennelse for Internasjonalismen.3 Her vedkommer navnlig den siste forfatters anvendelser av teorien, som blir bestridt av mange naturvidenskabsmenn, oss ikke. Vi har bare bruk for det grunnleggende faktum. Og jeg önsker bare å trekke en eneste slutning: er menneskeheten en fysiologisk enhet, så er krig – mellemfolkelig krig ikke mindre enn borgerkrig – selvmord, en nedverdigelse av menneskeheten. Og Internasjonalismen får en dypere begrunnelse, fastere bunn å bygge på ennda, enn den som den rent sociologiske betraktning kan gi.

IV.

Konsekvensene og anvendelsene av Internasjonalismens teori som den her er utfört og begrunnet, er ikke vanskelige å trekke. De fremtrer på det ökonomiske og på det politiske område. Derimot kan de kun i begrenset grad få grunnleggende betydning på det rent åndelige felt.

I ökonomisk henseende gir Internasjonalismens konsekvenser sig av sig selv. De er allerede antydet tidligere. Hovedtanken er mellemfolkelig solidaritet satt ut i praksis gjennem en verdens-omspennende arbeids-fordeling: frihandel er et hovedpunkt på Internasjonalismens program. Dette stemmer forövrig også med de nyeste tanker og teorier på naturvidenskabelig felt. Samhold og solidaritet, gjensidig hjelp er de viktigste midler til å holde sig oppe for dyre-artene. De arter som förstår dette, klarer sig bedre i kampen for tilværelsen enn de som stoler på sin isolerte styrke: ulven som optrer i flokk, har storre chanser for å bestå enn löven, som går alene på jakt. – Denne tanke har Krapotkin utförlig belyst ved eksempler fra dyrelivet, og også overfört den på socialt felt, i sin bok »Mutual Aid» (1902).

Det er nödvendig å dvele noget utforligere ved Internasjonalismens konsekvenser på det politiske felt. Her er opgaven å finne de ytre former i organisatorisk henseende for tanken om verdens-samhold og mellemfolkelig samvirke. Det er i ett ord uttrykt vår tidsalders store, alt beherskende politiske opgave.

Den gamle tid forskanser sig bak den suverene stat, bak proteksjonisme og militarisme. Den bygger på det Norman Angell kalte den »optiske illusjon», at et menneske får en alen lagt til sin vekst, om den stat hvis borger han er får flere kvadrat-kilometer å råde over, og at det er en lykke for en stat å være ökonomisk selvhjulpen, i den forstand at den henter minst mulig varer fra utlandet. Denne nasjonale proteksjonisme blev oprindelig utformet av amerikaneren Alexander Hamilton (1757- 1804), en av fedrene for de Forenede Staters forfatning; blev så av tyskeren Friedrich List (1789-1846) overfört fra amerikansk til europeisk grunn, hvor den er blitt utmyntet i smått til bruk ved den proteksjonistiske agitasjon rundt om i alle Europas land.

Hånd i hånd med den nasjonalistiske proteksjonisme kjemper militarismen for oprettholdelsen av den suverene stat mot den frembrytende Internasjonalisme. Ingen stat er fri for militarisme; den hörer nödvendig med til den suverene stats begrep. Der er kun grader i statenes militarisme. En stat er desto mer militaristisk, jo mer den i sin ytre og indre politikk lar sig lede av militært-strategiske hensyn. Det klassiske eksempel er her den pröissisk-tyske keiser-stat forut for, og fremfor alt under, verdens-krigen. Militarisme er i sin grunn en tenkemåte, en bestemt opfatning av statens opgave; men denne tenkemåte gir sig uttrykk i ytre former: i rustninger og statsorganisasjon.

Mot den suverene stats begrep, således omgjerdet av proteksjonisme og militarisme, må Internasjonalismen nu före sin avgjörende kamp. Den suverene stat er i vår tid blitt en dödelig fare for den menneskelige civilisasjon, fordi den tekniske utvikling setter den i stand til å ta uendelige arter og mengder av ödeleggelses-midler i sin tjeneste. Også om teknikken gjelder det at den er en nyttig tjener, men en farlig herre. Ledet i militaristisk ånd, med ubegrenset adgang til de moderne ödeleggelses-midler, blir den enkelte stats rustninger en fare både for den selv og for andre. Fra dette utsiktspunkt ser vi hvilken betydning arbeidet for avrustning har: det er ikke bare et arbeide av ökonomisk rekkevidde, som vil spare uproduktive utgifter; det er et ledd i bestrebelsene for å demilitarisere – like frem oversatt: for å civilisere – statene, ta fra dem den fristelse til en egenmektig, anarkisk politikk som deres rustninger utsetter dem for.

Hvis den suverene stat alene stöttet sig til de snevert egoistiske tanker som gir sig uttrykk i ökonomisk proteksjonisme og i militarisme, vilde den nu ikke kunne regne på nogen sikker tilværelse: mot den vilde Internasjonalismen ha en forholdsvis lett kamp. Men den suverene stat stötter sig dessuten til et åndelig prinsipp: den gjör krav på å være »nasjonal», på å representere en folke-individualitet, en særlig gren av menneskeheten.

Det er for sagt at i de fleste stater er »nasjonen» et produkt av staten, ikke et grunnlag for statsdannelsen. Og når det er blitt hevdet at disse »nasjoner» skal ha et eget antropologisk preg, en »rase»-karakter, så må dertil svares at ennu er ikke den stat påvist som innen sine grenser er bebodd av en antropologisk ren rase. I alle land viser det sig, som resultat av videnskabelige undersökelser, at der finnes en uendelighet av kryssninger mellem befolknings-elementene. En »ren rase» eksisterer overhode ikke. Dertil kommer at de antropologiske skjelnemerker, hodeform, hår, hudfarve, de er vel i sig selv eksakte nok; men vi vet ikke noget om at der knytter sig åndelige karakter-trekk til hver av disse ytre antropologiske skjelnemerker.

Og »nasjonalitet» er ingenting, om den ikke er et åndelig fenomen. Renan4 har gitt den gyldige definisjon: »En najson er en del av menneskeslegten som har viljen til å være en nasjon; en nasjons tilværelse er en uavladelig daglig folkeavstemning – un plébiscite de tous les jours.» – Den förste setning synes å definere i ring. Den er dog både skarpt avgrenset og helt uttömmende, fordi den legger vekten på viljen til å være en nasjon. Og idet den det gjör, flytter den nasjonalitets-begrepet over til det åndelige felt. Der hörer det hjemme. Til det felt bör det også begrenses.

Internasjonalismen vil ingenlunde utslette dette åndelige merke. Tvertom, den vil utvikle de nasjonale eiendommeligheter og sikre deres liv og frie utfoldelse. Deri skiller Internasjonalismen sig fra kosmopolitismen. Denne vil utslette, i hvert fall utjevne, de nasjonale eiendommeligheter også på det åndelige område. Internasjonalismen derimot erkjenner at de åndelige idretter har sin rot dypt nede i nasjonalt liv; derfra suger kunst og litteratur sin eiendommelighet og sin kraft, ja også mange av åndsvidenskapene er dypt nasjonalt begrunnet.

Forskjelligartethet i den åndelige nasjonale utvikling, særpreg og eiendommelighet i stedlig selvstyre, begge deler er vel forenelig med Internasjonalismen, ja, i virkeligheten en betingelse for en rik og mangeartet utvikling.

Det er den politiske myndighet over de felles interesser som Internasjonalismen vil overföre til en felles ledelse. Derfor blir en verdensföderasjon, hvori de enkelte nasjoner, samlet i stater, kan gå inn som medlemmer, Internasjonalismens politiske ideal. Forut for krigen var der gjort et förste famlende skritt i denne retning gjennem Haag-verket. Folkenes Forbund betegner det förste alvorlige og bevisste forsok på å komme målet nær.

V.

En definisjon av Internasjonalismen efter de linjer som her er optrukket, vilde kunne formes omtrent i folgende ord:

Internasjonalismen er en samfunds-teori som bygger på ökonomiske, åndelige og biologiske kjensgjerninger. Den hevder at hensynet til en sunn utvikling av det menneskelige samfund og av verdens civilisasjon krever at menneskeheten organiseres i internasjonal form. Nasjonalitetene bör danne de konstitutive ledd i et stort verdens-forbund, og må sikres et selvstendig liv på det åndelige område og for stedlig begrensede opgaver, mens ökonomiske og politiske formål må ledes internasjonalt, i det fredelige samvirkes tegn, til fremme av menneskehetens felles interesser.

VI.

Ett ord til.

Har denne Internasjonalismens teori noget bud til vårt religiöse behov, til det evighets-krav som uimotståelig reiser sig for hver tenkende og folende menneskesjel?

Det er visselig mange av oss som kun kan opfatte troen på en personlig udödelighet som en uinnloselig fordring – en projeksjon av evighets-tanken på det personlige plan.

Skal vi så måtte böie oss for materialismens påstand, uttrykt i den gamle arabiske parabel om busken som billede på menneskenes slekt, den hvis blad faller visne til jorden og der dör, uten å efterlate sig spor?

Det forekommer mig at teorien om menneskehetens organiske enhet og evige sammenheng hever den materialistiske opfatning op i et höiere plan.

Hos oss alle lever evighets-tanken. Vi törster efter å leve på en tro som löfter vår lille personlighet op i en höiere sammenheng – en sammenheng som er menneskelig og dog over-menneskelig, absolutt og dog i stadig vekst og utvikling, ideel og dog virkelig.

Er dette ikke uopfyldelige krav? Det synes å være bare motsetninger.

Og dog finnes der en tro som tilfredsstiller kravene og löser motsetningene.

Det er troen på menneskehetens énhet.

1. »The Great Illusion » (1909/10)

3. Chalmers Mitchell, Evolution and the War, London 1915, og G. F. Nicolai, Die Bio-logie des Krieges, 3. Auflage, Xiirich 1919. (Förste utgave blev ikke besotget av forf. selv; man bör derfor bare lese 2:nen utgave.)

4. »Qu’est ce que c’est qu’une nation?» (1882).

The Nobel Foundation's copyright has expired.Hjalmar Branting – Nobel Lecture

English

Swedish

Nobel-föredrag hållet i Kristiania den 19 juni 1922

Nobelföredrag

I grundbestämmelserna för det Nobelska testamentet angives i fråga om fredspriset, att, det bör tillfalla män eller kvinnor, som sökt verka »för folkens förbrödring, för avskaffande eller minskning av de stående härarna och för åstadkommande av fredskongresser».