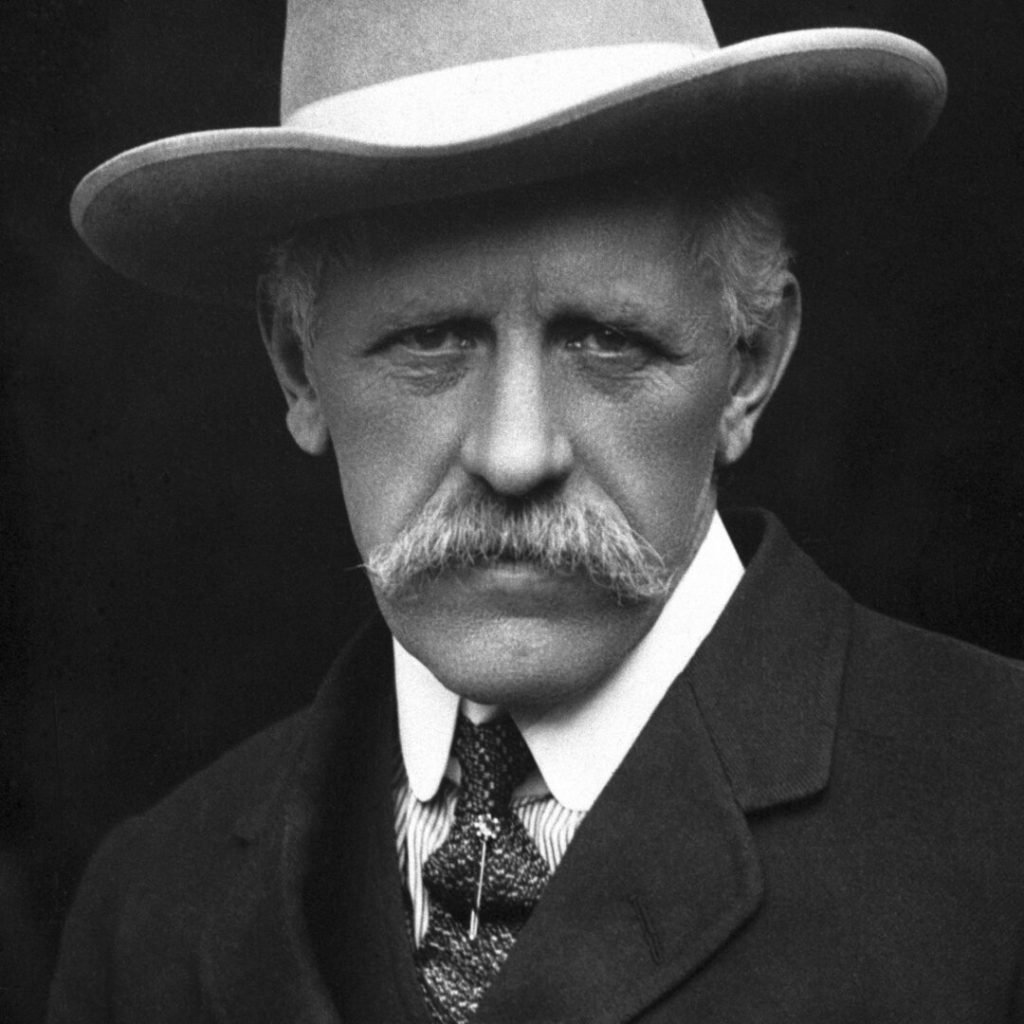

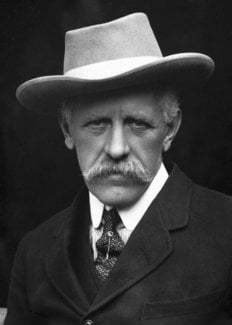

Fridtjof Nansen was born at Store Frøen, near Oslo. His father, a prosperous lawyer, was a religious man with a clear conception of personal duty and moral principle; his mother was a strongminded, athletic woman who introduced her children to outdoor life and encouraged them to develop physical skills …

Fridtjof Nansen – Speed read

Fridtjof Nansen was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize for his leading role in the repatriation of prisoners of war, in international relief work and as the League of Nations’ High Commissioner for Refugees.

Full name: Fridtjof Nansen

Born: 10 October 1861, Kristiania (now Oslo), Norway

Died: 13 May 1930, Oslo, Norway

Date awarded: 10 December 1922

Helping refugees and famine victims

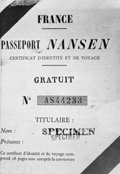

Fridtjof Nansen was a scientist, polar explorer, political activist and humanist. He earned a doctoral degree in zoology, crossed Greenland’s ice cap and endured harsh winters in the Arctic wilderness. He also actively supported Norway’s withdrawal from the union with Sweden in 1905. After WWI, Nansen oversaw the prisoner-of-war exchange between Russia, Germany and the Austro-Hungarian Empire under the auspices of the new League of Nations. He participated in relief efforts when famine broke out in the Soviet Union. In 1922 Fridtjof Nansen was named the League of Nation’s first high commissioner for repatriation of refugees. That same year, the League began to issue the “Nansen Passport” to stateless persons, enabling them to cross national borders. In his final years, Nansen dedicated himself to the cause of Armenian refugees.

”When one has stood face to face with famine, with death by starvation itself, then surely one should have had one’s eyes opened to the full extent of this misfortune.”

Fridtjof Nansen, Nobel Prize lecture, 19 December 1922.

Polar explorer and nationalist

In 1888-89 Nansen crossed Greenland’s ice cap with three other Norwegians and two Samis. A few years later he spent two winters in the Arctic wastelands in an attempt to reach the North Pole on skis. This brought him international acclaim, which proved to be useful when Norway withdrew from its union with Sweden in 1905. Nansen was strongly in favour of dissolving the union, despite Swedish views that the break was unlawful. Nansen became Norway’s leading spokesman vis-à-vis other countries. As a result of his efforts, Great Britain sent a clear message to Sweden opposing the use of force against Norway.

”What he has lived through, this man who has seen Europe’s misery at first hand and who has felt a sense of responsibility for it.”

Fredrik Stang, Chairman of the Nobel Committee, Speech, 10 December 1922.

Famine and prisoners of war

In 1920 the League of Nations appointed Nansen to direct the post-WWI exchange of 400,000 prisoners of war between Germany, the Austro-Hungarian Empire and Russia. Nansen, an extremely popular figure in Great Britain, was able to convince the British government to finance the prisoner exchange. At the same time, famine broke out in the Soviet Union, and Nansen went there to help. The Western governments were sceptical, believing that Nansen was being used as a puppet by the Communist regime. Nansen, however, remained convinced that it was not in Europe’s best interest to isolate Lenin’s new regime.

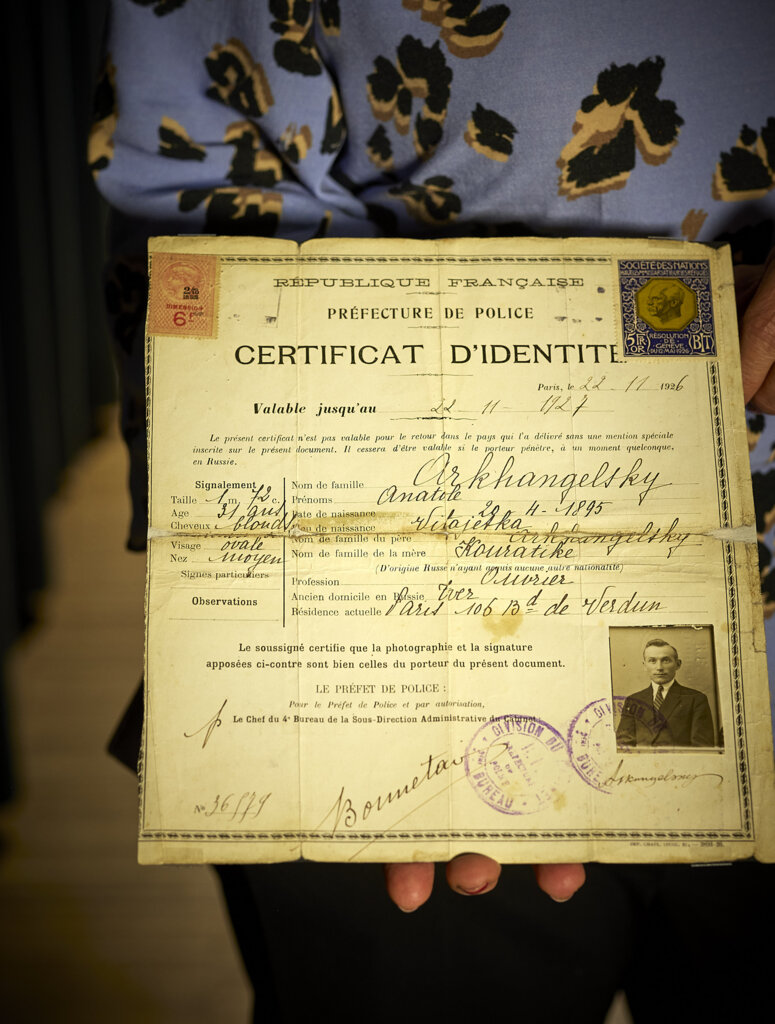

The “Nansen Passport” and Nansen as high commissioner

After the 1917 Revolution, civil war erupted in Russia. Lenin revoked the citizenship of Russians who had fled to the West after the Communist victory, thus denying them the ability to cross national borders. Nansen took the initiative to establish a special passport issued to stateless refugees, and the Red Cross proposed that it bear Nansen’s name. The League of Nations approved the “Nansen Passport” in 1922, after having appointed Nansen as high commissioner for repatriation of refugees. Much sought-after, the Nansen Passport made it possible for well-known Russians such as Igor Stravinsky, Sergey Rachmaninov, Marc Chagall and Anna Pavlova to pursue new lives in the West.

Support for the Armenians

In the late 1920s, Nansen dedicated himself to the Armenian cause. During WWI, the Allies encouraged the Armenians to rebel against the Turks, who were fighting on the side of Germany. This resulted in the tragic genocide of one million Armenians. Nansen campaigned for the establishment of a home for Armenian refugees from Turkey on the Soviet side of the border. By then, however, Stalin had assumed power, and was staunchly opposed to an independent Armenian state.

”Peace Prize laureates largely comprise a mix of opportunists, paragons of virtue and charitable benefactors. Nansen is not only one of the few winners who is truly deserving of this prize, but he has also managed to earn it in what is probably the shortest period of time.”

Roland Huntford in Fridtjof Nansen, The Man Behind the Myth. Page 537, Aschehoug 1996.

Learn more

Disclaimer: Every effort has been made by the publisher to credit organisations and individuals with regard to the supply of photographs. Please notify the publishers regarding corrections.

Fridtjof Nansen – Nobel Lecture

English

Norwegian

Nobel Lecture*, December 19, 1922

(Translation)

The Suffering People of Europe

In the Capitoline Museum in Rome is a sculpture in marble which, in its simple pathos, seems to me to be a most beautiful creation. It is the statue of the “Dying Gaul”. He is lying on the battlefield, mortally wounded. The vigorous body, hardened by work and combat, is sinking into death. The head, with its coarse hair, is bowed, the strong neck bends, the rough powerful workman’s hand, till recently wielding the sword, now presses against the ground in a last effort to hold up the drooping body.

He was driven to fight for foreign gods whom he did not know, far from his own country. And thus he met his fate. Now he lies there, dying in silence. The noise of the fray no longer reaches his ear. His dimmed eyes are turned inward, perhaps on a final vision of his childhood home where life was simple and happy, of his birthplace deep in the forests of Gaul.

That is how I see mankind in its suffering; that is how I see the suffering people of Europe, bleeding to death on deserted battlefields after conflicts which to a great extent were not their own.

This is the outcome of the lust for power, the imperialism, the militarism, that have run amok across the earth. The golden produce of the earth has been trampled under iron feet, the land lies in ruins everywhere, and the foundations of its communities are crumbling. People bow their heads in silent despair. The shrill battle cries still clamor around them, but they hardly hear them anymore. Cast out of the lost Eden, they look back upon the simple basic values of life. The soul of the world is mortally sick, its courage broken, its ideals tarnished, and the will to live gone; the horizon is hazy, hidden behind burning clouds of destruction, and faith in the dawn of mankind is no more.

Where is the remedy to be sought? At the hands of politicians? They may mean well enough, many of them at any rate, but politics and new political programs are no longer of service to the world – the world has had only too many of them. In the final analysis, the struggle of the politician amounts to little more than a struggle for power.

The diplomats perhaps? Their intentions may also be good enough, but they are once and for all a sterile race which has brought mankind more harm than good over the years. Call to mind the settlements arranged after the great wars – the Treaty of Westphalia1, the Congress in Vienna with the Holy Alliance2, and others. Has a single one of these diplomatic congresses contributed to any great extent to the progress of the world? One is here reminded of the famous words of Oxenstjerna3 to his son when he complained about the negotiations in Westphalia: “If you only knew, my son, with how little wisdom the world is ruled.”

We can no longer look to traditional leadership for any hope of salvation. We have of late experienced one diplomatic and political congress after another; has any one of these brought the solution any nearer? There is at present one in progress in Lausanne4. Let us hope that it will bring us the longed-for peace in the East so that at least one delicate question may be resolved.

But what of the main evil itself, the heart of the disease? It is whispered that France does not want to reach a final settlement with Germany, does not want Germany to finish paying her indemnities. For in that case, the pretext for occupying the western side of the Rhine would be removed, and she could no longer unsettle German industry with threats against the Ruhr district. This is naturally only malicious slander, but how common are such rumors!

It is also whispered that neither do. the industrial leaders of Germany desire a final agreement with France. They would prefer the uncertainty to continue so that the value of the mark will fall steadily, enabling German industry to survive longer. For, if a settlement were to come, then the mark would be stabilized or even rise in value, and German industry would be ruined since it would no longer be competitive.

Whether these things are true or not, the mere fact that they are uttered at all reflects the manner in which the whole European community and its way of life have been and still are toys in the hands of reckless political and financial speculators – perhaps largely bunglers, inferior men who do not realize the outcome of their actions, but who still speculate and gamble with the most valuable interests of European civilization.

And for what? Only for power. This unfortunate struggle, this appalling trampling of everything and everyone, this destructive conflict between the social classes and even between peoples exists for power alone!

When one has stood face to face with famine, with death by starvation itself, then surely one should have had one’s eyes opened to the full extent of this misfortune. When one has beheld the great beseeching eyes in the starved faces of children staring hopelessly into the fading daylight, the eyes of agonized mothers while they press their dying children to their empty breasts in silent despair, and the ghostlike men lying exhausted on mats on cabin floors, with only the merciful release of death to wait for, then surely one must understand where all this is leading, understand a little of the true nature of the question. This is not the struggle for power, but a single and terrible accusation against those who still do not want to see, a single great prayer for a drop of mercy to give men a chance to live.

Surely those who have seen at first hand the destitution pervading our misgoverned Europe and actually experienced some of the endless suffering must realize that the world can no longer rely on panaceas, paper, and words. These must be replaced by action, by persevering and laborious effort, which must begin at the bottom in order to build up the world again.

The history of mankind rises and falls like the waves. We have fallen into wave-troughs before in Europe. A similar trough occurred a hundred years ago after the Napoleonic Wars. Everyone who has read the excellent work of Worm-Müller5 describing the conditions here in Norway during that time must have noticed the many remarkable similarities between the situation then and now. It may be a consolation to know that the abyss of those times disappeared and that Norway struggled upward again; but it took a depressingly long time, thirty to forty years.

This time, as far as I can see, the trough is even deeper and more extensive, embracing the major part of Europe, and, in addition, exists under conditions that now are more complex. It is true that industry did exist at that time, but people lived off the land to a far greater extent. Now industry has come into its own, and it is more difficult to bring recovery to industry after a depression than to agriculture. A few good years will put farming back on its feet, but many years are required to develop new markets for industry. All the same, we may reasonably hope that the process of revival will be more rapid this time, for everything happens more quickly in our day because of our systems of communication and the vast apparatus of economic facilities that we now possess. But there are as yet few signs of progress. We have still not reached the bottom of the wave-trough.

What is the basic feeling of people all over Europe? There is no doubt that for a great many it is one of despair or distrust of everything and everyone, supported by hate and envy. This hatred is each day disseminated among nations and classes.

No future, however, can be built on despair, distrust, hatred, and envy.

The first prerequisite, surely, is understanding – first of all, an understanding of the cause and the nature of the disease itself, an understanding of the trends that mark our times and of what is happening among the mass of the population. In short, an understanding of the psychology of every characteristic of our apparently confused and confounded European society.

Such an understanding is certainly not attainable in a day. But the first condition for its final establishment is the sincere will to understand; this is a great step in the right direction. The continuous mutual abuse of groups holding differing views, which we witness in the newspapers, will certainly never lead to progress. Abuse convinces no one; it only degrades and brutalizes the abuser. Lies and unjust accusations achieve still less; they often finally boomerang on those who originate them.

It must also always be remembered that there is hardly a trend or movement in the community which does not in some degree possess a reason and right of its own, be it socialism or capitalism, be it fascism or even the hated bolshevism. But it is because of blind fanaticism for and against – especially against – that conflicts come to a head and lead to heartrending struggles and destruction; whereas discussion, understanding, and tolerance might have turned this energy into valuable progress.

An expansion of this subject is not possible here; suffice it to say that the parable about seeing the mote in your neighbor’s eye while not aware of the beam in your own6 is valid for all times, and not least for the age in which we live.

But when understanding is absent and especially when the will to understand is lacking, then that fermenting uncertainty, which threatens us with total destruction, arises. No one knows what tomorrow will bring. Many people live as though each day were the last, thus sliding into a state of general decadence. From this point the decline is steady and inexorable.

Moreover, the worst that this insecurity, this speculation in uncertainty, creates, is the fear of work; it was bred during the war, and it has grown steadily since. It was bred by the stock-jobbing and the speculation familiar to us all, whereby people could make fortunes in a short time, thinking they could live on them for the rest of their lives without having to work and toil. This created an aversion to work which has lasted to this very day. There are still some who will honestly and wholeheartedly settle down to hard toil, but the only places where I have met this sincere will to work are those where the angel of death by starvation is reaping his terrible harvest.

I shall always remember a day in a village east of the Volga to which only one-third of its inhabitants had returned; of the remaining two-thirds, some had fled and the rest had died of starvation. Most of the animals had been slaughtered; but courage had still not been completely extinguished, and although their prospects were bleak, the people still had faith in the future. “Give us seed”, they said, “and we will sow it in the soil.” “Yes”, we replied, “but what will you do without animals to pull the plough?” “That does not matter”, they said; “if there are no animals, we will put ourselves and our women and children to the plough.” It was not selfindulgence that was speaking here, not extravagance, not mere showmanship – it was the very will to stay alive, which had not given in.

Must we all live through the bitter pangs of hunger before we learn the real value of work?

I might also mention conditions in Germany. I have been told that because of short working hours and restricted output, Germany does not produce the coal needed for her own requirements and must therefore buy coal from England – I believe a figure of one million tons a month was mentioned – and pay for it with foreign currency. But if the working hours were increased to ten hours a day, Germany could herself produce an adequate supply of coal. That is but one example.

In Switzerland where everything is grinding to a halt, where industry is ruined because it can no longer produce at prices attractive to world markets, I was told that if the daily working hours were to be increased to ten, with reasonable pay, the workers would find employment for the whole week instead of for the three days during which the factories are now running at a loss merely to stay in existence. Moreover, the workmen themselves would gladly work longer if they dared, but they cannot do so lest they contravene their union’s program. Such is the situation.

This sad state of affairs can, it is true, be blamed partly on the unpredictable fluctuations in the value of money. These are characteristic problems which, it appears to me, not even the experts can satisfactorily explain.

But below the surface of these obvious factors there are, quite plainly, greater internal ones. It is an undeniable fact that people cannot live without working, and there has been too little work for too long. It will be asked: “What is the purpose of work if there is no market for the products?” And markets are indeed not there. But neither can markets be created without work. If no work is done, if markets are not created where they should exist, then no purchasing power will be developed, and everyone must suffer in consequence. The universal disease is, in fact, lack of work. Even honest work cannot thrive, however, except where there are peace and confidence: confidence in one’s self, confidence in others, and confidence in the future.

Here we strike at the heart of the matter. How then can this confidence in peace be inspired? Can it proceed from politicians and diplomats? I have already expressed my opinion of them. They can, perhaps, do something, but I am not particularly convinced of that, nor of the ability of politicians of the individual countries to achieve anything in this situation. In my opinion, the only avenue to salvation lies in cooperation between all nations on a basis of honest endeavor.

I believe that the only road to this goal lies through the League of Nations. If this fails to introduce a new era, then I see no salvation, at any rate at present. But are we right in placing so much faith in the League of Nations? What has it done so far to promote peace and confidence? In asking this question we must remember that the League is still a young plant that can easily be damaged and prevented from growing by the frost of doubt. We should bear in mind that the League can attain full powers only when it embraces all nations, including the big ones still outside7. But even in its short lifetime, it can claim credit for actions which point to a brighter future. It has already in its short active life settled many controversial questions which would otherwise have led, if not to war, at least to serious disturbances.

One example was the Åland controversy between Sweden and Finland. Though there were some who were dissatisfied with the solution8, they nevertheless accepted it, thus preventing further trouble.

A serious frontier dispute arose between Yugoslavia and Albania. Serbian troops had already crossed the border. The League of Nations intervened, settled the question, and both parties accepted the solution9 without further bloodshed.

Mention can also be made of the Silesian question which threatened serious trouble between Germany and Poland. This too has been settled – very badly according to some, while others maintain that any other solution would have been impossible in view of previous agreements reached in the Treaty of Versailles10. But the fact is that the settlement has been sanctioned by both parties and that it has not led to any further trouble.

Another example is that of Poland and Lithuania. It is true that the League of Nations did not in this case reach any settlement, the problem having proved too difficult because of various reasons which I am not going to delve into here. The fact is, however, that the act of investigation by the League of Nations in itself prevented the two parties from taking up arms11.

It may be claimed that these were controversies between small nations, but what if real issues arose between greater powers – would they yield to the arbitration of the League of Nations? Well, I point to the Silesian question again. Germany is no small nation, and it is moreover a fact that the victorious great powers which set out to settle the question were unable to reach agreement; so the matter was referred to the League of Nations. Recently, however, we have had an even better example of great powers submitting to the judgment of the League of Nations in an issue between Great Britain and France.

In 1921 the French government issued a decree declaring that everyone living in Tunisia and Morocco was compelled to do national service. Thus British subjects living in the French protectorates were liable to conscription in the French army. The British government objected strongly, while the French maintained that this was an internal problem. Neither would give in and the controversy became serious. Nine years ago such a question could only have ended in a war or at best in an expensive diplomatic conference. At that time there was no world organization which could have dealt with such a question. Now, however, it was referred to the League of Nations, and the tension was immediately released12.

The mere fact that the League of Nations has set up the Permanent Court of International Justice13 constitutes a great and important step toward the more peaceful ordering of the world, a step in the direction of creating confidence among nations.

If any doubt still exists about the position now occupied by the League of Nations in the minds of people, reference can be made to the last election in Great Britain. Of the 1,386 candidates standing, only three dared to face their electors with a declaration that they were opponents of the League of Nations. Two or three more made no mention of the subject, but all the rest expressed their faith in the League.

In my opinion, however, the greatest and most important achievement of the League so far, and one which presages a really new and better future for Europe, is the measure initiated at the last Assembly in Geneva, that of arranging an international loan to Austria14 to give her a chance of surviving the threat of economic ruin. This action raises hope for yet more; it is the prelude to a new and promising trend in the economic politics of Europe.

It is my conviction that the German problem, the intricate differences between Germany and her opponents, cannot and will not be solved until it too has been laid before the League of Nations15.

In addition, the difficult question of total or partial disarmament was first broached at the last meeting in Geneva. Here, as well as in most other fields of the League’s activity, there is one name which stands out, namely that of Lord Robert Cecil16. Again we must keep in mind, particularly in the matter of partial disarmament, the serious difficulties arising from the fact that there are important military powers which are not yet members of the League.

But more important by far than any partial disarmament of armies and fleets, is the “disarmament” of the people from within, the generation, in fact, of sympathy in the souls of men. Here too, in the great and important work that has been carried on, the League of Nations has taken an active part.

I must, however, first mention the gigantic task performed by the Americans under the remarkable leadership of Hoover17. It was begun during the war with the Belgian Relief, when many thousands of Belgians, children and adults, were supported. After the war, it was extended to Central Europe, where hundreds of thousands of children were given new hope by the invaluable aid from the Americans, and finally, but not least, to Russia. When the whole story of this work is written, it will take pride of place as a glorious page in the annals of mankind, and its charity will shine like a brilliant star in a long and dark night. At the same time, the Americans have, through other organizations such as the American Red Cross and the Near East Relief, achieved the unbelievable in the Balkans, in Asia Minor, and now, finally, in Greece. Many European organizations must also not be forgotten. In particular, divisions of the Red Cross in different countries, among them our own, have contributed much during and after the war.

The League of Nations sponsored activities of this nature soon after its formation. Its first task was the repatriation of the many thousands of prisoners of war still scattered round the world two years after the war, mostly in Siberia and Eastern and Central Europe. I do not intend to dwell on this theme since it has already been mentioned at the meeting in the Nobel Institute. I shall say only that, as a result of this effort, nearly 450,000 prisoners were sent back to their homes and, in many instances, to productive work.

Immediately after this, the League took up the fight against epidemics which were then threatening to spread from the East, and worked to control disease in Poland, along the Russian border, and in Russia itself. The League has, through its excellent Commission on Epidemics18, worked effectively to prevent the spread of epidemics and has saved thousands from destitution and annihilation.

Efforts are now being made, through a special organization sponsored by the League of Nations19, to provide subsistence aid for destitute Russian refugees, more than a million of whom are scattered all over Europe.

Mention must also be made of the work now in progress in support of famine-stricken refugees in Asia Minor and Greece20. It is true that it has still barely begun, but this work too can be of the greatest importance. Under the present conditions in these areas, there is a threat of disorganization and despair worse than anywhere else in Europe. If this danger can be averted or at least reduced, if this malignant growth can to some extent be eradicated, then there will be one such cancer the less in the European community, one risk the less of unrest, of disturbance, of dissolution of states in the future.

Having already emphasized the significance of this type of work, I must do so once more. The relief in thousands of homes in seeing the return of their menfolk, the help received by them in their distress; the gratitude this inspires, the confidence in people and in the future, the prospect of sounder working conditions – all this is, I believe, of greater importance for the cause of peace than many ambitious political moves that now seldom reach far beyond a limited circle of politicians and diplomats.

Finally, a few words about the assistance to Russia21. In this the League of Nations did not participate, a fact which I deeply regret because I cannot but believe that had the League, with its great authority, lent its support while there was still time, the situation in Russia would have been saved, and conditions in both Russia and Europe would now be totally different and much better.

I shall not go into greater detail on the work that has been done. I wish only to emphasize that the difficulty certainly did not lie in finding the food or transporting it to those who were starving. No, there was more than enough grain in the world at that time, and adequate distribution facilities were available. The problem lay in obtaining funds, an obstacle which has always bedeviled such attempts to supply aid – not least so at this moment.

European governments were unwilling to sanction the loan of ten million pounds sterling which appeared indispensable if the starving millions of Russia were to be saved and the famine prevented from turning into a tragedy, not only for Russia, but for all Europe. The only alternative, therefore, was to rely on private contributions and to institute an appeal for charity to individuals all over the world.

The result exceeded every expectation. Donations poured in from all countries, and not least from our own. In spite of the existence of people here at home who thought it right to oppose the collection, the contribution of our little country was still so great, thanks to the Norwegian Parliament, the Norwegian government, and the excellent work of the Famine Committee, that had the big countries contributed in proportion, the famine in Russia would now be a thing of the past.

One notable exception outside Europe must be mentioned. Once again, the American people contributed more than any other, first through the Hoover organization and then through the government itself, which donated twenty million dollars to the fight against famine on the condition that the Russian government would provide ten million for the purchase of seed. Altogether, America has certainly contributed fifty to sixty million dollars to the struggle against the Russian famine, and has thus saved the lives of countless millions.

But why were there some who did not want to help? Ask them! In all probability their motives were political. They epitomize sterile self-importance and the lack of will to understand people who think differently, characteristics which now constitute the greatest danger in Europe. They call us romantics, weak, stupid, sentimental idealists, perhaps because we have some faith in the good which exists even in our opponents and because we believe that kindness achieves more than cruelty. It may be that we are simpleminded, but I do not think that we are dangerous. Those, however, who stagnate behind their political programs, offering nothing else to suffering mankind, to starving, dying millions – they are the scourge of Europe.

Russia is not alone in being threatened by a new and terrible famine. The situation in Europe also looks black enough. No one knows yet where it will end. The destitution is so great, so nearly insurmountable, the conditions so desperate, even in the rich fertile area of Russia, not to mention other countries, that in spite of widespread private generosity, what can be provided constitutes only a drop in the ocean.

Everyone must join in this work. We must take up the fiery cross and light the beacons so that they shine from every mountain. We must raise our banner in every country and forge the links of brotherhood around the world. The governments too must stand shoulder to shoulder, not in a battle line, but in a sincere effort to achieve the new era.

The festival of Christmas is approaching when the message to mankind is: Peace on earth.

Never has suffering and bewildered mankind awaited the Prince of Peace with greater longing, the Prince of Charity who holds aloft a white banner bearing the one word inscribed in golden letters: “Work”.

All of us can become workers in his army on its triumphant march across the earth to raise a new spirit in a new generation – to bring men love of their fellowmen and an honest desire for peace – to bring back the will to work and the joy of work – to bring faith in the dawn of a new day.

* The laureate delivered this Nobel lecture in the Auditorium of the University of Oslo. For this translation the text used is that published in Norwegian in Les Prix Nobel en 1921-1922. The lecture was not given a title; the one used here is taken from the third paragraph of the speech.

1. The Treaty of Westphalia (1648) ended the Thirty Years War (1618-1648).

2. The Congress of Vienna attempted (1814-1815) to settle the political affairs of Europe after the first abdication of Napoleon I; the Holy Alliance, formed in 1815 primarily to maintain the status quo in Europe, lasted until 1848.

3. Count Axel Gustavsson Oxenstjerna (1583-1654), chancellor of Sweden (1612- 1654), prominent figure in Thirty Years War.

4. The Lausanne Conference (1922-1923) resulted in a new treaty of peace between the Allies and Turkey.

5. Jacob S. Worm-Müller (Norwegian historian and politician, 1884-1963), Christiania og krisen efter Napoleonskrigene (Oslo: Grøndahl and Sons, 1922).

7. At the time of this lecture: Germany and Russia, which joined later, and the United States, which never joined.

8. In 1921 the League settled the dispute over the Åland Islands by awarding them to Finland, with autonomous status and an agreement against militarization.

9. Under pressure by the League, the Conference of Ambassadors on November 9, 1921, confirmed the frontiers of 1913 for Albania, also making some concessions to Yugoslavia.

10. By the terms of the Versailles Treaty, a plebescite to determine the frontier in Upper Silesia was held on March 20, 1921; disputes followed, and after study by a committee, the Council of the League made recommendations on October 12, 1921, and named a negotiator; a convention of settlement was signed at Geneva on May 15, 1922.

11. The city of Vilna was assigned to Lithuania by the Paris Peace Conference in 1919, but in the following year was occupied by Poland and annexed in 1922. Bad relations continued from this time, when the laureate was speaking, until 1927-1931 when, over a period of four years, agreements were reached on several issues.

12. The League submitted the dispute to the Permanent Court of International Justice which, in February, 1923 (two months after the laureate’s lecture), found that this question was not a purely internal affair, whereupon the two governments made an amicable agreement.

13. The Permanent Court of International Justice (1921-1945), provided judgments on international disputes voluntarily submitted to it; popularly called the World Court, it was supplanted by the International Court of Justice.

15. Germany, not a member of the League at this time, was admitted in September,1926.

16. Edgar Algemon Robert Cecil (1864-1958), recipient of the Nobel Peace Prize for 1937.

17. Herbert Clark Hoover (1874-1964), president of the United States (1929-1933); director of food administration and war relief bureaus during and after World War I.

19. The High Commission for Refugees was established by the League on June 27, 1921, with the laureate appointed as High Commissioner.

21. On August 15, 1921, an international conference of representatives of certain governments and of delegates from forty-eight Red Cross and charitable organizations had appointed Nansen to direct the relief effort in famine-stricken Russia.

The Nobel Foundation's copyright has expired.Fridtjof Nansen – Documentary

Fridtjof Nansen – Nobel-foredrag

English

Norwegian

Nobel-foredrag hollt i Kristiania den 19de december 1922

Paa Roms Kapitol er der et stykke marmor, som synes mig i sin enkle pathos aa være et av de skjønneste. Det er den »Døende Galler». Han ligger saaret til døden paa slagmarken. Dette spenstige legeme, herdet i arbeid og kamp, nu slappet mot undergangen. Det senkede hode med det strie haar, den bøide, sterke nakke, den grove kraftige arbeidshaand, som netop svang sverdet, nu støttet mot marken for med en siste anstrengelse aa holde det synkende legeme oppe.

Han blev drevet til kamp for fremmede guder, som han ikke kjente, fjernt fra eget land. Saa møtte han sin skjebne. Nu ligger han der og forblør i taushet. Kamptumlen runt ham naar ikke lenger hans øre, det slørede blikk er vent innad; kanskje i et siste klarsyn ser han barndomshjemmet, der livet var enkelt og lykkelig, hjembygden kranset av Galliens skog.

Se, slik ser jeg den lidende menneskehet, slik ser jeg Europas lidende folk forblø paa slagmarkene efter de kampe, som for en stor del ikke var deres egne.

Det var maktbegjæret, imperialismen, militarismen, som raste sin berserkgang over jorden. – Markenes gyldne grøde blev trampet ned unner jernføtter – jorden ligger ødet runt om, – samfunnene knaker i sine sammenføininger. – Men folkene bøier hodene i stum haabløshet. Det gnelrende kamprop larmer enda runt dem, men de hører dem knapt nok lenger. Blikket søker tilbake mot de enkle, oprindelige livsverdier, som ligger stengt bak det Eden, som er tapt. Verdenssjelen er syk til døden, motet er brutt, idealene er bleknet, livsviljen ménskutt; det fjerne blaaner sløret bort bak ødeleggelsenes brannskyer – troen paa morgenrøden er ikke mer.

Hvor skal helseboten søkes? – Hos politikerne? Ja, de mener det vel godt nok, mange av dem ialfall; men se, det er ikke mer politikk verden nu trenger, ikke nye politiske programmer – verden har bare hat saa alt for mange av dem. Til slutt er det nu heller ikke stort annet enn kamp for makt politikernes kampe gaar ut paa.

Kanskje hos diplomatene? De mener det kanskje ogsaa bra nok, men de er nu engang en steril rase, og de har bragt menneskeheten mere ondt enn godt ned gjennem tidene. Vi maa minnes opgjørene efter de store krige, Westfalerfreden, Wienerkongressen med Den Hellige Alliance og hvad de allesammen heter. Har en eneste en av disse diplomatiske kongresser bragt verden stort fremover? En maa tenke paa Oxenstjernas berømte ord til sin son, da han klaget over forhandlingene i Westfalen. »Du skulde bare vite, min son, med hvor liten visdom verden blir styrt.»

Nei, til de styrende ser vi ikke lenger med haab om redning. Vi har oplevet den ene diplomatiske og politiske kongress efter den annan i den senere tid; – har en eneste en av dem bragt oss løsningen, helseboten vesentlig nærmere? Der sitter netop en i Lausanne. La oss haabe, at den maa bringe oss den saa haardt trengte fred i Østerlandene, saa er det da ialfall et vanskelig spørsmaal mindre.

Men selve hovedondet, selve sotten? – Det hviskes om, at Frankrike ønsker ikke no’e endelig opgjør med Tyskland; ønsker ikke, at Tyskland skal endelig betale sin skadeserstatning; ti da mister de paaskuddet til aa holde den venstre Rhinbredd besatt, og de kan ikke lenger forstyrre den tyske industri med trusler mot Ruhrdistriktet. Det er selvsagt ondskapsfull bakvaskelse, men bare det, at slikt kan hviskes!

Det hviskes ogsaa om, at heller ikke Tysklands industriherrer ønsker noen endelig ordning med Frankrike, de ønsker den slingrende, usikre kurs fortsatt; for da faller marken stadig, og den tyske industri kan drive videre. Men kom ordningen, da vilde marken stabiliseres eller endog stige og den tyske industri var ødelagt, den kunde ikke lenger klare konkurransen.

Sant, eller ikke, – bare at slikt kan sis, det gir ialfall et billede av hvordan hele det europeiske samfunn og dets liv har vært og er en ball i hendene paa samvittighetsløse spekulanter, politiske spekulanter, pengespekulanter – klodrianer for en stor del kanskje, undermaalsmenn, som ikke forstaar hvor det bærer hen; men likevel spekulanter, som spiller hasard med det europeiske samfunns dyreste interesser.

Og for hvad? Bare for makt. Denne ulykkelige kamp for makt, denne forferdelige nedtrampen av alt og alle for makt, denne ødeleggende kamp mellem samfunnsklasser, mellem folk for makt!

Har en staat ansikt til ansikt med hungersnøden, selve sultedøden, saa vilde en vel faat øinene op for ulykken i dens fulle rekkevidde. Har en sett de store bønfallende barnøine i de uttærte barneansikter stirre haabløst inn i det sluknende dagslys, sett da utpinte mødres øine, mens de i stum redsel trykket det døende barn til de tomme bryster, sett disse gjenferd av menn ligge utpint i kullen paa hyttegulvene og vente bare paa en ting, den barmhjertige død, – da maatte en vel forstaa, hvor dette bærer hen, forstaa litt av hvad det virkelig gjelder. – Der var det ikke kampen for makt, det var en eneste, forferdelig anklage mot de mange, som enda ikke vil se – en eneste, stor bøn om en draape barmhjertighet for aa gi dem livsmulighet.

Ja, har en først, sett all nøden paa nært holl runt om i vaart vanstyrte Europa, gjennemlevet litt av de uendelige lidelser – da maa en vel føle, at det er ikke lenger programmer, ikke mere papir, ikke lenger ord, verden trenger. Det er handling, iherdig og møisommelig arbeid, søm maa begynne nedenfra for aa bygge verden op paany.

Menneskehetens historie gaar i bølger. Vi har hat bølgedaler før i Europa. Vi hadde en lignende bølgedal for hundre aar siden, efter Napoleonskrigene. Den som har lest Worm-Müllers ypperlige verk om tilstannene her i Norge paa den tid, han maa slaas av de merkelige likheter mellem nedgangen dengang og nu, paa mange imater. Det kan være en trøst aa vite, at dengang gik det over, og det gik opover igjen; men det tok en sørgelig lang tid, tredve til førti aar.

Denne gang er bølgedalen enda dypere, saa vitt jeg skjønner, for den har større omfang, den omfatter langt større deler av Europa; og dertil kommer, at forholdene nu er mer kompliserte, mer sammensatte. Vistnok var det ogsaa den gang industri, men likevel levet folkene i langt større utstrekning av sit akerbruk. Nu er industrien kommet mer til makten, og den har langt vanskeligere for aa klare sig op igjen efter en nedgangstid enn landbruket har. Noen gode aar bringer landbruket paa fote, men mange aar maa til for aa skaffe industrien nye markeder. Likefullt kan vi vel kanskje haabe paa, at det skal gaa fortere med gjenreisningen denne gang: for allting gaar nu engang hurtigere i vaar tid, med vaare samferdselsmidler og hele det store apparat av hjelpemidler vi nu har. Men det er enda lite aa merke til fremgangen, vi er enda ikke kommet til bunnen av bølgedalen.

Hvad er grunnstemningen i folkene rundt om i Europa? Det er vel for en stor del haabløshet, eller ogsaa mistillit til alt og alle, og saa hat og misundelse; og hatets dragesed saas fremdeles daglig mellem folkene, mellem klassene.

Men paa haabløshet, mistillit, hal og misundelse bygges ingen fremtid.

Den første betingelse er vel furstaaelse – forstaaelse først og fremst av selve sykdommens aarsak og vesen, forstaaelse av strømningene som gaar gjennem tiden, av hvad som arbeider i folkedypet – kort sagt, forstaaelse av hele det tilsynelatende saa forvirrede og forvillede europeiske samfunns psykologi.

En slik forstaaelse er sikkerlig ikke naadd paa én dag. Men den første betingelse for at den kan naas, er den ærlige vilje til aa forstaa; det er et langt skritt paa veien. Ved den stadige utskjellen av anderledes tenkende, som vi daglig er vidne til i avisene, naas saa visst ingen fremskritt. Skjellsord overbeviser ingen, de bare fornedrer och forraaer den som bruker dem. Ved løgn og falske beskylninger naas enda mindre; de faller tilslutt tilbake paa dem, som satte dem ut.

Det bør ogsaa stadig minnes, at der er knapt nok noen strømning eller noen bevegelse i samfunnet, som ikke har sin særlige, rimelige aarsak og berettigelse, det være sig socialisme eller kapitalisme, det være sig fascisme eller endog den forhatte bolsjevisme. Men det er ved den uforstaaende fanatismen for og imot – og kanskje helst imot – at motsetningene tilspisses, og at de opslitende kampe fører til ødeleggelse, der hvor tankebrytning, hvor forstaaelse og forstaaende handlinger kunde vennt alt til verdifullt fremskritt.

Det vilde føre for langt her aa gaa inn paa dette emne; men ordet om at du ser skjeven i din brors øie, men bjelken i dit eget blir du ikke var – det ord har gyldighet til alle tider og ikke minst i vaar.

Men ved mangelen paa forstaaelse, og mest av alt, ved den manglende vilje til aa forstaa, er det den gjæringens usikkerhet er skapt, som truer oss med hel ødeleggelse. Ingen vet hvad som kommer imorgen. Mange lever – ute i verden ialfall – som om hver dag var den siste, og det skaper forfall paa alle kanter. Det glir videre, nedover – nedover.

Men det verste som denne utryggheten, denne spekulation i usikkerheten skaper, det er fremdeles arbeidsskyheten; den blev avlet unner krigen, og den er stadig underholdt siden. Den blev avlet ved jobbingen og spekulationen, som vi alle kjenner, da folk kunde tjene formuer paa kort tid, og mente de kunde leve av det resten av livet, og det aa arbeide, slite var ikke lenger nødvendig. Det skapte arbeidsskyheten, og den varer den dag idag. Der er endnu faa som ærlig og redelig vil sette sig ned til slitsomt arbeid. Det eneste sted hvor jeg har møtt ærlig arbeidsvilje, det er der, hvor sultens dødsengel har hat sin uhyggelige høst.

Jeg maa minnes en dag i en lansby østenfor Volga, hvor der bare var en tredjedel av innbyggerne tilbake; de to tredjedeler var dels flyktet og dels døde av sult. Dyrene var for mesteparten slaktet ned; men likevel var ikke motet helt slukkt, og om enn utsiktene var mørke, saa hadde de ennu tro paa en mulig fremtid. De bad: Gi oss saakorn, saa skal vi nok sørge for aa faa det i jorden. Ja, svarte vi; men hvad vil dere gjøre uten trekkdyr? Det er det samme, sa de, har vi ikke trekkdyr, saa spenner vi oss selv og vore koner og barn for plogen. Der var det ikke nydelsessyken som talte; ikke luksusen, ikke flitterstasen – det var selve livsviljen, som ikke lot sig kue.

Skal det da være nødvendig, at vi alle maa gjennem sultens bitre pine før vi lærer arbeidets virkelige verd?

Jeg kunde nevne forhollene i Tyskland. Det er mig sagt at i Tyskland er det paa grunn av arbeidstidens korthet og arbeidstempoet ikke mulig aa drive frem de kull, som er nødvendige for Tysklands eget behov, og at de maa faa kull fra England, – jeg tror det var nevnt 1 million ton maanedlig – og betale dem med utenlansk valuta. Men hvis arbeidstiden i Tyskland kunde forlenges til ti timer daglig, kunde Tyskland selv produsere sine kull. Det gir et billede.

I Schweiz, hvor alt ligger nede, hvor industrien er ødelagt fordi den ikke lenger kan produsere til de priser som er nødvendige for verdensmarkedet, der er det sagt mig at hvis arbeidstiden kunde forlænges til 10 timer, med en rimelig lønning, vilde arbeiderne kunne faa arbeid hele uken gjennem, istedenfor nu kanskje 3 dager som fabrikkene gaar med tap bare for aa holde dem i live. Og arbeiderne vilde gladelig ta det; men de tor ikke, for det var aa opgi sitt program. Det er tilstannen.

Disse bedrøvelige tilstanne kan vel for noen del skyldes valutaen, pengenes uberegnelige svingninger. Se det er egne problemer, som det synes mig selv ikke de sakkyndige kan gi os tilfredsstillende oplysning om.

Men dypere enn disse umiddelbare aapenlyse aarsaker ligger selvsagt større indre aarsaker. Saken er jo den at menneskene kan nu engang ikke leve uten at det blir arbeidet, og i lang tid har det vært arbeidet for lite. Man vil svare mig: hvad nytter det aa arbeide, hvis der ikke er marked for produktene? Og markedene mangler. Men markeder blir nu heller ikke skapt uten arbeid. Hvis det ikke arbeides der hvor markedene skulde være, blir der ikke nogen kjøpeevne, og alle maa lide for det. Sotten hele verden over er faktisk mangel paa arbeid. Et jevnt ærlig arbeid kan imidlertid ikke trives, uten hvor der er fred og tillit. Tillit til sig selv, tillit til andre, og tillit til fremtiden.

Her er vi ved selve kjernepunktet. Hvordan kan denne fredens tillit skapes? Skulde det være gjennem politikkerne og diplomatene? Jeg har alt uttalt mig om dem. De kan vel gjøre no’e kan henne; men jeg har ikke synderlig tro paa det, eller paa at de enkelte lands politikkere kan gjøre no’e større her. Jeg ser den eneste redning i et samarbeid av alle nationer i ærlig vilje.

For aa opnaa det mener jeg veien gaar gjennem Nationenes Forbunn. Kan ikke ad den vei den nye tid bringes inn, ja da ser ikke jeg noen redning, i alle fall ikke foreløbig.

Men ha vi rett til aa stille saa stort et haab til Nationenes Forbunn? Hvad har det gjort hittil for aa fremme fred og tillit? Naar en stiller dette spørsmaal, maa en vell huske paa, at det enda er et ungt tre som tvilens nattefrost lett kan skade og stanse i veksten. Vi maa erindre at forbunnet først kan komme til full kraft naar det omspenner alle, ogsaa de store nationer som fremdeles er utenfor. Men likevel kan det alt i sin korte levetid opvise handlinger, som peker mot en lysere fremtid. Det kan nevnes blant annet at det alt i sin korte levetid har bilagt flere stridsspørsmaal som ellers vilde ha ført, om kanskje ikke alle til krig, saa i hvert fall til alvorlige uroligheter.

Jeg kan nevne Ålands-spørsmaalet mellem Sverige og Finland. Det var dem som ikke var tilfreds med løsningen, men de tok den i hvert fall og akkviescerte ved den; den forte ikke til mere ufred.

Mellem Jugoslavien og Albanien var der et alvorlig stridsspørsmaal om grensene. De serbiske tropper hadde alt overskredet grensen, Nationenes Forbunn skred inn, avgjorde spørsmaalet, og begge parter mottok løsningen uten videre strid.

Nevnes kan ogsaa det schlesiske spørsmaal, som truet med alvorlige uroligheter mellem Tyskland og Polen. Det blev avgjort – meget slett sa noen, andre sa det kunde ikke afgjøres annerledes som nu engang de tidligere overenskomster i Versailles-freden var avfattet – men faktum er at begge parter har vedtatt avgjørelsen, og det har ikke ført til videre ufred.

Jeg kunde ogsaa nevne Polen og Litauen. Vistnok traff ikke Nationenes Forbunn der noen avgjørelse, spørsmaalet viste sig for vanskelig av forskjellige grunner, som jeg ikke her skal gaa inn paa; men faktum er likevel at selve den kjensgjerning, at Nationenes Forbunn hadde spørsmaalet unner behandling, hindret de to parter fra aa gripe til vaaben mot hverandre.

Hvis noen vil innvenne, at dette er stridigheter mellem smaa nationer, uten om det kommer til virkelige stridigheter mellem de store – vil de da bøie sig for Nationenes Forbunns avgjørelse? Nu, jeg kunde jo nevne dette schlesiske sporsmaal. Tyskland er ikke noen liten nation, og desuten er det et faktum at de seirende stormakter, som skulde avgjore spørsmaalet, heller ikke kunde bli enig om det, og saa blev det henvist til Nationenes Forbunn. Men nylig har vi hat et enda bedre eksempel paa at stormaktene bøier sig for Nationenes Forbunn, og det var et stridsspørsmaal mellem Storbritannien og Frankrike.

I 1921 utstedte den franske regjering en forordning, hvorved alle som bor i Tunis og Marokko blev tvunget til verneplikt. Paa den vis vilde ogsaa britiske undersaatter, bosatt i de franske protektorater, bli tvunget til aa gjøre fransk militærtjeneste. Den britiske regjering protesterte kraftig: den franske hevdet at det var et indre spørsmaal. Ingen vilde gi sig, og striden blev alvorlig. For 9 aar siden vilde et slikt spørsmaal ikke ha ført til noe annet alternativ enn enten krig eller en kostbar diplomatisk konferanse. Der var ingen verdens-organisasjon dengang som kunde ta et slikt sporsmaal unner behandling. Nu blev det henvist til Nationenes Forbunn, og spenningen ga sig straks.

Bare det at Nationenes Forbunn har oprettet den permanente internationale domstol er jo et stort og betydningsfullt skritt fremover mot en fredeligere ordning i verden, ett skritt fremover til aa oprette tillit mellem folkene. Ved sitt internationale arbeidsbyraa har Nationenes Forbunn innlagt sig stor fortjeneste paa et annet men ogsaa viktig omraade.

Hvis noen skulde være i tvivl om den stilling, som Nationenes Forbunn nu inntar i folkenes omdømme runt om, saa kan det pekes paa det siste valg i Storbritannien. Av 1386 kandidater, som stillet sig til det britiske valg, var det bare 3 som vaaget aa møte sine velgere med den erklæring, at de var motstandere av Nationenes Forbunn. Det var 2 eller 3 andre som ikke nevnte det; men hele resten uttalte sin tro paa Nationenes Forbunn.

Men det største og det viktigste, som Forbunnet efter min opfatning ennu har gjort, og som innvarsler en virkelig ny bedre tid i Europa, det er det skritt som blev innledet paa den siste forsamling i Genf for aa formidle et internationalt laan til Østerrike, hvorved dette land er gitt haab om redning fra den økonomiske ruin som truet det. Og det gir haab om mere dette tiltak. Det gir haab om en ny lovende retning i Europas økonomiske politikk.

Min tro er nu den, at ogsaa det tyske problem, den tyske floke mellem Tyskland og dets motstandere, ikke kan loses og ikke vil bli lost, før ogsaa den blir lagt inn unner Nationenes Forbunn.

Ogsaa paa den vanskelige avrustnings eller nedrustnings omraade er innledende skritt tatt paa den siste forsamling i Genf. Og her, som paa de fleste andre omraader av Forbunnets virksomhet er det et navn som lyser fremfor andre, og det er Lord Robert Cecil. – Men særlig naar det gjelder dette spørsmaal om nedrustning, maa de store vanskeligheter erindres, som reises bare ved den kjensgjerning at det er viktige militærmakter, som ennu ikke er medlemmer av Forbunnet.

Men enda ulike viktigere enn all nedrustning av arméer og flaater er avrustningen av folkene innenfra, aa skape samfølelse i folkenes sinn. Og her er et stort og viktig arbeid utført, og Nationenes Forbunn har tatt virksom del.

Men først og fremst maa jeg nevne det kjempearbeid, som amerikanerne har utfort under Hoovers merkelige ledelse. Det begynte unner krigen, med »Belgian Relief», med mangfoldige tusener av mennesker i Belgien, barn og andre, som blev underhollt. Saa gikk det videre til Central-Europa efter krigen, da hundretusener av barn fik nytt livshaab ved amerikanernes storslaatte hjelp, og sisst og ikke minst i Rusland. Naar engang det arbeids hele saga skrives, vil det staa som et enestaaende lysende blad i menneskehetens og menneskekjærlighetens historie, en forsonende stjerne i en lang og mørk nat. Samtidig har amerikanerne gjennem andre organisasjoner, det amerikanske Røde Kors og »Near East Relief», utrettet det utrolige paa Balkan, i Lilleasien, liksom nu sisst i Grekenland. Mange europeiske organisationer maa heller ikke glemmes, særlig avdelinger av Det Røde Kors i forskjellige land, ogsaa i vaart, har ydet meget unner og efter krigen.

Snart efter sin dannelse tok Nationenes Forbunn op virksomheter av denne art. Det første skritt var arbeidet for aa sende hjem de mange tusener av krigsfanger, som ennu to aar efter krigen var sprett runt i verden, mest i Sibirien og i øst- og Central-Europa. Jeg skei ikke her gaa inn paa dette, det blev omtalt allerede i møtet i Nobelinstitutet. Jeg skal bare nevne at bortimot 450,000 fanger ved det arbeid blev gitt tilbake til sine hjem og tildels til produktivt arbeid.

Saa tok Nationenes Forbunn ogsaa straks op bekjempelse av epidemier, som var en farlig trusel fra øst, og det arbeidet mot epidemier i Polen, langs grensen av Rusland og i Rusland selv, og det har gjennem sin ypperlige epidemi-kommisjon gjort et stort arbeid for aa forebygge farsotter og har reddet tusener fra nød og unnergang.

Gjennem en særlig organisasjon under Nationenes Forbunn arbeides det for aa skaffe levelige kaar for de mange nødlidende russiske flyktninger utenfor Rusland, hvorav det er over en million sprett rundt om i Europa.

Nevnes maa ogsaa det nu paagaaende arbeid med hjelp til de nødlidende flyktninger i Lilleasien og Grekenland. Det er jo i sin begynnelse ennu, men ogsaa dette arbeid kan ha en stor betydning. Som tilstannen er nu, truer det med opløsning og fortvilelse av enda verre art enn paa noe annet sted i Europa. Hvis det kan lindres, hvis det kan minskes, hvis kreftbylden i noen grad kan leges, saa er der en kreftbyld mindre paa det europeiske samfunn, en fare mindre for uro, for ufred, for opløsende krefter i fremtiden.

Jeg nevnte det sisst, jeg maa nevne det igjen: Den store betydning som det har, arbeid av denne art. Hjelp til de tusener av hjem som faar sine menn tilbake, som blir hjulpet i sin nød. Den takknemlighet det skaper, den tro, den tillit til menneskene og til fremtiden, den mulighet for sunnere arbeidskaar, – det har, mener jeg, en større betydning for freden enn mangen storpolitisk akt, som nu sjelden naar stort lengere ned enn til en skiftende kreds av politikkere og diplomater.

Til slutt noen ord om hjelpen til Rusland. Der var Nationenes Forbunn ikke med, og jeg beklager det dybt; for jeg kan ikke tro annet enn at hadde Forbunnet traadt støttende til med sin store autoritet, mens det ennu var tid, vilde stillingen i Rusland ha vært reddet, og stillingen i Rusland og Europa vilde nu ha vært helt annerledes og bedre.

Jeg skal ikke her gaa nærmere inn paa det arbeid som er gjort. Jeg vil bare fremholde, at vanskeligheten var sandelig ikke aa finne maten eller aa faa den skaffet frem til dem som sultet. Aa nei, der var korn mer enn nokk i verden dengang, som det er nu i dette øieblikk, der var ogsaa transport nokk. Men vanskeligheten var alene aa skaffe pengene, da som alltid i vaart hjelpearbeid siden, – ikke minst i dette øieblikk.

Da regjeringerne i Europa ikke vilde gi det laan paa ti millioner punn sterling, som jeg mente var uundgaaelig nødvendig for aa redde Ruslands sultende millioner, for aa hindre at hungersnøden skulde bli en stor ulykke ikke bare for Rusland, men for hele Europa, saa var det ikke annet for enn aa gjøre hvad gjores kunde ad privat vei, og rette en appell til den private godgjørenhet verden over.

Og svaret var over al forventning storartet. Det strømmet inn fra alle land, ikke minst fra vaart eget. Uagtet det var dem her hjemme, som fant det riktig aa motarbeide innsamlingen, blev det likevel, takket være det norske Storting og den norske regjering, og takket være hungersnødskomiteens ypperlige arbeid, gitt saa meget fra vaart lille land, at hadde de andre store land gitt noe saa nær i forhold, da hadde den russiske hungersnød nu vært beseiret.

Jeg maa nevne en unntagelse, men det er utenfor Europa. Det er igjen det amerikanske folk, som ydet mere enn no’e annet. Først gjennem Hoover’s organisasjon og saa regjeringen selv, som ga tyve millioner dollars til aa bekjempe hungersnøden, på betingelse av at den russiske regjering ga ti millioner til innkjøp av saakorn. Alt ialt har visst Amerika gitt femti til seksti millioner dollars til bekjempelsen av den russiske hungersnød, og de har reddet millioner paa millioner av liv.

Men hvorfor var det dem som ikke vilde hjelpe? Ja, spor dem selv. Nærmest var det vel politikk. De er representanter for den golde selvgodhets manglende vilje til aa forstaa annerledes tenkende, som nu er Europas største fare. De kaller oss sværmere, godfjottinger, sentimentale idealister, fordi vi kanskje har litt tro paa det gode ogsaa hos motstandere, og som har tro paa at godhet fører lengere enn haardhet. La saa være at vi er godtroende, saa farlige trør jeg nu i hvert fall ikke vi er. Men de som forbener sig bak sine politiske programmer og holder dem frem til den lidende menneskehet, til sultende, døende millioner – de holder paa aa legge Europa øde.

Og det er ikke bare i Rusland det truer med en ny forferdelig hungersnød. I Europa ellers ser det ogsaa mørkt nokk ut. Ingen vet enda hvor det bærer hen. Nøden er saa stor, saa næsten uoverkommelig, tilstannen saa fortvilende baade i Ruslands rike fruktbare strøk og i andre land, at tross all privat offervilje fra de mange, blir det som kan skaffes bare som en draape i det store hav.

Alle maa være med i arbeidet. Vi maa la budstikken gaa, vi maa tenne vardene saa det lyser fra alle fjell. Vi maa reise vaare faner i alle land, vi maa danne en broderkjede jorden runt – regjeringene maa ogsaa med – skulder til skulder, ikke til kamp, men til ærlig arbeid for den nye tid.

Julens hvite høitid stunder til, da budskapet til menneskene lyder: Fred paa jorden.

Aldrig har den lidende forvillede menneskehet ventet med storre lengsel paa fredsfyrsten, paa ham som kjenner sitt kall, menneskekjærlighetens fyrste som løfter det hvite banner, med det ene ord lysende i gylden skrift; Arbeid.

Hver og en av oss kan bli arbeider i hans fylking paa dens seiersgang over jorden for aa reise den nye slekt – for a bringe næstekjærlighet og ærlig fredsvilje – for aa bringe arbeidsvilje og arbeidsglede tilbake til menneskene – bringe troen paa morgenrøden.

The Nobel Foundation's copyright has expired.

Fridtjof Nansen – Other resources

Links to other sites

‘Fridtjof Nansen. Man of many facets’. Article by Linn Ryne

On Fridtjof Nansen from Fridtjof Nansen Institute

On Fridtjof Nansen from Norwegian Refugee Council

‘Nansen – a man of action and vision’ from UNHCR

‘Compassion in action’ – a digital exhibition from the Nobel Peace Center

Fridtjof Nansen – Nominations

Fridtjof Nansen: Scientist and humanitarian

Fridtjof Nansen: Scientist and humanitarian

by Asle Sveen*

This article was published on 15 March 2001.

In the summer of 1922, the last of the German and Austria-Hungarian soldiers who had been in Russian captivity after the First World War were shipped home across the Baltic. On the return voyage, the ships carried the last Russian prisoners-of-war from Germany. Altogether, over 400,000 prisoners were exchanged in less than two years. The credit for this was given mainly to the Norwegian Fridtjof Nansen. That autumn he was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize. Nansen did his country great service as a politician and diplomat, but he acquired his international renown primarily as a scientist, polar exploration hero, and the altruistic champion of people in times of distress.

Well off, intelligent and sporty

Fridtjof Nansen was born in Kristiania (as Oslo was then known) in 1861.1 His father was a pious lawyer, and his mother belonged to one of the few aristocratic families in Norway, at the time a poor country.2 The family was relatively well off. Fridtjof was sent to a private school, where he distinguished himself in all subjects from classical languages to mathematics and sports.

In the 1870s, skiing was rapidly gaining in popularity among Kristiania’s upper class. Both Fridtjof’s parents were enthusiastic about the sport, and encouraged their son to participate, which he did, with great success. The picture shows Fridtjof Nansen skiing in Lysaker.

In 1880 he took the university matriculation examination and began to read zoology at the only Norwegian university, in Kristiania. He proved himself to be outstanding in both knowledge and industriousness, so the university sent him to the Arctic on a sealing vessel to take samples of marine life. It was on the four-month expedition in the waters off Greenland that Nansen first acquired his taste for the polar regions. He did such good work that he obtained an attractive research post at Bergen Museum. The old Hanseatic town of Bergen was the only town in Norway with a continental atmosphere. For want of a university, some of its prosperous citizens had instead set up an independent research centre. In Bergen young Nansen came into contact with internationally-minded scientists, including Armauer Hansen, discoverer of the leprosy bacillus. The scientists in Bergen were enthusiastic adherents of Darwin’s new theory of evolution, and Nansen soon became a convinced Darwinist – a fact he kept from his strictly religious father.

Science and adventure

Nansen threw himself into the study of the invertebrate nervous system. One of Darwin’s main points had been that all living organisms were related. Nansen accordingly believed that by studying the relatively simple nervous system of the hagfish, he could arrive at some of the principles underlying the working of the human central nervous system and brain.

Fridtjof Nansen with a microscope at Bergen Museum, 1887.

Nansen enjoyed his work in Bergen, but disliked the snowless west coast winters. In the winter of 1884, he attracted nationwide attention by skiing across the mountains from Bergen to Kristiania to take part in ski jumping and cross-country skiing competitions.

Nansen was aiming for a doctorate in zoology and used a travel grant to visit Germany, Switzerland, and Italy, where he met recognised scholars in his field. But the polar regions were calling, and while working on his doctorate, he was also planning to become the first person to cross Greenland on skis. He was sponsored by a wealthy Danish businessman, and in 1888 he completed the strenuous journey in the company of three Norwegians and two Sami.

This made Nansen a national and international celebrity in one stroke. In Kristiania the Greenland-farers were greeted by bands, artillery salutes, and a cheering crowd of 50,000 people. Norway was the junior partner in the union with Sweden, and people were hungry for national heroes of their own. Nansen received invitations to lecture at The Royal Geographical Society in London and in several other European capitals. A book on the Greenland expedition, published in several languages with Nansen’s own photographs and drawings, placed him on a sound financial footing.

A contributor to Norwegian national pride

He had obtained his doctorate four days before leaving for Greenland, and in the autumn of 1889 he married the singer Eva Sars.3 Among the reasons why he fell for her was that she was a good skier and enjoyed outdoor activities.

Despite his secure position as an internationally recognised scientist and explorer, Nansen could not settle down. He had set himself the target of reaching the North Pole, planning to use a ship which could drift with the ocean currents, crossing the Pole from east to west. His plan won the support of the Norwegian government. Norwegian nationalism was reaching fever pitch, and to obtain a higher profile in the union with Sweden the country needed all the international prestige it could get.

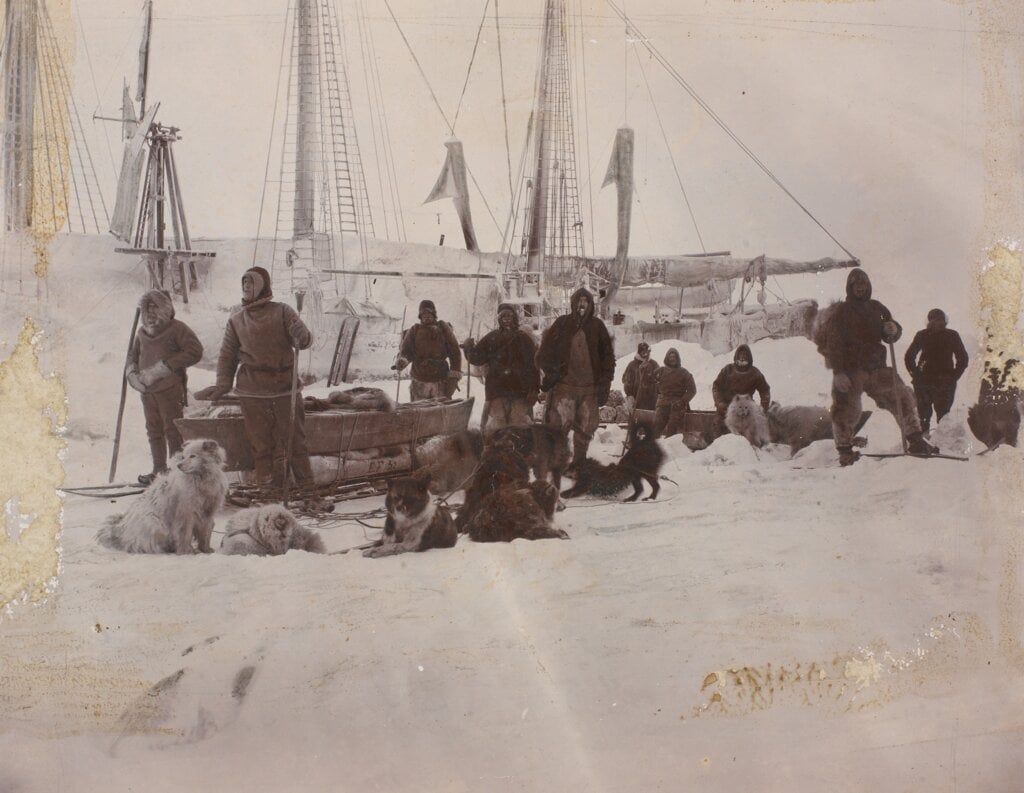

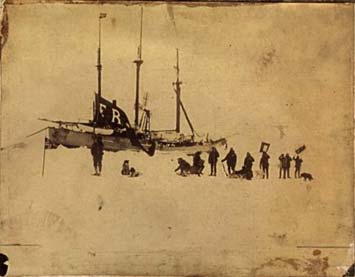

National expansion in the cold. Members of Nansen’s “Fram” expedition to the North Pole celebrate Constitution Day with flags and banners on May 17, 1894.

Nansen had the polar vessel “Fram” built.4 It was designed so as to prevent the ice from pressing it down. In 1893, Nansen allowed the “Fram” to be frozen into the drift ice north of Siberia in the hope that it would drift over or close to the North Pole. However, it soon became evident that the ship was drifting too far south. With one companion, Hjalmar Johansen, Nansen left the “Fram” and the rest of the crew, and set off to ski to the North Pole. They got further north than anyone had been before, but drifting ice and lack of food forced them to turn back and seek the mainland. They survived two winters by shooting walruses and polar bears. By an incredible stroke of luck, they stumbled across a British expedition, headed by Frederick George Jackson, on Frans Josefs Land, which took them back to Norway. The “Fram” also reached home safely with its whole crew intact. Although the North Pole had not been reached, Nansen was celebrated as a polar hero to an even greater extent than before, both nationally and internationally. In Kristiania he was received at the palace by King Oscar, and on the palace balcony accepted the plaudits of the enormous crowd assembled outside.

When “Fram” returned to the Norwegian capital on September 9, 1896, she was met by more than a hundred vessels in the Oslo fjord. A few days later, thousands of people gathered in a popular feast to honor Nansen and his crew.

Diplomat of a new independent nation

During the period of Nansen’s absence, relations between Norway and Sweden had approached a crisis. The two countries were formally equal, but the King was Swedish-born, and Sweden managed the foreign affairs of both countries. More and more people in Norway were inclined to break out of the union with Sweden. Nansen agreed and exploited his international fame to plead Norway’s cause abroad, especially in Britain.

When the break came in 1905, Nansen strongly opposed the most ardent nationalists, who were urging war unless Sweden accepted all of Norway’s demands. He was also in favour of a monarchy, and the Norwegian government sent him to persuade Denmark’s Prince Carl to become King of Norway, taking the old Norwegian royal name of Haakon. As he was married to England’s Princess Maud, this would ensure important foreign policy links to Britain. The new Norway based its foreign policy to a large extent on the protection of the British Royal Navy. Nansen became Norway’s first ambassador to Great Britain, where he became a personal friend of the British Royal Family.

Fridtjof Nansen in uniform when he served as Norwegian Ambassador in London.

In 1907, Nansen tragically lost his wife, which left him a widower with five children. Relations with Eva had been troubled, both because he was away so often on expeditions, lecture tours, or official business, and because he attracted many women.

Nansen’s hopes of being the first to reach both the North and the South Pole were crushed by Robert Peary in 1909 and Roald Amundsen in 1911. He therefore decided to devote more attention to his scientific career. But the outbreak of the World War in 1914 drove him back into politics. Neutral Norway was dependent on imports of cereals and other supplies, and Germany’s unlimited submarine war hit the country very hard. In 1917, Nansen was sent to the United States to seek supplies for Norway. The negotiations were protracted because the United States wanted to pressure Norway into joining the war on the Allied side. While there, Nansen became acquainted with President Wilson’s “Fourteen Points” for peace, and when he returned to Norway he became chairman of the Norwegian League of Nations Association. In that capacity, he attended the Versailles Peace Conference in 1919.

A humanitarian from a small, neutral country

While the peace negotiations were going on at Versailles, the civil war between Reds and Whites was raging in Russia. It resulted in famine and American politicians wanted to exploit food aid as a means of winning concessions from Lenin’s regime. One American claim was for the release of all Americans in Soviet captivity in return for food aid. They sought Nansen’s help as an intermediary in the negotiations with the Bolsheviks. Nansen was not unwilling, but the plan was abandoned when the civil war ended in a victory for the Reds.

Russia was still holding 250,000 prisoners-of-war from the First World War, Germans as well as people of many other nationalities from the dissolved Austria-Hungary. An estimated 200,000 Russians were prisoners on the German side. In the spring of 1920, the League of Nations appointed Nansen as High Commissioner in charge of arrangements for exchanges of prisoners. The appointment came about thanks to the efforts of Philip Noel-Baker, a young British member of the League of Nations leadership. Noel-Baker was eager to boost the League’s reputation after the American Senate had rejected US membership. The League needed to be able to point to concrete results, which Noel-Baker believed Nansen would be able to deliver.

To some extent, the ground had already been prepared. The Red Cross had taken up the cause, and Russia had released the prisoners. The problems were money, and the ships to carry the prisoners home. These became Nansen’s main tasks. Thanks to his popularity in Britain, he was able to persuade the British government to grant loans to finance the exchanges of prisoners. Nansen also got the British to agree to release German ships which had been commandeered since the World War, so they could be used to transport prisoners of war across the Baltic.

950 German prisoners-of-war on board “Cyprus” arrive in Szczecin on July 26, 1921, after having crossed the sea from Riga.

While waiting to be shipped out, the eastern prisoners needed food and clothes. The Communist leaders were suspicious of the Western governments which had supported the Whites in the civil war and refused to negotiate with anyone other than Nansen. From an office in Berlin, known as Nansen Aid,5 Nansen arranged for supplies of food, clothes and medicines for the prisoners on Soviet territory.

While this help was being provided, a period of famine began in the Soviet Union. In the summer of 1921, the author Maxim Gorky appealed for international aid. An American aid organization headed by Herbert Hoover negotiated an agreement with the Russians. They would obtain food aid in return for releasing American prisoners and using their gold reserves to buy grain in the USA.

Lenin saw Nansen and the League of Nations as a possible counterweight to the United States. At the request of Gorky and the League, Nansen went to the Soviet Union, where he was taken to the famine-stricken areas. But his appeal for help was met with scepticism on the part of western governments. The British in particular, now viewed Nansen as Lenin’s naive tool. They were afraid food aid would strengthen the Communist regime. Nansen argued that an economic boycott of the Soviet Union, in addition to increasing the suffering of the starving people, would also be an obstacle to trade between Russia and the rest of Europe and that without such trade, European postwar reconstruction would be impeded.

These views won no support among the western governments, so Nansen was obliged to rely on private charity. The help he was able to provide was therefore modest compared to America’s. To help him with its organization, he had a young Russian-speaking Norwegian, Vidkun Quisling.6 (Ten years after Nansen’s death, Quisling’s name was to become synonymous with traitor when he supported the German occupation of Norway.)

In the summer of 1922, Nansen was able to report to the League of Nations that the repatriation of over 400,000 prisoners of war had been completed. At the same time, he thanked the International Red Cross, which had carried out the bulk of the practical work.

The Red Cross had also made Nansen’s name known in a different connection. Lenin deprived the thousands of Russians who had fled to the West after the civil war of their nationality. Statelessness prevented them from crossing borders. The Red Cross proposed using Nansen’s name on a special passport for refugees. The League of Nations approved the idea in 1922, at the same time appointing Nansen as its first High Commissioner for Refugees. The Nansen passport became very sought-after, and enabled such Russian artists as Igor Stravinsky, Sergey Rachmaninov, Marc Chagall and Anna Pavlova to begin new lives in the West.

A proof-print of the “Nansen Passport” published in France.

The nomination for the Nobel Peace Prize

It was thus hardly a surprise when Nansen was nominated for the Nobel Peace Prize the same autumn. The nominators included Professor Fredrik Stang,7 a member of the Nobel Committee, and the Danish group of the Inter-Parliamentary Union. They emphasised his work for the repatriation of prisoners-of-war, his efforts for the starving in Russia, and his ability to “appeal to world opinion with brotherly love as the driving and animating force”.

The adviser, Frede Castberg, who reported on Nansen’s candidacy, discussed the disagreement between Nansen and the Western governments about help to Russia. He defended Nansen’s position and concluded that Nansen had a strong influence on the work of the League of Nations because of “the high esteem in which Nansen’s personality is held, and the energy and wisdom with which he has stood up for his own proposals and that of his government in the Council of the League of Nations”.

In a private letter to a friend, Nansen wrote: “It is truly so strange to me and beyond my comprehension how all this business of the Peace Prize has come about; for it was really entirely by chance that I was driven to take up this work, which was not mine”. No doubt he was thinking among other things of Philip Noel-Baker’s initiative in persuading him to work for the League of Nations; he wrote to him concerning the Peace Prize that “If our work is worthy of it, you would have deserved it much more”.8

In the thorough biography of Nansen he published in 1996, Roland Huntford concluded that “Nansen is among the few really worthy winners of the Peace Prize, although he is probably the one who spent the shortest time earning it”.

Nansen spent the Peace Prize money in Russia, or the Soviet Union as the country was called from 1922 on. He had two model farms established for the development of new agricultural methods, one in the Ukraine and one by the Volga. Among the things they received were the first tractors in Soviet agriculture.

Nansen was made an honorary member of the Moscow Soviet, and many felt that he had become an uncritical “Russia worshipper”. In his book Russland og freden (Russia and Peace), he defended Lenin’s harsh methods and argued that they were necessary in order to build up the country.

“Ethnic separation” – a humanitarian solution?

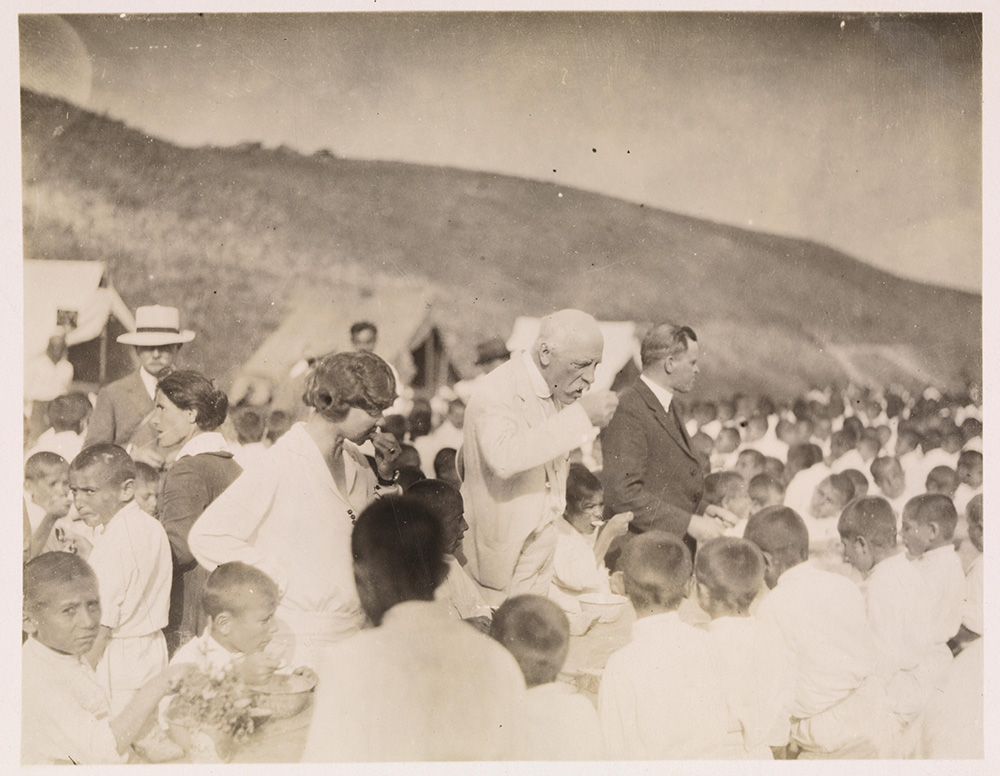

After the award, Nansen continued to devote all his energy to work for the League of Nations. The League asked him to resolve a complicated dispute which had arisen between Greece and Turkey. Turkey had been one of the losing parties in World War I, and the state was breaking up. Greece tried to profit from the situation by taking the west coast of Asia Minor, where a large proportion of the population was Greek. But Turkey’s new leader, Mustafa Kemal Ataturk,9 drove the Greeks out in 1922, in consequence of which over one million ethnic Greeks fled from Asia Minor to Greece. In the opposite direction, Turks fled from Greek-controlled territories.

Nansen decided that the only solution lay in “ethnic separation”. Turks and Greeks could not live together. He persuaded the Greek and Turkish governments to agree to a population exchange. Moslems in Greek areas would be exchanged with Greek-Orthodox groups in Asia Minor. The exchange was completed in 1924.

Nansen’s last years

The following year, influential circles tried to draw Nansen into Norwegian politics. Urged by the fear of Communism, Norwegian conservatives were looking for a strong leader.10 Although Nansen believed that Communism was necessary in a backward country like Russia, he was against Communism in the Norwegian context, because it ran counter to individualism. Nansen thought Communism was ridiculous in a developed country with universal suffrage. He shared with many others the ideas derived from social Darwinism that people needed to be led by their strongest and most skilful leaders. He was not a warm supporter of political parties or parliamentary democracy.

However, although Nansen lent his name to the efforts the conservatives were directing against Communism and Socialism in Norway, he refused to run for Prime Minister.