Carl von Ossietzky was born in Hamburg, though his father, a civil servant, had originally come from a village near the German-Polish border …

Carl von Ossietzky – Speed read

Carl von Ossietzky was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize for his uncompromising pacifism and defence of freedom of speech.

Full name: Carl von Ossietzky

Born: 3 October 1889, Hamburg, Germany

Died: 4 May 1938, Berlin, Germany

Date awarded: 24 November 1936

Concentration camp prisoner and peace prize laureate

In the autumn 1936, the Norwegian Nobel Committee made a daring decision, choosing for the first time to award the Nobel Peace Prize to a person at odds with his own country’s regime. Even before Adolf Hitler came to power in 1933, Carl von Ossietzky had been imprisoned for revealing how the German Government had built up a secret air force with the help of the Soviets, in direct violation of the peace treaty after WWI. Ossietzky was an uncompromising critic of political developments in Germany, and was one of the first persons to be interned in a concentration camp by the Nazis. Tortured and abused, he developed a serious heart condition and tuberculosis. The Norwegian Nobel Committee praised Ossietzky as a defender of freedom of speech and for serving as a symbol of peace. The prize helped to rouse public opinion in the struggle against Nazism.

”In times such as these we must hold the flag high. Cowardice is treacherous. The award to Ossietzky confirms that we are brave enough to show our colours. And we are met with respect. The Hitler regime has no respect for cowards, however; that has been amply brought to bear by Nazi policies.”

Wilhelm Keilhau, in a letter to the Chairman of the Norwegian Nobel Committee, Fredrik Stang, 3 December 1936.

The international campaign for Ossietzky

Ossietzky’s friends and colleagues worked to gain his release from captivity. In 1934, they decided to use the Nobel Peace Prize as a means of helping him, and over a two-year period the Norwegian Nobel Committee received over 500 letters nominating the controversial prisoner. The Norwegian Nobel Institute was also inundated by letters of support, particularly from the labour movement. Socialist Willy Brandt, who had fled from Nazi Germany to Norway, was an important supporter of Ossietzky. He campaigned for the persecuted prisoner and took contact with the Norwegian Nobel Committee. Brandt himself received the peace prize in 1971.

Nominations for Carl von Ossietzky

”I am, have always been and will always be a pacifist.”

Carl von Ossietzky, to Nazi leader Hermann Göring, autumn 1936.

| Pacifist From the Latin pacificus meaning peacemaking. A person who under no circumstance condones the use of violence; a peace advocate. Pacifists have been key figures in the international peace movement. |

Heated debate in Norway and abroad

In Norway, the right wing vehemently protested Ossietzky’s candidature. Conservatives such as Knut Hamsun maintained that the German prisoner was a criminal. Right-wing newspapers were unhappy with the Norwegian Nobel Committee’s decision, which they felt could provoke Germany. A number of Alfred Nobel’s family members criticised the decision, while renowned authors such as H.G. Wells and Aldous Huxley took Ossietzky’s side. Albert Einstein wrote to the Norwegian Nobel Committee, emphasising that awarding the peace prize to the German anti-Nazi would be of great historic significance.

”Ossietzky is not merely a symbol. He is something different and far more valuable. He is a mission and he is a man. These are the reasons why Ossietzky has been awarded his Peace Prize, these and no other.”

Chairman of the Nobel Committee Fredrik Stang, Presentation Speech, 10 December 1936.

Why was King Haakon VII absent from the award ceremony?

Breaking with established tradition, and without official explanation, the Norwegian royal family was not represented at the award ceremony for Ossietzky. Most likely, the Minister of Foreign Affairs, Halvdan Koht, had advised King Haakon against participating in order to make it clear that the Norwegian Government had played no role in the selection of Ossietzky. Minister Koht resigned from the Norwegian Nobel Committee in the autumn of 1936 to underscore the committee’s independence.

Hitler furious with the Norwegian Nobel Committee

Hitler denied Ossietzky permission to visit Oslo to receive the Nobel Peace Prize and proclaimed that no German could accept any Nobel Prize in the future. Nonetheless, the Nazis bowed to the mounting pressure of international criticism and allowed the laureate to receive medical treatment outside the concentration camp. But it was too late. The critically ill prisoner died in a Berlin hospital in May 1938.

Learn more

Disclaimer: Every effort has been made by the publisher to credit organisations and individuals with regard to the supply of photographs. Please notify the publishers regarding corrections.

Carl von Ossietzky – Photo gallery

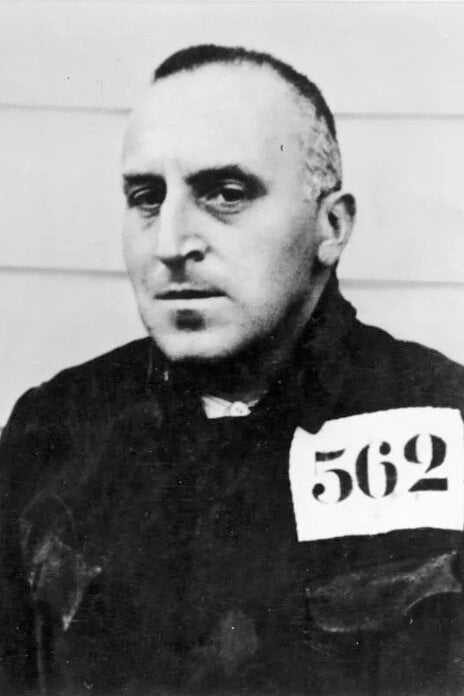

Prisoner Carl von Ossietzky at the Esterwegen concentration camp, 1934.

Bundesarchiv, Bild 183-93516-0010/Walter Sohst, Heiner Kurzbein/CC-BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

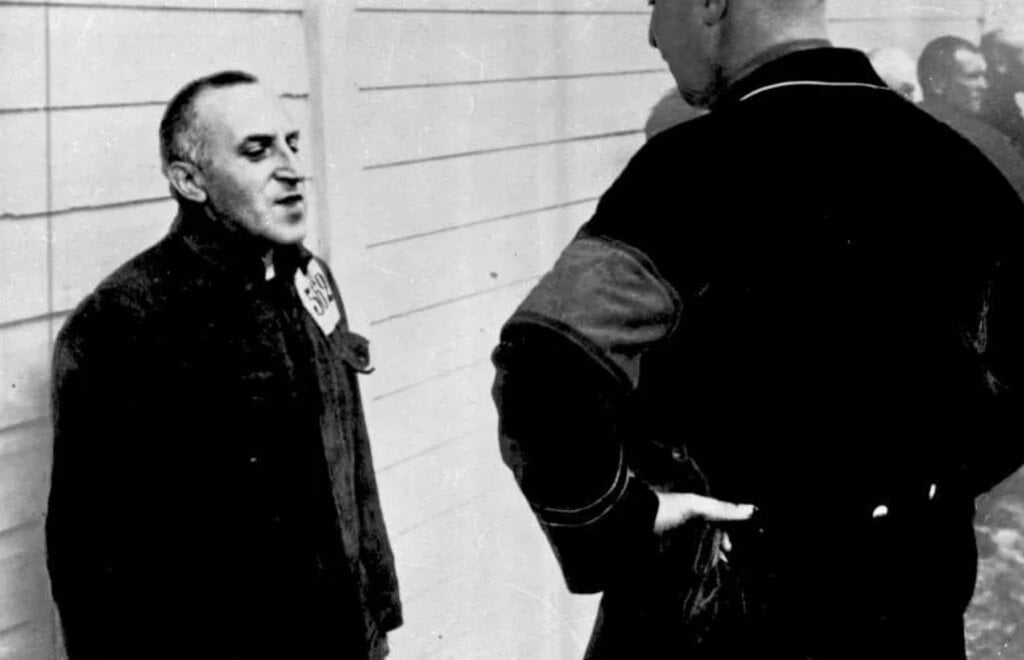

Carl von Ossietzky as a prisoner at the Esterwegen concentration camp, standing against a wall in front of a guard, 1934.

Bundesarchiv, Bild 183-R70579/CC-BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Carl von Ossietzky in front of the prison in Berlin-Tegel shortly before he began his prison sentence, May 1932. From left: Kurt Grossmann, Dr Rudolf Olden, both German League for Human Rights; Carl von Ossietzky, Dr Alfred Apfel, lawyer and Dr. Kurt Rosenfeld.

Bundesarchiv, Bild 183-B0527-0001-861/Unknown author/CC-BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Jane Addams nomination for Carl von Ossietzky. Jane Addams, awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 1931, was the first to nominate Carl von Ossietzky. The nomination arrived to the Norwegian Nobel Committee on 15 November 1934, and Carl von Ossietzky was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize the next year.

From the archives of the Norwegian Nobel Committee.

Carl von Ossietzky – Nominations

Award ceremony speech

Presentation Speech by Fredrik Stang*, Chairman of the Nobel Committee, on December 10, 1936

Carl von Ossietzky, who has been awarded the Peace Prize for 1935, belongs to no political party. He is not a Communist; he is not in any sense a conservative. Indeed, one cannot easily pin on him any of the usual political tags. If I were asked to give my impression of his personality, I should say that he seems to me to be a liberal or, if you prefer, a liberal of the old school. In using this description I do not have in mind economic liberalism, but liberalism in a completely different sense; a burning love for freedom of thought and expression; a firm belief in free competition in all spiritual fields; a broad international outlook; a respect for values created by other nations – and all of these dominated by the theme of peace.

An account of Ossietzky’s life is to be found in all the newspapers, and I shall not weary you by needless repetition.

He served in the war as an ordinary soldier. But the war had the effect of maturing and crystallizing the pacifist ideas which he had already cherished for a long time. When the war ended, he threw himself into work for peace. In Germany he was among those who formed the movement which took as its slogan: «No more war». He became secretary of the German Peace Society1, the president of which was Mr. Quidde, who was himself subsequently awarded the Nobel Peace Prize. Office work, however, failed to satisfy Ossietzky. He saw his true vocation as being in journalism. And so, leaving his job as secretary, he cast himself into the fray, applying his talents to the public platform as well as to newspapers and periodicals.

We are told that he is a gifted orator. The role in which he is best known, however, is that of journalist and essayist. He is an author of note; his style is supple, elegant, often bitingly witty. He covers a large field, writing about all aspects of modern politics, but his thought is focused above all on the cause of peace. His favorite weapon is the rapier. The sudden thrust, the lightning parry – these characterize his style. And in truth there is in him something of the knight, a quality which those who know him have remarked upon.

And yet we cannot today obtain a true impression of his merit and importance as a journalist simply by reading the articles he has written in the past. The work of the journalist is akin to that of the stage artist in that it lives in the present and cannot be re-created. The sum total of a journalist’s work does not reside in the faded print which you can, if you care to take the trouble, seek out and read. The sum total of the journalist’s craft, like that of the stage artist, lies in the impact it makes on the minds of others at the time. The truly great actor lives on in our minds, a vivid memory to the end of our days, a legend to be passed on to younger generations. It is somewhat the same with the journalist. We can browse through an old newspaper and read of events with which we were once well acquainted, and the words can still evoke some of that nervous tension, that vitality and warmth with which they were charged when cast into the maelstrom of the moment. But the spark of life is lost, for the words belong to their own day.

But balancing this we have the full force of the testimony of those who followed him in his fight and who were inspired by it. The sources of such testimony are so varied and their number so great that I cannot enumerate them here. Let me point to only one noteworthy fact: no less than six previous recipients of the Nobel Peace Prize have lent their support to Ossietzky’s candidacy for the award.

But, many people ask, has Ossietzky really contributed so much to peace? Has he not become a symbol of the struggle for peace rather than its champion?

In my opinion this is not so. But even if it were, how great is the significance of the symbol in our life! In religion, in politics, in public affairs, in peace and war, we rally round symbols. We understand the power they hold over us. Moreover, as a rallying point, a symbol may well be preferable to a personality. Men can all too often be compared to the «hulder», the wicked Norwegian fairy, beautiful when looked at from the front, but hollow in the back. Such is not the case with the symbol because the symbol is born of an idea and is the bearer of an idea. It exists through the idea which first created it and reflects it faithfully and without distortion.

We have among our poems a few lines about a symbol, lines which are quoted more and more frequently:

For that is the great thing and the sublime thing,

that the banner may wave, though the man has to die.

The symbol certainly has its value. But Ossietzky is not just a symbol. He is something quite different and something much more. He is a deed; and he is a man.

It is on these grounds that Ossietzky has been awarded the Nobel Peace Prize, and on these grounds alone. His candidacy was examined in the same manner as that of all others, and the decision was reached according to the same principles. If we look back upon all the men and women who have received the Peace Prize over the years, we find that they are of widely divergent personalities and views and that the lives of many of them were marked by passion, grief, and struggle. It is quite obvious that the Nobel Committee, in awarding the prize to these different personalities, has neither shared all the opinions which they held nor declared its solidarity with all of their work. The wish of the Nobel Committee has always been to fulfill its task and its obligation, namely, to reward work for peace – that and nothing else. And the Nobel Committee has been able to do so because it is totally independent. It is not answerable to anyone, nor do its decisions commit anyone other than itself.

In awarding this year’s Nobel Peace Prize to Carl von Ossietzky we are therefore recognizing his valuable contribution to the cause of peace – nothing more, and certainly nothing less.

* Mr. Stang delivered this speech in the Norwegian Nobel Institute on December 10, 1936. Because of ill health and the «protective custody» under which he was held (see biography), the laureate was unable to be present to accept his prize – the Peace Prize for 1935 which was reserved in that year – or to give a Nobel lecture. The Ossietzky candidacy brought about a change in the practice governing membership on the Nobel Committee. Since the award of the prize to Ossietzky would be interpreted as implying disapproval of the Nazi government, Halvdan Koht, one of the members of the Committee and Norwegian foreign minister at that time, decided to withdraw from the deliberations of the Committee, a decision made also by Johan L. Mowinckel who had held office as prime minister and as foreign minister. Their places were filled by substitutes. In 1937 the Parliament resolved «that members of the Nobel Committee, upon becoming appointed to the Government, shall withdraw from the Committee» (August Schou, «The Peace Prize» in Nobel: The Man and His Prizes, p. 606). The translation of Mr. Stang’s speech is based on the Norwegian text in Les Prix Nobel en 1936, which also carries a French translation.

1. Deutsche Friedensgesellschaft, founded 1892.

The Nobel Peace Prize 1935

Carl von Ossietzky – Biographical

Carl von Ossietzky (October 3, 1889-May 4, 1938) was born in Hamburg, though his father, a civil servant, had originally come from a village near the German-Polish border. Seven years after Ossietzky’s father died in 1891, his mother married Gustav Walther, a Social Democrat, who was influential in shaping Ossietzky’s later political attitudes.

Ossietzky’s academic achievement being uneven, he left school at the age of seventeen to become an administrative civil servant in his native city. He soon turned to journalism, the profession in which he was to make a career, his first work appearing in Das Freie Volk [The Free People], the weekly organ of the Demokratische Vereinigung [Democratic Union]. On July 5, 1913, an article by Ossietzky criticizing a pro-military court decision in Erfurt drew charges of «insult to the common good» from the Prussian War Ministry. When Ossietzky was called to make a court appearance some time after his marriage on May 22, 1914, to the Englishwoman Maud Woods, his young wife secretly made arrangements to pay his fine.

Though Ossietzky’s health was poor, he was called up for military service in June, 1916, with the Bavarian Pioneer Regiment. After the war, Ossietzky, now a confirmed pacifist as well as democrat, returned to Hamburg where he stirred public opinion by speeches on his doctrine of educating people to a «peace mentality», became president of the local chapter of the German Peace Society, and founded Der Wegweiser [The Signpost], an enterprise which soon failed because of lack of financial backing.

Ossietzky then accepted an appointment as secretary of the German Peace Society, with headquarters in Berlin. There he created the monthly Mitteilungsblatt [Information Sheet], which appeared first on January 1, 1920, and became a regular contributor to Monisten Monatsheften [Monists’ Monthly], using the pseudonym «Thomas Murner»1. A man of intense temperament, Ossietzky soon tired of the office work of the German Peace Society and accepted the post of foreign editor on the staff of the Berliner Volkszeitung [Berlin People’s Paper], a paper whose editorial policy was nonpartisan, democratic, and antiwar.

Ossietzky had a brief flirtation with politics in 1923-1924 when the entire editorial staff of the Berliner Volkszeitung became involved in the founding of a new party, the Republican Party. After the defeat which the party suffered in the Reichstag election of May, 1924, Ossietzky joined the political weekly Tagebuch [Journal], revealing in his contributions to that periodical a disillusionment with his own political efforts and some skepticism about the wisdom of the masses2.

In 1926 Siegfried Jacobsohn, founder and editor of Die Weltbühne [The World Stage], offered Ossietzky a position on his editorial staff. Jacobsohn had already become involved in efforts to uncover and publicize the secret rearmament of Germany, and Carl von Ossietzky was to continue this unpopular editorial policy, for Jacobsohn died unexpectedly in December, 1926, and shortly thereafter his widow named Ossietzky editor-in-chief. In March, 1927, Die Weltbühne published an article by Berthold Jacob3 which criticized the Reichswehr for condoning paramilitary organizations. Ossietzky, as the editor responsible, was tried for libel, found guilty, and sentenced to one month in prison.

Refusing to be intimidated, he published in March, 1929, an article by Walter Kreiser which was, in effect, part of a campaign by Ossietzky of opposition to secret German rearmament in violation of the Treaty of Versailles. At a hearing in August, 1929, Ossietzky was charged with betrayal of military secrets, was tried in November, 1931, found guilty, sentenced to eighteen months in Spandau Prison, and released after seven months in the Christmas amnesty of 1932.

By early 1933, Ossietzky, more clear-sighted than his optimistic colleagues’ recognized the gravity of the political situation in Germany, but he refused to leave the country, saying that a man speaks with a hollow voice from across the border. On February 28, 1933, the morning after the Reichstag fire, Ossietzky was apprehended at home by the secret police, sent to a Berlin prison, then to concentration camps, first at Sonnenburg and later at Esterwegen-Papenburg. In these camps, according to reports from fellow prisoners, he was mistreated, even forced to perform heavy labor although he had already sustained a heart attack.

Ossietzky’s candidacy for the Peace Prize was first suggested in 1934. Berthold Jacob, a companion in many a cause, may have been the first to formulate an actual plan to secure the nomination. The idea was taken up by his colleagues in the German League for Human Rights4, by Hellmut von Gerlach, a former associate on Die Weltbühne who undertook a letterwriting campaign from Paris, by organizations and famous people in many parts of the world. The nomination for 1934 arrived too late; the prize for 1935 was reserved in that year but in 1936 was voted to Ossietzky.

At this point, Ossietzky, ill with tuberculosis, had little time left to live, but the government refused to release him from the concentration camp and demanded that he decline the Nobel Prize, a demand that Ossietzky did not honor. The German Propaganda Ministry declared publicly that Ossietzky was free to go to Norway to accept the prize, but secret police documents indicate that Ossietzky was refused a passport, and, although allowed to enter a civilian hospital, was kept under constant surveillance until his death in May, 1938.

The German press was forbidden to comment on the granting of the prize to Ossietzky, and the German government decreed that in the future no German could accept any Nobel Prize.

Ossietzky’s last public appearance was at a short court hearing at which his lawyer was sentenced to two years at hard labor for embezzling most of Ossietzky’s prize money.

| Selected Bibliography |

| Frei, Bruno, Carl v. Ossietzky: Ritter ohne Furcht und Tadel. Berlin, Aufbau, 1966. |

| Greuner, Ruth and Reinhart, Ich stehe links: Carl von Ossietzky über Geist und Ungeist der Weimarer Republik. Berlin, Buchverlag der Morgen, 1963. |

| Grossmann, Kurt R., Ossietzky: Ein deutscher Patriot. Munich, Kindler, 1963. Has an extensive bibliography of Ossietzky’s articles compiled by Rudolf Radler, pp. 553-570. |

| Hartmann, Heinz Ernst Otto, Carl von Ossietzky. Fürstenfeldbruck 2/Bayern, Steinklopfer, 1960. |

| Jacob, Berthold, Warum schweigt die Welt? Paris, Éditions du Phénix, 1936. |

| Koplin, Raimund, Carl von Ossietzky als politischer Publizist. Berlin, Leber, 1964. Contains bibliography of secondary materials on Ossietzky, pp. 235-240. |

| Ossietsky, Carl von, Schriften. I & II. Berlin, Aufbau, 1966. |

| Ossietzky, Maud von, Maud v. Ossietzky erzählt: Ein Lebensbild. Berlin, Buchverlag der Morgen, 1966. |

| Rieber-Mohn, Hallvard, Det blodige nei: Tyske skjetber fra Weimar til Bonn. Oslo Aschehoug, 1967. With a bibliographical note. |

| What Was His Crime?: The Case of Carl von Ossietzky. London, Camelot Press, 1937. |

1. Thomas Murner (1475-1537), German priest, satirist, and opponent of the Reformation. Ossietzky turned to the pseudonym again in 1932, when he published articles while in prison.

2. Kurt Grossmann, Ossietzky, pp. 106-107.

3. Berthold Jacob, «Plaidoyer für Schulz» in Die Weltbühne (March, 1927).

4. Founded during WWI with the name Bund Neues Vaterland [League of the New Fatherland] and renamed in 1922 after a similar French organization to underscore efforts to bring about German-French understanding; Ossietzky served for a time on the administrative council.

This autobiography/biography was written at the time of the award and first published in the book series Les Prix Nobel. It was later edited and republished in Nobel Lectures. To cite this document, always state the source as shown above.

The Nobel Foundation's copyright has expired.